Bioavailability in Toxicity Testing: Bridging Exposure and Biological Effect for Accurate Risk Assessment

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role bioavailability plays in modern toxicity testing.

Bioavailability in Toxicity Testing: Bridging Exposure and Biological Effect for Accurate Risk Assessment

Abstract

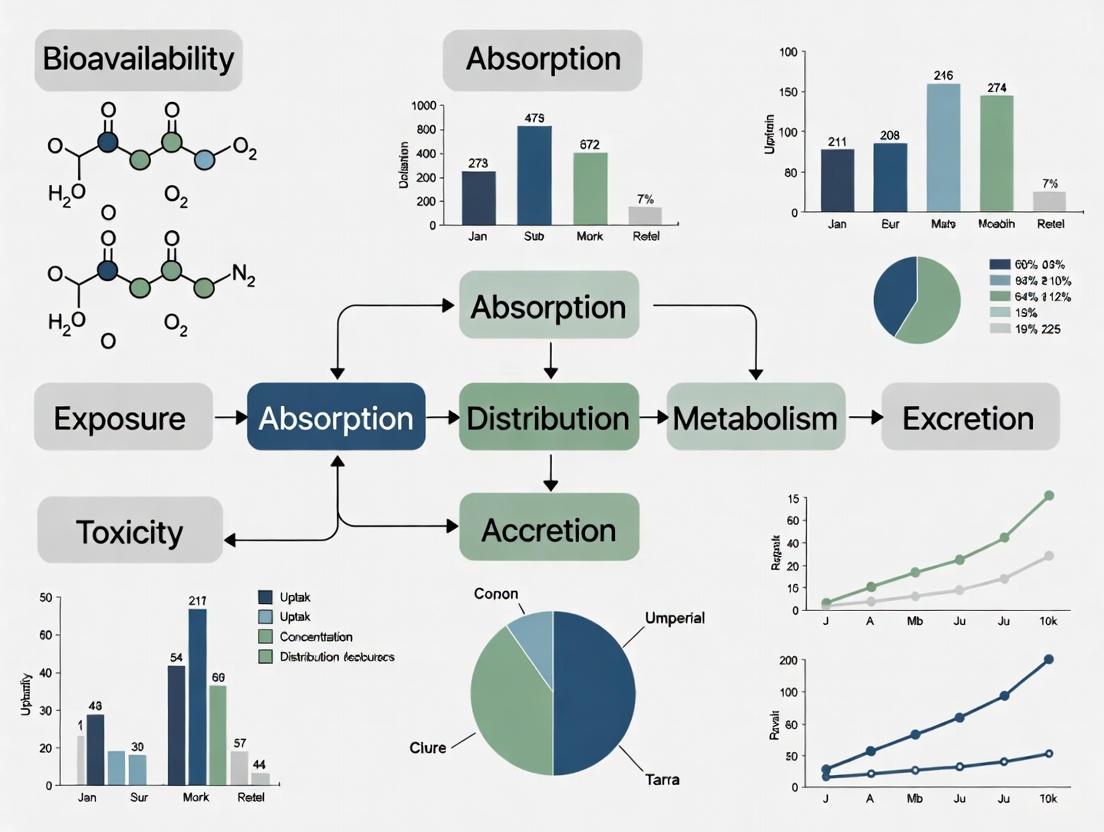

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role bioavailability plays in modern toxicity testing. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles defining bioavailability and its necessity for accurate hazard identification. The scope covers established and emerging methodologies for assessing bioavailability across chemical and nanoparticle exposures, strategies for troubleshooting common limitations, and the application of bioavailability data in regulatory bioequivalence and comparative toxicity evaluations. By synthesizing these elements, the article serves as a guide for integrating bioavailability considerations to enhance the predictive power, ethical rigor, and relevance of toxicological assessments.

Defining Bioavailability: The Critical Link Between Dose and Toxicological Effect

Core Concepts: Understanding Systemic Exposure and Site Action

What is the fundamental difference between systemic exposure and action at the site of action?

Systemic Exposure refers to the presence of a drug or compound in the systemic circulation (bloodstream), making it available throughout the body. It is typically measured by parameters such as the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) [1] [2]. In contrast, Action at the Site of Action refers to the drug's presence and interaction with its intended biological target (e.g., a receptor, enzyme, or tissue) to produce a pharmacological or toxicological effect [3]. For most drugs, the pharmacological response is related to its concentration at this receptor site [4].

Why is it crucial to distinguish between plasma concentration and concentration at the site of action in toxicity testing?

While plasma concentrations are a convenient and standard measurement, they may not always accurately reflect the drug levels at the actual site of action (e.g., a specific organ, a tumor, or the brain) [3]. Relying solely on plasma data can be misleading because:

- Distribution Barriers: Physiological barriers, like the blood-brain barrier, can prevent a drug from reaching its target organ in the same concentration found in the plasma [3].

- Local Metabolism: Tissues may metabolize drugs differently than what is observed systemically.

- Transporters: Uptake and efflux transporters can actively pump drugs into or out of specific tissues and cells, creating a concentration gradient that differs from plasma [3].

Consequently, understanding the drug concentration at the site of action provides a more accurate basis for assessing both efficacy and toxicity [3].

How is bioavailability defined, and what factors influence it?

Bioavailability (F) is defined as the fraction of an administered dose of a drug that reaches systemic circulation unaltered [1]. An intravenously administered drug has a bioavailability of 100%. For other routes, it is calculated by comparing the AUC for that route to the AUC for an IV dose of the same drug [1].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Bioavailability (ADME) [5]

| Factor | Description | Impact on Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Absorption | The process by which a drug enters the bloodstream from the site of administration (e.g., gut, muscle). | Affected by the drug's chemical properties, formulation, and route of administration. Low absorption reduces bioavailability. |

| Distribution | The reversible transfer of a drug from the bloodstream into tissues and organs. | A large volume of distribution may mean less drug is in the plasma, potentially reducing measurable systemic exposure for a given dose. |

| Metabolism | The chemical alteration of a drug by bodily systems, often into inactive metabolites. | Extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver or gut wall can significantly reduce the bioavailability of orally administered drugs. |

| Excretion | The removal of the drug and its metabolites from the body, primarily via kidneys or liver. | Rapid excretion can shorten the time a drug remains in systemic circulation and at the site of action. |

Additional factors include drug interactions, genetic polymorphisms in metabolizing enzymes or transporters, and pathophysiological conditions of the patient [1] [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Our in vitro assay shows high efficacy, but this doesn't translate in vivo. Could this be a bioavailability issue?

Yes, this is a common challenge. High in vitro efficacy indicates that the compound is active against its target when access is unimpeded. The discrepancy in vivo often arises because the compound may not be reaching the target site in sufficient concentrations. Key areas to investigate include:

- Poor Absorption: The compound may have low permeability or solubility in the gastrointestinal tract.

- High Clearance: The compound may be rapidly metabolized (e.g., by hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes) or excreted before it can distribute to the target tissue [1] [5].

- Efflux Transporters: Proteins like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) can actively pump the drug out of cells in the intestine or at the blood-brain barrier, limiting its absorption and tissue penetration [1] [3].

- Plasma Protein Binding: Only the unbound (free) fraction of a drug is pharmacologically active. High binding to plasma proteins like albumin can sequester the drug, reducing the amount available to diffuse into tissues [5].

FAQ 2: We are observing unexpected toxicity in a specific organ. How can we determine if it's due to localized drug accumulation?

Unexpected organ-specific toxicity can result from localized accumulation, where the drug reaches higher concentrations in a particular tissue than in the plasma. To investigate this:

- Measure Tissue Distribution: Conduct studies to directly measure drug concentrations in the affected organ versus plasma over time.

- Assess Tissue-Specific Transport: Investigate whether the organ expresses unique uptake transporters that actively concentrate the drug, or if it lacks efflux transporters that would remove it [3].

- Check for Local Metabolism: Determine if the organ metabolizes the drug into a toxic metabolite that is not formed systemically.

- Utilize PBPK Modeling: Use physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to simulate and predict drug distribution into specific tissues and identify potential accumulation hotspots [3] [6].

FAQ 3: Our bioanalytical results are highly variable. What are common sources of error in measuring drug and metabolite concentrations?

Variability in bioanalysis can stem from multiple sources in the sample preparation and analysis workflow:

- Matrix Effects: Components in the biological sample (plasma, tissue homogenate) can suppress or enhance the ionization of the analyte in techniques like LC-MS/MS, leading to inaccurate quantification [4].

- Incomplete Sample Preparation: Inefficient extraction of the drug and metabolites from the biological matrix, whether by protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, or solid-phase extraction, can cause low and variable recovery [4].

- Instability of Analytes: The drug or its metabolites may degrade during sample collection, storage, or processing if conditions (e.g., temperature, pH) are not properly controlled.

- Improper Internal Standard: Using an inappropriate internal standard that does not behave similarly to the analyte throughout the sample preparation and analysis can fail to correct for procedural variations [4].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Bioanalytical Methods

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in results | Inconsistent recovery, matrix effects, poor internal standard | Optimize extraction procedure, use a stable isotope-labeled internal standard, test for matrix effects via post-column infusion [4]. |

| Low analyte recovery | Inefficient extraction technique, analyte degradation | Re-evaluate extraction solvents and pH, ensure sample stability under processing conditions [4]. |

| Ion suppression in LC-MS/MS | Co-elution of matrix components with the analyte | Improve chromatographic separation to shift the analyte's retention time away from the "noise" region [4]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Assessing Bioavailability and Systemic Exposure

Objective: To determine the absolute bioavailability of a new chemical entity (NCE) administered orally.

Methodology:

- Study Design: A crossover or parallel-group study in a relevant animal model.

- Dosing: Administer the NCE orally (PO) and intravenously (IV) at the same dose level.

- Sample Collection: Collect serial blood samples (e.g., via cannulation) at predetermined time points after both administrations.

- Bioanalysis: Process plasma samples and quantify drug concentrations using a validated bioanalytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS) [4].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the AUC for both the PO and IV routes. Apply the formula for absolute bioavailability:

- F = (AUC~PO~ / Dose~PO~) / (AUC~IV~ / Dose~IV~) [1].

This protocol provides a direct measure of how much of the orally administered drug reaches the systemic circulation.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Drug Distribution to a Site of Action (e.g., Brain)

Objective: To evaluate the extent of drug penetration across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) into the brain.

Methodology:

- Dosing and Sampling: Administer the drug and collect paired plasma and brain tissue samples at multiple time points.

- Tissue Homogenization: Homogenize the brain tissue in a buffer.

- Drug Quantification: Analyze drug concentrations in both plasma and brain homogenate using a sensitive and specific method like LC-MS/MS [4].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the brain-to-plasma ratio (Kp) as:

- Kp = Total Drug Concentration in Brain / Total Drug Concentration in Plasma.

- For a more accurate assessment, measure the free (unbound) drug concentration in both matrices to calculate the unbound Kp (Kp,uu), which is more predictive of pharmacodynamic activity [3].

Diagram: Drug Distribution to Brain Site of Action

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Bioavailability and Distribution Studies

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | High-sensitivity analytical instrumentation for the quantitative determination of drugs and their metabolites in complex biological matrices like plasma, urine, and tissue homogenates [4]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Compounds used in bioanalysis to correct for variability and losses during sample preparation and analysis, improving accuracy and precision [4]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Used for sample clean-up and concentration of analytes from biological fluids, helping to reduce matrix effects prior to LC-MS/MS analysis [4]. |

| Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling Software | Computational tools that simulate the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of compounds in virtual populations, used to predict tissue exposure and extrapolate from in vitro to in vivo data [3] [6]. |

| In Vitro System for Transporter Assays | Cell-based systems (e.g., transfected cells) used to study the role of specific uptake or efflux transporters (e.g., P-gp, BCRP) on drug permeability and distribution [3]. |

| Metaflumizone-d4 | Metaflumizone-d4, MF:C24H16F6N4O2, MW:510.4 g/mol |

| 2-Deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose-13C | 2-Deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose-13C, MF:C6H11FO5, MW:183.14 g/mol |

Diagram: Predictive Workflow from In Vitro to In Vivo

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a chemical's hazard and its risk?

The hazard of a chemical is its inherent potential to cause harm, while the risk is the likelihood that such harm will occur under specific conditions of exposure [7]. A substance may be highly hazardous, but if there is no exposure, or exposure is below a harmful level, the risk is low or nonexistent. Toxicologists quantify this relationship as: Risk = Hazard x Exposure [7].

Q2: How does bioavailability connect hazard and risk in toxicity assessments?

Bioavailability acts as a critical modifier between hazard and risk. It measures the fraction of a substance that reaches systemic circulation and is available at the site of action [1]. A high-hazard substance with low bioavailability may present a lower risk because only a small amount of the ingested dose is actually absorbed and can cause toxic effects [8]. Therefore, accurate risk assessment must account for bioavailability, not just total contaminant concentration or inherent hazard [9].

Q3: What key pharmacokinetic parameters are used to quantify bioavailability?

Bioavailability (F) is quantitatively assessed using parameters derived from plasma concentration-time profiles [1]. The table below summarizes these key parameters:

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition & Significance in Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Bioavailability | F | The fraction of an administered drug that reaches the systemic circulation, compared to an intravenous (IV) dose (where F=100%) [10] [1]. |

| Area Under the Curve | AUC | The total integrated area under the plasma drug concentration-time curve. It represents the total exposure of the body to the drug over time and is directly proportional to the amount of drug absorbed [10] [1]. |

| Maximum Concentration | C~max~ | The peak plasma concentration of a drug after administration. It indicates the rate of absorption [11]. |

| Time to Maximum Concentration | T~max~ | The time it takes to reach C~max~ after drug administration. It is another indicator of the absorption rate [10]. |

Q4: How do nanoparticle carriers influence drug bioavailability and toxicity?

Nanoparticles (NPs) are used to improve the solubility and bioavailability of poorly absorbed compounds like resveratrol [11]. However, the nanocarriers themselves can introduce new toxicological considerations. A study on resveratrol-loaded nanoparticles found that the "empty" nanocarriers (without the active drug) sometimes induced higher mortality, DNA damage, and malformations than the drug-loaded nanoparticles [11]. This highlights that both the active ingredient and its delivery system must be evaluated for a complete safety assessment of nano-formulations [11].

Q5: What is the difference between bioaccessibility and bioavailability?

Bioaccessibility is the fraction of a substance that is dissolved in the gastrointestinal fluids and becomes potentially available for absorption. Bioavailability is the fraction that is actually absorbed and reaches the systemic circulation [8]. In vitro tests typically measure bioaccessibility, which can be used to predict in vivo bioavailability after proper calibration [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Low Bioavailability Readings in Animal Models

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Improper Study Design for Relative Bioavailability (RBA) Calculation.

- Solution: Ensure your experimental design includes the correct control groups. To calculate the Oral RBA of a test material (e.g., a lead particle), you must include groups that receive the same substance in a soluble reference form (e.g., lead acetate), both orally and intravenously (IV). The IV group is used to determine the Absolute Bioavailability (ABA) of the reference material [8]. The RBA of the test material is then calculated using the formula:

RBA = (Internal Dose Metric from oral test material / Internal Dose Metric from oral reference) x (Dose of oral reference / Dose of oral test material)[8]. - Protocol: Administer similar dose ranges of the test material and the reference material to ensure the dose-response curves are comparable. Use low to high doses to capture potential saturation in absorption [8].

- Solution: Ensure your experimental design includes the correct control groups. To calculate the Oral RBA of a test material (e.g., a lead particle), you must include groups that receive the same substance in a soluble reference form (e.g., lead acetate), both orally and intravenously (IV). The IV group is used to determine the Absolute Bioavailability (ABA) of the reference material [8]. The RBA of the test material is then calculated using the formula:

Cause 2: Overlooked Effects of the Test Formulation or Carrier.

- Solution: Always include a control group that is administered the "empty" formulation or carrier (e.g., the nanocarrier without the active compound). As demonstrated with Tween 80 and carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles, the carrier itself can cause toxicity, DNA damage, or estrogenic effects, which can confound the results for the active compound [11].

Cause 3: Unaccounted For Variability in Animal Gut Physiology.

- Solution: Be aware of life-span considerations. Gastric pH, intestinal absorption, and liver metabolism (first-pass effect) vary significantly in neonates and older animals compared to adults [12]. Choose an animal model whose digestive physiology best aligns with your research question and human population of interest.

Problem: High Uncertainty in Clinical Toxicology Data (e.g., Overdose Cases)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Missing or Unreliable Data on Dose and Timing.

- Solution: In clinical toxicology, the exact dose and time of ingestion are often unknown [13]. Implement Bayesian statistical approaches that treat the reported dose and time as random variables within defined bounds (e.g., provided by patient recall or first-responders). Use a veracity scale to weight the credibility of the patient's history, which is then incorporated into the prior distribution for dose estimation in pharmacokinetic models [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Oral Relative Bioavailability (RBA) in an Animal Model

This protocol outlines the key steps for assessing the RBA of a substance, such as a metal or a drug, in a particulate form.

1. Objective: To determine the Oral Relative Bioavailability of a test material (TM) relative to a soluble reference material (REF).

2. Materials:

- Test Animals: Young, fasted animals (species as appropriate for the test substance).

- Test Material (TM): The substance of interest (e.g., lead-contaminated soil, drug nanoparticles).

- Reference Material (REF): A soluble form of the active compound (e.g., lead acetate for lead studies).

- Dosing Solutions: Prepared at various concentrations in an appropriate vehicle.

- Equipment: Syringes, gavage needles, microcentrifuges, analytical instrument (e.g., ICP-MS, HPLC-MS) for quantifying the internal dose metric (e.g., blood lead level, plasma drug concentration).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Group Allocation. Randomly assign animals to the following groups:

- Group 1 (Control): Purified diet only.

- Group 2 (Oral REF): Receives the reference material orally at multiple dose levels.

- Group 3 (IV REF): Receives the reference material intravenously (to determine absolute bioavailability).

- Group 4 (Oral TM): Receives the test material orally at multiple dose levels.

- Step 2: Dosing. Administer the substances to the animals via the appropriate route. Ensure the dose ranges for the oral REF and oral TM groups are similar and cover from low to high concentrations.

- Step 3: Sample Collection. Collect blood samples at multiple time points post-administration according to a predetermined schedule to define the concentration-time curve.

- Step 4: Sample Analysis. Process and analyze the blood samples to determine the chosen Internal Dose Metric (IDM), such as the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of concentration vs. time or the concentration in a target organ.

- Step 5: Data Analysis and RBA Calculation. Calculate the RBA using the formula [8]:

RBA = (AUC oral TM / AUC oral REF) x (Dose oral REF / Dose oral TM)

Protocol 2: In Vitro Bioaccessibility Testing for Lead Particles

This protocol is used as a faster, cheaper screening tool to estimate the potential oral bioavailability of lead in particles, calibrated against in vivo data [8].

1. Objective: To estimate the bioaccessible fraction of lead in solid samples (e.g., soil, paint, dust) using a simulated gastrointestinal extraction.

2. Materials:

- Test Sample: Homogenized, sieved soil, dust, or other solid material.

- Gastric Solution: A solution simulating stomach fluid (e.g., containing pepsin, adjusted to low pH with HCl).

- Intestinal Solution: A solution simulating small intestine fluid (e.g., containing bile salts and pancreatin, adjusted to neutral pH).

- Incubator/Shaker.

- Centrifuge and Filters (e.g., 0.45 μm).

- Analytical Instrument: Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) or Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Gastric Phase. Weigh a sample into a extraction vessel. Add the gastric solution and incubate for 1 hour with continuous agitation, maintaining temperature at 37°C.

- Step 2: Intestinal Phase. After the gastric phase, adjust the pH of the mixture to the intestinal range and add the intestinal solution. Incubate for an additional 4 hours under the same conditions.

- Step 3: Separation. Centrifuge the final mixture and filter the supernatant.

- Step 4: Analysis. Analyze the filtered solution for lead concentration using ICP-OES/MS.

- Step 5: Calculation. Calculate the bioaccessible fraction as:

(Mass of Pb in extract / Total mass of Pb in the sample) x 100.

Visualizing the Concepts

Hazard vs Risk and Bioavailability

Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists essential materials used in bioavailability and toxicity testing, particularly for environmental and pharmaceutical research.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Carboxymethyl Chitosan (CMCS) | A polymer used as a nanocarrier to improve the solubility and delivery of poorly soluble drugs like resveratrol [11]. |

| Tween 80 | A nonionic surfactant used to stabilize nanoparticle dispersions and improve drug solubility [11]. |

| Lead Acetate (PbAc) | A readily soluble lead salt used as the reference material in in vivo experiments to determine the Relative Bioavailability (RBA) of lead from other sources (e.g., soil, paint) [8]. |

| Biochar | A carbon-rich material used in soil remediation to immobilize organic contaminants and heavy metals, thereby reducing their bioavailability and toxicity [9]. |

| Compost | An organic amendment used in soil remediation to stimulate microbial activity, enhancing the biodegradation of hydrocarbons and reducing the bioavailable fraction of contaminants [9]. |

| Activated Charcoal | Used in clinical toxicology as a decontamination agent. It adsorbs toxins in the GI tract, reducing their absorption (bioavailability) and the risk of systemic toxicity [13]. |

| N-Desmethyl Azelastine-d4-1 | N-Desmethyl Azelastine-d4-1, MF:C21H22ClN3O, MW:371.9 g/mol |

| Grp78-IN-2 | Grp78-IN-2|GRP78 Inhibitor|For Research Use |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

How do solubility, lipophilicity, and molecular size collectively influence bioavailability?

These three properties are interconnected pillars that determine a drug's journey from administration to systemic circulation.

- Solubility is the prerequisite for absorption. A drug must dissolve in the gastrointestinal (GI) fluids before it can cross the intestinal wall. Drugs with aqueous solubilities less than 100 µg/mL often present dissolution-limited absorption [14].

- Lipophilicity governs permeability. It determines how easily a dissolved drug molecule can cross lipid-based biological membranes to enter the bloodstream. An optimal lipophilicity (often represented as LogP between 1 and 3) is required to balance solubility and membrane permeability [15].

- Molecular Size affects diffusion rate. Smaller molecules (typically with a molecular weight ≤ 500 Da) generally diffuse more readily through membranes than larger, bulkier compounds [15].

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) leverages these properties to categorize drugs and predict absorption challenges [15]. A drug with poor solubility (BCS Class II or IV) will struggle to achieve sufficient concentration in the GI tract, while a drug with poor permeability (BCS Class III or IV) will have difficulty crossing the intestinal barrier.

What are the gold-standard methods for measuring these key properties?

The following table summarizes the standard experimental methods used to characterize these physicochemical drivers [16] [17] [14].

Table 1: Gold-Standard Methods for Assessing Key Physicochemical Properties

| Property | Key Measurement Methods | Typical Output | Significance for Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Shake-Flask Method: Equilibrium solubility determined by incubating a well-characterized solid form in a solvent (e.g., biorelevant buffer) for ~24 hours [17]. | Saturation solubility (Cs), often in µg/mL or mol·Lâ»Â¹. | Determines the maximum achievable concentration in GI fluids, driving dissolution [14]. |

| Lipophilicity | Shake-Flask Method: Partitioning between 1-octanol (modeling membranes) and a buffer (e.g., pH 7.4) is measured at equilibrium [16]. | Log P (for neutral compounds) or Log D (pH-dependent distribution coefficient). | Predicts membrane permeability and absorption potential; optimal LogP ~1-3 for oral drugs [15]. |

| Molecular Size | Calculated Descriptors: Derived from the molecular structure. | Molecular Weight (MW), Molecular Volume. | MW ≤ 500 Da is a common guideline for oral drugs; larger molecules have reduced passive diffusion [15]. |

My compound shows high solubility in the lab but low oral bioavailability in vivo. What could be the cause?

This common issue can arise from several factors beyond intrinsic solubility:

- Poor Metabolic Stability: The compound may be extensively metabolized by enzymes in the gut wall or liver during its "first-pass" metabolism, preventing it from reaching systemic circulation [10] [14].

- Efflux by Transporters: Active efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein can pump the drug back into the gut lumen after it has been absorbed into the intestinal cells [15].

- In Vivo Solubilization vs. Lab Conditions: The laboratory may use pure aqueous buffers, whereas the GI tract contains bile salts and phospholipids that form micelles. A compound might be soluble in buffer but precipitate in the gut if it does not remain solubilized within these micelles [14].

- Incorrect Solid Form: The solid form used in lab tests (e.g., an amorphous, high-energy form) might have higher solubility than the more stable crystalline form that precipitates in the GI environment [17].

Troubleshooting Checklist:

- Confirm the thermodynamic stability of the solid form used in your solubility assay.

- Assess metabolic stability in liver microsome or hepatocyte assays.

- Investigate potential for efflux using Caco-2 or transfected cell models.

- Measure solubility in fasted-state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF) or fed-state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF) to better mimic in vivo conditions [17].

How can I quickly diagnose the root cause of low solubility in a compound series?

A systematic "solubility diagnosis" can identify the primary molecular property responsible, guiding a targeted improvement strategy [17]. The following workflow helps pinpoint the issue:

What computational tools are available for early-stage prediction of these properties?

In silico tools are invaluable for prioritizing compounds before synthesis. SwissADME is a free, robust web tool that provides predictions for key ADME and physicochemical properties [18].

- Solubility: It uses topological methods to estimate aqueous solubility (Log S) [18].

- Lipophilicity: It offers a consensus Log P value by combining five different prediction models (iLOGP, XLOGP3, WLOGP, MLOGP, SILICOS-IT), improving accuracy [18].

- Molecular Size and Drug-likeness: It calculates molecular weight and other descriptors and features a Bioavailability Radar that provides a quick visual assessment of whether a compound's properties fall within the optimal space for oral bioavailability [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To determine the equilibrium solubility of a solid drug candidate in a pharmaceutically relevant medium.

Materials:

- Well-characterized drug substance (known solid form, e.g., crystalline)

- Biorelevant buffers (e.g., pH 2.0 for gastric conditions, pH 6.5 or 7.4 for intestinal conditions)

- Thermostated shaking water bath or incubator (set to 37°C)

- Centrifuge and centrifuge tubes (or filtration setup with compatible filters)

- Analytical instrument for quantification (e.g., HPLC-UV, LC-MS/MS)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Prepare a surplus of the solid drug substance. Pre-warm the selected buffer to 37°C.

- Saturation: Add an excess of the solid drug to a known volume of buffer in a sealed vial. The amount should ensure that undissolved solid remains at equilibrium.

- Equilibration: Place the vial in the shaking incubator at 37°C for a sufficient time to reach equilibrium (typically 24-48 hours). Shaking should be sufficient to ensure proper mixing.

- Phase Separation: After equilibration, separate the saturated solution from the undissolved solid. This is critical and can be done by:

- Centrifugation: At 37°C to prevent precipitation due to temperature change.

- Filtration: Using a pre-warmed syringe and a filter that does not adsorb the drug.

- Quantification: Dilute the clear supernatant appropriately and analyze using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV) to determine the drug concentration.

- Analysis: Calculate the saturation solubility (Cs) from the measured concentration, typically reported in µg/mL or µM.

Objective: To measure the partition coefficient of a drug between 1-octanol and a buffer, simulating its distribution between lipid membranes and aqueous physiological fluids.

Materials:

- High-purity 1-octanol (pre-saturated with buffer)

- Buffer solution (e.g., phosphate buffer pH 7.4, pre-saturated with 1-octanol)

- Thermostated shaking water bath (set to a constant temperature, e.g., 25°C or 37°C)

- Centrifuge and centrifuge tubes

- Analytical instrument for quantification (e.g., HPLC-UV)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Pre-saturate 1-octanol and buffer by mixing them together vigorously for 24 hours and allowing them to separate. Use the respective saturated phases for the experiment.

- Partitioning: Place known volumes of the octanol-saturated buffer and buffer-saturated octanol in a vial. Add a known amount of the drug compound.

- Equilibration: Seal the vial and agitate vigorously in a shaking water bath at a constant temperature for a set period (e.g., 1 hour) to reach partitioning equilibrium.

- Separation: Transfer the mixture to a centrifuge tube and centrifuge to achieve a clean separation of the two phases.

- Sampling: Carefully sample from each phase, ensuring no cross-contamination.

- Quantification: Dilute the samples as necessary and analyze the drug concentration in both the aqueous and octanol phases using HPLC-UV.

- Calculation: Calculate the partition coefficient P using the formula:

- P = [Drug]â‚’câ‚œâ‚ₙₒₗ / [Drug]ᵦᵤᶠᶠᵉᵣ

- Log P = logâ‚â‚€ (P)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Bioavailability-Related Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Biorelevant Buffers | Simulate the pH and ionic strength of different GI regions (stomach, small intestine) for dissolution and solubility testing. | HCl buffer (pH 2.0), Phosphate buffers (pH 6.5, 7.4) [16]. |

| Simulated Intestinal Fluids | More advanced media containing bile salts and phospholipids to mimic the solubilizing capacity of intestinal fluids. | FaSSIF (Fasted State), FeSSIF (Fed State) [17]. |

| 1-Octanol | A model solvent for the lipid portion of biological membranes used in partition coefficient studies. | High-purity grade, pre-saturated with the aqueous buffer of choice [16]. |

| In Vitro Permeability Models | Cell-based systems used to predict intestinal absorption and efflux. | Caco-2 cell line (human colon adenocarcinoma) [15]. |

| Chromatography Columns | For analytical quantification of drug concentrations in complex samples like solubility and partition experiments. | Reversed-phase C18 columns for HPLC/LC-MS [19]. |

| In Silico Prediction Tools | Free web-based software for predicting ADME and physicochemical properties from molecular structure. | SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch) [18]. |

| 15-Acetyl-deoxynivalenol-13C17 | 15-Acetyl-deoxynivalenol-13C17, MF:C17H22O7, MW:355.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cbl-b-IN-2 | Cbl-b-IN-2 |

Core Concepts and Key Mechanisms

This section outlines the fundamental processes that govern a compound's journey from administration to reaching its site of action, which are critical for interpreting bioavailability in toxicity testing.

What are the primary mechanisms of drug absorption?

After administration, a compound must cross biological membranes to enter the systemic circulation. This occurs primarily through three mechanisms [20]:

- Passive Diffusion: The most common mechanism, where molecules move from a region of higher concentration to one of lower concentration. Lipophilic drugs typically cross membranes via lipid diffusion, governed by their lipid-aqueous partition coefficient.

- Carrier-Mediated Membrane Transport: This includes active transport (energy-dependent, can move against concentration gradients) and facilitated diffusion (carrier-mediated but follows concentration gradients). Examples include peptide transporters (PEPT1) and organic cation transporters (OCT1) [21].

- Paracellular Pathway: Small hydrophilic molecules can pass through gaps between cells via passive diffusion, although tight junctions often limit this route [22].

What is the first-pass effect and how does it reduce bioavailability?

The first-pass effect describes metabolism that occurs before a drug reaches the systemic circulation, predominantly after oral administration [23].

- Process: Orally administered drugs are absorbed from the GI tract and enter the hepatic portal vein, which carries them directly to the liver. The liver (and sometimes the gut wall) then metabolizes a significant portion of the drug before it can reach the general bloodstream [23].

- Impact: This pre-systemic metabolism substantially reduces the oral bioavailability of many drugs, meaning a smaller fraction of the administered dose becomes systemically available. Drugs like morphine, lidocaine, and glyceryl trinitrate undergo significant first-pass metabolism [23].

How do efflux transporters limit drug bioavailability?

Efflux transporters are ATP-dependent pumps that actively transport compounds back out of cells, limiting their absorption and distribution. The most well-characterized is P-glycoprotein (P-gp) [22] [20].

- Location and Function: P-gp is present in the intestinal epithelium, liver, kidney, and blood-brain barrier. In the gut, it pumps absorbed drugs back into the intestinal lumen, effectively reducing net absorption [21].

- Clinical Significance: P-gp can act as a "gatekeeper," working in concert with metabolizing enzymes like CYP3A4 to control drug access. Inhibition or induction of P-gp can lead to significant drug-drug interactions [23].

Table 1: Key Biological Barriers and Their Impact on Bioavailability

| Barrier / Mechanism | Primary Location | Impact on Bioavailability | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Epithelium | Gastrointestinal Tract | Limits oral absorption | Molecular size, lipophilicity, efflux transporters (P-gp), gut wall metabolism [20] [24] |

| First-Pass Metabolism | Liver, Gut Wall | Pre-systemic inactivation of drug | Hepatic extraction ratio, intestinal enzyme activity [23] |

| Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) | Capillaries in CNS | Protects brain from xenobiotics | Tight junctions, efflux transporters (P-gp, BCRP), passive permeability [22] [25] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is our compound showing low oral bioavailability in in vivo models despite good solubility?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Significant First-Pass Metabolism. The compound may be extensively metabolized by the liver or gut wall before entering systemic circulation [23].

- Investigation Strategy:

- Compare plasma levels after intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration. A much higher AUC (Area Under the Curve) after IV administration confirms a first-pass effect.

- Conduct in vitro metabolism studies using liver microsomes or hepatocytes to assess metabolic stability.

- Potential Solutions:

- Consider alternative routes of administration (e.g., sublingual, transdermal) that bypass first-pass metabolism [23].

- Explore chemical modification to create a prodrug that is less susceptible to first-pass metabolism.

- Investigation Strategy:

Cause 2: Activity of Efflux Transporters. Transporters like P-gp may be actively pumping the compound back into the gut lumen [20] [21].

- Investigation Strategy:

- Use Caco-2 cell monolayers to assess transport. A higher efflux ratio (Basolateral-to-Apical / Apical-to-Basolateral) suggests active efflux.

- Perform transport assays with and without specific P-gp inhibitors (e.g., verapamil, zosuquidar).

- Potential Solutions:

- Formulate the drug with efflux transporter inhibitors (though this requires careful consideration of drug-drug interactions).

- Chemically modify the compound to make it a poorer substrate for the efflux transporter.

- Investigation Strategy:

FAQ 2: How can we improve the predictive power of our in vitro models for blood-brain barrier penetration?

Challenges and Methodological Refinements:

- Standard In Vitro Models Lack Complexity: Simple cell monolayers (e.g., Caco-2) may not fully replicate the BBB's tight junctions and diverse transporter expression [22] [26].

- Enhanced Protocol:

- Utilize specialized brain endothelial cell lines (e.g., hCMEC/D3) or primary cells that better express BBB-specific markers.

- Measure and ensure a high Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) to confirm the integrity of tight junctions.

- Include validated markers for paracellular (e.g., lucifer yellow) and transcellular permeability.

- Incorporate Transport Studies: Assess the compound's permeability in both directions (A-to-B and B-to-A) to identify efflux transporter substrates. Use chemical inhibitors to pinpoint specific transporters involved (e.g., P-gp, BCRP) [25].

- Enhanced Protocol:

FAQ 3: Our experimental results are highly variable between assays. How can we standardize bioavailability assessment?

Strategies for Standardization:

- Characterize and Control Assay Conditions: Variability often stems from inconsistent experimental conditions [22].

- Detailed Protocol for Cell-Based Permeability Assays:

- Cell Culture: Use low-passage number cells and ensure full monolayer differentiation. For Caco-2 cells, this typically takes 21-25 days.

- Validation: Before each experiment, measure TEER and the permeability of control compounds (e.g., high-permeability metoprolol, low-permeability atenolol).

- Dosing Solution: Use fasted-state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF) or fed-state (FeSSIF) to better mimic physiological conditions, as food can affect solubility and transporter activity [24].

- Incubation Conditions: Maintain physiological temperature (37°C), pH (6.5-7.4 in the small intestine), and use an oxygenated atmosphere [22].

- Detailed Protocol for Cell-Based Permeability Assays:

- Utilize Bio-relevant Media: For solubility and dissolution testing, use simulated biological fluids (e.g., Gamble's solution, artificial lysosomal fluid) that mimic the composition of the biological environment the compound will encounter [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing Permeability and Efflux in Caco-2 Cell Monolayers

This protocol is a standard for predicting intestinal absorption and identifying efflux transporter substrates [22].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Caco-2 cells | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that differentiates into enterocyte-like cells. |

| Transwell plates | Permeable supports for growing cell monolayers and separate donor/receiver compartments. |

| HBSS (Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution) | Transport buffer to maintain pH and osmotic balance. |

| Lucifer Yellow | Fluorescent paracellular marker to validate monolayer integrity. |

| Specific Transporter Inhibitors | e.g., P-gp inhibitor (Verapamil), to confirm transporter involvement. |

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Seeding: Seed Caco-2 cells at a high density on Transwell inserts. Allow 21-25 days for full differentiation and junction formation, monitoring TEER regularly.

- Experiment Pre-treatment: Before the assay, wash monolayers with transport buffer (e.g., HBSS). For inhibition studies, pre-incubate with the inhibitor for a set time.

- Bidirectional Transport Study:

- A-to-B (Apical to Basolateral): Add the test compound to the apical donor compartment and sample from the basolateral receiver compartment over time.

- B-to-A (Basolateral to Apical): Add the test compound to the basolateral donor compartment and sample from the apical receiver compartment.

- Sample Analysis: Use HPLC-MS/MS to quantify the compound concentration in all samples.

- Data Calculation:

- Calculate the Apparent Permeability (Papp) for both directions.

- Determine the Efflux Ratio: ER = Papp (B-A) / Papp (A-B). An ER > 2 suggests active efflux.

Protocol: Determining Fraction Unbound (fu) via Equilibrium Dialysis

This method determines the fraction of drug unbound to plasma proteins, which is critical for understanding active concentration [25].

Methodology:

- Setup: Use a dialysis device with two chambers separated by a semi-permeable membrane. Add drug-spiked plasma to one side (donor) and buffer to the other side (receiver).

- Incubation: Incubate the system at 37°C with gentle agitation until equilibrium is reached (typically 4-6 hours).

- Sampling and Analysis: Measure the total drug concentration in the plasma chamber and the unbound drug concentration in the buffer chamber.

- Calculation: Calculate the fraction unbound (fu) = Cbuffer / Cplasma.

Visualization of Key Pathways and Workflows

Oral Drug Absorption and First-Pass Effect

Mechanisms of Transport Across Biological Barriers

In Vitro Bioavailability Testing Workflow

Bioavailability—the proportion of a substance that enters circulation to exert biological effects—is a critical determinant in the safety assessment of chemicals and drugs. For researchers and scientists, understanding how regulatory frameworks address bioavailability is essential for designing compliant and ethical toxicity studies. This guide explores the specific requirements and emerging shifts under FIFRA (Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act), the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), and REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals). It provides actionable troubleshooting advice to navigate this complex regulatory landscape.

Bioavailability in Key Regulatory Frameworks

Different regulatory bodies approach bioavailability assessment with distinct requirements and emphases. The table below summarizes the core focus of each framework concerning bioavailability.

| Regulatory Framework | Region | Primary Focus for Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| FIFRA [28] [29] | United States | Assessing risks of pesticidal substances (e.g., in Plant-Incorporated Protectants) to human health and the environment; determining if substances are "plant regulators." |

| FDA [30] [31] | United States | Ensuring drug safety and efficacy, particularly through Bioavailability (BA) and Bioequivalence (BE) studies for new drugs and generics. |

| REACH [32] [33] | European Union | Evaluating the hazardous properties of chemical substances to manage risk; bioavailability informs the extent of exposure and required risk management measures. |

FIFRA: Regulating Pesticidal Substances

The EPA regulates pesticides under FIFRA, with a specific focus on biotechnology-derived products.

- Plant-Incorporated Protectants (PIPs): PIPs are pesticidal substances produced in living plants along with the genetic material necessary for their production [29]. When assessing the risks of PIPs, the EPA evaluates their potential to affect non-target organisms and their environmental fate [29].

- Enforcement and Clarity: The regulation of plant biostimulants under FIFRA can be complex. The EPA considers a product a pesticidal "plant regulator" if its claims suggest an intended physiological action (e.g., "root stimulator") [28]. The agency has issued significant penalties for the distribution of unregistered products with such claims [28]. Researchers should note that Congress is considering the Plant Biostimulant Act of 2025, which could amend FIFRA to exclude certain biostimulants from the definition of plant regulators [28].

FDA: Ensuring Drug Safety and Efficacy

The FDA mandates rigorous assessment of a drug's journey in the body.

- Data Integrity in Studies: For bioavailability and bioequivalence studies submitted in support of drug applications, the FDA provides guidance on achieving and maintaining data integrity for both clinical and bioanalytical portions [30]. This is critical for the reliability of study results.

- The Shift to New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): In a significant move, the FDA is phasing out animal testing requirements for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and other drugs, favoring more human-relevant NAMs [31]. This shift is driven by the low predictivity of animal models for human immune responses to mAbs, high costs, and ethical considerations [31]. The FDA encourages the use of Microphysiological Systems (MPS or organ-on-a-chip) and in silico models to generate data for regulatory submissions [31].

REACH: Managing Chemical Risks in the EU

REACH places the burden of proof for chemical safety on industry, where bioavailability plays a key role in exposure assessment.

- The Upcoming REACH Recast: Expected in late 2025, the REACH Recast will introduce major changes [32]. Key updates include:

- Time-bound registrations: Registrations may be valid for only 10 years, requiring renewal [32].

- Mandatory dossier updates: Companies must update dossiers when new hazard data emerges [32].

- Digital Product Passports (DPPs): Compliance data will need to be shared electronically through the supply chain [32].

- Generic Risk Approach (GRA): Restrictions may be fast-tracked for hazardous substances based on their intrinsic properties alone [32].

- Bioavailability in Site-Specific Risk Assessment: Understanding bioavailability is crucial for accurate risk assessment at contaminated sites. The EPA has developed methods, including in vivo mouse models and in vitro chemical extraction tests, to determine the bioavailability of metals like arsenic and lead in soil [33]. Using these site-specific bioavailability data can significantly alter cleanup strategies and reduce remediation costs [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

1. We are developing a plant biostimulant product. How can we determine if it is regulated as a pesticide under FIFRA?

- Answer: The primary factor is the claims you make about the product. If your product's labeling or marketing includes claims that it functions through physiological action to alter plant behavior (e.g., "stimulates root growth," "accelerates maturation"), the EPA will likely consider it a "plant regulator" and require FIFRA registration [28]. To avoid this, ensure claims are focused on improving soil nutrient conditions without implying a direct physiological effect on the plant [28].

- Troubleshooting: If you have already made pesticidal claims, you may need to recall marketing materials and revise your product's label. Consult EPA's 2020 "Draft Guidance for Plant Regulators and Claims" for the most current interpretation [28].

2. Our company needs to comply with the new REACH Recast. What are the most urgent steps we should take?

- Answer: You should act immediately on the following [32]:

- Conduct a REACH Readiness Audit: Review all your current substance registrations and identify any with data gaps.

- Engage Your Supply Chain: Proactively communicate with suppliers to gather full material disclosure (FMD) data, especially on Substances of Very High Concern (SVHCs).

- Plan for Dossier Updates: Establish a process to monitor new scientific data and promptly update your registration dossiers.

- Prepare for Digital Systems: Begin mapping the data required for the upcoming Digital Product Passports (DPPs).

3. The FDA is moving away from animal testing. What alternative methods are acceptable for preclinical bioavailability and toxicity testing?

- Answer: The FDA is endorsing a category of tools called New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) [31]. Acceptable methods include:

- Microphysiological Systems (MPS): Also known as organ-on-a-chip, these systems use human cells to create 3D, functioning models of human organs for high-fidelity toxicity and absorption testing [31].

- In silico Models: Computational models that can simulate and predict a drug's behavior in the body [31].

- Other In Vitro Models: This includes advanced cell cultures and organoids [34] [31].

- Troubleshooting: When submitting an Investigational New Drug (IND) application, you are encouraged to submit data from NAMs in parallel with traditional animal data. The FDA recognizes that no single NAM will be 100% accurate, so a combination of complementary approaches is often best [31].

4. We have inconsistent results in our oral drug bioavailability assays. What factors should we re-examine in our experimental design?

- Answer: Inconsistent oral bioavailability often stems from these common issues [34] [19]:

- Non-Biorelevant Dissolution Media: Using simple buffers instead of biorelevant media (e.g., FaSSGF/FeSSGF or FaSSIF/FeSSIF) that mimic the fed/fasted state and contain surfactants like bile salts [34].

- Ignoring First-Pass Metabolism: The drug may be extensively metabolized in the liver or gut wall before reaching systemic circulation. In vitro liver models (e.g., MPS) can help assess this [19] [31].

- Drug Physicochemical Properties: Factors like solubility, stability in different pH environments, and particle size can dramatically affect absorption [34] [19].

- Troubleshooting: Implement a transfer dissolution model that simulates the drug's movement from the stomach (acidic pH) to the intestines (neutral pH). This can help you observe and account for pH-dependent precipitation, a common cause of poor bioavailability [34].

Essential Experimental Protocols for Bioavailability Assessment

Protocol 1: Conducting a Bioavailability Study Using the Blood Concentration Method

This is the most common direct method for assessing systemic bioavailability [19].

Workflow Overview

Steps:

- Drug Administration: Administer the test formulation to subjects (human or animal) via the route being investigated (e.g., oral) [19].

- Blood Collection: Collect blood samples at predetermined time points post-administration (e.g., 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours). The interval and duration depend on the drug's known pharmacokinetics [19].

- Sample Processing: Centrifuge blood samples to separate plasma or serum from blood cells [19].

- Concentration Analysis: Use a sensitive and specific analytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS) to quantify the drug concentration in each plasma sample [19].

- Data Plotting: Plot the drug concentration in plasma against time to generate a concentration-time curve [19].

- Parameter Calculation: Calculate key pharmacokinetic parameters from the curve:

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): Represents the total exposure to the drug over time.

- C~max~ (Maximum Concentration): The peak concentration observed.

- T~max~ (Time to C~max~): The time taken to reach the peak concentration [19].

Troubleshooting Tip: If you encounter high variability between subjects, ensure the study population is well-defined and controlled for factors like diet, fasting state, and genetics. A larger sample size may also be needed [19].

Protocol 2: Using In Vitro MPS (Organ-on-a-Chip) for Toxicity Screening

This protocol leverages NAMs to assess organ-specific toxicity and metabolism, providing human-relevant data [31].

Workflow Overview

Steps:

- Model Selection and Culture: Select an MPS that models your target organ (e.g., liver, kidney, heart). Seed human primary or stem cell-derived cells into the microfluidic device and culture until they form a stable, functional micro-tissue [31].

- Dosing: Introduce the test compound into the MPS at clinically relevant concentrations. The microfluidic flow allows for repeated or continuous dosing, mimicking human exposure [31].

- Real-Time Monitoring: Continuously monitor the system for functional and viability endpoints. This can include:

- Biomarker Release: Measuring organ-specific biomarkers (e.g., albumin for liver, troponin for heart) in the effluent media.

- Metabolic Activity: Using assays like ATP content.

- Morphological Changes: Using microscopic imaging [31].

- Endpoint Analysis: At the end of the experiment, analyze the system for additional endpoints, such as metabolite formation (to assess bioactivation) and transcriptomic changes [31].

- Data Integration and IVIVE: Use the collected in vitro data to perform In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE), often with the aid of computational (in silico) models, to predict human physiological responses [31].

Troubleshooting Tip: If the MPS model shows poor functionality or rapid deterioration, verify the quality of the primary cells used and ensure the microfluidic system is properly maintaining physiological shear stress and nutrient/waste exchange [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

The following table lists essential materials used in bioavailability and toxicity studies, referencing the protocols above.

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Biorelevant Dissolution Media (FaSSGF, FeSSIF, etc.) [34] | Simulates the composition (pH, bile salts, lipids) of human gastric and intestinal fluids for more predictive in vitro dissolution testing. | Predicting the oral absorption of a poorly soluble drug under fasted vs. fed conditions [34]. |

| LC-MS/MS System [19] | (Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry) A highly sensitive and specific analytical instrument for quantifying low concentrations of drugs and metabolites in complex biological samples like plasma. | Measuring plasma concentration-time profiles for BA/BE studies [19]. |

| Microphysiological System (MPS) [31] | A microfluidic device that cultures living human cells in a 3D architecture to emulate the structure and function of human organs. Used for human-relevant toxicity and ADME screening. | Assessing liver toxicity or cardiotoxicity of a new drug candidate without animal testing [31]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line [34] | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that, when differentiated, exhibits properties of intestinal enterocytes. Used in in vitro models to predict drug permeability and absorption. | Screening the permeability of multiple lead compounds during early drug development [34]. |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes [31] | Primary human or animal liver cells, preserved for storage. Used in suspension or cultured formats to study hepatic metabolism and drug-drug interactions. | Evaluating the metabolic stability and metabolite profile of a new chemical entity [31]. |

| Bet-IN-12 | Bet-IN-12, MF:C30H32FN5O2, MW:516.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fteaa | FTEAA|MAO Inhibitor|For Research Use |

Measuring Bioavailability: From In Vivo Models to In Vitro and In Silico Approaches

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Earthworm Survival Assays: Low Dispersal or Activity Rates

Problem: Earthworms show low dispersal from assay tubes or low activity in soil quality tests, making it difficult to interpret results.

Solution: This problem often relates to suboptimal soil conditions or experimental setup. The table below outlines common issues and verified solutions based on established methodologies [35] [36].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Verified Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low dispersal in field assays | Poor soil quality (e.g., contamination, unfavorable pH) at the target site [36]. | Use a high-quality reference soil in the assay tubes. Correlate dispersal behavior with soil physicochemical properties like metal concentration, electrical conductivity, and pH [36]. |

| Uncertain earthworm activity in lab/field | Reliance on presence alone is unreliable; worms can be inactive for long periods [35]. | Implement a density-based separation method: Place earthworms in a 1.08 g cmâ»Â³ sucrose solution. Actively feeding (active) earthworms with soil-filled guts will sink; inactive ones with empty guts will float [35]. |

| Inconsistent activity measurements | Subjective visual assessment of estivation (dormancy) [35]. | Adopt the objective density-based method, which is highly correlated with visual estimation but is applicable to a wider range of species, including those that do not estivate [35]. |

Experimental Protocol: Earthworm Dispersal Assay for Soil Quality [36] This protocol provides a rapid, in-situ technique for assessing soil quality based on earthworm preference.

- Assay Setup: Insert multiple tubes containing a standardized, preferable reference soil into the soil at your target field sites.

- Introduction of Earthworms: Place individual earthworms into the center of each assay tube.

- Monitoring and Data Collection: After a set period (e.g., 24 hours), record the behavior of each earthworm. The endpoints are:

- Dispersed: The earthworm has moved from the tube into the surrounding target soil.

- Remained: The earthworm is still within the reference soil inside the tube.

- Avoided (Escaped): The earthworm has crawled up the tube to escape both soil options.

- Died: The earthworm has died.

- Interpretation: A high rate of dispersal into the surrounding soil indicates the target soil is of high quality and preferable to the earthworms.

Rodent Models: Low Bioavailability of Oral DHA Supplements

Problem: When administering Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) to rodent models for toxicity or efficacy studies, the plasma concentration and bioavailability of DHA are lower than expected.

Solution: Low bioavailability is often due to DHA's poor water solubility. The following solutions, proven in rodent studies, can enhance absorption [37] [38].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Verified Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low plasma DHA after oral gavage | Poor solubility and dispersion of standard DHA oil formulations [38]. | Co-administer DHA with a bioavailability enhancer. Alpha-tocopheryl phosphate mixture (TPM) has been shown to significantly increase DHA's ( C_{max} ) and AUC in a dose-dependent manner in rats [38]. |

| Variable DHA incorporation into target tissues (e.g., retina) | The chemical form (triglyceride vs. phospholipid) of the dietary omega-3 affects its distribution and incorporation [37]. | Select the chemical form based on the target tissue. For increased DHA and very long chain PUFA content in the retina, DHA-rich triglycerides and EPA-rich phospholipids were most effective in rat studies [37]. |

| Inconsistent tissue DHA levels | High dietary intake of linoleic acid (LA, n-6) can inversely compete with n-3 LC-PUFA incorporation, particularly in the retina [37]. | Control the dietary ratio of LA to ALA. Design experimental diets with a balanced ratio (e.g., between 4 and 5) to improve n-3 incorporation [37]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating DHA Bioavailability in Rodent Models [38] This protocol outlines a method to test the effectiveness of a bioavailability enhancer (TPM) on DHA absorption in rats.

- Formulation Preparation:

- Prepare control formulation: Mix DHA oil (e.g., Incromega DHA 500TG) with a vehicle like canola oil.

- Prepare experimental formulations: Dissolve TPM powder into canola oil with mixing and mild heat (40°C). Once cooled, mix with DHA oil to achieve the desired w/w ratios (e.g., 1:0.1 and 1:0.5 DHA-to-TPM).

- Animal Dosing:

- Use male Sprague-Dawley rats (200-300 g). House under standard conditions with free access to food and water.

- Randomize rats into treatment groups (e.g., n=10). Administer formulations via oral gavage. Doses should be calculated based on body weight (e.g., a low dose of 88.6 mg DHA/kg and a high dose of 265.7 mg DHA/kg).

- Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Collect blood plasma samples at multiple time points over 24 hours post-administration.

- Analyze DHA plasma concentration using appropriate analytical methods (e.g., gas chromatography).

- Data Analysis:

- Plot DHA plasma concentration over time.

- Calculate pharmacokinetic parameters: AUC (Area Under the Curve), which represents total exposure, and ( C_{max} ), the maximum concentration. Compare these parameters between control and TPM-formulated groups to assess bioavailability enhancement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Alpha-tocopheryl phosphate mixture (TPM) | A lipidic excipient that forms vesicles to encapsulate and solubilize poorly water-soluble nutrients like DHA, significantly improving their oral bioavailability in rodent models [38]. |

| Sucrose Solution (1.08 g cmâ»Â³) | Used for density-based separation of active and inactive earthworms. Active earthworms with soil-filled guts have a higher density and sink in this solution [35]. |

| Incromega DHA 500TG | A commercially available triglyceride-form of omega-3 oil, predominantly containing DHA, used as a standard for dosing in rodent bioavailability studies [38]. |

| Allolobophora chlorotica, Aporrectodea caliginosa | Species of endogeic earthworms (soil-feeding) commonly used in soil quality and toxicity testing assays [35]. |

| Sprague-Dawley Rats | An outbred strain of albino rat, frequently used as the rodent model in preclinical toxicology and pharmacokinetic studies, including DHA bioavailability research [38]. |

| Krill Oil | A natural source of omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) where they are present primarily in the phospholipid form, used in studies comparing the bioavailability of different chemical forms [37]. |

| rel-Biperiden-d5 | rel-Biperiden-d5, MF:C21H29NO, MW:316.5 g/mol |

| Trk-IN-16 | Trk-IN-16, MF:C19H20FN5O, MW:353.4 g/mol |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Earthworm Activity and Soil Quality Assessment

Enhancing DHA Bioavailability in Rodents

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Bioaccessibility Extraction Methods

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Underestimated bioaccessibility | Insufficient sink capacity in extraction medium [39] | Implement infinite sink conditions (e.g., MEBE, Tenax, sorptive sinks); maximize acceptor-to-sample capacity ratio [39] [40]. |

| Low method reproducibility | Non-standardized assay techniques and methodology [41] | Adhere to validated protocols (e.g., UBM, SBRC); ensure within-lab repeatability (<10% RSD) and between-lab reproducibility (<20% RSD) [41]. |

| Poor correlation with in vivo bioavailability | Weak in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) [41] | Validate method against established animal models; target a linear correlation coefficient (r) > 0.8 [41]. |

| Slow desorption kinetics | Strong sorption to soil organic matter or black carbon; aging effects [39] [40] | Use a depletion-based method (e.g., sequential Tenax extraction) to measure the rapidly desorbing fraction (Frapid) [40] [42]. |

| Difficulty in analyte separation | Incomplete separation of extraction beads (e.g., Tenax) from soil matrix [39] | Use a physical membrane (e.g., LDPE in MEBE) to separate the desorption medium from the acceptor phase [39]. |

| Low analyte recovery from sink | High retention in sorptive polymers (e.g., PDMS-activated carbon) [39] | Select a sink that allows for easy back-extraction (e.g., silicone rods) or provides a directly analyzable extract (e.g., ethanol in MEBE) [39] [40]. |

Method Selection Guide

Table 2: Comparison of Key Chemical Extraction Methods for Bioaccessibility

| Method | Target Contaminants | Measured Fraction | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Enhanced Bioaccessibility Extraction (MEBE) [39] | HOCs (e.g., PAHs) | Bioaccessible | Independently controls desorption conditions and sink capacity; produces HPLC-ready extracts [39]. | Method is relatively new; requires specific equipment (LDPE membranes) [39]. |

| Tenax Extraction [40] [42] | HOCs | Rapidly Desorbing Fraction (Frapid) or 6-hour fraction (F6h) | Understands desorption kinetics; cost-effective as Tenax is reusable [40] [42]. | Time-consuming and laborious (sequential); difficult bead separation from soil [39] [40]. |

| HPCD Extraction [43] | HOCs (e.g., PAHs) | Labile/Desorbable Fraction | Rapid, easy operation; correlates well with microbial degradation [43]. | Species-dependent performance; limited extraction capacity [40]. |

| Diffusive Gradients in Thin-films (DGT) [44] [45] | Metal(loid)s (e.g., Cd, As, Pb) | Labile/Bioavailable Concentration | In-situ measurement; reflects dynamic resupply from soil solid phase; correlates well with plant uptake [44] [45]. | Not suitable for hydrophobic organic contaminants [44]. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) [40] [42] | HOCs | Freely Dissolved Concentration (Cfree)/Chemical Activity | In-situ application; can be deployed in various media; no solvent required [40] [42]. | Longer equilibration times for some compounds; low fiber capacity [42]. |

| Unified BARGE Method (UBM) [41] | Metal(loid)s | Bioaccessible (Gastrointestinal) | Physiologically-based; standardized for human health risk assessment [41]. | Complex protocol with multiple phases; specific to ingestion exposure pathway [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between bioaccessibility and bioavailability?

A1: Bioaccessibility refers to the fraction of a contaminant that is released from its matrix (e.g., soil, food) into digestive or environmental fluids and is therefore available for absorption [46] [47]. It represents the maximum potentially available pool. Bioavailability, specifically absolute bioavailability (ABA), is the fraction of the ingested contaminant that crosses the gastrointestinal barrier, enters systemic circulation, and is available for distribution to tissues [41]. In vitro bioaccessibility (IVBA) assays are often used as a surrogate to estimate the more complex and costly in vivo bioavailability [41].

Q2: When should I use a method that measures the rapidly desorbing fraction (like Tenax) versus one that measures freely dissolved concentration (like SPME)?

A2: The choice depends on the process you wish to predict.

- Use Tenax extraction (measuring bioaccessibility) for processes like biodegradation or when bioaccumulation is influenced by the ingestion of soil particles, as these are governed by the mass of contaminant that can be mobilized within a relevant time frame [40] [42].

- Use SPME (measuring freely dissolved concentration, Cfree, related to chemical activity) for predicting baseline toxicity or the passive diffusive uptake of contaminants by organisms like aquatic invertebrates, as these are driven by chemical activity gradients [40] [42]. Both methods have been successfully correlated to bioaccumulation in various scenarios.

Q3: My research involves metals in soils. Which method is most reliable for predicting plant uptake?

A3: Recent studies indicate that the Diffusive Gradients in Thin-films (DGT) technique often shows a superior correlation with plant uptake of metals like Cd compared to traditional chemical extraction methods (e.g., CaClâ‚‚, DTPA, HAc) [44] [45]. This is because DGT mimics the dynamic root uptake by creating a sink for metal ions, considering both the soil solution concentration and the resupply from the solid phase [45]. For direct human health risk assessment via ingestion, physiologically-based extraction methods like the Unified BARGE Method (UBM) are more appropriate [41].

Q4: How can I validate that my in vitro bioaccessibility results are meaningful for in vivo scenarios?

A4: Validation involves establishing a strong correlation between your in vitro measurements and results from in vivo bioavailability studies. According to expert recommendations, a robust model should demonstrate [41]:

- A linear relationship with a correlation coefficient (r) > 0.8.

- A slope of the regression line between 0.8 and 1.2.

- Acceptable precision, with within-lab repeatability of < 10% relative standard deviation (RSD) and between-lab reproducibility of < 20% RSD.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Bioaccessibility assays

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Hydropropyl-β-Cyclodextrin (HPCD) | Acts as a mild solubilizing agent that can form inclusion complexes with HOCs, mimicking desorption into aqueous phases [39] [43]. | HPCD shake extraction to predict the microbial bioaccessibility of PAHs in soil [43]. |

| Tenax Beads | A porous polymer used as a sorptive sink to continuously remove HOCs desorbed from soil, allowing measurement of the rapidly desorbing fraction [40]. | Sequential or single-point (e.g., 6-hour) Tenax extraction to estimate the bioaccessible fraction of PCBs in sediments [40] [42]. |

| Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) Membrane | A semipermeable membrane that physically separates a mild aqueous desorption medium from an organic acceptor solvent, creating a defined and infinite sink [39]. | Used in the MEBE setup to extract PAHs from soil with independent control over desorption conditions and sink capacity [39]. |

| SPME Fibers | Coated fibers that absorb HOCs until equilibrium is reached with the freely dissolved concentration (Cfree) in the sample, used to measure chemical activity [40] [42]. | Deploying PDMS-coated fibers in water or sediment suspensions to predict the bioavailability of pesticides to benthic organisms [42]. |

| Polyoxymethylene (POM) Sampler | A passive equilibrium sampler used to measure the freely dissolved concentration (Cfree) of HOCs in sediment or soil [40]. | Determining Cfree of PAHs in sediment porewater for use in equilibrium partitioning models [40]. |

| Enzymes & Bile Salts | Key components of physiologically-based extraction tests that simulate the solubilizing and digestive conditions of the human gastrointestinal tract [41]. | Incorporated into the Unified BARGE Method (UBM) to assess the human bioaccessibility of arsenic in contaminated soils [41]. |

| Egfr-IN-69 | Egfr-IN-69, MF:C31H37Cl2N7O3S, MW:658.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Akr1C3-IN-6 | Akr1C3-IN-6|Potent AKR1C3 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Akr1C3-IN-6 is a potent and selective AKR1C3 inhibitor for cancer research. It targets castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) mechanisms. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Conceptual Framework and Experimental Workflows

Conceptual Framework for Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility

The following diagram illustrates the key concepts and their relationships in assessing contaminant fate and effects.

Generalized Workflow for a Bioaccessibility Experiment

This workflow outlines the common steps for conducting and validating a bioaccessibility study, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core practical difference between linear and log-linear trapezoidal methods for calculating AUC?

The choice primarily affects accuracy in different phases of drug disposition. The linear trapezoidal method uses linear interpolation between all concentration-time points and is simple to implement but can overestimate AUC during the elimination phase because it does not account for the exponential (first-order) nature of drug elimination. In contrast, the logarithmic trapezoidal method uses logarithmic interpolation and is more accurate for decreasing concentrations. For the most accurate overall result, a hybrid approach is recommended: use the linear method for rising concentrations (absorption phase) and the logarithmic method for declining concentrations (elimination phase). This hybrid is often called "Linear-Up Log-Down." The impact of the method is more pronounced with widely spaced time points [48].

Q2: My PK model fails to converge. Could poor initial parameter estimates be the problem?

Yes, this is a common issue. Nonlinear mixed-effects models, which are central to population PK (PopPK) analysis, rely on adequate initial parameter estimates for efficient optimization. Poor initial estimates can lead to failed convergence or incorrect final parameter estimates. This is especially problematic with sparse data, where traditional methods like non-compartmental analysis (NCA) struggle. Automated pipelines that use data-driven methods (e.g., adaptive single-point methods, graphic methods, and parameter sweeping) are now being developed to generate robust initial estimates for parameters like clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (Vd), thereby improving model convergence and reliability [49].

Q3: When is a suprabioavailable product a regulatory concern, and what are the next steps?

A suprabioavailable product displays an appreciably larger extent of absorption than the approved reference product. This is a regulatory concern because it could lead to higher systemic exposure and potential toxicity if patients are switched to the new product without dose adjustment. If suprabioavailability is found, the developer should consider formulating a lower dosage strength. A comparative bioavailability study comparing the reformulated product with the reference product must then be submitted. If a lower strength is not developed, the dosage recommendations for the suprabioavailable product must be directly supported by clinical safety and efficacy studies [50].

Q4: What is the role of Incurred Sample Reanalysis (ISR) in a bioanalytical study?

ISR is a regulatory requirement (e.g., in the EMA Guideline on Bioanalytical Method Validation) to confirm the reliability and reproducibility of the analytical method used to generate PK data. It involves reanalyzing a portion of study samples in a separate analytical run to verify that the original concentration data are valid. ISR helps identify issues not always caught during method validation, such as metabolite back-conversion, sample matrix effects, or analyte instability. A lack of ISR data requires a strong scientific justification, especially for pivotal studies like bioequivalence trials, as it calls into question the validity of the entire dataset [50].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Model Convergence Failures in PopPK Analysis

Failed model convergence often stems from inadequate initial parameter estimates. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and resolve this issue.

Table: Strategies for Generating Initial Parameter Estimates

| Scenario | Problem | Recommended Method | Key Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Rich | NCA may be reliable, but model initial estimates are needed. | Naïve Pooled NCA, Graphic Methods [49] | Pool all individual data or use plots to estimate primary parameters. |

| Sparse Data | NCA is unreliable or impossible; no robust starting points. | Adaptive Single-Point Method, Parameter Sweeping [49] | Use population-level summarization or test a range of values via simulation. |

| Complex Models | Multi-compartment models or nonlinear elimination. | Parameter Sweeping [49] | Simulate concentrations for candidate parameter values and select the best fit. |

Protocol: Parameter Sweeping for Complex Models [49]

- Define the Range: Establish a biologically plausible range for each parameter that lacks an initial estimate (e.g., absorption rate constant

Ka). - Generate Candidates: Create a set of candidate parameter values, often by sampling across the defined range.