Controlled Vocabularies in Ecotoxicology: Building a Foundation for Reliable Data and Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to controlled vocabularies (CVs) in ecotoxicology, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Controlled Vocabularies in Ecotoxicology: Building a Foundation for Reliable Data and Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to controlled vocabularies (CVs) in ecotoxicology, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational role of CVs in organizing complex toxicity data, as exemplified by major resources like the ECOTOX Knowledgebase. The content details methodological approaches for implementing CVs, addresses common challenges in data curation and integration, and presents frameworks for validating data reliability. By establishing a clear understanding of how standardized terminology enhances data findability, interoperability, and reuse, this article aims to support more robust environmental risk assessments and chemical safety evaluations.

What Are Controlled Vocabularies and Why Are They Critical in Ecotoxicology?

In the realm of ecotoxicity data research, the standardization of terminology is not merely a convenience but a fundamental requirement for data integrity, interoperability, and reuse. A controlled vocabulary is an authoritative set of terms selected and defined based on the requirements set out by the user group, used to ensure consistent indexing or description of data or information [1]. These vocabularies do not necessarily possess inherent structure or relationships between terms but serve as the foundational layer for creating standardized knowledge systems.

The critical importance of controlled vocabularies becomes apparent when dealing with complex data extraction processes, such as in systematic reviews of toxicological end points from primary sources. Primary source language describing treatment-related end points can vary greatly, resulting in large labor efforts to manually standardize extractions before data are fit for use [1]. In ecotoxicity research, where data informs critical public health and regulatory decisions, this consistency is paramount. Without standardized annotation, divergent language describing study parameters and end points inhibits crosstalk among individual studies and resources, preventing meaningful synthesis of data across studies and ultimately compromising the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles that govern modern scientific data management [1].

Core Concepts and Terminology

Hierarchical Organization of Knowledge Systems

Knowledge organization systems exist on a spectrum of complexity and structure, each serving distinct purposes in information management:

- Term Lists: The simplest form, consisting of authorized terms with limited relationships

- Taxonomies: Hierarchical classification systems that organize concepts into categories and subcategories

- Thesauri: Controlled vocabularies that explicitly specify semantic relationships between concepts, including equivalence, hierarchical, and associative relationships

- Ontologies: Complex knowledge representations that define concepts and their relationships with formal logic, enabling computational reasoning and inference [1]

Foundational Terminology Table

Table 1: Core Terminology in Controlled Vocabulary Development

| Term | Definition | Application in Ecotoxicity |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Vocabulary | An authoritative set of standardized terms used to ensure consistent data description [1] | Standardizing terms for toxicological end points such as "hepatocellular hypertrophy" |

| SKOS (Simple Knowledge Organization System) | A W3C standard to support the use of knowledge organization systems within the Semantic Web framework [2] | Representing ecotoxicity thesauri in linked data formats |

| Indexing Language | The set of terms used in an index to represent topics or features of documents [3] | Cataloging developmental toxicity study outcomes |

| Crosswalk | A mapping that shows how terms in different vocabularies correspond to each other [1] | Aligning UMLS, OECD, and BfR DevTox terms for data harmonization |

| Precoordination | Combining multiple concepts into a single term (e.g., "head_small") [1] | Describing complex morphological abnormalities in developmental studies |

| Compositionality | The degree to which terms are formed by combining reusable semantic components [3] | Building complex toxicity findings from basic anatomical and effect terms |

SKOS Standards Framework

The Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) is a W3C-developed area of work producing specifications and standards to support the use of knowledge organization systems such as thesauri, classification schemes, subject heading lists, and taxonomies within the framework of the Semantic Web [2]. SKOS provides a standardized, machine-readable framework for representing controlled vocabularies, enabling them to be shared and linked across the web.

SKOS became a W3C Recommendation in August 2009, representing a significant milestone in bridging the world of knowledge organization systems with the linked data community [2]. This standard brings substantial benefits to libraries, museums, government portals, enterprises, and research communities that manage large collections of scientific data, including ecotoxicity resources. The alignment between SKOS and the ISO 25964 thesaurus standard further enhances its utility as an international framework for vocabulary representation [2].

The core SKOS data model organizes knowledge through several fundamental properties and relationships. Concepts are labeled using preferred, alternative, and hidden terms, while semantic relationships are established through broader, narrower, and related associations. Additionally, SKOS supports documentation through scope notes, definitions, and examples, as well as grouping concepts into concept schemes and collections for enhanced organization.

Quantitative Comparison Metrics for Indexing Languages

Intra-Term Set Measurement Protocols

The quantitative characterization of indexing languages enables empirical, reproducible comparison between different vocabulary systems. These metrics are divided into two primary categories: intra-set measurements that describe the internal structure of a single term set, and inter-set measurements that compare overlaps between different term sets [3].

Table 2: Intra-Term Set Metrics for Vocabulary Analysis

| Metric | Measurement Protocol | Interpretation in Ecotoxicity Context |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Distinct Terms | Count of syntactically unique terms in the set [3] | Indicates coverage and granularity of toxicity concepts |

| Term Length Distribution | Descriptive statistics (mean, median) of character counts per term [3] | Reflects specificity and precoordination level of end point descriptions |

| Observed Linguistic Precoordination | Categorization of terms as uniterms, duplets, triplets, or quadruplets+ based on syntactic separators [3] | Measures compositional structure in morphological abnormality terms |

| Flexibility Score | Fraction of sub-terms that also appear as uniterms [3] | Indicates reusability of semantic components in developmental toxicology |

| Compositionality | Number of terms containing another complete term as a proper substring [3] | Reveals semantic factoring in complex pathological findings |

Inter-Term Set Comparison Methodology

The protocol for comparing different controlled vocabularies involves calculating overlap metrics that reveal the degree of alignment between systems:

- Term Set Preparation: Extract complete term lists from each vocabulary system to be compared

- Normalization: Apply consistent case-folding, punctuation removal, and stemming to enable fair comparison

- Exact Match Calculation: Compute the Jaccard similarity coefficient as the size of the intersection divided by the size of the union of the two term sets

- Semantic Similarity Assessment: Employ advanced natural language processing techniques to identify related terms beyond exact string matches

- Structural Alignment Analysis: Map hierarchical relationships and property structures between the vocabularies

Application Protocol: Implementing Controlled Vocabularies for Ecotoxicity Data

Experimental Protocol: Automated Vocabulary Mapping for Toxicological End Points

The following protocol details a proven methodology for standardizing extracted ecotoxicity data using automated application of controlled vocabularies, adapted from successful implementation in developmental toxicology studies [1].

Objective: To minimize labor efforts in standardizing extracted toxicological end points through an augmented intelligence approach that automatically applies preexisting controlled vocabularies.

Materials and Reagents:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Vocabulary Mapping

| Item | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Source Data | Extracted end points from prenatal developmental toxicology studies (approx. 34,000 extractions) [1] | Provides raw terminology for standardization |

| Vocabulary Crosswalk | Harmonized mapping between UMLS, OECD, and BfR DevTox terms [1] | Serves as reference for standardized terminology |

| Annotation Code | Python 3 (version 3.7) scripts for automated term matching [1] | Executes the computational mapping process |

| Validation Dataset | Manually curated subset of extracted end points (≥500 terms) | Provides ground truth for performance evaluation |

Procedure:

Crosswalk Development Phase:

- Create a harmonized controlled vocabulary crosswalk containing Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) codes, German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) DevTox harmonized terms, and The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) end point vocabularies [1]

- Establish semantic relationships between equivalent terms across the three vocabulary systems

- Document hierarchy and mapping rules for complex term relationships

Automated Mapping Phase:

- Apply annotation code to match extracted end point language to controlled vocabulary terms

- Implement fuzzy matching algorithms to handle spelling variations and synonyms

- Generate confidence scores for each automated mapping decision

Validation and Quality Control Phase:

- Manually review a statistically significant sample of automated mappings (approximately 51% of total) for potential extraneous matches or inaccuracies [1]

- Identify patterns in terms that resist automated mapping (typically overly general terms or those requiring human logic)

- Calculate performance metrics including precision, recall, and mapping coverage

Implementation Phase:

- Apply standardized controlled vocabulary terms to the successfully mapped extractions

- Document unmapped terms for future vocabulary expansion

- Generate FAIR-compliant dataset for downstream analysis

Expected Outcomes:

- Automatic application of standardized controlled vocabulary terms to 75% of extracted end points from guideline studies [1]

- Significant reduction in manual standardization effort (estimated savings of >350 hours) [1]

- Production of computationally accessible, standardized developmental toxicity datasets

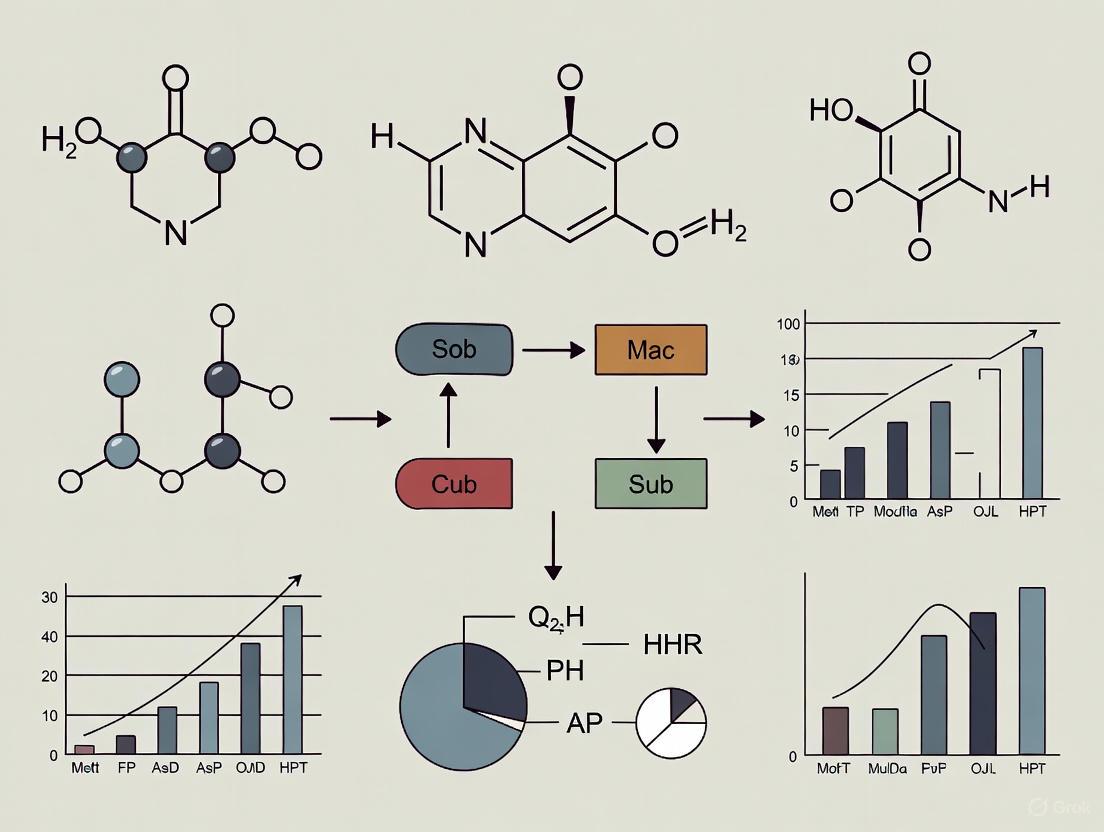

Visualizing Vocabulary Mapping Workflow

Diagram Title: Automated Vocabulary Mapping Process

Advanced Applications in Ecotoxicity Research

Protocol for Cross-Study Data Integration

The integration of ecotoxicity data across multiple studies and research domains requires sophisticated vocabulary alignment techniques. The following protocol enables semantic interoperability between disparate data sources:

Source Vocabulary Analysis:

- Apply intra-term set metrics to characterize each source vocabulary's size, term length distribution, and compositionality [3]

- Identify structural patterns and semantic factoring within each terminology system

Intersection Mapping:

- Calculate pairwise Jaccard similarity coefficients between all vocabulary pairs

- Identify core concept overlap and domain-specific extensions

- Map hierarchical relationships across vocabulary boundaries

SKOS Representation:

- Convert aligned vocabulary to SKOS format using standardized predicates (skos:prefLabel, skos:broader, skos:narrower) [2]

- Publish linked data vocabulary for Semantic Web applications

Query Federation:

- Implement SPARQL endpoints for each standardized vocabulary

- Enable cross-database queries using aligned semantic concepts

Augmented Intelligence Implementation

The successful application of automated vocabulary mapping in developmental toxicology demonstrates the power of augmented intelligence approaches [1]. This methodology combines computational efficiency with human expertise through:

- Automated Processing: Handling routine, high-confidence mappings algorithmically

- Human Oversight: Applying expert judgment to complex cases and ambiguity resolution

- Continuous Improvement: Using manual corrections to refine automated algorithms

- Resource Generation: Producing reusable assets including controlled vocabulary crosswalks, organized related terms lists, and customizable code for implementation in other study types [1]

This approach has proven particularly valuable for standardizing legacy developmental toxicology datasets, where historical terminology variations present significant challenges for contemporary computational toxicology and predictive modeling applications.

The systematic implementation of controlled vocabularies, standardized through frameworks like SKOS and applied via rigorous protocols such as those described herein, represents a transformative methodology for ecotoxicity data research. By moving from ad hoc terminology to structured, computable knowledge organization systems, researchers can unlock the full potential of existing and future toxicity data. The quantitative metrics, automated mapping protocols, and visualization approaches detailed in these application notes provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical tools for enhancing data interoperability, supporting validation of alternative methods, and ultimately strengthening the scientific foundation for chemical risk assessment and regulatory decision-making.

Application Note: The Scale and Diversity of Ecotoxicity Data

The evaluation of chemical safety relies on the systematic compilation and curation of ecotoxicity data. The volume and variety of this data present significant challenges, underscoring the critical need for standardized curation processes and controlled vocabularies to ensure reusability and interoperability.

Table 1: Scope and Scale of Publicly Available Ecotoxicity and Toxicology Databases

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Number of Chemicals | Number of Records/Results | Key Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX [4] | Ecological toxicity | >12,000 | >1,100,000 test results | Single-chemical ecotoxicity tests for aquatic and terrestrial species. |

| ToxValDB (v9.6.1) [5] | Human health toxicity | 41,769 | 242,149 records | Experimental & derived toxicity values, exposure guidelines. |

| ToxRefDB [6] | In vivo animal toxicity | >1,000 | Data from >6,000 studies | Detailed in vivo study data from guideline-like studies. |

| ADORE [7] | Acute aquatic toxicity (ML-ready) | Not Specified | Extracted from ECOTOX | Curated acute mortality data for fish, crustaceans, and algae, expanded with chemical & species features. |

The Data Variety Challenge

The variety in ecotoxicity data manifests across multiple dimensions, necessitating robust controlled vocabularies for meaningful integration:

- Taxonomic Diversity: Databases like ECOTOX encompass over 14,000 species, requiring consistent taxonomic classification [4].

- Experimental Endpoints: A single effect, such as mortality, can be represented by different measured endpoints (e.g., LC50, EC50) which must be clearly defined and categorized [7].

- Experimental Variables: Critical factors such as exposure duration, test medium, and organism life stage introduce significant variability that must be captured with standardized terminology [4] [7].

Protocol: Systematic Data Curation and Integration Workflow

This protocol details a standardized procedure for curating ecotoxicity data from primary sources, emphasizing the use of controlled vocabularies to support computational toxicology and research.

Experimental Workflow for Data Curation

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage pipeline for processing ecotoxicity data, from initial acquisition to final standardized output.

Reagent and Resource Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Ecotoxicology

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase [4] | Authoritative source for curated single-chemical ecotoxicity data. | Over 1 million test results; systematic review procedures; FAIR data principles. |

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [6] | Chemistry resource supporting computational toxicology. | Provides DSSTox Substance IDs (DTXSID), chemical structures, and property data. |

| DataFishing Tool [8] | Python script/web form for automated data retrieval from multiple biological databases. | Efficiently obtains taxonomic, DNA sequence, and conservation status data. |

| ToxValDB [5] | Compiled resource of human health-relevant toxicity data. | Standardized format for experimental and derived toxicity values from multiple sources. |

| ADORE Dataset [7] | Benchmark dataset for machine learning in aquatic ecotoxicology. | Curated acute toxicity data with chemical, phylogenetic, and species-specific features. |

Detailed Procedural Steps

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Harmonization

- Input Sources: Download core data files (e.g., species, tests, results) from authoritative sources like the ECOTOX downloadable ASCII files [7].

- Identifier Mapping: Retain and map critical chemical identifiers, including CAS numbers, DSSTox Substance IDs (DTXSID), and InChIKeys, to ensure traceability and integration with other chemical resources [7].

Step 2: Application of Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

- Taxonomic Filtering: Retain data only for relevant taxonomic groups (e.g., Filter

ecotox_groupfor "Fish", "Crusta", "Algae") [7]. - Endpoint Selection: Define and select relevant toxicity endpoints based on standardized test guidelines. For example:

- Study Type Exclusion: Remove data from in vitro tests and assays based on early life stages (e.g., eggs, embryos) if the objective is to model adult organism toxicity [7].

Step 3: Vocabulary Control and Metadata Curation

- Taxonomy Curation: Ensure species entries have complete taxonomic data (Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species). Remove entries with missing critical classification data [7].

- Effect and Endpoint Mapping: Categorize all effects and endpoints using a controlled vocabulary. For example, map various reported effects to standardized categories like "MOR," "GRO," etc. [7].

- Experimental Condition Annotation: Extract and codify key experimental conditions such as exposure duration, test medium, and organism life stage using predefined terms [4].

Step 4: Data Standardization and Value Conversion

- Unit Standardization: Convert all concentration values to a standard unit (e.g., mg/L or mol/L). Molar concentrations are often preferred for QSAR and machine learning as they are more biologically informative [7].

- Value Deduplication: Implement a quality control (QC) workflow to identify and resolve duplicate records from multiple sources, a process used in ToxValDB development [5].

Step 5: Feature Expansion and Dataset Integration

- Chemical Descriptor Addition: Expand the dataset with chemical features such as canonical SMILES, molecular representations, and physicochemical properties from resources like PubChem and the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [7].

- Species Feature Integration: Add phylogenetic and species-specific traits to enable analyses that consider evolutionary relationships [7].

- Data Structuring: Output the final curated data in a structured, machine-readable format (e.g., CSV, SQL database) for subsequent analysis and modeling.

Protocol: Implementing a Controlled Vocabulary for Data Curation

The implementation of a consistent controlled vocabulary is fundamental to overcoming the variety challenge in ecotoxicity data.

Logical Framework for Vocabulary Implementation

The relationship between core data entities and the controlled vocabularies that structure them is illustrated below.

Procedures for Vocabulary Management

- Vocabulary Development: Define and maintain lists of approved terms for critical data fields. This includes standardized terms for taxonomic classification, observed effects, measured endpoints, and experimental conditions [4] [7].

- Data Curation Pipeline: Incorporate vocabulary mapping as a distinct step in the data processing workflow, ensuring all incoming data is translated into the controlled terms before integration into the master database [5].

- Quality Control Checks: Implement automated checks to flag values that do not conform to the controlled vocabulary, allowing for curator review and corrective action, thereby maintaining data integrity [5].

Adherence to these detailed protocols enables the transformation of disparate, complex ecotoxicity data into a structured, standardized resource. This structured data is essential for advancing computational toxicology, developing predictive models, and supporting robust chemical safety assessments.

The ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX) stands as the world's largest compilation of curated ecotoxicity data, housing over one million test results for more than 12,000 chemicals and 13,000 species from over 53,000 scientific references [9] [10]. This monumental achievement in data management is underpinned by a rigorous, systematic application of controlled vocabularies (CVs). This case study details how ECOTOX employs CVs to ensure data consistency, enhance interoperability, and support robust environmental research and chemical risk assessments, contributing to a broader framework for reliable ecotoxicity data research.

In the field of ecotoxicology, the diversity of terminology used across thousands of scientific studies presents a significant challenge for data integration and reuse. Controlled vocabularies are predefined, standardized sets of terms used to consistently tag and categorize data. Within ECOTOX, these CVs provide the necessary semantic structure to transform free-text information from disparate literature sources into a harmonized, query-ready knowledgebase [10]. This practice is fundamental to making the data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR).

The ECOTOX Data Curation Pipeline: A Systematic Workflow

The process of incorporating data into ECOTOX is a meticulously designed pipeline that ensures only relevant, high-quality studies are added, with all information translated into a consistent language of controlled terms. The workflow, summarized in the diagram below, involves multiple stages of screening and extraction [10].

Protocol: Literature Review and Data Curation Pipeline

The ECOTOX team follows standardized protocols aligned with systematic review practices to identify and curate ecotoxicity data [10] [11].

Step 1: Literature Search and Acquisition

- Objective: Comprehensively identify potentially relevant ecotoxicity studies from the open scientific literature.

- Methods: Develop and execute customized search strings for chemicals of interest across multiple bibliographic databases. Grey literature, including government technical reports, is also included [10].

Step 2: Citation Screening for Applicability

- Objective: Filter references to retain only those reporting on ecologically relevant species and single-chemical exposures.

- Methods: Review titles and abstracts against predefined eligibility criteria (e.g., presence of an ecologically relevant species, a single chemical stressor, and a measurable effect) [10]. This step significantly reduces the volume of references for full-text review.

Step 3: Full-Text Review for Acceptability

- Objective: Assess the methodological quality and reporting adequacy of the study.

- Methods: Review the full text of articles against criteria for scientific rigor. Studies must include, for example, documented control groups and reported concentration-response relationships to be accepted for data extraction [10].

Step 4: Data Abstraction and Controlled Vocabulary Application

- Objective: Systematically extract and standardize key information from accepted studies.

- Methods: Trained curators extract pertinent details into structured data fields. This is the critical stage where controlled vocabularies are applied to describe:

- Chemical: Using identifiers like CAS numbers and DSSTox Substance IDs (DTXSID) for interoperability with other databases like the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [9] [7].

- Species: Taxonomic information (species, genus, family) is verified and standardized using integrated taxonomic resources [10].

- Effect and Endpoint: Observed biological effects (e.g., Mortality, Immobilization, Growth) and the quantified metrics (e.g., LC50, EC50) are mapped to standardized terms [7].

- Test Conditions: Experimental media, duration, and other methodological parameters are also described using controlled terms [10].

Step 5: Quality Assurance and Publication

Quantitative Scope of the ECOTOX Knowledgebase

The systematic and sustained application of this curation pipeline has resulted in a knowledgebase of remarkable scale and diversity. The following table summarizes the core data content of ECOTOX.

Table 1: Quantitative Data Inventory of the ECOTOX Knowledgebase (as of 2025) [9]

| Data Category | Count | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific References | > 53,000 | Peer-reviewed literature and grey literature sources. |

| Unique Chemicals | > 12,000 | Single chemical stressors, with links to CompTox Dashboard. |

| Ecological Species | > 13,000 | Aquatic and terrestrial plant and animal species. |

| Total Test Results | > 1,000,000 | Individual curated data records on chemical effects. |

The data covers a wide array of biological effects and endpoints, which are standardized using CVs. The table below illustrates common categories.

Table 2: Common Ecotoxicity Effects and Endpoints Standardized in ECOTOX [7]

| Taxonomic Group | Standardized Effect (CV) | Standardized Endpoint (CV) | Typical Test Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | Mortality (MOR) | LC50 (Lethal Concentration 50%) | 96 hours |

| Crustaceans | Mortality (MOR), Intoxication (ITX) | LC50 / EC50 (Effective Concentration 50%) | 48 hours |

| Algae | Growth (GRO), Population (POP) | EC50 (e.g., growth inhibition) | 72-96 hours |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Researchers leveraging ECOTOX or building similar curated systems utilize a suite of key resources and tools. The following table details these essential components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Ecotoxicity Data Curation

| Item Name | Function in Research / Curation | Relevance to ECOTOX |

|---|---|---|

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | A comprehensive chemistry database and web-based suite of tools. | Provides verified chemical identifiers (DTXSID) and properties, ensuring chemical data interoperability [9] [7]. |

| Controlled Vocabularies (CVs) | Standardized lists of terms for effects, endpoints, species, etc. | The core system for normalizing data from thousands of disparate studies, enabling reliable search and analysis [10]. |

| Systematic Review Protocols | A framework for identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing scientific evidence. | ECOTOX's curation pipeline is built on these principles, ensuring transparency, objectivity, and consistency [10] [11]. |

| ECOTOX User Interface (Ver 5) | The public-facing website for querying the knowledgebase. | Allows users to Search, Explore, and Visualize curated data using the underlying CVs for precise filtering [9]. |

| Azadirachtin B | Azadirachtin B, CAS:95507-03-2, MF:C33H42O14, MW:662.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Elaiomycin | Elaiomycin, CAS:23315-05-1, MF:C13H26N2O3, MW:258.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Functional Applications and Data Interoperability

The true value of a curated database is realized through its application. ECOTOX supports a wide range of ecological research and regulatory functions. The diagram below illustrates how the curated data flows to support key applications.

Support for Regulatory Decisions: ECOTOX data is used by local, state, and tribal governments to develop site-specific water quality criteria and to interpret environmental monitoring data for chemicals without established regulatory benchmarks [9]. It also informs ecological risk assessments for chemical registration under statutes like TSCA and FIFRA [9] [10].

Enabling Predictive Modeling: The high-quality, curated data in ECOTOX is essential for developing and validating Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models and other New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) [9] [12]. By providing reliable experimental data, it helps build machine learning models to predict toxicity, reducing reliance on animal testing [7] [12]. For instance, the ADORE dataset is a benchmark for machine learning derived from ECOTOX, specifically created to facilitate model comparison and advancement [7].

The ECOTOX Knowledgebase exemplifies the critical importance of controlled vocabularies in managing large-scale scientific data. Through a rigorous, systematic curation pipeline, ECOTOX transforms heterogeneous ecological toxicity information from the global literature into a structured, reliable, and interoperable resource. This foundational work not only supports immediate regulatory and research needs but also provides the essential empirical data required to develop the next generation of predictive toxicological models, thereby contributing to a more efficient and ethical future for chemical safety assessment.

The exponential growth of chemical substances in commerce necessitates robust frameworks for ecological risk assessment and research. Central to this challenge is the management of vast, heterogeneous ecotoxicity data. A controlled vocabulary serves as the foundational element, standardizing terminology for test methods, species, endpoints, and chemical properties to enable data integration and knowledge discovery [4]. This application note details how a well-defined controlled vocabulary system directly enables three core benefits within ecotoxicology: reliable data search, seamless data interoperability, and regulatory acceptance. Adherence to the protocols and utilizations of the resources described herein is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in chemical safety and ecological research.

The implementation of a controlled vocabulary is exemplified by the ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX), the world's largest curated compilation of ecotoxicity data [4]. The scale and diversity of data managed within this system underscore the necessity of a standardized terminology framework. The table below summarizes the quantitative scope of data enabled by this approach.

Table 1: Quantified Data Scope of the ECOTOX Knowledgebase (as of 2022)

| Data Category | Metric | Count / Volume |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Coverage | Unique Chemicals | > 12,000 chemicals [4] |

| Biological Species | Aquatic & Terrestrial Species | > 12,000 ecological species [4] |

| Test Results | Individual Toxicity Results | > 1 million test results [4] |

| Scientific References | Source Publications | > 50,000 references [4] |

| Data Sources | Aggregated Public Sources | > 1,000 worldwide sources [6] |

Core Benefit Analysis and Experimental Protocols

Enabling Reliable and Reproducible Search

A controlled vocabulary overcomes the challenge of inconsistent terminology in the scientific literature, which otherwise hampers data retrieval. By enforcing a unified set of terms for organisms, effects, and conditions, it ensures search queries are comprehensive and reproducible.

Experimental Protocol 1: Systematic Literature Search and Data Curation via ECOTOX

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying and curating ecotoxicity studies from the open literature, ensuring only relevant and acceptable data are incorporated into a knowledgebase [13] [4].

- Literature Sourcing: Conduct systematic searches of scientific databases (e.g., PubMed) using predefined search strategies tailored for ecologically relevant toxicity data for single chemicals [4].

- Initial Screening (Phase I): Apply strict acceptability criteria to identify relevant papers. A study must meet all the following minimum criteria to be accepted [13]:

- The toxic effects are related to single chemical exposure.

- The effects are on an aquatic or terrestrial plant or animal species.

- There is a biological effect on live, whole organisms.

- A concurrent environmental chemical concentration/dose or application rate is reported.

- There is an explicit duration of exposure.

- Data Extraction and Curation: For accepted studies, extract pertinent methodological details and results following well-established controlled vocabularies. This includes [4]:

- Chemical identification using standard identifiers (e.g., CAS RN, DTXSID).

- Test organism species and life stage.

- Detailed exposure conditions (duration, medium).

- Measured toxicity endpoints (e.g., LC50, EC50, NOEC) and values.

- Quality Control and Entry: Enter curated data into the knowledgebase using controlled vocabulary terms. Data is subjected to quality control checks before being made publicly available [4].

Facilitating Data Interoperability and Reusability

Controlled vocabularies act as a universal translator, allowing disparate datasets and computational tools to communicate effectively. This interoperability is a cornerstone of modern, integrated approaches to toxicology [6] [4].

Experimental Protocol 2: Integrating Curated Data with High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and Computational Tools

This protocol describes how curated in vivo data, standardized through a controlled vocabulary, is used to support and validate new approach methodologies (NAMs) and computational models [4].

- Data Export and Standardization: From a source like the ECOTOX Knowledgebase, export curated in vivo toxicity data for a set of chemicals of interest. Data is structured using standardized formats and identifiers [4].

- HTS Data Acquisition: Access corresponding high-throughput screening (HTS) data from programs such as ToxCast. These assays provide rapid, in vitro toxicity signatures for thousands of chemicals [6].

- Computational Modeling: Use the paired in vivo and in vitro data to build and validate quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models or other in silico prediction tools. The curated in vivo data serves as the biological anchor for model training and evaluation [4].

- Tool Interoperability: Leverage the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, which interlinks chemical structures, properties, toxicity data (e.g., ToxValDB), and exposure information. The shared use of a controlled vocabulary and standard chemical identifiers (DTXSID) across these EPA tools enables seamless navigation and data integration [6].

Table 2: Key U.S. EPA Tools for Integrated Chemical Safety Assessment

| Tool / Database Name | Primary Function | Role in Interoperability |

|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | Curated in vivo ecotoxicity data repository [4] | Provides foundational ecological effects data for modeling and assessment. |

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | Centralized access to chemical property and toxicity data [6] | Integrates data from multiple sources (ECOTOX, ToxCast, ToxValDB) using standardized chemical identifiers. |

| ToxCast | High-throughput in vitro screening assays [6] | Generates mechanistic toxicity data for chemical prioritization and predictive model development. |

| ToxValDB | Database of in vivo toxicity values and derived guideline values [6] | Provides standardized summary toxicity data from over 40 sources for comparison and use in assessments. |

Supporting Regulatory Acceptance and Standardization

Regulatory bodies require transparent, objective, and consistent data for risk assessment. A controlled vocabulary is integral to systematic review practices, providing the structure needed for study evaluation and use in regulatory decisions [13] [4].

Experimental Protocol 3: Evaluation of Open Literature Studies for Ecological Risk Assessment

This protocol, based on EPA Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) guidelines, details the process for reviewing open literature studies for use in regulatory ecological risk assessments, particularly for Registration Review and endangered species evaluations [13].

- Obtain Relevant Studies: Query the ECOTOX database to identify published open literature studies for the pesticide or chemical under review [13].

- Review Against Acceptance Criteria: Evaluate each study against a detailed set of OPP acceptance criteria, which expand upon the basic ECOTOX criteria. Key additional criteria include [13]:

- The toxicology information is for a chemical of concern to OPP.

- The article is a publicly available, full-text primary source in English.

- A calculated endpoint (e.g., LC50) is reported.

- Treatments are compared to an acceptable control.

- The study location (lab/field) and test species are reported and verified.

- Study Classification and Documentation: Classify the study based on its quality and relevance. Complete an Open Literature Review Summary (OLRS) for tracking and transparency [13].

- Incorporate into Risk Assessment: Use the accepted quantitative data to derive toxicity values (points of departure) for risk characterization or use data qualitatively to inform mode of action or for use in a weight-of-evidence approach [13].

Table 3: Key Resources for Curated Ecotoxicity Data and Analysis

| Resource Name | Type / Function | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | Curated Database | Authoritative source for single-chemical ecotoxicity data for aquatic and terrestrial species [4]. |

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | Data Integration Tool | Web-based application providing access to chemical structures, properties, bioactivity, and toxicity data from multiple EPA databases [6]. |

| ToxValDB | Toxicity Value Database | A large compilation of human health-relevant in vivo toxicology data and derived toxicity values from over 40 sources, designed for easy comparison [6]. |

| Controlled Vocabulary | Data Standardization Framework | A standardized set of terms for test methods, species, and endpoints that enables reliable search and data interoperability [4]. |

| OECD Document No. 54 | Statistical Guidance | Provides assistance on the statistical analysis of ecotoxicity data to ensure scientifically robust and harmonized evaluations (currently under revision) [14]. |

Implementing Controlled Vocabularies: From Theory to Practice in Data Systems

Application Note: Integrating Controlled Vocabularies in Ecotoxicity Research

In ecotoxicity research, structured processes for literature search, review, and data curation are critical for ensuring data reliability, reproducibility, and reusability. The exponential growth of chemical substances and associated toxicity data necessitates robust methodologies that can efficiently handle vast information volumes. This application note examines established pipelines and protocols, emphasizing the central role of controlled vocabularies in standardizing ecotoxicity data across research workflows. By implementing systematic approaches, researchers can enhance data interoperability and support computational toxicology applications, including machine learning and new approach methodologies (NAMs) [15] [7] [4].

The ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX) exemplifies the successful implementation of these principles, serving as the world's largest compilation of curated ecotoxicity data with over 12,000 chemicals and 1 million test results [4]. Similarly, the ADORE benchmark dataset demonstrates how structured curation practices facilitate machine learning applications in ecotoxicology [7]. These resources highlight how controlled vocabularies and standardized processes transform raw data into FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) resources for the research community.

Table 1: Key Databases and Resources for Ecotoxicity Research

| Resource Name | Primary Focus | Data Volume | Controlled Vocabulary System | Update Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | Ecological toxicity data | >12,000 chemicals, >1 million test results | EPA-specific taxonomy; standardized test parameters | Quarterly |

| ADORE Dataset | Acute aquatic toxicity ML benchmarking | 3 taxonomic groups; chemical & species features | Taxonomic classification; chemical identifiers | Specific versions |

| MEDLINE/PubMed | Biomedical literature | >26 million citations | Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | Continuous |

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | Chemical properties and toxicity | >350,000 chemicals | DSSTox Substance ID (DTXSID) | Regular updates |

Table 2: Common Controlled Vocabulary Systems in Scientific Databases

| Vocabulary System | Database Application | Scope and Coverage | Specialized Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | PubMed/MEDLINE | Hierarchical vocabulary for medical concepts | Automatic term mapping and explosion |

| Emtree | Embase | Biomedical and pharmacological terms | Drug and disease terminology |

| CINAHL Headings | CINAHL | Nursing and allied health | Intervention and assessment terms |

| EPA Taxonomy | ECOTOX Database | Ecotoxicology test parameters | Species, endpoints, experimental conditions |

Protocols for Systematic Literature Review and Data Curation

Systematic Review Workflow for Ecotoxicity Literature

Systematic reviews in ecotoxicology employ transparent, objective methodologies to identify, evaluate, and synthesize evidence from multiple studies. The process involves five critical steps that ensure comprehensive coverage and minimize bias [16] [17].

Systematic Review Workflow Diagram

Step 1: Framing the Research Question

A well-structured research question is the foundation of any systematic review. For ecotoxicity studies, this typically follows the PICOT framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Time) to define scope and key elements [16] [18]. The question should meet FINER criteria (Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant) to ensure practical and scientific value [18]. For example, in assessing chemical safety, a structured question would specify: the test species (population), chemical exposure (intervention), control groups (comparison), measured endpoints like LC50 (outcome), and exposure duration (time) [16] [7].

Step 2: Identifying Relevant Literature

Comprehensive literature search requires multiple strategies to capture all relevant studies. Best practices include:

- Search multiple databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central, and specialized resources like ECOTOX [16] [18] [4]

- Combine controlled vocabulary and keywords to account for terminology variations [19]

- Implement citation tracking by examining references of relevant articles [18]

- Apply no language restrictions during initial search to minimize geographic bias [16]

For ecotoxicity research, specifically include specialized resources like the ECOTOX database, which employs systematic review procedures to curate toxicity data from published literature [4].

Step 3: Assessing Study Quality

Quality assessment evaluates potential biases and methodological robustness using established criteria [16]:

- Study design appropriateness for research question (e.g., randomized vs. observational)

- Exposure ascertainment accuracy and timing relative to intervention

- Outcome measurement validity, including blinding and follow-up duration

- Control of confounding factors through design or statistical adjustment

In ecotoxicology, the Klimisch score or similar systems categorize studies based on reliability, with high-quality studies providing definitive data for risk assessment [4].

Step 4: Summarizing the Evidence

Data synthesis involves extracting and combining results from included studies. Create standardized tables documenting:

- Study characteristics (author, year, design)

- Test organisms and chemical details

- Exposure conditions and durations

- Measured endpoints and effect values

- Statistical analyses and results

Synthesis can be narrative (descriptive summary) or quantitative (meta-analysis), depending on study homogeneity [16].

Step 5: Interpreting the Findings

Interpret results by considering quality assessments, potential biases, heterogeneity sources, and overall evidence strength. Evaluate publication bias and address implications for risk assessment and future research [16].

Data Curation Pipeline for Ecotoxicity Studies

Effective data curation ensures ecological toxicity data remain accessible and reusable for future applications. The CURATE(D) model provides a structured approach [20]:

Data Curation Pipeline Diagram

Check Files and Documentation

- Verify completeness of data transfer, especially for large datasets [21]

- Conduct file inventory to ensure all components are present

- Appraise and select appropriate files for curation and publication

Understand the Data

- Execute code/scripts to verify functionality and outputs [21]

- Perform quality control through calibration, validation, and normalization

- Review README files and documentation for completeness

Request Missing Information

- Identify data gaps requiring researcher clarification

- Track provenance of all changes and additions

- Establish communication with data creators for context clarification

Augment Metadata for Findability

- Assign persistent identifiers (DOIs) for dataset citation [21]

- Apply standardized metadata schemas appropriate for ecotoxicology

- Enhance discoverability through controlled vocabulary terms

Transform File Formats for Reuse

- Convert to open, non-proprietary formats (e.g., CSV instead of Excel) [21]

- Ensure long-term accessibility while preserving data integrity

- Consider publishing both raw and curated data when scientifically valuable

Evaluate for FAIRness

- Assess interoperability with related resources and tools

- Verify accessibility through appropriate licensing and access controls

- Ensure reusability through comprehensive documentation

Document All Curation Activities

- Maintain detailed records of all curation decisions and modifications

- Explain quality control methods applied to the data [21]

- Provide context for future users to understand data transformations

Implementation Example: The ECOTOX Database Pipeline

The ECOTOX database exemplifies a mature literature review and data curation pipeline for ecotoxicity data. Its systematic approach includes:

Literature Search and Acquisition

- Comprehensive source monitoring of over 1,200 scientific journals [4]

- Structured search strategies using controlled vocabulary and keywords

- Regular quarterly updates to incorporate new data

Data Extraction and Curation

- Systematic review procedures following documented guidelines [4]

- Structured data extraction using controlled vocabularies for:

- Test organisms (species, taxonomy, life stage)

- Chemical identifiers (CAS, DTXSID, InChIKey, SMILES)

- Experimental conditions (duration, endpoints, media)

- Results (effect values, statistical measures)

- Quality control through expert review and validation

Controlled Vocabulary Application

ECOTOX employs extensive controlled vocabularies to standardize:

- Taxonomic classification using standardized nomenclature

- Chemical identification with multiple identifier systems

- Endpoint categorization (e.g., LC50, EC50, NOEC)

- Effect types (mortality, growth, reproduction, etc.)

- Test media and conditions (freshwater, seawater, sediment)

This standardized approach enables interoperability with other resources like the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard and supports computational toxicology applications [4].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ecotoxicity Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Databases | ECOTOX Knowledgebase, EnviroTox | Curated toxicity data for hazard assessment | Standardized test results; Quality-controlled data |

| Chemical Identification | CAS RN, DTXSID, InChIKey, SMILES | Unique chemical identifiers for tracking | Cross-database compatibility; Structural information |

| Benchmark Datasets | ADORE Dataset | Machine learning training and validation | Multiple taxonomic groups; Chemical and species features |

| Controlled Vocabularies | MeSH, Emtree, EPA Taxonomy | Standardized terminology for data retrieval | Hierarchical structure; Comprehensive coverage |

| Statistical Software | R, Python with pandas | Data analysis and modeling | Reproducible workflows; Extensive package ecosystems |

| Molecular Representations | SMILES, Molecular fingerprints | Chemical structure encoding for QSAR | Machine-readable formats; Structure-activity relationships |

Experimental Protocol: Building a Curated Ecotoxicity Dataset

Protocol: Developing a Benchmark Dataset for Machine Learning

Experimental Aim

To create a comprehensive, curated dataset of acute aquatic toxicity values for machine learning applications, incorporating chemical, species, and experimental data with controlled vocabulary standards [7].

- Source Data: ECOTOX database (latest release)

- Taxonomic Coverage: Fish, crustaceans, algae

- Chemical Identifiers: CAS RN, DTXSID, InChIKey, SMILES

- Programming Tools: Python or R for data processing

- Metadata Standards: Domain-specific controlled vocabularies

Procedure

Data Acquisition and Filtering

- Download ECOTOX core tables (species, tests, results, media)

- Filter entries for target taxonomic groups (fish, crustaceans, algae)

- Select relevant endpoints (LC50, EC50) and exposure durations (48-96 hours)

- Exclude in vitro tests and embryo-life stage tests [7]

Data Harmonization

- Standardize chemical identifiers using CAS RN, DTXSID, and InChIKey

- Apply taxonomic classification using controlled vocabulary

- Normalize effect values and units (convert to molar concentrations)

- Categorize test media and conditions using standardized terms

Feature Expansion

- Add chemical descriptors (molecular weight, log P, functional groups)

- Incorporate species traits (phylogenetic information, habitat preferences)

- Include experimental conditions (temperature, pH, water hardness)

- Generate molecular representations (SMILES, fingerprints)

Quality Control and Validation

- Implement outlier detection for extreme values

- Verify chemical structure-identifier consistency

- Cross-reference with other sources for data validation

- Apply completeness assessment for critical fields

Dataset Splitting and Documentation

- Create predefined train-test splits based on chemical scaffolds

- Develop comprehensive data dictionaries explaining all fields

- Document all processing steps and decision rules

- Publish in open, accessible formats with usage licenses

Expected Results

A standardized benchmark dataset (such as ADORE) containing:

- Core ecotoxicity measurements (LC50/EC50 values)

- Chemical characteristics and molecular representations

- Species information and phylogenetic context

- Experimental conditions and methodological details

- Predefined splits for model validation and comparison

This protocol supports the development of robust QSAR and machine learning models while ensuring FAIR data principles through comprehensive curation and controlled vocabulary application [7].

In ecotoxicology, the integration of data from diverse sources—including guideline studies and the open literature—is fundamental for robust ecological risk assessments (ERAs) [13]. However, the primary source language describing treatment-related endpoints is highly variable, creating significant barriers to data comparison, integration, and reuse [1]. A controlled vocabulary provides the solution: an authoritative set of standardized terms selected and defined to ensure consistent indexing and description of data [22]. Implementing such a vocabulary is essential for creating a findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) dataset, which in turn is critical for regulatory decision-making, chemical prioritization, and the validation of predictive models [1] [9]. This document outlines the key components and protocols for building a controlled vocabulary for ecotoxicity data, providing a framework to enhance the consistency and transparency of ERA.

Core Components of an Ecotoxicity Controlled Vocabulary

A comprehensive controlled vocabulary for ecotoxicity data is built upon four foundational pillars. Standardizing these elements ensures that data from different studies can be systematically aggregated, queried, and interpreted.

Chemical Substance Identification

Unambiguous chemical identification is the cornerstone of any ecotoxicological database. Inconsistent naming (e.g., using trade names vs. systematic names) severely hampers data retrieval and integration.

- Structured Identifiers: Each chemical should be associated with unique identifiers from authoritative sources. The EPA's CompTox Chemicals Dashboard provides such identifiers, including DSSTox Substance Identifiers (DTXSID), which are crucial for linking chemical records across databases [6].

- Standardized Naming: The preferred chemical name should be consistent with international nomenclature standards (e.g., IUPAC). Synonyms and common names should be cataloged but linked to the primary identifier to ensure comprehensive searchability.

Test Species and Organism Profile

The test organism must be identified with sufficient taxonomic precision to allow for meaningful interspecies comparisons and extrapolations.

- Taxonomic Resolution: Species should be identified by their full binomial name (genus and species), and verified using authoritative taxonomic references [13] [23]. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Taxonomy Database provides unique taxonomy IDs that can be used for standardization [24].

- Life Stage and Source: The controlled vocabulary must include terms for life stage (e.g., neonate, juvenile, adult) and the source of the organisms (e.g., laboratory culture, field-collected), as these factors can significantly influence toxicity outcomes [23].

Ecotoxicological Endpoints

The biological effects measured in a study must be described using consistent terminology to enable cross-study analysis and meta-analysis.

- Endpoint Harmonization: Primary source language (e.g., "mortality," "death," "% dead") should be mapped to a single controlled term. Existing vocabularies such as the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS), OECD harmonized templates, and the BfR DevTox lexicon provide a strong foundation for describing prenatal developmental and other toxicological endpoints [1].

- Temporal and Statistical Descriptors: The vocabulary must include standardized terms for the effect measurement (e.g., EC50, LC50, NOEC, LOEC) and the exposure duration (e.g., 24-h, 48-h, 96-h, chronic) [13] [25]. This allows for clear differentiation between, for example, an acute 48-h LC50 and a chronic 28-day NOEC.

Test Conditions and Methodology

Detailed and standardized reporting of test conditions is necessary to evaluate the reliability and relevance of a study and to understand the context of the reported effects.

- Exposure System: Terms should describe the test location (laboratory vs. field), route of exposure (water, sediment, diet), and test system type (static, renewal, flow-through) [13] [26].

- Environmental Parameters: Key parameters such as water temperature, pH, hardness, and light regime must be included, as they can modulate chemical toxicity [23]. The vocabulary should standardize the units and measurement methods where possible.

Table 1: Core Components of an Ecotoxicity Controlled Vocabulary

| Component | Description | Standardization Source Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Identity | Unique substance identification | CompTox Chemicals Dashboard (DTXSID), CAS RN [6] |

| Test Species | Taxonomic identity of organism | NCBI Taxonomy ID, Verified binomial name [24] |

| Ecotoxicological Endpoint | Measured biological effect | UMLS, OECD Templates, BfR DevTox Terms [1] |

| Test Conditions | Methodology & environment | CRED reporting criteria, EPA Evaluation Guidelines [13] [27] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Controlled Vocabulary for Data Integration

The following protocol describes a systematic approach for standardizing extracted ecotoxicity data using an augmented intelligence workflow, which combines automated mapping with expert manual review [1].

Protocol: Automated and Manual Vocabulary Mapping

Objective: To standardize raw endpoint descriptions from ecotoxicity studies into controlled terms, enabling the creation of a FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) dataset.

Materials and Reagents:

- Hardware: Standard computer workstation.

- Software: Python scripting environment (e.g., version 3.7 or higher) [1].

- Data Input: A dataset of ecotoxicity test results with endpoint descriptions recorded in the primary source language (e.g., from ECOTOX Knowledgebase, ECHA dossiers, or NTP reports) [1] [9].

- Key Resource - Controlled Vocabulary Crosswalk: A harmonized crosswalk file linking common endpoint descriptions to standardized terms from UMLS, OECD templates, and BfR DevTox [1].

Procedure:

- Data Extraction and Preparation: Assemble the legacy or newly extracted ecotoxicity data. Ensure the data on chemicals, species, endpoints, and test conditions are in a structured format (e.g., a spreadsheet or database table).

- Automated Mapping Execution: Run the pre-developed annotation code (e.g., Python script) designed to automatically match the primary source endpoint descriptions to the standardized terms in the controlled vocabulary crosswalk [1].

- Categorization of Mapped Data: Upon completion of the automated script, the data will be separated into two streams:

- Stream A: Automatically Mapped. Endpoints for which the script found a direct and confident match in the crosswalk.

- Stream B: Unmapped. Endpoints that were too general, ambiguous, or lacked a direct lexical match for automated mapping.

- Manual Review and Curation:

- For Stream A, perform a quality control check on a subset of the automated mappings to identify potential extraneous matches or inaccuracies. It is estimated that about half of the automatically mapped terms may require this verification [1].

- For Stream B, trained risk assessors or data curators must manually assign the appropriate controlled vocabulary terms using professional judgment and logic. This step is critical for complex or nuanced endpoint descriptions.

- Data Integration and Documentation: Merge the validated mapped data from Stream A and the manually curated data from Stream B into a final, standardized dataset. Document the entire process, including the version of the crosswalk used, the mapping script, and any manual decisions made, to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this integrated process:

Successful implementation of a controlled vocabulary and the execution of high-quality ecotoxicity tests rely on specific, well-characterized materials and databases.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Ecotoxicity Data Generation and Curation

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Application in Ecotoxicity |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Toxicant [23] | A standard chemical used to assess the sensitivity and performance consistency of a test organism batch. | Quality control; verifying organism health and test system reliability. |

| Certified Test Organisms [23] | Organisms of a known species, age, and life stage, sourced from reliable culture facilities. | Ensures test reproducibility and validity; required for guideline studies. |

| EPA ECOTOX Knowledgebase [9] | A comprehensive, publicly available database of single-chemical ecotoxicity effects. | Primary source for curated data; template for vocabulary structure. |

| Controlled Vocabulary Crosswalk [1] | A file mapping common terms to standardized vocabularies (UMLS, OECD, BfR). | Core resource for automating data standardization efforts. |

| CRED Evaluation Method [27] | A framework of criteria for evaluating the reliability and relevance of ecotoxicity studies. | Provides structured guidance for manual review and study inclusion. |

The construction and implementation of a controlled vocabulary for the key components of ecotoxicity data are not merely an administrative exercise but a scientific necessity. By standardizing the language used to describe chemicals, species, endpoints, and test conditions, the ecotoxicology community can overcome significant barriers to data interoperability. The protocols and tools outlined herein provide a actionable path toward creating robust, FAIR datasets. This, in turn, enhances the reliability of ecological risk assessments, supports the development of predictive models, and ultimately informs better decision-making for the protection of environmental health.

In the domain of ecotoxicity data research, ensuring consistent terminology is paramount for data interoperability, systematic reviews, and computational toxicology. Controlled vocabularies (CVs) are organized arrangements of words and phrases used to index content and retrieve it through browsing or searching [28]. They provide a common understanding of terms, reduce ambiguity, and are essential for making data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) [1]. The Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) is a World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) standard designed for representing such knowledge organization systems—including thesauri, classification schemes, and taxonomies—as machine-readable data using the Resource Description Framework (RDF) [29] [30] [31]. By encoding vocabularies in SKOS, concepts and their relationships become processable by computers, enabling decentralized metadata applications and facilitating the integration of data harvested from multiple, distributed sources [29] [32].

SKOS Core Components and Data Model

The SKOS data model is concept-centric, where the fundamental unit is an abstract idea or meaning, distinct from the terms used to label it [30] [33]. This model provides a standardized set of RDF properties and classes to describe these concepts and their interrelations.

Fundamental SKOS Constructs

- Concepts and Concept Schemes: A

skos:Conceptrepresents an idea or meaning within a knowledge organization system. Each concept is identified by a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI), making it a unique, web-accessible resource [33] [31]. Concepts are typically aggregated into askos:ConceptScheme, which represents a complete controlled vocabulary, thesaurus, or taxonomy [30]. - Lexical Labels: Concepts are labeled using human-readable strings. SKOS defines three primary labeling properties:

skos:prefLabel(Preferred Label): The primary, authoritative name for a concept. A concept can have at most oneprefLabelper language tag [30] [28].skos:altLabel(Alternative Label): Synonyms, acronyms, or other variant terms for the concept. A concept can have multiplealtLabels [30] [28].skos:hiddenLabel: A variant string that is useful for text indexing and search but is not intended for display to end-users (e.g., common misspellings) [30].

- Documentation Properties: SKOS offers several properties to document concepts, all of which are sub-properties of

skos:note. These includeskos:definitionfor formal explanations,skos:scopeNotefor information about the term's intended usage, andskos:exampleto illustrate application [30] [31]. - Semantic Relations: Concepts are interlinked through semantic relationships.

- Hierarchical Relations:

skos:broaderandskos:narrowerlink a concept to others that are more general or specific, respectively. While not defined as transitive in the core model, SKOS also providesskos:broaderTransitiveandskos:narrowerTransitivefor inferring transitive closures [30] [28]. - Associative Relations:

skos:relatedlinks two concepts that are associatively related but not in a hierarchical fashion [30] [31].

- Hierarchical Relations:

- Mapping Properties: For interoperability between different concept schemes, SKOS provides mapping properties like

skos:exactMatch,skos:closeMatch,skos:broadMatch, andskos:narrowMatch. These are used to declare mapping links between concepts in different vocabularies [30] [33].

Visualizing the SKOS Data Model

The following diagram illustrates the core structure and relationships within a SKOS-concept scheme, providing a visual representation of the components described above.

Implementation Protocols for Ecotoxicity Data

Implementing SKOS for standardizing ecotoxicity data involves a structured process from vocabulary selection to automated application. The following workflow outlines the key stages in this process.

Protocol 1: SKOS Vocabulary Development and Mapping Workflow

Detailed Methodological Steps:

- Extract Toxicological End Points: Begin by extracting treatment-related end points from primary study reports, legacy datasets, and database records. The original language used in the source documents should be recorded verbatim [1].

- Analyze Source Language Variability: Catalog the variation in terminology used to describe identical or similar end points. This analysis highlights the requirement for standardization to enable cross-study comparison and integration [1].

- Select Authority Vocabularies: Identify and select established, domain-specific controlled vocabularies to serve as the target for standardization. In ecotoxicity and developmental toxicology, relevant vocabularies often include:

- Unified Medical Language System (UMLS): A compendium of many controlled vocabularies in the biomedical sciences, providing comprehensive coverage of clinical and biological terms [1].

- BfR DevTox Database Lexicon: A harmonized set of terms specifically developed for application to developmental toxicity data [1].

- OECD Harmonised Templates: Standardized terminology for reporting chemical test results [1].

- Build a Controlled Vocabulary Crosswalk: Create a crosswalk that maps terms from the selected authority vocabularies to each other and, where possible, to common phrases found in the extracted source data. A crosswalk is a structured document (e.g., a spreadsheet or RDF using

skos:closeMatch/skos:exactMatch) that annotates the overlaps between different vocabularies [1]. This resource acts as a translation layer between source terms and standardized SKOS concepts. - Automated SKOS Mapping: Develop and execute annotation code (e.g., in Python) to automatically process the extracted end points and map them to standardized SKOS concepts using the pre-defined crosswalk. This code typically employs string matching, lookup tables, and simple logic to assign the appropriate URI of a SKOS concept to each extracted end point [1].

- Manual Review and Quality Control: Manually review a significant portion of the automatically mapped end points to identify and correct inaccuracies or extraneous matches. Research indicates approximately 51% of automatically mapped terms may require such manual review. End points that are too general or require complex human logic to match often remain unmapped by automated processes and must be handled separately [1].

- Publish as FAIR Linked Data: The finalized, standardized dataset should be published using RDF serialization formats (e.g., RDF/XML, Turtle). SKOS concepts are identified with persistent URIs, enabling them to be linked and dereferenced on the web. This final step ensures the data adheres to FAIR principles [1] [31].

Quantitative Performance of Automated SKOS Mapping

The table below summarizes performance metrics from a real-world implementation of an automated SKOS mapping approach in toxicology, demonstrating its efficiency gains.

Table 1: Performance Metrics from an Automated Vocabulary Mapping Exercise in Toxicology [1]

| Metric | NTP Extracted End Points | ECHA Extracted End Points |

|---|---|---|

| Total Extracted End Points | ~34,000 | ~6,400 |

| Automatically Standardized | 75% (~25,500 end points) | 57% (~3,650 end points) |

| Requiring Manual Review | ~13,005 end points (51% of standardized) | ~1,861 end points (51% of standardized) |

| Estimated Labor Savings | >350 hours | >350 hours |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential SKOS Research Reagents

Implementing SKOS-based solutions requires a combination of conceptual resources, software tools, and technical standards. The following table details key components of the SKOS research toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for SKOS Implementation

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| SKOS Core Vocabulary | Standard / Specification | The normative RDF vocabulary (classes & properties) for representing concept schemes, definitions, and semantic relations [32] [31]. |

| Controlled Vocabulary Crosswalk | Data Resource | A mapping table that links terms from different source vocabularies (e.g., UMLS, DevTox, OECD) to enable automated translation and standardization of extracted data [1]. |

| Annotation Code (e.g., Python Script) | Software Tool | Custom code that automates the application of the crosswalk to raw extracted data, matching source terms to standardized SKOS concept URIs [1]. |

| RDF Triplestore | Database System | A database designed for the storage, query, and retrieval of RDF triples. Essential for managing and querying large SKOS vocabularies and linked data [33]. |

| SPARQL Endpoint | Query Service | A protocol that allows querying RDF data using the SPARQL language. Enables complex queries over SKOS concepts and their relationships (e.g., finding all narrower terms) [31]. |

| UMLS Metathesaurus | Authority Vocabulary | A large, multi-source vocabulary in the biomedical domain that can be leveraged as a target for standardizing ecotoxicity terms [1]. |

| OECD Harmonised Templates | Authority Vocabulary | Standardized terminology for reporting chemical test results, providing authoritative terms for regulatory ecotoxicity data [1]. |

| Pendulone | Pendulone, MF:C17H16O6, MW:316.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Breviscapine | Breviscapine, MF:C21H18O12, MW:462.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The implementation of SKOS provides a robust, standards-based framework for transforming disparate and variably labeled ecotoxicity data into a machine-readable, interoperable resource. By following the detailed protocols for vocabulary mapping, automation, and quality control, researchers can achieve significant efficiencies in data curation. The resulting FAIR datasets, structured as linked data, become a powerful foundation for advanced computational toxicology, predictive modeling, and integrative meta-analyses, ultimately accelerating research and informing regulatory decisions.

In ecotoxicity data research, Controlled Vocabularies (CVs) are standardized sets of terms and definitions that enable consistent annotation, retrieval, and integration of complex environmental health data. The practical workflow for querying and retrieving data using these vocabularies is foundational to computational toxicology and chemical risk assessment. This protocol details the application of CVs within key public data resources, outlining a standardized methodology for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to efficiently access high-quality, structured ecotoxicity data. The framework is built primarily on tools and databases provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) CompTox initiative, which offers data freely for both commercial and non-commercial use [6].

The following tables summarize the core data resources that utilize controlled vocabularies for data query and retrieval. These resources provide the quantitative and qualitative data necessary for modern computational toxicology studies.

Table 1: Core Hazard and Exposure Data Resources

| Resource Name | Data Type | Key Content & Coverage | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ToxCast [6] | High-throughput screening | In vitro screening data for thousands of chemicals via automated assays. | Prioritization of chemicals for further testing; hazard identification. |

| ToxRefDB [6] | In vivo animal toxicity | Chronic, sub-chronic, developmental, and reproductive toxicity data from ~6,000 guideline studies on ~1,000 chemicals. | Anchoring high-throughput screening data to traditional toxicological outcomes. |

| ToxValDB [6] | Aggregated in vivo toxicology values | 237,804 records covering 39,669 unique chemicals from over 40 sources, including toxicity values and experimental results. | Risk assessment; derivation of point-of-departure and safe exposure levels. |

| ECOTOX [6] | Ecotoxicology | Adverse effects of single chemical stressors to aquatic and terrestrial species. | Ecological risk assessment. |

Table 2: Exposure, Chemistry, and Supporting Data Resources

| Resource Name | Data Type | Key Content & Coverage | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPDat [6] | Consumer product & use | Mapping of chemicals to their usage or function in consumer products. | Chemical exposure assessment from product use. |

| SHEDS-HT & SEEM [6] | High-throughput exposure | Rapid exposure and dose estimates to predict potential human exposure for thousands of chemicals. | High-throughput exposure modeling for chemical prioritization. |

| DSSTox [6] | Chemistry | Standardized chemical structures, identifiers, and physicochemical properties. | Chemical identification and structure-based querying. |

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [6] | Aggregation & Curation | A centralized portal providing access to chemistry, toxicity, and exposure data for ~900,000 chemicals. | Primary interface for chemical lookup, data integration, and download. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Query and Retrieval

This section provides detailed, step-by-step methodologies for executing key tasks within the researcher workflow, from chemical identification to advanced pathway analysis.

Protocol 1: Chemical Identification and List Assembly Using Controlled Vocabularies

Objective: To unambiguously identify a chemical of interest and its related substances (e.g., salts, hydrates) using standardized identifiers to assemble a target list for subsequent querying.

- Define Query Substance: Begin with a chemical name (e.g., "Bisphenol A"), CAS RN (e.g., "80-05-7"), or SMILES string.

- Access the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard: Navigate to the EPA's CompTox Chemicals Dashboard via its public URL.

- Perform Initial Search: Enter the query term into the main search bar. The Dashboard will resolve the query to a unique substance record using its internal controlled vocabulary (DSSTox Substance Identifier, or DTXSID).

- Identify Related Substances: On the resulting chemical summary page, locate the "Related Substances" list. This list, generated based on structural and registration rules, contains substances that are salts, hydrates, or other forms of the searched chemical. Note their DTXSIDs.

- Assemble Target List: Compile a list of all relevant DTXSIDs from the previous step. This list ensures that all relevant chemical forms are included in subsequent data queries, preventing data omission due to narrow identifier matching.

Protocol 2: Cross-Database Ecotoxicity Data Retrieval via Batch Query

Objective: To retrieve curated ecotoxicity data from the ECOTOX Knowledgebase for a pre-defined list of chemicals.

- Prepare Input File: Format your list of DTXSIDs (from Protocol 1) into a single-column text file.

- Access the ECOTOX Database: Navigate to the ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX) interface. It is recommended to use a web browser compatible with the tool (e.g., if experiencing issues in Chrome, clear cache or try an alternative browser) [6].

- Initiate Advanced Search: Select the "Advanced Search" option.