Read-Across in Chemical Safety: A Modern Framework for Data Gap Filling and Regulatory Acceptance

This article provides a comprehensive overview of read-across approaches for chemical safety assessment, exploring their foundational principles, methodological applications, and optimization strategies.

Read-Across in Chemical Safety: A Modern Framework for Data Gap Filling and Regulatory Acceptance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of read-across approaches for chemical safety assessment, exploring their foundational principles, methodological applications, and optimization strategies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it examines how structural and biological similarity can predict toxicity for data-poor chemicals. The content covers integrative frameworks combining traditional read-across with New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), addresses common implementation challenges, and analyzes validation criteria and global regulatory acceptance patterns to support confident application in biomedical and chemical development.

Read-Aross Fundamentals: From Chemical Similarity to Biological Plausibility

Read-across is a defined methodology used in chemical risk assessment to predict the (eco)toxicological properties of a target substance for which little or no experimental data exists by using information from one or several similar, well-characterized substances, known as source substances [1] [2]. It functions as a data gap-filling strategy within a broader weight-of-evidence evaluation [3] [2]. As a New Approach Methodology (NAM), read-across is part of a transformative shift in toxicology, aiming to increase the efficiency of safety assessments, lower testing costs, reduce reliance on animal testing, and improve the human relevance of data [3].

The fundamental principle underpinning read-across is that structurally similar compounds are likely to exhibit similar biological properties and toxicological effects [3]. This principle allows risk assessors to make informed predictions about the safety of a data-poor target substance. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has developed formal guidance to standardize the application of read-across in food and feed safety risk assessment, detailing a structured workflow to ensure transparency and scientific robustness [2]. This guide objectively compares the core principles, regulatory expectations, and practical implementation of the read-across approach against traditional toxicological methods.

Core Principles and Definitions

The practice of read-across is built upon several key concepts and a structured workflow. Understanding this terminology is essential for researchers and regulators.

Foundational Terminology

- Target Substance: The data-poor chemical for which properties are being predicted [1] [2].

- Source Substance: The data-rich chemical(s) used to predict the properties of the target substance [1] [2].

- Analogue Approach: Using data from one or only a few source substances for prediction [3].

- Grouping Approach: Applying data from a larger subset of related substances where toxicological properties follow a predictable trend [3].

- Uncertainty Assessment: A critical evaluation of the uncertainties introduced by the read-across prediction and whether they can be reduced to tolerable levels [1] [2].

The Read-Across Workflow

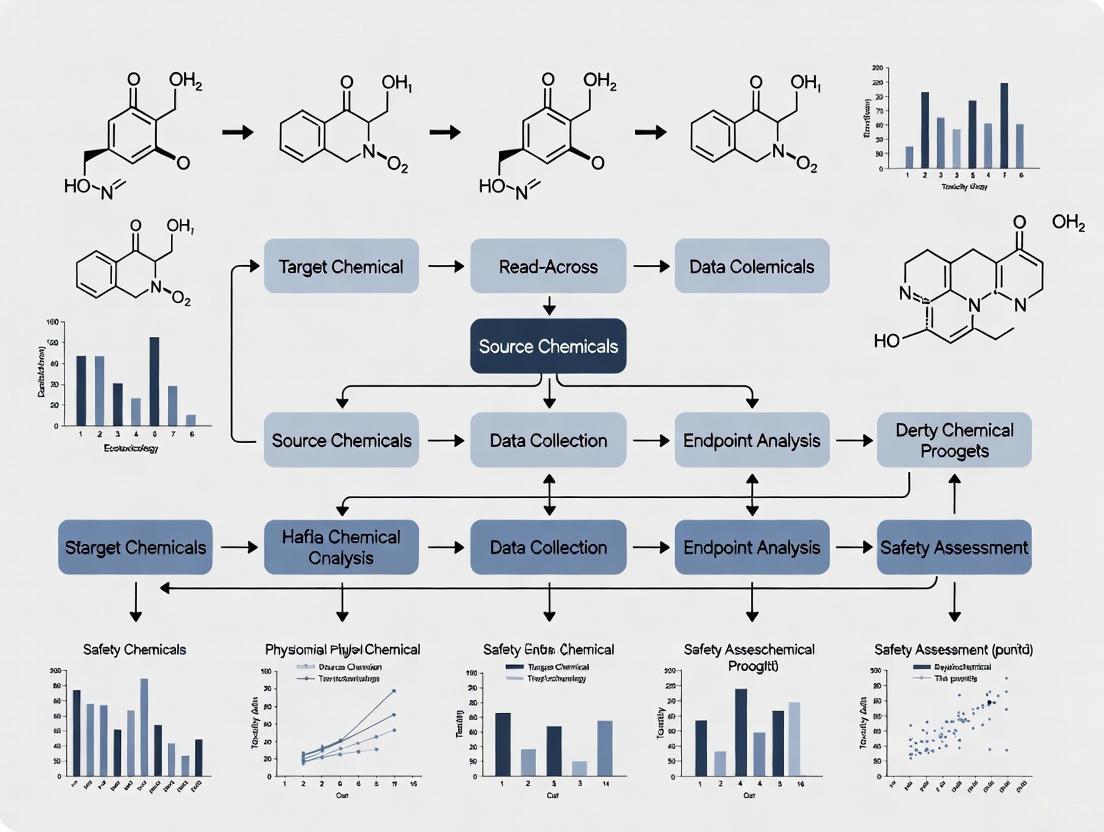

The EFSA guidance outlines a systematic workflow to ensure reliable and transparent assessments [2]. The following diagram visualizes this multi-step process, which forms the logical backbone of a robust read-across assessment.

Regulatory Context and Guidance

The regulatory landscape for read-across is evolving, with significant developments in the European Union setting a precedent for its standardized application.

Key Regulatory Frameworks

Regulatory bodies provide structured frameworks to guide the application of read-across, emphasizing scientific rigor and transparency.

- EFSA Guidance (2025): EFSA's newly developed guidance provides a step-by-step workflow for read-across in food and feed safety assessment. It places a particular emphasis on integrating New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) to strengthen the scientific justification and on conducting a thorough uncertainty analysis. The ultimate goal is to equip risk assessors with a comprehensive framework for carrying out systematic and transparent assessments [2].

- ECHA RAAF and OECD Guidance: The European Chemicals Agency's Read-Across Assessment Framework (RAAF) and the OECD's guidance on the grouping of chemicals (2007, revised 2014) provide foundational principles and practical steps that have informed regulatory practice for years [1].

- Global Context: While EFSA is at the forefront of formalizing guidance, other jurisdictions are also applying read-across principles. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives incorporates read-across-like approaches within its weight-of-evidence evaluations. The United States and Canada currently apply read-across on a case-by-case basis without a formalized framework comparable to the EU's [3].

Regulatory Acceptance and Challenges

A primary challenge in regulatory submission is adequately demonstrating that the source and target substances are sufficiently similar for the specific endpoint being assessed, as minor structural differences can lead to significant changes in toxicological behavior [3]. Regulators expect read-across to be supported not only by structural similarity but also by mechanistic evidence, such as data on the mode of action or kinetics [3]. Consequently, stand-alone evidence from read-across may not be considered sufficient to conclude on the toxicity of a target substance; it is generally more acceptable when presented as part of a weight-of-evidence approach in conjunction with other lines of evidence (e.g., in vivo, in vitro, OMICs data) [1].

Practical Implementation and Comparison with Traditional Methods

Transitioning from principle to practice requires specific tools and an understanding of how read-across compares to traditional toxicological testing.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The following table details key resources and tools that are essential for developing and justifying a read-across assessment.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Read-Across Assessments

| Tool / Resource Name | Function / Purpose | Example Platforms / Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | For searching structurally similar compounds and accessing experimental data. | eChemPortal, CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [3] |

| Grouping & Read-Across Tools | Software to systematically compare molecular structures, properties, and toxicity data. | OECD QSAR Toolbox, CEFIC AMBIT tool, EPA Analog Identification Methodology (AIM) Tool [3] |

| In Vitro Data Platforms | Provide mechanistic toxicology data to bolster biological plausibility of the read-across. | Tox21, ToxCast [3] |

| Uncertainty Analysis Template | A structured framework to document and evaluate uncertainties in the assessment. | Provided in EFSA's draft guidance [3] |

Comparative Analysis: Read-Across vs. Traditional Animal Testing

A objective comparison of the performance and characteristics of read-across against traditional animal testing reveals distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Read-Across and Traditional Animal Testing

| Feature | Read-Across Approach | Traditional Animal Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Predicts properties based on similarity to known substances [3]. | Directly measures effects in a live animal model. |

| Primary Objective | To fill data gaps without conducting new animal tests [3]. | To generate hazard data for a specific substance. |

| Data Output | Predicted data, with associated uncertainties [1]. | Empirical experimental data. |

| Time Requirement | Generally faster, leveraging existing data [3]. | Can take months to years per substance. |

| Financial Cost | Lower, as it avoids costly in vivo studies [3]. | Very high, due to husbandry and procedural costs. |

| Animal Use | Significantly reduces or eliminates animal use [3]. | High reliance on animal models. |

| Human Relevance | Can be enhanced by integrating human-relevant NAMs data [3]. | Limited by interspecies differences. |

| Key Challenge | Justifying similarity and managing uncertainty to gain regulatory acceptance [3] [1]. | Ethical concerns, cost, time, and translatability to humans. |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Evolving, guided by new frameworks (e.g., EFSA 2025); requires robust justification [3] [2]. | Well-established and historically standardized. |

Read-across is a scientifically sound and practical approach for chemical safety assessment, defined by its core principle of leveraging data from similar substances to fill knowledge gaps. Its structured workflow, as detailed in EFSA's 2025 guidance, emphasizes problem formulation, rigorous substance characterization, and critical uncertainty assessment to ensure reliable and transparent predictions [2]. While the approach offers significant advantages in reducing animal testing and accelerating the assessment process, its successful application and regulatory acceptance depend on a robust justification of similarity, often supported by integrating data from New Approach Methodologies. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the principles and practices of read-across is increasingly essential for navigating the future landscape of evidence-based chemical safety research.

The Evolution from Traditional to Integrative Read-Across Approaches

Read-across is a widely used data gap-filling technique within category and analogue approaches for regulatory purposes, playing a critical role in chemical safety assessment under frameworks such as the European Union's Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) regulation [4] [5]. The fundamental principle underpinning traditional read-across is the chemical similarity principle, which posits that chemically similar compounds are likely to exhibit similar biological effects and toxicity profiles [4]. This principle has provided the foundation for predicting chemical-induced responses based primarily on chemical structure alone, enabling hazard assessment without the need for extensive animal testing [4] [5].

Despite its regulatory acceptance and widespread application—evidenced by its use in up to 75% of analyzed REACH dossiers for at least one endpoint—traditional read-across faces significant challenges [5]. The accuracy of predictions based solely on chemical structural similarity often proves inadequate due to the complex mechanisms of toxicity underlying many adverse outcomes [4] [6]. Regulatory acceptance remains a major hurdle primarily due to the lack of objectivity and clarity about how to practically address uncertainties in what has largely been a subjective expert judgment-driven assessment [5].

This article traces the evolution from traditional chemical structure-based read-across to more advanced integrative approaches that combine chemical structural information with biological activity data. We will objectively compare the performance of these methodologies, provide detailed experimental protocols, and analyze how the integration of multiple data streams addresses the limitations of traditional approaches while enhancing prediction accuracy and regulatory acceptance.

Traditional Read-Across Approaches

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Traditional read-across approaches rely exclusively on chemical structural similarity to predict the toxicity of a target compound by inferring from structurally similar source chemicals with available toxicity data [4] [5]. The methodological foundation involves identifying a set of structural analogues and using their known toxicological properties to estimate the properties of the target chemical. This process typically employs chemical descriptors and similarity metrics to quantify the degree of structural resemblance between compounds [4].

The quantitative foundation for traditional read-across predictions is expressed in the following equation, where the predicted activity of a compound (Apred) is calculated from the similarity-weighted aggregate of the activities Ai of k nearest neighbors:

Equation 1: Traditional Read-Across Prediction

In this equation, Si represents the pairwise Tanimoto similarity between the target molecule and its ith neighbor, calculated from chemical descriptor space using the Jaccard distance [4]. The similarity-weighted aggregate ensures that the activities of more similar neighbors receive higher weights when calculating the predicted activity, providing a quantitative basis for what has often been treated as a qualitative assessment.

Applications and Regulatory Context

The application of traditional read-across has been particularly valuable in regulatory contexts where data gaps exist for specific endpoints. Under the REACH regulation, more than 20% of high production volume chemicals submitted for the first deadline relied on read-across for hazard information on various toxicity endpoints necessary for registration [4]. Similarly, a comparable proportion of High Production Volume chemicals submitted to the US EPA under the Toxic Substances Control Act have been evaluated using read-across approaches [5].

The OECD QSAR Toolbox represents one of the most widely used implementations of traditional read-across methodology, enabling users to identify structural analogues and fill data gaps through systematic similarity searching and grouping [4] [5]. Other software tools such as ToxMatch and ToxRead further facilitate nearest neighbor predictions using different similarity indices, providing the toxicology community with practical resources for implementing read-across in various decision contexts [5].

Limitations and Uncertainties

Despite its utility, traditional read-across faces several significant limitations that impact its predictive accuracy and regulatory acceptance. The approach fundamentally struggles with addressing complex mechanisms of toxicity that cannot be adequately captured by structural similarity alone [4] [6]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when predicting complex in vivo outcomes from chemical structure, where similar structures may exhibit different metabolic pathways or biological interactions.

The subjective nature of analogue selection and similarity assessment introduces substantial variability and uncertainty into predictions [5]. Without objective criteria for defining similarity thresholds and selecting appropriate analogues, different experts may arrive at divergent read-across conclusions for the same target chemical, undermining regulatory confidence. Furthermore, traditional approaches offer limited capability for mechanistic interpretation, as they lack the biological context necessary to explain why certain structural features correlate with specific toxicological outcomes [4].

The Emergence of Integrative Chemical-Biological Approaches

Conceptual Foundation and Scientific Rationale

The limitations of traditional read-across have spurred the development of integrative approaches that combine chemical structural information with biological activity data. The conceptual foundation for these methods rests on the recognition that toxicity pathways and adverse outcome pathways provide a mechanistic bridge between chemical structure and toxicological effects that cannot be fully captured by structural similarity alone [5]. By incorporating biological response data, these approaches aim to enhance the biological relevance of read-across predictions while reducing uncertainty.

Integrative methods leverage the growing availability of high-throughput screening data from programs such as ToxCast and the Toxicogenomics Project-Genomics Assisted Toxicity Evaluation system (TG-GATES) [4] [5] [7]. These data streams provide information on biological responses at molecular and cellular levels that can serve as indicators of potential toxicity mechanisms, offering a complementary dimension to traditional structural similarity assessments [4]. The integration of chemical and biological information enables a more comprehensive characterization of a chemical's potential hazard, moving beyond what can be inferred from structure alone.

Key Methodological Developments

The Chemical-Biological Read-Across (CBRA) approach represents a significant methodological advancement in integrative read-across [4] [6]. This approach infers each compound's toxicity from those of both chemical and biological analogs, with similarities determined by the Tanimoto coefficient applied to both descriptor types [4]. The CBRA prediction is calculated using an expanded version of the traditional read-across equation:

Equation 2: Chemical-Biological Read-Across Prediction

This equation incorporates both biological neighbors (kbio) and chemical neighbors (kchem) in a unified similarity-weighted prediction framework [4]. The method employs radial plots to visualize the relative contribution of analogous chemical and biological neighbors, enhancing the transparency and interpretability of predictions [4] [6].

