Cross-Species Pharmacokinetics: From Fundamental Principles to Model-Informed Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive examination of comparative pharmacokinetics across species, a critical discipline for translational medicine and drug development.

Cross-Species Pharmacokinetics: From Fundamental Principles to Model-Informed Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of comparative pharmacokinetics across species, a critical discipline for translational medicine and drug development. It explores the physiological and biochemical foundations of interspecies differences in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME). The content details advanced methodological approaches including pharmacokinetic modeling, simulation, and allometric scaling for predicting human pharmacokinetics from preclinical data. Practical applications and case studies illustrate how these principles optimize dosing regimens, troubleshoot developmental challenges, and validate findings across species. Finally, the article addresses regulatory considerations and comparative validation strategies to enhance the reliability of interspecies extrapolations, providing researchers and drug development professionals with an integrated framework for more efficient and predictive drug development.

The Physiological Basis of Interspecies Pharmacokinetic Variability

Key Physiological Determinants of ADME Processes Across Species

In drug development, understanding the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) of compounds is fundamental to predicting their pharmacokinetic (PK) behavior and ultimate efficacy. These ADME processes are not uniform across different biological systems; they are profoundly influenced by species-specific physiological determinants. For researchers and drug development professionals, a clear, comparative understanding of these determinants is crucial for selecting appropriate animal models, extrapolating human pharmacokinetics, and reducing late-stage drug failures. This guide provides an objective comparison of key physiological factors affecting ADME across common research species, supported by experimental data and standardized protocols. The content is framed within the broader context of comparative pharmacokinetics, enabling more informed decision-making in preclinical research.

Core Physiological Determinants of ADME

The physiological factors governing a drug's journey through an organism can be broadly categorized by the ADME phase they most significantly impact. The following sections and tables summarize the key determinants and their species-specific variations.

Determinants of Absorption and Distribution

Absorption describes the process of a drug entering the systemic circulation, while distribution involves its movement throughout the body. Key physiological parameters influencing these phases include body composition, gastrointestinal physiology, and cardiovascular function [1] [2].

Table 1: Species Comparison of Physiological Factors Affecting Drug Absorption and Distribution

| Physiological Factor | Human | Rat/Mouse | Dog | Non-Human Primate | Impact on ADME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Fat Percentage | Variable (≈18-25%) | Lower (≈10-15%) | Variable by breed | Generally Lower | Affects volume of distribution for lipophilic drugs [2] |

| Plasma Volume & Albumin | ~3L; ~35-50 g/L | Much lower | Species-specific | Species-specific | Influences drug binding and free fraction available [1] |

| Gastrointestinal Transit Time | ~4-8 hours (small intestine) | Much faster (~2-4h) | Similar to human | Most similar to human | Impacts absorption window for orally administered drugs [2] |

| Gastric pH (Fasted) | ~1.5-2.0 | Highly variable | ~1.5-2.5 (dog) | Similar to human | Affects dissolution and stability of ionizable drugs [2] |

| Cardiac Output | ~5 L/min | Proportionally higher | Proportionally higher | Species-specific | Influences rate of drug distribution to tissues |

Determinants of Metabolism and Excretion

Metabolism involves the biochemical modification of a drug, primarily in the liver, and excretion is the process of eliminating the drug and its metabolites from the body, often via the kidneys or bile. Key determinants include the expression and activity of metabolizing enzymes and renal function [3] [2].

Table 2: Species Comparison of Physiological Factors Affecting Drug Metabolism and Excretion

| Physiological Factor | Human | Rat/Mouse | Dog | Non-Human Primate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Profile | CYP3A4 (major), 2D6, 2C9 | Different isoforms (e.g., Cyp3a, 2d) | CYP2B11, 2C21, 3A12 | Most similar profile to human |

| Liver Blood Flow | ~1.5 L/min | Proportionally much higher | Proportionally higher | Species-specific |

| Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) | ~125 mL/min | Proportionally higher | Proportionally higher | Closest to human |

| Biliary Function | Standard | More active (rodents) | Species-specific | Similar to human |

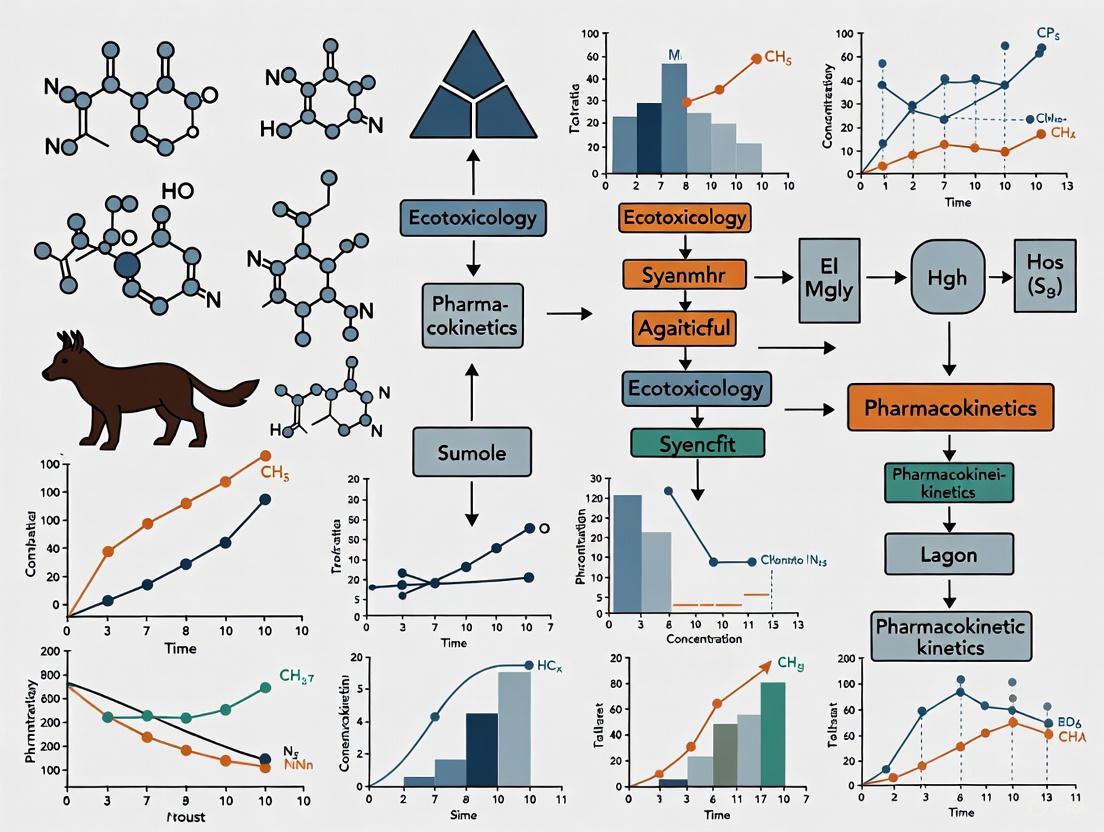

The relationships between these core physiological parameters and the resulting PK profile are complex. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow from a species' inherent physiology to its ADME characteristics.

Figure 1: The Logical Pathway from Physiology to Drug Efficacy. A species' physiological parameters directly determine the rates of ADME processes, which collectively define its pharmacokinetic profile and ultimately influence drug efficacy and toxicity.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing ADME Properties

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for generating reliable and comparable ADME data across species. The following section details key methodologies cited in the literature [2].

Lipophilicity Assessment (Log D)

Pharmacologic Question Addressed: "Will my parent compound be stored in lipid compartments or how well will it bind to a target protein?" Lipophilicity is a critical physicochemical property that influences solubility, absorption, membrane penetration, and distribution [2].

- Assay Design: The "shake-flask" method is the gold standard. Test articles are assayed in triplicate at one concentration (typically 10 µM) in a 1:1 mixture of n-octanol and aqueous buffer (pH 7.4). Positive (e.g., Testosterone) and negative (e.g., Tolbutamide) controls are included.

- Analysis: The concentration of the parent compound in each phase is measured using LC/MS/MS.

- Reporting: The result is reported as the Log D at pH 7.4, calculated as log([compound]~octanol~ / [compound]~buffer~).

- Compound Requirement: 1.0 - 2.0 mg.

Hepatic Microsome Stability

Pharmacologic Question Addressed: "How long will my parent compound remain circulating in plasma within the body?" This assay investigates the metabolic fate of compounds using subcellular liver fractions containing drug-metabolizing enzymes like cytochrome P450s (CYPs) [2].

- Assay Design: Test articles are incubated in triplicate with liver microsomes (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL from human, rat, or dog) at one concentration (typically 10 µM). Reactions are run with and without the cofactor NADPH to distinguish P450-mediated metabolism. Time points are taken at t = 0 and t = 60 minutes. A substrate with known activity (e.g., testosterone for CYP3A4) is used as a positive control.

- Analysis: LC/MS/MS is used to measure the remaining parent compound at each time point.

- Reporting: Data can be reported as a percentage of compound metabolized at a single time point or used to calculate intrinsic clearance and half-life with multiple time points.

- Compound Requirement: 1.0 - 2.0 mg.

Permeability Assays

Pharmacologic Question Addressed: "Will my compound be absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract?" Cell-based models like Caco-2 (human colon adenocarcinoma) are used to predict intestinal absorption.

- Assay Design: A monolayer of Caco-2 cells is grown on a permeable filter. The test compound is added to the donor compartment (apical for A->B transport, basolateral for B->A transport), and the amount appearing in the receiver compartment is measured over time.

- Analysis: LC/MS/MS is used to quantify the compound in both compartments. The apparent permeability (P~app~) is calculated.

- Reporting: Results are reported as P~app~ (A->B) for absorption potential and the efflux ratio (P~app~ (B->A) / P~app~ (A->B)) to identify substrates for efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein.

The workflow for a tiered ADME assessment strategy in early drug discovery is visualized below.

Figure 2: Tiered ADME Assessment Workflow. A two-tiered approach begins with rapid, cost-effective in vitro assays to screen compounds, followed by more resource-intensive in vivo pharmacokinetic studies for promising leads.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

A robust ADME screening program relies on specific reagents, tools, and databases. The following table details key solutions used in the field [4] [2].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADME Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic Microsomes | Subcellular liver fractions containing drug-metabolizing enzymes (CYPs, UGTs) for in vitro metabolism studies. | Assessing metabolic stability and identifying primary metabolic pathways in human, rat, dog, etc. [2] |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon cancer cell line that forms polarized monolayers, modeling the human intestinal barrier. | Predicting intestinal absorption and identifying efflux transporter substrates [2]. |

| Plasma/Serum | Sourced from various species for protein binding assays. | Determining the fraction of drug bound to plasma proteins, which influences free concentration and volume of distribution. |

| ADME Database | Specialized online databases (e.g., Fujitsu ADME Database) containing curated pharmacokinetic data. | Searching over 130,000 entries on metabolizing enzymes and transporters; comparing in vitro inhibition data with human clinical drug interaction data [4]. |

| CYP-Specific Probe Substrates | Compounds metabolized predominantly by a single cytochrome P450 enzyme (e.g., Testosterone for CYP3A4). | Serving as positive controls in enzyme activity and inhibition assays [2]. |

The physiological determinants of ADME processes vary significantly across species, presenting both a challenge and an opportunity for drug development researchers. A systematic, comparative understanding of factors such as body composition, organ function, and enzyme expression profiles is indispensable for selecting predictive animal models and for the accurate extrapolation of human pharmacokinetics. By employing standardized experimental protocols—such as microsomal stability and lipophilicity assays—and leveraging curated research tools and databases, scientists can generate robust, comparable data. This disciplined approach to comparative pharmacokinetics helps de-risk the drug development pipeline, ensuring that only the most viable candidate compounds, with ADME properties optimized for human therapeutic success, advance to clinical trials.

This guide objectively compares the anatomical and biochemical characteristics of digestive, metabolic, and excretory systems across species, providing supporting experimental data crucial for interspecies extrapolation in drug development.

Anatomical Comparisons of the Gastrointestinal Tract

The anatomical structure of the gastrointestinal (G.I.) tract directly influences drug dissolution, solubility, and transit times, causing significant variation in drug absorption from the oral route between humans and laboratory animals [5]. Key anatomical differences are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology in Common Laboratory Animals and Humans [5]

| Species | Stomach pH | Primary Absorption Site | Colon pH | Transit Time (Hours) | Relative Length of G.I. Tract | Bile Flow (mL/kg/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 1-2 (Fasted) | Small Intestine | 6-7 | 20-30 | Moderate | 1.4 - 5.3 |

| Mouse | 3-4 | Small Intestine | N/A | 5-11 | Short | 36.6 - 159 |

| Rat | 3-4 | Small Intestine | N/A | 12-24 | Moderate | 25.9 - 96.8 |

| Dog | 1-2 (Fasted) | Stomach, Small Intestine | 6-7 | 6-8 | Short | 4.5 - 19.3 |

| Monkey | 2-3 | Small Intestine | 6-7 | 15-24 | Moderate | 6.1 - 25.5 |

The G.I. tract is a continuous tube adapted for the sequential mechanical and enzymatic breakdown of food, with complexity increasing from simple organisms like sponges to more evolved mammals [6]. In higher animals, the tract features a two-opening system allowing continuous ingestion and excretion, significantly enhancing digestive efficiency [6]. Specialized structures, such as the small intestine, are critical for nutrient absorption, aided by features like villi that increase surface area [6].

The location and number of Peyer's patches, part of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, can be important in the absorption of large molecules and particulate matter, varying significantly across species [5]. The lipid/protein composition of the enterocyte membrane along the G.I. tract can also alter binding and passive, active, and carrier-mediated transport of drugs [5].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Drug Transit Time

Objective: To determine the transit time of an oral dosage form through the gastrointestinal tract in different animal species.

Methodology: [5]

- Administration: Animals are administered a radio-opaque marker or a stable, non-absorbable compound via oral gavage.

- Sampling: Feces are collected at predetermined time intervals post-administration.

- Analysis: The collected samples are analyzed for the presence of the marker. For radio-opaque markers, X-ray imaging can be used to track movement in real-time. For chemical markers, techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are employed.

- Data Analysis: The transit time is calculated as the time taken for the first appearance of the marker in the feces. Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation for each group (n≥5).

Biochemical and Metabolic Comparisons

Drug metabolism is the processing of a drug by the body into subsequent compounds, primarily to convert it into more water-soluble substances for renal or biliary clearance [7]. The liver is the principal site of this metabolism, which typically inactivates drugs, though some metabolites are pharmacologically active [8].

Key Metabolic Pathways

Metabolism often occurs in two phases [7] [8]:

- Phase I Reactions (Functionalization): Involve formation of a new or modified functional group via oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis. The most important enzyme system is cytochrome P-450 (CYP450).

- Phase II Reactions (Conjugation): Involve conjugation with an endogenous substance (e.g., glucuronic acid, sulfate, glycine) to make the drug more polar for excretion. Glucuronidation is the most common Phase II reaction.

Table 2: Key Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Their Activity Across Species [9] [8]

| Enzyme | Representative Substrate | Relative Activity in Common Species |

|---|---|---|

| CYP3A4 (Human) | Midazolam, Rivaroxaban | Human: High; Dog: Low; Rat: Moderate; Monkey: High |

| CYP2D6 (Human) | Tamoxifen, Bufuralol | Human: High (Polymorphic); Dog: Not significant; Rat: Moderate; Monkey: High |

| CYP2C9 (Human) | Warfarin, Phenytoin | Human: High; Dog: Low; Rat: Low; Monkey: Moderate |

| UGT (Glucuronidation) | SN-38 (Irinotecan metabolite) | Human: High; Cat: Deficient; Dog: Variable; Rat: High |

The following diagram illustrates the primary metabolic pathways and their localization within a hepatocyte.

Metabolism rates vary among individuals and species due to genetic factors, coexisting disorders, and drug interactions [8]. Most drugs follow first-order kinetics at therapeutic concentrations, but can saturate metabolic pathways and shift to zero-order kinetics at higher concentrations [8].

Experimental Protocol: Determining In Vitro Intrinsic Clearance

Objective: To estimate the intrinsic metabolic clearance (CL~int~) of a drug candidate using liver microsomes from different species. [9]

Methodology:

- Incubation: Liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL protein) are incubated with the test compound (1 µM) in a potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing NADPH (1 mM) as a cofactor. The reaction is carried out in a shaking water bath at 37°C.

- Sampling: Aliquots (50 µL) are taken from the incubation mixture at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes).

- Reaction Termination: The sampled aliquots are immediately added to a quenching solution (e.g., 100 µL of acetonitrile containing an internal standard) to stop the enzymatic reaction.

- Sample Analysis: Precipitated protein is removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant is analyzed using a validated LC-MS/MS method to determine the parent compound's concentration remaining at each time point.

- Data Analysis: The in vitro half-life (t~1/2~) and subsequently the CL~int~ are calculated from the slope of the natural logarithm of compound concentration versus time profile.

Advanced Modeling and Experimental Tools for Interspecies Extrapolation

Understanding physiological differences is critical for selecting the correct animal model to predict human bioavailability [5]. Two primary computational approaches are used for interspecies extrapolation.

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

PBPK models incorporate species-specific physiological parameters (e.g., organ sizes, blood flows, tissue composition) to simulate drug concentration-time profiles in plasma and tissues. A study on the carcinogen Dibenzo[def,p]chrysene (DBC) developed a PBPK model that accurately predicted its disposition in both mice and humans, outperforming traditional allometric scaling [10]. Similarly, a minimal PBPK model for betamethasone successfully captured its pharmacokinetic profile across five species using a conserved partition coefficient and species-specific clearance values [11]. These models are also valuable for identifying complex processes like intestinal loss of a drug, which can be challenging to distinguish from hepatic first-pass metabolism [12].

The workflow for developing and applying a PBPK model is shown below.

Allometric Scaling

Allometric scaling is a simpler empirical approach that uses power laws based on body weight to extrapolate pharmacokinetic parameters across species. A meta-analysis of betamethasone pharmacokinetics found that its apparent clearance correlated reasonably well with body weight (power coefficient of 1.0, R² = 0.93) [11]. However, PBPK modeling often provides more accurate predictions, as it mechanistically accounts for species differences in physiology and biochemistry [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Comparative DMPK Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Liver Microsomes (Human & Animal) | In vitro system for studying Phase I metabolism and determining intrinsic clearance. [9] |

| Recombinant CYP450 Enzymes | Used to identify which specific CYP enzyme is responsible for metabolizing a drug candidate. [9] |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line used as an in vitro model of the human intestinal mucosa to study drug permeability and transport. [12] |

| Specific Enzyme Inhibitors (e.g., Ketoconazole) | Used in reaction phenotyping studies to chemically inhibit specific CYP enzymes and elucidate metabolic pathways. [8] |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Provides a constant supply of NADPH, a crucial cofactor for CYP450-mediated oxidative reactions. [8] |

| Ultrasensitive Analytical Techniques (e.g., AMS) | Accelerator Mass Spectrometry allows for measuring pharmacokinetics at environmentally relevant, low (nanomolar) doses, critical for toxicokinetic studies. [10] |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | In vitro system that contains both Phase I and Phase II enzymes, providing a more complete model of hepatic metabolism than microsomes alone. [9] |

| Arisugacin C | Arisugacin C|Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor|For Research |

| Cimicifugic Acid D | Cimicifugic Acid D|CAS 219986-51-3|Research Chemical |

Peptide therapeutics represent a rapidly growing class of pharmaceuticals that bridge the gap between small molecule drugs and large biologics. Defined as polymers of less than 50 amino acids with a molecular weight under 10 kDa, therapeutic peptides offer superior specificity in targeting molecular interactions compared to traditional small molecules, while typically exhibiting lower immunogenicity and manufacturing costs than protein-based biologics [13] [14]. However, their development faces significant pharmacological challenges, particularly concerning their pharmacokinetic properties and tissue distribution patterns (organotropism). Unmodified peptides generally undergo extensive proteolytic cleavage, resulting in short plasma half-lives, and their low permeability and susceptibility to catabolic degradation severely limit oral bioavailability [13].

Organotropism—the preferential distribution of therapeutic agents to specific tissues and organs—is a critical determinant of peptide drug efficacy and safety. For peptide therapeutics, distribution processes are mainly driven by a combination of diffusion and, to a lesser degree, convective extravasation, with volumes of distribution frequently not exceeding the volume of extracellular body fluid [13]. Understanding and optimizing organotropism is especially crucial for developing peptides that target central nervous system disorders, as they must traverse formidable biological barriers like the blood-brain barrier (BBB). This case study examines the comparative pharmacokinetics and organotropism of two research peptides, HAEE and HASS, within the broader context of species-dependent absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties.

Comparative Pharmacokinetic Profiles of HAEE and HASS

HAEE Pharmacokinetics and Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration

HAEE (Acetyl-His-Ala-Glu-Glu-Amide) is a synthetic tetrapeptide analogue of the 35-38 region of the α4 subunit of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Its primary therapeutic mechanism involves specific binding to the 11-14 site of Aβ, thereby reducing cerebral amyloidogenesis in Alzheimer's disease models [15]. Pharmacokinetic studies conducted in multiple laboratory animal species following single intravenous bolus administration have provided crucial insights into HAEE's distribution profile.

Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters of HAEE [15]

- BBB Penetration: Pharmacokinetic data provide direct evidence that HAEE crosses the blood-brain barrier.

- Mechanism of Brain Uptake: Molecular modeling suggests a role for LRP1 (Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1) in receptor-mediated transcytosis of HAEE.

- Therapeutic Implication: The anti-amyloid effect of HAEE occurs due to its interaction with Aβ species directly in the brain parenchyma.

The ability of HAEE to cross the BBB represents a significant pharmacological advantage for CNS-targeting therapeutics, as this barrier prevents more than 98% of small molecules from entering the brain. The proposed LRP1-mediated transport mechanism is particularly significant, as this receptor is abundantly expressed at the BBB and plays a crucial role in transcytosing various ligands into the brain.

HASS Pharmacokinetics and Organotropism

Comprehensive pharmacokinetic data for the HASS peptide is currently limited in the available scientific literature. This significant gap in research presents challenges for direct comparison with HAEE's established organotropic profile. Future studies should prioritize characterizing HASS's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion patterns, with particular emphasis on its potential for CNS penetration compared to HAEE.

Comparative Pharmacokinetic Table

Table 1: Comparative Pharmacokinetic Parameters of HAEE and HASS Peptides

| Parameter | HAEE | HASS | Methodological Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration | Demonstrated in multiple animal models [15] | Insufficient data | Assessed via pharmacokinetic modeling and molecular docking |

| Proposed Transport Mechanism | LRP1-mediated transcytosis [15] | Insufficient data | Molecular modeling suggests receptor-mediated transport for HAEE |

| Primary Molecular Target | Aβ (11-14 site) [15] | Insufficient data | Surface plasmon resonance and binding assays confirm HAEE-Aβ interaction |

| Therapeutic Application | Alzheimer's disease (anti-amyloid) [15] | Insufficient data | Demonstrated in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's |

| Key Metabolic Challenges | Susceptibility to proteolytic degradation [13] | Insufficient data | Peptides generally vulnerable to ubiquitous proteases/peptidases |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Peptide Organotropism

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic and Biodistribution Studies

Animal Models and Dosing

- Species Selection: Studies should incorporate multiple species (typically rats and rabbits) to identify interspecies differences in peptide metabolism and distribution [16].

- Dosing Administration: Peptides are administered via single intravenous bolus injection into the caudal vein for precise pharmacokinetic profiling [17].

- Dose Selection: Doses should be calculated based on prior efficacy studies and radiolabeling requirements for accurate detection.

Sample Collection and Analysis

- Blood Sampling: Serial blood samples are collected at predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes post-injection) via indwelling catheters [17].

- Plasma Separation: Blood samples are immediately centrifuged (e.g., 5,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C) to obtain plasma.

- Tissue Collection: At terminal time points (e.g., 1 hour and 5 hours post-injection), target organs (brain, liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs, heart, muscle) are harvested, weighed, and homogenized [17].

- Radiolabel Detection: For radiolabeled peptides (e.g., tritium-labeled), tissue and plasma samples are analyzed using liquid scintillation counting to quantify peptide concentrations [17].

- Data Analysis: Non-compartmental analysis is performed to determine standard pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, Tmax, AUC, t1/2, Vd, Cl). Tissue distribution is expressed as volume of distribution (VD) by dividing radioactivity in each organ (dpm/g) by plasma radioactivity (dpm/μl) [17].

Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration Assessment

In Situ Cerebral Perfusion (ISCP)

- Surgical Preparation: Animals are anesthetized, and the common carotid arteries are exposed and cannulated.

- Perfusion Technique: Buffer containing the test peptide is perfused through the carotid artery at a constant flow rate for a predetermined period (e.g., 30-60 seconds) [17].

- Brain Collection: Immediately after perfusion, animals are decapitated, and the ipsilateral hemisphere is collected.

- Uptake Quantification: The brain uptake coefficient (µl gâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹) is calculated to quantify BBB permeability [17].

- Barrier Integrity Assessment: Inclusion of integrity markers (e.g., sucrose, inulin) confirms BBB remains intact during the experiment.

Molecular Modeling of Transport Mechanisms

- Receptor Docking Studies: Computational modeling predicts interactions between peptide candidates and BBB receptors (e.g., LRP1) [15].

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis: Systematic amino acid substitutions identify structural determinants of BBB penetration.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Peptide Organotropism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Radiolabeled Compounds | ³H-labeled peptides | Enable precise tracking and quantification of peptides in biological matrices via scintillation counting [17] |

| BBB Integrity Markers | ¹â´C-sucrose, ³H-inulin | Assess blood-brain barrier integrity during penetration studies [17] |

| Metabolic Stabilizers | Protease/peptidase inhibitors | Prevent ex vivo degradation of peptides during sample processing [13] |

| Molecular Modeling Tools | Docking software (AutoDock, Schrödinger) | Predict peptide-receptor interactions and transport mechanisms at biological barriers [15] |

| Chromatographic Systems | HPLC/UPLC with mass spectrometry | Separate and quantify peptides and their metabolites in complex biological samples [16] |

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating peptide organotropism and BBB penetration.

Species Differences in Peptide Pharmacokinetics

Interspecies variation significantly impacts the pharmacokinetic profiles of therapeutic peptides, creating challenges in translational research. Comparative studies in rats and rabbits reveal substantial differences in metabolic handling of peptide therapeutics, primarily attributed to variations in gastrointestinal esterases and peptidases [16]. These enzymatic differences directly influence organotropism by altering systemic exposure and tissue distribution patterns.

Key Species-Specific Metabolic Considerations [16]

- Rat Models: Exhibit intensive first-pass metabolism of ester-containing peptides via gastrointestinal esterases and peptidases, generating active metabolites but reducing parent compound bioavailability.

- Rabbit Models: Demonstrate lower enzymatic activity toward peptide substrates, resulting in prolonged plasma detection and potentially altered tissue distribution profiles.

- Structural Determinants: Ester derivatives (e.g., noopept, dilept) undergo more extensive hydrolysis than amide derivatives (e.g., GB-115), with the latter demonstrating greater metabolic stability across species.

- Translation Implications: Species selection critically influences pharmacokinetic parameters and must be carefully considered when extrapolating organotropism data to humans.

These interspecies differences extend beyond metabolism to include variations in hepatic and renal blood flow, protein binding, and tissue-specific uptake mechanisms—all factors that collectively determine organotropism. Understanding these differences is essential for designing appropriate preclinical studies and predicting human pharmacokinetics.

This comparative analysis highlights the critical importance of organotropism in developing effective peptide therapeutics, using HAEE as a model for CNS-targeting peptides with demonstrated blood-brain barrier penetration capabilities. The significant research gap regarding HASS pharmacokinetics underscores the need for systematic evaluation of its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties, particularly its potential for brain penetration relative to HAEE.

The translational value of organotropism studies depends heavily on careful consideration of species-specific metabolic differences and the application of rigorous experimental methodologies, including radiolabeled distribution studies and specialized BBB penetration assessments. Future research should prioritize structural-activity relationship studies to identify molecular determinants of desirable tissue distribution patterns, potentially enabling rational design of peptides with optimized organotropism for specific therapeutic applications.

As peptide therapeutics continue to expand into new disease areas, including metabolic disorders, oncology, and infectious diseases, understanding and controlling their tissue distribution will remain fundamental to developing safe and effective treatments. The methodologies and considerations outlined in this case study provide a framework for such investigations, emphasizing the integration of pharmacokinetic principles with therapeutic objectives.

Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms on Drug Metabolism and Disposition

Genetic polymorphisms significantly influence interindividual variability in drug metabolism and disposition, impacting both drug efficacy and safety. These variations in genes encoding drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporter proteins can alter pharmacokinetic parameters, leading to differential drug responses among patients and across species. Understanding these differences is critical in drug development and clinical practice, as it aids in predicting drug behavior, optimizing dosing regimens, and minimizing adverse drug reactions. This guide compares the impact of key genetic polymorphisms on drug metabolism and disposition, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Key Genetic Polymorphisms Affecting Drug Metabolism

Genetic polymorphisms in genes coding for cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and drug transporters are major contributors to variability in drug pharmacokinetics. The tables below summarize the effects of major polymorphisms.

Table 1: Major Cytochrome P450 Polymorphisms and Clinical Impact

| Enzyme | Key Substrates | Variant Alleles | Functional Effect | Clinical Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C9 | S-warfarin, phenytoin, fluvastatin [18] [19] | *2, *3 [19] | Reduced enzymatic activity [19] | Reduced drug clearance; increased risk of toxicity (e.g., bleeding with warfarin) [19] |

| CYP2C19 | Clopidogrel, proton pump inhibitors, voriconazole [20] | *2, *3 (Poor Metabolizers), *17 (Ultrarapid) [19] [20] | Deficient/Reduced or Increased activity [19] | Poor metabolizers: reduced activation of clopidogrel [20]. Ultrarapid metabolizers: therapeutic failure with omeprazole [19]. |

| CYP2D6 | Codeine, tamoxifen, tricyclic antidepressants [19] [20] | *3, *4, *5, *6 (Poor Metabolizers) [19] | Enzyme activity from deficient to ultrarapid [19] | Poor metabolizers: poor analgesic effect of codeine. Ultrarapid metabolizers: potential for toxicity [19]. |

| CYP3A5 | Tacrolimus [20] | *3 [20] | Reduced metabolism | Altered drug exposure requiring dose adjustment [20] |

Table 2: Key Drug Transporter Polymorphisms and Clinical Impact

| Transporter | Gene | Key Substrates | Key Polymorphism | Functional & Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OATP1B1 | SLCO1B1 | Statins (fluvastatin, simvastatin) [18] [20] | T521C (rs4149056) [18] | Reduced hepatic uptake; associated with increased systemic exposure and risk of statin-induced myopathy [18] [20] |

| P-glycoprotein | ABCB1 (MDR1) | Digoxin, cyclosporine, paclitaxel [21] | C3435T, G2677T/A [18] [21] | Altered drug absorption and distribution; influenced pharmacokinetics of drugs like indinavir and digoxin [21] |

| BCRP | ABCG2 | Rosuvastatin [20] | C421A [18] [20] | Reduced transport; increased plasma concentrations of substrates [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacogenetic Analysis

Clinical Study Design for Assessing Fluvastatin Pharmacogenetics

A typical clinical protocol to investigate the effect of genetic polymorphisms on drug pharmacokinetics involves a controlled crossover design [18].

- Study Population: Recruit healthy subjects (e.g., n=24), with health status confirmed by medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests. Obtain written informed consent and ethical approval [18].

- Study Design: Open-label, randomized, two-period, two-treatment crossover study. For example:

- Treatment A: Fluvastatin 40 mg immediate-release (IR) capsule twice daily for 7 days.

- Treatment B: Fluvastatin 80 mg extended-release (ER) tablet once daily for 7 days.

- Include a washout period (e.g., one week) between treatment periods [18].

- Blood Sampling: Collect serial blood samples (e.g., 3.5 ml) at multiple time points following drug administration on Day 1 (single dose) and Day 7 (steady state). For an ER formulation, samples may be taken at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, and 24 hours. For a twice-daily IR formulation, sampling is more frequent around both doses [18].

- Sample Processing: Centrifuge blood samples to separate serum. Store serum samples at -70°C until analysis [18].

- Genotyping: Genotype participants for relevant polymorphisms (e.g., SLCO1B1 T521C, CYP2C93, CYP3A53, ABCB1, ABCG2) using validated methods [18].

- Data Analysis:

- Use HPLC-MS/MS to determine serum drug concentrations [18].

- Calculate pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., AUC~0-24~, C~max~, T~max~, t~1/2~).

- Employ statistical models (e.g., ANOVA, nonlinear mixed-effects models) to analyze the effect of genotype on PK parameters, accounting for factors like formulation and dosing day [18] [21].

In Vitro Transporter Kinetics Assay

In vitro studies help mechanistically confirm clinical findings, such as the impact of the SLCO1B1 T521C polymorphism on fluvastatin uptake [18].

- Cell Culture: Maintain engineered cell lines, such as HEK293 cells stably transfected with reference (SLCO1B1 521TT) or variant (SLCO1B1 521CC) transporter [18].

- Uptake Experiment:

- Grow cells to confluence in appropriate media (e.g., DMEM with FBS and antibiotics).

- Incubate cells with varying concentrations of the drug of interest (e.g., fluvastatin from <1 µmol/L to >1 µmol/L) for a defined period.

- Terminate the uptake process by washing cells with cold buffer.

- Lyse cells and analyze drug concentration inside the cells using a sensitive method like LC-MS/MS.

- Data Analysis:

- Determine kinetic parameters (K~m~, V~max~) for the transporter in both reference and variant cell lines.

- Compare uptake velocities at different substrate concentrations to understand how polymorphism affects function, especially at low vs. high drug concentrations [18].

Visualization of Pharmacogenetic Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and relationships between genetic polymorphisms, their functional consequences, and the resulting clinical outcomes.

Figure 1: Pathway from genetic polymorphism to clinical outcome, showing how variants in genes like CYP450s or transporters alter function, leading to changes in pharmacokinetics (PK) and ultimately impacting patient response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Pharmacogenetic Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Transfected Cell Models | In vitro study of transporter function and kinetics. | HEK293 or CHO cells stably expressing variant (e.g., SLCO1B1 521CC) or reference transporters [18]. |

| Clinical DNA Samples | Genotyping and correlation with pharmacokinetic data. | DNA extracted from participants in clinical trials, with informed consent for pharmacogenetic analysis [18]. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Sensitive and specific quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices (serum, cell lysates). | HPLC system (e.g., Waters Xterra MS C18 column) coupled to a mass spectrometer (e.g., API4000) [18]. |

| Pharmacogenetic Databases | Curated evidence for gene-drug relationships and clinical implementation guidelines. | PharmGKB, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines [22] [23] [20]. |

| Statistical Software | Analysis of genotype-PK relationships using population PK modeling or hypothesis testing. | NONMEM, R, or other software for ANOVA on EBEs or likelihood ratio tests in mixed-effects models [21]. |

| Memnobotrin A | Memnobotrin A, MF:C25H33NO5, MW:427.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fudecalone | Fudecalone | Research-grade Fudecalone, a synthetic drimane terpenoid with anticoccidial activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Cross-Species Comparisons in Pharmacokinetics

Understanding species differences is fundamental to extrapolating animal data to humans in drug development. While the basic structure of biomembranes and absorption processes are similar across mammals, significant differences exist in metabolism and excretion [24] [25].

- Absorption: The intrinsic absorption of a drug across the gastrointestinal epithelium is generally similar among species. However, factors like gastric pH, GI tract anatomy (ruminant vs. non-ruminant), and first-pass metabolism can vary considerably, leading to species differences in overall oral bioavailability [24] [25] [26].

- Metabolism: This is a major source of interspecies variation. Cytochrome P450 enzymes and other metabolizing systems have different expression levels, substrate specificities, and catalytic activities across species [24] [25] [26]. For example, the high rate of oxidative metabolism in mice can make them poor models for chronic human toxicity studies [26].

- Elimination: Renal excretion can be predicted with relative success using allometric scaling based on glomerular filtration rates. In contrast, hepatic clearance limited by metabolism is less predictable due to the biochemical variability of drug-metabolizing enzymes [24].

Cardiovascular and Body Composition Differences and Their PK Implications

In the field of comparative pharmacokinetics (PK), understanding the interplay between cardiovascular physiology, body composition, and drug disposition is paramount for translating findings from nonclinical models to human patients. Significant differences in body structure and cardiovascular function between species, and between individuals within a species, introduce substantial variability in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of pharmaceutical compounds [27]. The rising prevalence of polypharmacy further amplifies this challenge, increasing the risk of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) that can alter drug exposure and compromise therapeutic efficacy or safety [28]. This guide objectively compares the influence of cardiovascular and body composition factors on PK parameters across research models, providing a structured overview of key experimental data and methodologies essential for drug development professionals.

Body Composition Parameters and Their Pharmacokinetic Relevance

Body composition—the relative proportions of fat, muscle, bone, and water in the body—profoundly influences drug pharmacokinetics. Key parameters provide predictive value for cardiometabolic risk and drug disposition.

Table 1: Body Composition Assessment Methods and PK Implications

| Assessment Method | Measured Parameters | Pharmacokinetic Implications | Key Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waist Circumference [29] | Abdominal adiposity | Altered volume of distribution ((V_d)) for lipophilic drugs; modified drug clearance. | Recommended thresholds: ≤37 inches (men), ≤32 inches (women). Exceeding these indicates higher cardiometabolic risk [29]. |

| Waist-to-Hip Ratio [29] | Fat distribution pattern ("apple" vs. "pear" shape) | Influences drug distribution and metabolism; apple shape (higher ratio) linked to greater PK variability. | A ratio where waist > hips indicates higher risk for weight-related health issues and potential alterations in drug response [29]. |

| Body Fat Percentage (BFP) [29] | Proportion of total mass as fat | Higher BFP increases (V_d) and half-life for lipophilic drugs; can delay onset and prolong duration of action [30]. | Healthy ranges: 8-19% (men), 21-33% (women). Higher percentages correlate with cardiovascular disease risk [29]. |

| AI-MRI Analysis [31] | Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT), Skeletal Muscle (SM) proportion, Skeletal Muscle Fat Fraction (SMFF) | VAT and SMFF are independent predictors of metabolic dysfunction, potentially affecting hepatic drug metabolism and systemic clearance. | High VAT and SMFF associated with increased diabetes (aHR: 2.16 women, 1.84 men) and major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) risk after adjusting for BMI [31]. |

| Bio-impedance Analysis (BIA) [32] | Fat-free mass (FFM), Fat mass (FM), Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) | FFM and BMR are key determinants of drug clearance; lower FFM may correlate with reduced metabolic capacity. | Studies show body composition (BMI, FFM, BMR) significantly influences cardiorespiratory fitness, an indirect marker of overall metabolic health and drug clearance capacity [32]. |

Cardiovascular and Gender Differences in Drug Response

Significant gender-related differences in cardiovascular physiology and pharmacology exist, driven by variations in body composition, hormone levels, and metabolizing enzymes.

Table 2: Gender Differences in Cardiovascular Drug Pharmacokinetics and Effects

| Drug Class | Documented Gender Difference | Postulated Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Beta-Blockers (e.g., Metoprolol, Propranolol) [30] | Higher plasma levels in women; slower clearance; greater reduction in exercise heart rate and systolic blood pressure. | Slower clearance and lower volume of distribution in women, potentially due to body composition differences. |

| Statins [30] | Generally higher plasma concentrations in women. | Body size and composition differences; women have higher CYP3A4 concentrations, affecting metabolism of lipophilic statins. |

| Anticoagulants (Warfarin) [30] | Women typically require lower doses for therapeutic INR. | Influenced by protein binding and exogenous sex hormones. |

| Digoxin [30] | Associated with increased risk of death in women with heart failure. | Not fully elucidated; may be related to dosing relative to body size rather than intrinsic PK differences. |

| Calcium Channel Blockers (e.g., Verapamil) [30] | Increased clearance observed in women. | Not fully specified; potentially due to gender-specific metabolic pathways. |

Underlying these pharmacological differences are fundamental physiological disparities. Females generally have higher body fat percentages, influencing the distribution of lipophilic drugs [30]. They also exhibit distinct hemodynamic regulation, including lower vascular resistance and a blunted sympathetic response during physical exertion compared to males [33]. Furthermore, hepatic drug clearance is often lower in women, impacting the metabolism of numerous cardiovascular medications [30]. These factors collectively contribute to the higher incidence of certain adverse drug reactions, such as drug-induced torsades de pointes, in women [30].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Body Composition and Cardiovascular Function

AI-Based Body Composition Analysis from MRI

The automated analysis of body composition from whole-body MRI scans represents a advanced methodological approach.

- Objective: To derive accurate 3D measurements of body composition compartments (VAT, SAT, SM, SMFF) and assess their association with cardiometabolic outcomes [31].

- Procedure:

- Subject Preparation: Participants undergo whole-body MRI scanning according to standard institutional protocols.

- Image Acquisition: High-resolution MRI images are obtained.

- AI Analysis: An artificial intelligence tool is applied to the MRI DICOM data to automatically segment and quantify different tissue types.

- Data Calculation: The relative proportions of subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), visceral adipose tissue (VAT), skeletal muscle (SM), and skeletal muscle fat fraction (SMFF) are calculated.

- Statistical Analysis: Associations between these composition measures and incident diabetes or major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) are evaluated using multivariate Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for confounders like age, smoking, and hypertension [31].

- Key Outputs: Hazard ratios (aHR) for disease outcomes per standard deviation increase in body composition metric; quantification of the proportion of the population in high-risk categories (e.g., top 5th percentile for VAT) [31].

Cardiorespiratory Fitness (CRF) Assessment via Balke Treadmill Test

The Balke treadmill protocol is a standardized method to assess maximal oxygen uptake (VOâ‚‚ max), a gold-standard measure of cardiorespiratory fitness.

- Objective: To determine maximal oxygen uptake (VOâ‚‚ max) as a primary indicator of cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular health [32].

- Procedure:

- Subject Preparation: Participants are asked to abstain from eating or drinking for 4-5 hours prior to testing. Pre-test anthropometric measurements (height, weight) and body composition (via bio-impedance analyzer) are taken [32].

- Baseline Measurements: Resting heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), and respiratory rate (RR) are recorded.

- Exercise Protocol: The participant walks on a treadmill at a constant speed with incremental grade increases (typically 1% per minute) until volitional exhaustion.

- Monitoring: HR, BP, and RR are monitored throughout the test. The test is terminated if the participant experiences excessive fatigue or distress.

- Calculation: VO₂ max is calculated using the formula: VO₂ max = 1.38 × T + 5.22, where "T" is the total test time in minutes and fractions of a minute [32].

- Key Outputs: VOâ‚‚ max value (mL/kg/min); correlation data between VOâ‚‚ max and body composition parameters like BMI and body fat percentage [32].

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) Intervention Study

This protocol examines individual variability in response to exercise, linking changes in body composition to cardiovascular and cardiorespiratory adaptations.

- Objective: To investigate cardiovascular and cardiorespiratory adaptations to exercise in individuals showing different levels of responsiveness to changes in body fat percentage (BFP) [34].

- Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment: Adolescents or adults are recruited and randomly assigned to experimental or control groups.

- Pre-intervention Testing: Baseline measurements of BFP (using a validated analyzer like InBody230), resting BP, and CRF (e.g., VOâ‚‚ max) are collected.

- Intervention: The experimental group undergoes a structured HIIT program (e.g., 10 weeks of school-based HIIT during physical education lessons). The control group continues with standard activities.

- Post-intervention Testing: All baseline measurements are repeated after the intervention period.

- Data Analysis: Participants are classified as Responders (RsBFP) or Non-Responders (NRsBFP) based on their change in BFP. Pre- and post-intervention BP and CRF are compared between these groups to determine if body fat changes correlate with cardiovascular benefits [34].

- Key Outputs: Mean change in BFP, systolic BP, and CRF in RsBFP vs. NRsBFP; statistical analysis of interaction effects (e.g., via ANOVA) [34].

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Body Composition Impact on Pharmacokinetics

- Title: Body Composition Impact on PK

Experimental Body Composition Workflow

- Title: Experimental Body Composition Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Body Composition and PK Research

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Example | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-impedance Analyzer (BIA) [32] | Measures body composition (FFM, FM, BFP, BMR) via electrical impedance. | Prospective cross-sectional studies linking body composition to cardiorespiratory fitness (VOâ‚‚ max) [32]. | Non-invasive; provides rapid estimates of multiple body composition parameters. |

| Whole-Body MRI with AI Software [31] | Provides precise 3D volumetric quantification of body compartments (VAT, SAT, SM). | Large-scale cohort studies to establish associations between specific fat/muscle deposits and cardiometabolic risk [31]. | High accuracy; enables opportunistic assessment from routine clinical images; automated analysis. |

| Body Composition Analyzer (e.g., InBody230) [34] | Directly measures body weight, BFP, fat mass, and fat-free mass. | Monitoring changes in body fat percentage in response to exercise interventions (e.g., HIIT studies) [34]. | High reliability (ICC ≥ 0.98); essential for classifying treatment responders vs. non-responders. |

| Automated Blood Pressure Monitor [34] | Measures resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure. | Assessing cardiovascular adaptations and safety endpoints in intervention studies and clinical trials [34]. | Standardized, non-invasive cardiovascular assessment. |

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLMs) [28] | In vitro system containing human CYP enzymes for drug metabolism studies. | Reaction phenotyping to identify enzymes responsible for drug metabolism and assess DDI potential [28]. | Critical for predicting metabolic clearance and enzyme-mediated DDIs in early drug development. |

| Recombinant Human Enzyme (RHE) Systems [28] | Engineered cell systems expressing specific human metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYPs). | Used alongside HLMs to identify which specific enzyme metabolizes a drug candidate [28]. | Allows for isolated study of a single enzyme's activity, clarifying metabolic pathways. |

| Andrastin B | Andrastin B, MF:C28H40O7, MW:488.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Goxalapladib | Goxalapladib, CAS:412950-27-7, MF:C40H39F5N4O3, MW:718.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Modeling & Simulation Approaches for Interspecies Extrapolation

Population PK (Pop-PK) and Physiologically-Based PK (PBPK) Modeling Fundamentals

In modern drug development, pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling serves as a critical tool for predicting how drugs behave in the body. Among the most advanced approaches are Population PK (Pop-PK) and Physiologically-Based PK (PBPK) modeling, which represent fundamentally different yet complementary methodologies [35]. Pop-PK modeling employs a "top-down" empiric approach, analyzing observed clinical concentration data to identify and quantify sources of variability in drug exposure [35] [36]. In contrast, PBPK modeling utilizes a "bottom-up" mechanistic framework, constructing mathematical representations of the body as a network of physiologically defined compartments to predict drug disposition based on drug properties and human biology [37] [38]. These approaches differ in their epistemological foundations, data requirements, and applications across the drug development continuum, yet both aim to optimize dosing strategies and predict drug behavior in diverse populations [36].

Core Principles and Methodological Foundations

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

PBPK models represent the body as a network of anatomically realistic compartments corresponding to specific organs and tissues, interconnected by the circulatory system [37] [38]. Each compartment is defined by physiological parameters including tissue volume, blood flow rate, and tissue composition [38]. Drug movement through this system is described using mass-balance differential equations that account for drug-specific properties and physiological processes [37] [38].

The fundamental equation governing drug distribution in a non-eliminating tissue compartment is:

V_T × dC_T/dt = Q_T × C_A - Q_T × C_VT [38]

Where:

V_T= Tissue volumeC_T= Drug concentration in the tissueQ_T= Blood flow to the tissueC_A= Drug concentration in arterial bloodC_VT= Drug concentration in venous blood leaving the tissue

For eliminating tissues (e.g., liver), an additional term representing metabolic clearance (CL_int × C_VuT) is incorporated into the equation [38]. PBPK models separate system-dependent parameters (species-specific physiology) from drug-dependent parameters (compound-specific properties), enabling predictions across different populations and species [39].

Population Pharmacokinetic (Pop-PK) Modeling

Pop-PK modeling employs nonlinear mixed-effects models to analyze sparse PK data from study populations, identifying and quantifying sources of variability in drug exposure [35] [40]. Unlike PBPK's physiological compartments, Pop-PK compartments are typically empirical without direct physiological correspondence—described as "central" and "peripheral" rather than representing specific organs [35].

The Pop-PK framework estimates:

- Fixed effects: Typical population parameter values (e.g., clearance, volume of distribution)

- Random effects: Inter-individual variability and residual unexplained variability

- Covariate effects: Relationships between patient factors (e.g., age, renal function) and PK parameters [35]

Pop-PK models are developed iteratively, starting with simple structural models and progressively adding complexity to account for covariate relationships that are both statistically significant and biologically plausible [35].

Comparative Analysis: PBPK vs. Pop-PK

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of PBPK and Pop-PK modeling approaches

| Characteristic | PBPK Modeling | Pop-PK Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Bottom-up, mechanistic | Top-down, empiric |

| Model Structure | Physiologically defined compartments representing organs/tissues | Empirical compartments (e.g., central, peripheral) |

| Primary Inputs | Drug physicochemical properties, in vitro data, physiological parameters | Observed clinical concentration-time data |

| Variability Assessment | Typically describes average subject; limited inter-individual variability | Estimates inter-individual and residual variability |

| Key Applications | Early development: First-in-human prediction, DDI risk assessment, formulation screening | Late development: Covariate effect quantification, dose optimization in specific populations |

| Regulatory Use | Drug-drug interactions, pediatric extrapolation, biowaivers [41] [38] | Bridging studies, dose justification in special populations, label claims [40] |

| Strengths | Predicts PK before clinical data; simulates tissue concentrations; mechanistic insight | Handles sparse data; quantifies population variability; statistically robust |

| Limitations | Complex parameterization; requires extensive compound data; limited variability assessment | Limited extrapolation capability; requires clinical data; less mechanistic insight |

Table 2: Data requirements and applications across the drug development continuum

| Aspect | PBPK Modeling | Pop-PK Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Data Requirements | In vitro ADME data, physicochemical properties, enzyme/transporter kinetics [38] | Clinical PK data from studied populations [35] |

| Early Development Applications | Predicting human PK from preclinical data, lead optimization, first-in-human dose selection [38] | Limited application (requires clinical data) |

| Late Development Applications | DDI risk assessment, special population simulations, formulation development [42] [41] | Covariate analysis, dose individualization, exposure-response modeling [40] |

| Special Population Predictions | Pediatric extrapolation, organ impairment, pregnancy [43] [44] [41] | Extrapolation within studied population range [35] |

| Output | Full concentration-time profiles in plasma and tissues | Population parameter estimates and variability |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

PBPK Model Development Protocol

The development of a robust PBPK model follows a systematic "predict-learn-confirm" cycle [39]:

Step 1: System Data Collection

- Gather physiological parameters for target population (organ weights, blood flows, enzyme abundances)

- Compile demographic information (age, weight, height distributions) [38] [39]

Step 2: Drug Parameter Acquisition

- Determine physicochemical properties (molecular weight, logP, pKa)

- Measure in vitro parameters (plasma protein binding, blood-to-plasma ratio, permeability)

- Quantify metabolic stability (hepatocyte/microsomal clearance, CYP reaction phenotyping)

- Assess transporter affinity where relevant [38]

Step 3: Model Building and Verification

- Implement mathematical structure using specialized software (e.g., GastroPlus, PK-Sim, Simcyp)

- Verify model performance against preclinical PK data in relevant species

- Evaluate predictive accuracy for human PK parameters [38]

Step 4: Model Refinement and Application

- Refine parameters using early clinical data if available ("middle-out" approach)

- Simulate untested scenarios (DDIs, special populations, dosing regimens) [38] [39]

- Conduct sensitivity analysis to identify critical parameters [41]

Pop-PK Model Development Protocol

Pop-PK analysis follows a structured statistical approach to model development:

Step 1: Data Assembly

- Collect all available concentration-time data across studies

- Compile covariate information (demographics, laboratory values, comorbidities)

- Ensure data quality and appropriate assay characterization [35]

Step 2: Base Model Development

- Select structural model (1-, 2-, or 3-compartment)

- Estimate population parameters and variability components

- Assess goodness-of-fit and model stability [35]

Step 3: Covariate Model Building

- Test plausible relationships between covariates and PK parameters

- Use stepwise approaches (forward inclusion/backward elimination)

- Evaluate statistical significance and clinical relevance [35]

Step 4: Model Validation

- Conduct internal validation (bootstrap, visual predictive check)

- Perform external validation if independent dataset available

- Evaluate simulation properties for intended applications [35]

Step 5: Model Application

- Simulate exposure in target populations

- Optimize dosing regimens based on covariate relationships

- Support regulatory submissions and labeling [40]

Research Reagents and Essential Tools

Table 3: Key research reagents and software solutions for PBPK and Pop-PK modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBPK Software Platforms | PK-Sim, Simcyp, GastroPlus | Implement PBPK model structure and simulations | Whole-body PBPK model development and simulation [38] |

| Pop-PK Software Platforms | NONMEM, Monolix, R/phoenix | Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling | Population PK/PD model development and covariate analysis [35] |

| In Vitro Systems for PBPK | Human liver microsomes, Hepatocytes, Caco-2 cells | Generate drug-specific metabolism and transport parameters | Quantifying intrinsic clearance, permeability, and transporter interactions [38] |

| Analytical Instruments | LC-MS/MS systems | Quantify drug concentrations in biological matrices | Generating PK data for Pop-PK model development [38] |

| Physiological Databases | ICVP, PK-Sim Ontogeny Database | Provide system-specific parameters for PBPK | Incorporating age-dependent physiology and enzyme maturation [44] |

Cross-Species Extrapolation in Comparative Pharmacokinetics

The fundamental differences between PBPK and Pop-PK become particularly significant in cross-species extrapolation, which is essential in translational research. PBPK models excel in this domain because they explicitly incorporate species-specific physiological parameters [44] [38]. By replacing human organ weights, blood flows, and enzyme abundances with corresponding values from preclinical species, PBPK models can predict human PK based on animal data and in vitro information [38]. This capability is particularly valuable for first-in-human dose predictions and estimating clinical starting doses [38].

Pop-PK approaches, while powerful for analyzing human data, have limited application in cross-species prediction due to their empirical nature. However, Pop-PK can be applied within animal species to understand between-animal variability in preclinical models, which can inform human study design [35]. The integration of PBPK predictions followed by Pop-PK analysis of clinical data represents a powerful "learn-and-confirm" paradigm in drug development [43] [39].

For pediatric extrapolation, PBPK models can incorporate ontogeny profiles of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters to predict PK across childhood development stages [44]. This approach was successfully demonstrated in the development of moxifloxacin for pediatric populations, where PBPK models informed age-dependent dosing regimens that were subsequently confirmed via Pop-PK analysis of clinical data [43].

Pop-PK and PBPK modeling represent complementary methodologies with distinct strengths and applications in drug development. PBPK's mechanistic, bottom-up approach provides powerful predictive capabilities early in development and enables extrapolation to unstudied populations, including cross-species predictions [38] [39]. Pop-PK's empirical, top-down approach delivers robust quantification of variability and covariate effects in studied populations [35] [40]. The ongoing integration of these approaches—using PBPK for prospective predictions and Pop-PK for analysis of clinical data—represents the state-of-the-art in model-informed drug development, enabling more efficient drug development and optimized dosing strategies across diverse populations [43] [39].

Article | Publish Comparison Guides | Comparative Pharmacokinetics

In the field of drug development, successfully translating pharmacokinetic (PK) data from animal studies to humans is a critical and challenging step. *Allometric scaling provides a empirical yet powerful mathematical framework for this task, enabling the prediction of human PK parameters—such as clearance (CL), volume of distribution (Vss), and half-life (t½)—based on data from preclinical animal species [45] [46]. This methodology is grounded in the principle that many physiological and anatomical processes scale predictably with body size across mammalian species [47] [48]. While its theoretical foundation, particularly the use of a fixed universal exponent, is a subject of ongoing debate [49], allometric scaling remains a cornerstone in drug discovery for making early go/no-go decisions and designing first-in-human (FIH) clinical trials [46] [50]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various allometric scaling methods and alternatives, providing a detailed overview of their principles, applications, and inherent limitations within comparative pharmacokinetics research.

Fundamental Principles of Allometric Scaling

Allometric scaling describes the quantitative relationship between the size of an organism and its biological functions, from whole-body metabolic rate to organ-level physiology.

The Allometric Power Law

The core principle is expressed by the power law equation: Y = a × W^b^, where:

- Y is the biological or pharmacokinetic parameter of interest (e.g., clearance, metabolic rate).

- W is the body weight.

- a is the allometric coefficient, a drug-specific constant.

- b is the allometric exponent, which varies based on the type of parameter [47] [51].

This non-linear relationship explains why a simple mg/kg dose conversion across species is often inaccurate, as it tends to overdose large animals and underdose small ones [47].

Theoretical and Empirical Origins

The practice originates from ecology and the study of metabolic rates. A key empirical observation, *Kleiber's law, established that the basal metabolic rate (BMR) scales with body weight to the power of 0.75 (W^0.75^) [49] [48]. The influential *West, Brown, and Enquist (WBE) framework proposed a theoretical explanation for this 0.75 exponent, based on the fractal nature of nutrient supply networks (e.g., circulatory systems) that fill an organism's volume and are constrained by energy minimization principles [49]. In pharmacology, these principles are extrapolated, assuming that drug clearance, which is often limited by blood flow rates linked to metabolic processes, may also scale with an exponent of 0.75 [49] [51].

From Metabolic Rate to Pharmacokinetic Parameters

The extrapolation applies specific exponents to different PK parameters, grounded in physiological principles:

- Clearance (CL): Often scaled with an exponent (b) of 0.75, analogous to metabolic rate and hepatic blood flow [51].

- Volume of Distribution (V): Typically scaled with an exponent (b) of 1.0, assuming it is proportional to body weight and fluid volumes [51].

- Half-life (t½): Scaled with an exponent (b) of 0.25, derived from the relationship t½ = (0.693 × V) / CL [51].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for applying these principles in a pharmacokinetic study.

Methodological Approaches and Comparison

Multiple scaling methods have been developed, ranging from simple empirical approaches to complex mechanistic models. The table below compares their core features, advantages, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Allometric Scaling and Alternative Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations & Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Allometry [47] [50] | Direct application of power law (Y = aW^b^) to animal PK data. | Body weight and PK parameters from ≥ 3 animal species. | Simple, fast, inexpensive; useful for early go/no-go decisions [50]. | Less accurate for drugs with significant species-specific metabolism. Fold error: ~2.0-2.25 for human CL and V~ss~ prediction [50]. |

| Fixed Exponent Scaling [51] | Uses pre-defined exponents (e.g., CL=0.75, V=1.0). | Body weight and PK parameters from a single species (often rat). | Extremely simple; allows rapid initial estimates. | Assumes universality, which is often invalid [49]. Accuracy is highly variable and drug-dependent. |

| In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) [46] | Integrates in vitro data (e.g., metabolism, protein binding) with allometry. | Animal PK data + in vitro data (e.g., hepatocyte clearance, f~u~). | Incorporates drug-specific properties; can improve prediction for metabolized drugs. | More complex than simple allometry; requires quality in vitro data. |

| Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling [46] [51] | Mechanistic model simulating drug disposition based on human physiology and drug properties. | Extensive data on system-specific physiology, drug physicochemical properties, and in vitro ADME. | Most accurate and robust; can simulate various scenarios and populations. | Resource-intensive; requires very rich data input and expertise [46]. |

Applications in Drug Development and Research

Allometric scaling is a versatile tool applied across the drug development pipeline, from discovery to clinical dose selection.

- First-in-Human (FIH) Dose Selection: A primary application is predicting a safe Maximum Recommended Starting Dose (MRSD) for clinical trials. This often involves calculating a Human Equivalent Dose (HED) from animal toxicology studies, such as the No-Observed-Adverse-Effect-Level (NOAEL), corrected for body surface area using factors (K~m~) [52] [46]. This approach is recommended by regulatory bodies like the FDA.

- Interspecies Pharmacokinetic Prediction: As demonstrated in Table 1, simple allometry can predict human clearance and volume of distribution from rat data with reasonable accuracy for a wide range of drugs, facilitating early candidate selection [50].

- Extrapolation to Special Populations: Allometric principles are used to scale drug doses from adults to pediatric populations across different ages and body weights, and to adjust for body size in obese patients [49] [53]. However, this requires careful consideration of ontogeny and maturation of drug-metabolizing enzymes in children [53].

- Veterinary Medicine and Zoo Pharmacology: The technique is crucial for determining appropriate drug doses for a wide variety of animal species, from pets to wildlife, where specific PK data is often lacking [45] [47].

Examination of Limitations and Inherent Challenges

Despite its utility, allometric scaling is not a universal law and has several well-documented limitations that researchers must consider.

- The Debate on a Universal Exponent: A significant body of evidence challenges the existence of a single, universal allometric exponent. The 0.75 exponent, while commonly used, is not always accurate, as the true exponent varies based on drug-specific properties and the physiological variables underlying clearance [49]. A critical review suggests moving from a search for a universal "Newtonian" law to a "Darwinian" approach that embraces and explains variability [49].

- Impact of Species-Specific Differences: Scaling accuracy can be poor for drugs affected by factors that are not similar across species. These include [47]:

- Differences in Drug Metabolism: Variations in enzyme expression, function, and metabolic pathways (e.g., dogs lack acetylation metabolism).

- Protein Binding: Differences in plasma protein affinity and capacity.

- Active Transporters: Species differences in the expression and function of uptake/efflux transporters in tissues like the liver and kidney.

- Route of Elimination: Drugs with significant biliary excretion (especially those with molecular weight >350) often deviate from predictions [47].

- Limited Predictive Power for Certain Drugs: Simple allometry often fails for drugs that are highly protein-bound, undergo extensive metabolism with major species differences, or are substrates for active renal secretion [47].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

To ensure reliable results, allometric scaling must be applied using a standardized methodology and validated with experimental data.

Detailed Protocol for Simple Allometry

The following workflow, derived from established practices, outlines the key steps for predicting human pharmacokinetic parameters [47] [51] [50]:

- Data Collection: Gather pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., Clearance - CL, Volume of distribution at steady state - V~ss~, Half-life - t~½~) from in vivo studies in at least three animal species (e.g., rat, dog, monkey) that span a wide body weight range.

- Logarithmic Transformation: Convert the values of the PK parameter (Y) and the corresponding body weights (W) of each species into logarithmic values (base 10).

- Linear Regression Analysis: Perform a linear regression of log Y against log W using statistical software. The equation of the line is: log Y = b log W + log a.

- Determine Allometric Coefficients: From the regression:

- The slope of the line is the allometric exponent (b).

- The anti-logarithm of the y-intercept is the allometric coefficient (a).

- Predict Human Parameters: Substitute the estimated human body weight (e.g., 70 kg) into the power equation Y = a × W^b^ to predict the human PK parameter.

- Model Validation: Quantify prediction accuracy by comparing extrapolated values with observed human data, often expressed as Mean Error (ME %): ME = [(Extrapolated Value - Observed Value) / Observed Value] × 100 [47].

Case Study: Propofol and Nanochelators

- Propofol Cross-Species Scaling: A study scaling propofol PK from rats to children and adults demonstrated strong allometric relationships. The exponents for clearance (0.78), volume (0.98), and other parameters aligned closely with theoretical values, and model predictions adequately described concentrations in critically ill patients [51].

- Nanochelator Pharmacokinetics: Allometric scaling was successfully applied to predict the PK of a novel deferoxamine nanochelator (DFO-NP) in mice and humans based on rat data. The study used specific exponents (0.75 for clearance, 1 for volumes) and validated the predictions against experimental mouse data, supporting its clinical translatability [54].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Allometric Scaling Studies

| Category | Essential Material / Reagent | Critical Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Models | Preclinical Species (e.g., Mouse, Rat, Dog, Monkey) | Provides the core pharmacokinetic data (CL, V~ss~, t~½~) from which human parameters are extrapolated. |

| Bioanalytical Tools | HPLC Systems with UV/Fluorescence/ Mass Spectrometry Detection | Used to quantify drug concentrations in biological matrices (e.g., plasma, blood) from animal and human studies. |

| Software & Computation | PK/PD Modeling Software (e.g., Phoenix WinNonlin, NONMEM) | Facilitates regression analysis, model fitting, parameter estimation, and simulation of concentration-time profiles. |

| In Vitro Systems | Hepatocytes, Microsomes, Plasma Protein Binding Assays | Provides data on drug metabolism and protein binding for IVIVE and PBPK approaches, improving prediction accuracy. |

The following graph visualizes the decision-making framework a scientist might use to select the most appropriate scaling method based on the available data and project goals.

Allometric scaling is an indispensable, though imperfect, tool in the toolkit of comparative pharmacokinetists and drug developers. Its power lies in providing rapid, data-driven initial estimates of human pharmacokinetics and safe starting doses, thereby de-risking the early stages of clinical development [45] [46]. However, the field is moving beyond the assumption of a universal scaling law. The future of accurate interspecies extrapolation lies in a more nuanced approach that integrates the principles of allometry with drug-specific properties (e.g., elimination route, protein binding) and patient-specific factors (e.g., age, organ function) [49] [53]. While sophisticated methods like PBPK modeling represent the gold standard for accuracy, simple allometric methods retain significant value for making early, strategic decisions in drug discovery and development.

Model-Informed Precision Dosing (MIPD) in Oncology and CNS Disorders