Defining the Taxonomic Domain of Applicability in Adverse Outcome Pathways: A Framework for Cross-Species Prediction in Toxicology and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Taxonomic Domain of Applicability (tDOA) for Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs), a critical concept for enhancing the reliability of cross-species extrapolation in chemical...

Defining the Taxonomic Domain of Applicability in Adverse Outcome Pathways: A Framework for Cross-Species Prediction in Toxicology and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Taxonomic Domain of Applicability (tDOA) for Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs), a critical concept for enhancing the reliability of cross-species extrapolation in chemical risk assessment and drug development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of tDOA, detailing the importance of structural and functional conservation of key events. The article further examines advanced methodological approaches, including bioinformatics tools like SeqAPASS, for defining tDOA and demonstrates their application through case studies. It addresses common challenges and optimization strategies in tDOA determination and discusses the vital processes of validation and comparison with other New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). The synthesis offers a forward-looking perspective on integrating tDOA evaluation into regulatory science and predictive toxicology.

What is the Taxonomic Domain of Applicability? Foundational Concepts for AOP Development

In the context of the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework, the taxonomic domain of applicability (tDOA) defines the range of species for which a given AOP is biologically plausible [1] [2]. This concept has emerged as a critical component in modern toxicology and chemical risk assessment, bridging the gap between molecular initiating events and adverse outcomes across diverse species. The tDOA concept challenges the traditional assumption that taxonomic relatedness alone confers similar chemical susceptibility, instead focusing on the conservation of specific protein targets and biological pathways [1] [3]. As regulatory science moves toward animal-free testing methodologies, accurately defining tDOA has become essential for reliable cross-species extrapolation in both human toxicology and ecotoxicology [4] [2].

The fundamental premise underlying tDOA is that shared molecular targets and pathway conservation—rather than phylogenetic proximity—determine chemical susceptibility [3]. This paradigm shift enables researchers to predict chemical effects across taxonomically diverse species using computational approaches, supporting the One Health perspective that integrates human and ecosystem health [2]. The precise definition of tDOA allows for more scientifically grounded chemical safety assessments while reducing reliance on traditional animal testing [1] [4].

Computational Methodologies for tDOA Determination

Determining tDOA relies on computational new approach methodologies (NAMs) that leverage existing biological knowledge to predict chemical susceptibility across species. Two primary tools have emerged as standards in this field, each offering complementary approaches to tDOA definition.

Table 1: Core Computational Tools for tDOA Analysis

| Tool Name | Developer | Primary Function | Input Data | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SeqAPASS (Sequence Alignment to Predict Across Species Susceptibility) | US Environmental Protection Agency [1] | Predicts chemical susceptibility across species based on protein sequence and structural similarity [1] [3] | Protein sequence data from NCBI database [2] | Susceptibility predictions across taxonomic groups [1] |

| G2P-SCAN (Genes to Pathways - Species Conservation Analysis) | Unilever [1] [3] | Estimates biological pathway conservation across species [1] [3] | Human gene inputs [1] | Pathway conservation across 7 model species [1] |

Tool Integration and Workflow

The power of these computational approaches lies in their strategic integration, creating a weight-of-evidence framework that enhances confidence in tDOA predictions [1] [3]. The typical workflow begins with SeqAPASS, which utilizes protein sequence information to extrapolate chemical susceptibility across the diversity of species with available protein sequence data [1]. This tool expands the biological space in which toxicity predictions are possible by identifying conserved molecular targets across taxonomic groups [3].

G2P-SCAN complements this approach by providing biological pathway-level information from human gene inputs, supporting inferences of pathway conservation across seven species commonly used in chemical safety assessment: humans (Homo sapiens), mice (Mus musculus), rats (Rattus norvegicus), zebrafish (Danio rerio), fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), roundworms (Caenorhabditis elegans), and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) [1]. The combination of these tools generates multiple lines of evidence associated with chemical effects on biological pathways and taxonomic relevance, significantly strengthening tDOA predictions [1] [3].

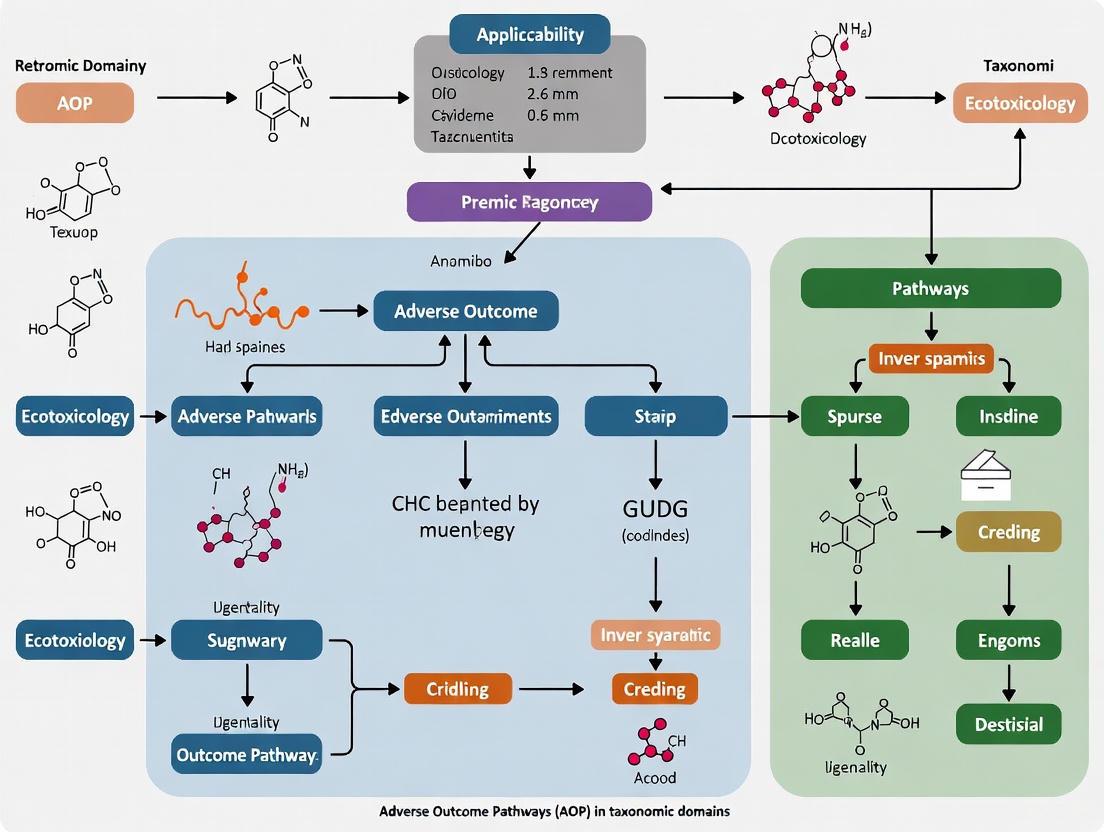

Figure 1: Integrated Workflow for tDOA Definition in AOP Development

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Standardized Methodological Approach

The experimental protocol for defining tDOA follows a systematic workflow that integrates multiple computational approaches with empirical data. A recent study demonstrated this methodology through a comprehensive analysis of 40 chemicals with diverse molecular targets, use categories, and mechanisms of action [1] [3]. The protocol consists of four distinct phases that progress from target identification to tDOA expansion.

The initial phase involves target identification and evaluation, where molecular targets for chemicals of interest are identified using multiple data sources, including EPA high-throughput in vitro data, ToxCast bioactivity data, structural data from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB), and existing chemical activity data from literature [1]. This multipronged approach ensures comprehensive target identification, capturing both primary and secondary molecular interactions.

The subsequent computational analysis phase applies SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN to the identified molecular targets. SeqAPASS analysis compares protein sequence similarities across species using the National Center for Biotechnology Information database to predict potential chemical susceptibility [2]. Concurrently, G2P-SCAN maps human gene inputs to biological pathways and evaluates their conservation across the seven model species [1]. This phase provides the foundational data for initial tDOA estimation.

The AOP development phase integrates the computational predictions with adverse outcome pathway construction. Researchers collect and structure various data types into AOP networks, then assess key event relationships using Bayesian network modeling approaches to quantify confidence in the proposed pathways [2]. This phase establishes the mechanistic links between molecular initiating events and adverse outcomes.

