Modern Strategies for Chemical Mixture Risk Assessment: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of assessing health risks from chemical mixtures, moving beyond traditional single-chemical evaluation paradigms.

Modern Strategies for Chemical Mixture Risk Assessment: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

Abstract

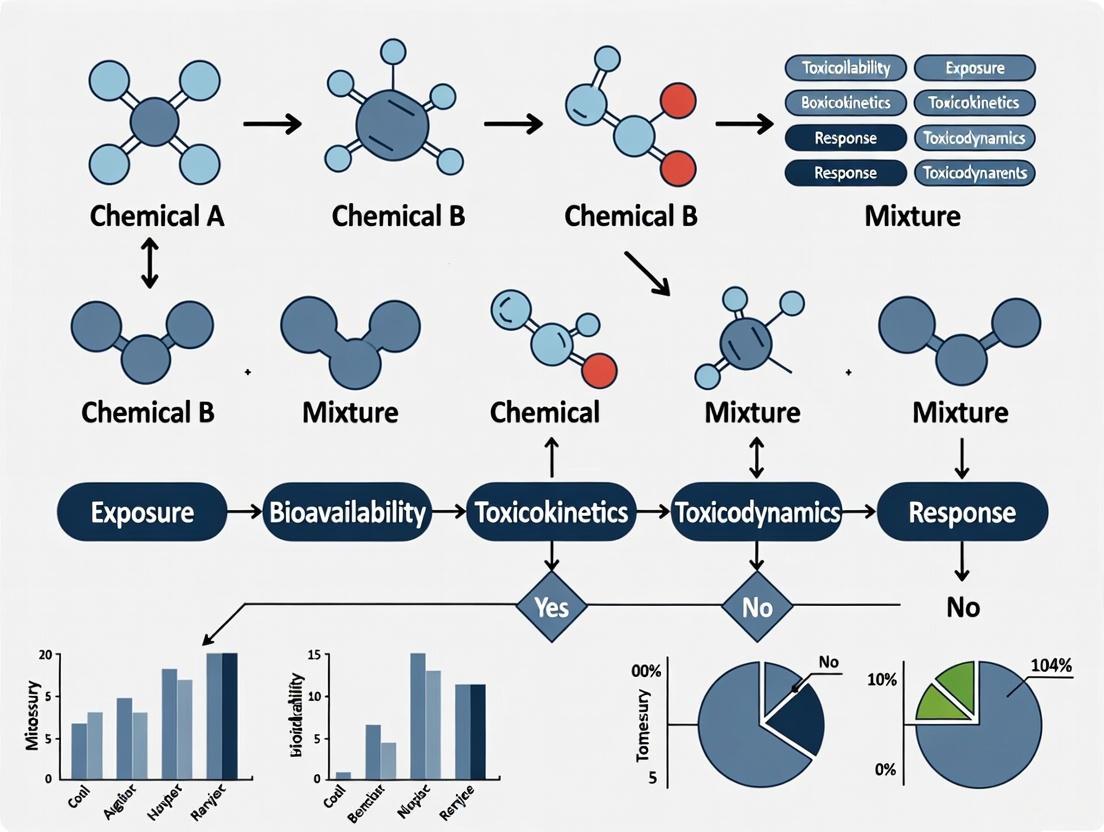

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of assessing health risks from chemical mixtures, moving beyond traditional single-chemical evaluation paradigms. We explore foundational toxicological concepts, advanced methodological frameworks including computational tools like the MRA Toolbox, and current regulatory guidelines. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article synthesizes evidence on mixture toxicity mechanisms, assessment methodologies, and emerging solutions for complex risk scenarios. Special emphasis is placed on troubleshooting common assessment challenges and validating approaches through comparative analysis of whole-mixture versus component-based strategies.

Understanding Chemical Mixture Toxicology: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Analytical Challenges

Q1: Our mixture experiment yielded unexpected synergistic toxicity. How should we adjust our risk assessment approach?

Unexpected synergism, where the combined effect is greater than the sum of individual effects, requires moving beyond simple additive models.

- Confirm the Interaction: First, verify the synergistic effect is reproducible. Rule out experimental artifacts or issues with chemical stability in your mixture.

- Refine the Hazard Assessment: Abandon the default assumption of dose addition for these components [1]. Investigate the Toxicokinetic (TK) and Toxicodynamic (TD) interactions. The Aggregate Exposure Pathway (AEP) – Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework can help map where interactions occur (e.g., competition for metabolism, or shared target receptors) [1].

- Adjust Risk Characterisation: A simple component-based approach using dose addition may no longer be sufficient. You may need to apply response-surface modeling (e.g., Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression - BKMR) to characterize the interaction, or treat the specific synergistic combination as a distinct "whole mixture" for risk assessment purposes [1] [2].

Q2: We are studying a complex, poorly-defined environmental mixture. How can we prioritize components for analysis?

Prioritizing components for a poorly defined mixture is a common challenge in moving towards exposome-level research.

- Apply a Tiered Approach: Start with a low-tier, conservative screening. Use exposure-driven prioritization (prioritize chemicals with highest exposure levels) or a risk-based approach (consider both exposure and inherent toxicity) [1].

- Leverage Hazard-Driven Grouping: Group chemicals into "Assessment Groups" based on common mechanisms of toxicity, such as shared Mode of Action (MoA) or Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP), even if their chemical structures differ [1] [3].

- Use Advanced Analytics: For data-rich scenarios, employ statistical methods like Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) regression to identify chemicals that contribute most significantly to the observed mixture effect [2].

Q3: Our statistical models for mixture effects suffer from high multicollinearity among components. What are our options?

High correlation between exposure variables is a central challenge in mixture epidemiology.

- Choose Robust Mixture Methods: Several methods are designed to handle correlated components.

- Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR): Excellently handles multicollinearity and can model complex non-linear and interaction effects [2].

- Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) Regression: Creates a single index from the weighted sum of correlated components, reducing dimensionality [2].

- Quantile g-computation: An extension that allows both positive and negative weights, relaxing some WQS assumptions [2].

- Method Triangulation: Do not rely on a single method. Apply multiple complementary statistical approaches (e.g., BKMR, WQS, and main-effects regression) and look for consistent signals across models to strengthen causal inference [2].

Q4: How can we determine if two different samples of a complex botanical mixture are "sufficiently similar" for our research?

The "sufficient similarity" assessment ensures findings from one mixture variant can be extrapolated to others.

- Develop a Multi-Pronged Strategy: Relying on a single method is insufficient. A robust assessment combines:

- Non-Targeted Chemical Analysis: Use techniques like LC-HRMS to obtain comprehensive chemical profiles and compare the presence and abundance of constituents across samples [3].

- Targeted Analysis: Quantify key marker compounds known or suspected to be toxicologically relevant.

- In Vitro Bioassays: Test the mixtures in a battery of mechanistic cell-based assays (e.g., for receptor activation, cytotoxicity). Similar biological activity is a strong indicator of functional similarity, even with some chemical variability [3].

- Apply Statistical Comparison: Use multivariate statistics to quantitatively compare the chemical and bioassay profiles from different mixture samples and assess the degree of similarity [3].

Experimental Protocols for Mixture Risk Assessment

Protocol: Component-Based Risk Assessment (CBRA) for a Defined Mixture

This protocol outlines a tiered approach for assessing the risk of a chemically defined mixture, as recommended by EFSA [1].

1. Problem Formulation

- Define the Scope: Identify all chemicals in the mixture and the human population or ecological receptor of concern.

- Form Assessment Groups: Group chemicals based on shared toxicological properties, typically a common Mode of Action (MoA) [1].

2. Exposure Assessment

- Tier 0 (Screening): Use conservative point estimates (e.g., maximum exposure levels) from available data or models.

- Tier 1 (Deterministic): Refine estimates using more realistic average concentrations and exposure factors.

- Tier 2 (Probabilistic): Model the full distribution of exposure across the population using tools like SHEDS or APEX, accounting for variability in intake and exposure duration [1] [4].

3. Hazard Assessment

- Tier 0 (Default): Assume dose additivity for chemicals within an Assessment Group. Use Reference Doses (RfDs) or similar points of departure (PODs) from single-chemical studies.

- Tier 1 (Refined Additivity): Incorporate potency differences between components using the Relative Potency Factor (RPF) approach, designating one chemical as an index compound.

- Tier 2 (Interaction Testing): If data suggest interactions, conduct targeted mixture toxicity studies to derive chemical-specific interaction factors [1].

4. Risk Characterisation

- Calculate the Hazard Index (HI): For each Assessment Group, sum the Hazard Quotients (HQ = Exposure / POD) of all components.

HI = Σ HQi. An HI > 1 indicates potential risk requiring refinement or management [1] [4]. - Probabilistic Risk: In higher tiers, characterize the probability of exceeding a risk threshold across the exposed population.

Component-Based Risk Assessment Workflow

Protocol: Statistical Analysis of Mixture Health Effects in Epidemiological Studies

This protocol is based on prevalent methods identified in the scoping review of Persistent Organic Pollutant (POP) mixtures [2].

1. Data Preparation

- Handle Censored Data: For biomonitoring data with values below the limit of detection (LOD), use robust imputation methods (e.g., multiple imputation, maximum likelihood).

- Transform and Standardize: Log-transform exposure concentrations to reduce skewness. Standardize exposures (e.g., to z-scores) for comparability in some models.

2. Method Selection based on Research Question

- For Overall Mixture Effect:

- Primary: Use Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR) for its flexibility in handling correlations, non-linearity, and interactions [2].

- Secondary/Complementary: Apply Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) regression or Quantile g-computation to estimate a joint effect and identify key contributors.

- For Interaction Effects: BKMR is the preferred method as it can model component-wise exposure-response functions and pairwise interactions.

- For Exposure Pattern Identification: Use Latent Class Analysis or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify subpopulations with distinct exposure profiles.

3. Model Implementation & Validation

- Follow Published Code: For methods like BKMR and WQS, use well-documented R packages (e.g.,

bkmr,gWQS). - Incorporate Covariates: Adjust for key confounders (e.g., age, sex, socioeconomic status) as defined in your causal diagram.

- Conduct Sensitivity Analyses: Assess the robustness of results by varying the number of iterations, prior distributions (in Bayesian methods), and the set of adjusted covariates.

4. Interpretation and Reporting

- Visualize Results: Use BKMR plots to display the overall exposure-response relationship and component-wise plots.

- Report Key Estimates: For WQS/Quantile g-computation, report the overall mixture index and the weights of top contributors.

- Acknowledge Limitations: Clearly state the assumptions of your chosen method and the potential for residual confounding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Models

Table 1: Key Reagents and Models for Combined Exposure Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BKMR [2] | Statistical Model | Estimates overall mixture effect and interactions in correlated exposures. | Human epidemiology; hazard identification. |

| WQS Regression [2] | Statistical Model | Creates a weighted index to estimate overall effect and identify important mixture components. | Prioritizing chemicals in complex exposure studies. |

| SHEDS [5] [4] | Exposure Model | Probabilistic model for estimating aggregate (single chemical) exposure via multiple routes. | Modeling exposure to a pesticide in food, water, and residential settings. |

| APEX [4] | Exposure Model | Models cumulative (multiple chemicals) exposure for populations via multiple pathways. | Community-based risk assessment of air pollutants. |

| AEP-AOP Framework [1] | Conceptual Model | Integrates exposure, toxicokinetics, and toxicodynamics to map chemical fate and effects. | Mechanistic understanding of mixture component interactions. |

| Read-Across [3] | Analytical Approach | Determines if a new or variable mixture is "sufficiently similar" to a well-studied one. | Safety assessment of botanical extracts or complex reaction products. |

| Pyrronamycin A | Pyrronamycin A, MF:C23H29N11O5, MW:539.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Elloramycin | Elloramycin|C32H36O15|For Research Use | Elloramycin is an anthracycline-like antitumor agent and antibiotic for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Common Statistical Methods for Mixture Analysis (as of 2023 Review) [2]

| Method Category | Example Methods | Key Strengths | Primary Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response-Surface Modeling | Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR) | Handles correlation, non-linearity, interactions. | Overall effect & interactions. |

| Index Modeling | Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS), Quantile g-computation | Provides an overall effect estimate and component weights. | Overall effect & variable importance. |

| Dimension Reduction | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Factor Analysis | Reduces many exposure variables to fewer factors. | Exposure pattern identification. |

| Latent Variable Models | Latent Class Analysis | Identifies subpopulations with similar exposure profiles. | Exposure pattern identification. |

Mixture Analysis Research Questions

FAQs on Core Concepts

What is the key difference between synergism and potentiation?

Synergism occurs when two or more chemicals, each of which produces a toxic effect on their own, are combined and result in a health effect that is greater than the sum of their individual effects [6]. In contrast, potentiation occurs when a substance that does not normally have a toxic effect is added to another chemical, making the second chemical much more toxic [6]. For example, in synergism, 2 + 2 > 4, while in potentiation, 0 + 2 > 2 [6].

How do additive effects differ from synergistic ones?

Additive effects describe a combined effect that is equal to the sum of the effect of each agent given alone (e.g., 2 + 2 = 4) [6]. This is the most common type of interaction when two chemicals are given together and represents "no interaction" between the compounds [6] [7]. Synergistic effects are substantially greater than this sum (e.g., 2 + 2 >> 4) [6].

Why is antagonism important in toxicology?

Antagonism describes the situation where the combined effect of two or more compounds is less toxic than the individual effects (e.g., 4 + 6 < 10) [6]. This concept is crucial because antagonistic effects form the basis of many antidotes for poisonings and medical treatments [6]. For instance, ethyl alcohol can antagonize the toxic effects of methyl alcohol by displacing it from metabolic enzymes [6].

What are the real-world implications of these interactions in risk assessment?

Chemical risk assessment has traditionally evaluated substances individually, but real-world exposure involves mixtures [8]. Even when individual chemicals are present at concentrations below safety thresholds, their combined effects can pose significant health risks [8]. This has led scientific communities to advocate for regulatory changes, such as including a Mixture Assessment Factor in the revised EU REACH framework to account for cumulative impacts [8].

Troubleshooting Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Synergy Results Across Studies

Issue: Different reference models for defining additive interactions yield conflicting conclusions about whether combinations are synergistic.

Solution:

- Predefine your reference model before experimentation and maintain consistency in analysis [7].

- Understand model assumptions: Loewe Additivity assumes similar mechanisms, while Bliss Independence assumes independent mechanisms [7].

- Select the model that best aligns with the pharmacological mechanisms of your compounds.

Problem: Non-Traditional Dose-Response Curves

Issue: Compounds with hormetic (biphasic) or other non-traditional dose-response curves cannot be accurately assessed with standard synergy models [9].

Solution:

- Consider the Dose-Equivalence/Zero Interaction (DE/ZI) method, which can assess interactions for compounds with non-traditional curves using a nearest-neighbor approach [9].

- This method eliminates the need to determine the best-fit equation for a given data set and values experimentally-derived results over formulated fits [9].

Problem: Determining Optimal Dose Ratios

Issue: Identifying the specific dose combinations that produce synergistic effects while minimizing toxicity.

Solution:

- Implement isobolographic analysis to systematically map combination effects across different dose ratios [10].

- This graphical approach identifies dose pairs that produce a specified effect level (often EDâ‚…â‚€) and determines whether they plot below (synergism), on (additive), or above (antagonism) the predicted additive line [10].

Quantitative Assessment Methods

Table 1: Reference Models for Assessing Chemical Interactions

| Model Name | Definition | Key Assumptions | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loewe Additivity | Dose-based approach where drugs behave as dilutions of each other [7] | Similar mechanism of action; constant potency ratio [10] | Compounds with similar pharmacological targets |

| Bliss Independence | Effect-based probabilistic model where drugs act independently [7] | Independent mechanisms of action; effects expressed as probabilities [9] | Compounds with distinct molecular targets |

| Highest Single Agent | Combined effect exceeds the maximal effect of either drug alone [9] | None | Preliminary screening of combinations |

Table 2: Experimental Design Considerations for Combination Studies

| Parameter | Additivity Testing | Synergy Screening | Mechanistic Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose Range | 3-5 concentrations of each compound near EC₅₀ | Broad concentration matrix (e.g., 8×8) | Targeted around synergistic ratios |

| Replicates | Minimum n=3 | Minimum n=3 | Minimum n=5 for statistical power |

| Controls | Single agents, vehicle, positive control | Single agents, vehicle | Pathway-specific inhibitors |

| Analysis Method | Isobolographic analysis | Combination Index | DE/ZI for non-traditional curves |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isobolographic Analysis for Additivity Testing

Purpose: To determine whether a two-drug combination interacts synergistically, additively, or antagonistically at a specified effect level.

Materials:

- Test compounds in pure form

- Vehicle solution appropriate for compounds

- Cell culture or experimental model system

- Equipment for effect measurement (plate reader, etc.)

Procedure:

- Generate individual dose-response curves for each compound to determine ECâ‚…â‚€ values.

- Select a fixed ratio combination based on the ECâ‚…â‚€ values (e.g., 1:1, 1:2 ratios).

- Treat experimental system with combination doses maintaining the fixed ratio.

- Measure effects and calculate the total dose required to achieve the specified effect level (typically ECâ‚…â‚€).

- Plot the isobologram with Drug A dose on x-axis and Drug B dose on y-axis.

- Draw the line of additivity connecting the individual ECâ‚…â‚€ values.

- Statistically compare observed combination doses to expected additive doses.

Interpretation: Data points significantly below the additivity line indicate synergism; points above indicate antagonism [10].

Protocol 2: Bliss Independence Assessment

Purpose: To evaluate drug interactions under the assumption of independent mechanisms of action.

Procedure:

- Determine dose-response relationships for each drug alone.

- Express effects as fractional responses between 0 and 1.

- Apply Bliss Independence formula: EAB = EA + EB - (EA × EB), where EAB is the expected additive effect, and EA and EB are the effects of drugs A and B alone.

- Measure the actual combination effect experimentally.

- Calculate Bliss Excess = Eobserved - Eexpected.

Interpretation: Positive Bliss Excess values indicate synergy; negative values indicate antagonism [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| NTP CEBS Database [11] | Comprehensive toxicology database with curated chemical effects data | Accessing standardized toxicity data for mixture risk assessment |

| Integrated Chemical Environment (ICE) [11] | Data and tools for predicting chemical exposure effects | Screening potential mixture interactions before experimental work |

| Zebrafish Toxicology Models [11] | Alternative toxicological screening model | Higher-throughput assessment of mixture toxicity in whole organisms |

| High-Throughput Screening Robotics [11] | Automated systems for rapid toxicity testing | Efficiently testing multiple concentration combinations in chemical mixtures |

| Chlorogentisylquinone | Chlorogentisylquinone|High-Purity Reference Standard | Chlorogentisylquinone, a high-purity natural product reference standard for laboratory research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Vernakalant | Vernakalant|Atrial Fibrillation Research Compound | Vernakalant is an atrial-selective, mixed ion channel blocker for cardiovascular research. This product is for Research Use Only and not for human consumption. |

Diagnostic Workflows

Diagram 1: Chemical Interaction Assessment Workflow

Diagram 2: Synergism Mechanisms and Research Implications

Frameworks at a Glance

The "Multi-Headed Dragon" and "Synergy of Evil" are conceptual models that describe how different chemicals in a mixture can interact to cause adverse effects. Understanding these frameworks is crucial for accurate chemical risk assessment.

| Feature | 'Multi-Headed Dragon' Concept | 'Synergy of Evil' Concept |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Additive effects from substances sharing a common molecular mechanism or target [12] [13] | One substance ("enhancer") amplifies the toxicity of another ("driver") [12] |

| Primary Interaction | Similar mechanism of action or converging key events [12] | Toxicokinetic or toxicodynamic enhancement [12] |

| Nature of Effect | Primarily additive [13] | More than additive (synergistic) [13] |

| Risk Management Implication | Adequate management of individual substances can prevent effects [12] | Adequate management of individual substances can prevent effects [12] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

FAQ: How do I test for the "Multi-Headed Dragon" effect?

To test for this additive effect, you must determine if combined substances act on the same molecular target or pathway. The following workflow outlines the key experimental steps, which rely on the Loewe Additivity model and Isobologram Analysis [13].

Detailed Procedure:

- Individual Substance Characterization: For each substance, measure the concentration-response relationship using 6-10 concentrations. Perform at least three independent experiments to fit a log-logistic curve and determine a robust toxicity indicator, such as the EC20 (the concentration that produces 80% viability) [13].

- Fixed-Proportion Mixture Preparation: Create the test mixture by combining each substance at a concentration proportional to its individual EC20. For example, a mixture might contain each substance at 0.1 x its EC20, 0.5 x its EC20, etc. [13].

- Mixture Effect Measurement: In a new, independent experiment, measure the viability (or other relevant endpoint) of cells exposed to the prepared mixture proportions.

- Data Analysis with Loewe Additivity:

- Use the Budget Approach, an extension of the Loewe additivity model for multiple substances, as your reference model for additivity [13].

- Calculate the Interaction Index.

- Compare the observed mixture effect to the predicted additive effect. An observed effect greater than predicted indicates synergism, while a lesser effect indicates antagonism [13].

FAQ: How do I test for the "Synergy of Evil" effect?

This tests for synergistic interactions where one chemical enhances the effect of another. The protocol focuses on identifying and characterizing the "enhancer" and "driver" relationship.

Detailed Procedure:

- Hypothesis and Compound Selection: Based on known metabolism or mode of action, identify a potential "driver" chemical (primary toxicant) and an "enhancer" (e.g., a compound that may inhibit the driver's detoxification enzymes).

- Toxicokinetic Investigation:

- Use Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to predict how the enhancer alters the target tissue dose of the driver [14].

- Experimentally, in vitro systems with human hepatocytes or relevant cell lines can be used to measure the inhibition of key cytochrome P450 enzymes by the enhancer, which would lead to increased bioavailability of the driver.

- Toxicodynamic Investigation:

- Test the driver substance alone across a range of doses to establish its baseline dose-response curve.

- Test the enhancer substance alone at a low, presumably non-toxic dose to confirm it has no significant effect.

- Co-expose the biological system to the non-toxic dose of the enhancer and various doses of the driver. A significant leftward shift in the driver's dose-response curve indicates a toxicodynamic synergistic interaction.

- Data Analysis: The Bliss Independence model is often suitable for analyzing this type of interaction, where substances are assumed to act independently. A combined effect greater than that predicted by the multiplicative product of their individual effects confirms synergism [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Mixture Toxicity Studies |

|---|---|

| In Vitro Toxicity Assays | Measures cell viability (e.g., ATP levels, membrane integrity) as a response to individual substances and mixtures. The foundation for determining EC values [13]. |

| Fixed-Proportion Mixtures | Test mixtures created by combining individual substances at fractions of their pre-determined EC20 values. This design is central to the Budget Approach and Loewe additivity testing [13]. |

| Log-Logistic Model | A parametric sigmoidal model class used to fit concentration-response data from individual substances, allowing for the robust calculation of EC20 and other alerts [13]. |

| Loewe Additivity Model | A reference model for additivity. It calculates an "Interaction Index" to determine if a mixture's effect is additive, synergistic, or antagonistic [13]. |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Models | Computational tools that predict how chemicals are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted. Crucial for predicting target tissue doses and identifying toxicokinetic interactions in "Synergy of Evil" [14]. |

| Benchmark Dose (BMD) Modeling | A more robust statistical method than NOAEL for determining a Point of Departure (PoD) for risk assessment, using the entire dose-response curve [12]. |

| Promothiocin B | Promothiocin B, CAS:156737-06-3, MF:C42H43N13O10S2, MW:954.0 g/mol |

| Kigamicin D | Kigamicin D, MF:C48H59NO19, MW:954.0 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: How can I account for high day-to-day variability in my mixture experiments?

Day-to-day variability is a major challenge when mixture experiments (step 2) are conducted separately from individual substance characterization (step 1) [13].

- Problem: Cytotoxicity measurements for the same reference substance can vary between experiments conducted on different days, leading to inaccurate assessment of mixture interactions [13].

- Solution: Incorporate a single concentration of each reference substance in the same experimental batch as the mixture tests. This provides an internal control that allows for statistical adjustment of the day-to-day variability, aligning the results from the mixture experiment with the historical dose-response curves [13].

FAQ: My data is inconclusive. Which additivity model should I use?

Choosing the right model is critical for correct interpretation.

- For "Multi-Headed Dragon" (Similar Mode of Action): The Loewe Additivity model is typically the most appropriate. It is the foundation for the "Budget Approach" used for multi-substance mixtures and is based on the idea of dose addition [13].

- For "Synergy of Evil" (Potential Independent Action): The Bliss Independence model can be a good starting point, as it assumes the substances act via different mechanisms [13].

- General Guidance: A review by Cedergreen (2014) notes that synergistic interactions are rare, and additive models most often explain mixture effects. If you are observing significant synergism, ensure your experimental design and model assumptions are correct [13].

FAQ: What is the "Revolting Dwarfs" hypothesis?

This is a third, more hypothetical concept. It proposes that a large number of substances, each at a very low dose below its individual safety threshold, could somehow combine to cause significant adverse effects [12] [13].

- Current Scientific Consensus: The article by Bloch et al. (2023) concludes that there is currently no experimental evidence or plausible mechanism supporting this hypothesis [12].

- Implication for Your Research: While it is important to be aware of this debate, current risk assessment practices and your experimental frameworks should focus on the well-established "Multi-Headed Dragon" and "Synergy of Evil" concepts.

Dose-Response Relationships and Threshold Considerations in Mixture Toxicology

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: My dose-response curve for a chemical mixture does not show a clear sigmoidal shape. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Dose Spacing

- Diagnosis: If the doses tested are too close together, you may not capture the full range of the response, from the threshold to the maximum effect plateau [15].

- Solution: Redesign the experiment to include a wider range of doses, ensuring you cover suspected threshold levels and the upper response plateau. A pilot study can help determine an appropriate dosing range.

- Potential Cause 2: Interactions Between Mixture Components

- Diagnosis: The mixture may contain compounds that interact, leading to additive, synergistic (more-than-additive), or antagonistic (less-than-additive) effects that distort the expected curve shape [12].

- Solution: Conduct dose-response testing on individual components to establish their baseline activity. This allows you to compare the observed mixture effect with the effect predicted by models like concentration addition (for similarly acting chemicals) [12].

- Potential Cause 3: The Mixture Contains Compounds with Differing Mechanisms of Action

- Diagnosis: The "revolting dwarfs" hypothesis suggests that chemicals acting via disparate mechanisms at low doses might not produce a classic sigmoidal curve, though evidence for this is currently limited [12].

- Solution: Investigate the molecular mechanisms of key components. Group chemicals based on their mode of action (e.g., all compounds activating a specific receptor) and analyze those subgroups separately [12].

- Potential Cause 1: Insensitive or Poorly Chosen Endpoint

- Diagnosis: The biological endpoint you are measuring (e.g., a general health observation) may not be the most sensitive effect caused by the mixture [16].

- Solution: Incorporate more sensitive, mechanistic endpoints. For instance, instead of just observing liver weight changes, measure specific serum biomarkers like ALT or AST, or conduct histological examinations to detect more subtle damage [17] [16].

- Potential Cause 2: High Variability in Response Data

- Diagnosis: Significant scatter in the data at low doses can make it statistically difficult to distinguish a true effect from background noise [15].

- Solution: Increase your sample size to improve statistical power. Consider using the Benchmark Dose (BMD) approach, which uses all the dose-response data to model a point of departure (the BMDL), which is often more robust and reliable than NOAEL/LOAEL [17] [15] [12].

- Potential Cause 3: The Mixture Contains a Carcinogen

- Diagnosis: For carcinogens with a genotoxic mode of action, it is traditionally assumed that there is no threshold, meaning any dose carries some theoretical risk [17] [16].

- Solution: Identify if your mixture contains known genotoxic carcinogens. The dose-response assessment will then focus on determining the potency (cancer slope factor) rather than a threshold, often resulting in a linear low-dose extrapolation [16].

Issue 3: My in vitro mixture toxicity data does not align with in vivo observations.

- Potential Cause: Differences in Toxicokinetics

- Diagnosis: In vitro systems often lack the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) processes of a whole organism. A substance that is metabolically activated in the liver (a toxicokinetic "synergy of evil") will not show this effect in a simple cell culture [12].

- Solution: Use more advanced in vitro models that incorporate metabolic competence, such as systems with S9 liver fractions or co-cultures with hepatocytes. Follow up with toxicokinetic (PBPK) modeling to simulate in vivo conditions [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the fundamental difference between dose-response assessment for carcinogens and non-carcinogens?

A: The key difference lies in the assumption of a threshold. For most non-carcinogenic effects, a dose (the No Observed Adverse Effect Level, or NOAEL) below which no adverse effect occurs is assumed [17] [16]. For genotoxic carcinogens, it is often assumed that there is no safe threshold and even very low doses pose some level of risk, leading to a linear dose-response model at low doses [17] [16]. The assessment for non-carcinogens focuses on finding a safe dose (e.g., Reference Dose), while for carcinogens, it focuses on estimating the probability of cancer risk (potency) [16].

Q: What are NOAEL, LOAEL, and BMD, and how do they relate?

A:

- NOAEL (No Observed Adverse Effect Level): The highest tested dose where no statistically or biologically significant adverse effects are observed [17] [15] [16].

- LOAEL (Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level): The lowest tested dose where a statistically or biologically significant adverse effect is observed [17] [15] [16].

- BMD (Benchmark Dose): A model-derived dose that produces a predetermined change in response rate (e.g., a 10% increase in effect). The lower confidence limit (BMDL) is often used as the Point of Departure [17] [15] [12].

The BMD approach is generally preferred over NOAEL/LOAEL because it is less dependent on dose spacing, uses all experimental data, and accounts for statistical variability [15] [12].

Q: How do I account for species differences when extrapolating animal dose-response data to humans?

A: This is typically done by applying Uncertainty Factors (UFs) or Assessment Factors to the Point of Departure (e.g., NOAEL or BMDL) [17] [16]. A common default is to use a 10-fold factor for interspecies differences and another 10-fold factor for intraspecies (human) variability, resulting in a total UF of 100 [16]. These factors can be adjusted with substance-specific data. More sophisticated methods, like Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, provide a more scientific basis for this extrapolation by simulating the chemical's behavior in different species [15].

Q: What are the main concepts for how chemicals in a mixture interact?

A: Two primary established concepts are [12]:

- The "Multi-Headed Dragon" (Additivity): Several chemicals in the mixture act by the same molecular mechanism, targeting the same biological site. Their effects add up, even if each individual chemical is present at a low, seemingly harmless dose [12].

- The "Synergy of Evil" (Interaction): One chemical ("enhancer") increases the toxicity of another ("driver"). This can happen by the enhancer inhibiting the driver's detoxification enzymes (toxicokinetic synergy) or by amplifying its toxic effect at the target site (toxicodynamic synergy) [12].

Q: Why is risk assessment for chemical mixtures so challenging, and what new approaches are being discussed?

A: Risk assessment has traditionally been performed for single chemicals, but humans and ecosystems are exposed to complex mixtures [8]. The main challenge is that even when individual chemicals are below their safe thresholds, their combined effect can be significant [8] [12]. To address this, regulatory scientists are debating the introduction of a Mixture Assessment Factor (MAF). A MAF is a generic factor that would lower the acceptable exposure limit for all substances to account for potential mixture effects, though this approach is subject to ongoing scientific debate [8] [12].

The table below summarizes critical parameters derived from dose-response assessments [17] [15] [16].

| Parameter | Acronym | Definition | Application in Risk Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Observed Adverse Effect Level | NOAEL | Highest dose where no adverse effects are observed. | Used to derive safe exposure levels (e.g., RfD) by applying Uncertainty Factors. |

| Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level | LOAEL | Lowest dose where an adverse effect is observed. | Used when a NOAEL cannot be determined; requires an additional UF. |

| Benchmark Dose | BMD | A model-derived dose for a predetermined benchmark response (BMR). | A more robust Point of Departure than NOAEL/LOAEL; uses the entire dose-response curve. |

| Reference Dose | RfD | An estimate of a daily oral exposure safe for a human population. | Calculated as RfD = NOAEL or BMDL / (Uncertainty Factors). Used for non-cancer risk. |

| Cancer Slope Factor | CSF | An upper-bound estimate of risk per unit intake of a carcinogen over a lifetime. | Used to estimate cancer probability at different exposure levels for carcinogens. |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Dose-Response Curve for a Chemical Mixture

Objective: To determine the dose-response relationship and identify key toxicological parameters (NOAEL, LOAEL, EDâ‚…â‚€) for a defined chemical mixture in an in vivo model.

Materials:

- Test Substances: Purified compounds constituting the mixture.

- Vehicle: A suitable solvent (e.g., corn oil, saline, dimethyl sulfoxide diluted appropriately).

- Animals: Laboratory rodents (e.g., rats), with group size determined by power analysis (typically n=10-12 per group) to ensure statistical significance [15].

- Equipment: Dosing apparatus (gavage needles, inhalation chambers, etc.), clinical pathology analyzers, tissue processing equipment for histopathology.

Procedure:

- Mixture Formulation: Prepare the chemical mixture at a fixed ratio based on anticipated human exposure or environmental relevance. Maintain this ratio across all dose groups.

- Dose Selection: Based on pilot studies or literature, select at least five dose levels plus a vehicle control group. The doses should span from a level expected to produce no effect to one that produces a clear adverse effect [15].

- Animal Dosing: Randomly assign animals to each dose group and the control. Administer the mixture daily via the relevant route (e.g., oral gavage) for a defined period (e.g., 28 days for a subacute study).

- In-life Observations: Record daily clinical observations (mortality, morbidity, signs of toxicity) and weekly body weights and food consumption.

- Terminal Procedures: At study termination, collect blood for clinical chemistry (e.g., liver enzymes, kidney biomarkers) and perform a gross necropsy. Weigh key organs (liver, kidneys, brain, etc.) and preserve tissues in formalin for histopathological examination [16].

- Data Analysis:

- Quantal Data: For "all-or-none" effects (e.g., presence of a tumor), use probit or logit analysis to calculate effective doses (EDâ‚…â‚€).

- Graded Data: For continuous data (e.g., enzyme activity, organ weight), use regression analysis to model the dose-response curve. Statistically compare each dosed group to the control group (e.g., using ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test) to identify the NOAEL and LOAEL [15] [16].

- BMD Modeling: Input the continuous or quantal data into BMD software (e.g., US EPA's BMDS) to derive a BMDL for a predefined BMR (e.g., 10% extra risk) [12].

Conceptual Workflow for Mixture Risk Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for assessing the risk of chemical mixtures, integrating dose-response and threshold considerations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Mixture Toxicology |

|---|---|

| Defined Chemical Mixtures | Custom-blended solutions of contaminants (e.g., PFAS, pesticides) used as the test agent to simulate real-world exposure in experimental models [8]. |

| Metabolic Activation Systems (e.g., S9 Fraction) | Liver subcellular fractions used in in vitro assays to provide metabolic competence, crucial for detecting toxins that require metabolic activation (pro-toxins) [12]. |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Commercial kits for measuring specific biomarkers of effect (e.g., oxidative stress, inflammation) or exposure (e.g., chemical adducts) in biological samples [16]. |

| Benchmark Dose (BMD) Software | Statistical software (e.g., US EPA's BMDS) used to model dose-response data and derive a more robust Point of Departure (BMDL) than NOAEL/LOAEL [15] [18]. |

| Positive Control Substances | Known toxicants (e.g., carbon tetrachloride for hepatotoxicity) used to validate the sensitivity and responsiveness of the experimental system [16]. |

| Dehydrocurdione | Dehydrocurdione|For Research |

| Griseoviridin | Griseoviridin, CAS:53216-90-3, MF:C22H27N3O7S, MW:477.5 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are critical windows of exposure in developmental toxicity, and why are they important for risk assessment? Critical windows of exposure are specific developmental stages during which an organism is particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of environmental insults. These windows correspond to key developmental processes, such as organ formation or functional maturation. Identifying these periods is crucial for risk assessment because exposure to the same agent at different developmental stages can produce dramatically different outcomes. For example, research shows that broad windows of sensitivity can be identified for many biological systems, and this information helps identify especially susceptible subgroups for specific public health interventions [19]. The same chemical exposure may cause malformations during organogenesis but have no effect or different effects during fetal growth periods.

Q2: How does the concept of cumulative risk apply to chemical mixtures, and what are the current regulatory gaps? Cumulative risk assessment for chemical mixtures addresses the combined risk from exposure to multiple chemicals, which reflects real-world exposure scenarios more accurately than single-chemical assessments. Current chemical management practices under regulations like REACH often do not adequately account for mixture effects, leading to systematic underestimation of actual risks. Scientific research indicates that even when individual chemicals are present at concentrations below safety thresholds, their combined effects can result in significant health and environmental risks [8]. European scientists are now advocating for the inclusion of a Mixture Assessment Factor (MAF) in the revised REACH framework to properly address these cumulative impacts.

Q3: What statistical approaches can help identify critical exposure windows in epidemiological studies? Advanced statistical models like the Bayesian hierarchical distributed exposure time-to-event model can help identify critical exposure windows by estimating the joint effects of exposures during different vulnerable periods. This approach treats preterm birth as a time-to-event outcome rather than a binary outcome, which addresses the challenge of different exposure lengths among ongoing pregnancies [20]. The model allows exposure effects to vary across both exposure weeks and outcome weeks, enabling researchers to determine whether exposures have different impacts at different gestational ages and whether there are particularly sensitive exposure periods.

Q4: What are the limitations of using cumulative exposure as a dose metric in developmental studies? Cumulative exposure (which combines intensity and duration) is not always an adequate parameter when more recent exposure or exposure intensity plays a greater role in disease outcome. If a dose-response relationship is not apparent with cumulative exposure, it might indicate that the exposure metric is inadequate rather than the absence of an effect [21]. This suggests a need for more sophisticated exposure metrics that account for the timing and intensity of exposure relative to critical developmental windows, rather than simply summing total exposure over time.

Q5: How can in vitro methods contribute to identifying critical windows and mixture effects? In vitro assessments can help identify potential mechanisms of disruption to specific cell-signaling and genetic regulatory pathways, which often operate within precise developmental windows. However, these methods have intrinsic limitations: they may not detect toxicants that initiate effects outside the embryo (in maternal or placental compartments), miss effects mediated by physiological changes only present in intact embryos, and lack the dynamic concentration changes and metabolic transformations that occur in vivo [22]. Despite these limitations, they remain valuable for screening and mechanistic studies, particularly when ethical or practical constraints limit in vivo testing.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent findings when examining associations between air pollution exposure during pregnancy and preterm birth risk. Potential Cause: Limitations from standard analytic approaches that treat preterm birth as a binary outcome without considering time-varying exposures over the course of pregnancy. Solution: Implement a discrete-time survival model that treats gestational age as time-to-event data and estimates joint effects of weekly exposures during different vulnerable periods. This approach effectively accommodates differences in exposure length among pregnancies of different gestational ages [20]. Protocol Application:

- Define the risk set starting at the earliest gestational week of interest (e.g., 27th week)

- Model the discrete event hazard rate using appropriate regression (e.g., probit regression)

- Assign dynamic Gaussian process priors to borrow information across exposure weeks and outcome weeks

- Estimate weekly pollutant effects that can be visualized in a matrix format

Problem: Lack of clear dose-response relationship despite overall increased relative risk. Potential Cause: The exposure metric (e.g., cumulative exposure) may not adequately capture the relevant aspect of exposure, especially when more recent exposure or exposure intensity plays a greater role in disease outcome. Solution: Explore alternative exposure metrics and consider that the absence of a dose-response pattern with cumulative exposure might indicate the need for more refined exposure assessment rather than the absence of a true effect [21]. Protocol Application:

- Collect detailed temporal exposure data rather than relying solely on cumulative measures

- Analyze exposure intensity separately from duration

- Consider time-varying exposure models that account for critical periods

- Evaluate whether different exposure metrics yield more consistent dose-response patterns

Problem: Difficulty extrapolating in vitro developmental toxicity results to in vivo outcomes. Potential Cause: Fundamental limitations of in vitro systems, including absence of maternal/placental compartments, lack of physiological changes in intact embryos, and inability to observe functional impairments that manifest postnatally. Solution: Use in vitro methods for appropriate applications such as secondary testing of chemicals with known developmental toxicity potential or mechanistic studies, while recognizing their limitations for primary testing [22]. Protocol Application:

- For secondary testing: Use isolated mammalian embryos and embryonic cells to replicate known in vivo effects

- For mechanistic studies: Employ manipulations possible in vitro (tissue ablation/transplantation, labeling, gene manipulation)

- Clearly define the specific developmental toxicity outcome being assessed

- Validate in vitro findings with targeted in vivo studies when possible

Problem: Inadequate assessment of mixture effects in chemical risk assessment. Potential Cause: Current regulatory frameworks typically assess chemicals individually, assuming people and ecosystems are exposed to them separately rather than in combination. Solution: Advocate for and implement mixture assessment factors in risk assessment frameworks that account for cumulative impacts of hazardous chemicals [8]. Protocol Application:

- Identify co-occurring chemicals in specific exposure scenarios

- Utilize toxicity equivalency factors (TEFs) for chemicals with similar modes of action

- Implement mixture assessment factors to adjust single-chemical risk assessments

- Conduct combined toxicity testing for frequently co-occurring chemical combinations

Table 1: Critical Windows of Exposure for Different Biological Systems

| Biological System | Critical Exposure Windows | Key Outcomes | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory & Immune | Preconceptional, prenatal, postnatal | Asthma, immune dysfunction | [19] |

| Reproductive System | Prenatal, peripubertal | Impaired fertility, structural abnormalities | [19] |

| Nervous System | Prenatal (specific gestational weeks) | Neurobehavioral deficits, cognitive impairment | [19] |

| Cardiovascular & Endocrine | Prenatal, early postnatal | Coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension | [19] |

| Cancer Development | Prenatal, childhood | Various childhood cancers | [19] |

Table 2: Statistical Approaches for Identifying Critical Windows

| Method | Application | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distributed exposure time-to-event model | Preterm birth and air pollution | Estimates joint effects of weekly exposures; allows effects to vary across exposure and outcome weeks | Complex implementation; requires large sample sizes [20] |

| Bayesian hierarchical model | Time-varying environmental exposures | Borrows information across exposure weeks; handles temporal correlation | Computationally intensive [20] |

| Discrete-time survival analysis | Gestational age outcomes | Accommodates different exposure lengths; distinguishes early vs. late outcomes | Requires precise gestational age data [20] |

| Dose-response assessment | Chemical mixture effects | Can incorporate toxicity equivalency factors (TEFs) | May oversimplify complex mixture interactions [22] |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Developmental Timing Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Context | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) | Predicts absorption, distribution, and reactivity | Early screening of chemical potential for developmental toxicity | Must be evaluated for each endpoint of developmental toxicity [22] |

| Mammalian embryo cultures | Ex vivo assessment of developmental effects | Secondary testing of analogs with known developmental toxicity | Lacks maternal and placental compartments [22] |

| Embryonic cell cultures | Cellular and molecular mechanism identification | Analysis of disrupted developmental pathways | Misses tissue-level interactions and physiological changes [22] |

| Toxicity Equivalency Factors (TEFs) | Relates relative toxicity to reference compound | Risk assessment for chemical classes (e.g., dioxins) | Complex when different endpoints have different SARs [22] |

| Biomarkers of exposure | Measures internal dose and early biological effects | Linking specific exposures to developmental outcomes | Requires validation for developmental timing [19] |

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Developmental Toxicity Assessment Pathway

Developmental Toxicity Assessment Workflow

Chemical Mixture Risk Assessment Logic

Chemical Mixture Risk Assessment Logic

Critical Window Analysis Methodology

Critical Window Analysis Methodology

Assessment Frameworks and Computational Tools for Mixture Risk Evaluation

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a whole-mixture and a component-based approach?

The whole-mixture approach evaluates a complex mixture as a single entity, using toxicity data from the entire mixture. This is particularly applicable to mixtures of Unknown or Variable composition, Complex reaction products, or Biological materials (UVCBs). In contrast, the component-based approach estimates mixture effects using data from a subset of individual mixture components, which are then input into predictive mathematical models [23] [24].

FAQ 2: When should I choose a whole-mixture approach for my risk assessment?

Risk assessors generally prefer whole-mixture approaches because they inherently account for all constituents and their potential interactions without requiring assumptions about joint action. This approach is most appropriate when you have adequate toxicity data for your precise mixture of interest or can identify a sufficiently similar mixture with robust toxicity data that can be used as a surrogate [23] [25].

FAQ 3: What does "sufficient similarity" mean and how is it determined?

"Sufficient similarity" indicates that a mixture with adequate toxicity data can be used to evaluate the risk associated with a related data-poor mixture. The determination involves comparing mixtures using both chemical characterization (e.g., through non-targeted analysis) and biological activity profiling (using in vitro bioassays). Statistical and computational approaches then integrate these datastreams to assess relatedness [23] [25].

FAQ 4: Which component-based model should I select for mixtures with different mechanisms of action?

For chemicals that disrupt a common biological pathway but through different mechanisms, dose addition has been demonstrated as a reasonable default assumption. Case studies have shown dose-additive effects for chemicals causing liver steatosis, craniofacial malformations, and male reproductive tract disruption, despite differing molecular initiating events [26]. The Independent Action (IA) model is typically considered for mixtures with components having distinctly different mechanisms and molecular targets [24] [27].

FAQ 5: How can I address chemical interactions in component-based assessments?

The US EPA recommends a weight-of-evidence (WoE) approach that incorporates binary interaction data to modify the Hazard Index. This method considers both synergistic and antagonistic interactions by evaluating the strength of evidence for chemical interactions and their individual concentrations in the mixture [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inadequate toxicity data for my specific complex mixture.

Solution: Implement a sufficient similarity analysis. First, characterize your mixture using non-targeted chemical analysis to create a molecular feature fingerprint. Then, profile biological activity using a battery of in vitro bioassays relevant to your toxicity endpoints. Finally, compare these profiles to well-characterized reference mixtures using multivariate statistical methods or machine learning to identify potential surrogates [23] [25].

Problem: Uncertainties about which chemicals to group together in a component-based assessment.

Solution: Utilize Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) networks to identify logically structured grouping hypotheses. The AOP framework helps map how chemicals with disparate mechanisms of action might converge on common adverse outcomes through different pathways. The EuroMix project has successfully demonstrated this approach for liver steatosis and developmental toxicity [26].

Problem: Evaluating mixture risks for environmental samples with numerous contaminants.

Solution: Apply improved component-based methods that consider all detected chemicals, not just those with established quality standards. Methods include summation of toxic units, mixture toxic pressure assessments based on species sensitivity distributions (msPAF), and comparative use of concentration addition and independent action models. Always combine these with effect-based methods to identify under-investigated emerging pollutants [27].

Problem: Regulatory requirements for common mechanism groups in pesticide risk assessment.

Solution: Follow the weight-of-evidence framework that evaluates structural similarity, physicochemical properties, in vitro bioactivity, and in vivo data. The 2016 EPA Pesticide Cumulative Risk Assessment Framework provides a less resource-intensive screening-level alternative to the full 2002 guidance for establishing common mechanism groups [26].

Problem: Technical challenges in non-targeted analysis for mixture fingerprinting.

Solution: Analyze all test mixtures in parallel under identical laboratory conditions to minimize technical variation. When comparing across studies, leverage emerging universal data standards and reporting guidelines. Remember that full chemical identification isn't always necessary for sufficient similarity assessments; molecular feature signatures (retention time, spectral patterns, relative abundance) often provide sufficient comparative data [23].

Methodological Comparison Table

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Whole-Mixture and Component-Based Approaches

| Aspect | Whole-Mixture Approach | Component-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Toxicity data on the whole mixture or sufficiently similar surrogate | Data on individual components and their potential interactions |

| Regulatory Precedence | Used for diesel exhaust, tobacco smoke, water disinfection byproducts | Common for pesticides with shared mechanisms (organophosphates, pyrethroids) |

| Strengths | Accounts for all components and interactions without additional assumptions; reflects real-world exposure | Can leverage extensive existing data on single chemicals; flexible for various mixture scenarios |

| Limitations | Data for specific mixtures often unavailable; methods for determining sufficient similarity still evolving | May miss uncharacterized components; requires assumptions about joint action (additivity, synergism, antagonism) |

| Ideal Application Context | Complex mixtures with consistent composition (UVCBs); when suitable surrogate mixtures exist | Defined mixtures with known composition; when chemical-specific data are available |

Table 2: Component-Based Models for Mixture Toxicity Assessment

| Model | Principle | Best Application | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration Addition (Dose Addition) | Assumes chemicals act by similar mechanisms or have the same molecular target | Chemicals sharing a common mechanism of action; components affecting the same adverse outcome through similar pathways | May result in significant errors if applied to chemicals with interacting effects |

| Independent Action (Response Addition) | Assumes chemicals act through different mechanisms and at different sites | Mixtures of toxicologically dissimilar chemicals with independent modes of action | Requires complete dose-response data for all components; may underestimate risk for complex mixtures |

| Weight-of-Evidence Approach | Incorporates binary interaction data to modify Hazard Index | When evidence exists for synergistic or antagonistic interactions between mixture components | Requires extensive data on chemical interactions; can be resource-intensive |

| Integrated Addition and Interaction Models | Combines elements of both CA and IA while accounting for interactions | Complex mixtures where some components may interact | Limited validation for higher-order mixtures; increased computational complexity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Resources for Mixtures Risk Assessment Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Chemistry | High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry; Non-Targeted Analysis (NTA) | Comprehensive characterization of complex mixtures; chemical fingerprinting for sufficient similarity assessment |

| Bioactivity Screening | Tox21/ToxCast assay battery; PANORAMIX project methods; Botanical Safety Consortium protocols | High-throughput screening of mixture effects across multiple biological pathways |

| Computational Modeling | Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) regression; Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR); Machine Learning clustering | Identifying mixture patterns in exposure data; evaluating interactions in epidemiological studies |

| Data Integration | Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) networks; TAME (InTelligence and machine LEarning) toolkit | Organizing mechanistic data to form assessment groups; integrating across chemical and biological datastreams |

| Toxicological Reference | Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSD); Environmental Quality Standards (EQS) | Deriving threshold values for ecological risk assessment of mixtures |

| Pyrisoxazole | Pyrisoxazole|CAS 847749-37-5|Fungicide Analytical Standard | Pyrisoxazole is a chiral DMI fungicide for plant pathogen research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| CGP 65015 | CGP 65015, MF:C14H15NO4, MW:261.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting between whole-mixture and component-based approaches

Diagram 2: Methodology for determining sufficient similarity between complex mixtures

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Concentration Addition (CA) and Independent Action (IA)?

A1: The core difference lies in their assumed mechanisms of action [28]:

- Concentration Addition (CA) assumes chemicals in a mixture have a similar mechanism of action and act on the same target site. In this model, one chemical can be considered a dilution of the other, and they can replace each other at a constant ratio to produce the same effect [29] [28].

- Independent Action (IA) assumes chemicals have dissimilar mechanisms of action and act on different target sites. Their effects are considered statistically independent, and the combined effect is calculated based on the probability of each chemical acting on its own target [29] [28].

Q2: When should I use CA over IA, especially if the mechanisms of action are unknown?

A2: From a practical risk assessment perspective, CA is often recommended as a default model. Head-to-head comparisons have shown that even when chemicals have different mechanisms of action, the difference in effect prediction between CA and IA typically does not exceed a factor of five. This makes CA a sufficiently conservative and protective model for many regulatory purposes [29].

Q3: My mixture contains a chemical with high potency but a low maximal effect (low efficacy). Why do my CA and IA predictions fail?

A3: This is a known limitation of both classical models. CA and IA can only predict mixture effects up to the maximal effect level of the least efficacious component. In such cases, the Generalized Concentration Addition (GCA) model, a modification of CA, should be used. The GCA model has proven effective for predicting full dose-response curves for mixtures containing constituents with low efficacy [29].

Q4: Can these models handle mixtures where some chemicals stimulate an effect while others inhibit it?

A4: No, this presents a significant challenge. The CA, IA, and GCA models are generally not applicable when mixture components exert opposing effects (e.g., some increase hormone production while others decrease it). In such situations, no valid predictions can be performed with these standard models, and biology-based approaches may be required [29].

Q5: The combined effect of my mixture changes over time and differs between endpoints (e.g., growth vs. reproduction). Why does this happen?

A5: Descriptive models like CA and IA cannot explain temporal changes or differences between endpoints because they lack a biological basis. These observations are often due to physiological interactions within the organism. For example, a chemical affecting growth will subsequently alter body size, which can impact feeding rates, toxicokinetics, and energy allocation to reproduction. To understand and predict these dynamics, biology-based approaches like Dynamic Energy Budget (DEB) theory are necessary [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or unpredictable mixture effects are observed.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Interactions | Review literature for known chemical interactions (e.g., bioavailability modification, shared biotransformation pathways). | Incorporate toxicokinetic data to account for interactions affecting uptake and metabolism [30]. |

| Opposing Effects of Components | Analyze single-chemical dose-response curves to determine if effects are in opposite directions. | Standard models (CA/IA) are invalid. Consider mechanistic or biology-based modeling approaches [29]. |

| Low-Efficacy Components | Check if any single chemical fails to reach 100% effect, even at high concentrations. | Apply the Generalized Concentration Addition (GCA) model instead of classic CA or IA [29]. |

| Temporal Effect Dynamics | Analyze effects at multiple time points for the same endpoint. | Move beyond descriptive models. Adopt a biology-based framework like DEBtox to model energy allocation over time [30]. |

Problem: Determining which model (CA vs. IA) to apply.

Follow this decision logic to select the appropriate model:

Experimental Protocol: Validating Models with H295R Steroidogenesis Assay

This protocol outlines a methodology for testing CA, IA, and GCA models using an in vitro system that measures effects on steroid hormone synthesis [29].

Cell Culture and Seeding

- Cell Line: NCI-H295R human adrenocortical carcinoma cells.

- Culture Conditions: Maintain cells in DMEM/F12 medium (without phenol red) supplemented with 2.5% Nu-Serum and 1% ITS+ (insulin, transferrin, selenous acid) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [29].

- Seeding: Seed cells into 24-well plates at a density of 3×10ⵠcells per well and allow them to attach for 24 hours [29].

Mixture Design and Dosing

Two common mixture designs are used:

- Fixed-Ratio Design: The ratio of individual chemicals in the mixture is kept constant, while the total concentration of the mixture is varied [29].

- Potency-Adjusted Mixture: The ratios are adjusted so that each component contributes an equal effect based on prior knowledge (e.g., NOAELs from mammalian studies) [29].

- Exposure: Apply single chemicals and the designed mixtures to the cells across a concentration range (e.g., 0.04 to 30 µM). Include a solvent control. Incubate for 48 hours [29].

Endpoint Measurement

- Hormone Analysis: Collect supernatant after 48h. Analyze steroid hormones (e.g., progesterone, testosterone, estradiol) using sensitive methods like LC-MS/MS [29].

- Viability Assay: Perform a concurrent cytotoxicity assay (e.g., MTT assay) to ensure that observed effects are not due to general cytotoxicity [29].

Data Analysis and Model Prediction

- Single-Chemical Curves: Fit dose-response models to the data for each individual chemical.

- Model Prediction: Use the single-chemical parameters to calculate the predicted mixture effect using the CA, IA, and GCA models.

- Validation: Compare the model predictions to the experimentally observed mixture effect to assess the accuracy of each model.

The following workflow visualizes the key steps of the experimental protocol and analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| H295R Cell Line | An in vitro model system for investigating the effects of chemicals and mixtures on steroid hormone synthesis [29]. | Used to test mixtures of pesticides and environmental chemicals on progesterone, testosterone, and estradiol production [29]. |

| Luminescent Bacteria (e.g., A. fischeri) | A prokaryotic bioassay for rapid, cost-effective acute toxicity testing of single chemicals and mixtures [31]. | Applied in the Microtox system to assess the toxicity of wastewater, river water, and other environmental samples [31]. |

| Mixtox R Package | An open-access software tool that provides a common framework for curve fitting, mixture experimental design, and mixture toxicity prediction using CA, IA, and other models [28]. | Enables researchers to perform computational predictions of mixture toxicity without requiring extensive programming expertise [28]. |

| Fixed-Ratio Mixture | A mixture design where the relative proportions of components are kept constant. Used to test the predictability of mixture effect models [29]. | A "real-world" mixture of 12 environmental chemicals was tested in H295R cells, with ratios based on typical human exposure levels [29]. |

| YM-341619 | YM-341619, MF:C22H21F3N6O2, MW:458.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Diperamycin | Diperamycin, MF:C38H64N8O14, MW:857.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in leveraging advanced computational tools for chemical mixture risk assessment. The content focuses on two primary toolboxes: the Mixture Risk Assessment (MRA) Toolbox and the OECD QSAR Toolbox, framing their use within the broader context of chemical mixture effects research. These platforms support the paradigm shift from single-substance to mixture-based risk assessment and from animal testing to alternative testing strategies, as mandated by modern chemical regulations like REACH.

Core Toolbox Features and Specifications

The MRA Toolbox is a novel, web-based platform (https://www.mratoolbox.org) that supports mixture risk assessment by integrating different prediction models and public databases. Its integrated framework allows assessors to screen and compare the toxicity of mixture products using different computational techniques and find strategic solutions to reduce mixture toxicity during product development [32].

Key Specifications:

- System Architecture: Built on Community Enterprise Operating System (CentOS) v. 8.3, with Java Server Pages for graphical user interfaces, and MariaDB v. 10.3.27 for database management [32].

- Core Predictive Models: Implements four additive toxicity models [32]:

- Conventional Models (Lower-tier): Concentration Addition (CA) and Independent Action (IA)

- Advanced Models (Higher-tier): Generalized Concentration Addition (GCA) and QSAR-Based Two-Stage Prediction (QSAR-TSP)

- Data Handling: Features dual data saving modes to ensure user data confidentiality and security, and interfaces with PubChem DB for chemical properties search [32].

The OECD QSAR Toolbox is a software application designed to fill gaps in (eco)toxicity data needed for assessing the hazards of chemicals. It provides a systematic workflow for grouping chemicals into categories and using existing experimental data to predict the properties of untested chemicals [33].

Key Features (Version 4.8):

- Key Functionalities: Profiling, data collection, category definition, and data gap filling [33].

- Training Resources: Extensive video tutorials (over 40 available) covering areas such as installing the Toolbox, defining target endpoints, profiling chemicals, collecting data, and using metabolism in predictions [33].

- Regulatory Framework: Supports the (Q)SAR Assessment Framework (QAF), including the (Q)SAR model reporting format (QMRF) and (Q)SAR prediction reporting format (QPRF) [33].

Technical Reference Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Predictive Models in the MRA Toolbox

| Model Name | Type | Underlying Principle | Typical Application | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration Addition (CA) [32] | Conventional (Lower-tier) | Sum of effect concentrations | Substances with similar Modes of Action (MoAs) | Conservative default for mixture risk assessments; simpler to use |

| Independent Action (IA) [32] | Conventional (Lower-tier) | Sum of biological responses | Substances with dissimilar Modes of Action (MoAs) | Requires MoA data for all components |

| Generalized Concentration Addition (GCA) [32] | Advanced (Higher-tier) | Extension of CA | Chemical substances with low toxicity effects | Addresses limitations of CA for low-effect components |

| QSAR-Based Two-Stage Prediction (QSAR-TSP) [32] | Advanced (Higher-tier) | Integrates CA and IA via QSAR | Mixture components with different MoAs | Uses machine learning to cluster chemicals by structural similarity and estimate MoAs |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Mixture Assessment

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Experimentation | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|

| PubChem Database [32] | Provides essential chemical property data (name, CAS, structure, MW) for input into predictive models. | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| Dose-Response Curve (DRC) Equations [32] | Mathematical functions (17 available in MRA Toolbox) used to fit experimental data and define toxicity parameters for single substances. | Implemented in the 'mixtox' R package within the MRA Toolbox. |

| Chemical Mixture Calculator [32] | A probabilistic tool for assessing risks of combined dietary and non-dietary exposures; used for comparative analysis. | http://www.chemicalmixturecalculator.dk |

| Monte Carlo Risk Assessment (MCRA) [32] | A probabilistic model for cumulative exposure assessments and risk characterization of mixtures. | https://mcra.rivm.nl |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: When should I use the advanced models (GCA or QSAR-TSP) over the conventional models (CA or IA) in the MRA Toolbox?

A: The advanced models are particularly useful in specific scenarios [32]:

- GCA Model: Apply when dealing with chemical substances that have low toxic effects, where the conventional CA model may be less accurate.

- QSAR-TSP Model: Use when your mixture contains components with different or unknown Modes of Action (MoAs), as this model uses a chemical clustering method based on machine learning and structural similarities to estimate MoAs.

Q2: My mixture components have unknown MoAs. Which model is most appropriate, and why?

A: The QSAR-TSP model is specifically designed for this challenge. It was developed to predict the toxicity of mixture components with different MoAs by applying a chemical clustering method based on machine learning techniques and structural similarities among the substances to estimate their MoAs [32]. It then integrates both CA and IA concepts for the final prediction, making it superior to CA or IA alone when MoA data is lacking.

Q3: The MRA Toolbox cannot calculate the full dose-response curve for my mixture. What could be the cause?

A: This issue can arise when there is a toxic effect of mixture components at certain higher concentrations. The toolbox has a built-in function to handle this: Automatic determination of predictable DRC ranges. This function enables the toolbox to estimate the mixture toxicity within the available effect range of low-toxic components by automatically selecting a concentration section where a calculation is possible [32].

Q4: Where can I find comprehensive training materials for the OECD QSAR Toolbox?

A: The official QSAR Toolbox website hosts extensive resources [33]:

- Manuals: Including Installation, Getting Started, and Multi-User Server manuals for version 4.8.

- Video Tutorials: Over 40 tutorials covering input, profiling, data gap filling, reporting, metabolism, and automated workflows.

- Webinars: ECHA and other webinars on regulatory applications and new developments.

Q5: How does the MRA Toolbox ensure the confidentiality of my proprietary chemical data?

A: The MRA Toolbox is designed with dual data saving modes to ensure user data confidentiality and security [32]. This allows you to work on proprietary mixture formulations with greater confidence, a crucial feature for product development.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Predicting Mixture Toxicity Using the MRA Toolbox

This protocol outlines the methodology for using the MRA Toolbox to calculate the toxicity of a chemical mixture, based on the case studies presented in its development paper [32].

1. Input Preparation:

- Gather the chemical identities (names or CAS numbers) and their respective concentrations in the mixture.

- For each component, obtain or derive toxicity data. This can be:

- An experimental half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) value.

- A full dose-response curve (DRC).

- For components without data, use the integrated PubChem DB interface to search for properties [32].

2. Toolbox Configuration:

- Log in to the web platform at https://www.mratoolbox.org [32].

- Input the prepared chemical and toxicity data.

- Select the predictive models to run. For a comprehensive analysis, select all four models (CA, IA, GCA, QSAR-TSP) to compare their outputs [32].

3. Execution and Analysis:

- Run the prediction. The toolbox will automatically compare the estimated mixture toxicity using all selected models [32].

- Review the results. The toolbox provides new functional values for easily screening and comparing the toxicity of mixture products using different computational techniques [32].

- Use the comparison to inform strategic solutions to reduce the mixture toxicity in the product development process [32].

Workflow: Data Gap Filling with the OECD QSAR Toolbox

This workflow summarizes the standard procedure for using the OECD QSAR Toolbox to fill data gaps for a target chemical, as indicated in its video tutorials and supporting documentation [33].

Title: QSAR Toolbox Data Gap Filling Workflow

Advanced Technical Diagrams

Title: MRA Toolbox System Architecture

Title: Mixture Toxicity Prediction Logic

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)