QSAR Validation: Best Practices, Modern Methods, and Regulatory Compliance for Predictive Modeling

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model validation, a critical pillar of computational drug discovery and chemical safety assessment.

QSAR Validation: Best Practices, Modern Methods, and Regulatory Compliance for Predictive Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model validation, a critical pillar of computational drug discovery and chemical safety assessment. Tailored for researchers and development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of QSAR, detail rigorous methodological workflows for model development and application, and address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. A core focus is placed on contemporary validation strategies and comparative metric analysis, equipping scientists with the knowledge to build, assess, and deploy robust, reliable, and regulatory-compliant QSAR models for virtual screening and lead optimization.

The Pillars of Trust: Foundational Principles of QSAR Validation

Defining QSAR and the Critical Role of Validation in Drug Discovery

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) is a computational modeling method that establishes mathematical relationships between the chemical structure of compounds and their biological activities or physicochemical properties [1] [2] [3]. The foundational principle of QSAR is that variations in molecular structure produce systematic changes in biological responses, allowing researchers to predict the activity of new compounds without synthesizing them [1] [4]. This approach has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, significantly reducing the need for extensive and costly laboratory experiments [5] [3].

The origins of QSAR trace back to the 19th century when Crum-Brown and Fraser first proposed that the physiological action of a substance is a function of its chemical composition [5] [2]. However, the modern QSAR era began in the 1960s with the pioneering work of Corwin Hansch, who developed the Hansch analysis method that quantified relationships using physicochemical parameters such as lipophilicity, electronic properties, and steric effects [6]. Over the subsequent decades, QSAR has evolved from using simple linear models with few descriptors to employing complex machine learning algorithms with thousands of chemical descriptors [6]. This evolution has transformed QSAR into a powerful predictive tool that guides lead optimization and serves as a screening tool to identify compounds with desired properties while eliminating those with unfavorable characteristics [3].

The Critical Importance of Validation in QSAR Modeling

Why Validation Matters

Validation represents the most critical phase in QSAR model development, serving as the definitive process for establishing the reliability and relevance of a model for its specific intended purpose [1] [7]. Without rigorous validation, QSAR predictions remain unverified hypotheses with limited practical application in drug discovery. The fundamental objective of validation is to ensure that models possess both robustness (performance stability on the training data) and predictive power (ability to accurately predict new, untested compounds) [1] [7] [8].

The consequences of using unvalidated QSAR models in drug discovery can be severe, leading to misguided synthesis efforts, wasted resources, and potential clinical failures. As noted in recent literature, "The success of any QSAR model depends on accuracy of the input data, selection of appropriate descriptors and statistical tools, and most importantly validation of the developed model" [1]. Proper validation provides medicinal chemists with the confidence to utilize computational predictions for decision-making in the drug development pipeline, where time and resource constraints demand high-priority choices on which compounds to synthesize and test [9].

Key Validation Methodologies

QSAR models undergo multiple validation protocols to establish their reliability, each serving a distinct purpose in the evaluation process.

Internal validation, also known as cross-validation, assesses model robustness by systematically excluding portions of the training data and evaluating how well the model predicts the omitted values [7] [2]. The most common approach is leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation, where each compound is left out once and predicted by the model built on the remaining compounds [2]. However, this method may overestimate predictive capability, and leave-many-out approaches with repeated double cross-validation are often recommended, especially with smaller sample sizes [7] [8].

External validation represents the gold standard for evaluating predictive ability, where the dataset is split into training and test sets [7] [8]. The model is developed exclusively on the training set and subsequently used to predict the completely independent test set compounds. This approach provides a more realistic assessment of how the model will perform on genuinely new chemical entities [1] [7].

Data randomization or Y-scrambling verifies the absence of chance correlations by randomly shuffling the response variable and demonstrating that the model performance significantly degrades compared to the original data [1]. This validation step ensures that the model captures genuine structure-activity relationships rather than artificial patterns in the dataset.

Table 1: Key QSAR Validation Methods and Their Characteristics

| Validation Type | Key Procedure | Primary Objective | Common Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | Leave-one-out or leave-many-out cross-validation | Assess model robustness and prevent overfitting | Q², R²cv |

| External Validation | Splitting data into training and test sets | Evaluate true predictive capability on new compounds | R²test, RMSEtest |

| Data Randomization | Y-scrambling with shuffled responses | Verify absence of chance correlations | Significant performance degradation |

| Applicability Domain | Defining chemical space of reliable predictions | Identify compounds for which predictions are valid | Leverage, distance-based methods |

Established Validation Criteria and Protocols

Statistical Parameters for Validation

Multiple statistical criteria have been established to evaluate QSAR model validity, with each providing insights into different aspects of predictive performance. A comprehensive analysis of 44 reported QSAR models revealed that relying solely on the coefficient of determination (r²) is insufficient to indicate model validity [7] [8]. The most widely adopted criteria include:

The Golbraikh and Tropsha criteria represent one of the most cited validation approaches, requiring: (1) r² > 0.6 for the correlation between experimental and predicted values; (2) slopes K and K' of regression lines through the origin between 0.85 and 1.15; and (3) the difference between r² and r₀² (coefficient of determination for regression through origin) divided by r² should be less than 0.1 [7] [8].

Roy's criteria introduced the rₘ² metric, calculated as rₘ² = r²(1 - √(r² - r₀²)), which has gained widespread adoption in QSAR studies [7] [8]. This metric simultaneously considers the correlation between observed and predicted values and the agreement between them through regression through origin.

The Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) has been suggested as a robust validation parameter, with CCC > 0.8 typically indicating a valid model [7] [8]. The CCC evaluates both precision and accuracy by measuring how far observations deviate from the line of perfect concordance.

Table 2: Established Statistical Criteria for QSAR Model Validation

| Validation Criteria | Key Parameters | Threshold Values | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golbraikh & Tropsha | r², K, K', r₀² | r² > 0.6, 0.85 < K < 1.15, (r² - r₀²)/r² < 0.1 | Predictive accuracy and slope consistency |

| Roy's rₘ² | rₘ² | Higher values indicate better models (no universal threshold) | Combined measure of correlation and agreement |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient | CCC | CCC > 0.8 for valid models | Agreement with line of perfect concordance |

| Roy's Practical Criteria | AAE, SD, training set range | AAE ≤ 0.1 × training set range, AAE + 3×SD ≤ 0.2 × training set range | Practical prediction errors relative to activity range |

Experimental Protocols for QSAR Validation

A standardized workflow for QSAR model development and validation ensures reliable and reproducible results. The following protocol outlines the essential steps:

Step 1: Data Collection and Curation Collect a sufficient number of compounds (typically >20) with comparable activity values obtained through standardized experimental protocols [5]. The dataset should encompass diverse chemical structures representative of the chemical space of interest. Data curation removes duplicates and resolves activity inconsistencies [4].

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation Compute theoretical molecular descriptors or physicochemical properties that quantitatively represent structural characteristics [1] [6]. These may include electronic, geometric, steric, or topological descriptors calculated using software such as Dragon, Alvadesc, or RDKit [10] [4].

Step 3: Dataset Division Split the dataset into training and test sets using rational methods such as random selection, sphere exclusion, or activity-based sorting [7] [5]. Typically, 70-80% of compounds are allocated to the training set for model development, while the remaining 20-30% form the test set for external validation [4].

Step 4: Model Construction Apply statistical or machine learning methods to establish mathematical relationships between descriptors and biological activity [5] [6]. Common approaches include Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [5] [4].

Step 5: Comprehensive Validation Implement the validation hierarchy including internal cross-validation, external validation with the test set, and data randomization [1] [7]. Calculate all relevant statistical parameters outlined in Section 3.1 to assess model validity.

Step 6: Applicability Domain Definition Establish the chemical space region where reliable predictions can be expected using methods such as leverage, distance-based approaches, or PCA analysis [1]. This step is crucial for identifying when models are applied outside their scope.

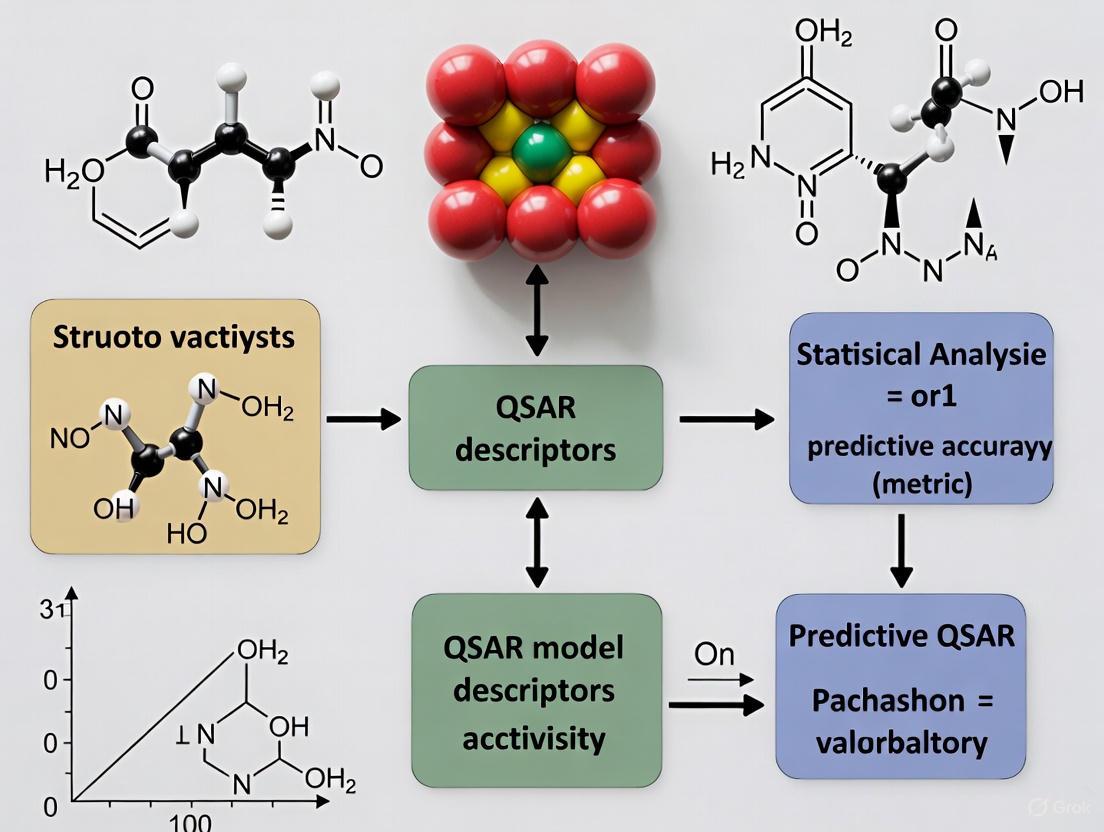

Diagram 1: QSAR Model Development and Validation Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the sequential process of building and validating QSAR models, with iterative refinement if validation criteria are not met.

Comparative Analysis of QSAR Validation Performance

Validation Benchmarking Across Multiple Studies

Comparative studies have provided valuable insights into the performance of different validation approaches. A comprehensive analysis of 44 QSAR models revealed significant variations in validation outcomes depending on the criteria applied [7] [8]. The findings demonstrated that models satisfying one set of validation criteria might fail others, highlighting the importance of multi-faceted validation strategies.

In a case study involving NF-κB inhibitors, researchers developed both Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models, with the ANN models demonstrating superior predictive capability upon rigorous validation [5]. The leverage method was employed to define the applicability domain, ensuring that predictions were only made for compounds within the appropriate chemical space [5].

Ensemble machine learning approaches have shown particular promise in QSAR modeling, with comprehensive ensemble methods consistently outperforming individual models across 19 bioassay datasets [4]. One study found that the comprehensive ensemble method achieved an average AUC (Area Under the Curve) of 0.814, followed by ECFP-Random Forest (0.798) and PubChem-Random Forest (0.794) [4]. This superior performance was attributed to the ensemble's ability to manage the strengths and weaknesses of individual learners, similar to how people consider diverse opinions when faced with critical decisions [4].

Paradigm Shifts in QSAR Validation for Virtual Screening

Traditional validation approaches emphasizing balanced accuracy are undergoing reconsideration for virtual screening applications. Recent research indicates that for virtual screening of ultra-large chemical libraries, models with the highest Positive Predictive Value (PPV)—trained on imbalanced datasets—outperform models optimized for balanced accuracy [9].

This paradigm shift stems from practical considerations in early drug discovery, where only a small fraction of virtually screened molecules can be experimentally tested. Studies demonstrate that training on imbalanced datasets achieves a hit rate at least 30% higher than using balanced datasets, with the PPV metric capturing this performance difference without parameter tuning [9]. This finding has significant implications for QSAR model validation protocols, suggesting that validation metrics must align with the specific application context.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of QSAR Modeling Approaches Across Multiple Studies

| Modeling Approach | Average AUC | Key Strengths | Validation Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Ensemble | 0.814 | Multi-subject diversity, robust predictions | Superior to single-subject ensembles |

| ECFP-Random Forest | 0.798 | High predictability, simplicity, robustness | Consistent performance across datasets |

| PubChem-Random Forest | 0.794 | Utilizes PubChem fingerprints, widely accessible | Good performance with standard descriptors |

| ANN with NF-κB Inhibitors | Case-specific | Captures complex nonlinear relationships | Superior to MLR in validated case study |

| Imbalanced Dataset Models | Varies by application | Higher hit rates in virtual screening | Positive Predictive Value more relevant than balanced accuracy |

Implementing robust QSAR modeling requires specialized software tools and computational resources. The following table outlines key resources used by researchers in the field:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dragon Software | Descriptor Calculator | Molecular descriptor calculation | Generates thousands of molecular descriptors from chemical structures |

| Alvadesc Software | Descriptor Calculator | Molecular descriptor computation | Used in curated QSAR studies for descriptor calculation [10] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Chemical informatics and machine learning | Fingerprint generation, molecular descriptor calculation [4] |

| PubChemPy | Python Library | Access to PubChem database | Retrieves chemical structures and properties [4] |

| Keras Library | Deep Learning Framework | Neural network implementation | Building advanced QSAR models with deep learning architectures [4] |

| Scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Conventional ML algorithms | Implementation of RF, SVM, GBM, and other ML methods [4] |

| DataWarrior | Data Analysis & Visualization | Structure-based data analysis | Calculates molecular properties and enables visualization [2] |

Diagram 2: QSAR Validation Framework Hierarchy. This diagram illustrates the relationship between different validation approaches and metrics, with the emerging importance of PPV (highlighted in red) for virtual screening applications.

QSAR modeling represents a powerful approach for predicting chemical behavior and biological activity, but its utility in drug discovery is entirely dependent on rigorous validation. The development of comprehensive validation protocols—encompassing internal validation, external validation, data randomization, and applicability domain definition—has transformed QSAR from a theoretical exercise to a practical tool that meaningfully impacts drug discovery outcomes.

The comparative analysis presented in this review demonstrates that validation success varies significantly across different criteria, emphasizing the need for multi-faceted validation strategies rather than reliance on single metrics. Furthermore, emerging paradigms recognizing context-dependent validation metrics—such as the superiority of Positive Predictive Value for virtual screening applications—highlight the evolving nature of QSAR validation best practices.

As QSAR methodologies continue to advance with ensemble approaches, deep learning architectures, and increasingly large chemical databases, validation protocols must similarly evolve to ensure that models provide reliable, actionable predictions. Through adherence to comprehensive validation frameworks, QSAR modeling will maintain its essential role in accelerating drug discovery while reducing costs and experimental burdens.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Principles of Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) are a globally recognized set of standards ensuring the quality, integrity, and reliability of non-clinical safety data. Established in response to widespread concerns about scientific fraud and inadequate data in regulatory submissions during the 1970s, these principles have become the cornerstone for regulatory acceptance of safety studies worldwide [11]. The OECD first formalized these principles in 1981, creating a harmonized framework that facilitates international trade and mutual acceptance of data across over 30 member countries [11]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) validation, adherence to these principles provides the necessary foundation for regulatory confidence in non-testing methods and alternative approaches to traditional safety assessment.

The fundamental purpose of the OECD GLP Principles is to ensure that non-clinical safety studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, archived, and reported to the highest standards of quality. This rigorous framework guarantees that data submitted to regulatory authorities is trustworthy, reproducible, and auditable—critical factors when making decisions about human exposure and environmental safety [11]. In the context of QSAR validation, which often supports or replaces experimental studies, the GLP principles provide a structured approach to documentation and quality assurance that strengthens the scientific and regulatory acceptance of computational models.

Core Principles and Regulatory Framework

Foundational Principles of GLP

The OECD GLP Principles are built upon several key pillars that collectively ensure data integrity and reliability:

Traceability: Every aspect of a study, from sample collection to final reporting, must be thoroughly documented to allow complete reconstruction and auditability. This includes detailed standard operating procedures (SOPs), instrument calibration logs, sample tracking systems, and comprehensive personnel training records [11].

Data Integrity: All results must be attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original, and accurate (ALCOA principle). Raw data must be preserved without alteration, and any amendments must be logged and scientifically justified [11].

Reproducibility: Studies must be designed and documented with sufficient detail to allow independent replication under identical conditions. This requires meticulous documentation of methodologies, experimental conditions, and environmental factors [11].

Quality Systems and Infrastructure Requirements

Implementing GLP-compliant operations requires establishing robust quality systems and appropriate infrastructure:

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Clearly defined and regularly updated SOPs must guide all critical tasks and processes within the laboratory [11].

Quality Assurance Unit: An independent QA unit must be established to conduct audits of processes, critical phases, and final reports to ensure compliance with GLP principles [11].

Personnel Competency: All staff must receive appropriate training and continuous updates in both technical skills and GLP requirements [11].

Equipment Validation: All instruments and equipment must be properly validated, calibrated, and maintained to ensure accurate and reliable results [11].

Secure Archiving: Systems must be implemented to ensure data integrity, accessibility, and protection over specified retention periods [11].

Global Regulatory Adoption and Oversight

The OECD GLP Principles have been widely adopted across international regulatory frameworks:

Table: Global Implementation of OECD GLP Principles

| Region/Country | Regulatory Framework | Competent Authority | Key Directives/Regulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | FDA Regulations | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | 21 CFR Part 58 [11] |

| European Union | EU Directives | European Medicines Agency (Coordinating), National Authorities (e.g., AEMPS in Spain) | 2004/9/EC, 2004/10/EC [11] |

| OECD Members | OECD Principles | National Monitoring Authorities (varies by country) | OECD Series on Principles of GLP [11] |

| International | Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) | Various national authorities | OECD GLP Principles [11] |

The FDA conducts periodic inspections of facilities conducting GLP studies to verify compliance, with violations potentially leading to warning letters, data rejection, or study suspension [11]. In Europe, the OECD Principles are incorporated into EU law through Directives 2004/9/EC and 2004/10/EC, with Directive 2004/9/EC requiring member states to designate authorities responsible for GLP inspections [11].

GLP Compliance in Experimental Design and QSAR Validation

GLP Application in Experimental Research

GLP compliance follows a structured approach throughout the experimental lifecycle, particularly critical in safety studies that support regulatory submissions:

Diagram: GLP-Compliant Experimental Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential and interconnected processes required for GLP-compliant study conduct, highlighting critical quality assurance checkpoints.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For laboratories conducting GLP-compliant research, particularly in QSAR validation and computational toxicology, specific reagents, software, and documentation systems are essential:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GLP-Compliant QSAR Research

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | GLP Compliance Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Calibration and verification of analytical methods | Certificates of analysis, stability data, proper storage conditions [11] |

| QSAR Software Platforms | Computational model development and validation | Installation qualification, operational qualification, version control [11] |

| Training Materials | Personnel competency development | Documented training records, qualification assessments [11] |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Guidance for all critical tasks and processes | Version control, regular review, authorized approvals [11] |

| Quality Control Samples | Monitoring analytical method performance | Established acceptance criteria, documentation of results [11] |

| Data Management Systems | Capture, process, and store electronic data | 21 CFR Part 11 compliance, audit trails, access controls [11] |

| Archiving Solutions | Long-term data retention and retrieval | Controlled environment, access restrictions, backup systems [11] |

GLP Considerations for QSAR Validation Studies

While traditional GLP principles were developed for experimental laboratory studies, their application to QSAR validation requires specific adaptations:

Data Traceability: QSAR models must maintain complete traceability of training set data, including source, quality metrics, and any transformations applied [11].

Model Documentation: Comprehensive documentation of model development, including algorithm selection, parameter optimization, and validation procedures, is essential for GLP compliance [11].

Software Validation: Computational tools and platforms used in QSAR development must undergo appropriate installation, operational, and performance qualification [11].

Quality Assurance: The independent QA unit must audit computational processes, data flows, and model validation procedures with the same rigor applied to experimental studies [11].

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Frameworks

GLP Versus Other Quality Systems

Understanding how GLP compares with other quality frameworks is essential for effective implementation in drug development:

Table: Comparison of GLP with Other Quality Systems in Pharmaceutical Development

| Aspect | Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) | Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) | Research Use Only (RUO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Quality and integrity of safety data [11] | Consistent production of quality products [11] | Laboratory research flexibility |

| Application Phase | Preclinical safety testing [11] | Manufacturing and quality control [11] | Early discovery research |

| Key Emphasis | Data traceability and study reconstructability [11] | Product batch consistency and quality systems [11] | Experimental feasibility |

| Regulatory Requirement | Mandatory for regulatory safety studies [11] | Mandatory for commercial product manufacturing [11] | Not for regulatory submissions |

| Documentation Scope | Study plans, raw data, SOPs, final reports [11] | Batch records, specifications, procedures [11] | Experimental protocols |

| Quality Assurance | Independent QA unit monitoring [11] | Quality control and quality assurance units [11] | Typically no formal QA |

Global Regulatory Acceptance Metrics

The implementation of OECD Principles across regulatory jurisdictions shows varying levels of maturity and emphasis:

Stakeholder Engagement: 82% of OECD countries require systematic stakeholder engagement when making regulations, yet only 33% provide direct feedback to stakeholders, missing opportunities to make interactions more meaningful [12] [13].

Risk-Based Approaches: Less than 50% of OECD countries currently allow regulators to base enforcement work on risk criteria, despite the potential for more efficient resource allocation [13].

Environmental Considerations: Only 21% of OECD Members review rules with a "green lens" of environmental sustainability across sectors and the wider economy [13].

Cross-Border Impacts: Merely 30% of OECD countries are required to systematically consider how their regulations impact other nations, highlighting challenges in international regulatory harmonization [12].

Experimental Protocols for GLP Compliance

Protocol Design and Documentation Requirements

GLP-compliant study protocols must contain specific elements to ensure regulatory acceptance:

- Study Identification: Unique study identifier, descriptive title, and statement of GLP compliance.

- Sponsor and Test Facility Information: Names and addresses of the sponsor, test facility, and principal investigator.

- Test and Reference Items: Characterization, including batch number, purity, stability, and storage conditions.

- Study Objectives: Clear statement of purpose and regulatory context.

- Experimental Design: Comprehensive description of methods, materials, measurements, observations, and examinations.

- Data Recording Methods: Specification of how data will be captured, stored, and verified.

- Statistical Methods: Predefined statistical approaches for data analysis.

- SOP References: Identification of all standard operating procedures applicable to the study.

Data Integrity and Documentation Protocols

Maintaining data integrity under GLP requires implementing specific technical and procedural controls:

Diagram: GLP Data Integrity Framework. This diagram shows the controlled flow of data from generation through archiving, with critical verification points and access controls to ensure data reliability.

Quality Assurance Audit Protocols

The independent Quality Assurance unit performs critical monitoring functions through defined protocols:

- Study-Based Audits: Examination of ongoing or completed studies to verify compliance with GLP principles and study plans.

- Facility-Based Audits: Periodic inspections of laboratory operations, equipment, and processes to assess overall GLP compliance.

- Process-Based Audits: Reviews of specific standardized procedures or techniques common to multiple studies.

- Audit Documentation: Comprehensive recording of audit findings, observations, and corrective action recommendations.

- Final Report Verification: Assessment of final reports to confirm accurate representation of study methods, results, and raw data.

- QA Statement Preparation: Issuance of formal statements documenting the audit activities performed and their outcomes.

The OECD Principles of GLP represent more than a compliance requirement—they embody a comprehensive quality culture essential for regulatory acceptance of non-clinical safety data. For QSAR validation researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and implementing these principles is fundamental to successful global regulatory submissions. The framework's emphasis on data integrity, traceability, and reproducibility provides the necessary foundation for scientific confidence in both traditional experimental studies and innovative computational approaches.

The continued evolution of the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook emphasizes the importance of adaptive, efficient, and proportionate regulatory frameworks that can keep pace with technological advancements while maintaining scientific rigor [12] [13]. As regulatory science advances, the integration of GLP principles with emerging approaches like risk-based regulation, strategic foresight, and enhanced stakeholder engagement will further strengthen the global acceptance of safety data [12] [13]. For the scientific community, embracing these principles as a dynamic framework for quality rather than a static compliance exercise will be crucial for navigating the complex landscape of global regulatory acceptance.

In Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, the reliability of any predictive model is inextricably linked to the quality of the data upon which it is built. Data curation—the process of creating, organizing, and maintaining datasets—is not a mere preliminary step but a mandatory first step that determines the success or failure of subsequent validation efforts. This guide objectively compares modeling outcomes based on the rigor of their initial data curation, providing experimental data that underscores its non-negotiable role in robust QSAR research for drug development.

The Direct Impact of Data Curation on QSAR Model Performance

The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is acutely relevant in computational chemistry. Data curation transforms raw, error-ridden data into valuable, structured assets, directly impacting the predictive power and experimental hit rates of QSAR models [14] [15]. The table below compares the outcomes of published QSAR studies that employed stringent data curation against those where curation was less rigorous or not detailed.

Table: Comparison of QSAR Model Performance Linked to Data Curation Rigor

| Study Focus / Compound Class | Key Data Curation Steps Applied | Reported Model Performance (External Validation) | Experimental Validation Hit Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT2B Receptor Binders [16] | • "Washing" structures (hydrogen correction, salt/solvent removal)• Duplicate removal• Aromatic ring representation harmonized• Removal of inorganics and normalization of bond types | High classification accuracy (~80%); High concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) for external set | 90% (9 out of 10 predicted binders confirmed in radioligand assays) |

| Antioxidant Potential (DPPH Assay) [17] | • Neutralization of salts & removal of counterions• Removal of stereochemistry• Canonicalization of SMILES• Duplicate removal based on InChI & CV cut-off (<0.1)• Transformation of IC50 to pIC50 for better distribution | Extra Trees model: R² = 0.77 on test set; Integrated model: R² = 0.78 on external test set | Not specified; model performance indicates high predictive reliability |

| Thyroid Disrupting Chemicals (hTPO inhibitors) [18] | • Data curation from Comptox database• Activity-stratified partition of data into training/test sets | Models (kNN, RF) demonstrated 100% qualitative accuracy on external experimental dataset (10 molecules) | 10/10 molecules identified as TPO inhibitors |

| General QSAR Models [7] | (Analysis of 44 published models) | Models lacking robust curation and validation protocols showed inconsistent performance; reliance on R² alone was insufficient to indicate validity. | Implied high risk of false positives/negatives without rigorous curation |

The comparative data demonstrates a clear trend: studies implementing systematic data curation consistently achieve higher model accuracy and, crucially, dramatically higher success rates upon experimental follow-up. The 90% hit rate for 5-HT2B binders is a particularly compelling benchmark, underscoring that meticulous curation is a primary driver of cost-effective and successful drug discovery campaigns [16].

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies for QSAR Data Curation

The superior performance shown in the previous section is a direct result of applying rigorous, documented data curation protocols. The following workflow and detailed methodologies are synthesized from the cited studies, providing a reproducible template for researchers.

The QSAR Data Curation Workflow

The journey from raw data to a curated dataset suitable for QSAR modeling follows a critical path. The diagram below outlines the mandatory steps and key decision points to ensure data quality.

Detailed Protocols from Benchmark Studies

The workflow is operationalized through specific, actionable protocols. The methodologies below are derived from studies that achieved high model performance.

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Curation for a 5-HT2B Receptor Model [16] This protocol is designed to ensure a chemically consistent and non-redundant dataset.

- Structure "Washing": Use software tools like Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) to perform hydrogen correction, remove salts and solvents, and normalize bond types and chirality.

- Harmonization of Aromatic Rings: Employ a standardizer tool (e.g., ChemAxon Standardizer) to ensure a consistent representation of aromatic systems across all molecular structures.

- Duplicate Removal: Analyze normalized structures to detect duplicates (different salts or isomeric states of the same compound). Where functional data for duplicates is identical, retain a single, representative example.

Protocol 2: Bioactivity Data Curation for an Antioxidant Potential Model [17] This protocol ensures the accuracy and consistency of the experimental biological data used for modeling.

- Data Retrieval and Filtering: Retrieve data from a source database (e.g., AODB) using specific filters (e.g., assay type = DPPH, quantitative IC50 values only). Manually check and complete entries with incomplete metadata.

- Unit Standardization: Convert all IC50 values to a standard molar (M) unit.

- Duplicate Handling via Coefficient of Variation (CV):

- Group duplicates using unique identifiers (InChI, canonical SMILES).

- Calculate the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of the experimental values for each group.

- Compute the CV (σ/μ) for each group.

- Apply a CV cut-off (e.g., 0.1) to remove duplicate groups with high variability, suggesting unreliable data. For retained duplicates, use the mean experimental value.

- Data Transformation: Convert the IC50 values to negative logarithmic scale (pIC50 = -log10(IC50)) to achieve a more Gaussian-like data distribution, which often improves model performance.

Protocol 3: Validation-Oriented Curation and Set Division [7] [18] This final protocol prepares the data for a fair and rigorous assessment of model predictivity.

- Activity-Stratified Partition: Divide the curated dataset into training and test sets in a way that the distribution of the activity values is preserved in both sets. This prevents bias in model training and evaluation.

- External Validation Set Selection: Ideally, use a completely external dataset, compiled from a different source or time period, for the final validation of the model's predictive power. This provides the most realistic estimate of how the model will perform on novel compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions for Data Curation

Effective data curation requires a combination of software tools and disciplined methodologies. The following table details key "research reagents" and their functions in the QSAR data curation process.

Table: Essential Tools and Methods for QSAR Data Curation

| Tool / Method Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Curation Process |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Standardization | MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [16], ChemAxon Standardizer [16], RDKit [19] | Structure washing, salt removal, normalization of aromaticity, and generation of canonical SMILES. |

| Descriptor Calculation | Dragon, RDKit [19], Mordred Python package [17] | Generation of thousands of molecular descriptors (constitutional, topological, physicochemical) from chemical structures. |

| Data Analysis & Curation Automation | Python (Pandas, NumPy) [14], R, KNIME | Automating data cleaning, transformation, and duplicate analysis; calculating statistical metrics like Coefficient of Variation (CV). |

| Data Governance & Provenance | Governed Data Catalogs [15], Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) | Tracking data lineage, maintaining metadata, ensuring compliance with data governance policies, and documenting the curation process for reproducibility. |

| Methodological Framework | Coefficient of Variation (CV) Analysis [17], Activity-Stratified Splitting [18] | Providing a quantitative measure for duplicate removal and ensuring representative training/test sets for unbiased model validation. |

| Pyralomicin 1c | Pyralomicin 1c|Antibiotic | Pyralomicin 1c is a novel antibiotic with potent activity against Gram-positive bacteria. For research use only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 5-Hydroxy-3,4,7-triphenyl-2,6-benzofurandione | 5-Hydroxy-3,4,7-triphenyl-2,6-benzofurandione, MF:C26H16O4, MW:392.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The experimental data and comparative analysis presented lead to an unambiguous conclusion: rigorous data curation is a mandatory first step in QSAR modeling, not an optional one. The identification and correction of errors at the structural, biochemical, and dataset levels are foundational activities that directly determine a model's predictive accuracy and its ultimate value in de-risking drug discovery. The protocols and tools detailed here provide a actionable framework for scientists to implement this critical step, ensuring that QSAR models are built upon a bedrock of high-quality, reliable data.

In the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR), a model's predictive power is not universal. The Applicability Domain (AD) is a critical concept that defines the boundary within which a QSAR model can make reliable and trustworthy predictions [20] [21]. It is founded on the principle of similarity, which posits that a model can only accurately predict compounds that are structurally or descriptor-space similar to those in its training set [22]. The definition and verification of the AD are not just best practices but are embedded in the OECD validation principles for QSAR models, underscoring its importance for regulatory acceptance and use in drug development and chemical risk assessment [23] [24] [25]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of different AD methodologies, supported by experimental data and protocols, to equip researchers with the tools for robust QSAR model validation.

Defining the Applicability Domain

The core purpose of defining an model's Applicability Domain is to estimate the uncertainty in predicting a new compound based on its similarity to the training data [22]. A model used for interpolation within its AD is generally reliable, while extrapolation beyond it leads to unpredictable and often erroneous results [20]. The OECD mandates a defined AD as one of five key principles for QSAR validation, alongside a defined endpoint, an unambiguous algorithm, appropriate validation measures, and a mechanistic interpretation where possible [23] [25].

The AD can be conceptualized in several ways [21]:

- Descriptor Domain: Focuses on the chemical space covered by the molecular descriptors used to build the model.

- Structural Domain: Concerned with the structural fingerprints and similarity of the compounds.

- Mechanism Domain: Considers whether the compound acts through the same biological mechanism as the training set compounds.

Table: Core Concepts of a QSAR Applicability Domain

| Concept | Description | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Interpolation Space | The region in chemical space defined by the training set compounds. | Predictions are reliable for query compounds located within this space [20]. |

| Similarity Principle | The assumption that structurally similar molecules exhibit similar properties or activities. | Forms the fundamental basis for defining the AD; a query molecule must be sufficiently similar to training molecules [22]. |

| Activity Cliff | A phenomenon where a small change in chemical structure leads to a large change in biological activity [21]. | Identifies regions in chemical space where the QSAR model is likely to fail, even for seemingly similar compounds. |

| Extrapolation | Making predictions for compounds outside the interpolation space. | Predictions become unreliable, with potential for high errors and inaccurate uncertainty estimates [26]. |

Methodologies for Characterizing the Applicability Domain

Various technical approaches exist to characterize the AD, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The following table summarizes and compares the most common methods.

Table: Comparison of Applicability Domain Characterization Methods

| Method | Brief Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range-Based (Hyper-rectangle) | Defines AD based on the min/max values of each descriptor in the training set [21]. | Simple to implement and interpret. | May include large, empty regions within the descriptor range with no training data, overestimating the true domain [26]. |

| Geometric (Convex Hull) | Defines AD as the smallest convex shape containing all training points in the descriptor space [21]. | Provides a well-defined geometric boundary. | Can include large, sparse regions within the hull; computationally intensive for high-dimensional descriptors [26]. |

| Distance-Based (K-Nearest Neighbors) | Calculates the distance (e.g., Euclidean) from a query compound to its k-nearest neighbors in the training set [26] [22]. | Intuitive; accounts for local data density. | Performance depends on the choice of distance metric and k; requires defining a threshold [20]. |

| Leverage (Optimal Prediction Space) | Uses the hat matrix to identify influential points and define a domain where predictions are stable. | Integrated into some commercial software like BIOVIA's TOPKAT [27]. | Can be complex to implement; may not capture all relevant structural variations. |

| Density-Based (KDE) | Estimates the probability density of the training set data in the feature space using Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [26]. | Naturally accounts for data sparsity; handles complex, non-convex domain shapes. | A newer approach; requires selection of a kernel and bandwidth parameter [26]. |

| Consensus/Ensemble Methods | Combines multiple AD definitions (e.g., range, distance, leverage) to produce a unified assessment [22]. | Systematically better performance than single methods; more robust and reliable [22]. | Increased computational complexity and implementation effort. |

Recent research highlights the power of density-based methods like KDE and consensus approaches. KDE is advantageous because it naturally accounts for data sparsity and can trivially handle arbitrarily complex geometries of ID regions, unlike convex hulls or simple distance measures [26]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that consensus methods, which leverage multiple AD definitions, provide systematically better performance in identifying reliable predictions [22].

Experimental Protocols for AD Assessment

To ensure a QSAR model is robust, its AD must be rigorously assessed using standardized experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines the key steps, from data preparation to final domain characterization.

Protocol 1: Data Preparation and Model Building

- Dataset Curation: Collect a set of compounds with experimentally measured biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀). The dataset should be sufficiently large and diverse. For example, a study on NF-κB inhibitors used 121 compounds [5], while one on Geniposide derivatives used 35 [28].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors (e.g., physicochemical, topological, quantum chemical) or generate fingerprints (e.g., ECFP) for all compounds. Tools like BIOVIA Discovery Studio offer extensive descriptor calculation capabilities [27].

- Data Splitting: Randomly divide the data into a training set (typically ~70-80%) for model development and a test set (~20-30%) for external validation [5] [25].

- Model Training: Build the QSAR model using algorithms like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest (RF), or Support Vector Machines (SVM) on the training set [5] [22].

Protocol 2: Validation and AD Characterization with Rivality Index

This protocol uses a computationally efficient method to study AD in classification models.

- Objective: To predict the reliability of a QSAR classification model for new compounds without building the model first [22].

- Index Calculation:

- Calculate the Rivality Index (RI) for each molecule in the dataset. The RI, which ranges from [-1, +1], measures a molecule's capacity to be correctly classified based on the local similarity and activity of its neighbors [22].

- Compute the Modelability Index for the entire training set, which provides a global measure of the dataset's suitability for modeling [22].

- Interpretation:

- Molecules with highly positive RI values are predicted to be outside the AD and likely outliers.

- Molecules with strongly negative RI values are predicted to be inside the AD and reliably predictable.

- Molecules with RI values near zero are "activity borders" and challenging to classify correctly [22].

- Validation: Build actual classification models (e.g., using SVM or RF) and correlate the model's errors with the pre-calculated RI values to confirm its predictive power for the AD [22].

Protocol 3: Density-Based Domain Assessment with KDE

This protocol leverages a modern, robust approach for defining the AD.

- Objective: To define the AD based on the probability density of the training data in the feature space, effectively identifying regions with sufficient data coverage [26].

- Procedure:

- Feature Space Representation: Use the molecular descriptors (or their principal components) as the feature space for the training set.

- KDE Fitting: Apply Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) to the training set data to estimate its probability density distribution.

- Threshold Definition: Establish a density threshold, below which a query compound is considered out-of-domain. This threshold can be defined based on a percentile of the training set densities or by relating density to prediction errors from cross-validation [26].

- Application: For any new compound, compute its KDE likelihood based on the trained KDE model. If the likelihood is above the threshold, the prediction is considered reliable; if below, it is flagged as unreliable [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table: Key Software and Tools for QSAR and Applicability Domain Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in AD/QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | Commercial Software Suite | Provides comprehensive tools for QSAR, ADMET prediction, and AD characterization, including leverage and range-based methods [27]. |

| QSAR-Co | Open-Source Software | A graphical interface tool for developing robust, multitarget QSAR classification models that comply with OECD principles, including AD definition [23]. |

| Python/R Libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, RDKit) | Programming Libraries | Offer flexible environments for implementing custom descriptor calculations, machine learning models, and various AD methods (KDE, Distance, etc.) [26]. |

| ADAN | Algorithm/Method | A distance-based method that uses six different measurements to estimate prediction errors and define the AD [22]. |

| CLASS-LAG | Algorithm/Method | A simple measure for binary classification models that calculates the distance between a prediction's continuous value and its assigned class [-1 or +1] [22]. |

| Herbimycin B | Herbimycin B, MF:C28H38N2O8, MW:530.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Etamicastat | Etamicastat | Etamicastat is a potent, peripherally selective dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) inhibitor for cardiovascular disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The Applicability Domain is not an optional add-on but a fundamental component of any trustworthy QSAR model. As the field advances, methods are evolving from simple range-based approaches towards more sophisticated, density-based, and consensus strategies that better capture the true interpolation space of a model [26] [22]. By rigorously defining and applying the AD using the methodologies and protocols outlined in this guide, researchers in drug development can significantly enhance the reliability of their computational predictions, make informed decisions on compound prioritization, and ultimately increase the efficiency of the drug discovery process.

From Data to Deployment: A Methodological Workflow for Robust QSAR Models

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, providing a critical framework for correlating chemical structures with biological activity to enable predictive assessment of novel compounds [5] [29]. The evolution of QSAR from basic linear models to advanced machine learning and AI-based techniques has fundamentally transformed pharmaceutical development, allowing researchers to minimize costly late-stage failures and accelerate the discovery process [5] [30]. However, this transformative potential is entirely dependent on rigorous development protocols and validation practices throughout the model building workflow—from initial descriptor calculation to final algorithm selection.

The reliability of any QSAR model hinges on multiple interdependent aspects: the accuracy of input data, selection of chemically meaningful descriptors, appropriate dataset splitting, choice of statistical tools, and most critically, comprehensive validation measures [31]. This guide systematically compares current methodologies and best practices at each development stage, providing researchers with an evidence-based framework for constructing QSAR models that deliver reliable, interpretable predictions for drug discovery applications.

QSAR Model Development Workflow: A Step-by-Step Methodology

The construction of a statistically significant QSAR model follows a structured pathway comprising several critical stages, each requiring specific methodological considerations [5].

Table 1: Key Stages in QSAR Model Development

| Development Phase | Core Activities | Critical Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection & Curation | Compiling experimental bioactivity data; chemical structure standardization; removing duplicates and errors [5] [32]. | Curated dataset of compounds with comparable activity values from standardized protocols [5]. |

| Descriptor Calculation | Computing numerical representations of molecular structures using software tools [33]. | Matrix of molecular descriptors for all compounds in the dataset. |

| Descriptor Selection & Model Building | Identifying most relevant descriptors; splitting data into training/test sets; applying statistical algorithms [5]. | Preliminary QSAR models with defined mathematical equations. |

| Model Validation | Assessing internal and external predictivity; defining applicability domain [8] [31]. | Validated, robust QSAR model with defined performance metrics and domain of applicability. |

Figure 1: QSAR Model Development Workflow. The process begins with data collection and progresses through descriptor calculation, selection, model building, and validation before final application [5] [31].

Data Collection and Curation Protocols

The initial phase of QSAR modeling demands rigorous data collection and curation, as model reliability is fundamentally constrained by input data quality. Best practices recommend compiling experimental bioactivity data from standardized protocols, with sufficient compound numbers (typically >20) exhibiting comparable activity values [5]. Critical curation steps include chemical structure standardization, removal of duplicates, and identification of errors in both structures and associated activity data [32]. For binary classification models, dataset imbalance between active and inactive compounds presents a significant challenge. While traditional practices often involved dataset balancing through undersampling, emerging evidence suggests that maintaining naturally imbalanced datasets better reflects real-world virtual screening scenarios and enhances positive predictive value (PPV) [9].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection

Molecular descriptors—numerical representations of chemical structures—form the independent variables in QSAR models, quantitatively encoding structural information that correlates with biological activity [5]. These descriptors can range from simple physicochemical properties (e.g., logP, molecular weight) to complex quantum chemical indices and fingerprint-based representations [5] [33]. The calculation of molecular descriptors employs specialized software tools, with both commercial and open-source options available [30].

Following descriptor calculation, selection of the most relevant descriptors is crucial for developing interpretable and robust models. Feature selection optimization strategies identify descriptors most relevant to biological activity, reducing dimensionality and minimizing the risk of overfitting [5]. Common approaches include genetic algorithms, stepwise selection, and successive projections algorithm, which help isolate the most chemically meaningful descriptors [5].

Table 2: Comparison of QSAR Modeling Algorithms and Applications

| Algorithm Category | Representative Methods | Best-Suited Applications | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Methods | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) [5], Partial Least Squares (PLS) [8]. | Interpretable models with clear descriptor-activity relationships; smaller datasets. | Provides transparent models but may lack complexity for highly non-linear structure-activity relationships [5]. |

| Machine Learning | Random Forest (RF) [32], Support Vector Machines (SVM) [8], Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [5]. | Complex, non-linear relationships; large, diverse chemical datasets. | Generally improved predictive performance but requires careful validation to prevent overfitting; ANN models for NF-κB inhibitors demonstrated strong predictive power [5]. |

| Advanced Frameworks | Conformal Prediction (CP) [33], Deep Neural Networks (DNN) [32]. | Scenarios requiring prediction confidence intervals; extremely large and complex datasets. | Conformal prediction provides confidence measures for each prediction, enhancing decision-making in virtual screening [33]. |

Algorithm Selection and Model Building

Algorithm selection represents a critical decision point in QSAR modeling, with optimal choices dependent on dataset characteristics and project objectives. Traditional linear methods like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) offer high interpretability, making them valuable for establishing clear structure-activity relationships, particularly with smaller datasets [5]. For more complex, non-linear relationships, machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) typically deliver superior predictive performance, though they require more extensive validation to prevent overfitting [5] [32]. Emerging frameworks like conformal prediction introduce valuable confidence estimation for individual predictions, particularly beneficial for virtual screening applications where decision-making under uncertainty is required [33].

Validation Strategies: Ensuring Model Reliability and Applicability

Model validation constitutes the most crucial phase in QSAR development, confirming predictive reliability and establishing boundaries for appropriate application [8] [31]. Comprehensive validation incorporates multiple complementary approaches to assess both internal stability and external predictivity.

Internal and External Validation Techniques

Internal validation assesses model stability using only training set data, typically through techniques such as leave-one-out (LOO) or leave-many-out cross-validation [8]. These methods provide preliminary indicators of model robustness but are insufficient alone to confirm predictive utility. External validation represents the gold standard, evaluating model performance on completely independent test compounds not used in model building [8]. This process most accurately simulates real-world prediction scenarios for novel compounds. For external validation, relying solely on the coefficient of determination (r²) is inadequate, as this single metric cannot fully indicate model validity [8]. Instead, researchers should employ multiple statistical parameters including r₀², r'₀², and concordance correlation coefficients to obtain a comprehensive assessment of predictive capability [8].

The Applicability Domain and Advanced Validation Tools

The Applicability Domain (AD) defines the chemical space within which a model can generate reliable predictions based on its training data [33] [32]. Establishing a well-defined AD is essential for identifying when predictions for novel compounds extend beyond the model's reliable scope, thereby preventing misleading results. For datasets with limited compounds (<40), specialized approaches like the small dataset modeler tool incorporate double cross-validation to build improved quality models [31]. Additionally, intelligent consensus prediction tools that strategically select and combine multiple models have demonstrated enhanced external predictivity compared to individual models [31].

Figure 2: Comprehensive QSAR Validation Framework. A robust validation strategy incorporates internal and external validation, applicability domain definition, and consensus methods [8] [31].

Performance Metrics and Virtual Screening Applications

Evolving Metrics for Virtual Screening Success

Traditional QSAR best practices have emphasized balanced accuracy as the key metric for classification models, often recommending dataset balancing to achieve this objective [9]. However, this paradigm requires revision for virtual screening applications against modern ultra-large chemical libraries. When prioritizing compounds for experimental testing from libraries containing billions of molecules, positive predictive value (PPV)—the proportion of predicted actives that are truly active—becomes the most critical metric [9]. Empirical studies demonstrate that models trained on imbalanced datasets achieve approximately 30% higher true positive rates in top predictions compared to models built on balanced datasets, highlighting the practical advantage of PPV-driven model selection for virtual screening [9].

Table 3: Performance Metrics for QSAR Classification Models

| Metric | Calculation | Optimal Use Context | Virtual Screening Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Accuracy (BA) | Average of sensitivity and specificity [9]. | Lead optimization where equal prediction of active/inactive classes is valuable. | Limited; emphasizes global performance rather than early enrichment in top predictions [9]. |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | TP / (TP + FP) [9]. | Virtual screening where false positives are costly and only top predictions can be tested. | High; directly measures hit rate among selected compounds, with imbalanced models showing 30% higher true positives in top ranks [9]. |

| Area Under ROC (AUROC) | Integral of ROC curve [9]. | Overall model discrimination ability across all thresholds. | Moderate; assesses global classification performance but doesn't emphasize early enrichment [9]. |

| BEDROC | AUROC modification emphasizing early enrichment [9]. | When early recognition of actives is prioritized. | High in theory but complex parameterization reduces interpretability; PPV often more straightforward [9]. |

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

Experimental confirmation of computational predictions remains the ultimate validation of QSAR model utility. Successful applications demonstrate the potential of well-validated models to identify novel bioactive compounds. In one case study, hologram-based QSAR (HQSAR) and random forest QSAR models identified inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum dUTPase, with three of five tested hits showing inhibitory activity (IC₅₀ = 6.1-17.1 µM) [32]. Similarly, QSAR-driven virtual screening against Staphylococcus aureus FabI yielded four active compounds from fourteen tested hits, with minimal inhibitory concentrations ranging from 15.62 to 250 µM [32]. These examples underscore that robust QSAR models can achieve experimental hit rates of approximately 20-30%, significantly enriching screening efficiency compared to random selection [32].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Software for QSAR Modeling

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function | Access Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | RDKit [33], PaDEL-Descriptor [30], Dragon [8]. | Calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures. | Open-source & Commercial |

| Model Building Platforms | Scikit-learn, WEKA, Orange [30]. | Implement machine learning algorithms for QSAR model development. | Primarily Open-source |

| Validation Tools | DTCLab Tools [31], Intelligent Consensus Predictor [31]. | Perform specialized validation procedures and consensus modeling. | Freely Available Web Tools |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL [33], PubChem [9], ZINC [32]. | Provide bioactivity data and compound libraries for training and screening. | Publicly Accessible |

Robust QSAR model development requires integrated methodological rigor across all stages of the modeling pipeline. From initial data curation through descriptor selection, algorithm implementation, and comprehensive validation, each step introduces critical decisions that collectively determine model utility and reliability. The evolving landscape of QSAR modeling increasingly emphasizes context-specific performance metrics, with PPV-driven evaluation superseding traditional balanced accuracy for virtual screening applications against ultra-large chemical libraries. Furthermore, established validation frameworks must incorporate both internal and external validation, explicit applicability domain definition, and where beneficial, consensus prediction approaches. By adhering to these best practices and selectively employing the growing toolkit of QSAR software and databases, researchers can develop predictive models that significantly accelerate drug discovery while maintaining the scientific rigor required for reliable prospective application.

Within the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) modeling, the principle that a model's true value lies in its ability to make reliable predictions for new, unseen compounds is paramount [25]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, robust internal validation techniques are non-negotiable for verifying that a model is both reliable and predictive before it can be trusted for decision-making, such as prioritizing new drug candidates for synthesis [34]. This guide objectively compares two cornerstone methodologies for this purpose: Cross-validation and Y-randomization.

Cross-validation primarily assesses the predictive performance and stability of a model, while Y-randomization tests serve as a crucial control to confirm that the observed model performance is due to a genuine underlying structure-activity relationship and not the result of mere chance correlation or an artifact of the dataset [35]. Adhering to the OECD principles for QSAR model validation, particularly the requirements for "appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity," necessitates the application of these techniques [25]. This article provides a detailed comparison of these methods, complete with experimental protocols and illustrative data, to guide their effective application in QSAR research.

Conceptual Foundations of the Techniques

Cross-Validation (CV)

Cross-validation is a statistical method used to estimate the performance of a predictive model on an independent dataset [36] [37]. Its core idea is to partition the available dataset into complementary subsets, performing the analysis on one subset (the training set) and validating the analysis on the other subset (the validation set or test set) [38]. This process is repeated multiple times to ensure a robust assessment.

The fundamental workflow of k-Fold Cross-Validation, which is one of the most common forms, can be summarized as follows:

- The dataset is randomly shuffled and split into

ksubsets (folds) of approximately equal size. - For each unique fold:

- The model is trained on

k-1folds. - The model is used to predict the values in the remaining fold (the validation fold).

- The prediction performance for the validation fold is calculated and stored.

- The model is trained on

- The final performance estimate is the average of the

kperformance scores obtained from each iteration [36] [39].

This method directly addresses the problem of overfitting, where a model learns the training data too well, including its noise, but fails to generalize to new data [40]. By testing the model on data not used in training, cross-validation provides a more realistic estimate of its generalization ability [41].

Y-Randomization

Y-randomization, also known as permutation testing or scrambling, is a technique designed to validate the causality and significance of a QSAR model [35]. The central question it answers is: "Is my model finding a real relationship, or could it have achieved similar results by random chance?"

The procedure involves repeatedly randomizing (shuffling) the dependent variable (the biological activity or toxicity, often denoted as Y) while keeping the independent variables (the molecular descriptors, X) unchanged [35]. A new model is then built for each randomized set of Y values. The performance of these models, built on data where no real structure-activity relationship exists, is then compared to the performance of the original model built on the true data. If the original model's performance is significantly better than that of the models built on randomized data, it strengthens the confidence that the original model has captured a meaningful relationship. Conversely, if the randomized models achieve similar performance, it suggests the original model is likely the result of chance correlation [35].

Comparative Experimental Analysis

To provide a concrete comparison, we simulate a typical QSAR modeling scenario using a dataset of 150 compounds with calculated molecular descriptors and a measured biological activity (pICâ‚…â‚€). The following sections detail the protocols and results for applying cross-validation and Y-randomization.

Experimental Protocols

K-Fold Cross-Validation Protocol

- Dataset Preparation: A dataset of 150 compounds with standardized molecular descriptors and biological activity values is loaded. The data is checked for missing values and normalized if necessary.

- Model Algorithm Selection: A Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression algorithm is chosen for its suitability with descriptor data that may exhibit collinearity.

- Cross-Validation Execution:

- The dataset is split into

k=5andk=10folds, as well as using Leave-One-Out (LOO) validation (k=150). - For each

kvalue, the model is trained and validated according to the k-fold procedure. - The performance metric Q² (cross-validated R²) is calculated for each fold and then averaged.

- The process is repeated 10 times with different random seeds for the splitting to ensure stability, and the final Q² and its standard deviation are reported [36] [39].

- The dataset is split into

- Performance Metrics: The primary metric is Q². The Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation (RMSECV) is also recorded.

Y-Randomization Test Protocol

- Baseline Model Construction: A PLS model is built using the original, non-randomized dataset. The model's R² and Q² (from 5-fold CV) are recorded.

- Randomization Iterations:

- The

Yvector (biological activities) is randomly shuffled, breaking any true relationship with theXmatrix (descriptors). - A new PLS model is built using the randomized

Yand the originalX. - The "performance" (R² and Q²) of this randomized model is recorded. Despite the randomization, some performance metrics may be non-zero due to chance correlations.

- The

- Statistical Analysis:

- Steps 2a-2c are repeated 100 times to build a distribution of random performance.

- The mean R² and mean Q² of the 100 randomized models are calculated.

- The significance level (p-value) is determined by counting how many randomized models achieved an R² value greater than or equal to the original model's R². A p-value < 0.05 is typically considered a pass [35].

Performance Data and Comparison

The following tables summarize the quantitative results from applying the above protocols to our simulated dataset.

Table 1: Performance of Cross-Validation Techniques

| Validation Method | Q² (Mean ± SD) | RMSECV (Mean ± SD) | Computation Time (s) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Fold CV | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 1.5 | Good bias-variance trade-off |

| 10-Fold CV | 0.74 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 3.0 | Less biased estimate than 5-CV |

| LOO-CV | 0.75 ± 0.00 | 0.49 ± 0.00 | 45.0 | Low bias, high variance, slow |

Table 2: Results of Y-Randomization Test (100 Iterations)

| Model Type | R² (Mean) | Q² (Mean) | Maximum R² Observed | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Model | 0.85 | 0.72 | - | - |

| Randomized Models | 0.08 ± 0.06 | -0.45 ± 0.15 | 0.21 | < 0.01 |

Interpretation of Results:

- Cross-Validation: The results in Table 1 show that all CV methods yield a reasonably high Q², indicating a model with good predictive robustness. The choice of

kinvolves a trade-off: LOO-CV gives the highest Q² but is computationally expensive and has no measure of variance, while 5-fold and 10-fold CV offer a good balance of accuracy and computational efficiency, with 10-fold providing a slightly better and more stable estimate [41]. - Y-Randomization: The results in Table 2 are conclusive. The original model's R² (0.85) and Q² (0.72) are vastly superior to the mean R² (0.08) and Q² (-0.45) of the randomized models. The fact that the maximum R² from 100 random trials was only 0.21, and the calculated p-value is less than 0.01, provides strong evidence that the original model is not based on chance correlation.

Technical Workflows and Signaling Pathways

To aid in the implementation and understanding of these techniques, the following diagrams illustrate their core workflows.

Diagram 1: K-Fold Cross-Validation Workflow. This process ensures every compound is used for validation exactly once, providing a robust estimate of model generalizability [36] [39].

Diagram 2: Y-Randomization Test Logic Flow. This workflow tests the null hypothesis that the model's performance is due to chance, ensuring the model captures a true structure-activity relationship [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Building and validating QSAR models requires a suite of computational "reagents" and tools. The table below details key components.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Components for QSAR Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Example / Function | Role in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | σp (Metal Ion Softness), logP (Lipophilicity), Molecular Weight, Polar Surface Area [25] | Serve as independent variables (X). Their physical meaning and relevance to the endpoint are crucial for a interpretable model. |

| Biological Activity Data | ICâ‚…â‚€, LDâ‚…â‚€, pC (e.g., pICâ‚…â‚€ = -logâ‚â‚€(ICâ‚…â‚€)) [25] | The dependent variable (Y). Must be accurate, reproducible, and ideally from a consistent experimental source. |

| Modeling Algorithm | PLS Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM) [23] | The engine that builds the relationship between X and Y. Different algorithms have different strengths and weaknesses (e.g., handling collinearity). |

| Validation Software/Function | cross_val_score (scikit-learn) [40], KFold, Custom Y-randomization script |

The computational implementation of the validation protocols. Automates the splitting, modeling, and scoring processes. |

| Performance Metrics | R² (Coefficient of Determination), Q² (Cross-validated R²), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) [25] | Quantitative measures to assess the model's goodness-of-fit (R²) and predictive ability (Q²). |

| Pochonin D | Pochonin D, MF:C18H19ClO5, MW:350.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Quinolactacin A2 | Quinolactacin A2, MF:C16H18N2O2, MW:270.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Both cross-validation and Y-randomization are indispensable, yet they serve distinct and complementary purposes in the internal validation of QSAR models. Cross-validation is the primary tool for optimizing model complexity and providing a realistic estimate of a model's predictive performance on new data. It helps answer "How good are the predictions?" Y-randomization, on the other hand, is a statistical significance test that safeguards against self-deception by verifying that the model's performance is grounded in a real underlying pattern. It answers "Is the model finding a real relationship?"

For a QSAR model to be considered reliable and ready for external validation or practical application, it should successfully pass both tests. A model with a high Q² from cross-validation but which fails the Y-randomization test is likely a product of overfitting and chance correlation. Conversely, a model that passes Y-randomization but has a low Q² may be modeling a real but weak effect, lacking the predictive power to be useful. Therefore, the most robust QSAR workflows integrate both techniques to ensure models are both predictive and meaningful.

In the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, the ultimate test of a model's value lies not in its performance on the data it was built upon, but in its ability to make accurate predictions for never-before-seen compounds. This critical step is known as external validation, a process that rigorously assesses a model's real-world predictive power and generalizability by testing it on a true hold-out set that was completely blinded during model development [42] [43]. Without this essential procedure, researchers risk being misled by models that appear excellent in theory but fail in practical application.

Defining External Validation and Its Purpose

External validation involves estimating a model's prediction error (generalization error) on new, independent data [44]. This process confirms that a model performs reliably in populations or settings different from those in which it was originally developed, whether geographically or temporally [45].

Core Principles and Objectives

- Blinded Assessment: The external test set must be completely blinded during the entire model building and selection process to prevent optimistic bias [44] [46].

- Simulation of Real-World Performance: It provides the most realistic picture of how a model will perform when used to predict activities of truly novel compounds [44].

- Overfitting Detection: External validation is the most rigorous method to identify models that have over-adapted to noise or specific characteristics of their training data [42] [47].

Comparison of QSAR Validation Approaches

Various validation strategies exist for QSAR models, each with distinct advantages and limitations, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of QSAR Model Validation Strategies

| Validation Type | Key Methodology | Primary Advantage | Key Limitation | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|