Another significant development is the Generalized Read-Across (GenRA) approach, which provides a systematic framework for predicting toxicity across structurally similar neighborhoods in large chemical libraries [5]. This method enables objective evaluation of read-across performance using chemical structure and bioactivity information to define local validity domains—specific sets of nearest neighbors used for prediction [5] [8].

Experimental Basis for Biological Data Integration

The integration of biological data in read-across has been enabled by advances in high-throughput screening technologies that allow comprehensive profiling of chemical effects on biological systems. The ToxCast program and related initiatives have generated bioactivity data for thousands of chemicals across hundreds of assay endpoints, capturing effects on diverse biological targets and pathways [5] [7]. These data provide a rich source of biological descriptors for integrative read-across.

Specific biological data types used in integrative read-across include gene expression profiling from toxicogenomics studies, cytotoxicity screening data measuring intracellular ATP and caspase-3/7 activation, and targeted assays measuring specific pathway activities [4] [7]. For example, the study by Lock et al. screened 240 compounds across 81 human lymphoblast cell lines, measuring both cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction to generate biological response profiles that capture interindividual variability in chemical susceptibility [7].

Table 1: Data Types Used in Integrative Read-Across Approaches

| Data Type | Specific Endpoints | Example Sources | Application in Read-Across |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression | 2,923 transcripts from TG-GATES | Toxicogenomics Project [4] | Hepatotoxicity prediction |

| Cytotoxicity Screening | Intracellular ATP, caspase-3/7 activation | ToxCast, qHTS [4] [7] | Acute toxicity classification |

| Pathway-Based Assays | 821 ToxCast assay endpoints | ToxCast Program [5] | Mechanistic profiling for various toxicity endpoints |

| Chemical Descriptors | Dragon descriptors, structural fingerprints | Dragon Software, RDKit [4] [8] | Structural similarity assessment |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Design for Method Comparison

Rigorous comparison of traditional and integrative read-across approaches requires standardized evaluation across multiple toxicity endpoints and chemical domains. Low et al. conducted a comprehensive assessment using four distinct data sets with different toxicity endpoints: sub-chronic hepatotoxicity (127 compounds from TG-GATES), hepatocarcinogenicity (132 compounds from DrugMatrix), mutagenicity (185 compounds from CCRIS), and acute lethality (122 compounds with rat oral LD50 data) [4]. This experimental design enabled direct comparison of classification accuracy between traditional read-across (using chemical descriptors alone) and CBRA (using both chemical and biological descriptors).

Similarly, the GenRA framework was systematically evaluated for predicting up to ten different in vivo repeated dose toxicity study types using a set of 1778 chemicals from the ToxCast library [5] [8]. The approach utilized 3239 different chemical structure descriptors supplemented with outcomes from 821 in vitro assays, with prediction performance assessed for 600 chemicals with in vivo data [5] [8]. This large-scale evaluation provided robust statistical power for comparing method performance across diverse chemical spaces and toxicity endpoints.

Quantitative Performance Assessment

The comparative performance assessment reveals consistent advantages for integrative read-across approaches across multiple toxicity endpoints. In the CBRA study, the integrated chemical-biological approach demonstrated superior classification accuracy compared to methods using either chemical or biological descriptors alone [4] [6]. The performance advantage was particularly notable for complex endpoints such as hepatotoxicity and hepatocarcinogenicity, where mechanisms involve multiple biological pathways that cannot be fully captured by structural alerts alone.

The GenRA evaluation demonstrated that incorporating bioactivity descriptors from ToxCast assays improved prediction performance for many in vivo toxicity endpoints compared to using chemical descriptors alone [5]. This systematic analysis established a performance baseline for read-across predictions and highlighted the value of bioactivity data in reducing prediction uncertainty, particularly for data-poor chemicals where structural analogues are limited or insufficiently similar.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Read-Across Approaches Across Different Endpoints

| Toxicity Endpoint | Traditional RA (Chem Only) | Biological Similarity Only | Integrative CBRA | Key Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatotoxicity | Moderate accuracy | Moderate accuracy | High accuracy | CBRA exhibited consistently high external classification accuracy [4] |

| Hepatocarcinogenicity | Variable performance | Improved over chemical | Most reliable | Biological data provided complementary predictive information [4] |

| Mutagenicity | Good performance | Good performance | Enhanced performance | Both approaches benefited from integration [4] |

| Acute Lethality | Moderate accuracy | Moderate accuracy | Substantial improvement | Cytotoxicity profiles enhanced prediction [4] |

| Repeated Dose Toxicity | Limited applicability | Mechanistic relevance | Uncertainty reduction | Bioactivity data addressed key uncertainties [5] |

Uncertainty and Applicability Domain Considerations

A critical aspect of performance comparison involves assessing uncertainty and defining applicability domains for different read-across approaches. Traditional read-across typically defines applicability based on chemical structural similarity within a local validity domain [5]. While this approach identifies structurally related analogues, it may miss important biological considerations that affect toxicity potential.

Integrative approaches enable a more comprehensive definition of applicability domains that incorporates both chemical and biological similarity [4] [5]. This expanded domain characterization helps identify situations where structural similarity may not translate to similar biological activity, or conversely, where structurally diverse chemicals may share common toxicity mechanisms through different structural features. The transparency of the CBRA approach, aided by radial plots showing the relative contribution of chemical and biological neighbors, facilitates more informed uncertainty assessment by explicitly representing the evidence basis for predictions [4] [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chemical Descriptor Processing and Similarity Assessment

The experimental foundation for both traditional and integrative read-across begins with comprehensive chemical structure curation and descriptor calculation. The standard protocol involves:

Structural standardization: Chemical structures undergo rigorous curation procedures including standardization of representation, removal of salts and duplicates, and filtering of problematic structures (e.g., metal-containing compounds or those with molecular weight >2000) [4] [5].

Descriptor calculation: Dragon software (v.5.5 or later) is typically used to compute a comprehensive set of chemical descriptors capturing diverse structural and physicochemical properties [4]. Alternative approaches may employ extended-connectivity fingerprints or other structural representation methods [8].

Descriptor preprocessing: All chemical descriptors undergo range scaling to values between 0 and 1, followed by removal of low-variance descriptors (standard deviation <10^(-6)) and highly correlated descriptors (pairwise r² >0.9) to reduce dimensionality and minimize multicollinearity [4].

Similarity calculation: Pairwise similarity between compounds is quantified using the Tanimoto coefficient, derived from Jaccard distance calculations across the descriptor space [4]. The similarity values are normalized between 0 and 1, with 1 indicating identical pairs.

Biological Data Generation and Processing

The generation of biological descriptors for integrative read-across follows standardized protocols tailored to specific assay technologies:

Gene Expression Profiling (TG-GATES Protocol):

- Array processing: Rat or human in vivo or in vitro systems are exposed to chemicals, followed by RNA extraction and hybridization to microarrays (e.g., 31,042 probe arrays) [4].

- Data filtering: Probes that are consistently not expressed or show no change between treated and vehicle control groups are removed [4].

- Feature selection: Transcripts are selected based on fold change (>1.5) and statistical significance (false discovery rate <0.05), followed by removal of low-variance transcripts and highly correlated pairs (r²>0.9) [4].

- Descriptor formation: The final set of transcripts (e.g., 2,923 in the TG-GATES study) are range-scaled and used as biological descriptors for similarity assessment [4].

Cytotoxicity Screening (qHTS Protocol):

- Cell culture: Human lymphoblast cell lines (81 from CEPH trios) are cultured under standardized conditions and seeded into 1536-well assay plates [7].

- Chemical exposure: Cells are exposed to 12 concentrations of each chemical (0.26nM–46.0μM) to generate comprehensive concentration-response profiles [7].

- Endpoint measurement: Cytotoxicity is assessed via CellTiter-Glo assay measuring intracellular ATP after 40 hours; apoptosis is measured via Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay after 16 hours [7].

- Data processing: Concentration-response data are fitted to a Hill equation, with curve classification (active, nonactive, inconclusive) and calculation of potency metrics (curve P values) [7].

- Descriptor consolidation: Cytotoxicity profiles across cell lines and assays are consolidated into biological descriptors for read-across [4].

Read-Across Implementation Workflow

The implementation of integrative read-across follows a systematic workflow that can be visualized as follows:

Successful implementation of integrative read-across requires access to specialized computational tools, data resources, and experimental systems. The following table summarizes key resources that form the essential toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Integrative Read-Across

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Key Functionality | Application in Read-Across |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure Tools | Dragon Software [4] | Calculation of chemical descriptors | Structural representation and similarity assessment |

| RDKit [8] | Open-source cheminformatics | Chemical fingerprint generation and manipulation | |

| Biological Data Resources | ToxCast/Tox21 [5] [7] | High-throughput screening data | Source of bioactivity descriptors for mechanism inference |

| TG-GATES [4] [8] | Toxicogenomics database | Gene expression profiles for hepatotoxicity prediction | |

| DrugMatrix [4] | Toxicogenomics resource | Gene expression data for hepatocarcinogenicity assessment | |

| Similarity Assessment Tools | OECD QSAR Toolbox [4] [5] | Read-across and category formation | Structural analogue identification and data gap filling |

| ToxMatch [5] | Similarity profiling | Alternative similarity metrics and neighbor identification | |

| Data Analysis Environments | R/Python with specialized packages [8] | Statistical analysis and modeling | Implementation of similarity calculations and prediction models |

| Reference Databases | CCRIS [4] | Chemical Carcinogenesis Research Information System | Mutagenicity reference data for model training and validation |

| CPDB [4] | Carcinogenicity Potency Database | Hepatocarcinogenicity reference data |

The evolution from traditional to integrative read-across approaches represents a significant advancement in chemical safety assessment methodology. The integration of chemical structural information with biological activity data has consistently demonstrated improved prediction accuracy across multiple toxicity endpoints while addressing key limitations of traditional structure-based approaches [4] [5] [6]. The quantitative performance assessments summarized in this article provide compelling evidence for the value of incorporating bioactivity data to reduce prediction uncertainty and enhance mechanistic interpretability.

The regulatory acceptance of read-across stands to benefit substantially from these methodological advances [5]. Integrative approaches address several key challenges that have hindered confidence in traditional read-across, including the subjective nature of analogue selection, limited mechanistic basis for predictions, and inadequate characterization of uncertainty. By providing a more transparent, objective, and biologically grounded framework for data gap filling, integrative read-across can support more reliable chemical safety decisions while reducing animal testing requirements.

Future developments in integrative read-across will likely focus on several key areas. First, the incorporation of adverse outcome pathway frameworks will strengthen the mechanistic basis for biological similarity assessments, enabling more targeted selection of bioactivity descriptors relevant to specific toxicity endpoints [5]. Second, advances in high-content screening and transcriptomics technologies will expand the breadth and depth of biological data available for integration, capturing more complex biological responses and pathway perturbations. Finally, standardized performance benchmarking frameworks and best practice guidelines will be essential for establishing confidence in these methods and promoting their consistent application in regulatory contexts [5] [8].

As chemical safety assessment continues to evolve toward more mechanistic and human-relevant approaches, integrative read-across methodologies will play an increasingly important role in bridging between traditional toxicology and emerging paradigms based on pathway-based risk assessment. The continued refinement and validation of these approaches will be essential for addressing the growing need for efficient and reliable chemical safety evaluation in both regulatory and product development contexts.

Source vs. Target Substances and Analogue vs. Category Approaches

Read-across is a fundamental methodology in chemical risk assessment used to predict the properties of a data-poor substance by leveraging existing data from similar, data-rich substances [9]. This approach is grounded in the principle that structurally similar substances are likely to have comparable physicochemical properties, environmental fate, and toxicological effects [10]. Under regulatory frameworks like the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) in the United States and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in the EU, read-across serves as a critical alternative to animal testing for filling data gaps, thereby streamlining the safety evaluation of new chemicals [11] [9]. This guide details the core concepts of source and target substances and the two primary grouping approaches, providing a structured comparison for professionals in chemical safety research.

Defining Key Concepts: Source and Target Substances

Target Substance

The target substance is the chemical entity under assessment for which specific property or toxicity data is lacking [11] [10]. This is the data-poor chemical that requires evaluation before it can enter the marketplace or be approved for use.

Source Substance

The source substance (or source analogue) is a chemically similar compound for which the necessary experimental data on the relevant properties or endpoints is already available [9] [12]. Data from the source substance is used to make predictions about the target substance.

Table 1: Core Definitions in Read-Across

| Term | Definition | Role in Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Target Substance | The data-poor chemical being assessed [10]. | The subject of the safety evaluation; its unknown properties need to be predicted. |

| Source Substance | The data-rich, structurally similar chemical used for comparison [9]. | Provides the experimental data to fill the data gaps for the target substance. |

Comparative Analysis of Read-Across Grouping Approaches

The two main methodological frameworks for grouping chemicals in read-across are the analogue approach and the category approach. The choice between them depends on the number of suitable source substances available and the desired robustness of the prediction.

Analogue Approach

The analogue approach involves a direct, one-to-one comparison between a target substance and a single source substance that is considered to be its closest match [11] [9]. This method is typically chosen when one particularly strong analogue is available. It relies on a high degree of structural and mechanistic similarity to justify the direct extrapolation of data from the source to the target [10].

Category Approach

The category approach is a more robust method that involves grouping the target substance with at least two or more source substances that form a chemically similar category [11] [9]. This approach allows for the identification of trends or patterns in the data across the category. Predictions for the target substance can then be made through interpolation or extrapolation within these established trends, which can lead to more reliable and nuanced estimates than a single analogue [10].

Table 2: Analogue Approach vs. Category Approach

| Feature | Analogue Approach | Category Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Direct comparison of a target with a single source chemical [9]. | Grouping of a target with multiple source chemicals [11]. |

| Basis for Grouping | High degree of structural and mechanistic similarity [10]. | Common functional group, incremental change (e.g., carbon chain length), or common mode of action [11] [10]. |

| Prediction Method | Direct extrapolation of data from source to target [9]. | Interpolation, extrapolation, or trend analysis within the category [11]. |

| Data Robustness | Relies on the strength of a single analogue; can be less robust. | Leverages multiple data points; generally considered more robust and reliable [10]. |

| Best Use Case | When one exceptionally well-matched source analogue is available. | When several similar chemicals exist, allowing for trend analysis and a stronger weight of evidence. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process and steps involved in selecting and applying these two approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Read-Across Assessment

Executing a scientifically valid read-across assessment requires a structured workflow. The following protocols, synthesized from regulatory guidance, ensure a systematic and transparent process [9] [10].

Problem Formulation and Target Characterization

- Objective: Clearly define the data gap and the specific property or toxicological endpoint that needs to be predicted.

- Protocol: Compile all available information on the target substance, including its chemical structure, known physicochemical properties (e.g., log P, water solubility, vapor pressure), and any existing toxicological or fate data [10]. This profile is the baseline for identifying similarity.

Source Substance Identification and Evaluation

- Objective: Identify and justify the selection of source substance(s).

- Protocol:

- Search: Use chemical databases (e.g., EPA's CompTox Chemicals Dashboard) to search for potential source substances based on structural similarity [12] [10].

