Validating New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): A 2025 Roadmap for Scientific Confidence and Regulatory Acceptance

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) for regulatory decision-making.

Validating New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): A 2025 Roadmap for Scientific Confidence and Regulatory Acceptance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) for regulatory decision-making. It explores the scientific foundations, key technologies like organ-on-chip and AI, and the evolving regulatory landscape, including the FDA's 2025 roadmap. The content addresses major validation hurdles, such as data quality and model interpretability, and presents emerging solutions like tiered validation frameworks and public-private partnerships. By synthesizing current best practices and future directions, this resource aims to accelerate the confident adoption of these human-relevant tools in modern toxicology and safety assessment.

The 'Why' Behind NAMs: Building a Scientifically and Regulatorily Sound Foundation

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) represent a transformative shift in toxicology and chemical safety assessment, moving beyond the simple goal of replacing animal testing to establishing a new, human-relevant paradigm for predicting adverse health effects. The term, formally coined in 2016, encompasses a broad suite of innovative tools and integrated approaches that provide more predictive, mechanistically-informed systems for human health risk assessment [1]. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), NAMs are defined as "...a broadly descriptive reference to any technology, methodology, approach, or combination thereof that can be used to provide information on chemical hazard and risk assessment that avoids the use of intact animals..." [2]. This definition underscores a crucial distinction: NAMs are not merely any new scientific method but are specifically fit-for-purpose tools developed for regulatory hazard and safety assessment of chemicals, drugs, and other substances [1].

The fundamental premise of NAMs-based Next Generation Risk Assessment (NGRA) is that safety assessments should be protective for humans exposed to chemicals, utilizing an exposure-led, hypothesis-driven approach that integrates in silico, in chemico, and in vitro approaches [3]. This represents a significant departure from traditional animal-based systems, which, despite their historical reliability, face numerous challenges including capacity issues for testing thousands of new substances, species specificity limitations, and ethical concerns [2]. The vision for NAMs does not aim to replace animal toxicity tests on a one-to-one basis but to approach toxicological safety assessment through consideration of exposure and mechanistic information using a range of human-relevant models [3].

Comparative Analysis: NAMs vs. Traditional Animal Models

Fundamental Differences in Approach and Predictive Value

The transition from traditional animal models to NAMs represents more than a simple methodological shift—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how safety assessment is conceptualized and implemented. Traditional risk assessment methodologies have historically relied upon animal testing, despite growing concerns regarding interspecies inconsistencies, reproducibility challenges, substantial cost burdens, and ethical considerations [2]. While rodent models have served as the established "gold standard" for decades, their true positive human toxicity predictivity rate remains only 40%–65%, highlighting significant limitations in their translational relevance for human safety assessment [3].

NAMs address these limitations by focusing on human-relevant biology and mechanistic information rather than merely assessing organ pathology as observed in animals [2]. This human-focused approach provides a fundamentally different way to assess human hazard and risk, moving beyond the tradition of assessing toxicity in whole animals as the primary basis for human safety decisions [3]. The comparative advantages of each approach are detailed in the table below:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional Animal Models vs. NAMs

| Aspect | Traditional Animal Models | New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Relevance | Limited human relevance due to species differences; rodents have 40-65% human toxicity predictivity [3] | Human-relevant systems using human cells, tissues, and computational models [3] [1] |

| Mechanistic Insight | Primarily observes organ pathology without detailed molecular mechanisms [2] | Provides deep mechanistic information through multi-level omics and pathway analysis [2] [1] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established with historical acceptance; required by many regulations [2] [3] | Growing but limited acceptance; increasing regulatory support with FDA Modernization Act 2.0 [4] |

| Testing Capacity | Low-throughput with capacity issues for thousands of chemicals [2] | High-throughput screening capable of testing thousands of compounds [1] |

| Ethical Considerations | Raises significant animal welfare concerns and follows 3Rs principles [3] [1] | Ethically preferable with reduced animal use; aligns with 3Rs principles [3] [1] |

| Cost & Time Efficiency | High costs and lengthy timelines (years for comprehensive assessment) [2] | Reduced costs and shorter timelines; AI predicted toxicity of 4,700 chemicals in 1 hour [4] |

| Complexity of Endpoints | Can assess complex whole-organism responses but limited for less accessible endpoints [2] | Better for specific mechanisms but challenges in capturing complex systemic toxicity [3] |

Performance Comparison for Specific Toxicity Endpoints

Substantial research has quantitatively compared the performance of NAMs against traditional animal models for specific toxicity endpoints. A compelling example comes from a 2024 comparative case study on hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic pesticide active substances, where substances were tested in human HepaRG hepatocyte cells and RPTEC/tERT1 renal proximal tubular epithelial cells at non-cytotoxic concentrations and analyzed for effects on the transcriptome and parts of the proteome [2]. The study revealed that transcriptomics data, analyzed using three bioinformatics tools, correctly predicted up to 50% of in vivo effects, with targeted protein analysis revealing various affected pathways but generally fewer effects present in RPTEC/tERT1 cells [2]. The strongest transcriptional impact was observed for Chlorotoluron in HepaRG cells, which showed increased CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 expression [2].

For more defined toxicity endpoints, NAMs have demonstrated remarkable success. Defined Approaches (DAs)—specific combinations of data sources with fixed data interpretation procedures—have been formally adopted in OECD test guidelines for serious eye damage/eye irritation (OECD TG 467) and skin sensitization (OECD TG 497) [3]. For skin sensitization, a combination of three human-based in vitro approaches demonstrated similar performance to the traditionally used Local Lymph Node Assay (LLNA) performed in mice, with the combination of approaches actually outperforming the LLNA in terms of specificity [3]. Another case study involving crop protection products Captan and Folpet, which employed a multiple NAM testing strategy of 18 in vitro studies, appropriately identified these substances as contact irritants, demonstrating that a suitable risk assessment could be performed with available NAM tests that aligned with risk assessments conducted using existing mammalian test data [3].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of NAMs for Specific Applications

| Application/Endpoint | NAM Approach | Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatotoxicity Prediction | Transcriptomics in HepaRG cells | Correctly predicted up to 50% of in vivo effects | [2] |

| Skin Sensitization | Defined Approaches (DAs) combining in vitro methods | Outperformed LLNA in specificity; equivalent or superior to animal tests | [3] |

| Toxicity Screening | AI prediction of food chemicals | 87% accuracy for 4,700 chemicals in 1 hour (vs. 38,000 animals) | [4] |

| Steatosis Identification | AOP-based in vitro toolbox in HepaRG cells | Established transcript and protein marker patterns for steatotic compounds | [2] |

| Complex Toxicity Assessment | Multiple NAM testing strategy (18 in vitro studies) | Appropriately identified contact irritants in line with mammalian data | [3] |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols in NAMs

Major Categories of NAMs and Their Applications

NAMs encompass a diverse suite of tools and technologies that can be used either alone or in combination to evaluate chemical and drug safety without relying on animal testing [1]. These methodologies include:

In Vitro Models: These systems use cultured cells or tissues to assess biological responses and range from simple 2D cell cultures to more physiologically relevant 3D spheroids, organoids, and sophisticated Organ-on-a-Chip models [1]. The latter are microengineered systems that mimic organ-level functions, enabling dynamic studies of toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and mechanisms of action [1]. For hepatotoxicity studies, HepaRG cells have emerged as one of the best currently available options—after differentiation, they develop CYP-dependent activities close to the levels in primary human hepatocytes and feature the capability to induce or inhibit a variety of CYP enzymes, plus expression of phase II enzymes, membrane transporters and transcription factors [2].

In Silico Models: Computational approaches simulate biological responses or predict chemical properties based on existing data [1]. These include Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSARs) that predict a chemical's activity based on its structure; Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models that simulate how chemicals are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted in the body; and Machine Learning/AI approaches that leverage big data to uncover novel patterns and make toxicity predictions [1] [4]. These tools can screen thousands of compounds in silico before any lab testing is conducted, helping prioritize candidates and reduce unnecessary experimentation [1].

Omics-Based Approaches: These technologies analyze large datasets from genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics to identify molecular signatures of toxicity or disease [1]. They offer mechanistic insights into how chemicals affect biological systems, enable biomarker discovery for early indicators of adverse effects, and facilitate pathway-based analyses aligned with Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs) [1]. These methods support a shift toward mechanistic toxicology, focusing on early molecular events rather than late-stage pathology [1].

In Chemico Methods: These techniques assess chemical reactivity without involving biological systems [1]. A common application is testing for skin sensitization, where the ability of a compound to bind to proteins is evaluated directly through assays like the Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay (DPRA) [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key NAMs Applications

Transcriptomics for Hepatotoxicity Assessment

Objective: To predict chemical-induced hepatotoxicity using human-relevant in vitro models and transcriptomic analysis.

Cell Model: Differentiated HepaRG cells, which undergo a differentiation process resulting in CYP-dependent activities close to the levels in primary human hepatocytes [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Culture and Differentiation: Maintain HepaRG cells according to established protocols, allowing for complete differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells, typically requiring 2-4 weeks [2].

- Compound Exposure: Treat cells with test substances at non-cytotoxic concentrations, determined through preliminary viability assays. Include appropriate vehicle controls and positive controls [2].

- RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Harvest cells after specified exposure periods (e.g., 24h, 48h) and extract total RNA using standardized methods. Assess RNA quality and integrity [2].

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Conduct gene expression profiling using quantitative real-time PCR arrays or comprehensive RNA sequencing. Analyze differential gene expression compared to vehicle controls [2].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process transcriptomics data using multiple bioinformatics tools for pathway analysis, gene set enrichment, and network modeling. Connect in vitro endpoints to in vivo observations where possible [2].

- Targeted Protein Analysis: Validate key findings at the protein level using multiplexed microsphere-based sandwich immunoassays or Western blotting for proteins of interest [2].

Key Parameters Measured: Differential gene expression, pathway enrichment, protein level changes, correlation with established in vivo effects [2].

Defined Approaches for Skin Sensitization

Objective: To identify skin sensitizers without animal testing using a combination of in chemico and in vitro assays within a Defined Approach.

Experimental Protocol:

- Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay (DPRA): Incubate test chemicals with synthetic peptides containing either cysteine or lysine. Measure peptide depletion via high-performance liquid chromatography after 24 hours to assess covalent binding potential [1].

- KeratinoSens Assay: Use a transgenic keratinocyte cell line containing a luciferase gene under the control of the antioxidant response element (ARE). Measure luciferase induction after 48-hour exposure to identify activation of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway [1].

- Human Cell Line Activation Test (h-CLAT): Expose THP-1 or U937 cells (human monocytic leukemia cell lines) to test substances for 24 hours. Measure cell surface expression of CD86 and CD54 via flow cytometry to assess dendritic cell-like activation [1].

- Data Integration Procedure: Apply a fixed data interpretation procedure, as outlined in OECD TG 497, to integrate results from the individual assays into a single prediction of skin sensitization potential [3].

Key Parameters Measured: Peptide reactivity, ARE activation, CD86 and CD54 expression, integrated prediction model [3] [1].

Integrated Testing Strategies and Visualization

The Power of Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA)

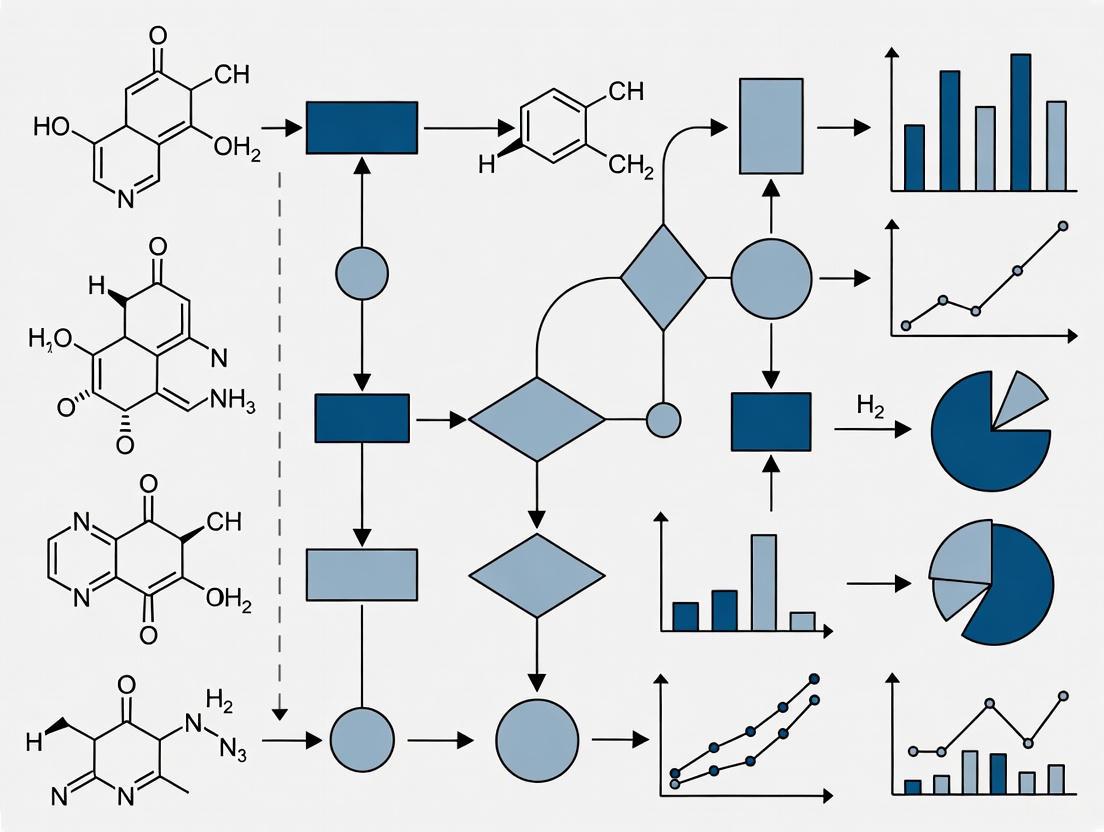

One of the most significant strengths of NAMs lies in their ability to complement each other through Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA) [1]. By combining in vitro, in silico, and omics data within these integrated frameworks, researchers can build a weight-of-evidence to support safety decisions that exceeds the predictive value of any single method [1]. A representative workflow demonstrates how different NAMs can be integrated to assess chemical safety:

This integrated approach allows for a comprehensive assessment where computational models might initially predict a compound's potential hepatotoxicity, followed by experimental validation using Organ-on-a-Chip liver models to test effects on human liver tissue under physiologically relevant conditions [1]. Subsequent transcriptomic profiling can reveal specific pathways perturbed by the exposure, and all this information can be fed into an Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework to map out the progression from molecular interaction to adverse outcome [1]. This synergy not only improves confidence in NAM-derived data but also aligns with regulatory goals to reduce reliance on animal testing while ensuring human safety [1].

Adverse Outcome Pathway Framework in NAMs

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework represents a critical conceptual foundation for organizing mechanistic knowledge in toxicology and forms the basis for many integrated testing strategies [2]. An AOP describes a sequential chain of causally linked events at different levels of biological organization that leads to an adverse health effect in humans or wildlife [2]. The following diagram illustrates a generalized AOP framework and how different NAMs interrogate specific key events within this pathway:

A practical example of AOP implementation is the in vitro toolbox for steatosis developed based on the AOP concept by Vinken (2015) and implemented by Luckert et al. (2018) [2]. This approach employed five assays covering relevant key events from the AOP in HepaRG cells after incubation with the test substance Cyproconazole, concurrently establishing transcript and protein marker patterns for identifying steatotic compounds [2]. These findings were subsequently synthesized into a proposed protocol for AOP-based analysis of liver steatosis in vitro [2].

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for NAMs Implementation

Successful implementation of NAMs requires specific research reagents, cell models, and technological platforms that enable human-relevant safety assessment. The table below details key solutions essential for conducting NAMs-based research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NAMs Implementation

| Reagent/Platform | Type | Key Applications | Function in NAMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| HepaRG Cells | In Vitro Cell Model | Hepatotoxicity assessment, steatosis studies, metabolism studies [2] | Differentiates into hepatocyte-like cells with CYP activities near primary human hepatocytes; expresses phase I/II enzymes and transporters [2] |

| RPTEC/tERT1 Cells | In Vitro Cell Model | Nephrotoxicity assessment, renal transport studies [2] | Immortalized renal proximal tubular epithelial cell line; model for kidney toxicity [2] |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Platforms | Microphysiological System | Multi-organ toxicity, ADME studies, disease modeling [1] [4] | Microengineered systems mimicking organ-level functions with tissue-tissue interfaces and fluid flow [1] |

| Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay (DPRA) | In Chemico Assay | Skin sensitization assessment [1] | Measures covalent binding potential of chemicals to synthetic peptides; part of skin sensitization DAs [1] |

| h-CLAT (Human Cell Line Activation Test) | In Vitro Assay | Skin sensitization potency assessment [1] | Measures CD86 and CD54 expression in THP-1/U937 cells; part of skin sensitization DAs [1] |

| Transcriptomics Platforms | Omics Technology | Mechanistic toxicology, biomarker discovery, AOP development [2] [1] | Identifies gene expression changes; correctly predicted up to 50% of in vivo effects in case study [2] |

| PBPK Modeling Software | In Silico Tool | Pharmacokinetic prediction, exposure assessment, extrapolation [1] | Models absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion; enables in vitro to in vivo extrapolation [1] |

New Approach Methodologies represent more than a mere replacement for animal testing—they embody a fundamental transformation in how we understand and assess the safety and efficacy of chemicals and pharmaceuticals [1]. By integrating in vitro models, computational tools, and omics-based insights, NAMs offer a pathway to faster, more predictive, and human-relevant science that addresses both ethical concerns and scientific limitations of traditional approaches [1]. The growing regulatory support, exemplified by the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, European regulatory agencies' increasing incorporation of NAMs into risk assessment frameworks, and OECD guidelines for validated NAMs, indicates a shifting landscape toward broader acceptance [1] [4].

However, challenges remain in the widespread adoption of NAMs for regulatory safety assessment. These include the need for continued validation and confidence-building among stakeholders, addressing scientific and technical barriers, and adapting regulatory frameworks that have historically relied on animal data [3]. The recently proposed framework from ICCVAM (Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods) offers a promising adaptive approach based on the key concept that the extent of validation for a specific NAM depends on its Context of Use (CoU) [4]. This framework moves away from 'one-test-fits-all' applications and allows flexibility based on the question being asked and the level of confidence needed for decision-making [4].

As regulatory frameworks evolve and validation efforts expand, NAMs will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in toxicology, risk assessment, and drug development [1]. For researchers, industry leaders, and regulators, the time to invest in and adopt NAMs is now, with the recognition that these approaches offer not just an alternative to animal testing, but a superior paradigm for human-relevant safety assessment that benefits both public health and scientific progress.

The pharmaceutical industry faces a persistent productivity crisis, characterized by a 90% failure rate for investigational drugs entering clinical trials [5]. This staggering rate of attrition represents one of the most significant challenges in modern medicine, with failed Phase III trials alone costing sponsors between $800 million and $1.4 billion each [5]. While multiple factors contribute to this problem, a predominant reason is generally held to be the failure of preclinical animal models to predict clinical efficacy and safety in humans [6].

The fundamental issue lies in what scientists call the "translation gap" – the inability of findings from animal studies to reliably predict human outcomes. Analysis of systematic reviews reveals that animal studies show approximately 50% concordance with human studies, essentially equivalent to random chance [5]. This translates to roughly 20% of overall clinical trial failures being directly attributable to issues with translating animal models to human patients [5]. In certain fields, such as vaccination development against AIDS, prediction failure of chimpanzee and macaque models reaches 100% [7].

This comparison guide examines the scientific limitations of traditional animal models and evaluates emerging New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that offer more human-relevant pathways for drug discovery and development. By objectively comparing these approaches, we aim to provide researchers with the evidence needed to advance more predictive and efficient drug development strategies.

Quantitative Analysis of Clinical Failure Rates

Understanding the precise contribution of animal model limitations to clinical trial failures requires examining failure statistics across development phases. The table below summarizes the success rates and primary failure factors throughout the drug development pipeline.

Table 1: Clinical Trial Success Rates and Failure Factors by Phase

| Development Phase | Success Rate | Primary Failure Factors | Contribution of Animal Model Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I to Phase II | 52% [5] | Safety, pharmacokinetics | ~20% of overall failures [5] |

| Phase II to Phase III | 28.9% [5] | Efficacy, dose selection | Poor translation evident in neurological diseases (85% failure) [5] |

| Phase III to Approval | 57.8% [5] | Efficacy in larger populations | Species differences undermine predictability [6] |

| Overall Approval Rate | 6.7% [5] | Mixed efficacy/safety issues | 20% of failures directly attributable [5] |

When these failure factors are analyzed comprehensively, pure clinical trial design issues emerge as the most significant contributor at 35% of failures, followed by recruitment and operational issues at 25%, while animal model translation limitations account for 20%, and intrinsic drug safety/efficacy issues account for the remaining 20% [5]. This suggests that approximately 60% of clinical trial failures are potentially preventable through improved methodology and planning, compared to only 20% attributable to limitations in animal models [5].

Fundamental Limitations of Animal Models

Scientific and Physiological Barriers

The external validity of animal models – the extent to which research findings in one species can be reliably applied to another – is undermined by several fundamental scientific limitations:

Species Differences in Disease Mechanisms: For many diseases, underlying mechanisms are unknown, making it difficult to develop representative animal models [7]. Animal models are often designed according to observed disease symptoms or show disease phenotypes that differ crucially from human ones when underlying mechanisms are reproduced genetically [7]. A prominent example is the genetic modification of mice to develop human cystic fibrosis in the early 1990s; unexpectedly, the mice showed different symptoms from human patients [7].

Unrepresentative Animal Samples: Laboratory animals tend to be young and healthy, whereas many human diseases manifest in older age with comorbidities [6]. For instance, animal studies of osteoarthritis tend to use young animals of normal weight, whereas clinical trials focus mainly on older people with obesity [6]. Similarly, animals used in stroke studies have typically been young, whereas human stroke is largely a disease of the elderly [6].

Inability to Mimic Human Complexity: Most human diseases evolve over time as part of the human life course and involve complexity of comorbidity and polypharmacy that animal models cannot replicate [6]. While it may be possible to grow a breast tumour on a mouse model, this does not represent the human experience because most human breast cancer occurs post-menopausally [6].

Methodological Flaws in Preclinical Animal Research

Beyond physiological differences, methodological issues further limit the predictive value of animal studies:

Underpowered Studies: Systematic reviewing of preclinical stroke data has shown that considerations like sample size calculation in the planning phase of a study are hardly ever performed [7]. Many animal studies are underpowered, making it impossible to reliably detect group differences with high enough probability [7].

Standardization Fallacy: Overly strict standardization of environmental parameters may lead to spurious results with no external validity [7]. This "standardization fallacy" was demonstrated in studies where researchers found large effects of testing site on mouse behavior despite maximal standardization efforts [7].

Poor Study Design: Animal studies often lack aspects of study design fully established in clinical trials, such as randomization of test subjects to treatment or control groups, and blinded performance of treatment and blinded assessment of outcome [7]. Such design aspects seem to lead to overestimated drug efficacy in preclinical animal research if neglected [7].

Table 2: Methodological Limitations in Animal Research and Their Impact

| Methodological Issue | Impact on Data Quality | Effect on Clinical Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Underpowered studies | Small group sizes; inability to detect true effects | False positives/negatives; unreliable predictions |

| Lack of blinding | Overestimation of intervention effects by ~13% [6] | Inflated efficacy expectations in clinical trials |

| Unrepresentative models | Homogeneous samples not reflecting human diversity | Limited applicability to heterogeneous human populations |

| Poor dose optimization | Inadequate Phase II dose-finding | 25% of design-related failures in clinical trials [5] |

Defining NAMs and Their Applications

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) refer to innovative technologies and approaches that can provide human-relevant data for chemical safety and efficacy assessments. These include:

- In vitro systems: Cell-based assays, 3D tissue models, organoids, and organ-on-chip devices

- In silico approaches: Computational models, AI-driven predictive platforms, and virtual screening

- Omics technologies: Genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiling

- Stem cell technologies: Human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived models

The validation and qualification of NAMs have gained significant regulatory and industry support. In June 2025, the American Chemistry Council's Long-Range Research Initiative (LRI) joined the NIH Common Fund's Complement Animal Research In Experimentation (Complement-ARIE) public-private partnership to accelerate the scientific development and evaluation of NAMs [8]. This collaboration aims to enhance the robustness and transparency of NAMs and the availability of non-animal methods for modernizing regulatory decision-making [8].

Regulatory Shift Toward NAMs

Recent regulatory developments signal a significant shift toward acceptance of NAMs:

- FDA Modernization Act 2.0: Allows for alternative testing methods in the drug approval process, reflecting growing recognition of animal model limitations [5].

- U.S. FDA Advances in Non-Animal Testing (April 2025): The FDA released a formal roadmap to reduce animal testing in preclinical safety studies, encouraging New Approach Methodologies such as Organ-on-Chip, Computational Models, and advanced In-Vitro assays [9].

- Increased Industry Adoption: Most of the world's leading pharmaceutical companies now rely on emerging human-based technologies like Vivodyne's automated robotic platforms due to the recognition that animal models are poor predictors of human biology [10].

Comparative Analysis: Animal Models vs. Emerging NAMs

Direct Comparison of Key Parameters

Table 3: Animal Models vs. Human-Based NAMs - Comparative Performance Metrics

| Parameter | Traditional Animal Models | Emerging NAMs | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy for Human Response | ~50% concordance [5] | 85%+ claimed by leading platforms [10] | NAMs by ~35% |

| Throughput | Weeks to months per study | 10,000+ human-tissue experiments per robotic run [10] | NAMs by orders of magnitude |

| Cost per Data Point | High (housing, care, monitoring) | Declining with automation | NAMs increasingly favorable |

| Species Relevance | Significant differences in physiology, metabolism, disease presentation | Human cells and tissues | NAMs eliminate cross-species uncertainty |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Established but evolving | Growing rapidly with recent FDA roadmap [9] | Animal models currently, but gap closing |

| Data Richness | Limited by practical constraints | Multi-omic data (transcriptomics, proteomics, imaging) [10] | NAMs enable deeper mechanistic insights |

Specific Technology Comparisons

High-Throughput Screening Platforms

The global high throughput screening market is estimated to be valued at USD 26.12 Billion in 2025 and is expected to reach USD 53.21 Billion by 2032, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate of 10.7% [9]. This growth reflects increasing adoption across pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and chemical industries, driven by the need for faster drug discovery and development processes.

- Cell-Based Assays: This segment is projected to account for 33.4% of the market share in 2025, underscoring their growing importance as they more accurately replicate complex biological systems compared to traditional biochemical methods [9].

- Instruments Segment: Liquid handling systems, detectors, and readers are projected to account for 49.3% share in 2025, driven by steady improvements in speed, precision, and reliability of assay performance [9].

Organ-on-Chip and Complex Tissue Models

Companies like Vivodyne are developing automated robotic platforms that grow and analyze thousands of fully functional human tissues, providing unprecedented, clinically relevant human data at massive scale [10]. These systems can grow over 20 distinct human tissue types, including bone marrow, lymph nodes, liver, lung, and placenta, and model diseases such as cancer, fibrosis, autoimmunity, and infections [10].

Experimental Protocols for Key NAMs

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening Using Cell-Based Assays

Purpose: To rapidly identify hit compounds that modulate specific biological targets using human-relevant systems.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell lines (primary human cells or iPSC-derived cells)

- Compound libraries

- Assay kits (e.g., INDIGO Biosciences' Melanocortin Receptor Reporter Assay family [9])

- Liquid handling systems (e.g., Beckman Coulter's Cydem VT System [9])

- Detection and reading instruments

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture human-derived cells in 384-well or 1536-well plates using automated liquid handling systems.

- Compound Treatment: Transfer compound libraries using nanoliter-scale dispensers.

- Incubation: Incubate for predetermined time based on pharmacokinetic parameters.

- Endpoint Measurement: Utilize fluorescence, luminescence, or absorbance readouts.

- Data Analysis: Apply AI-driven analytics to identify hit compounds.

Validation: Benchmark against known active and inactive compounds; determine Z-factor for assay quality assessment.

Protocol 2: Drug Combination Analysis Using Web-Based Tools

Purpose: To precisely characterize synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effects of drug combinations in vivo.

Materials:

- In vivo model system

- Drug compounds at multiple dose levels

- Bioluminescence imaging system for tumor growth monitoring

- Web-based analysis tool (e.g., platform described in Romero-Becerra et al. [11])

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Treat animals with individual drugs and their combinations at multiple dose levels.

- Response Monitoring: Measure tumor growth via bioluminescence imaging at regular intervals.

- Data Input: Upload individual animal data to web-based platform.

- Statistical Analysis: Apply probabilistic model that accounts for experimental variability.

- Interaction Assessment: Calculate combination indices using appropriate reference models.

- Visualization: Generate dose-response surface plots and interaction landscapes.

Validation: The framework has been extensively benchmarked against established models and validated using diverse experimental datasets, demonstrating superior performance in detecting and characterizing synergistic interactions [11].

Visualization of Key Concepts

Drug Development Attrition Pathway

Drug Development Attrition Pathway: This diagram visualizes the progressive attrition of drug candidates through development phases, highlighting major failure points.

NAMs Implementation Workflow

NAMs Implementation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated approach of using multiple NAMs technologies in parallel for improved candidate selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for NAMs Implementation

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in NAMs |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-based Screening Systems (e.g., CIBER Platform) | Genome-wide studies of vesicle release regulators [9] | Functional genomics and target validation |

| Cell-Based Reporter Assays (e.g., INDIGO Melanocortin Receptor Assays) | Comprehensive toolkit to study receptor biology [9] | GPCR research and compound screening |

| Liquid Handling Systems (e.g., Beckman Coulter Cydem VT) | Automated screening and monoclonal antibody screening [9] | High-throughput compound screening |

| Organ-on-Chip Devices | Model drug-metabolism pathways and physiological microenvironments [12] | Physiologically relevant safety and efficacy testing |

| Web-Based Analysis Tools | Statistical framework for drug combination analysis [11] | Synergy assessment and experimental design |

| iPSC-Derived Cells | Human-relevant cells for disease modeling | Patient-specific drug response assessment |

| Phoslactomycin B | Phoslactomycin B, MF:C25H40NO8P, MW:513.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Piperkadsin A | Piperkadsin A, MF:C21H24O5, MW:356.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The limitations of traditional animal models constitute a significant driver of the 90% clinical failure rate that plagues drug development. While animal studies have contributed to medical advances, the evidence demonstrates that their predictive value for human outcomes is substantially limited by species differences, methodological flaws, and unrepresentative disease modeling.

New Approach Methodologies offer a promising path forward by providing human-relevant data at scale and with greater predictive accuracy. The rapid growth of the high-throughput screening market, increasing regulatory acceptance of NAMs, and demonstrated success of platforms using human tissues and advanced computational approaches collectively signal a transformation in how drug discovery and development may be conducted in the future.

For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing these technologies requires both a shift in mindset and investment in new capabilities. However, the potential payoff is substantial: reducing late-stage clinical failures, accelerating development timelines, and ultimately delivering more effective and safer therapies to patients. As validation of NAMs continues through initiatives like the Complement-ARIE partnership, the scientific community has an unprecedented opportunity to overcome the limitations that have stalled progress for decades.

The landscape of preclinical drug development is undergoing a profound transformation. Driven by legislative action and a concerted push from regulators, the industry is shifting from traditional animal models toward more predictive, human-relevant New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). This guide traces the regulatory momentum from the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 of 2022 to the detailed implementation roadmap released in 2025, providing a comparative analysis of the emerging toolkit that is redefining safety and efficacy evaluation.

The Regulatory Imperative: A Timeline of Change

The high failure rate of promising therapeutics in clinical trials—often due to a lack of efficacy or unexpected toxicity in humans—has highlighted a critical translation gap between animal models and human physiology [13]. This recognition has catalyzed a series of key regulatory developments.

The timeline below illustrates the major milestones in this regulatory shift:

- The Foundation (1938): The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) established the initial requirement for animal testing to ensure drug safety, creating the regulatory paradigm that would stand for decades [13] [14].

- The Legislative Catalyst (2022): The FDA Modernization Act 2.0 was signed into law, removing the mandatory stipulation for animal testing and explicitly allowing the use of non-animal methods (NAMs)—including cell-based assays, microphysiological systems, and computer models—to demonstrate safety and efficacy for investigational new drugs [13] [14]. It is crucial to note that this act did not ban animal testing but provided a legal alternative pathway [14].

- The Implementation Blueprint (2025): In April 2025, the FDA released a concrete roadmap outlining its plan to phase out animal testing requirements, starting with monoclonal antibodies and other drugs where animal models are particularly poor predictors of human response [15] [16]. This document aims to make animal testing "the exception rather than the norm" within a 3-5 year timeframe [16].

Comparative Analysis of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)

NAMs encompass a suite of innovative scientific approaches designed to provide human-relevant data. The table below compares the core categories of NAMs against traditional animal models.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Animal Models and Key NAMs Categories

| Model Category | Key Examples | Primary Advantages | Inherent Limitations | Current Readiness for Regulatory Submission |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Animal Models | Rodent (mice, rats), non-rodent mammals (dogs, non-human primates) | Intact, living system; study complex physiology and organ crosstalk [13] | Significant species differences in pharmacogenomics, drug metabolism, and disease pathology; poor predictive value for human efficacy (60% failure) and toxicity (30% failure) [13] | Long-standing acceptance; often required for a complete submission [14] |

| In Vitro & Microphysiological Systems (MPS) | 2D/3D cell cultures, patient-derived organoids, organs-on-chips [13] [17] | Human-relevance; use of patient-specific cells (iPSCs) to model disease and genetic diversity; can reveal human-specific toxicities [15] [13] | Difficulty recapitulating full organ complexity and systemic organ crosstalk; scaling challenges for high-throughput use [13] [16] | Encouraged in submissions; pilot programs ongoing for specific contexts (e.g., monoclonal antibodies); not yet fully validated for all endpoints [15] [16] |

| In Silico & Computational Models | AI/ML models for toxicity prediction, generative adversarial networks (GANs), computational PK/PD modeling [15] [13] | High-throughput; can analyze complex datasets and predict human-specific responses; can augment sparse real-world data [15] [13] | Dependent on quality and volume of training data; model validation and regulatory acceptance for critical decisions is an ongoing process [13] | Gaining traction for specific endpoints (e.g., predicting drug metabolism); used to augment, not yet replace, core safety studies [15] |

| In Chemico Methods | Protein assays for skin/eye irritancy, reactivity assays | Cost-effective, reproducible for specific, mechanistic endpoints | Limited in biological scope; cannot model complex, systemic effects in a living organism | Established use for certain toxicological endpoints (e.g., skin sensitization); accepted by regulatory bodies like OECD [17] |

Case Study: The Failure of TGN1412 (Theralizumab)

A stark example of the species difference is the case of the monoclonal antibody TGN1412. Preclinical testing in a BALB/c mouse model showed great efficacy for treating B-cell leukemia and arthritis. However, in a human Phase I trial, a dose 1/500th of the dose found safe in mice induced a massive cytokine storm, leading to organ failure and hospitalization in all six volunteers [13]. This tragedy underscores how differences in immune system biology between mice and humans can have catastrophic consequences, highlighting the critical need for human-relevant NAMs.

The Validation Pathway: Building Scientific Confidence for NAMs

For any NAM to be adopted in regulatory decision-making, it must undergo a rigorous process to demonstrate its reliability and relevance. This pathway, often termed "fit-for-purpose" validation, is the central thesis of modern regulatory science. The process is managed by multi-stakeholder groups like the FNIH's NAMs Validation & Qualification Network (VQN) [18] [8].

The workflow for validating a New Approach Methodology is a multi-stage, iterative process:

Detailed Experimental Protocol for a NAMs Pilot Study

The following protocol outlines the key steps for generating robust data for NAMs validation, using a microphysiological system (organ-on-a-chip) as an example.

Aim: To evaluate the predictive capacity of a human liver-on-a-chip model for detecting drug-induced liver injury (DILI) compared to traditional animal models and historical human clinical data.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Cell Sourcing and Differentiation:

- Protocol: Obtain commercially sourced human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) from a diverse donor pool (e.g., 10-50 lines) to capture population variability [13].

- Differentiation: Differentiate iPSCs into hepatocyte-like cells using a standardized, growth factor-driven protocol (e.g., sequential exposure to Activin A, BMP4, FGF2, and HGF over 15-20 days) [13].

- Quality Control: Confirm hepatocyte maturity via flow cytometry for albumin (>80% positive) and CYP3A4 activity measurement using a luminescent substrate.

Liver-on-a-Chip Assembly and Functional Validation:

- Protocol: Seed differentiated hepatocytes along with human endothelial and stellate cells into a multi-channel polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic device to create a 3D, perfused liver tissue mimic [13].

- Functional Assays: After a 5-day stabilization period, assess key liver functions: albumin secretion (ELISA), urea production (colorimetric assay), and cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4, CYP2C9) enzyme activity using probe substrates (e.g., luciferin-IPA) [17]. Compare baseline values to established primary human hepatocyte data.

Compound Testing and High-Content Phenotyping:

- Test Articles: Select a panel of 20-30 benchmark compounds with known clinical DILI outcomes (e.g., 10 hepatotoxicants, 10 non-hepatotoxicants).

- Dosing: Expose the liver-chips to a range of concentrations of each compound (including therapeutic C~max~) for up to 14 days, refreshing media/drug daily.

- Real-time Monitoring: Continuously monitor metabolic activity (via resazurin reduction) and release of damage biomarkers (e.g., ALT, AST) into the effluent.

- Endpoint Staining: At designated timepoints, fix and stain chips for high-content imaging: nuclei (Hoechst), actin (phalloidin), and apoptotic/necrotic markers (Annexin V/propidium iodide).

Multi-Omics Data Integration and Model Training:

- Protocol: Following treatment, extract RNA and protein from the chips for transcriptomic (RNA-seq) and proteomic analysis.

- Data Integration: Use bioinformatics pipelines to identify gene expression signatures and pathway perturbations (e.g., oxidative stress, steatosis, necrosis) associated with hepatotoxicity.

- AI/ML Analysis: Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., random forest) on the multi-parametric dataset (functional, imaging, omics) to distinguish hepatotoxic from non-toxic compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for NAMs Workflows

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced In Vitro Models

| Reagent / Material | Function in Workflow | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | The foundational cell source for generating patient-specific or diverse human tissues. | Commercially available from biobanks; should be well-characterized and from diverse genetic backgrounds [13]. |

| Specialized Cell Culture Media | Supports the growth, maintenance, and differentiation of cells in 2D, 3D, or organ-chip systems. | Defined, serum-free formulations tailored for specific cell types (e.g., hepatocyte, cardiomyocyte); often require specific growth factor cocktails [17]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Hydrogels | Provides a 3D scaffold that mimics the in vivo cellular microenvironment. | Products like Matrigel, collagen I, or synthetic PEG-based hydrogels; critical for organoid and 3D tissue formation [13]. |

| Microphysiological Systems (MPS) | The hardware platform that enables complex, perfused 3D tissue culture. | Commercially available organ-on-chip devices (e.g., from Emulate, Mimetas) with microfluidic channels and integrated sensors [13]. |

| Viability & Functional Assay Kits | Used to quantify cell health, metabolic activity, and tissue-specific function. | Kits for measuring ATP levels, albumin, urea, CYP450 activity, and cytotoxicity (LDH release) in a high-throughput compatible format [17]. |

| Barcoding & Multiplexing Tools | Enables tracking of multiple cell lines in a single "cell village" experiment for scaling and diversity studies. | Lipid-based or genetic barcodes that allow pooling of multiple iPSC lines, with subsequent deconvolution via single-cell RNA sequencing [13]. |

| Macarangin | Macarangin|Natural Compound|Research Use | High-purity Macarangin, a natural compound from Macaranga occidentalis. Studied for its antimicrobial and antiviral research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Glisoprenin E | Glisoprenin E|Inhibitor of Appressorium Formation | Glisoprenin E is a polyterpenoid that inhibits appressorium formation in Magnaporthe grisea. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human use. |

The regulatory momentum is unequivocal. The journey from the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 to the 2025 FDA Roadmap marks a decisive pivot toward a modern, human-biology-focused paradigm for drug development. While the transition will be phased and require extensive validation, the direction is clear. The scientific and regulatory framework is being built to replace, reduce, and refine animal testing with a suite of human-relevant NAMs that promise to improve patient safety, accelerate the delivery of cures, and ultimately make drug development more efficient and predictive. For researchers and drug developers, engaging with these new approaches and contributing to the validation ecosystem is no longer a niche pursuit but a strategic imperative for the future.

The adoption of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in biomedical research and drug development hinges on demonstrating their robustness and predictive capacity. A robust NAM is characterized by two core principles: it must be fit-for-purpose, meaning its design and outputs are scientifically justified for a specific application, and it must be grounded in human biology to enhance the translational relevance of findings. This guide objectively compares key methodological components for building and validating such NAMs, focusing on experimental and computational techniques for assessing the accuracy of molecular structures and quantitative analyses. We present supporting data and detailed protocols to aid researchers in selecting and implementing these critical validation strategies.

Comparative Analysis of NMR-Based Validation Methodologies

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy serves as a powerful tool for validating the structural and chemical output of NAMs, from characterizing synthesized compounds to probing protein structures in near-physiological environments. The table below compares three distinct NMR applications relevant to NAM development.

Table 1: Comparison of NMR Techniques for NAMs Validation

| Methodology | Key Measured Parameters | Application in NAMs | Throughput & Key Advantage | Quantitative Performance / Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental NMR Parameter Dataset [19] | - 775 nJCH coupling constants- 300 nJHH coupling constants- 332 1H & 336 13C chemical shifts | Benchmarking computational methods for 3D structure determination of organic molecules. | Medium; Provides a validated, high-quality ground-truth dataset for method calibration. | Identified a subset of 565 nJCH and 205 nJHH couplings from rigid molecular regions for reliable benchmarking. |

| ANSURR (Protein Structure Validation) [20] | - Backbone chemical shifts (HN, 15N, 13Cα, 13Cβ, Hα, C′)- Random Coil Index (RCI)- Rigidity from structure (FIRST) | Assessing the accuracy of NMR-derived protein structures by comparing solution-derived rigidity (RCI) with structural rigidity. | Low; Provides a direct, independent measure of protein structure accuracy in solution. | Correlation score assesses secondary structure; RMSD score measures overall rigidity. Accurate structures show high correlation and low RMSD scores. |

| pH-adjusted qNMR for Metabolites [21] | - 1H NMR signal integration- Quantum Mechanical iterative Full Spin Analysis (QM-HiFSA) | Simultaneous quantitation of unstable and isomeric compounds, like caffeoylquinic acids, in complex mixtures. | High; Offers a absolute quantification without identical calibrants and minimal sample preparation. | QM-HiFSA showed superior accuracy and reproducibility over conventional integration for quantifying chlorogenic acid and 3,5-di-CQA in plant extracts. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Creating a Benchmarking Dataset for Computational Methods

This protocol outlines the generation of a validated experimental dataset for benchmarking computational structure determination methods, as exemplified by Dickson et al. [19].

- Sample Preparation: Select a set of complex organic molecules. Prepare samples for NMR analysis in appropriate deuterated solvents.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire NMR spectra to obtain proton-carbon (nJCH) and proton-proton (nJHH) scalar coupling constants. Assign 1H and 13C chemical shifts.

- 3D Structure Determination: Determine the corresponding 3D molecular structures.

- Computational Validation: Calculate the same NMR parameters (coupling constants and chemical shifts) using Density Functional Theory (DFT) at a defined level of theory (e.g., mPW1PW91/6-311 g(dp)).

- Curation and Validation: Compare experimental and DFT-calculated values to identify and correct misassignments. Finally, identify and subset parameters from the rigid portions of the molecules, as these are most valuable for benchmarking.

Protocol 2: Validating Protein Structure Accuracy with ANSURR

The ANSURR method provides an independent validation metric for protein structures by comparing solution-state backbone dynamics inferred from chemical shifts to the rigidity of a 3D structure [20].

- Input Data Collection:

- Obtain the protein's backbone chemical shift assignments (HN, 15N, 13Cα, 13Cβ, Hα, C′).

- Obtain the 3D protein structure to be validated (e.g., an NMR ensemble).

- Calculate Experimental Rigidity (RCI): Process the backbone chemical shifts using the Random Coil Index (RCI) algorithm. This predicts the local flexibility of the protein backbone in solution.

- Calculate Structural Rigidity (FIRST): Analyze the 3D structure using the Floppy Inclusions and Rigid Substructure Topography (FIRST) software, which applies mathematical rigidity theory to the protein's constraint network (covalent bonds, hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions) to compute the probability that each residue is flexible.

- Comparison and Scoring:

- Calculate the correlation between RCI and FIRST profiles. This assesses whether secondary structure elements are correctly positioned (good correlation).

- Calculate the RMSD between the RCI and FIRST profiles. This measures whether the overall rigidity of the structure is accurate (low RMSD).

- Interpretation: Plot both scores on a graph. Accurate structures typically reside in the top-right corner (high correlation, low RMSD).

Protocol 3: Absolute Quantification of Metabolites via qNMR

This protocol describes a quantitative NMR method for analyzing complex mixtures of similar metabolites, such as caffeoylquinic acid derivatives, which are challenging for chromatography [21].

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the complex mixture (e.g., plant extract) in a deuterated solvent (e.g., methanol-d4). For pH-sensitive compounds, adjust the pH using a deuterated buffer to stabilize the analytes.

- qNMR Acquisition: Acquire a 1H NMR spectrum with optimal relaxation delay (D1 ≥ 5 x T1 of the slowest relaxing signal) to ensure accurate quantitative integration. Suppress the water signal if present.

- Quantification (Two Methods):

- Conventional Integration: Use an internal standard of known purity and concentration (e.g., dimethyl sulfone). Integrate the resolved signal from the standard and a target analyte, then calculate the analyte's concentration based on the ratio of integrals.

- QM-HiFSA (Quantum Mechanical Iterative Full Spin Analysis): Use a computer-assisted approach to iteratively generate a quantum-mechanically calculated 1H NMR spectrum that matches the experimental spectrum. The concentration of the target analyte is a fitted parameter in this iterative full spin analysis, offering high accuracy even in crowded spectral regions.

- Validation: Compare the results from both methods, with QM-HiFSA often providing superior accuracy and reproducibility for complex mixtures [21].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiments

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents | Provides the lock signal for NMR spectrometers and allows for the preparation of samples without interfering proton signals. | Methanol-d4, D2O, Chloroform-d [21]. |

| Internal Quantitative Standards | Provides a known reference signal for absolute quantification in qNMR. Must be of high, known purity and chemically stable. | Dimethyl sulfone, maleic acid, caffeine [21]. |

| NMR Parameter Dataset | A ground-truth dataset for validating and benchmarking computational chemistry methods for 3D structure determination. | Dataset of 775 nJCH and 300 nJHH couplings for 14 organic molecules [19]. |

| Rigidity Analysis Software (FIRST) | Performs rigid cluster decomposition on a protein structure to predict flexibility from its 3D atomic coordinates. | FIRST (Floppy Inclusions and Rigid Substructure Topography) software [20]. |

| Quantum Mechanics Analysis Software | Enables QM-HiFSA for highly accurate spectral analysis and quantification in complex mixtures by iterative full spin analysis. | Software such as "Cosmic Truth" [21]. |

Visualizing Workflows for NAM Validation

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows for the core validation methodologies discussed.

Protein Structure Validation with ANSURR

Quantitative NMR for Complex Mixtures

Ethical, Economic, and Efficiency Gains Driving Adoption

The adoption of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in biomedical research and regulatory science is being driven by a powerful convergence of ethical, economic, and efficiency imperatives. NAMs encompass a broad range of innovative, non-animal technologies—including advanced in vitro models, organs-on-chips, computational toxicology, and AI/ML analytics—used to evaluate the safety and efficacy of drugs and chemicals [17] [22]. This transition represents a paradigm shift from traditional animal testing toward more human-relevant, predictive, and efficient testing strategies. The compelling advantages across these three domains are accelerating the validation and integration of NAMs, positioning them as the future cornerstone of preclinical safety assessment.

Ethical Imperatives: Advancing the 3Rs and Beyond

The ethical drive to replace, reduce, and refine (the 3Rs) animal use in research has long been a guiding principle and now provides a foundation for understanding NAMs' central role in the industry's future [17]. Recent regulatory initiatives, such as the FDA's 2025 "Roadmap to Reducing Animal Testing in Preclinical Safety Studies," aim to make animal studies the exception rather than the rule [22]. This commitment extends beyond policy to practical implementation, with initial focus on monoclonal antibodies and eventual expansion to other biological molecules and new chemical entities [22]. By using human-relevant models, NAMs address not only ethical concerns but also fundamental questions about the biological relevance of animal models for human health assessments, creating a dual ethical-scientific imperative for their adoption [23] [24].

Economic Advantages: Quantifying the Value Proposition

The economic benefits of NAMs stem from their ability to lower costs across the drug development pipeline while reducing late-stage failures. Traditional animal studies are costly and time-consuming, but more significantly, they often prove poorly predictive of human outcomes [22]. The staggering statistic that over 90% of drugs that pass preclinical animal testing fail in human clinical trials—with approximately 30% due to unmanageable toxicities—represents an enormous financial burden on the pharmaceutical industry [22]. NAMs address this failure point by providing more human-relevant data earlier in the development process, enabling "failing faster" and avoiding costly late-stage failures and market withdrawals [22].

Table 1: Economic and Efficiency Comparison of NAMs vs. Traditional Animal Testing

| Parameter | Traditional Animal Testing | New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Costs | High (animal purchase, housing, care) | Lower (cell culture, reagents, equipment) |

| Study Duration | Months to years | Days to weeks |

| Throughput | Low | High to high-throughput |

| Predictive Accuracy for Humans | Limited (species differences) | Improved (human-based systems) |

| Late-Stage Attrition Rate | High (~90% failure rate in clinical trials) | Expected reduction via earlier, better prediction |

| Regulatory Data Acceptance | Established but questioned relevance | Growing acceptance via FDA roadmap, pilot programs |

Efficiency Gains: Enhancing Predictive Capacity and Speed

NAM technologies offer significant operational advantages through faster results, mechanistic insights, and improved reproducibility. The high-throughput capabilities and automation of many NAM platforms can dramatically accelerate data collection and decision-making cycles [22]. Furthermore, standardized in vitro systems can minimize variability common in animal models, improving predictive accuracy and data reliability [22]. Unlike animal models, NAMs can be easily adapted and scaled to assess different disease areas, drug candidates, and testing protocols, providing unprecedented flexibility in research design [22].

From a scientific perspective, NAMs provide deeper mechanistic understanding than traditional approaches. Many NAMs allow for real-time, functional readouts of cellular activity that can uncover the fundamental mechanisms of disease or toxicity [22]. This capability is enhanced through anchoring to Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs), which link molecular initiating events to adverse health outcomes through established biological pathways [23] [25]. This mechanistic foundation builds scientific confidence in NAM predictions beyond correlative relationships with animal data.

Validation and Regulatory Adoption: Building Scientific Confidence

Robust processes to establish scientific confidence are essential for regulatory acceptance of NAMs. A modern framework for validation focuses on key elements including fitness for purpose, human biological relevance, technical characterization, data integrity, and independent review [24]. Critical to this process is establishing a clear Context of Use (COU)—a statement fully describing the intended use and regulatory purpose of the NAM [23]. The validation process must be flexible enough to recognize that NAMs may provide information of equivalent or better quality and relevance than traditional animal tests, without necessarily generating identical data [23] [24].

Regulatory agencies worldwide are actively facilitating this transition. The EPA prioritizes NAMs to reduce vertebrate animal testing while ensuring protection of human health and the environment [25]. The FDA encourages sponsors to include NAMs data in regulatory submissions and has initiated pilot programs for biologics, with indications that strong non-animal safety data may lead to more efficient evaluations [22]. This shifting landscape makes early engagement with regulatory agencies a strategic imperative for sponsors incorporating NAMs into their testing strategies [22].

Experimental Approaches and Workflows in NAMs

NAM experimental protocols leverage human biology to create more predictive testing systems. The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized approach for evaluating compound effects using human iPSC-derived models:

Diagram 1: Generalized workflow for compound testing using human iPSC-derived models in NAMs. The process leverages human-relevant cells and real-time functional measurements to predict compound effects.

Key technologies enabling these experimental approaches include microphysiological systems (organs-on-chips), patient-derived organoids, and computational models [17]. These systems can incorporate genetic diversity from human population-based cell panels, potentially enabling identification of susceptible subpopulations—a significant advantage over traditional animal models [23].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NAMs Implementation

| Reagent / Material | Function in NAMs Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Human iPSCs | Source for generating patient-specific human cells | Differentiate into cardiomyocytes, neurons, hepatocytes |

| Specialized Media & Growth Factors | Support cell differentiation and maintenance | Culture organoids, microphysiological systems |

| Maestro MEA Systems | Measure real-time electrical activity without labels | Cardiotoxicity and neurotoxicity assays |

| Impedance-Based Analyzers | Track cell viability, proliferation, and barrier integrity | Cytotoxicity, immune response, barrier models |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Devices | Mimic human organ physiology and microenvironment | Disease modeling, drug testing, personalized medicine |

| OMICS Reagents | Enable genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics analyses | Mechanistic studies, biomarker discovery |

The adoption of New Approach Methodologies represents a transformative shift in toxicology and drug development, driven by compelling and interconnected ethical, economic, and efficiency gains. Ethically, NAMs advance the 3Rs principles while addressing growing concerns about the human relevance of animal data. Economically, they offer substantial cost savings through reduced animal use, faster testing cycles, and potentially lower late-stage attrition rates. Operationally, NAMs provide superior efficiency through higher throughput, human relevance, and deeper mechanistic insights. As regulatory frameworks evolve to accommodate these innovative approaches, and as validation frameworks establish scientific confidence based on human biological relevance rather than comparison to animal data, NAMs are poised to become the cornerstone of next-generation safety assessment and drug development.

NAM Technologies in Action: From Organ-on-Chip to AI and Integrated Testing Strategies

The field of preclinical drug testing is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving away from traditional animal models toward more predictive, human-relevant New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). This shift, driven by scientific, ethical, and regulatory pressures, aims to address the high failure rates of drugs in clinical trials, where lack of efficacy and unforeseen toxicity are major contributors [26]. NAMs encompass a suite of innovative tools, including advanced in vitro systems such as microphysiological systems (MPS), organoids, and other complex in vitro models (CIVMs) [17] [1]. These technologies are designed to better recapitulate human physiology, providing more accurate data on drug safety and efficacy.

Regulatory bodies worldwide are actively encouraging this transition. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Modernization Act 2.0, for instance, now allows drug applicants to use alternative methods—including cell-based assays, organ chips, and computer modeling—to establish a drug's safety and effectiveness [27] [28]. Similarly, the European Parliament has passed resolutions supporting plans to accelerate the transition to non-animal methods in research and regulatory testing [27]. This evolving landscape frames the critical need to objectively compare the capabilities of leading advanced in vitro systems: traditional 3D cell-based assays, organoids, and MPS.

The quest for more physiologically relevant in vitro models has driven the development of increasingly complex systems. The following table provides a high-level comparison of the core technologies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Advanced In Vitro Systems

| Feature | Advanced 3D Cell-Based Assays (e.g., Spheroids) | Organoids | Microphysiological Systems (MPS)/Organ-on-a-Chip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensionality & Structure | 3D cell aggregates; simple architecture [27] | 3D structures mimicking organ anatomy and microstructure [29] | 3D structures within engineered microenvironments [26] |

| Key Advantage | Scalability, cost-effectiveness for high-throughput screening [30] | High biological fidelity; patient-specificity [26] | Incorporation of dynamic fluid flow and mechanical forces [26] [29] |

| Physiological Relevance | Basic cell-cell interactions; recapitulates some tissue properties [27] | Recapitulates developmental features and some organ functions [29] | Recapitulates tissue-tissue interfaces, vascular perfusion, and mechanical cues [26] [28] |

| Cell Source | Cell lines, primary cells [30] | Pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), adult stem cells, patient-derived cells [26] [29] | Cell lines, primary cells, iPSC-derived cells [28] |

| Throughput & Scalability | High | Medium to Low | Low to Medium [28] |

| Reproducibility & Standardization | Moderate to High | Challenging due to complexity and batch variability [26] [27] | Challenging; requires rigorous quality control [27] |

A deeper, quantitative comparison of their performance in critical applications further elucidates their respective strengths and limitations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of In Vitro Systems in Key Applications

| Application / Performance Metric | Advanced 3D Cell-Based Assays | Organoids | MPS/Organ-on-a-Chip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicology Prediction | |||

| Â Â Â Â Predictive Accuracy for Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) | Good | High (using patient-derived cells) [26] | 87% correct identification of hepatotoxic drugs [28] |

| Drug Efficacy Screening | |||

| Â Â Â Â Utility in Personalized Oncology | Moderate | High; used for large-scale functional screens of therapeutics [28] | Emerging |

| Model Complexity | |||

| Â Â Â Â Ability to Model Multi-Organ Interactions | Not possible | Not possible | Possible via multi-organ chips [26] |

| Representation of Human Biology | |||

| Â Â Â Â Presence of Functional Vasculature | No | Limited, often missing [28] | Yes, can emulate pulsatile blood flow [29] |

Experimental Data and Validation Studies

Case Study: Liver-Chip for Predictive Toxicology

A landmark study evaluating a human Liver-Chip demonstrated its superior predictive value for drug-induced liver injury (DILI). The study tested 22 hepatotoxic drugs and 5 non-hepatotoxic drugs with known clinical outcomes. The Liver-Chip correctly identified 87% of the drugs that cause liver injury in patients, showcasing a high level of human clinical relevance [28]. This performance is significant because DILI is a major cause of drug failure during development and post-market withdrawal. The chip model successfully recapitulated complex human responses, such as the cytokine release syndrome observed with the therapeutic antibody TGN1412, which had not been detected in prior preclinical monkey studies [31].

Case Study: Organoids in Personalized Cancer Drug Discovery

In the realm of oncology, patient-derived tumor organoids are proving to be powerful tools for biomarker discovery and drug efficacy testing. A large-scale functional screen using patient-derived organoids from heterogenous colorectal cancers successfully identified a bispecific antibody (MCLA-158) with efficacy in epithelial tumors. This research, published in Nature Cancer, contributed to the therapeutic reaching clinical trials within just five years from initial development [28]. This case highlights the potential of organoid technology to accelerate the translation of discoveries from the lab to the clinic, particularly in personalized medicine by retaining the patient's genetic and epigenetic makeup [26].

Validation within the Regulatory Framework

The validation of these systems is increasingly supported by regulatory agencies. The FDA's newly created iSTAND pilot program provides a pathway for qualifying novel tools like organ-on-chip models for regulatory decision-making [28]. Furthermore, the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) has published work substantiating that data derived from certain MPS platforms are appropriate for use in drug safety and metabolism applications, evidencing enhanced performance over standard techniques [31]. This regulatory acceptance is a critical step in the broader adoption of NAMs.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Generating iPSC-Derived Retinal Organoids

The generation of organoids from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) recapitulates key stages of organ development [29].

- Maintenance of Human iPSCs: Culture human iPSCs on a feeder-free layer with essential reprogramming factors (e.g., Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) and maintain in mTeSR or equivalent medium [29].

- Initial Differentiation: To initiate retinal differentiation, transfer iPSCs to low-attachment plates to form embryoid bodies. Culture in neural induction medium supplemented with growth factors (e.g., N2, B27) and small molecules to inhibit BMP and TGF-β signaling pathways.

- 3D Matrigel Embedding: After several days, embed the embryoid bodies in Matrigel or a similar extracellular matrix (ECM) substitute to provide a 3D environment that supports morphogenesis.

- Stepwise Differentiation and Self-Assembly: Culture the embedded structures in a sequence of differentiation media that promote the formation of the neuroretinal cup. The cells undergo self-assembly, driven by intrinsic developmental programs, over a period of 2-3 weeks.

- Long-term Maturation and Analysis: Maintain the developing retinal organoids in suspension culture for several months to allow for full cellular differentiation and stratification. The resulting organoids can be analyzed via immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and functional assays to confirm the presence of key retinal cell types and structures [29].

Protocol for a Standard MPS (Organ-on-a-Chip) Experiment

This protocol outlines the key steps for operating a typical polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based MPS, such as a liver-on-chip model [29].

Device Fabrication and Sterilization:

- Fabricate the microfluidic device using soft lithography with PDMS, a silicone-based polymer chosen for its optical transparency and gas permeability [29].

- Bond the PDMS layer to a glass substrate using oxygen plasma treatment.

- Sterilize the entire device using autoclaving or UV irradiation.

ECM Coating and Cell Seeding:

- Introduce an ECM protein solution (e.g., collagen I, fibronectin) into the microfluidic channels and incubate to allow coating of the membrane surfaces.

- Trypsinize and prepare a cell suspension of primary human hepatocytes or other relevant cell types at a high density (e.g., 10-20 million cells/mL).

- Seed the cells into the designated tissue chamber of the device. Allow cells to adhere and form a confluent layer under static conditions for several hours or overnight.

Perfusion Culture and Dosing:

- Connect the device to a perfusion system or pump to initiate a continuous, low-flow rate of culture medium (e.g., 50-100 µL/hour) through the microchannels.

- Maintain the system under perfusion for several days to weeks to allow the formation of a stable and functional tissue barrier.

- For experimental dosing, introduce the drug or test compound at the desired concentration into the perfusion medium. The flow can emulate interstitial flow or blood luminal flow, depending on the chip design [29].

Real-time Monitoring and Endpoint Analysis:

- Utilize the optical transparency of the PDMS device for real-time, live-cell imaging of the tissue response using phase-contrast or fluorescence microscopy.

- At the experiment endpoint, collect effluent for analysis of secreted biomarkers (e.g., albumin, cytokines) and fix the tissue for downstream histological (e.g., H&E staining) or molecular analyses (e.g., RNA-Seq) [28] [29].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

Logical Workflow for NAM Validation and Application

The following diagram outlines the critical pathway for developing, validating, and applying advanced in vitro systems within the NAMs framework.

Technology Integration and Data Synthesis

This diagram illustrates how different NAMs can be integrated to form a more comprehensive testing strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of advanced in vitro models relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components for building these systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced In Vitro Models

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Self-renewing, patient-specific cells that can differentiate into any cell type, serving as the foundation for human-relevant models [29]. | Generating patient-derived organoids for disease modeling and personalized drug screening [28]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Substitutes (e.g., Matrigel) | A basement membrane extract that provides a 3D scaffold to support cell growth, differentiation, and self-organization [29]. | Embedding embryoid bodies to support the formation of complex 3D organoid structures [29]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | A silicone-based polymer used to fabricate microfluidic devices; valued for its optical clarity, gas permeability, and ease of molding [29]. | Creating the core structure of organ-on-a-chip devices for perfusion culture and real-time imaging [29]. |

| Specialized Culture Media & Growth Factors | Chemically defined media and cytokine supplements that direct stem cell differentiation and maintain tissue-specific function in 3D cultures. | Promoting the stepwise differentiation of iPSCs into retinal, hepatic, or cerebral organoids [29]. |

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | A key signaling protein that stimulates the growth of blood vessels (angiogenesis). | Promoting the formation of vascular networks within organoids or MPS to enhance maturity and enable nutrient delivery [28]. |

| Pyrrocidine A | Pyrrocidine A|For Research Use Only | Pyrrocidine A is a macrocyclic alkaloid with potent apoptosis-inducing and antibacterial activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Glisoprenin C | Glisoprenin C, MF:C45H84O8, MW:753.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |