New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in Ecotoxicology: A Modern Framework for Environmental Risk Assessment

This article provides a comprehensive overview of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and their transformative role in ecotoxicology.

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in Ecotoxicology: A Modern Framework for Environmental Risk Assessment

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and their transformative role in ecotoxicology. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles defining NAMs as a suite of non-animal technologies for chemical hazard and risk assessment. The scope ranges from core in vitro and in silico methods to their practical application in integrated testing strategies like IATA and Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs). It further addresses key challenges in the field, including sociological barriers to adoption and concerns over error costs, and provides a forward-looking analysis of validation frameworks and regulatory acceptance, synthesizing how NAMs are accelerating chemical prioritization and modernizing environmental safety evaluations.

What Are NAMs? Redefining Ecotoxicology for the 21st Century

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) represent a transformative shift in toxicological science, moving beyond the simplistic definition of "non-animal methods" to encompass a sophisticated suite of regulatory tools for chemical safety assessment [1]. Formally coined in 2016, the term NAMs describes any technology, methodology, approach, or combination thereof that can provide information on chemical hazard and risk assessment while reducing or replacing vertebrate animal testing [2] [3]. These methodologies deliver improved chemical safety assessment through more protective and/or relevant models that have a reduced reliance on animals, aligning with the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement of animals in research) while also offering significant scientific and economic benefits [1] [4].

The fundamental premise of NAMs-based assessment is that safety decisions should be protective for those exposed to chemicals, utilizing human-relevant biological models rather than attempting to recapitulate animal tests without animals [1]. This represents a paradigm shift from traditional hazard-based classification systems toward a more biologically-informed, risk-based approach that incorporates exposure science and mechanistic understanding [1]. The ultimate goal of this transition is Next Generation Risk Assessment (NGRA), defined as an exposure-led, hypothesis-driven approach that integrates in silico, in chemico, and in vitro approaches, where NGRA is the overall objective and NAMs are the tools used to achieve it [1] [5].

The Expanded Definition and Categorization of NAMs

Comprehensive Taxonomy of NAM Technologies

NAMs encompass a diverse spectrum of technologies and approaches that can be used individually or in integrated testing strategies. The table below categorizes the major types of NAMs and their specific applications in safety assessment.

Table 1: Categorization of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and Their Applications

| NAM Category | Specific Technologies | Primary Applications | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Models | 2D cell cultures, 3D spheroids, organoids, Organ-on-a-Chip systems [3] | Toxicity screening, mechanistic studies, pharmacokinetics [6] [3] | OECD TGs for specific endpoints; increasing acceptance in drug development [1] [7] |

| In Silico Tools | QSAR, read-across, PBPK models, AI/ML algorithms [2] [3] | Toxicity prediction, priority setting, chemical categorization [2] | EPA list of accepted methods; OECD QSAR Toolbox [8] [2] |

| Omics Technologies | Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics [3] | Biomarker discovery, mechanism of action, pathway analysis [3] | Emerging frameworks (OECD Omics Reporting Framework) [8] |

| In Chemico Assays | Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay (DPRA) [3] | Skin sensitization potential [3] | OECD TG 442C [3] |

| Integrated Approaches | Defined Approaches (DAs), IATA, AOP frameworks [1] [3] | Comprehensive safety assessment, weight-of-evidence [1] | OECD TGs 467 (skin sensitization), 497 (eye irritation) [1] |

The Regulatory Toolbox Concept

The true power of NAMs lies in their integration as a cohesive toolbox rather than as standalone methods. This integrated approach allows researchers and regulators to select appropriate combinations of methods based on specific testing needs and contexts of use [1] [3]. For example, a Defined Approach (DA) represents a specific combination of data sources (e.g., in silico, in chemico, and/or in vitro data) with fixed data interpretation procedures, which has successfully facilitated the use of NAMs-based approaches within regulatory contexts for endpoints like serious eye damage/eye irritation and skin sensitization [1]. These DAs have been outlined within their own OECD test guidelines (TGs 467 and 497) and are now widely used and referenced in many regulations worldwide [1].

The toolbox concept extends beyond simple test replacement to encompass a fundamental reimagining of safety assessment. As described in the US National Academy of Science's 2007 report "Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century," the vision was not merely to replace animal tests but to approach toxicological safety assessment in a new way, through consideration of exposure and mechanistic information using a range of in vitro and computational models [1]. This approach acknowledges that NAMs may never be wholly representative of every aspect of organism-level adverse response, but instead provide a human-focused and conceptually different way to assess human hazard and risk [1].

Quantitative Performance Assessment of NAMs

Comparative Performance Metrics

The transition to NAMs requires careful evaluation of their performance relative to traditional methods. The following table summarizes key comparative data that informs current understanding of NAMs reliability and applicability.

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of NAMs Performance and Validation

| Assessment Area | Traditional Animal Models | NAM-based Approaches | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Predictivity | Rodents: 40-65% true positive human toxicity predictivity rate [1] | Improved relevance via human biology; combination approaches outperform animal tests for specific endpoints [1] | For skin sensitization, a combination of three in vitro approaches outperformed the Local Lymph Node Assay (LLNA) in specificity [1] |

| Validation Status | OECD test guidelines established for decades | OECD TGs available for defined approaches (e.g., TG 467, 497); others in development [1] | Successful case studies for crop protection products Captan and Folpet using 18 in vitro studies [1] |

| Uncertainty Characterization | Established historical uncertainty factors; limited quantitative assessment [5] | Emerging frameworks for quantitative uncertainty analysis [5] | CEFIC LRI Project AIMT12 developing case examples for quantitative uncertainty analysis of NAMs [5] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Default requirement under many regulatory frameworks [8] | Conditional acceptance based on scientific justification and context of use [7] | FDA Modernization Act 2.0; EPA Strategic Plan to Promote Alternative Test Methods [8] [2] |

Uncertainty Quantification in NAMs

A critical aspect of regulatory acceptance involves understanding and quantifying uncertainties associated with NAM-based hazard characterization [5]. Traditional risk assessment has established approaches for dealing with uncertainties in animal studies, but similar frameworks for NAMs are still evolving. Initiatives like the CEFIC LRI Project AIMT12 aim to address this gap by performing probabilistic and deterministic quantitative uncertainty analyses for both traditional and NAM-based hazard characterization [5]. This project seeks to deliver transparent, balanced, and quantitative evidence about uncertainties in the derivation of safe exposure levels based on animal data versus NAM-derived data, recognizing that there will be methodology and data situations where NAM-based assessment bears less uncertainty, and other situations where animal-data based assessments are preferable [5].

The uncertainty analysis extends beyond technical performance to encompass broader validation considerations. For complex endpoints and systemic toxicity, it is increasingly recognized that benchmarking NAMs against animal data may not be scientifically appropriate, given that commonly used test species like rodents have documented limitations in their human toxicity predictivity [1]. This recognition is driving the development of alternative validation frameworks that focus on human biological relevance rather than correlation with animal data [1] [9].

Experimental Protocols for Ecotoxicology Applications

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Susceptibility Extrapolation Using SeqAPASS

Purpose: To predict chemical susceptibility across multiple ecological species, particularly for endangered species where traditional testing is impractical or unethical [2].

Principle: The Sequence Alignment to Predict Across Species Susceptibility (SeqAPASS) tool enables extrapolation of toxicity information from data-rich model organisms to thousands of other non-target species by comparing protein sequence similarity and structural features of key molecular initiating events [2].

Materials:

- SeqAPASS online platform (publicly available)

- Protein sequence data for species of interest

- Chemical-specific molecular target information

- Taxonomic information for ecological relevance assessment

Procedure:

- Identify Molecular Target: Determine the primary protein target associated with the chemical's toxicity mechanism (e.g., acetylcholinesterase for organophosphates).

- Input Reference Sequences: Upload protein sequences from well-characterized model organisms (e.g., fathead minnow, zebrafish) known to be sensitive to the chemical.

- Define Comparison Thresholds: Establish sequence similarity thresholds based on known structure-activity relationships for the target.

- Run Cross-Species Analysis: Execute the SeqAPASS algorithm to compare sequence similarity across multiple species.

- Interpret Susceptibility Predictions: Classify species as susceptible or non-susceptible based on sequence conservation at critical residues.

- Integrate with Taxonomic Information: Contextualize predictions within ecological frameworks to prioritize risk assessment.

Validation: Compare predictions with available empirical toxicity data to assess accuracy and refine threshold settings.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Toxicokinetics Using HTTK

Purpose: To estimate tissue concentrations and administered equivalent doses for ecological risk assessment using in vitro toxicokinetic data [2].

Principle: The high-throughput toxicokinetics (HTTK) approach uses in vitro data on plasma protein binding and hepatic clearance to parameterize physiologically based toxicokinetic models that can predict internal dose metrics across species [2].

Materials:

- HTTK R package (open-source)

- In vitro toxicokinetic data (Fup, CLint)

- Physiological parameters for relevant species

- Chemical property data (log P, pKa, molecular weight)

Procedure:

- Generate In Vitro TK Parameters:

- Measure fraction unbound in plasma (Fup) using rapid equilibrium dialysis

- Determine intrinsic clearance (CLint) in hepatocytes or microsomes

- Parameterize PBTK Model:

- Load chemical-specific data into HTTK package

- Select appropriate species-specific physiological model

- Run forward dosimetry to predict tissue concentrations from exposure doses

- Perform Reverse Dosimetry:

- Input bioactive concentrations from in vitro assays

- Calculate administered equivalent doses (AEDs) that would produce bioactive internal concentrations

- Apply Uncertainty Analysis:

- Quantify parameter uncertainty using Monte Carlo simulations

- Compare uncertainty distributions with traditional assessment factors

Application: This protocol enables derivation of point-of-departure estimates for risk assessment based on bioactivity data from high-throughput screening assays [2].

Integrated Workflow for NAMs in Ecotoxicology

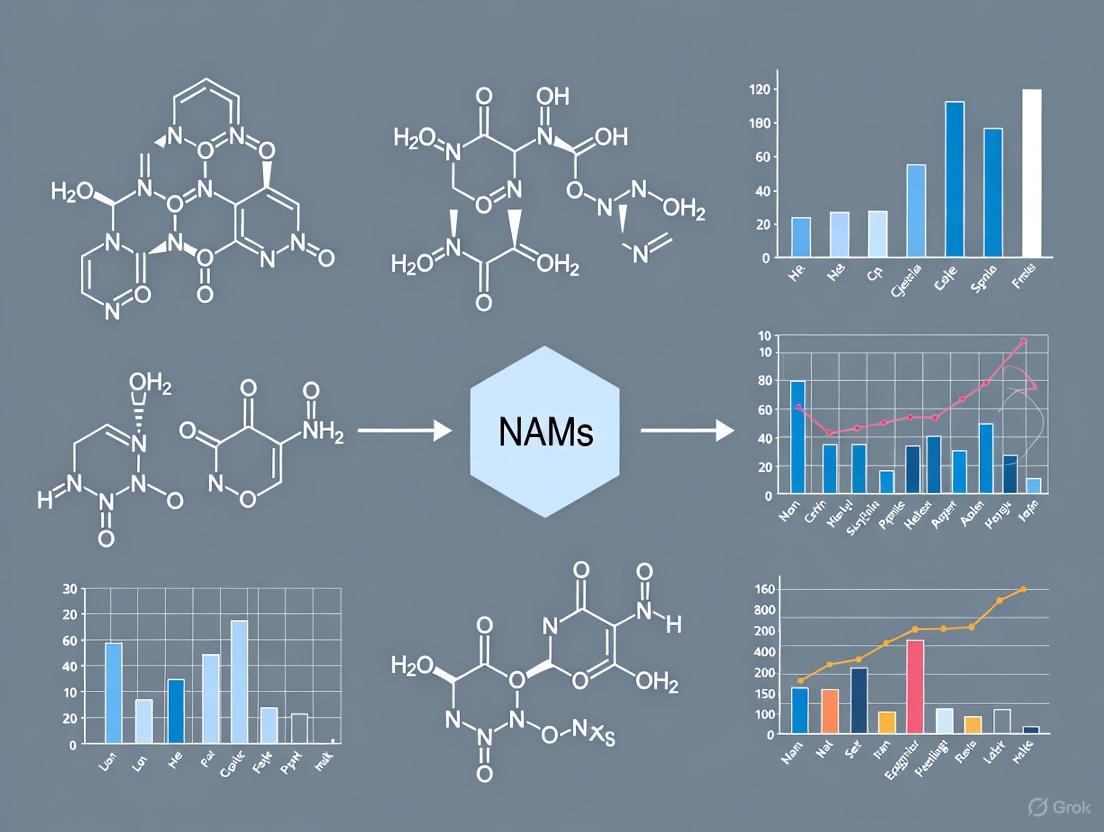

The effective application of NAMs in ecotoxicology requires systematic integration of multiple data sources and assessment tools. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points and method applications in an ecological risk assessment context.

Diagram 1: Integrated NAM Workflow for Ecotoxicology

This integrated workflow demonstrates how different NAM tools contribute to a comprehensive ecological risk assessment, moving from chemical characterization through to risk management decisions while explicitly considering cross-species susceptibilities and exposure scenarios.

Essential Research Toolkit for NAMs Implementation

Successful implementation of NAMs in ecotoxicology research requires access to specialized tools and databases. The following table catalogs essential resources available to researchers.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for NAMs in Ecotoxicology

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [2] | Database | Centralized source for chemical, hazard, bioactivity, and exposure data | Public online access |

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase [2] | Database | Single chemical toxicity data for aquatic life, terrestrial plants, and wildlife | Public online access |

| SeqAPASS [2] | Computational Tool | Cross-species susceptibility extrapolation based on protein sequence similarity | Public online access |

| HTTK R Package [2] | Computational Tool | High-throughput toxicokinetic modeling for forward and reverse dosimetry | Open-source R package |

| ToxCast/Tox21 [2] | Database | High-throughput screening bioactivity data for thousands of chemicals | Public access via EPA |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Computational Tool | Chemical categorization and read-across based on structural and mechanistic similarity | Freely available to researchers |

| General Read-Across (GenRA) [2] | Computational Tool | Read-across predictions using chemical similarity and toxicological data | Available via CompTox Dashboard |

| Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Wiki | Knowledge Base | Structured framework for mechanistic toxicity information | Public online access |

| SDR-04 | SDR-04, MF:C19H16N4O2, MW:332.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| cis,trans-Germacrone | cis,trans-Germacrone, MF:C15H22O, MW:218.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Quality Assurance Considerations

Implementation of these tools requires careful attention to quality assurance and context of use definition [7]. Researchers should document the specific versions of databases and software used, as these resources are frequently updated. Additionally, understanding the limitations and applicability domains of each tool is essential for appropriate interpretation of results. Regulatory acceptance of NAM data depends heavily on transparent documentation of methodologies and validation of approaches for specific assessment contexts [7] [9].

For ecotoxicology applications, the species relevance of models and assays must be carefully considered, as human-focused NAMs may require adaptation or additional validation for ecological species [2]. Tools like SeqAPASS specifically address this challenge by enabling cross-species extrapolation, but still require grounding in empirical data when available [2].

Regulatory Pathway and Context of Use Definition

Establishing Regulatory Confidence

The regulatory acceptance of NAMs follows defined pathways that emphasize scientific validity and fit-for-purpose application [7]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) outlines key considerations for regulatory acceptance, including the availability of a defined test methodology, description of the proposed context of use, establishment of relevance within that context, and demonstration of reliability and robustness [7]. Similar frameworks exist at the US FDA and EPA, with increasing coordination between agencies to harmonize expectations [4] [2].

A critical concept in regulatory acceptance is the "context of use" (COU), which describes the specific circumstances under which a NAM is applied in the assessment of chemicals or medicines [7] [6]. Defining the COU with precision allows regulators to evaluate whether the scientific evidence supports use of the NAM for that specific application. The COU encompasses the types of decisions the method will inform, the specific endpoints it measures, and its position within a broader testing strategy (e.g., as a replacement for an existing test versus part of a weight-of-evidence approach) [7].

Pathways for Regulatory Engagement

Regulatory agencies have established specific pathways for developers to engage on NAM qualification and acceptance:

- Briefing Meetings: Informal discussions through platforms like EMA's Innovation Task Force provide early dialogue on NAM development and regulatory readiness [7].

- Scientific Advice Procedures: Opportunity to ask regulatory agencies specific questions about including NAM data in future regulatory submissions [7].

- Qualification Procedures: Formal process for demonstrating the utility and regulatory relevance of a NAM for a specific context of use, potentially leading to qualification opinions [7].

- Voluntary Data Submissions: "Safe harbour" approach where developers can submit NAM data for regulatory evaluation without immediate regulatory consequences [7].

These pathways facilitate iterative development and regulatory feedback, building confidence in NAMs through transparent scientific exchange. For ecotoxicology applications, engagement with both environmental and health authorities may be necessary, depending on the regulatory context and intended application of the data.

The evolution of NAMs from simple non-animal alternatives to sophisticated regulatory tools represents a fundamental transformation in safety assessment science. This transition is driven by the convergence of ethical imperatives (3Rs), scientific advances in human biology modeling, and practical needs for more efficient and predictive assessment methods [1] [4] [3]. The future of NAMs in ecotoxicology and broader chemical safety assessment lies in their continued integration into standardized workflows, supported by robust validation frameworks and clear regulatory pathways [9] [2].

The ultimate goal is not one-for-one replacement of animal tests, but rather the establishment of a new paradigm that leverages human-relevant biology and computational approaches to better protect human health and ecological systems [1]. Achieving this vision requires ongoing collaboration between researchers, regulators, and industry stakeholders to build confidence in NAM-based approaches and address remaining scientific and technical challenges [1] [9]. As these efforts advance, NAMs will increasingly become the first choice for safety assessment, fulfilling their potential as a comprehensive suite of regulatory tools that provide more relevant, efficient, and predictive protection of public health and the environment.

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) represent a transformative shift in toxicology and ecotoxicology, defined as any technology, methodology, approach, or combination that can provide information on chemical hazard and risk assessment while avoiding traditional animal testing [10]. These methodologies include in silico (computational), in chemico (abiotic chemical reactivity measures), and in vitro (cell-based) assays, as well as advanced approaches employing omics technologies and testing on non-protected species or specific life stages [10] [11]. The fundamental premise of NAMs is not merely to replace animal tests but to enable a more rapid and effective prioritization of chemicals through human-relevant, mechanism-based data [10] [1].

The transition to NAMs is driven by a powerful convergence of scientific, ethical, and economic imperatives. Regulatory agencies worldwide, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), are actively promoting their adoption to streamline chemical hazard assessment while addressing growing concerns about animal testing [10] [7]. This application note examines these driving forces within the context of ecotoxicology research and drug development, providing structured data comparisons, experimental protocols, and visualizations to guide researchers in implementing NAMs.

Quantitative Analysis of NAMs Adoption Drivers

Comparative Analysis of Testing Approaches

Table 1: Economic and Efficiency Comparison of Testing Methods

| Parameter | Traditional Animal Testing | NAMs-Based Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Testing Duration | Months to years [12] | Days to weeks [12] |

| Cost per Compound | High (significant resources for animal care and facilities) [12] | Low to moderate (reduced infrastructure needs) [12] |

| Throughput Capacity | Low (limited number of compounds simultaneously) [12] | High (screens thousands of chemicals across hundreds of targets) [12] |

| Human Relevance | 40-65% predictivity for human toxicity [1] | Higher potential for human-relevant mechanisms [1] [13] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established but with known limitations [1] | Growing, with specific validated approaches (e.g., OECD TG 467, 497) [1] |

Regulatory Adoption Metrics

Table 2: Regulatory Landscape for NAMs Implementation

| Regulatory Body | Key Policy/Initiative | Implementation Status | Impact on Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. EPA | ToxCast, CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [14] | Active use for chemical prioritization and risk assessment [8] | Reducing vertebrate animal testing requirements [8] |

| U.S. FDA | FDA Modernization Act 2.0/3.0, 2025 Roadmap [15] [13] | Pilot programs for monoclonal antibodies; phased implementation [15] | Permits alternative methods for drug safety and efficacy [13] |

| European EMA | Innovation Task Force, Qualification Procedures [7] | Case-by-case acceptance via scientific advice and qualification [7] | Facilitates 3Rs principles in medicine development [7] |

| International OECD | Defined Approaches (DAs) guidelines (e.g., TG 467, 497) [1] | Standardized test guidelines for specific endpoints [1] | Enables global harmonization of NAMs for regulatory use [1] |

Scientific Imperatives: Enhanced Relevance and Predictive Capacity

Mechanisms and Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs)

NAMs enable a mechanism-based understanding of toxicity through Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs) that link molecular initiating events to adverse outcomes at organism and population levels [8]. This framework shifts toxicology from observational endpoints in non-human species to human-relevant pathway-based assessments [1]. The EPA's ToxCast program utilizes high-throughput NAMs to generate mechanism-based data that inform AOPs, allowing regulatory decisions to be grounded in biologically plausible and empirically supported pathways [8].

The scientific case for NAMs is strengthened by the limited predictivity of traditional animal models. Rodent studies, commonly used as toxicology "gold standards," show only 40-65% true positive predictivity for human toxicity [1]. Furthermore, more than 90% of drugs successful in animal trials fail to gain FDA approval, highlighting fundamental translational challenges [13]. These limitations stem from species-specific differences in physiology, metabolism, and genetic diversity that NAMs specifically address through human cell-based systems and computational models [13].

Protocol: Implementing Integrated Testing Strategies for Bioaccumulation Assessment

Application: This protocol outlines an Integrated Approach to Testing and Assessment (IATA) for bioaccumulation potential of chemicals in aquatic and terrestrial environments, suitable for regulatory decision-making [16].

Materials and Equipment:

- In silico tools: Chemical Structure Drawing Software (e.g., ChemDraw), QSAR Toolkits (e.g., OECD QSAR Toolbox)

- In vitro systems: Cultured hepatocyte cells (rainbow trout or human origin), relevant cell culture equipment

- Analytical instruments: High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system, mass spectrometer

- Test chemical: Reference compounds with known bioaccumulation factors (BAFs)

Procedure:

- Chemical Characterization (Day 1-2):

- Obtain/draw precise chemical structure

- Calculate log P (octanol-water partition coefficient) using QSAR tools

- Screen for structural alerts associated with persistence and bioaccumulation

In Vitro Hepatic Clearance Assay (Day 3-7):

- Plate hepatocyte cells (species-relevant) in 24-well plates at 1×10ⶠcells/well

- Expose cells to test chemical at 1-10 µM concentration (depending on solubility)

- Collect media samples at 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 hours

- Analyze chemical concentration using HPLC-MS/MS

- Calculate intrinsic clearance rate

Data Integration and Weight-of-Evidence Assessment (Day 8-10):

- Compile data from in silico predictions and in vitro assays

- Apply decision criteria: log P > 4.0 + low hepatic clearance = high bioaccumulation potential

- Compare results to existing data on reference compounds

- Prepare assessment report with clear documentation of all data sources and interpretation criteria

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For poorly soluble compounds, consider alternative dosing strategies (e.g., passive dosing)

- Include positive (known bioaccumulative) and negative controls in all assays

- Verify metabolic competence of hepatocyte preparations with reference compounds

Ethical and Legal Imperatives: The 3Rs Framework

Regulatory Drivers and Legal Mandates

The ethical imperative for NAMs centers on the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement of animal testing) [10] [1]. This ethical framework has been incorporated into legal mandates, most notably the U.S. Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which explicitly instructs the EPA to reduce and replace vertebrate animal testing "to the extent practicable and scientifically justified" [8]. The Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act further strengthens this mandate by encouraging the development and rapid adoption of NAMs [8].

Internationally, regulatory agencies have established formal pathways for NAMs acceptance. The EMA offers multiple interaction types for developers, including briefing meetings, scientific advice, and qualification procedures [7]. The FDA's 2025 "Roadmap to reducing animal testing in preclinical safety studies" outlines a stepwise approach to make animal studies "the exception rather than the rule," particularly for well-characterized drug classes like monoclonal antibodies [15] [13]. This evolving regulatory landscape represents a shift from considering NAMs as optional alternatives to recognizing them as scientifically preferred approaches for many applications [8].

Visualization: Regulatory Acceptance Pathway for NAMs

Diagram 1: Roadmap for regulatory acceptance of NAMs, illustrating the pathway from method development to full regulatory adoption through defined processes including early dialogue and validation [7].

Economic Imperatives: Efficiency and Return on Investment

Cost-Benefit Analysis of NAMs Implementation

The economic case for NAMs stems from their ability to deliver significant cost savings and faster results compared to traditional animal testing [12]. Animal studies require substantial financial resources for animal care, facility maintenance, and compliance with regulatory standards, whereas many NAMs can be conducted with lower infrastructure investment and shorter timeframes [12]. The National Academies' 2017 report found that integrating NAMs into chemical risk assessments could significantly reduce both cost and time while improving human relevance [12].

Programs like the EPA's ToxCast and the interagency Tox21 initiative demonstrate the economic advantage of NAMs, screening thousands of chemicals across hundreds of biological targets within months rather than years [12]. This accelerated timeline benefits regulatory agencies managing large chemical inventories and industries seeking faster development cycles. For pharmaceutical companies, early toxicity identification through NAMs can prevent costly late-stage failures, optimizing research and development expenditures [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Core Research Tools for NAMs Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Toxicology | CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, TEST, httk R Package [14] | Chemical prioritization, toxicokinetic modeling, toxicity prediction | EPA-recognized for specific applications [8] [14] |

| In Vitro Bioactivity | ToxCast, invitroDB [14] | High-throughput screening for bioactivity and mechanism elucidation | Used in EPA chemical evaluations [8] |

| Ecotoxicology Tools | SeqAPASS, ECOTOX, Web-ICE [14] | Species extrapolation, ecotoxicological data compilation, cross-species prediction | Applied in ecological risk assessment [14] |

| Microphysiological Systems | Organ-on-chip, 3D organoids [15] [13] | Human-relevant tissue modeling, disease pathogenesis studies | Case-by-case acceptance; pilot programs [15] [13] |

| Exposure Science | SHEDS-HT, ChemExpo [14] | Exposure prediction, chemical use analysis, risk context | Supporting chemical prioritization [14] |

| Crenatoside | Crenatoside, CAS:61276-16-2, MF:C29H34O15, MW:622.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Olivanic acid | Olivanic Acid|Carbapenem Antibiotic|For Research | Olivanic acid is a beta-lactamase inhibitor and carbapenem antibiotic for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Integrated Experimental Protocol: NAMs for Systemic Toxicity Assessment

Comprehensive Testing Strategy

Application: This protocol describes a defined approach for assessing potential systemic toxicity of chemicals using an integrated in silico and in vitro strategy, applicable for chemical prioritization and risk assessment [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Computational resources: Access to CompTox Chemicals Dashboard and QSAR toolkits

- Cell culture: Hepatocyte cells (HepG2 or primary human hepatocytes), endothelial cells (HUVEC), neuronal cells (SH-SY5Y)

- Assay kits: Cell viability/toxicity (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo), caspase-3/7 activity assay, high-content screening reagents

- Equipment: Cell culture facility, plate reader, high-content imaging system, HPLC-MS/MS

Procedure:

- Tier 1: In Silico Profiling (Week 1):

- Input chemical structure into CompTox Chemicals Dashboard

- Retrieve existing ToxCast/Tox21 bioactivity data if available

- Run QSAR models for key toxicity endpoints (hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity)

- Calculate physicochemical properties (log P, molecular weight)

- Apply structural alerts for known toxicophores

Tier 2: In Vitro Bioactivity Screening (Week 2-3):

- Plate relevant cell types in 96-well plates

- Prepare 8-point concentration series of test chemical (typically 1 nM - 100 µM)

- Expose cells for 24 and 72 hours

- Assess multiple endpoints:

- Cell viability (MTT assay)

- Mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1 staining)

- Oxidative stress (DCFDA assay)

- High-content imaging for nuclear morphology and cell density

- Include appropriate positive and vehicle controls

Tier 3: Toxicokinetic Assessment (Week 4):

- Use hepatic clearance data from in vitro assays

- Apply httk R package for toxicokinetic modeling

- Calculate predicted human plasma concentrations

- Derive bioactivity-exposure ratios (BERs) for risk-based prioritization

Data Integration and Reporting (Week 5):

- Compile all data streams using structured templates

- Apply adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework where possible

- Compare results to existing animal data for validation

- Prepare comprehensive testing report with uncertainty assessment

Validation Considerations:

- Benchmark against known reference chemicals with extensive in vivo data

- Establish laboratory-specific historical control ranges

- Document all protocol deviations and data processing steps

Visualization: Integrated NAMs Testing Strategy for Systemic Toxicity

Diagram 2: Integrated NAMs testing strategy illustrating the sequential approach from in silico profiling to risk-based prioritization for systemic toxicity assessment [1] [14].

The adoption of New Approach Methodologies represents a paradigm shift in toxicology and ecotoxicology, driven by compelling scientific, ethical, and economic imperatives. Scientifically, NAMs offer more human-relevant, mechanism-based insights compared to traditional animal models with their known limitations in predicting human responses [1] [13]. Ethically, they advance the 3Rs principles through legislative mandates like TSCA and the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 [8]. Economically, they provide faster, more cost-effective testing strategies that benefit both regulatory agencies and industry [12].

The successful implementation of NAMs requires continued validation, standardization, and regulatory harmonization [1]. International organizations like the OECD are addressing these needs through detailed guidance on models and reporting frameworks [8]. As confidence in these methods grows, their application will expand to address more complex toxicity endpoints, further reducing reliance on animal testing while enhancing the protection of human health and environmental ecosystems [1].

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) represent a transformative suite of tools and frameworks designed to modernize toxicology and safety assessment. These methodologies provide more human-relevant, ethical, and mechanistically informed approaches for evaluating chemical hazards, aligning with the global trend toward reducing reliance on traditional animal testing [3]. In ecotoxicology, NAMs have gained significant momentum, driven by ethical considerations, regulatory needs under chemical regulations like REACH, and advancements in technology [17]. The core components of NAMs include in vitro (cell-based) systems, in silico (computational) models, and omics technologies, which can be used independently or integrated within strategic frameworks like Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA) [3]. These methodologies enable rapid screening and prioritization of chemical hazards, categorization by modes of action, and provide mechanistic data for predicting adverse outcomes, thereby enhancing environmental hazard assessment while reducing animal testing [17].

In Vitro Technologies: Cellular Systems for Toxicity Assessment

In vitro technologies utilize cultured cells or tissues to assess biological responses to environmental contaminants under controlled conditions. These systems range from simple two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures to more complex three-dimensional (3D) models that better mimic tissue-level physiology [18] [3].

Representative Cell Lines and Their Applications

Cell-based assays form the foundation of in vitro toxicology, providing models for studying organ-specific toxicity. The table below summarizes key cell lines used in environmental toxicology research.

Table 1: Characteristics and applications of common cell lines in environmental toxicology

| Cell Line | Cell Type | Applications in Toxicology | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| HepG2 | Hepatoblastoma [18] | Hepatotoxicity, metabolic disorders, oxidative stress [18] | Rapid proliferation; retains metabolic and oxidative stress pathways [18] |

| HepaRG | Hepatocellular carcinoma [18] | Hepatic transport, metabolic dysfunction, genotoxicity [18] | Maintains protein metabolism and transport capabilities [18] |

| A549 | Lung carcinoma [18] | Respiratory toxicity studies [18] | Model for lung epithelium response to inhaled pollutants |

| SH-SY5Y | Human neuroblastoma [18] | Neurotoxicity testing [18] | Differentiates into neuron-like cells; model for nervous system |

| RTgill-W1 | Rainbow trout gill epithelium [19] [17] | Alternative to acute fish lethality testing; ecological risk assessment [19] [17] | Fish cell line; used in high-throughput screening for ecotoxicology |

Advanced In Vitro Models: From 2D to 3D Systems

Technological advances have enabled the development of more physiologically relevant models:

- Stem Cell-Derived Models: Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), provide a versatile platform for generating human-relevant toxicological models. These cells can differentiate into various cell types, offering species-relevant and predictive options for modern environmental toxicology [18].

- Three-Dimensional (3D) Models: 3D cell cultures, such as spheroids, organoids, and Organ-on-a-Chip systems, offer significant advantages over traditional 2D cultures by recapitulating tissue-specific architecture, cell-cell interactions, and metabolic functions more accurately. These innovative models present a promising horizon for environmental toxicology by providing more organ-like responses [18] [3].

- Organ-on-a-Chip Systems: These microengineered devices mimic organ-level functions by incorporating fluid flow, mechanical forces, and tissue-tissue interfaces. They serve as a powerful bridge between simple cell culture and whole-organism physiology, enabling dynamic studies of toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and mechanisms of action [3].

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Cytotoxicity Screening in RTgill-W1 Cells

Purpose: To assess chemical cytotoxicity using a fish gill cell line as an alternative to the in vivo acute fish lethality test (OECD Test Guideline 203) [19] [17].

Materials:

- RTgill-W1 cell line: Derived from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) gill epithelium [19].

- Growth medium: Appropriate medium such as L-15 supplemented with fetal bovine serum [17].

- Cell culture plastics: 96-well or 384-well plates for miniaturized, high-throughput format [19].

- Test chemicals: Prepared in suitable solvent with solvent controls.

- Detection reagents:

- Cell viability indicators: AlamarBlue, CFDA-AM, or propidium iodide for plate reader-based assays [19].

- Cell Painting reagents: Alexa Fluor-conjugated phalloidin (F-actin), Hoechst 33342 (nuclei), SYTO 14 (nucleoli), concanavalin-A (endoplasmic reticulum), and wheat germ agglutinin (Golgi and plasma membrane) for morphological profiling [19].

- Equipment: Plate reader, high-content imaging microscope, automated liquid handling systems.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed RTgill-W1 cells in 96-well or 384-well plates at optimal density (e.g., 10,000 cells/well for 96-well format) and culture until ~80% confluent [19].

- Chemical Exposure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of test chemicals in exposure medium.

- Expose cells to chemicals for 24-48 hours, including solvent and positive controls.

- Apply an in vitro disposition (IVD) model to account for chemical sorption to plastic and cells, predicting freely dissolved concentrations [19].

- Endpoint Measurement:

- Option A - Plate reader viability: Incubate with cell viability indicator (e.g., AlamarBlue for metabolism, CFDA-AM for membrane integrity) and measure fluorescence [19].

- Option B - Cell Painting assay:

- Fix cells with paraformaldehyde.

- Stain with Cell Painting cocktail (phalloidin, Hoechst, SYTO 14, concanavalin-A, WGA).

- Image using high-content microscope (5 channels/well).

- Extract morphological features (~1,500 parameters/cell) for phenotypic profiling [19].

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate potencies (e.g., PC50 for viability, PAC for phenotype alteration).

- Compare bioactivity calls between viability assays and Cell Painting.

- Apply IVD modeling to adjust for chemical bioavailability [19].

Data Interpretation: The Cell Painting assay typically detects more bioactive chemicals at lower concentrations than viability assays. Adjusted PACs (Phenotype Altering Concentrations) using IVD modeling should be compared to in vivo fish toxicity data. For the 65 chemicals where comparison was possible, 59% of adjusted in vitro PACs were within one order of magnitude of in vivo lethal concentrations, and in vitro PACs were protective for 73% of chemicals [19].

High-Throughput Cytotoxicity Screening Workflow

In Silico Technologies: Computational Predictive Modeling

In silico approaches use computational methods to predict chemical toxicity based on structural properties and existing data, enabling rapid screening of large chemical libraries.

Core In Silico Methodologies

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSARs): These models predict a chemical's biological activity and toxicity based on its molecular structure and physicochemical properties. QSARs are particularly valuable for prioritizing chemicals for further testing and filling data gaps without additional experimentation [3].

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Models: PBPK modeling simulates the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of chemicals in organisms, predicting target organ concentrations and internal doses responsible for toxicity [3].

- Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs): AOPs provide conceptual frameworks that organize existing knowledge about toxic mechanisms, linking molecular initiating events through key cellular and organ-level responses to adverse outcomes at individual or population levels. They facilitate the use of in vitro and in silico data for predicting in vivo toxicity [20] [3].

- Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence: These approaches leverage large toxicological datasets to identify patterns and build predictive models of toxicity across diverse chemical classes, enhancing the ability to screen thousands of compounds computationally before laboratory testing [3].

Experimental Protocol: Development and Application of QSAR Models

Purpose: To predict ecotoxicological hazards of chemicals using quantitative structure-activity relationships.

Materials:

- Chemical structures: SMILES notations or molecular descriptors for compounds of interest.

- Toxicity data: Experimental endpoints (e.g., LC50, EC50) from in vivo or in vitro studies for model training.

- Software tools:

- QSAR development: DRAGON, PaDEL-Descriptor for calculating molecular descriptors; WEKA, R or Python with scikit-learn for model building.

- Validation tools: OECD QSAR Toolbox, VEGA platforms.

- Computational resources: Standard computer workstation; high-performance computing for large datasets.

Procedure:

- Data Collection:

- Compile chemical structures and corresponding experimental toxicity data for training set.

- Apply strict criteria for data quality and consistency (e.g., standardized test protocols, uniform endpoint definitions).

- Descriptor Calculation:

- Compute molecular descriptors representing structural and physicochemical properties (e.g., logP, molecular weight, topological indices, electronic parameters).

- Select relevant descriptors using feature selection methods to avoid overfitting.

- Model Building:

- Split data into training (~80%) and test sets (~20%).

- Apply modeling algorithms (e.g., multiple linear regression, partial least squares, random forest, support vector machines).

- Optimize model parameters using cross-validation.

- Model Validation:

- Assess internal performance using training set data (cross-validation).

- Evaluate external predictivity using test set data.

- Apply OECD validation principles: defined endpoint, unambiguous algorithm, defined domain of applicability, appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit and predictivity, mechanistic interpretation if possible.

- Model Application:

- Predict toxicity for new chemicals within the defined applicability domain.

- Quantify uncertainty for predictions.

- Use results for chemical prioritization and risk assessment.

Data Interpretation: QSAR predictions should be interpreted in the context of the model's applicability domain and performance metrics. Predictions for chemicals structurally similar to training set compounds are more reliable. QSAR results can be combined with other NAMs data in weight-of-evidence approaches [21] [3].

Omics Technologies: Comprehensive Molecular Profiling

Omics technologies enable comprehensive analysis of biological molecules, providing detailed mechanistic insights into toxicological responses at molecular level.

Major Omics Approaches in Ecotoxicology

- Metabolomics: The comprehensive analysis of metabolites in a biological system under specific conditions. It provides detailed information about the biochemical/physiological status and changes caused by chemicals, making it closely related to classical knowledge of disturbed biochemical pathways [20] [22].

- Transcriptomics: Profiling of gene expression changes in response to chemical exposure, identifying differentially expressed genes and affected pathways.

- Proteomics: Large-scale study of protein expression, modifications, and interactions, connecting genomic information with functional cellular responses.

- Integrative Omics: Combining multiple omics datasets to build comprehensive models of toxicological mechanisms across biological organization levels.

Experimental Protocol: Metabolomics for Mechanistic Toxicology

Purpose: To identify metabolic changes induced by chemical exposure and elucidate mechanisms of toxicity.

Materials:

- Biological samples: In vitro systems (cells, tissues), body fluids (plasma, urine), or tissues from exposed organisms.

- Sample preparation: Solvents (methanol, acetonitrile, chloroform), buffers, internal standards.

- Analytical instrumentation:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): High-resolution mass spectrometer coupled to UHPLC system.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: High-field NMR spectrometer.

- Data analysis software: XCMS, MetaboAnalyst, NMR processing software, statistical analysis tools.

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- Include appropriate controls, replicates (minimum n=5-6 for in vivo studies), and quality control samples (pooled quality control samples).

- Consider time-course designs to capture dynamic responses.

- Sample Preparation:

- Quench metabolism rapidly (e.g., liquid nitrogen for cells/tissues).

- Extract metabolites using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol:water:chloroform).

- Add internal standards for quantification.

- For LC-MS: Centrifuge, collect supernatant, evaporate, and reconstitute in MS-compatible solvent.

- For NMR: Prepare samples in deuterated buffer.

- Data Acquisition:

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Separate metabolites using reverse-phase or HILIC chromatography.

- Acquire data in full-scan mode with positive and negative electrospray ionization.

- Include quality control samples throughout sequence to monitor instrument performance.

- NMR Analysis:

- Acquire 1D 1H NMR spectra with water suppression.

- Optional: 2D NMR for metabolite identification.

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Data Processing:

- Convert raw data to analyzable formats (e.g., mzML for MS, JCAMP-DX for NMR).

- Perform peak picking, alignment, and integration.

- Normalize data to correct for variations (e.g., probabilistic quotient normalization).

- Identify metabolites using authentic standards, databases (HMDB, METLIN), and spectral libraries.

- Statistical Analysis and Interpretation:

- Apply multivariate statistics (PCA, PLS-DA) to identify patterns.

- Use univariate statistics (t-tests, ANOVA) to find significantly altered metabolites.

- Perform pathway analysis (KEGG, MetaboAnalyst) to identify disturbed metabolic pathways.

- Integrate with other omics data if available.

Data Interpretation: Metabolomics data should be interpreted in the context of known toxic mechanisms and pathways. The relatively small number of metabolites (hundreds to thousands) compared to transcripts or proteins facilitates the identification of meaningful changes associated with toxic effects. Metabolite changes often reflect downstream consequences of molecular initiating events, making metabolomics particularly valuable for connecting molecular changes to phenotypic outcomes [20] [22].

Metabolomics Workflow for Mechanistic Toxicology

Integrated Approaches: Combining NAMs for Enhanced Assessment

The true power of New Approach Methodologies emerges when in vitro, in silico, and omics approaches are strategically combined within integrated testing strategies.

Framework for NAMs Integration

Table 2: Strategies for integrating NAMs components in ecotoxicological assessment

| Integration Approach | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA) | Structured frameworks that combine multiple data sources for regulatory decision-making [3] | Sequential testing strategy starting with QSAR predictions, followed by in vitro screening, and targeted in vivo testing if needed |

| Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs) | Conceptual frameworks linking molecular initiating events to adverse outcomes [20] [3] | Using transcriptomics to identify molecular initiating events and in vitro assays to characterize key events in an AOP network |

| Bioactivity-Exposure Ratio Assessment | Comparing bioactivity concentrations from in vitro assays to estimated exposure concentrations [21] | Prioritizing chemicals with highest bioactivity-exposure ratios for further testing |

| IVIVE (In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation) | Computational models to extrapolate in vitro effective concentrations to in vivo doses [19] [17] | Applying physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling to convert in vitro AC50 values to predicted in vivo doses |

Research Reagent Solutions for NAMs Implementation

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for NAMs implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Culture Systems | Generating human-relevant toxicology models [18] | hESCs cultured on vitronectin with mTesR plus medium; hiPSCs with StemFlex or E8 medium [18] |

| Cell Viability Assays | Measuring cytotoxicity and cell health [19] | AlamarBlue (metabolic activity), CFDA-AM (membrane integrity), propidium iodide (cell death) |

| Cell Painting Cocktail | Multiplexed morphological profiling [19] | Alexa Fluor-conjugated phalloidin, Hoechst 33342, SYTO 14, concanavalin-A, wheat germ agglutinin |

| Molecular Descriptors Software | Calculating chemical features for QSAR [3] | DRAGON, PaDEL-Descriptor; generating 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors |

| Metabolomics Standards | Metabolite identification and quantification [22] | Stable isotope-labeled internal standards; reference compounds for targeted analysis |

| Mass Spectrometry Systems | High-sensitivity detection for omics [23] | Liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometers (Orbitrap, Q-TOF) |

The core components of New Approach Methodologies—in vitro systems, in silico models, and omics technologies—individually provide valuable insights into chemical hazards and mechanisms of toxicity. However, their true transformative potential is realized when these approaches are strategically integrated, creating a synergistic framework that enhances the predictivity, human relevance, and efficiency of ecotoxicological assessment. As regulatory agencies worldwide increasingly accept and encourage these methodologies [3], the continued development and application of NAMs will play a crucial role in addressing the challenges of 21st-century toxicology, enabling more robust chemical safety assessment while reducing reliance on traditional animal testing.

The field of ecotoxicology is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by a global regulatory shift toward New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). These methodologies, which include in vitro assays, in silico models, and computational toxicology tools, are rapidly being integrated into the regulatory frameworks of major agencies worldwide including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This transition is motivated by the recognition that traditional animal testing approaches are insufficient to address the vast number of chemicals in commerce—estimated at over ten thousand substances, many lacking meaningful risk assessment data [24]. The 3Rs principle (reduce, replace, and refine animal use) provides the ethical foundation for this shift, while scientific advancements now enable more efficient, human-relevant toxicity assessment through integrated testing strategies [24].

Regulatory agencies are actively developing frameworks to implement NAMs for regulatory applications. The EPA has been establishing workflows that incorporate computational toxicology and high-throughput screening for chemical safety evaluation [24]. Similarly, the FDA participates in initiatives like the Eco-NAMS webinar series, which brings together international regulators to discuss the application of NAMs for ecotoxicity assessments [25]. The OECD has developed the Integrated Approaches for Testing and Assessment (IATA) framework, which combines multiple data sources—including from NAMs—to conclude on chemical toxicity, thereby supporting regulatory decision-making [24]. This collaborative, international effort represents a fundamental reimagining of chemical safety assessment that prioritizes mechanistic understanding, efficiency, and ethical considerations.

Global Regulatory Frameworks and Initiatives

Agency-Specific NAMs Adoption

Global regulatory agencies have established distinct but complementary initiatives to advance the adoption of NAMs in chemical risk assessment. The U.S. EPA has developed a robust computational toxicology program, evidenced by its suite of publicly available tools and databases. The CompTox Chemicals Dashboard serves as a centralized hub for chemical property, hazard, and exposure data, while tools like ToxCast/Tox21 provide high-throughput screening data from in vitro assays [14] [24]. The EPA's significant investment in NAMs training resources demonstrates its commitment to building scientific capacity, with recent virtual trainings covering toxicokinetic modeling using the httk R package, the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, and ecotoxicology tools like SeqAPASS and the ECOTOX Knowledgebase [14]. The agency is actively using these tools in regulatory contexts, such as prioritizing chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) and conducting risk evaluations for substances like phthalates and octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4) [26] [24].

The U.S. FDA has engaged with NAMs through specific qualification programs, particularly for targeted applications. The agency's biomarker qualification program provides a pathway for approving specific NAMs for regulatory use, as demonstrated by the qualification of Stemina's devTOX quickPredict assay, which uses human stem cells to predict developmental toxicity based on metabolic profiling [27]. The FDA also co-organizes the Eco-NAMS webinar series with international partners including the EPA, European Medicines Agency, and Health and Environmental Sciences Institute [25]. These collaborative efforts focus on building scientific consensus around NAMs applications for ecotoxicity assessments, with recent sessions addressing integrated weight-of-evidence approaches for bioaccumulation assessment [25].

The OECD plays a critical role in harmonizing international regulatory standards through its framework for IATA. The OECD IATA framework combines multiple sources of information—including in vitro and in silico data from NAMs—for hazard identification, characterization, and chemical safety assessment [24]. The organization has developed specific guidance for read-across and structurally similar compounds to support genotoxicity hazard assessment, facilitating the use of NAMs for filling data gaps [24]. The OECD OMICS reporting framework (OORF) represents another significant contribution, establishing standards to ensure the reproducibility and quality of OMICS data for regulatory application [24].

Table 1: Regulatory NAMs Tools and Their Applications in Chemical Risk Assessment

| Tool/Platform | Agency | Application in Risk Assessment | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | EPA | Chemical prioritization and data integration | Aggregates data for ~900,000 chemicals; links to ToxCast bioactivity data [14] |

| ToxCast/Tox21 | EPA/FDA | High-throughput screening | Provides bioactivity data from >1,000 assays for ~2,000 chemicals [24] |

| SeqAPASS | EPA | Species extrapolation | Predicts chemical susceptibility across species based on protein sequence similarity [14] |

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | EPA | Ecotoxicological effects data | Curated database of >1 million effect records for ~13,000 chemicals and ~13,000 species [14] |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | OECD | Read-across and grouping | Supports chemical category formation and read-across for data gap filling [24] |

| DeTox | Academic/FDA | Developmental toxicity prediction | QSAR model predicting developmental toxicity probability by trimester [27] |

Table 2: Recent Regulatory Activities Supporting NAMs Implementation (2024-2025)

| Agency | Activity/Initiative | Date | Regulatory Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA | TSCA Risk Evaluation Proposed Rule Amendments | Sep 2025 | Proposes changes to procedural framework for chemical risk evaluations under TSCA [26] |

| EPA/FDA | Eco-NAMS Webinar Series: Bioaccumulation | Sep 2025 | International collaboration on weight-of-evidence approaches for bioaccumulation assessment [25] |

| EPA | NAMs Training Workshops (httk, SeqAPASS, CompTox) | 2024-2025 | Builds scientific capacity for NAMs implementation among researchers and regulators [14] |

| OECD | IATA Framework Development | Ongoing | Provides structure for integrating multiple data sources in chemical assessment [24] |

| EPA | Phthalates Risk Evaluation (SACC peer review) | Aug 2025 | Incorporates NAMs data in risk evaluation for five phthalates [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol 1: High-Through Transcriptomics for Chemical Prioritization

This protocol describes a standardized approach for utilizing high-throughput transcriptomic data within a NAMs framework to prioritize chemicals for further regulatory assessment. The method enables rapid screening of chemical effects on biological pathways, providing mechanistic insight for hazard identification while reducing animal testing.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Culture: Appropriate cell lines (e.g., HepG2, MCF-7, or primary hepatocytes), culture media, fetal bovine serum, antibiotics

- Chemical Exposure: Test chemicals dissolved in DMSO or appropriate vehicle, concentration series, positive control compounds

- RNA Isolation: TRIzol reagent, RNA purification kit, DNase treatment reagents

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: mRNA enrichment kits, cDNA synthesis reagents, sequencing adapters, barcoded primers

- Bioinformatics: Access to RNA-seq analysis pipeline (e.g., FastQC, STAR, DESeq2), computational resources

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Exposure: Culture cells under standard conditions. At 70-80% confluence, expose to a concentration series of test chemicals for 24 hours. Include vehicle controls and positive controls. Use at least three biological replicates per condition.

- RNA Isolation and Quality Control: Harvest cells and isolate total RNA. Assess RNA quality using Bioanalyzer or similar system; ensure RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >8.0 for all samples.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare mRNA sequencing libraries using standardized kits. Perform quality control on libraries. Sequence on appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina) to a minimum depth of 20 million reads per sample.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process raw sequencing data through quality control, alignment to reference genome, and gene-level quantification. Perform differential expression analysis comparing treated to control samples.

- Benchmark Dose (BMD) Modeling: Conduct BMD modeling on significantly altered genes and pathways using software such as BMDExpress. Calculate point of departure (POD) values based on transcriptional pathway perturbations.

- Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Enrichment: Analyze differentially expressed genes for enrichment in established AOP networks using tools like AOP-Wiki to identify potential mechanistic links to adverse outcomes.

Data Interpretation: The BMD values derived from transcriptomic perturbations provide a quantitative basis for chemical prioritization. Chemicals demonstrating significant pathway alterations at low concentrations should be prioritized for further testing. The AOP enrichment analysis helps contextualize transcriptomic changes within existing toxicological knowledge, supporting weight-of-evidence determinations [24].

Protocol 2: IntegratedIn Vitro-In VivoExtrapolation (IVIVE) for Risk Assessment

This protocol outlines a standardized approach for translating in vitro bioactivity data to human exposure context using high-throughput toxicokinetic modeling and reverse dosimetry, enabling quantitative risk assessment without animal studies.

Materials and Reagents:

- In Vitro Bioactivity Data: Concentration-response data from ToxCast/Tox21 assays or other high-throughput screening platforms

- Toxicokinetic Modeling Tools: Access to R package 'httk' (high-throughput toxicokinetics) or comparable platforms (GastroPlus, PK-Sim)

- Chemical Property Data: Physicochemical parameters (log P, pKa, molecular weight), plasma protein binding data, metabolic clearance rates

- Computational Resources: R statistical programming environment, appropriate computing hardware

Procedure:

- Data Compilation: Compile in vitro bioactivity data for test chemical, including AC50 values (concentration causing 50% activity) and efficacy measures from relevant ToxCast/Tox21 assays.

- Toxicokinetic Parameterization: Input chemical-specific properties into the 'httk' package. For data-poor chemicals, use quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) predictions to estimate required parameters.

- IVIVE Modeling: Use the 'httk' package to perform reverse dosimetry calculations, converting in vitro bioactivity concentrations to equivalent human oral doses using the following approach:

- Calculate plasma Cmax (maximum concentration) for a series of hypothetical daily oral doses

- Determine the oral dose that would produce a plasma Cmax equal to the in vitro bioactivity concentration (AC50)

- Apply appropriate uncertainty factors based on toxicodynamic variability and experimental uncertainty

- Bioactivity:Exposure Ratio (BER) Calculation: Compare the oral equivalent dose derived from IVIVE to estimated human exposure levels from biomonitoring data or exposure models. Calculate BER as: BER = Oral Equivalent Dose (from IVIVE) / Human Exposure Estimate

- Risk Characterization: Interpret BER values according to established risk characterization frameworks. BER < 1 suggests potential concern, while BER > 100 suggests low concern, with intermediate values requiring additional assessment.

Data Interpretation: The IVIVE approach provides a quantitative bridge between in vitro bioactivity and human exposure context. This methodology has been demonstrated to produce predictions consistent with traditional risk assessment approaches while offering significant advantages in speed and cost [27]. The BER provides a conservative, protective screening tool for prioritizing chemicals requiring more comprehensive assessment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for NAMs Implementation

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

httk R Package |

Computational | High-throughput toxicokinetic modeling | IVIVE, in vitro to in vivo dose conversion [14] |

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | Database | Chemical property and bioactivity data aggregation | Chemical prioritization, data gap filling [14] |

| SeqAPASS | Computational | Cross-species extrapolation | Predicting chemical susceptibility for ecological risk assessment [14] |

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | Database | Curated ecotoxicology effects data | Deriving species sensitivity distributions [14] |

| ToxCast/Tox21 Data | Database | High-throughput screening bioactivity | Pathway-based hazard identification [24] |

| devTOX quickPredict | In vitro assay | Developmental toxicity prediction | Stem cell-based DART assessment [27] |

| DeTox Database | Computational | Developmental toxicity QSAR predictions | Chemical screening for developmental hazards [27] |

| Web-ICE | Computational | Interspecies correlation estimation | Acute toxicity prediction for data-poor species [14] |

Visualizing NAMs Workflows and Regulatory Integration

NAMs Implementation Workflow for Chemical Assessment

Regulatory Integration Pathway for NAMs

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress in regulatory adoption of NAMs, several challenges remain. Animal methods bias—the preference for animal experimentation among some researchers and regulators—continues to impact publishing and funding decisions. A recent survey of researchers in India found that approximately half had been asked by manuscript reviewers to add animal experiments to their otherwise non-animal studies, and over half felt that the lack of animal experiments in their grant proposals negatively influenced evaluation [28]. This bias represents a significant barrier to the broader implementation of more ethical and effective non-animal approaches.

Technical and validation challenges also persist, particularly for complex endpoints like developmental and reproductive toxicity (DART). While promising approaches are emerging—such as Stemina's devTOX quickPredict assay, zebrafish models for female reproductive toxicity, and tiered next generation risk assessment (NGRA) frameworks—consistent regulatory acceptance requires robust demonstration of predictivity [27]. The DeTox database, which uses QSAR modeling to predict developmental toxicity, faces challenges with "activity cliffs" where structurally similar chemicals demonstrate different toxicities, highlighting the need for mechanistic integration [27].

Future directions for NAMs in regulatory ecotoxicology will likely focus on several key areas. First, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning will enhance the predictive power of computational models, particularly for addressing activity cliffs and improving extrapolation accuracy. Second, the development of standardized reporting frameworks following FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles will promote data quality and regulatory acceptance [24]. Finally, international harmonization of validation criteria and regulatory frameworks will be essential for global implementation of NAMs, reducing redundant testing and accelerating chemical safety assessments worldwide. As regulatory agencies continue to build scientific capacity through training and collaborative initiatives, the vision of toxicity testing for the 21st century is progressively becoming a reality [14] [25] [24].

NAMs in Action: From Organ-on-a-Chip to Computational Dashboards

The field of ecotoxicology is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving away from heavy reliance on traditional animal models toward more human-relevant and mechanistic-based testing strategies. This evolution is driven by New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), which encompass innovative in vitro and in silico tools designed to provide more predictive data while adhering to the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement of animal testing) [29] [30]. Among the most promising NAMs are advanced in vitro systems, which have progressed from simple two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures to complex, physiologically relevant three-dimensional (3D) Microphysiological Systems (MPS) [31] [24]. These systems are increasingly critical for evaluating the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME-Tox) of chemicals and drugs, offering a more accurate foundation for environmental risk assessment and drug development [31] [32].

The core advantage of these advanced in vitro models lies in their ability to more closely mimic human physiology. This is particularly valuable for ecotoxicology research, where understanding the potential impact of environmental chemicals on human health is paramount. MPS, often referred to as organ-on-a-chip technology, incorporates microfluidic channels, living cells, and extracellular matrix components to recreate the dynamic microenvironment of human tissues and organs [31]. This capability allows for a deeper investigation of biological processes and improves predictions of how therapeutics and environmental toxins will behave in the human body [31].

The Evolution and Comparison of In Vitro Models

The journey of in vitro models began with conventional 2D cell cultures. While these systems have been invaluable for studying fundamental cell functions and performing high-throughput assays, they possess significant limitations. The primary issue is their inability to accurately replicate human physiology, which can lead to misleading, incomplete, or inaccurate data [31]. Cells cultured in 2D often lose their native morphology and functional characteristics due to a lack of proper cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, and they experience diffusion-limited access to nutrients and oxygen in a static environment [31].

The need for more physiologically relevant models spurred the development of 3D culture systems, such as spheroids. While an improvement, these still do not fully replicate the complex environmental factors necessary for optimal cellular growth [31]. MPS represents the current state-of-the-art, designed to resemble the 3D structure, various cell types, and extracellular matrix found in human organs [31]. A crucial differentiator for MPS is the incorporation of dynamic fluid flow, which facilitates the continuous delivery of nutrients and removal of cellular waste, more closely mimicking the in vivo environment [31]. This dynamic system helps maintain cell viability and the expression of key functional proteins, such as drug-metabolizing enzymes [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional and Advanced In Vitro Model Systems

| Feature | 2D Cell Culture | 3D Spheroids | Microphysiological Systems (MPS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Complexity | Monolayer; Low | Spherical aggregates; Medium | Tissue-specific 3D architecture; High |

| Microenvironment | Static, diffusion-limited | Static, but with gradients | Dynamic fluid flow; Physiologically relevant |

| Cell-Cell/Matrix Interactions | Limited | Moderate | High, including mechanical forces |

| Physiological Relevance | Low; Altered cell signaling | Medium; Better for some cancer studies | High; Recapitulates key organ functions |

| Expression of Drug Metabolizing Enzymes (e.g., CYPs) | Often rapidly lost | Improved over 2D | Enhanced and sustained under flow [31] |

| Utility for ADME-Tox | Limited translational accuracy | Useful for drug screening | High accuracy for evaluating drug ADME and toxicity [31] |

| Throughput & Cost | High throughput, Low cost | Medium throughput & cost | Lower throughput, Higher cost |

Key Application Areas and Experimental Data from MPS

ADME and Toxicity Evaluation

A significant application of MPS is in the evaluation of drug ADME and toxicity. One of the leading causes of candidate drug failure is an inadequate pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile [31]. MPS addresses this by integrating pharmacological processes into a single, closed in vitro system, providing higher accuracy in drug evaluation [31]. For instance, studies have shown that liver MPS models exhibit remarkably increased expression and activity of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, which are crucial for drug metabolism, compared to static culture systems [31]. This enhanced metabolic competence makes MPS superior for predicting drug safety and metabolism in humans.

Cardiac Toxicity Assessment

MPS are also proving invaluable for screening organ-specific toxicities, such as cardiotoxicity. The Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) has championed the use of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) and engineered heart tissues (EHTs) within a NAMs framework to predict specific "cardiac failure modes" like contractility dysfunction and rhythmicity (arrhythmias) [33]. Case studies have demonstrated that 3D EHTs can model complex conditions like tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, revealing insights into tissue recovery mechanisms that were not apparent from traditional models [33]. Furthermore, innovative platforms using graphene-mediated optical stimulation of cardiomyocytes offer a more precise method for screening drug effects on cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmias [33].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of CYP Enzyme Expression in In Vitro Models

| Study / System | Cell Type / Model | Key Finding on CYP Expression/Activity | Significance for Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kwon et al. [31] | Liver acinus dynamic (LADY) chip | Remarkably increased expression of CYP2E1 vs. static culture | Improves prediction of metabolism for drugs that are CYP2E1 substrates. |

| Cox et al. [31] | Liver-on-chip platform | CYP activity comparable to liver spheroids and notably higher than conventional plate cultures | Provides a more physiologically relevant model for hepatic metabolism studies. |

| General Finding [31] | Dynamic MPS vs. Static Culture | Dynamic systems generally promote higher expression of CYP enzymes | Enhances the accuracy of in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) for drug safety. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key MPS Assays

Protocol 1: Establishing a Liver MPS for Metabolic Stability Assessment

This protocol outlines the steps for using a liver MPS to measure the metabolic stability of a new chemical entity, a critical parameter in ADME evaluation.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Primary Human Hepatocytes or HepaRG Cells: Provide a metabolically competent liver model. HepaRG cells are a promising alternative due to their high metabolic enzyme activities [31].

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Hydrogel: (e.g., Collagen I, Matrigel) to provide a 3D scaffold that supports hepatocyte function and polarity.

- Hepatocyte Maintenance Medium: A specialized medium supplemented with growth factors, hormones, and antibiotics to maintain liver-specific functions.

- Test Compound Solution: The drug candidate dissolved in an appropriate vehicle (e.g., DMSO, concentration typically <0.1%).

- Substrate for CYP Enzymes: (e.g., Testosterone for CYP3A4) to probe specific metabolic activities.

- LC-MS/MS Solvents: Acetonitrile, methanol, and formic acid for sample preparation and analysis.

Procedure:

- MPS Priming: Load the microfluidic channels of the MPS device with ECM hydrogel and allow it to polymerize under controlled conditions (e.g., 37°C for 1 hour).

- Cell Seeding: Introduce a suspension of primary human hepatocytes or HepaRG cells (e.g., 5-10 x 10^6 cells/mL) into the device's culture chamber. Allow cells to attach for several hours.

- System Initiation: Connect the MPS device to the perfusion system and initiate flow of the maintenance medium at a physiologically relevant shear stress (e.g., 0.5 - 1.0 dyn/cm²). Culture the liver model for 3-7 days to allow for full functional maturation and formation of bile canaliculi.

- Dosing and Sampling: a. Introduce the test compound solution (at a predefined concentration, e.g., 1 µM) into the perfusion medium. b. Collect effluent (outflow) samples from the MPS at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes). c. Immediately quench the samples with an equal volume of ice-cold acetonitrile containing an internal standard to precipitate proteins and stop metabolic reactions.

- Sample Analysis: a. Centrifuge the quenched samples and analyze the supernatant using Liquid Chromatography with tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). b. Quantify the remaining concentration of the parent drug over time.

- Data Analysis: a. Plot the natural logarithm of the parent drug concentration versus time. b. Calculate the elimination rate constant (k) from the slope of the linear phase. c. Determine the in vitro half-life (tâ‚/â‚‚ = 0.693/k) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) using standard equations.

Diagram 1: Liver MPS Metabolic Assay Workflow.

Protocol 2: Assessing Vascular Toxicity Using a Microfluidic BioFlux Model

This protocol describes the use of a microfluidic system to predict drug-induced vascular injury, a key cardiac failure mode, by measuring monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells.