From Data to Decision: A Modern Statistical Analysis Framework for Ecotoxicology

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the statistical analysis of ecotoxicity data, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

From Data to Decision: A Modern Statistical Analysis Framework for Ecotoxicology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the statistical analysis of ecotoxicity data, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of ecotoxicology and the purpose of statistical analysis, explores the shift from traditional hypothesis testing to modern regression-based methods like ECx and benchmark dose (BMD), and addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and experimental design optimizations. The content also delves into validation techniques, comparative analyses of statistical software, and the application of advanced models including Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) and Bayesian frameworks to ensure robust and reproducible results in environmental risk assessment.

The Bedrock of Ecotoxicology: Understanding Organisms, Endpoints, and Statistical Purpose

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the ECOTOX Knowledgebase and how can it support my research? A: The ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX) is the world's largest compilation of curated ecotoxicity data, providing single chemical ecotoxicity data for over 12,000 chemicals and ecological species with over one million test results from over 50,000 references. It supports chemical safety assessments and ecological research through systematic, transparent literature review procedures, offering reliable curated ecological toxicity data for chemical assessments and research [1].

Q: My research involves sediment toxicity tests. When should I use natural field-collected sediment versus artificially formulated sediment? A: Using natural field-collected sediment contributes to more environmentally realistic exposure scenarios and higher well-being for sediment-dwelling organisms. However, it lowers comparability and reproducibility among studies due to differences in base sediment characteristics. Artificially formulated sediment, recommended by some OECD guidelines, provides higher homogeneity but may negatively impact natural behavior, feeding, reproduction, and survival of test organisms, potentially deviating from natural contaminant fate and bioavailability [2].

Q: Why is there a current push to update statistical guidance in ecotoxicology, such as OECD No. 54? A: Standardized methods and guidelines are still largely based on statistical principles and approaches that can no longer be considered state-of-the-art. A revision of documents like OECD No. 54 is needed to better reflect current scientific and regulatory standards, incorporate modern statistical practices in hypothesis testing, provide clearer guidance on model selection for dose-response analyses, and address methodological gaps for data types like ordinal and count data [3] [4].

Troubleshooting Experimental Protocols

Issue: Inconsistent results in sediment ecotoxicity tests

Solution: Follow these six key recommendations for using natural field-collected sediment [2]:

- Collection Site: Collect natural sediment from a well-studied site, historically and through laboratory analysis of background contamination.

- Storage: Collect larger quantities of sediment and store them prior to experiment initiation to ensure a uniform sediment base.

- Characterization: Characterize sediment used in testing for, at minimum, water content, organic matter content, pH, and particle size distribution.

- Spiking Method: Select spiking method, equilibration time, and experimental setup based on contaminant properties and the specific research question.

- Controls: Include a control sediment treated similarly to the spiked sediment and a solvent control when appropriate.

- Exposure Confirmation: Quantify experimental exposure concentrations in the overlying water, porewater (if applicable), and bulk sediment at the beginning and end of each experiment.

Key Data and Reagents

| Metric | Data Volume |

|---|---|

| Number of Chemicals | > 12,000 |

| Number of Ecological Species | > 12,000 |

| Number of Test Results | > 1,000,000 |

| Number of References | > 50,000 |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Ecotoxicology |

|---|---|

| Natural Field-Collected Sediment | Provides environmentally realistic exposure scenarios for benthic organisms and improves organism well-being during testing [2]. |

| Artificially Formulated Sediment | Offers a theoretically homogeneous substrate, as recommended by some standard guidelines (e.g., OECD), though may lack ecological realism [2]. |

| Control Sediment | Serves as a baseline for comparing effects in spiked or contaminated sediments, essential for validating test results [2]. |

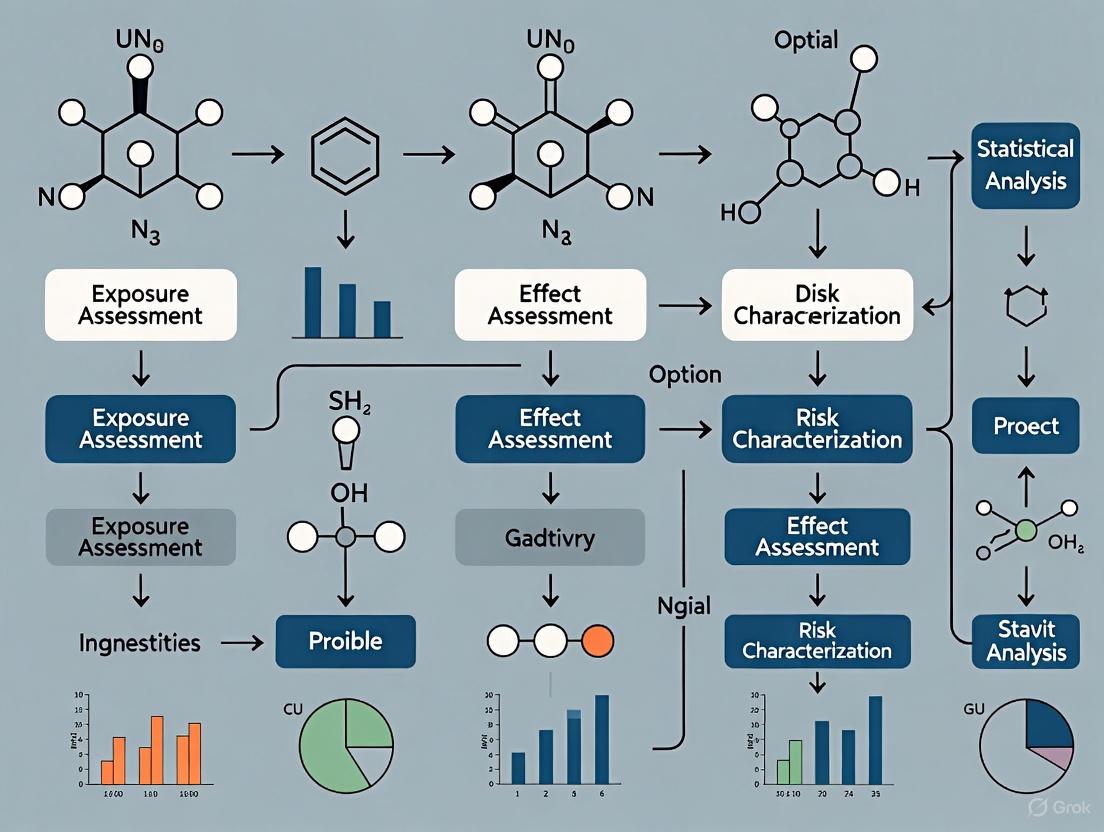

Experimental Workflow and Statistical Analysis Diagrams

Research Workflow

Statistical Analysis Flow

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What defines an environmental compartment in ecotoxicology studies? A: An environmental compartment is a part of the physical environment defined by a spatial boundary, such as the atmosphere, soil, surface water, sediment, or biota. The behavior and fate of chemical contaminants are determined by the properties of these compartments and the physicochemical characteristics of the chemicals themselves [5].

Q: Why is the selection of key test organisms critical? A: Key test organisms serve as biological indicators for the health of an entire environmental compartment. Their response to a stressor, such as a chemical contaminant, provides vital data on potential toxic effects, which is then analyzed using statistical flowcharts to determine ecological risk [5].

Q: How do I choose the right test organism for a sedimentary system? A: The choice depends on the research question, the contaminant's properties, and the organism's ecological relevance. Benthic organisms like midge larvae (e.g., Chironomus riparius) or oligochaete worms are often selected because they live in and interact closely with sediments, providing direct exposure pathways [5].

Q: A common issue is low statistical power in my ecotoxicological tests. What could be the cause? A: Low statistical power can stem from high variability in the test organism's response, an insufficient number of replicates, or an exposure concentration that is too low to elicit a measurable effect above background noise. Review your experimental design and ensure your sample size is adequate for the expected effect size.

Q: My control groups are showing unexpected effects. How should I troubleshoot this? A: Unexpected control group effects suggest contamination of the control medium, unsuitable environmental conditions (e.g., dissolved oxygen, temperature), or that the test organisms were not properly acclimated. Verify the purity of your control water, sediments, and food, and meticulously document all holding and acclimation conditions.

Experimental Protocols for Key Test Organisms

Aquatic Compartment: Acute Toxicity Test withDaphnia magna

Principle: This test assesses the acute immobilization of the freshwater cladoceran Daphnia magna after 48 hours of exposure to a chemical substance or effluent, providing a standard metric for aquatic toxicity (EC50).

Methodology:

- Test Organism: Use young, neonatal Daphnia magna (< 24 hours old) from healthy laboratory cultures.

- Test Medium: Reconstituted standard freshwater (e.g., ISO or OECD standard) with a controlled pH, hardness, and temperature.

- Exposure: A minimum of five test concentrations and a control are required, each with multiple replicates (e.g., 4 beakers per concentration). Each replicate contains a specified number of daphnids (e.g., 5) in a defined volume of test solution.

- Conditions: Maintain a constant temperature (18-22°C) and a photoperiod of 16 hours light:8 hours dark for the 48-hour test duration. Do not feed the organisms during the test.

- Endpoint Measurement: Record the number of immobile (non-swimming) daphnids in each beaker at 48 hours.

- Data Analysis: The percentage of immobile organisms at each concentration is calculated, and the EC50 (the concentration that immobilizes 50% of the test organisms) is determined using statistical probit analysis or logistic regression.

Sedimentary Compartment: Bioaccumulation Test withLumbriculus variegatus

Principle: This test determines the potential for a chemical to accumulate in the aquatic oligochaete Lumbriculus variegatus from spiked sediment, yielding a biota-sediment accumulation factor (BSAF).

Methodology:

- Test Organism: Use Lumbriculus variegatus of a specific size range from a synchronized laboratory culture.

- Sediment Spiking: A known quantity of the test chemical is thoroughly mixed into a standardized, uncontaminated natural or formulated sediment. The spiked sediment is then conditioned for a period (e.g., 28 days) to allow for equilibration.

- Exposure: Introduce a known number of worms into beakers containing the spiked sediment and overlying water. Include control sediments spiked only with the carrier solvent.

- Conditions: Maintain a constant temperature and aerate the overlying water gently. A 28-day exposure period is common, followed by a 24-hour depuration period in clean water to clear the gut contents.

- Sample Analysis: After depuration, the worms are collected, and the tissue concentration of the test chemical is measured. Parallel samples of the sediment are also analyzed to determine the chemical concentration.

- Data Analysis: The BSAF is calculated as the ratio of the chemical concentration in the worm tissue (lipid-normalized) to the concentration in the sediment (organic carbon-normalized).

Terrestrial Compartment: Reproduction Test withEisenia fetida

Principle: This test evaluates the effect of a chemical on the reproduction and survival of the earthworm Eisenia fetida in an artificial soil substrate.

Methodology:

- Test Organism: Use adult earthworms (Eisenia fetida) with a well-developed clitellum.

- Soil Spiking: The test chemical is mixed into a standardized artificial soil (e.g., a mix of sand, kaolinite clay, peat, and calcium carbonate). Multiple concentrations are prepared.

- Exposure: Introduce a specified number of adult worms (e.g., 10) into containers holding the spiked soil. The test runs for 4 weeks, during which the worms are fed a controlled amount of food.

- Conditions: Maintain containers in constant darkness at a defined temperature (e.g., 20°C) and soil moisture content.

- Endpoint Measurement: Adult survival is assessed at the end of the 4 weeks. The number of juvenile worms produced is determined by carefully washing the soil contents through a sieve.

- Data Analysis: The results are used to calculate the EC50 for reproduction inhibition (the concentration that reduces the number of juveniles by 50%) and the NOEC (No Observed Effect Concentration) using statistical analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Statistical Analysis Workflow for Ecotoxicology Research

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for the statistical analysis of data from ecotoxicology experiments, from raw data to interpretation.

Statistical Analysis Flowchart

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Ecotoxicology |

|---|---|

| Reconstituted Freshwater | A standardized, chemically defined water medium used in aquatic toxicity tests (e.g., with Daphnia or algae) to ensure reproducibility and eliminate confounding variables from natural water sources. |

| Formulated Sediment | A synthetic sediment with a standardized composition of sand, silt, clay, and organic carbon. It is used in sediment toxicity tests to provide a consistent and reproducible substrate for spiking with contaminants. |

| Artificial Soil | A standardized soil mixture used in terrestrial earthworm tests. Its defined composition allows for the accurate dosing of test chemicals and ensures that results are comparable across different laboratories. |

| Positive Control Substances | Reference toxicants, such as potassium dichromate (for Daphnia) or chloracetamide (for earthworms), used to verify the sensitivity and health of the test organisms. A successful test requires the positive control to produce a predictable toxic response. |

| Carrier Solvents | Substances like acetone or dimethyl formamide (DMF) are used to dissolve poorly water-soluble test chemicals before they are introduced into the test medium. The solvent concentration must be minimized and consistent across all treatments, including a solvent control. |

| Isofebrifugine | Isofebrifugine, MF:C16H19N3O3, MW:301.34 g/mol |

| Chrolactomycin | Chrolactomycin, MF:C24H32O7, MW:432.5 g/mol |

Conceptual Foundations and FAQs

Q1: What is a surrogate endpoint, and why is it used in ecotoxicology and drug development? A surrogate endpoint is a biomarker or measurement that is used as a substitute for a direct measure of how a patient feels, functions, or survives (in medicine) or for a measure of overall ecological fitness (in ecotoxicology). They are used because they can often be measured more easily, frequently, or cheaply than the true endpoint of ultimate interest [6]. According to the FDA, a surrogate endpoint is "a marker... that is not itself a direct measurement of clinical benefit," but that is known or reasonably likely to predict that benefit [7].

Q2: What are the key criteria for a valid surrogate endpoint? A valid surrogate should be consistently measurable, sensitive to the intervention, and on the causal pathway to the true endpoint. Most importantly, a change in the surrogate endpoint caused by an intervention must reliably predict a change in the hard, true endpoint (e.g., survival, population viability) [6].

Q3: Why might a surrogate endpoint like growth or reproduction fail to predict overall fitness? Surrogates can fail for several reasons, as seen in clinical medicine:

- Pleiotropic Effects: The experimental treatment may affect multiple biological pathways. While it improves the surrogate, it might have unrelated harmful effects. For example, a drug may reduce tumor size (a surrogate) but increase fatal infections through immune suppression, negating any survival benefit [6].

- Lack of Causality: The surrogate may be correlated with, but not causally on the pathway to, the true endpoint. For example, suppressing premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) after a heart attack did not reduce mortality, even though PVCs predict higher mortality [6].

- Heterogeneous Populations: The surrogate may work well in one subpopulation but not in another. In myeloma trials, the surrogate "progression-free survival" (PFS) predicted overall survival well in most patients, but not in a specific genetic subgroup, where an improvement in PFS was paradoxically linked to worse survival [8].

Q4: How are surrogate endpoints regulated for drug approval? The FDA maintains a "Table of Surrogate Endpoints" that have been used as the basis for drug approval. This includes endpoints like "Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1)" for asthma/COPD and "Reduction in amyloid beta plaques" for Alzheimer's disease (under accelerated approval) [7]. This demonstrates that with sufficient validation, surrogates are critical for accelerating the development of new therapies.

Experimental Protocols for Endpoint Analysis

This section outlines standard methodologies for measuring core endpoints in ecotoxicology, framed within a statistical analysis workflow.

Protocol for Survival Analysis (e.g., in Acute Toxicity Testing)

Objective: To determine the lethal effects of a stressor over a specified duration. Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Organisms are randomly assigned to several concentrations of a toxicant and a control group. Each group is replicated.

- Exposure & Monitoring: Organisms are exposed under controlled conditions (temperature, pH, light). Mortality is recorded at regular intervals (e.g., 24h, 48h, 96h). Organisms are not fed during short-term tests.

- Data Collection: The primary data is the number of dead organisms in each replicate at each observation time.

- Statistical Analysis: Data are analyzed using Probit Analysis or Logistic Regression to calculate LC50 values (Lethal Concentration for 50% of the population) and their confidence intervals. Time-to-event data can be analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Cox Proportional Hazards models [9].

Protocol for Reproduction Analysis (e.g., in Chronic Life-Cycle Tests)

Objective: To assess the sublethal effects of a stressor on reproductive output and success. Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Organisms (e.g., daphnids, fish) are exposed to sublethal concentrations of a toxicant through all or part of their life cycle, including reproductive maturity.

- Exposure & Monitoring: Tests are longer-term (e.g., 21 days for Daphnia). Endpoints include the number of offspring produced per female, number of broods, time to first reproduction, and egg viability.

- Data Collection: Daily counts of offspring are typical. For fish, egg counts and hatch rates are recorded.

- Statistical Analysis: Data are often analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc tests to compare means between treatment groups. If data violates assumptions of normality, non-parametric tests (e.g., Kruskal-Wallis) are used. Reproduction data is often a key input for population modeling [9].

Protocol for Growth Analysis

Objective: To quantify the effects of a stressor on energy acquisition and allocation towards somatic growth. Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Similar to reproduction tests, organisms are exposed to sublethal concentrations over a defined period.

- Exposure & Monitoring: Organisms are measured (e.g., length, weight) at the beginning and end of the exposure period. Interim measurements may also be taken.

- Data Collection: The primary data is the change in body size (length or weight) per unit time.

- Statistical Analysis: Growth rates are analyzed using ANOVA. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) can be used with initial size as a covariate. Model II regression is appropriate when comparing the scaling of different growth metrics [9].

The Statistical Analysis Workflow in Ecotoxicology

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow from experimental data to the interpretation of fitness surrogates, incorporating key statistical decision points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and concepts used in experiments involving fitness surrogates.

| Item/Concept | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Test Organisms (e.g., Daphnia magna, Danio rerio, Chironomus riparius) | Standardized biological models with known life histories. Their responses to toxicants in survival, growth, and reproduction tests are used to extrapolate potential ecological effects [9]. |

| LC50 / EC50 | A quantitative statistical estimate of the concentration of a toxicant that is lethal (LC50) or causes a specified effect (EC50, e.g., immobility) in 50% of the test population after a specified exposure time. It is a fundamental endpoint for comparing toxicity [9]. |

| NOEC / LOEC | The No Observed Effect Concentration (NOEC) and the Lowest Observed Effect Concentration (LOEC) are statistical estimates identifying the highest concentration causing no significant effect and the lowest concentration causing a significant effect, respectively, compared to the control [9]. |

| Progression-Free Survival (PFS) | A clinical surrogate endpoint defined as the time from the start of treatment until disease progression or death. It is commonly used in oncology trials (e.g., myeloma) as a surrogate for overall survival, though its validity can be context-dependent [8]. |

| Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) | A highly sensitive biomarker used in hematologic cancers (e.g., multiple myeloma) to detect the small number of cancer cells remaining after treatment. It is an emerging surrogate endpoint for accelerated drug approval [8]. |

| Nitrofurantoin Sodium | Nitrofurantoin Sodium|Research-Chemical |

| STL427944 | STL427944|FOXM1 Inhibitor|Research Compound |

Causal Pathways Linking Surrogates to Fitness

The relationship between a surrogate and the true endpoint is strongest when the surrogate lies on the causal pathway. The following diagram contrasts valid and invalid causal pathways for common surrogates.

In ecotoxicology, statistical analysis transforms raw data from tests on organisms into summary criteria that quantify a substance's toxic effect. The most common criteria are the No Observed Effect Concentration (NOEC), the Lowest Observed Effect Concentration (LOEC), and Effect Concentration (ECx) values [10] [11].

Q: What is the fundamental difference between the NOEC/LOEC approach and the ECx approach?

A: The key difference lies in their underlying methodology. NOEC and LOEC are determined via hypothesis testing (comparing treatments to a control), while ECx values are derived via regression analysis (modeling the entire concentration-response relationship) [10].

The following table summarizes the definitions and characteristics of these key endpoints.

| Summary Criterion | Full Name & Definition | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| NOEC [10] [11] | No Observed Effect Concentration: The highest tested concentration at which there is no statistically significant effect (p < 0.05) compared to the control group. | - Dependent on the specific concentrations chosen for the test.- Does not provide an estimate of the effect at that concentration.- Does not include confidence intervals or measures of uncertainty. |

| LOEC [10] [11] | Lowest Observed Effect Concentration: The lowest tested concentration that produces a statistically significant effect (p < 0.05) compared to the control group. | - The concentration immediately above the NOEC.- Like NOEC, its value is constrained by the experimental design. |

| ECx [10] [11] | Effect Concentration for x% effect: The concentration estimated to cause a given percentage (x%) of effect (e.g., 10%, 50%) relative to the control. It is derived from a fitted concentration-response model. | - Utilizes data from all test concentrations.- Provides a specific estimate of the effect level.- Allows for the calculation of confidence intervals to express uncertainty. A common variant is the EC10. |

| MATC [11] | Maximum Acceptable Toxicant Concentration: The geometric mean of the NOEC and LOEC (MATC = √(NOEC × LOEC)). It represents a calculated "safe" concentration. | - Can be used to derive a NOEC if only the MATC is reported (NOEC ≈ MATC / √2). |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Statistical Issues

Q: My LOEC is the lowest concentration I tested. What is my NOEC, and how can I report this properly?

A: In this case, the NOEC is technically undefined because there is no tested concentration below the LOEC [10]. This is a major limitation of the NOEC/LOEC approach. In risk assessment, a common workaround is to apply a conversion factor if the effect level at the LOEC is known. For instance, if the LOEC has an effect between 10% and 20%, it is sometimes approximated that NOEC = LOEC / 2 [11]. However, you should clearly state this assumption in your reporting. This problem highlights an advantage of the ECx approach, which can estimate low-effect concentrations even if they fall between tested doses [10].

Q: Regulatory guidelines are moving away from NOEC/LOEC. Why, and what are the main criticisms?

A: Regulatory bodies like the OECD have recommended a shift towards regression-based ECx values due to several critical disadvantages of the NOEC/LOEC approach [10]:

- Potential to Mislead: The term "No Observed Effect" can be misinterpreted as "No Effect," when it merely means no statistically significant effect was detected in that specific test design [10].

- No Estimate of Uncertainty: NOEC/LOEC values are simple test concentrations and do not come with confidence intervals, giving a false impression of certainty [10].

- Inefficient Use of Data: They ignore the information contained in the full concentration-response curve, using only a limited amount of the data generated by the test organisms [10].

- Dependence on Test Design: Their values are highly sensitive to the number and spacing of the concentration groups chosen by the experimenter [10].

Q: Are there valid reasons to still use NOEC/LOEC?

A: Yes, some scientists argue that a blanket ban on NOEC/LOEC is misguided. There are real-world scenarios where hypothesis testing (NOEC/LOEC) is more appropriate than regression-based ECx estimation [12]. For example, ECx models may not be suitable for all types of data or may offer no practical advantage in certain situations. The key is a thoughtful consideration of study design and the choice of the most meaningful statistical approach for the specific research question [12].

Essential Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chronic Ecotoxicity Test Workflow

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for a chronic ecotoxicity study, from design to data analysis.

Detailed Methodology for Key Experiments

A standard chronic ecotoxicity test, such as those aligned with OECD guidelines, follows a structured protocol [10] [9]:

- Test Organism and System Setup: Select relevant species (e.g., algae, daphnids, fish). Prepare a dilution series of the test substance and a control medium. Each concentration and the control should have multiple replicates (e.g., 3-4) to account for biological variation.

- Exposure and Monitoring: Randomly assign organisms to each test chamber. Maintain controlled environmental conditions (temperature, light, pH) throughout the exposure period. Renew test solutions periodically if it is a static-renewal or flow-through test.

- Endpoint Measurement: At test termination, measure predefined sublethal endpoints. For growth, measure the length or weight of surviving organisms. For reproduction, count the number of offspring produced per parent organism.

- Data Collection and Preparation: Compile raw data for statistical analysis. Calculate the mean response for each replicate and check data for normality and homogeneity of variance, which are assumptions for many statistical tests.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions in standard ecotoxicity testing.

| Item/Category | Function in Ecotoxicity Testing |

|---|---|

| Reference Toxicants | A standard chemical (e.g., potassium dichromate, copper sulfate) used to validate the health and sensitivity of the test organisms. A test is considered valid if the EC50 for the reference toxicant falls within an expected range. |

| Culture Media | Synthetic water or soil preparations that provide essential nutrients for maintaining healthy cultures of the test organisms (e.g., algae, daphnia) before and during the assay. |

| Dilution Water | A standardized, clean water medium (e.g., reconstituted hard or soft water per OECD standards) used to prepare accurate dilution series of the test substance. |

| Solvents / Carriers | A small amount of a non-toxic solvent (e.g., acetone, dimethyl formamide) may be used to dissolve a water-insoluble test substance. A solvent control must be included in the experimental design. |

| Gilvusmycin | Gilvusmycin, MF:C38H34N6O8, MW:702.7 g/mol |

| Pacidamycin D | Pacidamycin D, MF:C32H41N9O10, MW:711.7 g/mol |

Visualization and Color Contrast Guidelines for Scientific Diagrams

Creating clear and accessible visualizations is critical for scientific communication. The following guidelines ensure your diagrams are readable by everyone, including those with visual impairments.

Accessible Color Palette for Scientific Figures

The palette below is designed for high clarity and adheres to accessibility principles [13] [14].

| Color Name | HEX Code | Use Case & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Blue | #4285F4 |

Primary data series, main flow. |

| Red | #EA4335 |

Highlighting significant effects, LOEC, or warnings. |

| Yellow | #FBBC05 |

Secondary data series, cautionary notes. Ensure text on this background is dark (#202124). |

| Green | #34A853 |

Control groups, "no effect" indicators, safe thresholds. |

| White | #FFFFFF |

Diagram background. |

| Light Grey | #F1F3F4 |

Node backgrounds, section shading. |

| Dark Grey | #5F6368 |

Borders, secondary lines. |

| Black | #202124 |

Primary text color for high contrast against light backgrounds. |

Key Color Contrast Rules

All visual elements must meet the following Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) for contrast [15] [13]:

- Normal Text: A contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 between the text color and its background color.

- Large-Scale Text (18pt+ or 14pt+bold): A contrast ratio of at least 3:1 [13].

- User Interface Components and Graphical Objects: A contrast ratio of at least 3:1 against adjacent colors [13].

Critical Rule for DOT Scripts: When defining a node in your diagram, explicitly set both the fillcolor (background) and fontcolor to ensure high contrast. For example, for a yellow node, use dark text: [fillcolor="#FBBC05" fontcolor="#202124"].

Integrating Physicochemical Properties to Identify Relevant Environmental Compartments

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

Data Compilation and Curation

Q: What are the minimal reporting requirements for test compound properties to ensure data reusability?

A transparent and detailed reporting of the test compound is fundamental. Your methodology should include [16]:

- Source and Purity: The commercial source, lot number, and stated purity of the test substance.

- Chemical Characterization: Information on the chemical composition, including the presence and concentration of known impurities or additives.

- Verification: Details of any analytical methods used to verify the chemical identity and concentration of the test substance before and during the experiment.

- Critical Properties: Key physicochemical properties such as water solubility, vapor pressure, octanol-water partition coefficient (Log Kow), and dissociation constant (pKa). Summarize these for easy comparison in your reports [16]:

| Property | Description | Importance in Compartment Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Water Solubility | The maximum amount of a chemical that dissolves in water. | High solubility suggests a potential for aqueous environmental compartments (freshwater, marine). |

| Vapor Pressure | A measure of a chemical's tendency to evaporate. | High vapor pressure indicates a potential for the chemical to partition into the atmospheric compartment. |

| Log Kow | The ratio of a chemical's solubility in octanol to its solubility in water. | A high Log Kow suggests a potential for bioaccumulation and partitioning into organic matter/lipids and sediments. |

| pKa | The pH at which half of the molecules of a weak acid or base are dissociated. | Determines the speciation (charged vs. uncharged) of the molecule, which influences solubility, sorption, and toxicity across different pH levels. |

Q: My experimental data shows high variability in measured exposure concentrations. What could be the cause?

Inconsistent exposure confirmation is a common issue that undermines data reliability. Follow this troubleshooting guide [16]:

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in measured concentrations | - Instability of the test substance in the test system.- Inhomogeneous dosing solutions.- Loss of chemical due to sorption to test vessel walls. | - Validate chemical stability under test conditions.- Use appropriate solvents and mixing procedures.- Use test vessels made of low-sorption materials (e.g., glass, specific plastics). |

| Measured concentration significantly lower than nominal | - Chemical degradation (hydrolysis, photolysis).- Volatilization.- Microbial degradation. | - Report both nominal and measured concentrations. [16]- Characterize degradation kinetics.- Use closed or flow-through systems as appropriate. |

| Lack of measured exposure data | - No analytical verification performed. | This is a critical failure. Always include analytical confirmation of exposure concentrations; data without it may be deemed unreliable for regulatory purposes or meta-analyses. [16] |

Statistical Analysis and Flowchart Design

Q: How can I ensure my statistical analysis flowchart is accessible to all colleagues, including those using assistive technologies?

Creating accessible diagrams is a key best practice. Relying solely on a visual chart can exclude users. Here is the recommended protocol [17]:

- Provide a Text-Based Alternative: The most robust solution is to provide a text version of the flowchart's logic. This can be done using nested lists or headings that represent the structure [17].

- List Example:

- Heading Example: Use heading levels (H1, H2, H3) to represent the hierarchy of decisions in your chart [17].

- Create a Single Accessible Image: If a visual chart is also needed, export the entire flowchart as a single, high-resolution image. For this image, provide concise alt-text that describes the overall purpose and structure, such as: "Flowchart for identifying relevant environmental compartments based on physicochemical properties. Text details found in the accompanying guide." [17]

- Apply Strict Color Contrast Rules: Ensure sufficient contrast between all foreground elements (text, arrows, symbols) and their background colors. For standard text, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) require a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 [15].

Q: What are the common design pitfalls that make flowcharts difficult to follow?

Avoid these common issues to improve clarity [18]:

- Disorganized Flow: Placing shapes too close together or using long, winding connectors. Maintain consistent spacing and a logical left-to-right or top-to-bottom flow [18].

- Poor Color Contrast: Using color schemes where text or shapes do not distinctly stand out from the background, forcing readers to strain their eyes [18].

- Overcomplication: Including too much detail in one diagram. If a flowchart is too complex, break it into multiple, simpler, linked diagrams [17] [18].

- Undefined Decision Paths: Forks in the logic that are not clearly labeled. Always ensure decision points and the conditions for each path are explicitly defined [18].

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Review and Data Curation Pipeline

This protocol, based on established systematic review practices, outlines the methodology for identifying, curating, and integrating ecotoxicity data to support the identification of relevant environmental compartments [1].

1. Problem Formulation & Literature Search

- Objective: To gather existing ecotoxicity data for a target chemical and use its physicochemical properties to guide the assessment of relevant environmental compartments.

- Search Strategy: Develop a comprehensive search string using online scientific databases (e.g., Web of Science, Scopus). The search should include the chemical name, synonyms, and common acronyms, combined with keywords like "ecotoxicology," "toxicity," and "environmental fate." [1]

- Documentation: Record the exact search strings, databases used, and date of search for full transparency.

2. Study Screening & Selection

- Process: Screen identified references in two phases [1]:

- Title/Abstract Screen: Assess relevance based on pre-defined criteria (e.g., presence of original toxicity data, relevant ecological species).

- Full-Text Review: Apply strict eligibility criteria for acceptability. Key criteria include [1] [16]:

- Analytical verification of exposure concentrations.

- Use of appropriate controls with documented performance.

- Reporting of raw data or effect concentrations in a usable form.

- Flowchart: The study selection process is documented using a PRISMA-style flowchart, as shown in Diagram 1 [1].

3. Data Extraction & Curation

- Data Fields: Extract relevant data into a standardized template. Essential fields include [1] [16]:

- Chemical Information: Name, CASRN, measured physicochemical properties.

- Test Organism: Species, life stage, source.

- Experimental Conditions: Test type (static, flow-through), duration, temperature, pH, endpoints measured.

- Results: Raw data, calculated endpoints (LC50, NOEC), and statistical methods.

- Quality Assurance: All extracted data should be subject to peer review and verification before being added to the final dataset [1].

Visualizing the Systematic Review Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the experimental protocol for literature review and data curation, which forms the basis for identifying relevant environmental compartments.

Decision Framework for Environmental Compartments

This diagram outlines the logical decision process for prioritizing environmental compartments based on a chemical's key physicochemical properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Ecotoxicology Research |

|---|---|

| Reference Toxicants | Standard chemicals (e.g., potassium dichromate, sodium chloride) used to assess the health and sensitivity of test organisms, ensuring the reliability of bioassay results. [16] |

| Analytical Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents used for dissolving test substances, extracting analytes from environmental matrices, and preparing standards for chemical verification. [16] |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Standards with certified chemical concentrations and properties. Used to calibrate instruments and validate analytical methods for quantifying chemical exposure. [16] |

| In-Situ Passive Samplers | Devices deployed in the environment (e.g., SPMD, POCIS) to measure the time-weighted average concentration of bioavailable contaminants in water, sediment, or air. |

| Standardized Test Organisms | Cultured organisms (e.g., Daphnia magna, Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata) with known sensitivity and control performance, providing reproducible and comparable toxicity data. [1] |

| Naphthablin | Naphthablin |

| Dasotraline | Dasotraline, CAS:675126-05-3, MF:C16H15Cl2N, MW:292.2 g/mol |

The Statistical Toolbox: Implementing Hypothesis Tests, Regression Models, and ECx Calculation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental limitations of NOEC/LOEC that justify this paradigm shift?

The No Observed Effect Concentration (NOEC) and Lowest Observed Effect Concentration (LOEC) have several critical limitations [10]:

- Dependence on Test Design: The NOEC depends on the arbitrary choice of test concentrations and the number of replications. A poorly designed experiment with high variability can misleadingly result in a high NOEC [19] [10].

- False Impression of a "No-Effect" Level: The name is potentially misleading; it is not a true "no effect" concentration but merely the highest concentration tested that did not show a statistically significant effect in that specific test [10].

- No Information on Effect Magnitude or Uncertainty: NOEC/LOEC provide no estimate of the variability or uncertainty around the result and cannot describe the concentration-response relationship, making them an inefficient use of data and test organisms [10].

Q2: How do regression-based ECx values address these limitations?

Regression-based procedures model the entire concentration-response relationship [10]. The Effective Concentration (ECx), which is the concentration that causes an x% effect (e.g., EC10, EC50), offers significant advantages [19]:

- Quantifies Effect and Uncertainty: Allows for the calculation of confidence intervals, providing an estimate of the reliability of the result [10].

- Makes Full Use of Data: Uses all data points from the experiment to model the biological response, leading to more robust and informative conclusions [19] [10].

- Enables Extrapolation: The model can estimate effect concentrations that were not directly tested, which is particularly useful when the LOEC is the lowest tested concentration and the NOEC is therefore undefined [10].

Q3: What are the practical challenges when implementing regression-based methods, and how can they be overcome?

- Challenge 1: Model Selection and Fit. Choosing an inappropriate regression model can lead to inaccurate ECx estimates.

- Solution: Use statistical software that supports multiple models (e.g., logistic, probit). Evaluate model fit using goodness-of-fit criteria (e.g., R², AIC) and residual analysis. Ensure your experimental design includes a sufficient number of concentration levels to adequately define the response curve [19].

- Challenge 2: Experimental Effort and Cost. Generating data suitable for regression analysis may require more experimental effort, such as testing more concentrations.

- Solution: The increased initial effort is justified by the more robust and informative output. Furthermore, machine learning approaches are now being developed to predict dose-effect curves, which can significantly reduce the experimental workload in the future [20].

- Challenge 3: Dealing with Intraspecific Variation. Traditional tests often use a single genotype, which may not represent the response of a natural, genetically diverse population [21].

- Solution: Incorporate multiple genotypes or strains into toxicity testing where feasible. Research shows that using a single genotype can fail to produce an estimate within the 95% confidence interval of the population response over half of the time, highlighting the importance of accounting for genetic diversity for accurate risk assessment [21].

Q4: How can novel methods like machine learning (ML) enhance dose-response analysis?

ML models can predict dose-effect relationships while accounting for complex interactions between multiple pollutants. For instance [22]:

- FLIT-SHAP: An explainable ML approach that can extract dose-response relationships (overall, main, and interaction effects) for individual pollutants within a complex mixture, revealing synergistic or antagonistic effects that traditional models miss.

- Reduced Experimental Workload: ML models, such as Gradient-Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT), have been shown to accurately predict toxicity curves for municipal wastewater, potentially reducing the required experimental workload by at least 75% [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Fit in Regression Analysis

Problem: The regression model does not adequately fit your concentration-response data, leading to unreliable ECx estimates.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Visualize Data: Plot the observed data points and the fitted curve. Look for systematic deviations (e.g., S-shaped data fit with a linear model).

- Check Model Assumptions: Ensure your data meets the assumptions of the chosen model (e.g., normality, homoscedasticity of residuals).

- Try Alternative Models: Test different non-linear models (e.g., log-logistic, Gompertz, Weibull) to find the best fit for your data's distribution.

- Review Experimental Design: If poor fit persists, the issue may be with the data. Ensure you have an adequate range of concentrations that capture both the lower and upper asymptotes of the response curve [19].

Issue 2: Handling Non-Additive (Synergistic/Antagonistic) Effects in Chemical Mixtures

Problem: Traditional models like Concentration Addition (CA) and Independent Action (IA) assume additivity, but real-world pollutant mixtures often interact.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Identify the Need: Suspect interactions when the observed mixture toxicity consistently deviates from predictions based on individual component toxicities.

- Employ Advanced Techniques:

- Statistical Methods: Use methods like Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) or weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression to handle multi-pollutant exposures [22].

- Machine Learning: Apply ML models like XGBoost combined with explanation frameworks (e.g., FLIT-SHAP) to elucidate individual pollutant effects and their interactions within a mixture, providing dose-response patterns even with interacting components [22].

Issue 3: High Uncertainty in Low-Effect Zone (e.g., EC10) Estimates

Problem: The confidence intervals for low-effect concentrations like EC10 are very wide, making the estimate unreliable.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Increase Replication: More replicates at concentrations around the anticipated low-effect zone will reduce variability and tighten confidence intervals [19].

- Optimize Concentration Spacing: Ensure you have several test concentrations in the low-effect range to better define this part of the curve.

- Use More Sensitive Endpoints: If possible, select biological endpoints that show a clear graded response at low concentrations.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining a Regression-Based EC50 for Acute Toxicity

Objective: To determine the concentration that causes a 50% effect in a population over a short-term exposure.

Materials:

- Test organisms (e.g., Daphnia magna)

- Test chemical in known concentrations

- Control dilution water

- Exposure chambers

- Environmental control system (temperature, light)

Procedure:

- Design: Select at least five concentrations and a control, spaced logarithmically to cover a range from 0% to 100% effect.

- Exposure: Randomly assign organisms to each treatment and control group. Use a minimum of four replicates per concentration.

- Randomization: Randomize the position of exposure chambers in the test system to avoid positional bias.

- Observation: Record the response (e.g., mortality, immobilization) at specified time intervals (e.g., 24h and 48h).

- Data Analysis: Fit a non-linear regression model (e.g., a log-logistic model) to the data. Use statistical software to calculate the EC50 and its 95% confidence interval from the fitted curve.

Protocol 2: Applying FLIT-SHAP for Mixture Toxicity Analysis

Objective: To model the dose-response relationship of individual pollutants in a mixture, accounting for interactions [22].

Materials:

- Laboratory equipment for oxidative potential (OP) measurement (e.g., dithiothreitol (DTT) assay)

- Redox-active species (e.g., PQN, 1,2-NQ, Cu(II), Mn(II))

- Computational resources with Python/R and XGBoost, SHAP libraries

Procedure:

- Data Generation: Conduct laboratory-simulated measurements of OP using a mixture of multiple redox-active species. The concentration range for each species should be based on environmental relevance, including a zero concentration [22].

- Model Training: Train a robust machine learning model, such as eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), on the generated concentration and OP data [22].

- Interpretation with FLIT-SHAP: Apply the FLIT-SHAP method to the trained model. This method localizes the intercept of the standard SHAP model to:

- Extract the overall, main, and total-interaction (synergistic/antagonistic) dose-response relationships for each pollutant.

- Visualize how interactions between species alter the OP at different concentration levels [22].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of NOEC/LOEC and Regression-Based ECx Approaches

| Feature | NOEC/LOEC (ANOVA-type) | Regression-Based ECx |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Basis | Hypothesis testing (e.g., Dunnett's test) | Non-linear regression modeling |

| Output | Two discrete concentrations (NOEC, LOEC) | A continuous ECx value with confidence intervals |

| Dependence on Test Design | High; arbitrary concentration spacing affects result [10] | Lower; interpolates within tested range |

| Information on Curve Shape | No [10] | Yes, models the entire relationship [10] |

| Quantification of Uncertainty | No [10] | Yes, via confidence intervals [10] |

| Data Efficiency | Low; uses only significance testing between groups [10] | High; uses all data points to fit a model [10] |

| Recommended Use | Phasing out as a main summary parameter [19] [10] | Preferred method for modern risk assessment [19] [10] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Ecotoxicology

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | A probe to measure the oxidative potential (OP) of particulate matter by simulating lung antioxidant responses. | Quantifying the toxicity of PM components and their mixtures [22]. |

| Phenanthrenequinone (PQN) | A redox-active quinone used as a standard challenge in OP assays. | Studying the contribution of organic species to the OP of PM in laboratory-controlled mixtures [22]. |

| Daphnia magna | A model freshwater crustacean used in standard ecotoxicity testing. | Determining acute (immobilization) and chronic (reproduction) toxicity endpoints for chemicals [21]. |

| Zebrafish Embryos | A vertebrate model for developmental toxicity and high-throughput screening. | Predicting the dose-effect curve of municipal wastewater toxicity using machine learning [20]. |

| Microcystis spp. | A genus of cyanobacteria that produce microcystin toxins. | Studying the effects of harmful algal blooms (HABs) and intraspecific variation in toxin tolerance [21]. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Decision Flowchart for Ecotoxicity Data Analysis

Diagram 2: Workflow for Machine Learning-Based Mixture Toxicity Analysis

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) for researchers in ecotoxicology and related fields navigating three specific statistical tests. Proper application of Dunnett's, Williams', and Jonckheere-Terpstra tests is crucial for analyzing data from toxicity studies, dose-response experiments, and other research involving multiple comparisons or ordered alternatives. The following sections offer detailed protocols and solutions to common problems framed within the context of ecotoxicological research.

Test Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the core purpose and application context for each statistical test to help guide your selection.

| Test Name | Primary Purpose | Ideal Use Case in Ecotoxicology |

|---|---|---|

| Dunnett's Test [23] | Multiple comparisons to a single control group [23]. | Comparing several pesticide treatment groups to an untreated control to identify which concentrations cause a significant effect [23]. |

| Williams' Test | To test for a monotonic trend (increasing or decreasing) across ordered treatment groups. | Analyzing a dose-response relationship where you expect a consistent increase (or decrease) in mortality with increasing contaminant concentration. |

| Jonckheere-Terpstra Test [24] [25] | To determine if there is a statistically significant ordered trend between an ordinal independent variable and a dependent variable [24] [25]. | Assessing whether reproductive success in birds decreases with increasing levels of environmental pollutant exposure (e.g., "Low," "Medium," "High") [24]. |

Figure 1: Statistical Test Selection Flowchart for Ecotoxicology Experiments

Dunnett's Test

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Test statistic not displayed in output. | Software may not display it by default [26]. | In software like JMP, the test statistic (Q, similar to a t-statistic) can often be found in detailed output tables, such as the "LSMeans Differences Dunnett" table [26]. |

| Unequal group sizes. | Original Dunnett's table assumes equal group sizes [27]. | Most modern statistical software can handle unequal sample sizes computationally. Verify that your software uses the corrected calculation [27]. |

| Interpretation of result is unclear. | - | A significant result (p < 0.05) for a treatment indicates its mean is significantly different from the control mean. The sign of the difference (positive/negative) indicates the direction of the effect [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the test statistic for Dunnett's procedure, and how do I report it? The test statistic for Dunnett's test is often denoted as Q in software outputs, which is equivalent to a t-statistic for multiple comparisons to a control [26]. When reporting results for a publication, you should include the Q statistic, its associated degrees of freedom, and the p-value for each significant comparison [26].

Q2: My experiment has one control and three treatment groups. How many comparisons does Dunnett's test make? Dunnett's test makes (k-1) comparisons, where k is the total number of groups (including the control) [23]. In your case, with 4 total groups, it performs 3 comparisons. This makes it more powerful than tests like Tukey's that would perform all possible pairwise comparisons[k(k-1)/2 = 6 comparisons] [23].

Jonckheere-Terpstra Test

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| A significant J-T result, but medians are not perfectly ordered. | The J-T test is a test of stochastic ordering, not just medians. It can be significant even if medians are equal, as long as the overall distributions show a trend [28]. | This is not necessarily an error. Interpret the result as a general trend in the data distributions across the ordered groups. |

| Negative test statistic. | The predicted order of the alternative hypothesis is the reverse of the actual data trend [28]. | A negative J-T statistic with a significant p-value supports an alternative hypothesis that the values are decreasing as the group order increases [28]. |

| Test is not significant, but some group differences are. | The J-T test evaluates a single, consistent trend across all groups. A reversal in trend between two groups can reduce the overall statistic [28]. | The test may lack power if the true pattern is not monotonically increasing or decreasing. Consider if your hypothesis is truly about a directional trend. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the key difference between the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Jonckheere-Terpstra test? Both are non-parametric, but they test different hypotheses. The Kruskal-Wallis test is a general test that determines if there are any significant differences among the medians of three or more independent groups, without specifying the nature of those differences [24] [25]. The Jonckheere-Terpstra test is more specific and powerful when you have an a priori ordered alternative hypothesis; it tests specifically for an increasing or decreasing trend across the groups [24] [25].

Q2: What are the critical assumptions I must check before running the Jonckheere-Terpstra test? The main assumptions are [24] [25]:

- Ordinal or Continuous Data: The dependent variable should be measured on an ordinal, interval, or ratio scale.

- Ordinal Independent Variable: The independent variable should consist of two or more categorical, independent groups with a logical order (e.g., "Low," "Medium," "High").

- Independence of Observations: There must be no relationship between the observations in different groups.

- A Priori Order and Direction: You must specify the order of the groups and the predicted direction of the trend (increasing or decreasing) before looking at the data [24].

Williams' Test

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Test fails to detect a known trend. | The test assumes a specific monotonic dose-response shape. The data may have a non-monotonic (e.g., umbrella) shape. | Visually inspect the data. If the trend reverses, the standard Williams test is not appropriate. Consider the Mack-Wolfe test for umbrella alternatives. |

| Assumption of normality and equal variance violated. | Biological data, such as count or percentage data from ecotoxicology studies, often violate these parametric assumptions [29]. | Check if your software offers a non-parametric version of the Williams test. Alternatively, data transformation might be necessary before analysis. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use Williams' test over the Jonckheere-Terpstra test? Use Williams' test when you are working with continuous data that meets parametric assumptions (like normality) and you have a specific reason to believe the trend follows a monotonic pattern (consistently increasing or decreasing), often modeled by a regression function. Use the Jonckheere-Terpstra test as a non-parametric alternative when your data are ordinal or do not meet parametric assumptions, as it tests for a trend based on the ranks of the data.

Q2: My Williams' test is significant. What is the main conclusion? A significant Williams' test allows you to conclude that there is a statistically significant monotonic trend across the ordered treatment groups. This means that as you move from one ordered group to the next (e.g., from low dose to high dose), the response variable consistently increases (or decreases, depending on your hypothesis) in a way that is unlikely to be due to random chance alone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials and solutions commonly used in ecotoxicology experiments that generate data for the statistical tests discussed above.

| Item | Function in Ecotoxicology Research |

|---|---|

| Test Chemical/Compound | The substance whose toxic effects are being investigated. Its source, purity, and chemical properties must be well-characterized and reported [16]. |

| Vehicle/Solvent Control | A negative control group exposed to the solvent (e.g., water, acetone, DMSO) used to deliver the test chemical, but without the test chemical itself. This is the baseline for comparison in tests like Dunnett's [16]. |

| Analytical Grade Reagents | High-purity chemicals used to confirm the exposure concentrations in test vessels via chemical analysis. This is critical for verifying the dose-response relationship [16]. |

| Defined Animal Feed | A consistent, contaminant-free diet for test organisms to ensure that observed effects are due to the test chemical and not nutritional variability or contaminants in food [29]. |

| Reference Toxicant | A standard chemical (e.g., potassium dichromate, copper sulfate) with known and reproducible toxicity used to validate the health and sensitivity of the test organisms over time [29]. |

| Carpetimycin A | Carpetimycin A, CAS:76025-73-5, MF:C14H18N2O6S, MW:342.37 g/mol |

| Teglicar | Teglicar, CAS:250694-07-6, MF:C22H45N3O3, MW:399.6 g/mol |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Robust Statistical Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between Log-Logistic, Probit, and Weibull models for dose-response analysis?

These models are nonlinear regression models used to describe the relationship between dose and effect, but they differ in their underlying assumptions and shape characteristics [30]. The Log-logistic model (including its parameterized forms like LL.4 in R) is symmetric about its inflection point [30]. The Probit model is similar to the Logit model but is based on the cumulative Gaussian distribution [30]. The Weibull model is asymmetric and provides more flexibility for curves where the effect changes at a different rate on either side of the inflection point [30] [31].

Q2: I received a 'singular gradient' error when fitting a model with nls in R. How can I resolve this?

This common error often arises from an issue with the initial parameter values provided to the algorithm [32]. Solutions include:

- Use the

drcpackage: It provides robust self-starting functions (e.g.,LL.4,W1.4) that automatically calculate sensible initial values, often resolving the issue [32]. - Refine initial estimates: If using

nls, ensure your starting values are as close as possible to the true parameter values. Plotting the data and manually estimating the upper, lower asymptotes, and EC50 can help. - Check the scale: If your concentration values span several orders of magnitude, use log-transformed concentrations in your model. The

drcpackage functions likeLL2.4are designed for this and handle the log-transformation within the model [32].

Q3: My dose-response data shows stimulatory effects at low doses (hormesis) before inhibition at higher doses. Can these models handle that? Standard 4-parameter models (Log-logistic, Weibull) are designed for monotonic curves and typically cannot describe non-monotonic, hormetic data [30] [33]. For such data, specialized models are required. The Brain-Cousens model and the Cedergreen–Ritz–Streibig model are extensions of the log-logistic model specifically designed to account for hormesis [30]. Recent research also proposes more universal dynamic models, like the Delayed Ricker Difference Model (DRDM), which can fit various curve types, including those with hormesis [30].

Q4: How do I choose the best model for my dataset? The best practice is to fit several models and use statistical criteria to compare their goodness-of-fit [31] [33].

- Visually inspect the fitted curves overlaid on the raw data.

- Use information criteria like the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) or Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). A lower BIC value generally indicates a better model, as it rewards goodness-of-fit while penalizing model complexity to avoid overfitting [33].

- Check the residual plots for patterns that might suggest a poor fit.

Q5: How can I calculate and plot mortality percentages as the response variable? To use mortality (or survival) percentages, you must first aggregate your raw data. If your raw data has a binary status column (e.g., 1=survived, 0=died), you can calculate the survival percentage for each concentration and replicate group [34]. These calculated percentages then become the response variable for the model.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Model Fitting Fails or Yields Unreasonable Parameter Estimates

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

"Singular gradient" error (in nls). |

Poor initial parameter values [32]. | Use the drc package or manually refine starting values. |

| EC50 estimate is far outside the tested concentration range. | Model lacks sufficient data points near the true EC50. | Ensure your experimental design includes concentrations bracketing the expected effective range. |

| Upper or lower asymptote estimates are unrealistic. | The measured effect does not reach a clear plateau at the highest/lowest doses. | Test more extreme concentrations or constrain the parameters if biologically justified. |

Problem 2: Confidence Intervals for the Curve Are Missing or Look Incorrect

- Cause: The prediction was made without requesting an interval, or the model fit is too uncertain.

- Solution: When generating predictions for plotting, explicitly request the confidence interval. The

drcpackage'spredictfunction and thedrmfunction handle this seamlessly [34] [35].

Problem 3: Handling Multiphasic Dose-Response Curves

- Cause: The biological system exhibits more than one point of inflection, suggesting multiple underlying mechanisms of action [33].

- Solution: The standard 4-parameter models will fail. Use a model designed for multiphasic curves. One approach is to use a general model that combines multiple independent Hill-type processes [33]: ( E(C) = \prod{i=1}^{n} Ei(C) ) where ( E_i(C) ) is the effect of the i-th independent process described by a Hill-type equation. Specialized software like Dr. Fit has automated algorithms to generate and rank models with varying degrees of multiphasic features [33].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standard Protocol for Dose-Response Curve Fitting in R

- Data Preparation: Load your data with columns for dose/concentration and the response. Ensure the response is in the correct units (e.g., percentage, raw signal, cell count) [31] [35].

- Initial Visualization: Plot the raw data using a scatter plot to understand the underlying trend (e.g., monotonic decrease, sigmoidal shape, hormesis) [31].

- Model Fitting: Use the

drcpackage to fit multiple models. - Model Selection: Compare models using the

AICorBICfunction. Visually inspect the fits using theplotfunction. - Parameter Extraction: Use the

summary()function on the best model to obtain parameters (EC50, hill slope, asymptotes) and their standard errors. - Visualization with Confidence Band: Generate a smooth prediction with confidence intervals and plot it alongside the raw data, as shown in the troubleshooting guide above.

Summary of Key Model Parameterizations

The following table summarizes the common four-parameter model used in the drc package, which can be adapted to represent Log-logistic, Weibull, and other forms.

Table 1: Key Parameterizations of the Four-Parameter Dose-Response Model in drc.

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Biological/Toxicological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Limit | d | The response value at dose zero (control). | The baseline level of the measured effect in the absence of the stressor. |

| Lower Limit | c | The response value at infinitely high doses. | The maximum possible effect (e.g., minimum cell viability, maximum inhibition). |

| Hill Slope | b | The steepness of the curve at the inflection point. | Reflects the cooperativity of the effect; a steeper slope suggests a more abrupt transition. |

| EC50 / IC50 | e | The dose that produces the effect halfway between the upper and lower limits. | The potency of the chemical. For inhibition, this is often called IC50. |

The core model structure is [35]: ( f(x) = c + \frac{d-c}{1+(\frac{x}{e})^b} ) Where ( x ) is the dose, ( f(x) ) is the predicted response, and ( b, c, d, e ) are the parameters described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Function in Dose-Response Analysis |

|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | A free software environment for statistical computing and graphics, essential for complex curve fitting [31] [32]. |

drc R Package |

A core package specifically for the analysis of dose-response data. It provides a suite of functions for fitting, comparing, and visualizing a wide array of models [31] [34] [32]. |

bmd R Package |

Used to calculate Benchmark Doses (BMD) and their lower confidence limits (BMDL), which are critical values for chemical risk assessment [31]. |

| Dr. Fit Software | A freely available tool designed for automated fitting of dose-response curves, including those with multiphasic (hormetic) features [33]. |

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | A curated database of single chemical ecotoxicity data, used to obtain high-quality experimental data for modeling and validation [1]. |

| Seitomycin | Seitomycin, MF:C20H18O6, MW:354.4 g/mol |

| Cindunistat | Cindunistat, CAS:364067-22-1, MF:C8H17N3O2S, MW:219.31 g/mol |

Workflow and Model Relationships Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for dose-response analysis within an ecotoxicology framework, from data collection to model selection and interpretation.

Dose-Response Analysis Workflow in Ecotoxicology

The diagram below shows the relationship between different models and the types of data they are designed to fit, highlighting the path from simple to complex models.

Model Selection Based on Data Characteristics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between an ECx and a Benchmark Dose (BMD)?

While both are point-of-departure metrics derived from dose-response data, they are defined differently. An ECx (e.g., EC10, EC50) is the Effective Concentration that causes an x% change in the response relative to the maximum possible effect [36]. In contrast, the Benchmark Dose (BMD) is the dose that produces a predetermined change in the response rate of an adverse effect, known as the Benchmark Response (BMR) [37]. The key difference is that the BMD is model-derived and accounts for the entire dataset and variability, making it less dependent on the specific doses tested in the experiment compared to the traditional NOAEL/LOAEL approach [37].

Q2: My dataset has only one dose group showing a response above the control. Is it suitable for BMD modeling?

Generally, no. Datasets in which a response is only observed at a single, high dose are usually not suitable for reliable BMD modeling [37]. A minimum of three dosing groups plus one control group is typically required to establish a clear dose-response trend, which is essential for fitting mathematical models [37].

Q3: How do I choose a Benchmark Response (BMR) value for my analysis?

The BMR is not universally fixed and should ideally be based on biological or toxicological knowledge of the test system [38]. However, regulatory bodies provide default values. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) often uses a 5% BMR for continuous data and a 10% excess risk for quantal (binary) data [37]. The US EPA frequently recommends a 10% BMR for both data types [37]. The BMR should be chosen in the lower end of the observable dose range of your specific dataset [38].

Q4: Multiple models in the BMDS software fit my data adequately. How do I select the best one?

Current EPA guidance recommends a decision process. First, check if the BMDLs from all adequately fitting models are "sufficiently close" (generally within a 3-fold range). If they are not, you should select the model with the lowest BMDL for a conservative estimate. If the BMDLs are sufficiently close, you should select the model with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). If multiple models have the same AIC, it is recommended to combine the BMDLs from those models [37].

Q5: Why is the BMDL, rather than the BMD, used to derive health guidance values?

The BMDL is the lower confidence limit of the BMD. It is a more conservative and statistically robust point of departure because it accounts for uncertainty in the BMD estimate [37] [38]. Using the BMDL helps ensure that the derived health guidance values, such as the Reference Dose (RfD) or Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI), are protective of human health by incorporating the statistical uncertainty of the experimental data [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inadequate Model Fit or Failure to Calculate BMDL

- Symptoms: The software fails to converge, provides an error, or the fitted model visually poorly represents the data points.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Data Spread: The response may be only at background levels or already at maximum at all tested doses. Ensure your study includes doses that elicit a range of responses between the background and maximum effect [39].

- Poor Data Quality or High Variability: High variability within dose groups can prevent a good model fit. Review your experimental protocol to identify and control for sources of variability.

- Incorrect Data Type Specification: Ensure you have correctly specified your data as quantal (dichotomous) or continuous in the software, as this determines the available models and calculations [37].

- Model Misspecification: The chosen model family (e.g., log-normal, Weibull) may be inappropriate for your data's dose-response shape. Try other available models or consider using model averaging techniques, which are now available in some software like the

bmdR package [38].

Problem 2: Large Confidence Intervals on ECx or BMD Estimates

- Symptoms: The confidence interval for your calculated metric is very wide, indicating high uncertainty.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Small Sample Size: This is a common cause. Increasing the number of replicates per dose group can reduce variability and tighten confidence intervals.

- Poor Dose Spacing: If doses are too far apart, the model has less information to define the curve's shape precisely. Designs with more dose groups and spacing that captures the rising part of the curve are preferable [37] [39].

- High Intra-group Variability: Identify and minimize technical and biological sources of noise in your assay.

Problem 3: Discrepancies Between NOAEL and BMDL Values

- Symptoms: The calculated BMDL is significantly higher or lower than the study's determined NOAEL.

- Interpretation and Solutions: This is expected and highlights a key advantage of the BMD approach. The BMDL is less dependent on arbitrary dose selection and sample size than the NOAEL [37].

- If BMDL > NOAEL: This often occurs when the sample size is large, giving a more powerful and precise estimate [37].

- If BMDL < NOAEL: This can happen with small sample sizes, where the NOAEL may be overstated due to low statistical power. The BMDL provides a more conservative and statistically justified estimate in such cases [37]. Rely on the BMDL as it uses all the dose-response information.

Quantitative Data and Metric Definitions

Table 1: Summary of Key Dose-Response Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| EC50 | The concentration that produces 50% of the maximum possible response [36]. | Measures a compound's potency; commonly used in pharmacology and toxicology. |

| EC10 | The concentration that produces a 10% change in response relative to the maximum possible effect. | Used as a point of departure for risk assessment, estimating a low-effect level. |

| BMD | The dose that produces a predetermined change in the response rate (the BMR) [37]. | A model-derived point of departure for risk assessment that uses all experimental data. |

| BMDL | The lower confidence limit (usually 95%) of the BMD [37] [38]. | A conservative value used to derive health guidance values (e.g., RfD, ADI). |

Table 2: Default Benchmark Response (BMR) Values by Data Type and Authority

| Response Data Type | Examples | Default BMR |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Body weight, cell proliferation, blood cell count [37] | 5% (EFSA) [37] / 10% (EPA) [37] |

| Quantal (Dichotomous) | Tumor incidence, mortality rate [37] | 10% (Excess Risk) [37] [38] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow

Protocol 1: Benchmark Dose Analysis using Regulatory Software

This protocol outlines the steps for performing a BMD analysis using software like the US EPA's BMDS.

- Data Evaluation: Confirm your dataset is suitable. It must show a clear dose-response trend with a minimum of three dose groups and one control group [37]. The data should be reported as either quantal (e.g., 5/50 affected) or continuous (mean ± SD) [39].

- Define BMR: Select an appropriate Benchmark Response (BMR) based on your data type and relevant regulatory guidance (see Table 2).

- Model Fitting: Run several mathematical models (e.g., Log-Logistic, Weibull, Gamma) available in the software against your dose-response data.

- Model Evaluation: Inspect the goodness-of-fit for each model (e.g., p-value > 0.1 indicates an adequate fit). Visually assess how well the model curve fits the data points [37].

- Model Selection: If multiple models fit adequately, apply the model selection criteria (e.g., lowest AIC, sufficiently close BMDLs) to choose a single best model or use model averaging [37] [38].

- Record BMDL: The primary output for risk assessment is the BMDL from the selected model.

Protocol 2: Calculating EC50 from Concentration-Response Data

For a simple, non-computational estimation of the EC50 when data is limited or for verification:

- Plot the Data: Graph the concentration (x-axis, typically log-scale) against the response (y-axis, % of maximum effect).

- Identify 50% Response: Draw a horizontal line from the 50% mark on the y-axis to the point where it intersects the fitted curve or the linear portion of your data.

- Interpolate EC50: From the intersection point, draw a vertical line down to the x-axis. The concentration value at this point is the estimated EC50 [36]. For more accuracy, a mathematical interpolation method using the data points immediately above and below the 50% response level can be employed [36].

Visual Workflows

BMD Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Software and Reagents for Dose-Response Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| US EPA BMDS | A standalone software package providing a suite of models for BMD analysis. | The preferred tool for regulatory submissions to agencies like the US EPA [37]. |

R Package bmd |

An extension package for the R environment that uses the drc package for dose-response analysis. |

Offers high flexibility, modern statistical methods (e.g., model averaging), and integration with other R analyses [38]. |

| PROAST | Software from the Dutch National Institute for Public Health (RIVM). | An internationally recognized tool for BMD estimation, particularly in Europe [37]. |

| Positive Control Compound | A chemical with a known and reproducible dose-response effect. | Used to validate the experimental assay system and ensure it is responding as expected. |