Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA): A Foundational Guide for Sustainable Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA), a critical systematic process for evaluating the environmental impact of human activities, with a focused lens on pharmaceutical development.

Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA): A Foundational Guide for Sustainable Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA), a critical systematic process for evaluating the environmental impact of human activities, with a focused lens on pharmaceutical development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of ERA, including the One Health framework and regulatory drivers. The scope extends to detailed methodological approaches, from tiered testing strategies to advanced modeling, and addresses current challenges such as data gaps and the integration of non-animal testing methodologies. Finally, it examines emerging trends, including Next-Generation ERA and the use of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), offering insights for embedding robust environmental stewardship into the drug development lifecycle.

What is Ecological Risk Assessment? Core Principles and Regulatory Drivers

Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) is a systematic, quantitative framework designed to evaluate the likelihood of adverse environmental impacts resulting from human activities, thereby serving as a critical tool for informed environmental decision-making [1]. It offers a structured process that incorporates specific concepts and methodologies to assess environmental health, aiming to balance ecological protection with economic and social considerations [1]. The strength of ERA lies in its scientific rigor and transparency; it systematically separates the scientific process of risk analysis from the policy-oriented process of risk management [1] [2]. This separation ensures that ecological risks are evaluated objectively before being weighed against the costs and benefits of mitigation actions, providing a defensible foundation for environmental policy and regulation [1].

The core objective of ERA is to produce defensible estimates of the magnitude and probability of adverse effects on ecological entities, or "assessment endpoints," which are explicit expressions of the environmental values to be protected, such as ecosystem function and biodiversity [2]. The process is fundamentally designed to address the question: "What are the consequences of human activities on the environment, and what is the probability that they will occur?" [1]. By providing a structured yet flexible approach, ERA has become an indispensable practice for regulating chemicals, planning industrial developments, and managing ecosystem health, allowing decision-makers to prioritize actions and allocate limited resources effectively to minimize environmental harm [1] [2].

Core Concepts and Terminology in ERA

A clear understanding of key terms is essential for comprehending the ERA framework and its application.

- Environmental Value: This represents significant aspects of an ecosystem, encompassing its ecological, social, and economic importance. It goes beyond monetary worth to include cultural and ecological relevance, such as the value of a clean water supply or high species diversity [1].

- Indicators: These are measurable parameters that reveal patterns or trends in environmental health. Examples include population counts of endangered species or changes in land use. Indicators provide a practical means to assess and monitor ecological conditions [1].

- Pressures: These are human-induced factors that stress ecosystems, leading to cumulative impacts over time. Land use changes, industrial development, and pollution are common examples of pressures [1].

- Risk: In the context of ERA, risk is defined as the likelihood of environmental degradation occurring. It is often measured using indicators and established thresholds, which help identify the potential impact and severity of human actions [1].

- Risk Class: This system categorizes risk levels (e.g., from very low to very high) to help assess the severity of potential ecological damage and guide management efforts by prioritizing areas needing intervention [1].

- Assessment Endpoints: These are formal statements of the actual environmental values that are to be protected, largely determined by societal perception. Examples include the protection of vertebrate species or critical ecosystem services [2].

- Measurement Endpoints: These are the measurable responses (e.g., LC50 from a toxicity test) to a stressor that are used to infer effects on the assessment endpoints. There is often a mismatch between what is easily measured in the lab and the ultimate ecological value to be protected, which is a central challenge in ERA [2].

The Systematic ERA Process

The ERA process is typically broken down into two main phases: Preparation and Assessment, followed by the reporting of results and development of risk management strategies [1]. This process is often tiered, starting with simple, conservative screening assessments and progressing to more complex, refined analyses if initial tiers indicate potential risk [2].

Phase One: Preparation

This initial phase establishes the foundation for the entire assessment.

- Step 1: Establish the Context: This involves defining the scope, goals, and boundaries of the assessment, including a clear statement of the environmental issues to be addressed [1].

- Step 2: Identify and Characterize Key Environmental Pressures: Here, the human-induced factors or activities that may stress the environment are recognized and described [1].

- Step 3: Specify Environmental Values and Indicators: The relevant environmental values for the assessment are chosen, and corresponding indicators are selected to measure environmental health and evaluate risks [1].

Phase Two: Assessment

The assessment phase involves the analytical work of evaluating risks.

- Step 4: Characterize Environmental Trends and Establish Risk Classes: Current and historical trends for the chosen indicators are evaluated. The degree of risk for each indicator is then categorized (e.g., low, moderate, high) [1].

- Step 5: Evaluate Changes to Indicators and Risks: This step involves analyzing how environmental indicators and their associated risks may change under different future scenarios, based on projected human activities and pressures [1].

- Step 6: Report Results and Develop Risk Reduction Strategies: The findings of the ERA are presented in a clear and actionable manner. Subsequently, strategies to mitigate or manage the identified risks are proposed [1].

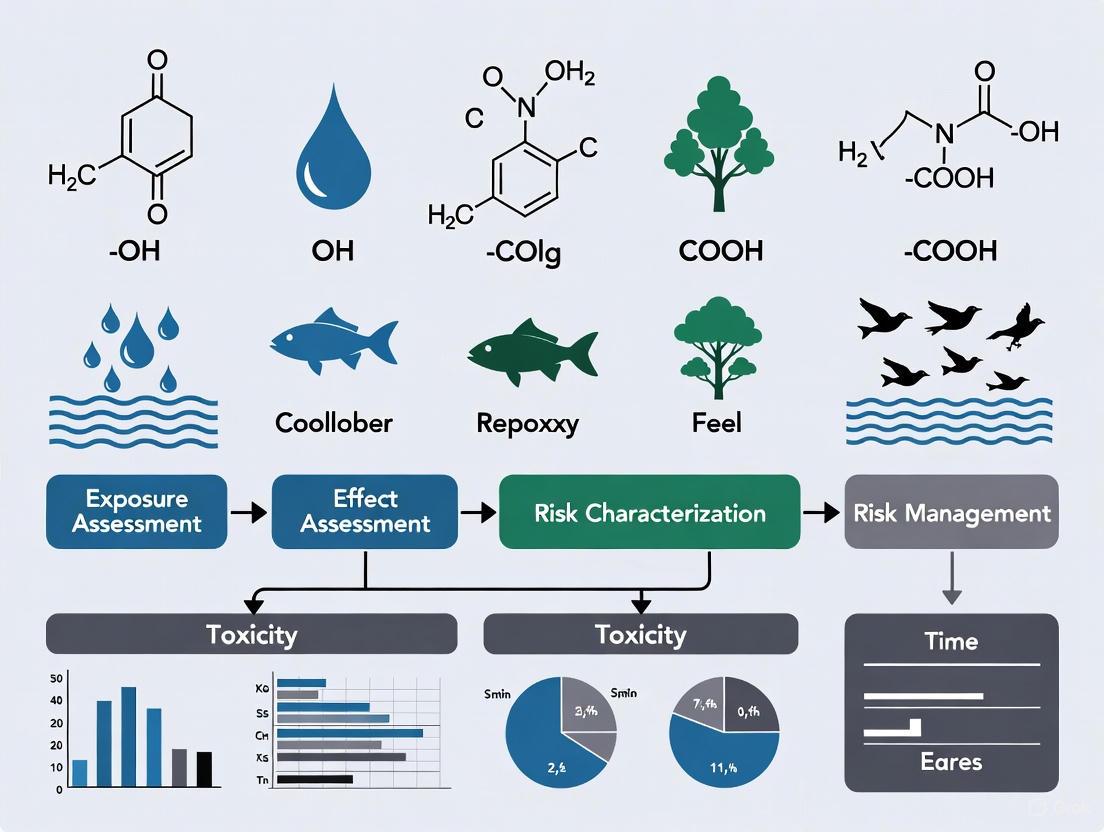

The following workflow diagram visualizes this systematic process, showing the integration of its key components.

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols in ERA

A variety of monitoring techniques and experimental approaches are employed within the ERA framework to gather data on exposure and effects. These methods range from chemical analyses to complex ecosystem-level studies.

Environmental Monitoring Methods

The table below summarizes the primary monitoring techniques used to assess environmental risks.

Table 1: Environmental Monitoring Methods in ERA

| Method | Acronym | Primary Function | Key Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Monitoring | CM | Measures levels of known contaminants in the environment. | Provides direct quantification of pollutant concentrations in water, soil, or air [1]. |

| Bioaccumulation Monitoring | BAM | Examines contaminant levels in organisms and assesses accumulation risks. | Tracks processes like bioconcentration (uptake from water) and biomagnification (increase up the food chain) [1]. |

| Biological Effect Monitoring | BEM | Identifies early biological changes (biomarkers) indicating exposure to contaminants. | Uses suborganismal responses (e.g., enzyme inhibition) as early warning signals of stress [1]. |

| Health Monitoring | HM | Detects irreversible damage or diseases in organisms caused by pollutants. | Focuses on pathological endpoints, such as tissue damage or tumors, indicating significant harm [1]. |

| Ecosystem Monitoring | EM | Evaluates ecosystem health by examining biodiversity, species composition, and population densities. | Provides an integrated measure of ecological impact at the community or ecosystem level [1]. |

Methodologies Across Levels of Biological Organization

ERA can be conducted at different levels of biological organization, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages. The choice of level involves a trade-off between ecological relevance, practicality, and cost.

Table 2: ERA Across Levels of Biological Organization

| Level of Organization | Pros | Cons | Example Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suborganismal (Biomarkers) | High-throughput, cost-effective for screening; establishes clear cause-effect relationships [2]. | Large distance between measurement and ecological protection goals; may not predict higher-level effects [2]. | Fish Bioaccumulation Markers: Measure concentrations of persistent hydrophobic chemicals (e.g., PCBs) in tissues like liver or fat. Enzyme Assays: Quantify inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in fish brain tissue to indicate pesticide exposure [1]. |

| Individual | Standardized, reproducible tests; uses model species (e.g., Daphnia magna); low variability [2]. | Limited ecological relevance; ignores species interactions and recovery processes [2]. | Acute Toxicity Tests (e.g., OECD 202): Expose Daphnia magna to a chemical for 48 hours to determine the LC50 (Lethal Concentration for 50% of the population). Chronic Life-Cycle Tests (e.g., OECD 211): Expose Daphnia over 21 days to assess effects on reproduction and survival [2]. |

| Population | More ecologically relevant; can inform on recovery potential and genetic diversity [2]. | More complex and costly than individual-level tests; requires modeling for extrapolation [2]. | Population Modeling: Use matrix models or individual-based models (IBMs) to project long-term impacts on population growth rate based on individual-level effects data. |

| Community & Ecosystem | High ecological relevance; captures indirect effects and ecosystem services; accounts for species interactions [2]. | High cost and complexity; low reproducibility; difficult to establish causality for specific chemicals [2]. | Mesocosm Studies: Enclosed, semi-natural systems (e.g., pond communities) are exposed to a stressor. Multiple endpoints (species abundance, chlorophyll levels, decomposition rates) are monitored over time to derive a NOEC (No Observed Effect Concentration) for the community [2]. |

The relationships between these methodologies and the biological levels they inform are depicted in the following diagram.

Advanced and Integrated Methodologies

Recent advancements in ERA focus on integrating ecosystem services and employing sophisticated modeling.

- Integration of Ecosystem Services (ES): A novel approach integrates the assessment of ecosystem service supply directly into the ERA framework. This ERA-ES method quantitatively assesses both risks and benefits to ES supply resulting from human activities. In this context, 'risk' is defined as the probability that an activity will degrade ecosystem functions, causing ES supply to fall below a critical threshold, while 'benefit' is the potential for human actions to enhance ecosystem processes [3]. For example, a case study assessing an offshore wind farm used sediment denitrification rates as a key indicator for the waste remediation ecosystem service. The methodology involved measuring changes in sediment characteristics like total organic matter (TOM) and fine sediment fraction (FSF), and using a multiple linear regression model to quantify the impact on denitrification [3].

- Mathematical Modeling for Extrapolation: To bridge data gaps between different levels of biological organization, various mathematical models are used. These include:

- Mechanistic Effect Models: These models simulate ecological processes to predict effects at higher organizational levels (e.g., populations, communities) based on data from lower levels (e.g., individuals) [2].

- Extrapolation Models: Models like Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) are used to estimate safe chemical concentrations for entire ecological communities based on toxicity data from a limited set of laboratory species [2].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, biological models, and tools frequently used in ERA experiments, particularly in regulatory toxicology.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in ERA

| Item | Function in ERA | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Test Species | Model organisms used to generate reproducible toxicity data under controlled laboratory conditions. | Daphnia magna (water flea): Used in acute (48-h) and chronic (21-day) toxicity tests for freshwater invertebrates [2]. |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Kits to measure specific biochemical responses (biomarkers) that indicate exposure or early biological effects. | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Assay Kit: Used to measure AChE inhibition in fish brain tissue as a specific biomarker of organophosphate and carbamate pesticide exposure [1]. |

| Chemical Reference Standards | High-purity analytical standards of contaminants for calibrating equipment and quantifying environmental concentrations. | PCB Congener Mixtures: Used in chemical monitoring (CM) and bioaccumulation monitoring (BAM) to identify and quantify polychlorinated biphenyls in environmental and tissue samples [1]. |

| Sediment & Water Samplers | Field equipment for collecting environmental samples that are representative of the ecosystem being assessed. | Grab Samplers and Corers: Used to collect water and sediment samples from marine or freshwater systems for subsequent chemical and ecological analysis in monitoring programs [3]. |

| Resorantel | Resorantel, CAS:20788-07-2, MF:C13H10BrNO3, MW:308.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Altersolanol A | Altersolanol A, CAS:22268-16-2, MF:C16H16O8, MW:336.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Ecological Risk Assessment is a dynamic and critical discipline that provides a structured, scientific basis for understanding and managing the environmental impacts of human activities. Its systematic process—from problem formulation and exposure characterization to risk estimation and management—ensures that decisions are transparent, defensible, and protective of ecological values. The field continues to evolve, with current research focusing on integrating ecosystem services and developing more sophisticated modeling approaches to bridge the gap between simplified laboratory tests and complex real-world ecosystems [3] [2]. For researchers and risk assessors, a comprehensive understanding of the various methodologies across biological levels, along with their associated tools and protocols, is fundamental to conducting robust ERAs that effectively safeguard environmental health.

The One Health concept represents an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems [4]. This approach recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment are closely linked and interdependent [4]. In the context of pharmaceutical development, embracing One Health necessitates a fundamental shift from a singular focus on human therapeutic outcomes to a comprehensive ecological perspective that considers a drug's entire lifecycle—from design and manufacturing to consumption and environmental fate.

The imperative for this integrated approach stems from growing recognition of pharmaceutical impacts across species and ecosystems. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), one of the most pressing global health threats, exemplifies the interconnected nature of health challenges. The National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) in the United States demonstrates the value of a collaborative surveillance system that tracks antimicrobial resistance in humans, animals, and retail meat, with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) leading environmental components including monitoring surface water for AMR [5]. This holistic understanding reveals how antimicrobial resistance spreads across sectors, including into soil and water, providing data for more effective strategies to curb this growing threat [5].

The COVID-19 pandemic further underscored the necessity of integrated health approaches, with the response involving collaborations among public health, animal health, and environmental health officials from over 20 federal agencies, state and local partners, and universities [5]. The coordinated investigation of SARS-CoV-2 spread between people and animals, development of guidance, and shared research demonstrated how combining surveillance and genomic data from human and animal samples improves understanding of pathogen transmission across species [5]. This multidisciplinary approach provides a template for addressing complex health challenges throughout the pharmaceutical development pipeline.

One Health in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

Expanding Discovery Paradigms

Integrating One Health into pharmaceutical R&D requires expanding traditional discovery paradigms to include cross-species and environmental considerations. The One Health approach can accelerate biomedical research discoveries, enhance public health efficacy, expand the scientific knowledge base, and improve medical education and clinical care [5]. When properly implemented, it helps protect and save millions of lives in present and future generations [5].

Academic institutions are increasingly responding to this need through innovative educational programs. Purdue University, for instance, has announced new degrees including a Biomolecular Design major across chemistry, computer science, and biology that emphasizes discovery and manipulation of new biochemical molecules [6]. This program prepares students to design molecules for targeted drug delivery, personalized medicine, and climate-resistant plants, recognizing the interconnected nature of health challenges [6]. Such initiatives aim to create a talent pipeline capable of addressing complex health problems through integrated approaches.

The One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) and Quadripartite collaboration (FAO, UNEP, WHO, WOAH) work to increase the adoption of the One Health approach in national, regional, and international health policies through intersectoral political and strategic leadership [4]. This includes operationalizing responses, scaling up country support, strengthening capacities, and monitoring risks for early detection and response to emerging pathogens [4]. These frameworks provide essential guidance for pharmaceutical companies seeking to align their R&D practices with One Health principles.

Environmental Risk Assessment in Drug Development

Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) provides a formal framework for evaluating potential environmental impacts of pharmaceuticals, consistent with the environmental protection aspects of One Health. The EPA defines ERA as "the process for evaluating how likely it is that the environment might be impacted as a result of exposure to one or more environmental stressors" [7]. This structured approach includes three primary phases, each with specific components relevant to pharmaceutical assessment, as shown in the workflow below:

Figure 1: The three-phase Ecological Risk Assessment workflow for pharmaceuticals, adapted from EPA guidelines [7].

The planning phase establishes the overall approach through dialogue between risk managers, risk assessors, and stakeholders to identify risk management goals, natural resources of concern, and assessment scope [7]. For pharmaceuticals, this typically involves identifying potential environmental compartments (aquatic, terrestrial, soil) that may be exposed to active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and their metabolites through manufacturing discharges, patient use, or improper medication disposal.

During problem formulation, assessors determine which plants and animals are at potential risk, specify assessment endpoints (e.g., survival of fish populations, soil microbial diversity), and define measures and models for risk evaluation [7]. For pharmaceuticals, this includes characterizing the drug's mode of action, potential for bioaccumulation, and persistence in different environmental media.

The analysis phase consists of two components: exposure assessment (determining which organisms are exposed and to what degree) and effects assessment (reviewing research on exposure-level and adverse effects relationships) [7]. This phase leverages both traditional toxicological studies and emerging New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that can provide human-relevant toxicity data while reducing animal testing [8].

Risk characterization integrates exposure and effects assessments to estimate the likelihood of adverse ecological effects and describe uncertainties in the assessment [7]. This phase produces the critical risk quotient that informs regulatory decisions and potential risk management strategies.

Strategic Implementation Frameworks

Interagency Collaboration Models

Effective implementation of One Health in pharmaceutical development requires robust collaborative frameworks that bridge traditional sectoral boundaries. The U.S. National One Health Framework to Address Zoonotic Diseases (2025–2029) represents a comprehensive model, involving the CDC, USDA, DOI, and 21 other federal agencies congressionally mandated to develop a strategic framework for addressing zoonotic diseases and interconnected health threats [5]. This initiative enhances preparedness through structured platforms for cross-agency communication, training, and information sharing to prevent, detect, and respond to outbreaks [5].

The Quadripartite collaboration between FAO, UNEP, WHO, and WOAH provides an international model for One Health implementation, currently developing a comprehensive One Health Joint Plan of Action [4]. This plan aims to mainstream and operationalize One Health at global, regional, and national levels; support countries in establishing national targets; mobilize investment; and enable collaboration across regions, countries, and sectors [4]. For pharmaceutical companies, engagement with these initiatives provides access to surveillance data, emerging threat intelligence, and regulatory harmonization opportunities.

The One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System (OHHABS) demonstrates successful cross-agency collaboration, involving CDC, EPA, NOAA, and state partners in an integrated surveillance system for reporting human and animal illnesses associated with harmful algal blooms [5]. This model creates better national estimates of public health burdens by combining human and animal health reports while leveraging NOAA's environmental condition data to predict and prevent HABs [5]. Similar approaches could be applied to pharmaceutical environmental monitoring.

Academic-Industry Partnerships

Strategic partnerships between academic institutions and industry represent a powerful mechanism for advancing One Health integration in pharmaceutical development. Purdue University's series of initiatives exemplifies this approach, including new degrees in advanced chemistry and pharmaceutical engineering, faculty recruitment in interdisciplinary fields, and a Learning and Training Center in Eli Lilly and Company's new Medicine Foundry [6]. These investments aim to unite research and innovation across human, animal, and plant health [6].

The William D. and Sherry L. Young Institute for the Advanced Manufacturing of Pharmaceuticals at Purdue demonstrates how industry-academia partnerships can drive One Health objectives, uniting faculty in overhauling pharmaceutical manufacturing with a goal of reducing costs and expanding access to innovative drugs [6]. Similarly, the Low Institute for Therapeutics works toward accelerating lifesaving therapeutics from the lab into the world by funding necessary early-stage trials [6]. These models highlight the role of strategic philanthropy in advancing One Health integration.

Purdue's One Health Innovation District in downtown Indianapolis, developed in partnership with Elanco Animal Health Inc., envisions a globally recognized research hub that embodies One Health principles [6]. Such districts create physical ecosystems where researchers, startups, and established companies can collaborate across traditional health domains, accelerating the translation of One Health concepts into practical pharmaceutical applications.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Advanced Assessment Techniques

Next-generation ecological risk assessment incorporates innovative methodologies that align with One Health principles by providing more human-relevant data while reducing animal testing. The Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) is developing, refining, and communicating scientific tools needed to support ecological risk assessment globally, with a focus on alternative, non-animal testing methods [8]. Their approach includes several cutting-edge methodologies:

The Ecotoxicology Endocrine Toolbox project, a collaboration between HESI and NC3Rs, focuses on assessing available in vitro and in silico methods (New Approach Methodologies - NAMs) to evaluate chemicals that may act via endocrine pathways in fish and amphibians [8]. This includes systematic evaluation of NAMs, analysis of historical control data from in vivo endocrine disrupting chemical tests, and Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) studies [8].

The Avian Bioaccumulation and Biotransformation working group has funded a multi-year project at the University of Saskatchewan to develop a bird in vitro biotransformation assay [8]. This research aims to provide reliable alternatives to traditional animal testing while generating data relevant to wildlife exposure scenarios. Similarly, the Fish Bioaccumulation and Biotransformation group is scoping needs and advancements in fish toxicokinetics and PBPK (Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic) models to organize and present these models more transparently for end users [8].

The EnviroTox Database and Tools group is developing strategies to update and augment the EnviroTox database while refining applicable tools for ecological risk assessment [8]. This includes work on mode of action classifications, acute-to-chronic ratios for extrapolation, and understanding water quality criteria values globally [8]. These resources provide critical data infrastructure for One Health-informed pharmaceutical assessment.

Integrated Surveillance Systems

Implementing comprehensive surveillance systems that track pharmaceuticals across human, animal, and environmental compartments is essential for One Health integration. The following table summarizes key surveillance approaches and their applications:

Table 1: Integrated Surveillance Systems for One Health Pharmaceutical Assessment

| System Name | Key Components | One Health Application | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) [5] | Tracks AMR in humans, animals, retail meat; EPA monitors surface water for AMR | Reveals how antimicrobial resistance spreads across sectors including environment | Provides data for more effective strategies to curb AMR threat |

| One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System (OHHABS) [5] | Integrated surveillance for human/animal illnesses from harmful algal blooms; combines human/animal health reports with environmental data | Creates better national estimate of public health burden by combining human and animal health data | Allows NOAA environmental data to help predict and prevent HABs |

| Wildlife Health Monitoring [9] | Tools for wildlife health monitoring in protected area planning and management | Supports strengthening environmental and wildlife health into One Health approaches | Provides practical guidance for national authorities, civil society and IPLCs |

| Environmental Surveillance of APIs | Monitoring surface water, soil, and biota for pharmaceutical residues | Identifies exposure pathways and potential ecological impacts | Informs risk assessment and targeted interventions |

These surveillance systems generate critical data on the fate and effects of pharmaceuticals across ecosystems, enabling more comprehensive risk assessment and targeted interventions. The IUCN session on One Health tools highlights practical approaches for strengthening environmental and wildlife health integration into One Health frameworks, including risk analysis and wildlife health monitoring [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing One Health approaches in pharmaceutical development requires specialized research tools and reagents that facilitate cross-species and environmental assessments. The following table details essential materials and their functions in One Health-relevant research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for One Health Pharmaceutical Assessment

| Research Reagent | Function | One Health Application |

|---|---|---|

| In vitro biotransformation assays [8] | Measures metabolic conversion of pharmaceuticals using cellular systems rather than live animals | Provides reliable alternatives to traditional animal testing for bioaccumulation assessment in birds and fish |

| PBPK (Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic) models [8] | Mathematical models simulating absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of chemicals across species | Enables cross-species extrapolation of pharmaceutical effects and supports fish bioaccumulation assessment |

| Endocrine activity NAMs (New Approach Methodologies) [8] | In vitro and in silico methods for detecting endocrine disrupting potential | Evaluates chemicals that may act via endocrine pathways in fish and amphibians without extensive animal testing |

| EnviroTox Database [8] | Curated database of ecotoxicological information for chemical hazard assessment | Supports ecological risk assessment with high-quality data and tools for threshold of toxicological concern approaches |

| Integrated Approaches for Testing and Assessment (IATA) [8] | Structured frameworks for collecting, generating, and evaluating various types of bioaccumulation data | Enhances prediction of chemicals' ecological effects through weight-of-evidence approaches |

| AirNow and PurpleAir sensors [5] | Air quality monitoring networks measuring particulate matter and pollutants | Identifies public health risks from wildfire smoke and other environmental stressors affecting multiple species |

| Chlorphenoxamine | Chlorphenoxamine, CAS:77-38-3, MF:C18H22ClNO, MW:303.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Octanohydroxamic acid | Octanohydroxamic Acid | C8H17NO2 | 7377-03-9 | Octanohydroxamic acid is a key reagent for energy storage material synthesis and mineral flotation research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for personal use. |

These tools enable researchers to assess pharmaceutical impacts across the One Health spectrum, supporting the development of safer products with reduced ecological impacts. The movement toward "a coordinated network of experts interested in ecotoxicology" and a shift "from a 1:1 replacement of existing methods towards an integrative assessment strategy" reflects the evolving nature of these scientific tools [8].

Data Integration and Analysis Frameworks

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Effective One Health integration requires robust frameworks for synthesizing quantitative data from multiple domains. The following table illustrates the types of quantitative metrics that should be integrated throughout the pharmaceutical development lifecycle:

Table 3: Quantitative Data Integration for One Health Pharmaceutical Assessment

| Data Category | Human Health Metrics | Animal Health Metrics | Environmental Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Parameters | IC50, TD50, therapeutic index | LC50, EC50, species sensitivity distributions | PNEC, QSAR predictions, biodegradation rates |

| Exposure Parameters | Plasma concentrations, clearance rates, metabolite profiles | Tissue residues, wildlife exposure models | PEC, measured environmental concentrations, bioaccumulation factors |

| Efficacy Parameters | Clinical endpoints, biomarker responses, quality of life measures | Zootechnical parameters, disease incidence reduction | Ecosystem function preservation, biodiversity maintenance |

| Resistance Development | AMR incidence in clinical isolates, treatment failure rates | AMR in animal pathogens, zoonotic transmission | AMR in environmental bacteria, resistance gene transfer |

The One Health approach emphasizes collecting and integrating these diverse data streams to inform decision-making throughout pharmaceutical development. This integrated data approach enables identification of potential trade-offs and synergies across domains, supporting development of pharmaceuticals that optimize health outcomes across human, animal, and environmental dimensions.

Cross-Sectoral Impact Assessment

The fundamental relationships between pharmaceutical development activities and One Health outcomes can be visualized through the following impact pathway:

Figure 2: Pharmaceutical impact pathways across One Health domains throughout development lifecycle.

This conceptual framework illustrates how decisions at each stage of pharmaceutical development create ripple effects across human, animal, and environmental health domains. The One Health approach emphasizes systematic consideration of these interconnected impacts rather than optimizing for single-domain outcomes.

The EPA's One Health Coordination Team (OHCT), established in Fall 2022, exemplifies how regulatory agencies are institutionalizing this integrated assessment approach [10]. The National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine has made recommendations to EPA for further expanding the One Health concept across the Office of Research and Development, particularly for addressing complex environmental challenges like wildfire, hazardous algal blooms, and antimicrobial resistance [10]. These institutional developments create important reference points for pharmaceutical companies developing their own One Health assessment capabilities.

Integrating the One Health concept into pharmaceutical development represents both an ethical imperative and strategic opportunity for the industry. This approach recognizes that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems are inextricably linked, and that pharmaceuticals—while delivering tremendous benefits—can create unintended consequences across this interconnected system [4]. The frameworks, methodologies, and tools outlined in this technical guide provide a roadmap for systematically incorporating One Health principles throughout the pharmaceutical development lifecycle.

The economic case for this integration is compelling. As noted by the One Health Initiative team, "proactive, multisectoral approaches are cheaper in the long run than reactionary, fragmented responses" [5]. The immense economic costs of COVID-19 were mitigated using One Health measures, and similar approaches can prevent or lessen future pandemics while addressing other cross-sectoral health threats [5]. For pharmaceutical companies, early integration of One Health principles can reduce downstream costs associated with environmental remediation, product restrictions, and reputational damage.

Looking forward, emerging capabilities in advanced chemistry, artificial intelligence, and automated discovery platforms create unprecedented opportunities to embed One Health considerations into fundamental research and development processes [6]. The movement toward "clean chemistry principles" that prepare graduates "to design efficient, scalable solutions that reduce waste and energy" exemplifies this evolution [6]. By embracing these innovations within a One Health framework, the pharmaceutical industry can deliver transformative health solutions while honoring its responsibility to planetary health.

Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) is a systematic process required by regulatory agencies to evaluate the potential impact of human medicinal products (HMPs) on ecosystems. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) both recognize that active pharmaceutical ingredients can persist in the environment and potentially affect aquatic and terrestrial organisms. While both agencies aim to protect public health and the environment, their regulatory approaches, legal frameworks, and procedural requirements differ significantly. The ERA process is designed to identify, characterize, and quantify potential environmental risks arising from the manufacture, use, and disposal of pharmaceuticals, thereby enabling the implementation of appropriate risk mitigation measures where necessary [11].

The legislative requirement for ERAs in the EU has been established for over 15 years under Article 8(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC, which mandates evaluation of potential environmental risks posed by medicinal product use [11]. The EMA's revised guideline on ERA comes into effect on 01 September 2024, representing a significant update to the original 2006 guidance. In contrast, the FDA's approach to environmental assessment for pharmaceuticals is governed under different regulatory statutes and exhibits distinct procedural characteristics [12].

Comparative Analysis of EMA and FDA ERA Frameworks

The following table summarizes the key differences and similarities between the EMA and FDA requirements for Environmental Risk Assessment:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of EMA and FDA ERA Requirements

| Aspect | EMA ERA Framework | FDA ERA Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Basis | Directive 2001/83/EC, Article 8(3) [11] | Varied statutory authorities depending on product type |

| Scope of Products | All new Marketing Authorisation Applications (MAAs) for human medicinal products, including generics [11] | Drugs, biologics, medical devices, foods, cosmetics [12] |

| Assessment Trigger | Mandatory for all new MAAs regardless of PEC [11] | Typically triggered by specific criteria or concerns |

| Assessment Structure | Tiered approach: Phase I → Phase II (Tiers A & B) [11] | Case-specific assessment approach |

| Key Criteria | PECsw ≥ 0.01 μg/L triggers Phase II; PBT assessment [11] | Focus on environmental impact statements |

| Hazard Assessment | Mandatory PBT/vPvB assessment for all active substances [11] | Integrated within overall risk evaluation |

| Geographical Application | Across EU member states with possible national adaptations [12] | Centralized for the United States [12] |

EMA ERA Requirements: Detailed Framework

The Tiered Assessment Approach

The EMA's ERA process follows a tiered, step-wise approach that begins with a preliminary assessment and progresses to more detailed testing only when potential risks are identified. This structured methodology ensures that resources are focused on products with the greatest potential environmental impact [11].

Phase I Assessment serves as an initial screening step. It involves calculating the Predicted Environmental Concentration in surface water (PECsw) based on the product's use characteristics and properties. The key criteria for proceeding to Phase II is a PECsw ≥ 0.01 μg/L, though this may be refined using a market penetration factor (FPEN) that represents the fraction of the population receiving the active substance daily. Specific assessment strategies are mandatory for particular substance groups, including antibacterials, antiparasitics, and endocrine active substances (EAS). For non-natural peptides/proteins that are readily biodegradable, Phase II assessment is not required [11].

Phase II Assessment involves comprehensive experimental studies to characterize the environmental fate and effects of the substance. This phase is divided into two tiers:

Tier A requires studies on physico-chemical properties, environmental fate, and ecotoxicological effects. The outcomes determine whether additional risk assessments for soil, groundwater, and secondary poisoning are necessary [11].

Tier B focuses on refining PEC calculations when risks are identified in Tier A, through more sophisticated modeling or additional data collection [11].

Hazard Assessment: PBT/vPvB Evaluation

A distinctive feature of the EMA ERA framework is the mandatory assessment of Persistence, Bioaccumulation, and Toxicity (PBT) or very Persistent and very Bioaccumulative (vPvB) properties for all active substances, largely independent of their PEC values. This hazard assessment identifies substances with intrinsic properties that could pose long-term environmental risks, even at low concentrations [11].

The PBT assessment follows a tiered testing strategy beginning with a screening assessment of the octanol/water partition coefficient (log Kow) in Phase I. If the log Kow > 4.5, a definitive PBT assessment is required in Phase II, following criteria defined under the REACH regulation (Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006). Notably, even substances that don't trigger the definitive assessment may still require PBT evaluation if Phase II results demonstrate that bioaccumulation and toxicity criteria are met [11].

Revised EMA Guidelines: Key Updates for 2024

The revised EMA guideline effective September 2024 introduces several important updates from the original 2006 guidance:

- Broader Application: Generics are no longer eligible for waivers from ERA requirements [11].

- Enhanced Testing Requirements: Most fate and effect testing has been moved to Phase II Tier A, with Tier B focusing on exposure refinement [11].

- New Assessment Sections: Inclusion of secondary poisoning assessment to estimate accumulation in food chains [11].

- Technical Refinements: Updated triggers for additional studies and more detailed technical specifications for conducted studies [11].

- Data Requirements: Emphasis on Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) compliance and use of OECD or comparable international validated test guidelines [11].

- Data Sharing: Encouragement of data sharing between applicants to avoid unnecessary repetition of animal studies, consistent with 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) [11].

The following diagram illustrates the complete EMA ERA assessment process, including both risk and hazard assessment pathways:

FDA ERA Requirements: Detailed Framework

Regulatory Basis and Assessment Approach

The FDA's approach to environmental assessment for pharmaceuticals operates under different statutory authorities than the EMA framework. While the specific requirements for ERA are less explicitly detailed in the available search results, the FDA's overall regulatory philosophy and risk management procedures provide context for understanding its approach to environmental assessment [12].

Unlike the EMA's standardized tiered testing strategy, the FDA employs a more case-specific assessment approach that may be triggered by particular product characteristics or environmental concerns. The FDA's regulatory scope is notably broader than EMA's, encompassing drugs, biologics, medical devices, foods, and cosmetics, which necessitates a flexible framework that can accommodate diverse product types [12].

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS)

While not exclusively environmental in focus, the FDA's Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) program represents the agency's structured approach to managing known or potentially serious risks of medications. The FDA can require a REMS "at any point during a product life cycle" to ensure that a drug's benefits outweigh its risks. REMS programs are not designed to mitigate all adverse events but focus on "preventing, monitoring, and managing a specific serious risk" through targeted interventions [12].

REMS programs may include various components such as "medication guides, communication plans, and elements to ensure safe use (ETESU)". These elements are tailored to the specific risks identified and may include special certification requirements for dispensers or evidence of safe-use conditions. This risk-based, targeted approach reflects the FDA's overall philosophy toward risk management, which likely extends to environmental assessments [12].

Experimental Protocols and Testing Methodologies

Phase I Tier Testing Protocols

The initial Phase I assessment follows a standardized decision-tree approach with specific experimental and calculation protocols:

PECsw Calculation Protocol:

- Data Requirements: Maximum daily dose, market penetration factor (FPEN), wastewater treatment plant removal rate, dilution factor

- Calculation Method: PECsw = (A * FPEN * (1 - R)) / (W * D) Where A = amount used per day, FPEN = market penetration factor (default 0.01), R = removal rate in wastewater treatment, W = wastewater volume per capita per day, D = dilution factor

- Decision Threshold: PECsw ≥ 0.01 μg/L triggers Phase II assessment [11]

PBT Screening Protocol:

- Test System: OECD Test Guideline 107 or 117 for partition coefficient determination

- Key Parameter: Logarithmic octanol-water partition coefficient (log Kow)

- Decision Threshold: log Kow > 4.5 triggers definitive PBT assessment [11]

Phase II Tier A Testing Requirements

Phase II Tier A involves comprehensive environmental testing across multiple domains:

Table 2: Phase II Tier A Experimental Requirements

| Assessment Area | Required Tests | Standard Guidelines | Key Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Fate | Ready biodegradability; Hydrolysis; Adsorption/desorption | OECD 301; OECD 111; OECD 106 | Degradation half-lives; Koc |

| Aquatic Ecotoxicity | Algae growth inhibition; Daphnia reproduction; Fish toxicity | OECD 201; OECD 202; OECD 203 | EC50; NOEC |

| Sediment Toxicity | Sediment-dwelling organism toxicity | OECD 218/219 | EC50 |

| STP Effects | Microbial community inhibition | OECD 209 | EC50 |

| Soil Toxicity | Plant emergence; Earthworm reproduction | OECD 208; OECD 222 | EC50; NOEC |

Phase II Tier B Refinement Protocols

When Tier A testing identifies potential risks (PEC/PNEC > 1), Tier B provides refinement options:

Exposure Refinement Methods:

- Regional Assessment: Site-specific PEC calculations considering local demographics, hydrological conditions, and wastewater treatment infrastructure

- Monitoring Data: Use of actual environmental monitoring data from similar compounds or regions

- Advanced Modeling: Implementation of sophisticated fate models accounting for seasonal variations, metabolic transformation, and spatial distribution

Effects Refinement Methods:

- Species Sensitivity Distribution (SSD): Multi-species assessment to derive more realistic PNEC values

- Mesocosm Studies: Higher-tier ecosystem-level studies for substances with potential community-level effects

- Mode-of-Action Testing: Investigation of specific toxicological mechanisms to support extrapolation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ERA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in ERA | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Quality control for analytical measurements; Method validation | All chemical analysis phases |

| OECD Test Media | Standardized growth and exposure media for ecotoxicity tests | Algae, daphnia, and fish toxicity assays |

| Synthetic Sewage Sludge | Simulation of sewage treatment plant conditions | STP inhibition studies |

| Passive Sampling Devices | Measurement of bioavailable contaminant fractions | Field validation studies |

| Cryopreserved Organisms | Consistent biological test materials | Ecotoxicity testing |

| Metabolite Standards | Identification and quantification of transformation products | Environmental fate studies |

| Quality Control Materials | Verification of test system performance | All GLP-compliant testing |

| Molecular Probes | Assessment of specific toxicological mechanisms | Mode-of-action investigations |

| Adenomycin | Adenomycin, CAS:76174-56-6, MF:C25H39N7O18S, MW:757.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fosmidomycin | Fosmidomycin, CAS:66508-53-0, MF:C4H10NO5P, MW:183.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The EMA and FDA regulatory frameworks for Environmental Risk Assessment represent complementary approaches to addressing the potential environmental impacts of pharmaceuticals. The EMA employs a highly structured, tiered testing strategy with clearly defined triggers and decision points, mandatory for all new marketing authorization applications. In contrast, the FDA utilizes a more flexible, case-specific approach that integrates environmental considerations into broader risk management frameworks like REMS.

The recently revised EMA guideline (effective September 2024) significantly enhances the robustness of ERA requirements in the EU, particularly through expanded testing requirements, mandatory PBT assessment for all active substances, and removal of waivers for generic products. Both regulatory frameworks emphasize the importance of scientifically sound, well-documented environmental assessments that align with international testing standards and incorporate appropriate risk mitigation measures.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these regulatory frameworks is essential for successful product development and approval. The divergent approaches between EMA and FDA necessitate careful planning and execution of environmental assessment strategies throughout the product lifecycle, from early development through post-marketing surveillance.

Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) is a formal process used to evaluate the likelihood that the environment may be adversely impacted by exposure to one or more environmental stressors, which can include chemicals, biological agents, or physical changes [7]. This scientific framework connects the potential effects of human activities on ecological systems and provides a structured approach for environmental decision-making. The process is inherently iterative, designed to incorporate increasing levels of detail to reduce uncertainty in risk estimates [2].

Within the regulatory context, ERA supports critical actions including the regulation of hazardous waste sites, industrial chemicals, pesticides, and watershed management [7]. The assessment process can be either prospective (predicting the likelihood of future effects) or retrospective (evaluating the likelihood that observed effects are caused by past or ongoing exposure) [7]. A fundamental challenge in ERA lies in bridging the gap between what can be practically measured in controlled settings and the ultimate ecological values that society seeks to protect [2]. This guide examines the core concepts—stressors, assessment endpoints, and measurement endpoints—that form the foundation for addressing this challenge.

Core Conceptual Framework

The Interrelationship of Core Concepts

The three core concepts of Stressors, Assessment Endpoints, and Measurement endpoints form a logical chain that connects human activities to ecological effects and, ultimately, to what society values. This relationship is foundational to the entire ERA process.

- Stressors represent the initial cause for concern—the physical, chemical, or biological entities that can trigger adverse effects. Establishing exposure is critical; if there is no exposure, there can be no risk [13].

- Assessment Endpoints are the explicit expressions of the environmental values to be protected. They operationalize broad protection goals into specific ecological entities and their attributes [14].

- Measurement Endpoints are the measurable responses used to infer the status of the assessment endpoints. They are the practical, quantifiable metrics collected in the field or laboratory [2].

This framework ensures that the scientific data collected (measurement endpoints) is directly relevant to the ecological values being protected (assessment endpoints) and the potential causes of harm (stressors).

The Role of Core Concepts in the ERA Process

The core concepts are integrated throughout the three primary phases of an ERA, which are Planning, Problem Formulation, Analysis, and Risk Characterization [7]. Each phase utilizes these concepts differently to progressively refine the understanding of risk.

Table: Role of Core Concepts in the ERA Phases

| ERA Phase | Role of Stressors | Role of Assessment Endpoints | Role of Measurement Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning & Problem Formulation | Identified as potential concerns; key characteristics (intensity, duration, frequency) are defined [13]. | Selected based on ecological relevance, societal values, and potential susceptibility to stressors [7]. | Not yet selected; conceptual models link stressors to potential effects on assessment endpoints. |

| Analysis | Exposure is characterized by examining sources, distribution, and extent of contact with ecological receptors [14]. | Guide the effects characterization; the stressor-response profile links data to the assessment endpoint [14]. | Selected and measured; provide quantitative data on exposure and ecological effects for the risk characterization [2]. |

| Risk Characterization | The link between stressor exposure and effects is quantified and interpreted [13]. | The significance of effects on the assessment endpoints is interpreted, considering uncertainties [7]. | The measured data are integrated and compared to evaluate the likelihood and magnitude of adverse effects. |

Defining and Classifying Stressors

Stressor Definition and Key Characteristics

In Ecological Risk Assessment, a stressor is any physical, chemical, or biological entity that can induce an adverse response in an ecological system [7]. Stressors originate from human activities and can induce a range of effects from the molecular to the ecosystem level. The potential for risk materializes only when a stressor co-occurs with or contacts an ecological receptor [13].

When identifying stressors, risk assessors characterize them by several key attributes [13]:

- Type: The fundamental nature of the stressor (chemical, biological, or physical).

- Intensity: The concentration (for chemicals) or magnitude of the stressor.

- Duration: The length of time the stressor is present (short-term or long-term).

- Frequency: How often the exposure occurs (single event, episodic, or continuous).

- Timing: The timing of exposure relative to seasonal cycles or critical life stages of organisms.

- Scale: The spatial extent and heterogeneity of the stressor's distribution.

Classification of Stressors with Examples

Stressors are broadly categorized into three types, each with distinct properties and mechanisms of impact.

Table: Classification and Examples of Ecological Stressors

| Stressor Type | Definition | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical | Substances that cause adverse effects through toxicological mechanisms. | Pesticides, industrial chemicals, metals, nutrients (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus) [7] [2]. |

| Physical | Agents or activities that directly alter, degrade, or eliminate the physical habitat. | Habitat loss or fragmentation (e.g., logging, land development), construction of dams, changes in sediment load, changes in water temperature [15]. |

| Biological | Living organisms that cause harm by altering species composition or ecosystem function. | Introduction of invasive species (e.g., non-native oysters), pathogens, genetically modified organisms [7]. |

A single human activity can often release multiple stressors. For instance, building a logging road (a physical stressor) can lead to secondary stressors such as increased suspended sediments in waterways and changes in stream temperature, which may become the primary concern for aquatic life [15]. Furthermore, organisms in the environment are typically exposed to multiple stressors simultaneously, both chemical and non-chemical, and their combined effects can be complex and confounding [16].

Defining Assessment Endpoints and Measurement Endpoints

Assessment Endpoints

Assessment Endpoints are "explicit expressions of the actual environmental values that are to be protected" [2]. They operationalize broad management goals into specific, definable ecological entities. An ideal assessment endpoint clearly defines both the ecological entity (e.g., a species, a community, a habitat) and its key attribute (e.g., reproduction, survival, biodiversity) that is potentially at risk [14].

- Role in ERA: They are the ultimate focus of the risk assessment, providing the benchmark against which the significance of effects is judged [7].

- Selection Criteria: They should be ecologically relevant, socially significant, and susceptible to the identified stressors [7]. For example, the public often values the protection of vertebrate species and critical ecosystem services [2].

Examples of Assessment Endpoints [7] [14]:

- The continued existence of a sustainable fishery population.

- Fish species diversity in lakes.

- The sustainable habitat function of a forest.

- The survival and reproduction of an endangered bird species.

Measurement Endpoints

Measurement Endpoints are "measurable responses to a stressor that are related to the valued characteristic chosen as the assessment endpoints" [2]. They are the quantitative or qualitative measures collected during the Analysis phase of an ERA.

- Role in ERA: They provide the empirical data used to estimate effects and exposure, forming the evidence base for the risk characterization [14] [2].

- Relationship to Assessment Endpoints: A measurement endpoint is a surrogate for an assessment endpoint. While they are seldom identical, a strong, well-understood correlative or causal relationship must link them.

Examples of Measurement Endpoints [2]:

- A 96-hour LCâ‚…â‚€ (lethal concentration for 50% of a population) for Daphnia magna in a laboratory test.

- A No Observed Adverse Effect Concentration (NOAEC) from a life-cycle study.

- A reduction in brood size or population growth rate in a model organism.

- In situ measures of population biomass or a biodiversity index.

Comparative Analysis: Assessment vs. Measurement Endpoints

The distinction between assessment and measurement endpoints is a critical source of uncertainty in ERA, as it represents an extrapolation from what is measured to what is protected.

Table: Distinguishing Assessment Endpoints from Measurement Endpoints

| Characteristic | Assessment Endpoint | Measurement Endpoint |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The environmental value to be protected. | The measurable response used to infer status of the assessment endpoint. |

| Nature | Conceptual; defines what is important. | Operational; defines what is measurable. |

| Level of Specificity | Broad, defined by management and societal goals. | Specific, defined by scientific and logistical practicality. |

| Example | "Sustainable salmon population in River X." | "20% reduction in egg-to-fry survival rate of salmon." |

| Role in ERA | The protection goal that frames the assessment. | The source of data that informs the assessment. |

A key challenge is that the most readily available measurement endpoints (e.g., survival of a standard test species in a lab) are often far removed, in terms of biological organization and ecological complexity, from the desired assessment endpoints (e.g., ecosystem function and biodiversity) [2]. This "mismatch" necessitates the use of extrapolation models and assessment factors to bridge the gap, introducing uncertainty into the risk estimate.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The ERA Workflow: From Planning to Risk Characterization

The U.S. EPA's structured approach to ERA integrates the core concepts into a sequential, phased process. This workflow ensures a systematic evaluation from initial planning through to risk estimation.

Phase 1: Problem Formulation

Problem Formulation establishes the foundation for the entire assessment. It is a collaborative phase involving risk managers, risk assessors, and stakeholders [7].

Protocol Steps:

- Identify Management Goals and Options: Define the regulatory or management context and the decisions the ERA will inform [7].

- Identify Stressors of Concern: Specify the type, intensity, duration, and other key characteristics of the stressors [13].

- Select Assessment Endpoints: Choose the ecological entities and their attributes that are valued and potentially at risk [7] [14].

- Develop a Conceptual Model: Create a written description and visual representation (e.g., a flow diagram) of predicted relationships between ecological entities and the stressors. This model hypothesizes how exposure might occur and what effects might result [13].

- Create an Analysis Plan: Specify the measurement endpoints, models, and data required to proceed to the Analysis phase [7].

Phase 2: Analysis

The Analysis phase is a technical evaluation of data to characterize exposure and ecological effects. It consists of two parallel and complementary lines of evidence [14].

Protocol A: Exposure Characterization The goal is to produce an Exposure Profile, a summary of the magnitude and spatial and temporal patterns of exposure [14].

- Evaluate Sources and Releases: Identify the origins and release mechanisms of the stressor.

- Assess Environmental Distribution: Evaluate the fate and transport of the stressor to understand its distribution in the environment (e.g., using tools from the EPA EcoBox Stressors Tool Set) [14].

- Determine Co-occurrence and Contact: Estimate the intensity, spatial extent, and temporal pattern of contact between the stressor and ecological receptors. "Co-occurrence" is particularly relevant for physical stressors where direct contact may not be necessary for an effect to occur [15] [13].

- Address Uncertainty: Describe the impact of variability and uncertainty on the exposure estimates.

Protocol B: Ecological Effects Characterization The goal is to produce a Stressor-Response Profile, which summarizes the data on the effects of a stressor and its relationship to the assessment endpoint [14].

- Describe Effects: Compile and review available research on the adverse effects elicited by the stressor.

- Evaluate Stressor-Response Relationships: Analyze how the magnitude of ecological effects changes with varying stressor levels.

- Assess Evidence for Causality: Weigh the evidence linking the stressor to the observed or predicted effects.

- Link to Assessment Endpoints: Establish a quantitative or qualitative relationship between the measured effects and the selected assessment endpoints.

Phase 3: Risk Characterization

Risk Characterization integrates the exposure and stressor-response profiles to produce a complete picture of risk [7].

Protocol Steps:

- Risk Estimation: Compare the exposure levels for the ecological receptors of concern with the data on expected effects for those same receptors [7]. This can be a qualitative comparison or a quantitative estimation of the probability and severity of effects.

- Risk Description: Interpret the risk results by describing [7]:

- Whether harmful effects are expected on the plants and animals of concern.

- The nature and scale of those effects, including primary (direct) and secondary (indirect) consequences [13].

- How uncertainties, data gaps, and natural variation might affect the assessment.

- A conclusion regarding the likelihood of adverse ecological effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents and Models for ERA

This section details key resources, from conceptual frameworks to computational models, used in modern ecological risk assessment.

Table: Key Tools and Resources for Conducting ERA

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function and Application in ERA |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Frameworks | U.S. EPA Guidelines for Ecological Risk Assessment (1998) [14] [13] | Provides the standard framework and terminology for conducting ERAs in the United States. |

| Exposure Assessment Tools | EPA EcoBox (Stressor Tool Set, Exposure Pathways Tool Set) [14] [15] | Compiles resources, models, and data for characterizing the fate, transport, and exposure of stressors. |

| Effects Assessment Models | Dynamic Energy Budget (DEB) models [16] | Mechanistic models that simulate an organism's energy allocation, allowing for the integration of toxicant and multiple environmental stressors on life-history parameters. |

| Extrapolation Models | Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) [2] | Statistical models that estimate the concentration of a stressor that is protective of a specified fraction of species in a community. |

| Individual-Based Models (IBMs) coupled with DEB theory [16] | Allows for the extrapolation of individual-level effects to population-level consequences, accounting for individual variability and environmental conditions. | |

| Probabilistic Risk Tools | Prevalence Plots [16] | A graphical output from probabilistic assessments that shows an effect size (e.g., % population reduction) as a function of its cumulative prevalence (e.g., proportion of water bodies affected). Enhances communication of complex, multi-stressor risks. |

| Ditercalinium Chloride | Ditercalinium Chloride, CAS:74517-42-3, MF:C46H50Cl2N6O2, MW:789.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Vitamin K5 | Vitamin K5, CAS:83-70-5, MF:C11H11NO, MW:173.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

Integrating Multiple Stressors and Environmental Scenarios

A significant limitation of traditional ERA is its frequent focus on single stressors in isolation. In reality, ecosystems are subject to multiple stressors, including mixtures of chemicals and abiotic factors like temperature and food availability [16]. Newer approaches use environmental scenarios—qualitative and quantitative descriptions of the relevant environment—to integrate exposure conditions with ecological context, making ERA more geographically relevant and realistic [16]. Probabilistic frameworks are being developed to visualize the outcomes of these complex assessments using prevalence plots, which communicate the proportion of habitats expected to experience a given level of ecological effect [16].

Addressing the Level of Biological Organization Challenge

Ecological risk can be assessed at different levels of biological organization, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages [2].

Table: Comparison of ERA Across Levels of Biological Organization

| Level of Organization | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-organismal (Biomarkers) | High-throughput screening possible; reveals mechanisms of action [2]. | Large extrapolation distance to assessment endpoints; ecological significance often uncertain [2]. |

| Individual | Controlled, reproducible laboratory tests; standardized protocols [2]. | May not account for ecological interactions (e.g., competition, predation) and recovery processes [2]. |

| Population | More ecologically relevant; can capture density-dependent processes and recovery [2]. | More complex and resource-intensive to study; fewer standardized tests [2]. |

| Community & Ecosystem | High ecological relevance; can directly measure biodiversity and ecosystem function [2]. | High cost and complexity; highly variable; difficult to establish causality [2]. |

There is no single "ideal" level at which to conduct ERA. Next-generation ERA aims to compensate for the weaknesses at any single level by working simultaneously from the bottom up (using mechanistic models like DEB-IBMs to extrapolate from individuals to populations) and from the top down (using monitoring data and ecosystem models to identify risks that may be missed by lower-level tests) [16] [2]. This integrated approach, supported by continued advancements in ecological modeling, promises to make future ecological risk assessments more defensible, protective, and relevant.

The Problem Formulation Phase serves as the critical foundation of the Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) process, establishing the strategic direction, scope, and methodology for the entire assessment. This initial phase transforms a broadly defined environmental concern into a structured, actionable scientific investigation. It is during problem formulation that risk assessors and risk managers collaboratively articulate the purpose of the assessment, define the core problem, and develop a rigorous plan for analyzing and characterizing potential ecological risks [17]. This collaborative scoping ensures that the resulting assessment is not only scientifically defensible but also directly relevant to the environmental management decisions at hand. By integrating available information on stressors, potential effects, and ecosystem characteristics, problem formulation provides the essential framework that guides all subsequent analytical phases, ultimately determining the assessment's effectiveness and utility [7] [17].

The Planning Dialogue: Integrating Risk Management and Scientific Assessment

The planning stage initiates the ERA by fostering a structured dialogue between risk managers and risk assessors. This collaboration is essential for aligning scientific inquiry with regulatory and management needs. Risk managers, who bear the responsibility for implementing protective actions, contribute the decision-making context and identify the specific information required for their decisions. Concurrently, risk assessors provide insight into the scientific feasibility, methodological approaches, and data requirements for addressing the identified concerns [17].

Key Objectives of the Planning Dialogue

During this iterative process, the team establishes several critical elements [17]:

- Risk Management Goals and Options: Clearly define the environmental protection objectives and potential risk mitigation actions.

- Identification of Resources of Concern: Determine which natural resources (e.g., specific wildlife, aquatic systems, habitats) are potentially at risk and warrant protection.

- Assessment Scope and Complexity: Reach agreement on the spatial and temporal boundaries of the assessment, as well as the level of analytical rigor required.

- Team Roles and Resources: Clarify team member responsibilities and identify the resources available to complete the assessment.

This foundational dialogue ensures the subsequent problem formulation is tightly focused and efficiently designed to support informed environmental decision-making.

Core Components of Problem Formulation

Following planning, problem formulation involves a series of technical steps to define the assessment's scientific parameters. This process generates and evaluates preliminary hypotheses about why ecological effects have occurred, or may occur, due to human activities [17]. The core components developed during this phase are described below.

Information Integration and Evaluation

A comprehensive evaluation of available information is conducted, focusing on four key factors [17]:

- Stressors: The physical, chemical, or biological agents capable of causing adverse effects. Key considerations include the stressor's type, mode of action, toxicity, frequency, duration, distribution, and intensity.

- Sources: The origins of the stressors, including their status (e.g., active or inactive), spatial scale, and background environmental levels.

- Ecosystem and Receptor Characteristics: The ecosystems potentially at risk, including the identification of habitats, species present, and their life-history characteristics (e.g., mobility, sensitive life stages).

- Exposure Dynamics: The potential pathways and opportunities for receptors to encounter stressors, including the media involved (water, soil, air) and the timing of exposure relative to critical biological events.

Development of Assessment Endpoints

An assessment endpoint is an explicit expression of the environmental value to be protected, operationally defined by an ecological entity and its attributes [17]. These endpoints bridge general environmental values (e.g., "protect aquatic life") with specific, measurable ecological characteristics. They define what is to be protected and why it is considered valuable.

Examples of Assessment Endpoints include [7] [17]:

- The continued survival and reproduction of a threatened fish population.

- The maintenance of species diversity in lake communities.

- The sustainable provision of forest habitat for native wildlife.

Conceptual Model Development

A conceptual model is a written description and visual representation of the predicted relationships between ecological entities and the stressors to which they may be exposed [17]. It consists of two parts:

- Risk Hypotheses: Clear, testable statements describing the predicted relationships among a stressor, exposure, and the assessment endpoint.

- Conceptual Model Diagram: A visual illustration of these relationships, which clarifies exposure pathways and potential effects.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key components of the Problem Formulation Phase.

Analysis Plan

The final product of problem formulation is a detailed analysis plan. This document summarizes the decisions made during problem formulation and specifies how the risk hypotheses will be evaluated during the analysis phase. It explicitly outlines the assessment design, data needs, analytical methods, and measures that will be used to characterize risk. The plan also identifies data gaps and uncertainties, ensuring the analytical phase is targeted and efficient [17].

Methodologies and Protocols for Problem Formulation

The problem formulation phase relies on systematic protocols to ensure scientific rigor and transparency. The following table summarizes key methodological considerations for characterizing stressors and receptors, which are central to developing the conceptual model and analysis plan.

Table 1: Methodological Protocols for Stressor and Receptor Characterization in Problem Formulation

| Component | Characterization Protocol | Key Methodologies & Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Stressor Characterization | Evaluate the intrinsic properties and potential impact of the stressor. | - Toxicity Assessment: Review data on acute, chronic, and sublethal effects.- Persistence & Bioaccumulation: Determine environmental half-life and potential for bioconcentration/biomagnification [17].- Mode of Action: Identify the physiological or ecological mechanism of effect. |

| Exposure Assessment | Characterize the co-occurrence of the stressor and ecological receptors. | - Pathway Analysis: Identify routes of exposure (dermal, ingestion, inhalation) and media (water, soil, sediment) [17].- Spatiotemporal Modeling: Evaluate the distribution, frequency, and duration of the stressor in relation to receptor presence and life history. |

| Ecological Receptor Identification | Identify and prioritize the species, communities, or ecosystems to be protected. | - Habitat Mapping: Delineate habitats present in the assessment area.- Species Inventory: Document resident species, with emphasis on keystone species, sensitive species, and those with high trophic levels (e.g., predators susceptible to biomagnification) [17]. |

| Assessment Endpoint Selection | Define the specific ecological values to be protected. | - Ecological Relevance: The entity should be central to the ecosystem's structure/function.- Susceptibility: The entity should be sensitive to the stressor.- Societal/Significance: The entity should have recognized ecological, economic, or cultural value [7] [17]. |

Conducting a robust problem formulation phase requires leveraging a suite of conceptual and data resources. The following table outlines key tools and information sources essential for researchers and risk assessors.

Table 2: Essential Research and Assessment Tools for the Problem Formulation Phase

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples & Functions |

|---|---|

| Guidance Documents & Frameworks | - U.S. EPA Guidelines for Ecological Risk Assessment (1998): Provides the definitive regulatory framework and methodology for ERA in the United States [17].- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Test Guidelines: Standardized methods for chemical safety assessment, including ecological toxicity. |

| Ecological & Toxicological Data | - ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (EPA): A curated database of single-chemical toxicity data for aquatic and terrestrial life.- Regional Biological Assessment Reports: Provide data on local species composition, sensitive habitats, and background conditions. |

| Monitoring & Field Assessment | - Geographic Information Systems (GIS): Used for mapping stressors, sources, and habitats to evaluate spatial overlap and exposure pathways.- Field Sampling Design Tools: Protocols for Ecological Sampling (e.g., macroinvertebrate surveys, vegetation transects) and Chemical Monitoring to characterize stressor presence and intensity [1] [18]. |

| Stakeholder Engagement Protocols | - Structured Interview & Workshop Facilitation Guides: Methods for gathering information from resource managers, local experts, and the public to inform assessment endpoints and conceptual models [17]. |