- Compare Structures: Analyze molecular weights, common functional groups, and key structural fragments [10].

- Compare Properties: Evaluate similarity in physicochemical properties that influence fate and bioavailability [10].

- Compare Mechanistic Data: If available, compare metabolism pathways, degradation products, and in vitro bioactivity data to support a similar biological mechanism of action [9] [10].

Data Gap Filling and Uncertainty Assessment

- Objective: Fill the data gap and evaluate the confidence in the prediction.

- Protocol:

- For the Analogue Approach, directly transpose the experimental value from the source substance to the target, or apply a simple scaling factor if justified [10].

- For the Category Approach, use trend analysis or quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models to interpolate or extrapolate a value for the target substance based on its position within the category [11].

- Uncertainty Assessment: Systematically document all uncertainties, including the degree of structural similarity, differences in potency, and any data quality concerns. Use New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) like in vitro assays or computational models to reduce key uncertainties [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following tools and databases are critical for conducting a robust read-across assessment.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Read-Across

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Read-Across |

|---|---|---|

| EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | Database | Provides access to a wealth of physicochemical, toxicity, and bioassay data for thousands of chemicals to identify and characterize source substances [12]. |

| Generalized Read-Across (GenRA) | Software Tool | An algorithmic, web-based application within the CompTox Dashboard that helps identify candidate analogues and make objective predictions of in vivo toxicity based on structural and bioactivity similarity [12]. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Software Tool | A comprehensive tool to profile chemicals, identify structural analogues and metabolic pathways, and fill data gaps by grouping chemicals into categories [9]. |

| EPI Suite | Software Tool | A suite of physicochemical property and environmental fate estimators used to predict key properties for the target and source substances when experimental data is missing [11]. |

| New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) | Experimental Methods | A suite of non-animal methods (e.g., in vitro assays, high-throughput screening, omics technologies) used to generate mechanistic data that supports the biological similarity between source and target substances [9]. |

| Isopsoralenoside | Isopsoralenoside, MF:C17H18O9, MW:366.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Olomoucine Ii | Olomoucine Ii, CAS:500735-47-7, MF:C19H26N6O2, MW:370.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Read-across is a fundamental methodology in chemical risk assessment used to predict the toxicological properties of a target substance with limited data by using information from structurally and mechanistically similar source substances [2]. This approach operates on the principle that structurally similar compounds exhibit similar biological effects, making it a reliable tool for prediction when experimental data is scarce [13]. As regulatory bodies worldwide increasingly aim to reduce animal testing, read-across has become an essential component of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) for filling critical data gaps while maintaining human health protection standards [14]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has developed comprehensive guidance for using read-across in food and feed risk assessment, providing a step-by-step framework for problem formulation, substance characterization, uncertainty analysis, and conclusion reporting [2].

The scientific foundation of read-across rests on three interconnected pillars: structural similarity, which establishes the fundamental comparability between chemicals; toxicokinetics (what the body does to a chemical), which describes absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion; and toxicodynamics (what the chemical does to the body), which encompasses the biological interactions and effects at target sites [14]. Understanding these interrelated components allows researchers to make more accurate predictions about chemical safety, supporting the transition toward innovative, human-relevant risk assessment strategies that reduce reliance on traditional animal testing [15] [14]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental approaches and computational methodologies that form the scientific basis for modern read-across applications in chemical safety research.

Structural Similarity Assessment: Methods and Comparative Performance

Structural similarity assessment forms the foundational basis for read-across, predicated on the principle that compounds with analogous molecular structures are likely to exhibit comparable biological activities and toxicological profiles [13]. Multiple computational approaches have been developed to quantify and evaluate structural similarity, each with distinct methodologies, strengths, and limitations. The accurate assessment of structural similarity is crucial for establishing valid read-across hypotheses and ensuring reliable toxicity predictions.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Structural Similarity Assessment Methods

| Method Category | Specific Approach | Key Metrics/Descriptors | Reported Performance | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatic Fingerprints | Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP), Atom Pair (AP), Pharmacophore Fingerprint (PHFP) [16] | Binary structural features, topological atom environments, pharmacophoric points | Varies by fingerprint type; Multi-representation fusion improves recall-precision balance [16] | Initial similarity screening, chemical space characterization |

| Multi-Representation Data Fusion | AgreementPred framework combining 22 molecular representations [16] | Combined similarity scores from multiple fingerprints, agreement scores | Recall: 0.74, Precision: 0.55 (agreement score threshold: 0.1) [16] | Drug and natural product category recommendation |

| Quantitative Read-Across Structure-Activity Relationship (q-RASAR) | Integration of QSAR descriptors with read-across predictions [13] | 0D-2D molecular descriptors, similarity-based predictions | Enhanced predictive accuracy vs. QSAR alone; Reduced mean absolute error (MAE) [13] | Predicting human toxicity endpoints (e.g., TDLo) |

| Explainable AI Integration | SHAP analysis with machine learning models [13] | Feature importance values, mechanistic interpretability | Improved model transparency and mechanistic insights [13] | Identifying key structural features linked to toxicity |

Recent advancements in structural similarity assessment have focused on multi-representation approaches and hybrid methodologies. The AgreementPred framework demonstrates that combining similarity search results from multiple molecular representations significantly improves the recall-precision balance in category recommendation tasks compared to single-representation methods [16]. Similarly, the development of q-RASAR models represents a substantive advancement by integrating traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) descriptors with similarity-based read-across predictions, resulting in enhanced predictive accuracy for human toxicity endpoints such as the toxic dose low (TDLo) [13]. These hybrid approaches effectively address the limitation of conventional read-across, which often struggles with interpreting key structural features responsible for observed toxicological effects.

Experimental Protocol: Structural Similarity Workflow

A standardized workflow for structural similarity assessment in read-across applications typically involves several key stages. First, target substance characterization entails compiling comprehensive molecular information, including chemical structure, functional groups, and physicochemical properties. Subsequently, source substance identification involves searching chemical databases for structurally analogous compounds using multiple fingerprint methods and similarity metrics (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient). The third phase encompasses similarity validation, which assesses not only structural similarity but also mechanistic plausibility through biological pathway analysis. Finally, uncertainty quantification evaluates the confidence in similarity hypotheses using quantitative measures and potential adjustments through additional data from New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) [2] [13].

Figure 1: Structural similarity assessment workflow for read-across.

Toxicokinetics in Read-Across: Comparative Methodologies

Toxicokinetics (TK) describes the time course of chemical absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) within biological systems. In read-across applications, comparing the TK profiles of source and target substances provides critical insights into their internal dosimetry and potential biological effects. Significant advances in computational toxicokinetics have enabled more reliable extrapolations between structurally similar compounds, enhancing the predictive capability of read-across for human health risk assessment.

Table 2: Comparison of Toxicokinetic Modeling Approaches for Read-Across

| Methodology | Technical Approach | Data Requirements | Regulatory Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling [14] | Mathematical representation of ADME processes in physiological compartments | Chemical-specific parameters, in vitro metabolism data, physiological constants | Risk translation, exposure reconstruction, chemical-chemical interactions [14] | Species extrapolation, route-to-route extrapolation, quantitative dose-response prediction |

| High-Throughput TK (HTTK) Models [14] | High-throughput in vitro data integration with simplified TK models | High-throughput in vitro clearance data, chemical properties | Chemical prioritization and screening, initial TK parameter estimation [14] | Rapid screening of large chemical libraries, cost-effective initial assessment |

| Toxicogenomics Integration [14] | OMICS data analysis for metabolic pathway identification | Transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic data | Mechanism identification, point of departure (PoD) calculation [14] | Comprehensive pathway analysis, identification of susceptible populations |

| In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) [14] | Mathematical extrapolation from in vitro systems to in vivo responses | In vitro bioactivity data, protein binding, metabolic stability | Benchmark dose modeling, risk assessment [14] | Reduction of animal testing, human-relevant data generation |

The integration of toxicokinetic data into read-across assessments significantly strengthens the scientific basis for extrapolations between source and target substances. For instance, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recently utilized a PBPK model to establish a tolerable weekly intake (TWI) for four per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) based on immunotoxicity endpoints [14]. This application demonstrates how TK modeling can support quantitative risk assessment for chemical groups within a read-across framework. Similarly, high-throughput toxicokinetic tools such as httk and TK-plate are gaining prominence in chemical screening and prioritization, enabling more efficient evaluation of structurally related compounds [14].

Experimental Protocol: Toxicokinetic Data Generation

The generation of toxicokinetic data for read-across applications typically follows a tiered approach. Initial screening employs high-throughput in vitro methods to assess fundamental ADME properties, including metabolic stability in liver microsomes or hepatocytes, cellular permeability in Caco-2 or MDCK models, and plasma protein binding [14]. For higher-tier assessments, more comprehensive investigations utilize advanced tissue models such as 3D spheroids, organoids, or microphysiological systems (MPS) that better recapitulate in vivo tissue complexity and metabolic capacity [14]. The resulting data are subsequently integrated into PBPK models for in vitro-to-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE), enabling prediction of human exposure scenarios and internal tissue doses [14]. This integrated approach facilitates direct comparison of TK behaviors between source and target substances, strengthening the scientific basis for read-across conclusions.

Figure 2: Toxicokinetic data generation workflow for read-across.

Toxicodynamics: Mechanism-Based Read-Across

Toxicodynamics encompasses the biochemical and physiological effects of chemicals on biological systems, including the molecular interactions and subsequent cascades of events leading to adverse outcomes. Mechanism-based read-across represents a significant advancement beyond structural similarity alone, as it focuses on establishing common modes of action between source and target substances. The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework has emerged as a particularly valuable tool for organizing toxicodynamic knowledge and supporting mechanistic read-across predictions [14].

The AOP framework provides a structured representation of biologically plausible sequences of events spanning multiple levels of biological organization, from molecular initiating events to cellular, organ, and organism-level responses [14]. By mapping both source and target substances onto relevant AOPs, researchers can establish mechanistic similarity even in cases where structural similarity is moderate. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing complex toxicity endpoints where multiple structural classes may converge on common biological pathways. Computational toxicology tools such as molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and systems biology models contribute significantly to characterizing molecular initiating events and key intermediate steps in AOPs [14].

Experimental Protocol: Toxicodynamic Characterization

Comprehensive toxicodynamic characterization for read-across applications typically employs a combination of in vitro and in silico approaches. Initial assessment involves identifying molecular initiating events through target-based assays, such as receptor binding studies or enzyme inhibition assays [14]. For nuclear receptors, which represent important targets for many endocrine-active chemicals, structural characterization using both experimental methods (X-ray crystallography) and computational approaches (AlphaFold 2 predictions) can provide insights into ligand-receptor interactions [17]. Subsequent evaluation of key events along relevant AOPs utilizes specialized in vitro models, including high-content screening in cell cultures, 3D tissue models, and transcriptomic or proteomic analyses [14]. Integration of these data points within the AOP framework enables a weight-of-evidence assessment of mechanistic similarity between source and target substances, substantially strengthening the scientific basis for read-across.

Figure 3: Toxicodynamic characterization workflow for read-across.

Integrated Approach: Combining Structural Similarity, TK, and TD

The most robust read-across assessments integrate all three scientific pillars—structural similarity, toxicokinetics, and toxicodynamics—within a cohesive framework. This integrated approach aligns with the Integrated Approaches for Testing and Assessment (IATA) advocated by regulatory agencies such as the OECD [14]. By combining evidence from multiple sources, researchers can develop a comprehensive weight-of-evidence that substantially reduces uncertainty in read-across predictions.

The ASPIS cluster, comprising three major EU projects (ONTOX, PrecisionTox, and RISK-HUNT3R), exemplifies this integrated strategy with a collective investment of €60 million aimed at revolutionizing chemical safety assessment [15]. ONTOX develops innovative NAMs for predicting systemic repeated-dose toxicity effects by integrating AI-driven computational approaches with biological, toxicological, and kinetic data [15]. PrecisionTox employs a comparative toxicogenomics approach across multiple species to identify conserved molecular toxicity pathways and understand susceptibility variations within human populations [15]. RISK-HUNT3R focuses on implementing integrated, human-centric risk assessment tools using in vitro and in silico NAMs to evaluate chemical exposure, toxicokinetics, and toxicodynamics [15]. Together, these initiatives represent the cutting edge of mechanism-based read-across that transcends traditional structural similarity approaches.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Read-Across Approaches

| Approach | Structural Basis | TK Consideration | TD Consideration | Uncertainty Management | Regulatory Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Structural Read-Across [18] | Primary focus | Limited | Limited | Qualitative assessment | Mixed success; often challenged [18] |

| q-RASAR Approach [13] | Quantitative | Indirect via descriptors | Indirect via endpoints | Statistical confidence measures | Emerging, with promising applications |

| Mechanism-Based Read-Across [14] | Foundation | Integrated TK modeling | AOP-informed | Weight-of-evidence framework | Growing acceptance for specific endpoints |

| Integrated TK/TD Approach [15] [14] | Comprehensive | PBPK modeling | AOP network analysis | Quantitative uncertainty analysis | High potential, currently developing |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Read-Across Applications

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application in Read-Across |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | TOXRIC, DrugBank, LOTUS, NPASS, HERB2.0 [13] [16] | Source of chemical structures, annotations, and toxicity data | Provides curated data for source and target substances |

| Cheminformatics Tools | KNIME Cheminformatics Extensions, OECD QSAR Toolbox [13] [14] | Molecular descriptor calculation, structural similarity assessment | Enables quantitative similarity assessment and descriptor generation |

| Toxicogenomics Platforms | ToxCast, comparative toxicogenomics databases [14] | Bioactivity screening, mechanistic data generation | Supports AOP development and mechanistic similarity assessment |

| TK Modeling Platforms | httk, TK-plate, PBPK modeling software [14] | TK parameter estimation, IVIVE, dose-response prediction | Facilitates TK similarity assessment and internal dose estimation |

| Structural Biology Tools | AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, RCSB PDB [17] | Protein-ligand interaction analysis, binding pocket characterization | Enables assessment of molecular initiating events |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Random Forest, SVM, SHAP analysis [13] | Pattern recognition, toxicity prediction, model interpretability | Enhances prediction accuracy and provides mechanistic insights |

| Retaspimycin | Retaspimycin, CAS:857402-23-4, MF:C31H45N3O8, MW:587.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dihydroartemisinic acid | Dihydroartemisinic acid, CAS:85031-59-0, MF:C15H24O2, MW:236.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The implementation of robust read-across requires specialized computational tools and databases. The OECD QSAR Toolbox represents a particularly valuable resource that integrates multiple NAMs approaches, including in vitro data, OMICS, PBPK, and QSAR, to build weight of evidence for different chemicals and endpoints [14]. For structural similarity assessment, the AgreementPred framework demonstrates how combining multiple molecular representations (22 in its implementation) can improve the recall-precision balance in category recommendation tasks [16]. For toxicokinetic modeling, open-source tools such as httk provide high-throughput toxicokinetic parameters for chemical prioritization and initial risk assessment [14]. These tools, when used in combination, create a comprehensive ecosystem for implementing scientifically rigorous read-across that addresses all three key scientific pillars.

Read-across is a sophisticated method used in chemical risk assessment to predict the toxicological properties of a target substance by using experimental data from structurally and mechanistically similar substances, known as source substances [2]. This approach has gained significant traction within global regulatory frameworks as a New Approach Methodology (NAM) that can potentially reduce reliance on traditional animal testing while maintaining rigorous safety standards. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the nuanced acceptance patterns of read-across across different regulatory agencies is critical for successful chemical safety evaluation and regulatory submission.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has developed a systematic framework for applying read-across in food and feed safety assessment, emphasizing a weight-of-evidence evaluation for individual substances [2]. This framework provides a step-by-step workflow encompassing problem formulation, target substance characterization, source substance identification, source substance evaluation, data gap filling, uncertainty assessment, and conclusion reporting. The ultimate goal is to equip risk assessors and applicants with a comprehensive methodology to carry out read-across assessments systematically and transparently, thereby supporting the safety evaluation of chemicals throughout the food and feed chain.

Global Regulatory Acceptance of New Approach Methodologies

Comparative Analysis of Agency Acceptance

Regulatory agencies worldwide have increasingly accepted specific alternative methods and defined approaches that align with the read-across paradigm. The table below summarizes the acceptance of selected methodologies across major international agencies:

Table 1: Regulatory Acceptance of Selected Alternative Methods and Defined Approaches

| Toxicity Area | Method/Approach | U.S. Acceptance | EU Acceptance | Applicable Regulations/Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin Sensitization | Defined approaches on skin sensitization | Accepted [19] | Accepted [19] | OECD Guideline 497 (2021, updated 2025) |

| Ocular Irritation/Corrosion | Defined approaches for serious eye damage and eye irritation | Accepted [19] | Accepted [19] | OECD Test Guideline 467 (2022, updated 2025) |

| Endocrine Disruption | Rapid androgen disruption activity reporter assay | Accepted [19] | Accepted [19] | OECD Test Guideline 251 (2022) |

| Developmental Neurotoxicity | Evaluation of data from developmental neurotoxicity testing battery | Accepted [19] | Accepted [19] | OECD Guidance Document 377 (2023) |

| Ecotoxicity | Fish cell line acute toxicity - RTgill-W1 cell line assay | Accepted [19] | Accepted [19] | OECD Test Guideline 249 (2021) |

| Immunotoxicity | In vitro immunotoxicity: IL-2 Luc assay | Accepted [19] | Accepted [19] | OECD Test Guideline 444A (2023, updated 2025) |

Regional Implementation Patterns

While harmonization through OECD test guidelines is evident, implementation varies by region and regulatory context. The U.S. EPA, FDA, and CPSC have issued agency-specific guidance documents that incorporate these methodologies into their chemical assessment frameworks [19]. Similarly, the European Union has established extensive protocols through EFSA for implementing read-across within food and feed safety assessment [2]. The year 2025 represents a significant milestone in regulatory evolution, with international agencies accelerating implementation of stricter rules that redefine global standards, particularly in sustainability, AI governance, and data privacy [20].

A notable trend across regulatory agencies is the emphasis on transparency and data quality in read-across submissions. EFSA's guidance specifically highlights the importance of clarity, impartiality, and quality to derive transparent and reliable read-across conclusions [2]. The analysis of uncertainty and strategies to reduce it to tolerable levels through standardized approaches and/or additional data from NAMs represents a critical component of regulatory acceptance across all major agencies.

Methodological Framework for Read-Across Assessment

EFSA Read-Across Workflow Methodology

The EFSA read-across framework provides a systematic methodology for chemical safety assessment that can be adapted across regulatory contexts. The workflow consists of sequential phases:

Table 2: Key Phases in Read-Across Assessment Methodology

| Phase | Key Activities | Methodological Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Formulation | Define assessment scope, data requirements, and chemical categories | Establish assessment goals and identify knowledge gaps |

| Target Substance Characterization | Comprehensive characterization of physicochemical properties, structural features, and metabolic pathways | Identify potential metabolites and impurities; determine adequacy of existing data |

| Source Substance Identification | Identify structurally and mechanistically similar substances | Establish similarity justification based on structural, metabolic, and mechanistic criteria |

| Source Substance Evaluation | Evaluate quality and adequacy of source substance data | Assess data reliability, relevance, and completeness for endpoint prediction |

| Data Gap Filling | Use source substance data to predict target substance properties | Justify applicability of data for specific endpoints; address uncertainties |

| Uncertainty Assessment | Evaluate and characterize uncertainties in read-across prediction | Identify sources of uncertainty and strategies for reduction |

| Conclusion and Reporting | Document rationale, evidence, and conclusions | Ensure transparency and reproducibility of assessment |

Experimental Protocols for Read-Across Justification

Successful read-across applications require robust experimental protocols to substantiate the similarity hypothesis between source and target substances. Key methodological considerations include:

Structural Similarity Assessment: Computational approaches including QSAR models, molecular fingerprinting, and functional group analysis establish structural similarity between source and target substances. The assessment must demonstrate that differences in structure do not significantly impact toxicological properties for the endpoints being assessed.

Metabolic Pathway Characterization: Comparative metabolism studies using in vitro systems such as hepatocytes or microsomal preparations identify similar metabolites and metabolic pathways between source and target substances. Discrepancies in metabolism may necessitate additional data or invalidate the read-across hypothesis.

Mechanistic Profiling: Mechanistic similarity is established through in vitro bioactivity profiling across multiple pathways relevant to the target endpoint. High-throughput screening assays and omics technologies provide mechanistic evidence supporting the similarity hypothesis.

Toxicokinetic Considerations: Comparative assessment of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties ensures similar internal exposure patterns between source and target substances. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling may be employed to extrapolate internal doses across substances.

The methodological workflow for read-across assessment can be visualized as follows:

Read-Across Assessment Workflow

Comparative Assessment Tools for Chemical Alternatives

Standardized Methodologies for Alternative Assessment

When applying read-across to evaluate chemical alternatives, several standardized tools facilitate systematic comparison of health, environmental, and physical hazards. These methodologies enable researchers to make informed decisions about safer substitutions:

Table 3: Standardized Tools for Chemical Alternative Assessment

| Assessment Tool | Developer | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Column Model | German Federation of Institutions for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention (IFA) | Six hazard categories divided into risk levels from negligible to very high; uses GHS classifications | Small and medium-sized businesses assessing substitute substances with limited information [21] |

| Quick Chemical Assessment Tool (QCAT) | Washington Department of Ecology | Nine high-priority hazard endpoints; grades chemicals A-F along a continuum of concern | Rapid identification of chemicals equally or more toxic than the chemical being assessed [21] |

| Pollution Prevention Options Analysis System (P2OASys) | Massachusetts Toxics Use Reduction Institute | Scores chemicals based on quantitative and qualitative data for multiple hazard types; indicates very low to very high risk | Determining potential negative impacts of alternatives on workers, public health, or environment [21] |

| Green Screen for Safer Chemicals | Clean Production Action | Comprehensive hazard assessment using authoritative and screening data sources; identifies preferred chemicals | Benchmarking chemicals against specific hazard criteria to identify safer alternatives [21] |

Hazard Endpoints for Comparative Assessment

A comprehensive read-across assessment for chemical alternatives requires evaluation across multiple hazard domains, including:

Acute Health Hazards: Acute toxicity, eye damage, skin damage, and sensitization (skin, respiratory) represent critical endpoints for comparative assessment [21]. These endpoints are particularly relevant for worker safety evaluation during chemical handling and use.

Chronic Health Hazards: Chronic toxicity, target organ toxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity/genotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, developmental toxicity, endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity, and immune system effects require careful evaluation in alternatives assessment [21].

Physical and Environmental Hazards: Flammability, reactivity, explosivity, corrosivity, oxidizing properties, and pyrophoric properties must be considered alongside environmental fate and ecotoxicity endpoints [21].

The relationship between assessment components and hazard considerations can be visualized as:

Chemical Alternative Assessment Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Successful implementation of read-across approaches requires specific methodological tools and resources. The following table details essential components of the regulatory scientist's toolkit for read-across applications:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Read-Across Applications

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Grouping of chemicals into categories and filling data gaps | Systematic identification of structurally similar compounds and metabolic pathways |

| EPA's CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | Access to chemistry, toxicity, and exposure data for thousands of chemicals | Preliminary assessment of chemical similarities and data availability |

| VEGA (Virtual Engine for Geo- chemical Assessment) | Platform integrating QSAR models for toxicity prediction | Hazard assessment for multiple endpoints when experimental data are limited |

| OECD Test Guidelines | Standardized methodologies for specific toxicity endpoints | Generation of reliable data for read-across justification [19] |

| ToxTrack & High-Throughput Screening | Mechanistic bioactivity profiling across multiple pathways | Establishing mechanistic similarity between source and target substances |

| Toxicogenomics Platforms | Gene expression profiling for mode-of-action analysis | Understanding mechanistic similarities at molecular level |

| In Vitro ADME Systems | Hepatocytes, microsomes, permeability assays | Comparative assessment of metabolic fate and toxicokinetics |

| Chemotyping Approaches | Structural alert identification and categorization | Grouping chemicals based on reactive moieties and potential mechanisms |

| Indinavir sulfate ethanolate | Indinavir sulfate ethanolate, MF:C38H55N5O9S, MW:757.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cladosporide A | Cladosporide A | Cladosporide A is a natural antifungal agent for research use only (RUO). It inhibits pathogenic fungi like A. fumigatus. Explore its applications. |

The global regulatory landscape for chemical safety assessment demonstrates increasing convergence in the acceptance of read-across and New Approach Methodologies. The harmonization through OECD test guidelines and guidance documents provides a foundation for global alignment, while region-specific implementation frameworks reflect local regulatory priorities and historical contexts [19].

For researchers and drug development professionals, success in regulatory submission requires robust methodological execution of read-across assessments, with particular emphasis on transparent documentation of the similarity hypothesis, comprehensive uncertainty analysis, and integration of appropriate NAMs to strengthen the weight of evidence. The ongoing development of resources such as the Collection of Alternative Methods for Regulatory Application (CAMERA), with its planned public Beta release in Q3 2025, promises to further streamline regulatory acceptance of these approaches [19].

As international regulatory cooperation intensifies, particularly in response to emerging challenges in sustainability, AI governance, and chemical management, the read-across approach is positioned to play an increasingly central role in efficient, human-relevant chemical safety assessment across global markets.

Implementing Read-Across: Methodological Frameworks and Practical Applications

In chemical safety assessment, read-across has emerged as a primary method for filling data gaps by predicting the toxicological properties of a data-poor target substance using information from structurally and mechanistically similar, data-rich source substances [9]. This guide compares the performance of traditional and advanced read-across methodologies, providing researchers with a clear framework for implementation.

Experimental Comparison of Read-Across Methodologies

A comparative study evaluated traditional chemical-based read-across against a hybrid chemical-biological method using two large toxicity datasets: Ames mutagenicity (3,979 compounds) and rat acute oral toxicity (7,332 compounds) [22]. The experimental design is summarized below.

Table 1: Experimental Parameters and Performance Metrics

| Parameter | Ames Mutagenicity Dataset | Rat Acute Oral Toxicity Dataset |

|---|---|---|

| Total Compounds | 3,979 | 7,332 |

| Toxic Compounds | 1,718 | Quantitative LD50 values |

| Non-Toxic Compounds | 2,261 | Quantitative LD50 values |

| Chemical Descriptors | 192 standardized 2-D MOE descriptors [22] | 192 standardized 2-D MOE descriptors [22] |

| Biological Profiles (Bioprofiles) | PubChem bioassays; biosimilarity calculated via CIIPro portal [22] | PubChem bioassays; biosimilarity calculated via CIIPro portal [22] |

| Prediction Method | Nearest neighbor in training set [22] | Nearest neighbor in training set [22] |

Table 2: Predictive Performance Results

| Methodology | Dataset | Sensitivity | Specificity | CCR (Balanced Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Read-Across (Chemical Similarity Only) | Ames Mutagenicity | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.76 |

| Hybrid Read-Across (Chemical + Biological Similarity) | Ames Mutagenicity | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| Traditional Read-Across (Chemical Similarity Only) | Acute Oral Toxicity | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.70 |

| Hybrid Read-Across (Chemical + Biological Similarity) | Acute Oral Toxicity | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.77 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Traditional Read-Across

- Chemical Similarity Calculation: For each compound, 192 2-D chemical descriptors were generated using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software. Descriptors were standardized and rescaled (0-1 range). Pairwise chemical similarity ((S{chem})) was calculated based on the Euclidean distance ((d{Euc})) between the 192-dimensional vectors of two compounds [22].

- Read-Across Prediction: The prediction for a target compound was made by directly using the toxicity value of its nearest neighbor in the training set, identified solely through chemical similarity search [22].

Protocol for Hybrid Chemical-Biological Read-Across

- Biosimilarity Calculation: Biological data for all compounds were obtained from the PubChem database via the CIIPro portal. The biosimilarity ((S_{bio})) between two compounds was calculated using a weighted equation that considers their active and inactive responses in the same set of bioassays, giving more weight to active data [22].

- Hybrid Prediction: The prediction for a target compound was made by first identifying its chemical nearest neighbor. Subsequently, the biosimilarity between the target and this chemical neighbor was calculated. The final prediction was made by the toxicity value of this confirmed chemical-biological nearest neighbor [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Read-Across

| Item | Function in Read-Across Assessment |

|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) Software | Generates essential 2-D chemical descriptors for calculating structural similarity between compounds [22]. |

| PubChem Database | Provides public repository of biological assay data used to generate bioactivity profiles (bioprofiles) for biosimilarity assessments [22]. |

| CIIPro (Chemical In Vitro-In Vivo Profiling) Portal | A specialized tool for obtaining and processing PubChem bioassay data to calculate biosimilarity metrics [22]. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Software that facilitates the systematic grouping of chemicals into categories using chemical similarity read-across and trend analysis [9] [22]. |

| ToxMatch | An open-source software application that encodes chemical similarity calculation tools to support the development of chemical groupings and read-across [22]. |

| Hongoquercin B | Hongoquercin B: Antibacterial Research Compound |

| Glucodichotomine B | Glucodichotomine B, MF:C20H22N2O9, MW:434.4 g/mol |

The Standardized Read-Across Workflow

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has developed a structured workflow to standardize the read-across process, ensuring transparency and reliability in chemical safety assessments [9]. This workflow is visualized below.

Read-Across Workflow Steps

- Problem Formulation: Define the scope and data gaps to be addressed [9].

- Target Substance Characterisation: Gather all available data on the substance being assessed [9].

- Source Substance Identification: Identify structurally and mechanistically similar substances with adequate data [9].

- Source Substance Evaluation: Critically assess the quality and relevance of data from source substances [9].

- Data Gap Filling: Perform the read-across prediction to fill the identified data gaps [9].

- Uncertainty Assessment: Evaluate all sources of uncertainty in the assessment [9].

- Conclusion & Reporting: Draw conclusions and document the process transparently [9].

Key Methodological Relationships in Read-Across

The core of a successful read-across assessment lies in establishing a robust similarity justification between the source and target substances. This involves multiple, interconnected factors [9].

The hybrid read-across method demonstrates a statistically significant improvement in predictive performance over the traditional approach for complex toxicity endpoints. By integrating publicly available biological data with traditional chemical descriptors, the hybrid method partially resolves the "activity cliff" issue and offers a more robust, data-driven framework for chemical safety assessment [22]. The standardized EFSA workflow provides a transparent, systematic structure for applying these methodologies, ensuring reliable and defensible read-across conclusions in regulatory contexts [9].