The final tDOA expansion phase uses the integrated computational results to extrapolate the biologically plausible tDOA beyond the initially studied species. The combined evidence from SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN supports expansion of the taxonomic domain of applicability to potentially include over 100 taxonomic groups [4] [2].

Case Study: Reproductive Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles

A compelling case study demonstrating the practical application of tDOA definition comes from research on silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) [2]. The study began with an existing AOP for AgNP-induced reproductive toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans (AOPwiki ID 207) and systematically expanded its tDOA through integrated computational approaches.

The research collected and analyzed 25 mechanism-based toxicity studies on AgNPs featuring different data types, including in vitro human cells, in vivo models, and molecular-to-individual level assessments [2]. The molecular initiating event was identified as NADPH oxidase and P38 MAPK activation, leading to reproductive failure [2]. The key events included oxidative stress, DNA damage, and impaired gametogenesis, culminating in reduced reproductive output as the adverse outcome.

Computational analysis using SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN enabled the extension of the biologically plausible tDOA from the initial model organisms (C. elegans, D. melanogaster, and in vitro human cells) to over 100 taxonomic groups, including fungi (98 species), birds (28 species), rodents, reptiles, and nematodes [2]. This expansion demonstrated how integrated computational approaches can significantly broaden the taxonomic applicability of AOPs while maintaining mechanistic credibility.

Table 2: tDOA Expansion for Silver Nanoparticle Reproductive Toxicity

| AOP Element | Initial Scope | Expanded Scope via Computational NAMs |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Initiating Event | NADPH oxidase and P38 MAPK activation in C. elegans [2] | Conserved across 100+ taxonomic groups [2] |

| Biological Pathways | Oxidative stress response in nematodes [2] | Pathway conservation across fungi, birds, rodents, reptiles [2] |

| Adverse Outcome | Reproductive failure in C. elegans [2] | Plausible across taxonomically diverse species [2] |

| Taxonomic Domain | C. elegans, D. melanogaster, in vitro human cells [2] | 100+ taxonomic groups including fungi (98), birds (28) [2] |

Comparative Analysis of tDOA Determination Approaches

Performance Metrics and Validation

The integration of SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN for tDOA determination represents a significant advancement over traditional approaches to cross-species extrapolation. Comparative analysis reveals distinct advantages in terms of predictive accuracy, taxonomic range, and mechanistic insight.

Traditional cross-species extrapolation in toxicology has primarily relied on the assumption that taxonomic relatedness confers similar chemical susceptibility [1]. This approach typically utilizes surrogate species to represent related taxonomic groups, with limited consideration of molecular mechanism conservation [3]. In contrast, the computational NAM approach focuses specifically on the conservation of molecular targets and biological pathways, providing a more mechanistic basis for extrapolation [1] [2].

Validation studies have demonstrated that the integrated computational approach successfully predicts known chemical susceptibilities while identifying previously unrecognized taxonomic domains. For instance, in the case of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPARα) interactions, the combined use of SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN provided enhanced weight of evidence to support cross-species susceptibility predictions beyond what either tool could accomplish independently [1]. Similarly, for estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit alpha (GABRA1) interactions, the pathway information from G2P-SCAN complemented the sequence similarity analysis from SeqAPASS, creating a more robust basis for tDOA definition [1].

Figure 2: Comparison of Traditional vs. Computational Approaches to tDOA

Quantitative Assessment of Method Performance

The performance of tDOA determination methods can be quantitatively assessed across multiple dimensions, including predictive accuracy, taxonomic coverage, mechanistic resolution, and utility for AOP development. The integrated computational approach demonstrates superior performance across these metrics compared to traditional methods.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of tDOA Determination Methods

| Performance Metric | Traditional Approach | Integrated Computational NAMs |

|---|---|---|

| Basis for Extrapolation | Taxonomic relatedness [1] | Protein sequence similarity & pathway conservation [1] [3] |

| Mechanistic Insight | Limited [3] | High - identifies specific molecular targets and pathways [1] [2] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Limited to phylogenetically related species [1] | Extensive - 100+ taxonomic groups possible [4] [2] |

| Validation Approach | Empirical testing in surrogate species [1] | Computational prediction with targeted verification [2] |

| AOP Utility | Limited to specific taxa [2] | Enables expansion of biologically plausible tDOA [4] [2] |

| Animal Use | High - requires multiple species testing [1] | Reduced - minimizes animal testing [4] [2] |

Essential Research Toolkit for tDOA Studies

Implementing tDOA definition studies requires access to specific computational tools, databases, and analytical resources. These components form the essential research toolkit that enables scientists to determine the taxonomic domain of applicability for adverse outcome pathways.

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for tDOA Definition

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in tDOA Studies | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeqAPASS | Computational tool | Predicts chemical susceptibility across species based on protein sequence similarity [1] [2] | Web-based: https://seqapass.epa.gov/seqapass/ [1] |

| G2P-SCAN | Computational tool | Estimates biological pathway conservation across species [1] [3] | R package [2] |

| NCBI Databases | Data resource | Provides protein sequence data for cross-species comparisons [2] | Publicly available |

| AOP-Wiki | Knowledge base | Structured AOP information including molecular initiating events and key events [2] | Publicly available |

| Reactome | Data resource | Pathway database used for conservation analysis [1] [3] | Publicly available |

| Comptox Chemicals Dashboard | Data resource | ToxCast bioactivity data for chemical target identification [1] | EPA resource: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/ [1] |

| RCSB Protein Data Bank | Data resource | Protein-ligand crystallization data for molecular target characterization [1] | https://www.rcsb.org/ [1] |

| Arylomycin B2 | Arylomycin B2, MF:C42H59N7O13, MW:870.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Melithiazole C | Melithiazole C, MF:C16H21NO5S, MW:339.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The strategic combination of these resources creates a powerful toolkit for defining tDOA without requiring extensive animal testing. The workflow typically begins with target identification using the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard and RCSB PDB, proceeds through sequence and pathway analysis with SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN, and culminates in AOP development with tDOA specification using the AOP-Wiki [1] [2]. This integrated approach represents the current state-of-the-art in mechanistic toxicology for cross-species extrapolation.

The precise definition of taxonomic domain of applicability (tDOA) represents a critical advancement in mechanistic toxicology and chemical safety assessment. By integrating computational approaches like SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN, researchers can now establish biologically plausible tDOAs based on conserved molecular targets and pathways rather than taxonomic proximity alone [1] [3] [2]. This paradigm shift enables more scientifically grounded cross-species extrapolations while supporting the reduction of animal testing through new approach methodologies [4] [2].

The case study on silver nanoparticle reproductive toxicity demonstrates how these computational tools can expand a well-characterized AOP from a few model species to over 100 taxonomic groups [2]. This expanded applicability domain significantly enhances the utility of AOPs for both ecological and human health risk assessment under the One Health framework [2]. As these computational methodologies continue to evolve and integrate with additional data sources, the precision and reliability of tDOA definition will further improve, strengthening the scientific basis for chemical safety decisions across the tree of life.

The Role of Structural and Functional Conservation in Defining Biological Plausibility

Defining the taxonomic domain of applicability (tDOA) is a critical step in Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) research, determining the range of species for which a documented pathway of toxicity is biologically plausible [5]. The foundational elements for establishing tDOA are structural conservation (the presence and preservation of biological entities like proteins and their functional domains) and functional conservation (the maintenance of equivalent biological roles across species) [5]. For researchers in toxicology and drug development, accurately defining the tDOA enables reliable cross-species extrapolation, which is vital for next-generation chemical safety assessments that seek to reduce reliance on whole-animal testing [3] [1].

This guide objectively compares the performance of two primary computational methodologies—the Sequence Alignment to Predict Across Species Susceptibility (SeqAPASS) tool and the combined use of SeqAPASS and the Genes to Pathways – Species Conservation Analysis (G2P-SCAN) tool. We present supporting experimental data, detailed protocols, and essential research tools to inform their application in AOP development.

Performance Comparison of Computational Methodologies

The strategic combination of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) can enhance the strengths and mitigate the limitations of individual tools [3] [1]. The following table summarizes the performance of SeqAPASS as a standalone tool versus its integration with G2P-SCAN.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Standalone and Combined Computational Approaches

| Feature | SeqAPASS (Standalone) | SeqAPASS + G2P-SCAN (Combined) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Predicts chemical susceptibility based on protein conservation [5] [1] | Enhances cross-species predictions by integrating protein conservation with pathway-level data [3] [1] |

| Taxonomic Scope | Broad; any species with available protein sequence data [5] [3] | Focused on 7 key model species (e.g., human, mouse, rat, zebrafish) [1] |

| Biological Scope | Protein-centric (MIEs & KEs) [5] | Pathway-centric (biological pathways & networks) [1] |

| Key Output | Evidence for structural conservation of molecular initiating events (MIEs) and key events (KEs) [5] | Consensus evidence for biological pathway conservation, expanding the biologically plausible tDOA of AOPs [1] |

| Reported Utility | Rapidly expands the potential tDOA for individual KEs in an AOP [5] | Provides a weight-of-evidence approach for predicting chemical susceptibility and pathway disruption [3] [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Methodology Application

Protocol 1: SeqAPASS Standalone Analysis for AOP Development

This protocol details the process of using the SeqAPASS tool to evaluate the structural conservation of proteins within an AOP framework, as demonstrated in a case study on an AOP linking nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) activation to colony death/failure in bees [5].

- Protein Identification: Identify all proteins involved in the AOP, specifically those associated with the Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) and subsequent Key Events (KEs). In the case study, nine proteins were identified [5].

- Data Retrieval and Input: For each query protein, obtain its primary amino acid sequence from a reference database (e.g., RefSeq, UniProt). Input the FASTA format sequence into the SeqAPASS web tool (v6.1+).

- Level 1 Analysis (Primary Sequence): Execute a Level 1 analysis to identify potential orthologs across the tree of life based on overall protein sequence similarity [5] [1].

- Level 2 Analysis (Functional Domains): Perform a Level 2 analysis to evaluate the conservation of known functional domains (e.g., from Pfam) within the identified orthologs [5].

- Level 3 Analysis (Critical Residues): Conduct a Level 3 analysis focusing on the conservation of specific amino acid residues known to be critical for protein-ligand interaction, protein-protein interaction, or protein function [5] [1].

- Data Interpretation and tDOA Definition: Synthesize the results from all three levels. A positive finding of conservation across these levels provides evidence of structural conservation, which can be used to define the biologically plausible tDOA for the MIE, KEs, and the overall AOP [5].

Protocol 2: Combined SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN Analysis

This protocol outlines the combined use of SeqAPASS and G2P-SCAN to generate consensus evidence for pathway-level conservation, as applied in a study of 40 chemicals with diverse modes of action [1].

- Chemical-Target Identification: Select chemicals of interest and identify their known molecular targets using a combination of high-throughput bioactivity data (e.g., ToxCast), structural data (RCSB PDB), and literature mining [1].

- SeqAPASS Evaluation: Subject the identified protein targets to the standard SeqAPASS workflow (Levels 1-3) to predict potential chemical susceptibility across a wide range of species [1].

- G2P-SCAN Pathway Mapping: Input the list of human genes encoding the molecular targets into the G2P-SCAN tool. The tool maps these genes to biological pathways (e.g., Reactome pathways) and estimates the conservation of these entire pathways across its seven predefined model species [1].

- AOP Network Integration: Compare the molecular and functional data from relevant AOPs with the mapped biological pathways to establish toxicological context [1].

- Weight-of-Evidence Synthesis: Integrate the findings from SeqAPASS (protein-level susceptibility) and G2P-SCAN (pathway-level conservation) to build a consensus on cross-species chemical susceptibility and to expand the biologically plausible tDOA for the relevant AOPs [1].

Workflow Visualization

Integrated Workflow for Defining AOP Taxonomic Applicability

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Databases for Conservation Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Primary Function | Application in tDOA Definition |

|---|---|---|

| SeqAPASS Tool | A hierarchical bioinformatics tool that compares protein sequence and structural similarity across species [5] [1]. | Provides lines of evidence for the structural conservation of MIEs and KEs, which is fundamental for establishing the biologically plausible tDOA of an AOP [5]. |

| G2P-SCAN Tool | A computational tool that maps human gene inputs to biological pathways and assesses their conservation across model species [1]. | Offers evidence for functional pathway conservation, supporting the extrapolation of entire AOP networks across taxa when combined with SeqAPASS [1]. |

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A database providing 3D structural data of proteins and their complexes with ligands [1]. | Critical for identifying amino acid residues involved in chemical binding (for SeqAPASS Level 3 analysis) and understanding molecular initiating events [1]. |

| RefChemDB | A curated database of high-throughput in vitro screening data [1]. | Used for the initial identification of molecular targets for chemicals, forming the starting point for cross-species extrapolation analyses [1]. |

| Reactome | An open-source, open-access, manually curated pathway database [1]. | Serves as a knowledgebase within G2P-SCAN for mapping gene targets to biologically relevant pathways whose conservation is then assessed [1]. |

In regulatory toxicology, the protection of untested species often relies on extrapolating data from a handful of tested species. The taxonomic domain of applicability (tDOA) of an Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) defines the range of species for which the described pathway is biologically plausible. For the majority of developed AOPs, the tDOA is typically narrowly defined, creating uncertainty in environmental and chemical risk assessment for the vast majority of species that lack empirical toxicity data [5] [6]. This article explores the critical importance of defining the tDOA, the methodologies employed, and its direct implications for making informed regulatory decisions to protect biodiversity.

The Critical Role of tDOA in the AOP Framework

An Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) is a structured representation that links a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE), through a series of intermediate Key Events (KEs), to an Adverse Outcome (AO) relevant for risk assessment [6] [7]. The AOP framework organizes existing knowledge to understand the causal mechanisms of toxicity.

The tDOA is an integral component of an AOP that outlines the species for which the pathway is considered valid. A precisely defined tDOA is crucial because:

- It supports the protection of untested species. Regulatory decisions must often consider a wide array of species for which no toxicity data exists. A well-substantiated tDOA provides a scientifically defensible basis to infer susceptibility across the taxonomic tree [5] [6].

- It enhances confidence in regulatory decision-making. Moving beyond assumptions of broad taxonomic coverage to evidence-based tDOA definitions reduces uncertainty, making ecological risk assessments more robust and reliable [6].

- It helps prioritize testing efforts. By identifying taxonomic groups where structural or functional conservation of a pathway is unlikely, resources can be directed towards testing the most relevant or susceptible species [5].

Defining the tDOA relies on evaluating two primary elements: structural conservation (is the biological entity, such as a protein, present and conserved?) and functional conservation (does the entity play the same role in different species?) [5] [6].

Methodologies for Defining the Taxonomic Domain of Applicability

Expanding the tDOA beyond the few species cited in an AOP's empirical studies requires a combination of bioinformatics and empirical evidence.

Bioinformatics Workhorse: The SeqAPASS Tool

A primary tool for evaluating structural conservation is the Sequence Alignment to Predict Across Species Susceptibility (SeqAPASS) tool [5] [6]. This publicly available bioinformatics tool uses a hierarchical approach to evaluate cross-species protein conservation, providing critical lines of evidence for the tDOA.

The tool operates through three tiers of analysis:

- Level 1: Compares primary amino acid sequence similarity to identify potential orthologs across species.

- Level 2: Evaluates the conservation of known functional domains within the protein sequence.

- Level 3: Assesses the conservation of specific amino acid residues critical for protein-ligand interactions, protein-protein interactions, or overall function [5] [6].

The workflow for integrating SeqAPASS into tDOA definition is systematic, as shown in the following diagram.

Case Study: nAChR Activation and Colony Death

A practical case study demonstrates this process. An AOP network links the activation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR—the MIE) to colony death/failure in honey bees (Apis mellifera), with neonicotinoid insecticides as prototypical stressors [5] [6]. While developed for honey bees, its relevance to over 20,000 other bee species was unknown.

Researchers used SeqAPASS to evaluate nine proteins involved in this AOP. The analysis provided evidence for the structural conservation of these proteins across various bee species, thereby expanding the biologically plausible tDOA of the AOP beyond A. mellifera to include other Apis and non-Apis bees [5]. This directly informs regulatory decisions regarding the potential risks of neonicotinoids to a broader range of pollinators.

Experimental Protocols & Data for tDOA Determination

The process of defining the tDOA combines computational and empirical approaches. The following protocol details the key steps, using the nAChR case study as a template.

Protocol 1: Defining tDOA using Bioinformatics and Empirical Integration

| Step | Description | Key Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. AOP Selection | Select a defined AOP with a narrowly defined tDOA. | Select AOP (e.g., AOP 89: nAChR activation leading to colony death). |

| 2. Protein Identification | Identify specific proteins critical to the MIE and KEs. | Compile a list of query proteins (e.g., nine proteins from the nAChR AOP). |

| 3. Bioinformatics Analysis | Evaluate structural conservation of proteins across taxa. | Input each query protein into the SeqAPASS tool. Execute Levels 1, 2, and 3 analyses. |

| 4. Ortholog List Generation | Generate a list of species with a high probability of possessing a functional ortholog. | Interpret SeqAPASS results to identify species where primary sequence, domains, and critical residues are conserved. |

| 5. Empirical Integration | Combine computational predictions with available toxicity data. | Overlay bioinformatics results with in vitro or in vivo toxicity data from the AOP-Wiki or literature to assess functional conservation. |

| 6. tDOA Definition | Formally define the biologically plausible tDOA. | Use the combined evidence to specify the species for which the KE, KER, and overall AOP are applicable. Document in AOP-Wiki. |

The data generated from these analyses can be synthesized into clear tables to support decision-making. The following table summarizes hypothetical, representative data for one of the nine proteins analyzed in the nAChR case study.

Table 1: Representative SeqAPASS Output and Toxicity Data for a Key Protein (e.g., nAChR subunit α1) in the AOP for nAChR Activation Leading to Colony Death [5] [6].

| Species | Level 1 (% Identity) | Level 2 (Domains Conserved) | Level 3 (Critical Residues) | Empirical Evidence (Ligand Binding EC50) | Plausible tDOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apis mellifera (Honey bee) | 100% | Yes (All) | Yes (All) | 1.0 µM (Reference) | Yes (Definitive) |

| Bombus terrestris (Bumble bee) | 95% | Yes (All) | Yes (All) | 1.2 µM | Yes (High Confidence) |

| Osmia bicornis (Red mason bee) | 90% | Yes (All) | Yes (4/5) | No data | Yes (Plausible) |

| Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit fly) | 80% | Yes (All) | Yes (3/5) | 5.5 µM | Likely |

| Danio rerio (Zebrafish) | 45% | Partial | No | No effect at 100 µM | No |

Successfully defining the tDOA of an AOP requires a suite of bioinformatics and data resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for tDOA Analysis.

| Tool / Resource | Function in tDOA Analysis |

|---|---|

| SeqAPASS Tool | A publicly accessible web-based platform that performs cross-species protein sequence and structural comparisons to predict potential chemical susceptibility [5] [6]. |

| AOP-Wiki (aopwiki.org) | The central repository for AOP knowledge, where information on the tDOA, along with supporting evidence for KEs and KERs, is documented and shared [5] [7]. |

| National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Protein Database | Provides the extensive, publicly available protein sequence data that tools like SeqAPASS rely on for their comparative analyses [5]. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) & DisGeNET | Bioinformatics resources used for overrepresentation analysis to map and classify AOPs based on their associated genes/proteins and diseases, helping to identify biological gaps and connections [7]. |

Implications for Regulatory Decision-Making

The formal definition of tDOA moves regulatory science away from assumption-based extrapolation and toward evidence-based prediction. This has profound implications:

- Justification for Read-Across: tDOA analysis provides a scientifically rigorous basis for read-across, where data from a tested species (e.g., Apis mellifera) is used to predict hazard in an untested species (e.g., Bombus terrestris) [5].

- Informing Testing Strategies: Regulatory testing frameworks can use tDOA information to select taxonomically appropriate surrogate species for testing when dealing with a diverse group of organisms of concern [6].

- Strengthening WoE Assessments: Evidence of structural and functional conservation significantly increases the weight of evidence (WoE) for the biological plausibility of an AOP in untested species, leading to more confident regulatory decisions [5] [6] [7].

The relationship between tDOA analysis and the broader AOP-based regulatory process is illustrated below.

Current efforts are focused on improving the FAIRness (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) of AOPs and their associated tDOA data [7]. Initiatives like the EU's Partnership for the Assessment of Risks from Chemicals (PARC) are actively using tDOA and AOP frameworks to identify and fill critical biological knowledge gaps, particularly in areas like immunotoxicity, endocrine disruption, and neurotoxicity [7].

In conclusion, defining the taxonomic domain of applicability is not a peripheral activity but a core component of modern, mechanism-based toxicology. By leveraging bioinformatics tools like SeqAPASS and integrating their outputs with empirical data, scientists can transform the tDOA from a narrow, species-limited description into a powerful, evidence-based tool. This evolution is fundamental for advancing regulatory decision-making and achieving the ultimate goal of proactively protecting all species, tested and untested, from environmental chemical stressors.

In the fields of toxicology and drug development, the concept of taxonomic coverage refers to the extent and reliability with which biological findings—particularly those related to chemical mechanisms and adverse outcomes—can be generalized across different species. The central challenge lies in the significant gap between the assumed breadth of these applications and the actual evidence supporting them. This discrepancy poses substantial risks for regulatory decision-making, drug safety profiling, and environmental risk assessment.

The advent of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)—including in silico models, in vitro assays, and pathway-based frameworks—aims to reduce animal testing while improving human and environmental relevance [8]. However, the adoption of these approaches in regulatory frameworks has been slow, due in part to uncertainties regarding their applicability across species and contexts [8]. Similarly, the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework provides a structured model connecting molecular initiating events to adverse outcomes, but its utility depends heavily on the accurate taxonomic characterization of each key event relationship [9] [10].

This guide examines the current limitations in evidence-based taxonomic coverage, comparing the performance of different methodological approaches and providing experimental data that highlights both the progress and persistent gaps in this critical research area.

The Theoretical Promise vs. Documented Limitations of Current Frameworks

The AOP Framework: Opportunities and Taxonomic Constraints

The Adverse Outcome Pathway framework represents a significant advancement in organizing mechanistic toxicological information. AOPs formally connect a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) to an Adverse Outcome (AO) through a series of biologically plausible Key Events (KEs) and Key Event Relationships (KERs) [9]. By 2017, over 200 AOPs had been established, demonstrating the framework's rapid adoption [9].

However, several limitations affect the taxonomic coverage of AOPs:

- Linearity Assumption: AOPs often assume a linear progression of events, while biological systems frequently exhibit pathway plasticity, compensatory mechanisms, and non-linear responses [9]

- Event Modifiers: The management of event modifiers (genetic, environmental, life-stage) and their variation across species remains challenging [9]

- Toxicokinetic-Toxicodynamic Separation: The separation of toxicodynamics from toxicokinetics including metabolism is difficult within the current AOP structure, limiting accurate cross-species extrapolation [9]

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): Confidence and Validation Gaps

NAMs encompass diverse technologies and approaches that replace, reduce, or refine animal testing, including in silico methods (QSARs), omics, read-across, in vitro assays, and organoids [8]. While offering significant potential, their adoption faces several taxonomic-related challenges:

- Scientific Confidence Frameworks: Establishing confidence in NAMs for cross-species extrapolation requires demonstrating relevance and reliability, defining applicability domains, and documenting strengths and limitations [8]

- Context of Use Limitations: Many NAMs have narrowly defined contexts of use, restricting their application across taxonomic boundaries [8]

- Validation Processes: Traditional validation approaches requiring ring trials are time- and resource-intensive, slowing the development of taxonomically-broad applications [8]

Table 1: Key Limitations Affecting Taxonomic Coverage in AOP and NAM Frameworks

| Limitation Category | Impact on Taxonomic Coverage | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Plasticity | Limits unidirectional assumptions in AOPs; complicates cross-species conservation | Multiple hit events in liver fibrosis [9] |

| Metabolic Variations | Restricts extrapolation of molecular initiating events across species | Species-specific metabolism of paracetamol and vinyl acetate [9] |

| Compensatory Mechanisms | Obscures adverse outcome pathways in resistant species | Tumor promotion mechanisms [9] |

| Domain Applicability | Constrains NAM use to specific taxonomic contexts | Limited wildlife species coverage for endocrine disruption assessment [8] |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches to Taxonomic Classification

Database-Dependent vs. Machine Learning Methods

In bioinformatics, taxonomic classification methods fall into two primary categories: database-based methods and machine learning approaches. A 2024 comparative study evaluated these methods using simulated datasets, with significant implications for their use in AOP development and validation [11].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Taxonomic Classification Methods [11]

| Method Type | Subcategory | Strengths | Limitations | Conditions for Optimal Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database-Based | Alignment-Based | High accuracy with comprehensive references | Computationally intensive for large datasets | Rich, comprehensive reference database available |

| Marker-Based | Efficient for conserved genes | Limited to known marker regions | Well-characterized marker genes exist | |

| k-mer-Based | Fast, universal application | Sensitive to sequence errors | High-quality sequencing data | |

| Machine Learning | Various Algorithms | Superior with sparse reference data | Performance limited by training data representativeness | Reference sequences sparse or lacking |

| Integrated Approaches | Multiple DB Methods | Enhanced classification accuracy | Increased computational complexity | Diverse database coverage available |

Key findings from the comparison include:

- Database methods excel in classification accuracy when supported by comprehensive reference databases but are constrained by database quality and scope [11]

- Machine learning methods offer advantages when reference sequences are sparse but their performance depends heavily on training data representativeness [11]

- Integration of multiple database methods enhances classification accuracy, suggesting hybrid approaches may offer the best taxonomic coverage [11]

Protein-Drug Interaction Mapping and Evolutionary Conservation

Understanding the evolutionary context of drug-target interactions provides crucial insights for taxonomic coverage. The DrugDomain database represents a significant advancement by mapping interactions between protein domains and drugs from DrugBank using the Evolutionary Classification of Protein Domains (ECOD) [12].

This resource highlights that:

- 72% of FDA-approved drugs in the last five years are small molecules, primarily targeting specific protein domains [12]

- Multi-domain binding sites present particular challenges for taxonomic extrapolation, as seen in human prostaglandin D-synthase and topoisomerase II beta [12]

- AlphaFold models have expanded coverage for human protein targets lacking experimental structures, improving taxonomic mapping capabilities [12] [13]

DrugDomain v2.0 now catalogs interactions with over 37,000 PDB ligands and 7,560 DrugBank molecules, providing an extensive resource for evaluating taxonomic conservation of drug-target interactions [13].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Taxonomic Coverage

Protocol 1: Evaluating Cross-Species Applicability of AOPs

Objective: To experimentally verify the taxonomic applicability of a proposed Adverse Outcome Pathway across multiple species.

Methodology:

Molecular Initiating Event Conservation Analysis

- Identify orthologs of the target protein across species of interest

- Use structural modeling (e.g., AlphaFold) to compare binding sites

- Assess binding affinity conservation using in vitro assays

Key Event Confirmation

- Develop species-specific in vitro models (primary cells or cell lines)

- Expose to graded concentrations of stressor

- Measure key event biomarkers using standardized assays

Adverse Outcome Verification

- Conduct in vivo studies in representative species (when ethically justified)

- Apply benchmark dose modeling to establish quantitative relationships

- Compare pathway sensitivity and potency across species

Data Interpretation: Quantitative consistency in MIEs and KEs across species supports broader taxonomic applicability, while significant variations indicate need for species-specific AOP development.

Protocol 2: Validation of NAMs for Cross-Species Extrapolation

Objective: To establish scientific confidence in New Approach Methodologies for taxonomic extrapolation, particularly for protected species.

Methodology:

Domain of Applicability Definition

- Map phylogenetic relationships of species of interest

- Identify relevant biological similarities and differences

- Establish acceptance criteria for extrapolation

Context of Use Evaluation

- Test reference chemicals with known cross-species effects

- Assess performance against existing in vivo data

- Evaluate under controlled experimental conditions

Uncertainty Characterization

- Identify knowledge gaps for specific taxonomic groups

- Quantify uncertainty using probabilistic methods

- Document limitations for regulatory consideration

Implementation: This protocol supports the use of fit-for-purpose collaborative case studies involving developers, users, and regulators, as encouraged for advancing NAM incorporation into standard practice [8].

Visualization of Taxonomic Coverage Assessment in AOP Development

AOP Taxonomic Coverage Assessment

This workflow outlines the process for evaluating the taxonomic coverage of Adverse Outcome Pathways, highlighting evidence collection across multiple biological levels and the subsequent determination of coverage strength.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Taxonomic Coverage Studies

| Resource | Primary Function | Application in Taxonomic Coverage | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| DrugDomain Database | Maps drug interactions to protein domains | Identifies evolutionary conservation of drug targets | http://drugdomain.cs.ucf.edu/ [12] [13] |

| AOP-Wiki | Repository for adverse outcome pathways | Assesses known AOPs and their taxonomic applicability | https://aopwiki.org/ [14] |

| ECOD Classification | Evolutionary protein domain classification | Provides framework for domain-level taxonomic comparisons | http://prodata.swmed.edu/ecod/ [12] |

| FAIR AOP Resources | Implements findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable AOP data | Supports standardized taxonomic annotations | https://www.epa.gov/risk/fair-aop-roadmap-2025 [14] |

| Integrated IATA | Integrated approaches to testing and assessment | Framework for combining multiple NAMs for taxonomic coverage | OECD IATA Guidance [10] |

The gap between assumed and evidence-based taxonomic coverage remains a significant challenge in toxicology and drug development. While frameworks like AOP and methodologies like NAMs offer promising approaches, their full potential is limited by insufficient characterization of taxonomic applicability.

Key strategies for addressing these limitations include:

- Enhanced Database Integration: Combining multiple database approaches improves taxonomic classification accuracy [11]

- Evolutionary Context Incorporation: Resources like DrugDomain provide crucial protein-domain interaction data for understanding taxonomic conservation [12] [13]

- FAIR Data Principles: Implementing findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable data practices for AOPs facilitates better taxonomic evaluation [14]

- Confidence Framework Application: Using Scientific Confidence Frameworks for NAM validation ensures appropriate taxonomic application [8]

As these approaches mature, the scientific community must prioritize transparent reporting of taxonomic limitations and continued development of frameworks that explicitly address—rather than assume—taxonomic coverage. This evidence-based approach is essential for reliable risk assessment, drug safety evaluation, and regulatory decision-making that adequately protects human health and the environment across species boundaries.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Approaches for Defining and Applying tDOA

The Sequence Alignment to Predict Across Species Susceptibility (SeqAPASS) tool, developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), represents a significant advancement in computational toxicology and ecological risk assessment. It addresses a fundamental challenge in toxicology: the impracticality of performing toxicity tests on every species potentially exposed to environmental contaminants [3]. SeqAPASS is a fast, freely available, online screening tool that enables researchers and regulators to extrapolate toxicity information from data-rich model organisms (e.g., humans, mice, rats, zebrafish) to thousands of other non-target species [15]. This capability is particularly vital for protecting biodiversity, assessing risks to pollinators and endangered species, and fulfilling the needs of modern chemical safety evaluations that seek to reduce reliance on animal testing [16] [17].

The tool's core premise is that a species' relative intrinsic susceptibility to a chemical can be predicted by evaluating the conservation of that chemical's known protein targets [16]. By leveraging publicly available protein sequence and structural information, SeqAPASS provides a scientifically grounded method to extrapolate molecular toxicity knowledge across the tree of life. This function is indispensable for defining the taxonomic domain of applicability (tDOA) for Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs), a critical element in the AOP framework that specifies the taxonomic space where an AOP is relevant [3]. As such, SeqAPASS has become an essential component in the toolbox of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working within the paradigm of 21st-century toxicology.

The Hierarchical Framework of SeqAPASS: A Multi-Tiered Approach for Cross-Species Extrapolation

SeqAPASS employs a hierarchical, multi-tiered approach that allows users to conduct analyses with varying degrees of specificity, from broad sequence comparisons to detailed structural evaluations. This framework is designed to capitalize on any existing knowledge about a chemical-protein interaction, making it flexible and adaptable to diverse research scenarios [16] [15].

Level 1: Primary Amino Acid Sequence Comparison

The initial analysis involves comparing the entire primary amino acid sequence of a query protein from a sensitive species against all species with available sequence data in public databases like the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [16]. This level provides a broad, screening-level assessment of protein conservation and potential chemical susceptibility across species.

Level 2: Functional Domain Comparison

The second level of analysis narrows the focus to the specific functional domains of the protein. This is crucial because chemicals often interact with specific protein regions rather than the entire sequence [16]. By evaluating domain conservation, SeqAPASS offers greater taxonomic resolution in its susceptibility predictions.

Level 3: Critical Amino Acid Residue Comparison

The third and most precise sequence-based analysis examines the conservation of individual amino acid residues known to be critical for chemical-protein binding or protein function [16] [17]. Even single amino acid differences can significantly alter species' susceptibility to chemicals, and this level accounts for such subtleties.

Level 4: Protein Structural Comparison (New in v8.0)

The latest version of SeqAPASS (v8.0) introduces a fourth level of analysis: protein structural comparison [18]. This advanced feature allows for the generation and alignment of protein structures across species, adding a powerful line of evidence for understanding conservation based on the principle that structure often determines function [17] [18]. It integrates tools like I-TASSER for protein structure prediction and iCn3D for visualization and structural superposition analyses [17] [18].

The following diagram illustrates the complete SeqAPASS workflow, from data input through the four hierarchical levels of analysis to the final output and interpretation.

Performance and Comparative Analysis of SeqAPASS

Performance Metrics and Tool Evolution

While direct, head-to-head performance comparisons between SeqAPASS and other specific bioinformatic tools for cross-species extrapolation are limited in the available literature, the continuous development and expanding feature set of SeqAPASS demonstrate its robust capabilities. The tool has evolved significantly since its initial release in 2016, with annual version updates incorporating new features based on user feedback and technological advancements [16]. The following table summarizes key performance-related features and their evolution.

Table 1: Evolution of SeqAPASS Tool Features and Capabilities

| SeqAPASS Version | Release Date | Key Performance and Feature Updates |

|---|---|---|

| v1.0 [16] | January 2016 | Initial public release with Level 1 (primary sequence) and Level 2 (functional domain) comparisons. |

| v3.0 [16] | March 2018 | Introduction of interactive data visualization capabilities and automatic Level 3 susceptibility prediction. |

| v4.0 [16] | October 2019 | Enhanced interoperability with ECOTOX Knowledgebase for empirical data comparison and summary reports. |

| v5.0 [16] | December 2020 | Customizable heat map visualization for Level 3 and a downloadable Decision Summary Report (.pdf). |

| v6.0 [16] | September 2021 | Widget for connecting SeqAPASS predictions to empirical toxicity data in the ECOTOX Knowledgebase. |

| v8.0 [18] | September 2024 | Introduction of Level 4 for protein structure generation/alignment and integration of iCn3D visualization. |

A key performance aspect of SeqAPASS is its robustness. The tool draws from the comprehensive NCBI protein database, which contains information on over 153 million proteins representing more than 95,000 organisms [15]. This vast data repository ensures that predictions are based on a wide biological space. Furthermore, the tool's design allows for rapid analysis; the protocol for assessing protein conservation can be completed in a short amount of time, generating customizable, publication-quality graphics and data summaries [16] [19].

Comparison with Alternative Approaches and Complementary Tools

SeqAPASS operates within a broader ecosystem of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). Its unique value becomes apparent when compared to, or used in combination with, other computational and empirical methods.

Comparison to Exome Capture Systems: Tools like NimbleGen's SeqCap EZ, Agilent's SureSelect, and Illumina's TruSeq and Nextera focus on enriching and sequencing the protein-coding regions of a genome for variant detection [20]. Unlike these technologies, which are wet-lab methods for data generation, SeqAPASS is a computational tool for data interpretation and extrapolation. It does not generate new sequence data but leverages existing public data to make predictions about chemical susceptibility. While exome capture is powerful for discovering genetic variation within a species, SeqAPASS specializes in comparing known protein targets across species.

Comparison to Chimeric RNA Prediction Tools: A 2021 benchmarking study evaluated 16 software tools for chimeric RNA prediction, including SOAPfuse, MapSplice, and FusionCatcher [21]. These tools are designed to identify fusion transcripts from RNA-Seq data, which is a distinct application from the cross-species extrapolation of chemical susceptibility performed by SeqAPASS. The domain of applicability for these tools is cancer genomics and transcriptome biology, whereas SeqAPASS is firmly situated in comparative toxicology and ecological risk assessment.

Synergy with G2P-SCAN and the AOP Framework: A powerful demonstration of SeqAPASS's utility is its integration with other computational NAMs. Research has shown that combining SeqAPASS with the Genes to Pathways – Species Conservation Analysis (G2P-SCAN) tool enhances predictions of chemical susceptibility across species [3]. While SeqAPASS evaluates protein conservation, G2P-SCAN infers biological pathway conservation. Used together, they provide multiple, complementary lines of evidence for the taxonomic domain of applicability of an AOP. This combination allows researchers to move from molecular target conservation (via SeqAPASS) to broader pathway conservation (via G2P-SCAN), creating a more comprehensive basis for extrapolation [3].

The following table summarizes the distinct roles and capabilities of SeqAPASS relative to other bioinformatic tools.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of SeqAPASS and Other Bioinformatics Tools

| Tool Category | Example Tools | Primary Purpose | Domain of Applicability | SeqAPASS Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Species Extrapolation | SeqAPASS, G2P-SCAN [3] | Predict chemical susceptibility across species based on protein/pathway conservation. | Ecological risk assessment, AOP tDOA. | Directly evaluates protein sequence/structure conservation for chemical targets. |

| Exome Capture Systems [20] | NimbleGen SeqCap EZ, Agilent SureSelect | Enrichment of exonic regions for deep sequencing. | Medical genetics, variant discovery in humans/model organisms. | A computational analysis tool, not a sequencing preparation method. |

| Chimeric RNA Prediction [21] | SOAPfuse, FusionCatcher, STAR-Fusion | Identify gene fusion transcripts from RNA-Seq data. | Cancer research, transcriptomics. | Focuses on protein-level conservation, not transcript-level fusion events. |

| Protein Structure Prediction | I-TASSER [17], AlphaFold | Predict 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences. | Structural biology, drug design. | SeqAPASS v8.0 integrates these tools (e.g., I-TASSER) into its Level 4 workflow. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Protocol for Running a SeqAPASS Analysis

The standard methodology for conducting a SeqAPASS analysis is detailed in published protocols [16] [19]. The process is designed to be accessible to both expert and non-expert users.

Getting Started and Protein Identification: Access the SeqAPASS tool through its official website (https://seqapass.epa.gov/seqapass/) using a Chrome browser and log in with a user account [16]. Prior to analysis, identify a protein of interest and a sensitive species through a literature review. The tool provides links to external resources like the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard and AOP-Wiki to aid in target identification [16].

Developing and Running the Query (Level 1): Initiate a Level 1 analysis by entering the query protein, typically using its NCBI protein accession number. The tool uses BLASTp algorithms to compare the primary amino acid sequence of the query protein against all species with available sequence data in the NCBI database [16]. The results are displayed as a taxonomic tree, with color-coding indicating the predicted susceptibility of different taxonomic groups.

Refining the Analysis (Levels 2 and 3): Based on the Level 1 results, the user can proceed to Level 2 by selecting specific functional domains to compare. For an even more refined analysis, Level 3 requires input on the specific amino acid residues critical for chemical binding. This information can be derived from crystallographic data or scientific literature, and the tool provides a "Reference Explorer" to help identify relevant sources [16].

Data Interpretation and Visualization: SeqAPASS provides multiple options for interpreting results, including interactive data visualizations, summary tables, and a comprehensive Decision Summary Report that synthesizes data across all analysis levels into a downloadable PDF [16]. The tool also allows for the creation of heat maps for Level 3 data, enabling rapid assessment of critical residue conservation [16].

Advanced Protocol: Integrating Structural Biology (Level 4)

With SeqAPASS v8.0, the experimental pipeline can be extended to include protein structural comparisons, adding a critical line of evidence for conservation [17] [18].

Sequence-Based Foundation: The process begins with a standard SeqAPASS evaluation (Levels 1-3) to identify orthologous protein sequences across species of interest [17].

Protein Structure Prediction: For species where a protein structure is not available in public databases, the pipeline uses advanced protein structure prediction tools like I-TASSER (Iterative Threading ASSEmbly Refinement). I-TASSER is a top-ranked algorithm that uses threading-based fold recognition and fragment-based assembly to generate accurate 3D protein models from amino acid sequences [17].

Structural Alignment and Comparison: The generated protein structures are then compared using structural alignment tools like TM-align. This algorithm measures structural similarity by calculating a Template Modeling Score (TM-score), which quantifies the conservation of protein folds across species, independent of sequence identity [17].

Visualization and Analysis: The final step involves visualizing the superimposed protein structures to assess conservation of the binding pocket geometry. SeqAPASS v8.0 integrates the iCn3D tool directly into its interface, allowing users to visualize and analyze the generated protein structures and their alignments [18].

The workflow for this advanced, multi-modal analysis is illustrated below.

Successful application of the SeqAPASS tool and its hierarchical framework relies on a suite of essential bioinformatic reagents and databases. The following table details key resources used in typical SeqAPASS experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for SeqAPASS Analyses

| Resource Name | Type | Function in SeqAPASS Workflow | Key Features/Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCBI Protein Database [15] | Database | Primary data source for protein sequences. | Contains over 153 million protein sequences from >95,000 organisms. |

| BLAST+ Executable [16] | Software Tool | Performs primary amino acid sequence alignments in Level 1 analysis. | Standard tool for comparing primary biological sequence information. |

| COBALT Executable [16] | Software Tool | Used for multiple sequence alignments in Level 2 and 3 analyses. | Tool for multiple protein sequence alignment that considers conservation. |

| I-TASSER [17] | Software Tool | Predicts 3D protein structures from sequences for Level 4 analysis. | Top-ranked algorithm for automated protein structure prediction. |

| TM-align [17] | Software Tool | Measures structural similarity of proteins for Level 4 analysis. | Algorithm for comparing protein structures; outputs TM-score. |

| iCn3D [18] | Software Tool | Visualizes protein structures and superpositions in SeqAPASS v8.0. | Integrated into SeqAPASS for interactive 3D structure visualization. |

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase [16] | Database | Provides empirical toxicity data for comparison with SeqAPASS predictions. | Curated database of chemical toxicity for aquatic and terrestrial life. |

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [16] | Database | Aids in identifying molecular targets for chemicals of interest. | EPA's database for chemistry, toxicity, and exposure data. |

SeqAPASS represents a paradigm shift in toxicological research, offering a robust, flexible, and hierarchical framework for addressing the complex challenge of cross-species extrapolation. Its multi-tiered approach—from primary sequence to protein structure—enables researchers to gather increasing levels of evidence to define the taxonomic domain of applicability for chemical interactions and Adverse Outcome Pathways. By leveraging vast public bioinformatic data and integrating with other NAMs like G2P-SCAN, SeqAPASS moves the field beyond reliance on traditional animal testing and toward a more predictive and efficient safety assessment paradigm.

The continuous evolution of the tool, culminating in the recent v8.0 release with its structural biology capabilities, demonstrates a commitment to incorporating scientific advances directly into the hands of researchers. For scientists and drug development professionals, mastering SeqAPASS is no longer just an advantage but a necessity for conducting state-of-the-art ecological risk assessments and for thoughtfully extending human-focused toxicological data to protect the broader environment.

The adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework provides a structured approach to organizing biological knowledge by delineating causal linkages between a molecular initiating event (MIE) and an adverse outcome (AO) relevant to risk assessment [6]. For this case study, we focus on AOP 89: nAChR Activation Leading to Colony Death/Failure, which was initially developed with specific emphasis on the honey bee (Apis mellifera) [6]. This AOP network emerged from concerns over the role of neonicotinoid insecticides in global bee population declines [22] [6]. The Taxonomic Domain of Applicability (tDOA) of an AOP defines the range of species for which the described pathway is biologically plausible [6]. Accurately defining the tDOA is critical for regulatory decision-making, particularly when extrapolating findings from tested species to protect untested ones. The core consideration for tDOA definition rests on evaluating the structural and functional conservation of Key Events (KEs) and Key Event Relationships (KERs) across taxa [6]. This case study demonstrates how bioinformatics tools, specifically the Sequence Alignment to Predict Across Species Susceptibility (SeqAPASS) tool, can be employed to systematically evaluate structural conservation and expand the tDOA for this critical AOP beyond A. mellifera to other bee species.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies for tDOA Analysis

Bioinformatics Workflow for Taxonomic Extrapolation

Defining the tDOA requires a methodical approach to evaluate the conservation of the AOP's components. The US Environmental Protection Agency's SeqAPASS tool offers a hierarchical framework for this purpose [6]. The workflow is structured into three progressive levels of evaluation, each providing distinct lines of evidence for structural conservation.

Level 1 Evaluation (Primary Sequence Comparison): This initial phase involves comparing the primary amino acid sequence of the molecular target (e.g., nAChR subunits) from a reference species (A. mellifera) against the protein sequences of other species. The analysis identifies putative orthologs—sequences that likely diverged from a common ancestor through speciation and are expected to maintain similar function. A high degree of sequence similarity at this level provides foundational evidence for the presence of the molecular target in other taxa [6].

Level 2 Evaluation (Functional Domain Conservation): This more refined analysis assesses the conservation of specific functional domains within the protein sequence. For nAChRs, this includes evaluating the preservation of agonist-binding domains critical for the interaction with neonicotinoid insecticides. Conservation of these domains across species strengthens the biological plausibility that the molecular initiating event (nAChR activation) can occur similarly [6].

Level 3 Evaluation (Critical Residue Conservation): The most granular level of analysis examines the conservation of individual amino acid residues known to be critical for protein-ligand interactions, protein-protein interactions, or overall protein function. For the nAChR, this involves assessing residues that form the orthosteric binding site where neonicotinoids act as agonists. The preservation of these specific residues across species provides strong evidence for comparable susceptibility to chemical perturbation [6].

Empirical Validation and Integration

While bioinformatics provides powerful evidence for structural conservation, defining the full tDOA also requires evidence of functional conservation. This is achieved by integrating SeqAPASS results with available empirical data from toxicological and physiological studies [6]. For bees, such data might include:

- In vitro receptor binding assays to confirm neonicotinoid affinity for nAChRs of different species.

- Sublethal behavioral assays measuring effects on learning, memory, or locomotion in response to exposure [23] [24].

- Whole-organism toxicity tests to establish dose-response relationships for key events such as impaired foraging or reduced colony growth.

The convergence of computational predictions and empirical observations provides a robust, weight-of-evidence basis for defining the tDOA for each KE, KER, and the AOP as a whole.

Comparative Analysis of AOP Component Conservation

The following tables summarize the evidence supporting the taxonomic domain of applicability for the key events and the overall AOP, based on the bioinformatics analysis and empirical evidence.

Table 1: Taxonomic Domain of Applicability for Key Events in AOP 89

| Key Event (KE) | Biological Level | Evidence for Structural Conservation (SeqAPASS) | Empirical Support for Functional Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| KE 1: nAChR Activation | Molecular/ Cellular | High conservation of nAChR subunit sequences, functional domains, and critical ligand-binding residues across Apis and non-Apis bees [6]. | In vitro binding studies and neurophysiological recordings confirm agonist action of neonicotinoids on nAChRs in multiple bee species [22] [24]. |

| KE 2: Altered Neural Function | Cellular/ Organ | Conservation of neural targets (e.g., mushroom bodies, central complex) and cholinergic signaling pathways across bee species [6]. | Impaired olfactory learning and memory demonstrated in laboratory assays for Bombus and Osmia exposed to neonicotinoids [24]. |

| KE 3: Impaired Foraging Behavior | Organism | Conservation of brain structures governing navigation and foraging behavior [6]. | Reduced foraging efficiency, disorientation, and impaired homing ability observed in field and semi-field studies with bumble bees and other wild bees [22] [24]. |

| KE 4: Reduced Colony Growth | Population | The social organization of a colony is a shared feature among eusocial bees like Apis and Bombus [22]. | Documented declines in brood production, food storage, and colony weight in neonicotinoid-exposed populations of bumble bees [22]. |

| AO: Colony Death/Collapse | Population | The adverse outcome is defined at the population level and is relevant to social bees that live in colonies [22] [6]. | Links between neonicotinoid exposure and increased colony failure rates or reduced queen production in multiple eusocial species [22] [24]. |

Table 2: Summary of tDOA for AOP 89 Across Major Bee Groups

| Bee Group | Example Genera | Confidence in AOP Applicability | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eusocial Bees | Apis (honey bees), Bombus (bumble bees) | High | Strong evidence for conservation of all KEs from molecular to population level. Empirical data from multiple species confirm functional links [6]. |

| Solitary Bees | Osmia (mason bees), Megachile (leafcutter bees) | Moderate | High confidence for early KEs (nAChR activation, neural impairment). Empirical data on foraging impairment exists. Confidence for colony-level AOs is lower due to different life history [6]. |

| Stingless Bees | Melipona, Trigona | Moderate (Theoretical) | Strong evidence for structural conservation of early KEs via SeqAPASS. Lacks extensive empirical toxicological data to confirm functional links to colony-level outcomes [6]. |

Visualization of the AOP and tDOA Analysis Workflow

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core AOP and the methodological workflow for tDOA analysis. The color palette and contrast adhere to the specified guidelines to ensure accessibility.

Diagram 1: AOP 89 - nAChR Activation to Colony Death

Diagram 2: Workflow for Defining tDOA using SeqAPASS

This table catalogues key computational, molecular, and bioinformatic resources essential for conducting tDOA analysis as described in this case study.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for tDOA Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in tDOA Analysis | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeqAPASS Tool | Bioinformatics Software | Evaluates protein sequence and structural similarity across species to infer potential chemical susceptibility [6]. | Determining conservation of nAChR subunits and critical ligand-binding residues between A. mellifera and non-Apis bees. |

| AOP-Wiki | Knowledge Repository | Central repository for developed AOPs, including KEs, KERs, and supporting evidence [6]. | Accessing the formal description of AOP 89 and its components as a baseline for tDOA expansion. |

| nAChR Subunit Proteins | Molecular Reagent | Used in in vitro competitive binding assays (e.g., radioligand binding) to confirm receptor-level interactions. | Validating the functional conservation of the Molecular Initiating Event by measuring neonicotinoid binding affinity to nAChRs from different bee species. |

| Curated Protein Databases | Data Resource | Provide the comprehensive, annotated protein sequence data required for cross-species comparisons in SeqAPASS [6]. | Sourcing protein sequences for nAChR subunits from a wide taxonomic range of Hymenoptera and other insects. |

| DAGitty | Causal Diagram Tool | A browser-based environment for creating, editing, and analyzing causal diagrams/directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) [25]. | Refining and visualizing the causal relationships within the AOP network and identifying potential confounding factors during empirical validation. |

Integrating Empirical Data with Computational Predictions for Robust tDOA Assessment

Time Difference of Arrival (TDOA) is a pivotal technique for passive localization in fields ranging from wireless networks to underwater navigation. This guide objectively compares the performance of contemporary TDOA methods, from compressed sensing to deep learning hybrids, by synthesizing experimental data on their accuracy under challenging line-of-sight (LoS) and non-line-of-sight (NLoS) conditions. Framed within a thesis on taxonomic domains for the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) research framework, this analysis provides drug development professionals and scientists with a structured comparison of methodological trade-offs in precision, data efficiency, and computational complexity.

Time Difference of Arrival (TDOA) is a passive localization technique that determines the position of a signal source by measuring the difference in the signal's arrival time at multiple, spatially separated receivers [26] [27]. Unlike Time of Arrival (ToA), which requires precise synchronization between the transmitter and all receivers, TDOA only requires synchronization among the receiving nodes, simplifying system design [28]. These time differences define hyperbolas, and the source's location is estimated at the intersection of multiple such hyperbolas, a process known as multilateration [27].

The core challenge in robust TDOA assessment lies in mitigating errors introduced by noise, multipath propagation, and particularly NLoS conditions, where the direct path between the source and receiver is blocked [28] [29]. NLoS conditions can cause significant positive biases in delay estimates, severely degrading localization accuracy. The methods discussed herein aim to address these challenges through a combination of empirical data processing and computational prediction.

Comparative Performance of TDOA Methods

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of modern TDOA methods, highlighting their respective approaches to handling NLoS conditions and their demonstrated accuracies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Contemporary TDOA Methods

| Method / Algorithm | Core Approach | Key Innovation | Test Environment | Reported Localization Accuracy | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIRCS [26] | Compressed Sensing | Inexact signal reconstruction preserving phase data | Simulation / General | High precision, minimal error at high compression ratios | High data compression, unbiased estimation |

| TDoA w/ NLoS Masking [28] | Channel Charting (CC) & Sensor Fusion | Masks NLoS measurements using CIR power distributions | Real 5G O-RAN Testbed | 2-4 meters (90% of cases) | Real-world robustness in mixed LoS/NLoS |

| Dual-Driven (AML TDoA) [29] | Data & Model-Driven Fusion | Transformer network for LoS ToA statistics | Urban Canyon Simulation | Approximates Cramer-Rao Lower Bound | Scalability, robust to varying BS combinations |

| CNN-BiGRU w/ Attention [30] | Deep Learning Hybrid | Attention on key TDOA/FDOA signal features | Underwater Simulation (20 dB SNR) | 2.58 meters (Position), 2.88 m/s (Velocity) | Superior in complex, dynamic environments (e.g., underwater) |

| Generalized Cross Correlation (GCC) [31] | Classical Signal Processing | Pre-filtering signals to sharpen correlation peak | Controlled / Simple Noise | Effective in high SNR, simple scenarios | Simplicity, well-established theory |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear basis for comparison, this section details the experimental methodologies and data analysis protocols for the key studies cited.

Enhanced Inexact Reconstruction Compressed Sensing (EIRCS)

- Objective: To achieve high-precision TDOA estimation while simultaneously compressing the volume of sampled data, overcoming challenges related to data acquisition, transmission, and storage [26].

- Protocol:

- Signal Model: Two sensors receive a common signal, denoted as ( x1(n) = s(n) + n1(n) ) and ( x2(n) = s(n - D) + n2(n) ), where ( D ) is the TDOA and ( n_i(n) ) is independent receiver noise [26].

- Compressed Sampling: The original signal ( \mathbf{s} ) is projected into a lower-dimensional space using a measurement matrix ( \mathbf{\Phi} ) to obtain linear measurements ( \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{\Phi s} ) [26].

- Inexact Reconstruction: The Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (OMP) algorithm is used to reconstruct a signal approximation from ( \mathbf{y} ) and the sensing matrix ( \mathbf{A} ). The focus is not on perfect signal reconstruction but on retaining the phase relationships critical for TDOA [26].

- TDOA Estimation: The cross-correlation of the inexactly reconstructed signals is computed, and the TDOA is estimated by finding the lag that maximizes this cross-correlation function [26].

- Data Analysis & Key Findings: The EIRCS method was validated as an unbiased estimation technique. Experimental results confirmed its ability to maintain high TDOA estimation precision even at high compression ratios, where the number of rows in the measurement matrix is significantly reduced [26].

Self-Supervised Channel Charting with NLoS Mitigation

- Objective: To enable global-scale, self-supervised user equipment (UE) localization in real 5G networks that is robust to NLoS conditions [28].

- Protocol:

- Data Collection: In a real-world O-RAN-based 5G testbed, Uplink Sounding Reference Signal (UL-SRS) Channel Impulse Response (CIR) data is collected alongside Time Difference of Arrival (TDoA) measurements and known Transmission Reception Point (TRP) locations. Ground truth positioning is provided by a centimeter-accurate Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) system [28].

- NLoS Identification: The empirical power distribution of the CIR data is analyzed to automatically identify and "mask" (i.e., exclude) measurements likely corrupted by NLoS propagation during model training and inference [28].

- Sensor Fusion Model Training: A Channel Charting (CC) model, a form of dimensionality reduction, is trained. The model uses a loss function that incorporates:

- CIR data to learn the local radio environment geometry.

- TDoA measurements and TRP locations to anchor the learned chart to a global coordinate system.

- Short-interval UE displacement measurements to improve trajectory continuity [28].

- Data Analysis & Key Findings: When benchmarked against RTK positioning, the proposed model achieved a localization accuracy of 2 to 4 meters in 90% of cases across a range of NLoS ratios, outperforming existing state-of-the-art semi-supervised and self-supervised CC approaches [28].

Dual-Driven AML TDoA with LoS Inference

- Objective: To combine the scalability of model-driven methods with the NLoS resilience of data-driven approaches for cooperative localization in mmWave MIMO networks [29].

- Protocol: