Bioavailability and Environmental Fate of Contaminants: Mechanisms, Modeling, and Implications for Risk Assessment

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the processes governing the environmental fate and bioavailability of contaminants, with a specific focus on implications for pharmaceutical research and development.

Bioavailability and Environmental Fate of Contaminants: Mechanisms, Modeling, and Implications for Risk Assessment

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the processes governing the environmental fate and bioavailability of contaminants, with a specific focus on implications for pharmaceutical research and development. It explores the fundamental physical, chemical, and biological interactions that determine contaminant exposure, reviews advanced modeling and detection methodologies for predicting bioavailability, and addresses key challenges in incorporating these concepts into accurate risk assessment frameworks. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes recent scientific advances to bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and practical application in environmental and health risk management.

Understanding Bioavailability: Defining the Processes that Govern Contaminant Exposure

What is Bioavailability? Clarifying Definitions and Conceptual Frameworks

Bioavailability is a foundational concept critical to accurately assessing the risk and impact of chemicals, as the total concentration alone is a poor indicator of the fraction that is actually absorbed by an organism and can elicit a biological response [1]. In essence, it describes the extent to which a substance is taken up and becomes available at the site of physiological activity within a living organism [2]. First introduced as a concept in 1975, the principle of bioavailability now applies to various environments, including water, soil, sediment, and air [1].

The significance of bioavailability is clearest in a comparative context. For a long time, soil quality standards and risk assessment procedures in most countries were based on the total amount of pollutants. However, the actual risk and impact of pollutants may be equal to or lower than this total amount, as not all pollutants can be absorbed during biological processes [1]. The extent of bioavailability has profound implications, influencing everything from the efficacy and dosing of pharmaceutical drugs to the ecological risk assessment and remediation strategies for contaminated land [3] [1].

Discipline-Specific Definitions and Frameworks

The term "bioavailability" lacks a single, universal definition and is often interpreted through a discipline-specific lens, leading to a variety of nuanced meanings [2]. The core discrepancy lies in whether bioavailability is viewed as a static quantity (the fraction available for absorption) or a dynamic process (the rate of absorption).

Pharmacology and Toxicology

In pharmacology, bioavailability is a subcategory of absorption and is defined as the fraction (%) of an administered drug that reaches the systemic circulation in an unchanged form [3] [4]. This definition provides a quantitative framework:

- Absolute Bioavailability (

F): This compares the bioavailability of a drug after non-intravenous administration (e.g., oral, dermal) to its bioavailability after intravenous (IV) administration, which is, by definition, 100% [3] [5] [4]. It is calculated by correcting the ratio of the Areas Under the plasma drug concentration-time Curves (AUC) for the difference in administered dose [3]. - Relative Bioavailability: This measures the bioavailability of a specific formulation of a drug compared to another formulation, usually an established standard [3]. This is a key measure for assessing bioequivalence between two drug products, such as a brand-name drug and its generic version [3].

Toxicologists often extend this definition to encompass the fraction of a chemical that is accessible for absorption and can reach the site of toxicological action [2].

Nutritional Science

For dietary supplements, herbs, and nutrients, bioavailability generally designates simply the quantity or fraction of the ingested dose that is absorbed [3]. A key difference from pharmacology is the lack of well-defined standards, as the utilization and absorption of a nutrient are heavily influenced by the nutritional status and physiological state of the subject, leading to even greater inter-individual variation [3].

Environmental Science

In environmental science, the concept is applied to contaminants in soils and sediments. Here, bioavailability is the measure by which various substances in the environment may enter into living organisms [3]. It is a crucial, often limiting, factor in crop production and in the removal of toxic substances from the food chain [3]. To clarify the ongoing discussion, the related concept of bioaccessibility is often used to describe the fraction of a contaminant that is desorbable and potentially available for absorption, whereas bioavailability refers to the fraction that actually crosses an organism's cellular membrane [6] [1].

Table 1: Definitions of Bioavailability Across Disciplines

| Discipline | Primary Definition | Key Focus | Common Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacology | Fraction of an administered dose that reaches the systemic circulation unchanged [3] [4]. | Drug efficacy and safety, dosing. | Absolute Bioavailability (F), Relative Bioavailability, AUC [3]. |

| Toxicology | Fraction of a chemical that is absorbed and can reach a target site to cause an adverse effect [2]. | Chemical risk assessment. | Bioavailability factor (BF), internal dose. |

| Nutritional Science | Quantity or fraction of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed [3]. | Nutritional status and physiological utilization. | Absorption fraction, AUC. |

| Environmental Science | Measure by which substances in the environment enter living organisms [3]; Measure of the potential for a chemical to enter an ecological or human receptor [2]. | Ecological risk assessment, remediation. | Bioaccessible fraction, freely dissolved concentration (C~free~), Biota-Sediment Accumulation Factor (BSAF). |

Given the diversity of definitions, the National Research Council (NRC) proposed a shift in focus from a single definition to the concept of "bioavailability processes" for contaminants in soils and sediments. These are defined as "the individual physical, chemical, and biological interactions that determine the exposure of plants and animals to chemicals associated with soils and sediments" [2]. This framework aims to make the incorporation of bioavailability into risk assessments more transparent and defensible.

Key Parameters and the Conceptual Framework

The environmental bioavailability of contaminants is primarily understood through two key parameters, which represent different endpoints in the exposure pathway [6].

Bioaccessibility and the Rapid Desorption Fraction

Bioaccessibility refers to the fraction of a contaminant that is weakly or reversibly sorbed to the solid matrix and can therefore undergo rapid desorption into the aqueous phase [6]. This fraction represents the pool of contaminant that is accessible to an organism over a relevant time scale. For example, as an organism moves through or ingests soil, or as bacteria attempt to degrade a contaminant, the chemical must first enter the water phase. The desorbable, or bioaccessible, fraction replenishes the freely dissolved chemical as it is removed by these processes [6]. This parameter is operationally defined, meaning its measured value depends heavily on the specific extraction method used (e.g., solvent, time, temperature) [6].

Chemical Activity and the Equilibrium Partitioning Theory

Chemical activity describes the potential of a contaminant to undergo spontaneous physicochemical processes like diffusion and partitioning [6]. At equilibrium, the chemical activity is equal in all phases (e.g., soil organic matter, pore water, biota). For hydrophobic organic contaminants (HOCs) at environmentally relevant levels, chemical activity is represented by the freely dissolved concentration (C~free~) in the pore water [6]. The Equilibrium Partitioning (EqP) theory uses this principle to predict bioavailability, stating that at equilibrium, the concentration in one compartment (e.g., biota) is proportional to C~free~ in another (e.g., water) via a partition coefficient [6]. Unlike bioaccessibility, C~free~ should be a singular value for a given sample and is typically measured using equilibrium passive samplers [6].

Table 2: Key Parameters in Environmental Bioavailability

| Parameter | Definition | Environmental Relevance | Common Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioaccessibility | The contaminant fraction that is desorbable and potentially available for absorption [6] [1]. | Predicts bioavailability for processes like biodegradation and ingestion by invertebrates [6]. | Mild solvent extraction, hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPCD) extraction, Tenax desorption [6]. |

| Chemical Activity / C~free~ | The freely dissolved concentration, representing the contaminant's potential for spontaneous partitioning [6]. | Predicts baseline toxicity, bioaccumulation in passive diffusers, and acute aquatic toxicity [6]. | Equilibrium passive samplers (e.g., SPME, POM, PEDs) [6]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the total contaminant in the environment and its eventual biological impact, highlighting the key concepts of bioaccessibility and bioavailability.

Methodologies for Assessing Bioavailability

A wide array of methods has been developed to measure bioavailability and its related parameters. These techniques can be broadly categorized into chemical methods that simulate biological uptake and biological assays that measure it directly.

Chemical Assessment Methods

Chemical methods are designed to be rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible tools for predicting bioavailability. They primarily target either the bioaccessible fraction or the chemical activity (C~free~) [6].

Partial Extraction Techniques (Measuring Bioaccessibility): These methods use a mild extractant to remove the rapidly desorbing contaminant fraction.

- Mild Solvent Extraction: Uses a mild organic solvent to partially extract HOCs from the soil. The result is highly dependent on the solvent and soil type [6].

- HPCD Extraction: Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin acts as a contaminant sink, mimicking bacterial membranes. It is a fast and easy operation but has limited extraction capacity [6].

- Tenax Extraction: Uses Tenax resin as a continuous sink to trap desorbed contaminants. It can be a time-consuming sequential extraction to understand desorption kinetics or a simplified single 6-hour extraction [6].

Equilibrium Sampling Techniques (Measuring C~free~): These methods use a passive sampler that equilibrates with the soil or sediment pore water.

- Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME): A polymer-coated fiber is exposed to the sample. The amount of contaminant absorbed on the fiber at equilibrium is directly related to C~free~ [6].

- Polyoxymethylene (POM) and Polyethylene Devices (PED): Thin sheets of polymer are incubated with the sample until equilibrium is reached, after which the contaminant concentration in the polymer is used to calculate C~free~ [6].

Biological and In Vivo Assessment

Biological methods provide a direct measure of bioavailability by using living organisms as the assessment tool.

- In Vivo Animal Studies: For human health risk assessment, these studies determine the absolute oral bioavailability of a contaminant by comparing the internal dose following ingestion of contaminated soil to the internal dose following intravenous administration of the pure contaminant [2].

- Bioaccumulation Studies with Invertebrates: Organisms such as earthworms or aquatic oligochaetes are exposed to contaminated soil or sediment. The concentration of the contaminant accumulated in their tissues after a defined period serves as a direct measure of its bioavailability [6].

- Biodegradation Studies: The extent and rate of microbial degradation of a contaminant in a natural sample can be used as an indicator of its bioavailability to the degrading microbial community [6].

The following workflow diagram outlines the general experimental protocol for assessing bioavailability using a passive sampling approach, a common method for determining C~free~.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The experimental assessment of bioavailability relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and tools used across different methodological approaches.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioavailability Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Primary Application Area |

|---|---|---|

| Tenax TA | A polymeric resin that acts as an infinite sink to trap hydrophobic organic contaminants desorbed from soil/sediment, allowing measurement of the rapidly desorbing fraction [6]. | Bioaccessibility Measurement |

| Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin (HPCD) | A non-toxic, ring-shaped sugar molecule that forms inclusion complexes with HOCs, mimicking uptake by bacterial cell membranes and estimating the bioaccessible fraction [6]. | Bioaccessibility Measurement |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Polymer-coated fibers (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane) that absorb contaminants from pore water until equilibrium is reached, used to measure the freely dissolved concentration (C~free~) [6]. | Chemical Activity (C~free~) Measurement |

| Polyoxymethylene (POM) Samplers | Thin sheets of a dense polymer that serve as an equilibrium passive sampler for measuring C~free~ of HOCs in sediments and soils [6]. | Chemical Activity (C~free~) Measurement |

| Simulated Biological Fluids | Chemically defined solutions that mimic the gastric or intestinal environment (e.g., pH, enzymes) to estimate the human bioaccessible fraction of contaminants via ingestion [2]. | In Vitro Bioaccessibility (Human Health) |

| 0.1 mol/L CaClâ‚‚ Solution | A mild neutral salt solution used as an extractant to estimate the "exchangeable" or potentially plant-available fraction of heavy metals in soils [1]. | Phytotoxicity & Plant Uptake |

| Octamethyl-1,7-tetrasiloxanediol | Octamethyl-1,7-tetrasiloxanediol, CAS:3081-07-0, MF:C8H26O5Si4, MW:314.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Porritoxin | Porritoxin|CAS 143114-82-3|Research Grade | Porritoxin is a phytotoxin with anti-tumor-promoting research applications. This product is for research use only and not for human consumption. |

Regulatory Application and Future Directions

The understanding of bioavailability is increasingly being translated from a scientific concept into a practical tool for environmental regulation and risk assessment.

Many policymakers and regulators are now accepting that bioavailability should form a fundamental basis for risk assessment and for formulating soil remediation values and reference values [1]. For instance:

- United States: The US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has incorporated bioavailability into its water quality benchmarks for metals like copper through the use of the Biotic Ligand Model (BLM) [1].

- Europe: Germany and Switzerland use leaching tests (e.g., with 0.1 mol/L NaNO₃) to determine guide and trigger values for heavy metals in soil, integrating mobility and bioavailability into their standards [1].

- China: The Fujian Province local standard is a pioneering example of using effective concentrations of heavy metals extracted with 0.1 mol/L CaClâ‚‚ or DTPA as a classification standard for agricultural soil pollution [1].

Future directions in bioavailability research focus on standardizing measurement protocols, better integrating multi-disciplinary techniques, and developing more sophisticated in silico and modeling approaches. Computational models, such as physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models and tools like GastroPlus and SimCyp, are gaining traction for predicting absorption and bioavailability, thereby accelerating drug development and environmental risk assessment [7] [8]. The ongoing challenge and focus of research is to establish highly correlated, standardized methods for evaluating bioavailability that are universally accepted and can be reliably used to inform remediation strategies and protect human and ecosystem health [1].

For over three decades, assessing and remediating soils and sediments contaminated by industrial chemicals has been a national priority, with a central focus on the risks these contaminants pose to humans and ecological receptors [2]. Evaluation of exposure is a key component of chemical risk assessment, and understanding the factors that influence exposure enables decision-makers to develop solutions for environmental contamination [2]. The bioavailability of contaminants—the percentage of total contaminant levels to which organisms are actually exposed—has significant implications for the cleanup of contaminated media [2]. National attention on bioavailability stems from a growing recognition that soils and sediments bind chemicals to varying degrees, thereby altering their availability to other environmental media and to living organisms [2].

The physiological characteristics or "niche" of plant and animal species significantly influence chemical exposure, such that the same contaminated material may present vastly different exposure profiles across species [2]. This altered availability has been described using various terms including partitioning, reduced desorption rates, sequestration, and limited absorption through biological membranes [2]. In this review, we adopt the term "bioavailability processes," defined as the individual physical, chemical, and biological interactions that determine the exposure of plants and animals to chemicals associated with soils and sediments [2]. This process-based approach provides a more transparent framework for identifying relevant mechanisms, gaining mechanistic understanding, and evaluating tools for assessing bioavailability in environmental risk assessment.

Defining Bioavailability: Concepts and Terminology

Bioavailability has been defined in various discipline-specific ways, creating potential confusion in interdisciplinary research and regulation. As shown in Table 1, definitions range from environmental science perspectives focusing on accessibility for assimilation and potential toxicity, to pharmacological definitions emphasizing absorption into systemic circulation [2].

Table 1: Key Definitions of Bioavailability and Related Terms

| Term | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Bioavailability (Environmental) | "The extent to which a substance can be absorbed by a living organism and can cause an adverse physiological or toxicological response." | Battelle and Exponent, 2000 [2] |

| Bioavailability (Toxicological) | "The fraction of an administered dose that reaches the central (blood) compartment." | NEPI, 2000a [2] |

| Absolute Bioavailability | "The fraction or percentage of an external dose which reaches the systemic circulation." | Hrudy et al., 1996 [2] |

| Relative Bioavailability | "Refers to comparative bioavailabilities of different forms of a chemical or for different exposure media containing the chemical." | Ruby et al., 1999 [2] |

| Bioavailability Processes | "The individual physical, chemical, and biological interactions that determine the exposure of plants and animals to chemicals associated with soils and sediments." | National Research Council, 2003 [2] |

In pharmacological contexts, absolute bioavailability (F) represents the fraction of an administered dose that reaches systemic circulation, with intravenous administration providing 100% bioavailability by definition [5]. Relative bioavailability compares absorption between different forms of a chemical or different exposure media, often expressed as a relative absorption factor [2]. It is crucial to distinguish between absorption (the passage of a drug through intestinal tissue into the portal vein) and oral bioavailability, which requires the compound to survive gastrointestinal absorption and metabolism, blood metabolism, and hepatic clearance [5].

Physical and Chemical Processes Governing Bioavailability

Phase Distribution and Partitioning

The distribution of hydrophobic chemicals between aqueous, solid, and dissolved organic phases fundamentally controls their biological availability in aquatic environments [9]. The truly dissolved aqueous fraction represents the directly bioavailable form of xenobiotic chemicals, with phase distribution behavior predictable using physicochemical properties [9]. These distributions are influenced by:

- Sediment-water exchange processes that regulate contaminant mobility across this critical interface [10] [11]

- Interactions with particulate and dissolved organic matter that sequester hydrophobic organic compounds [10]

- Photochemical processes that can alter chemical structure and availability through light-mediated reactions [10] [11]

- Redox potential and pH fluctuations in dynamic sediment-water environments that modify metal mobility and organic compound availability [10]

Molecular Interactions and Binding

Physicochemical factors including water hardness, pH, and temperature significantly influence toxicity in freshwater systems by modifying chemical speciation and organismal susceptibility [10]. For metals, ligands in aquatic environments play crucial roles in determining metal bioavailability through complex formation [10]. The binding of hydrophobic organic contaminants to dissolved organic macromolecules, such as humic acid, can reduce uptake by biological membranes, as demonstrated for contaminants like benzo[a]pyrene and tetrachlorobiphenyl passing through fish gills [9].

Table 2: Key Physicochemical Factors Affecting Contaminant Bioavailability

| Factor | Effect on Bioavailability | Representative Contaminants Affected |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Alters chemical speciation, particularly for metals; affects membrane permeability | Metals, ionizable organic compounds |

| Redox Potential | Influences metal valence state and mobility; affects degradation of organic contaminants | Metals, PAHs, chlorinated compounds |

| Dissolved Organic Carbon | Binds hydrophobic compounds, reducing freely dissolved concentration | PAHs, PCBs, dioxins |

| Water Hardness | Competes with metals for binding sites; affects organism susceptibility | Metals (Cd, Cu, Zn) |

| Temperature | Affects metabolic rates, chemical degradation, and partitioning | Nearly all contaminants |

Biological Processes in Bioavailability

Membrane Transport and Physiological Uptake

For aquatic organisms, chemical uptake occurs primarily through the gills, where rate-limiting barriers control xenobiotic transfer from water to the organism [9]. The gill epithelium represents the initial biological interface for waterborne contaminants, with uptake potentially controlled by transfer to storage tissues via blood flow to adipose tissue [9]. For hydrophobic organic contaminants, research has demonstrated that dissolved organic macromolecules can reduce uptake by the gills of rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri), highlighting the interplay between chemical binding and biological uptake [9].

Kinetic Limitations and Physiological Regulation

Toxicokinetic modeling approaches have been developed to investigate the toxicity of mixtures of organic chemicals, using one-compartment, first-order-kinetics models to predict time courses of toxicant action [9]. Organisms possess physiological and biochemical mechanisms that regulate the accumulation and toxicity of environmental chemicals, including biotransformation enzymes, membrane transporters, and storage mechanisms [10]. Understanding the choreography of contaminant kinetics—quantifying the uptake of chemicals by organisms—requires approaches that account for both environmental availability and biological processing [10].

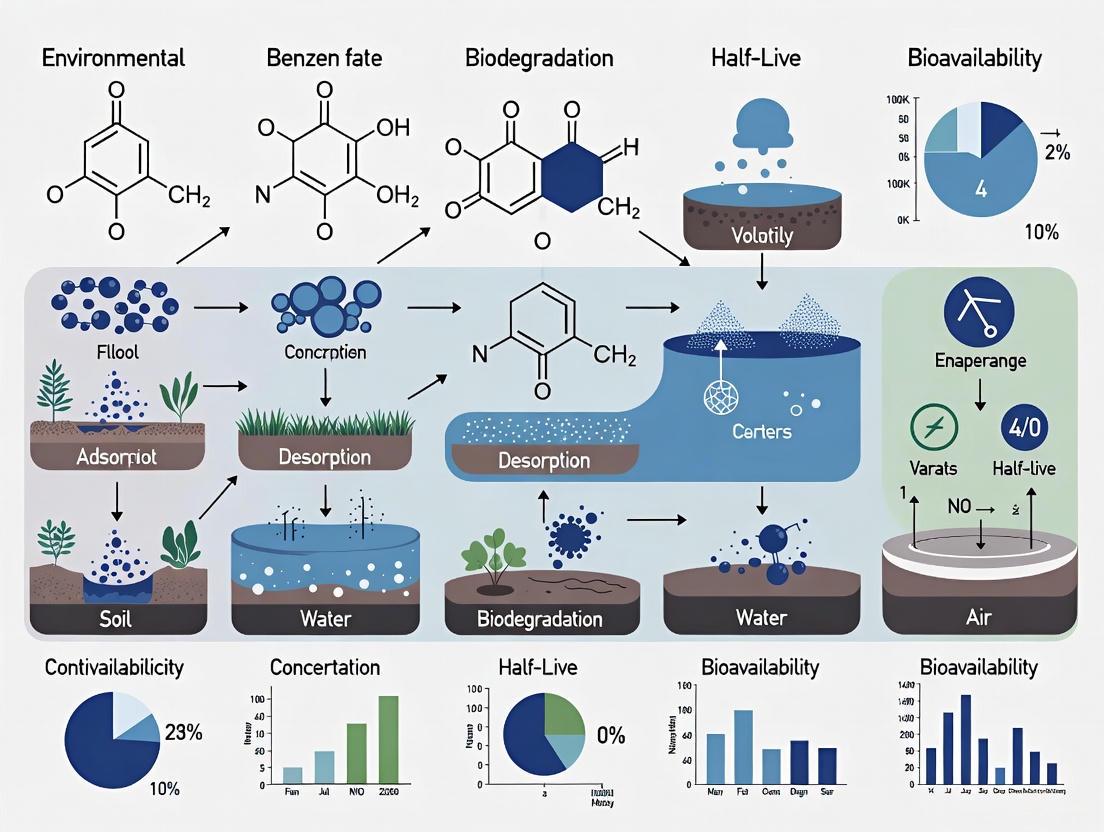

The following diagram illustrates the key physical, chemical, and biological processes that collectively determine contaminant bioavailability in environmental systems:

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Bioavailability Assessment Protocols

Bioavailability studies follow structured protocols with key components including study objectives, experimental design, subject selection, and statistical analysis [12]. Experimental designs for bioavailability assessment include:

- Parallel study designs where different groups receive different formulations, though this approach is subject to inter-subject variations [12]

- Crossover designs including Latin square and balanced incomplete block designs that minimize inter-subject variation by having subjects serve as their own controls [12]

- Washout periods between study periods to eliminate carryover effects, though extended washout periods can increase subject dropout rates [12]

For environmental assessments, bioavailability measurements can utilize plasma level-time studies, urinary excretion methods, acute pharmacological responses, or therapeutic responses [12]. Key parameters assessed include AUC (area under the concentration-time curve), Cmax (maximum concentration), Tmax (time to reach maximum concentration), and elimination half-life (T½) [12].

Bioequivalence Testing Frameworks

In regulatory contexts for human pharmaceuticals, bioequivalence summary tables provide standardized formats for data representation consistent with FDA recommendations [13]. These tables, required for Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs), include sixteen key tables covering submission summaries, bioavailability studies, statistical analyses, bioanalytical method validation, and in vitro dissolution studies [13]. The Division of Bioequivalence (DBE) within the Office of Generic Drugs reviews these studies to determine therapeutic equivalence based on pharmaceutical equivalence and established bioequivalence [13].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Bioavailability Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Sediments | Standardized matrix for controlling organic matter and particle size effects on contaminant partitioning | Sediment toxicity testing [9] |

| Passive Sampling Devices | Measure freely dissolved contaminant fraction; predict bioavailable concentration | Field and laboratory studies [5] |

| Chemical Extractants | Simulate gastrointestinal fluids or environmental release; estimate bioaccessibility | In vitro bioavailability assays [5] |

| Dissolved Organic Matter | Study complexation effects on contaminant mobility and uptake | Aquatic toxicology [9] |

| Defined Media | Control physicochemical parameters (pH, hardness, ionic composition) | Laboratory exposure studies [10] |

| Radiolabeled Compounds | Track contaminant fate, metabolism, and distribution in biological systems | Toxicokinetic studies [9] |

| Biomimetic Membranes | Assess passive diffusion and membrane permeability | In vitro absorption studies [5] |

| Teniloxazine | Teniloxazine, CAS:62473-79-4, MF:C16H19NO2S, MW:289.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Epelmycin E | Epelmycin E, CAS:76264-93-2, MF:C42H53NO16, MW:827.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodological Framework for Environmental Bioavailability Assessment

The following workflow outlines a comprehensive approach for assessing contaminant bioavailability in environmental systems, integrating both chemical and biological assessment tools:

Implications for Environmental Risk Assessment and Remediation

Incorporating bioavailability considerations into contaminated land risk assessment has become increasingly important for realistic hazard evaluation and efficient remediation [5]. The development of analytical tools for measuring bioavailability and bioaccessibility represents an active research frontier, with chemical extraction methods frequently correlated with biological endpoints like biodegradation [5]. A significant challenge remains that bioavailability is organism-specific, making universal chemical extraction techniques difficult to establish [5].

Understanding bioavailability processes enables more accurate exposure assessments in ecological risk evaluations, potentially reducing unnecessary cleanup costs while maintaining protective outcomes [2]. Contemporary risk assessment practice often incorporates bioavailability as an adjustment factor accounting for a chemical's ability to be absorbed, but frequently fails to transparently identify and explain assumptions regarding individual bioavailability processes [2]. Improving this aspect requires greater mechanistic understanding of bioavailability processes and evaluation of various tools for providing information on these processes [2].

For regulatory applications, particularly in the pharmaceutical sector, bioequivalence testing ensures that generic drug products provide comparable systemic exposure to reference products, with specific requirements for summary tables documenting study designs, statistical analyses, and formulation characteristics [13]. These standardized approaches facilitate regulatory review while ensuring therapeutic equivalence through demonstrated bioavailability equivalence [13].

The concept of bioavailability processes provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex physical, chemical, and biological interactions that determine contaminant exposure in environmental systems and drug availability in pharmacological contexts. This process-based approach moves beyond simplistic definitions to recognize the dynamic, multi-faceted nature of bioavailability across different organisms, exposure routes, and environmental conditions. Advances in both environmental and pharmaceutical bioavailability research continue to refine our understanding of these critical processes, enabling more accurate risk assessments, more effective remediation strategies, and more reliable therapeutic interventions. The ongoing development of standardized testing methodologies, coupled with mechanistic research on binding, transport, and metabolic processes, will further enhance our ability to predict and manage contaminant exposure and drug efficacy across diverse applications.

Understanding the environmental fate of contaminants—their transport, transformation, and ultimate degradation—is fundamental to assessing ecological risks and developing effective remediation strategies. The behavior of a chemical in the environment is not random; it is governed by a set of intrinsic physicochemical properties that determine its interactions with biological systems and abiotic matrices [14]. Among these, solubility, volatility, and reactivity are critical primary properties that exert a controlling influence on a contaminant's bioavailability, persistence, and potential toxicological impacts [15] [14]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of these core properties, framing them within the context of environmental fate and bioavailability research for a scientific audience. Accurate determination of these properties enables researchers to predict contaminant partitioning, design robust experimental protocols, and inform regulatory decisions for chemical alternatives and drug development.

Fundamental Properties and Their Environmental Significance

Aqueous Solubility

Aqueous solubility is defined as the maximum concentration of a chemical that can dissolve in water at a given temperature and pressure. It is a direct measure of a substance's hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity and is perhaps the single most important property influencing a contaminant's environmental fate [16]. High solubility generally promotes mobility in groundwater and surface water, increasing the potential for widespread dispersion and aquatic exposure [15] [14]. Conversely, low solubility limits dissolved concentrations but can lead to the formation of separate-phase liquids (NAPLs) or solid precipitates, which act as long-term secondary sources of contamination [17].

The environmental impact of solubility is profound. Even when solubility is low, the dissolved fraction may be sufficient to degrade water quality and pose threats to ecosystems and human health [17]. In bioavailability and toxicity studies, exposing test organisms to concentrations exceeding a chemical's water solubility can confound test interpretation, as the test system may include undissolved chemical or micro-droplets, leading to inaccurate hazard assessments [16].

Volatility

Volatility describes the tendency of a substance to transfer from its liquid or solid phase into the vapor phase. It is quantitatively described by vapor pressure and Henry's Law constant (KH). Vapor pressure is the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases at a given temperature. Henry's Law constant is the ratio of a compound's vapor pressure to its water solubility (KH = Pv/S), defining its partitioning between the air and water phases [14].

Volatility dictates the potential for atmospheric transport of contaminants. Chemicals with high volatility, such as dichloromethane, are prone to evaporate from soil and water surfaces, leading to inhalation exposure risks and long-range transport through the atmosphere [18]. The Henry's Law constant specifically indicates whether a contaminant released to water will volatilize into the air (high KH) or remain dissolved (low KH) [15] [14]. This partitioning influences the selection of remediation techniques, such as soil vapor extraction or air sparging, for volatile organic compounds.

Chemical Reactivity

Chemical reactivity encompasses a contaminant's propensity to undergo abiotic chemical transformations through processes such as hydrolysis, oxidation, reduction, and photolysis [15]. These processes can break down contaminants into simpler, often less harmful, daughter products or, in some cases, transform them into more toxic compounds. Reactivity is influenced by molecular structure, presence of functional groups, and environmental conditions such as pH and the presence of catalysts [14].

In the environment, reactivity directly determines a contaminant's persistence. Highly reactive compounds may degrade rapidly, limiting their spatial and temporal impact. In contrast, persistent compounds, such as many chlorinated solvents and certain halogenated organics, resist degradation and can accumulate in environmental compartments, leading to long-term exposure risks [15] [18]. Understanding reactivity is therefore crucial for predicting the lifetime of contaminants and for designing advanced chemical or photochemical remediation treatments.

Integrated Property Influence on Environmental Fate

These three properties do not act in isolation; they interact to determine a contaminant's overall environmental behavior. The following diagram illustrates the interconnected influence of solubility, volatility, and reactivity on key environmental fate processes.

This interplay means that a holistic risk assessment must consider all properties simultaneously. For instance, a contaminant with low solubility but high volatility may still become widely distributed through atmospheric pathways. Similarly, high reactivity might reduce a contaminant's persistence, but only if it is bioavailable or in a chemical state that allows the reaction to proceed.

Quantitative Data and Property Ranges

The following tables summarize typical values and measurement methods for these critical properties across a range of common environmental contaminants, providing a reference for researchers.

Table 1: Property Ranges and Environmental Significance of Key Contaminant Classes

| Contaminant Class/Example | Solubility (mg/L) | Vapor Pressure (kPa) | Key Reactivity | Primary Environmental Fate Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phthalates (e.g., DEHP) [19] | Very Low (< 0.01) | Low | Resists hydrolysis | Sorbs strongly to solids; persists in sludge/biosolids; potential for bioaccumulation. |

| Pharmaceuticals (e.g., Sertraline) [19] | Variable (Low-Moderate) | Very Low | Biodegradation primary pathway | Mobile in water if soluble; removal dependent on wastewater treatment. |

| Chlorinated Solvents (e.g., Dichloromethane) [18] | Moderate (~1,380) | High (58 kPa at 25°C) | Hydrolyzes slowly; can be oxidized | High potential for volatilization & groundwater plume formation. |

| Neonicotinoids [19] | Moderate to High | Low to Moderate | Photolysis & biodegradation | Mobile in soil & water; widespread surface water contamination. |

| Personal Care Products (e.g., Triclosan) [19] | Low | Low | Photodegradable | Found in biosolids; can persist in sediments. |

Table 2: Standard Methodologies for Property Determination

| Property | Key Standardized Methods | Applicability & Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solubility | Shake-Flask (OECD 105) [16]: For solubility > 10â»âµ g/L. Agitation of excess chemical with water, separation, and analysis.Column Elution (OECD 105) [16]: For low-solubility solids. Water passed through a column packed with chemical-coated inert support.Slow-Stir Method [16]: For volatile, hydrophobic liquids. Minimizes emulsion formation; long equilibration times (weeks). | Shake-flask unsuitable for very low-solubility or volatile compounds due to emulsions and losses. Column elution not suitable for liquids. Slow-stir addresses this gap but is not yet an OECD guideline. |

| Volatility | Vapor Pressure (OECD 104) [14]: Effusion methods (e.g., Knudsen) for low VP, dynamic methods for higher VP.Henry's Law Constant: Determined experimentally or calculated from ratio of vapor pressure to solubility. | Measurement requires careful temperature control. For KH, experimental determination is preferred over calculated values for accuracy. |

| Reactivity | Hydrolysis (OECD 111) [14]: Determines rate of chemical breakdown in water at different pHs.Photolysis (OECD 316) [14]: Determines direct and indirect photodegradation in water/air. | Complex to simulate real environmental conditions (e.g., sensitizers in photolysis). Data often requires extrapolation to field conditions. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Accurate determination of these properties, particularly for "difficult-to-test" substances (e.g., those with very low solubility or high volatility), requires specialized methodologies. Below are detailed protocols for key advanced techniques.

The Slow-Stir Method for Determining Low Aqueous Solubility

The slow-stir method is designed to measure the water solubility of volatile, hydrophobic liquid compounds, filling a gap in existing standardized guidelines [16].

Principle: The method uses a sealed, headspace-minimized vessel where an excess of the test substance is slowly stirred with water. The minimal agitation prevents the formation of emulsions, a critical drawback of the shake-flask method for liquids. The system is allowed to reach equilibrium over time, which for extremely low-solubility substances (< 10 µg/L) may take several weeks. The dissolved concentration is measured by sampling the aqueous phase from a bottom port [16].

Detailed Procedure:

- Apparatus Setup: A glass vessel (1-20 L capacity) with a sampling spigot at the bottom is used. The vessel is filled with reagent-grade water (e.g., Milli-Q), leaving minimal headspace. The system is temperature-controlled (e.g., 20°C ± 0.5°C).

- Dosing: The test substance (liquid, density < 1 g/mL) is added to the water surface in excess, typically at a loading 3-4 orders of magnitude greater than the expected solubility.

- Equilibration: The vessel is sealed and stirred with a magnetic stirrer. The stirring speed is set to create a minimal vortex—just enough to create a slight dimple (< 0.5 cm) on the water surface—to avoid emulsification.

- Sampling and Analysis: Water samples are periodically withdrawn directly from the bottom sampling spigot using gas-tight syringes or other techniques to minimize volatile losses. The samples are extracted and analyzed using compound-specific analytical methods (e.g., GC-MS, LC-MS). Equilibrium is considered reached when consecutive measurements show a stable concentration.

- Quality Control: Use of replicate vessels and blank controls is essential. The method has demonstrated inter-laboratory reproducibility with relative standard deviations of 20% or less for compounds like n-hexylcyclohexane [16].

The workflow for this method, from setup to analysis, is outlined below.

Headspace Gas Chromatography for Volatility and Solubility

Volatile-tracer assisted headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC) is a sophisticated technique used to determine the solubility of low-volatility organic compounds and can also be applied to study volatility directly [17].

Principle: For solubility determination, a volatile tracer of known partitioning behavior is added to the organic solute. This mixture is then added incrementally to water in a closed headspace vial. After equilibrium, the headspace concentration of the volatile tracer is measured by GC. A plot of the GC signal versus the organic solute concentration will show a distinct change in slope at the point where the water becomes saturated with the organic solute, thereby identifying its solubility [17].

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: A series of closed headspace vials are prepared with a fixed volume of water. Increasing amounts of the low-volatility organic solute, spiked with a known concentration of a volatile tracer (e.g., toluene), are added to the vials.

- Equilibration: The vials are equilibrated at a constant temperature in an automated headspace sampler.

- HS-GC Analysis: The headspace of each vial is automatically sampled and injected into a gas chromatograph. The peak area of the volatile tracer is measured.

- Data Analysis: The GC signal (tracer peak area) is plotted against the concentration of the low-volatility solute added. The intersection point of the two linear segments of the plot, representing the under-saturated and over-saturated states, corresponds to the aqueous solubility of the solute.

- Advantages: This method is advantageous for its in-situ sampling, which avoids errors associated with temperature changes during sample transfer in conventional methods. It is particularly useful for compounds with very low solubility [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental determination of contaminant properties relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items for a modern environmental chemistry laboratory.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item/Category | Specification/Example | Primary Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Water | Milli-Q (18.2 MΩ·cm), glass-distilled, double-distilled. | Serves as the aqueous matrix for solubility, hydrolysis, and toxicity testing; minimizes interference from impurities. |

| Inert Support Phases | Diatomaceous earth, glass beads, chromatographic silica. | Used as a solid support for coating low-solubility solid compounds in the column elution method for solubility. |

| Volatile Tracers | Toluene, methanol [17]. | Acts as a proxy for measuring partitioning and solubility of low-volatility compounds in headspace GC methods. |

| Chemical Stabilizers | Amylene (for Dichloromethane) [18], other antioxidants. | Added to stock solutions or test substances to prevent chemical degradation (e.g., by air or moisture) during storage or long-term tests. |

| Reference Compounds | n-Hexylcyclohexane [16], Dodecahydrotriphenylene [16]. | Used for method validation and inter-laboratory calibration of techniques like the slow-stir and column elution methods. |

| Sorption Media | Activated carbon, clay minerals (e.g., zeolites) [20]. | Used in absorption studies and decontamination protocols to immobilize and concentrate contaminants from liquid or gaseous phases. |

| Headspace Vials & Septa | Certified glass vials with PTFE/silicone septa. | Ensure a gas-tight seal for volatile compound analysis, preventing losses and ensuring accurate headspace concentration measurements. |

| 6,7-Dichloroquinoline-5,8-dione | 6,7-Dichloroquinoline-5,8-dione, CAS:6541-19-1, MF:C9H3Cl2NO2, MW:228.03 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tetrahydroaldosterone-3-glucuronide | Tetrahydroaldosterone-3-glucuronide|C27H40O11|RUO | Tetrahydroaldosterone-3-glucuronide is a key human aldosterone metabolite for endocrine research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

The critical contaminant properties of solubility, volatility, and reactivity form the foundational triad for predicting environmental fate and bioavailability. As demonstrated, these properties are interconnected, dictating whether a contaminant will remain localized or become dispersed, persist for decades or degrade rapidly, and ultimately whether it will pose a risk to living organisms. The accurate determination of these properties, especially for difficult-to-test substances, remains a central challenge in environmental chemistry. Continued refinement of advanced experimental protocols, such as the slow-stir and volatile-tracer assisted HS-GC methods, is essential for generating high-quality data. Integrating this physicochemical property data with an understanding of site-specific biogeochemical conditions and biological systems is the cornerstone of robust environmental risk assessment and the development of effective mitigation and remediation strategies, ultimately protecting ecosystem and human health.

The environmental fate, mobility, and ultimate biological impact of contaminants are not solely determined by their inherent chemical properties. Rather, these pathways are profoundly modified by the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of the environmental matrices with which they interact—namely soils, sediments, and aquifers [2]. The concept of "bioavailability processes" provides a critical framework for understanding these interactions, defined as the individual physical, chemical, and biological events that determine the exposure of plants and animals to chemicals associated with soils and sediments [2]. Within the context of contaminant bioavailability research, appreciating the role of these environmental modifiers is paramount for developing accurate risk assessments, effective remediation strategies, and predictive models for contaminant transport and fate.

This technical guide synthesizes the current understanding of how soil, sediment, and aquifer characteristics act as fundamental modifiers of contaminant bioavailability. It outlines the key processes and properties that govern these interactions, supported by quantitative data and experimental approaches relevant to researchers and scientists working in environmental fate and transport.

Conceptual Framework: Bioavailability Processes

Bioavailability has been defined in various discipline-specific ways, but a consensus view recognizes it as a measure of the potential for a contaminant to enter ecological or human receptors, specific to the receptor, route of entry, time of exposure, and the containing matrix [2]. The National Research Council formalized a process-based approach, identifying a sequence of critical interactions illustrated in the following diagram:

Figure 1: Bioavailability Processes for Contaminants in Soils and Sediments (Adapted from NRC, 2003 [21]). Processes A through E represent the sequence of physical, chemical, and biological events that determine the exposure of an organism to a soil- or sediment-bound contaminant.

As shown in Figure 1, a contaminant must typically be released from the solid phase (Process A, B) and transported to an organism (Process C) before it can interact with a biological membrane (Process D) and be absorbed (Process E) [21]. The characteristics of the environmental matrix exert primary control over the initial release and transport processes.

Soil and Sediment Characteristics as Environmental Modifiers

Soils and sediments are complex ecosystems comprising mineral matter, organic material, and living organisms. Soils are typically well-aerated upland materials, while sediments are saturated materials often found in aquatic environments with potentially anoxic conditions [21]. This fundamental difference in aeration status leads to significant variations in their modifying effects.

Key Material Properties and Processes

The following table summarizes the primary soil and sediment properties that modify contaminant bioavailability, along with their mechanisms of influence and representative quantitative values.

Table 1: Key Properties of Soils and Sediments Modifying Contaminant Bioavailability

| Property/Process | Description & Mechanism | Impact on Bioavailability | Representative Values / Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Organic Matter (SOM) | Non-uniform, amorphous organic polymers that strongly sorb hydrophobic organic compounds (HOCs) and ionizable chemicals via partitioning and specific interactions [22]. | Reduces bioavailability of HOCs and ionizable organic chemicals (IOCs); dominant sorbent in most soils [22]. | Sorption of polar chemicals is still dominated by interactions with SOM. KOC (organic carbon-water partition coefficient) is a key predictive parameter [22]. |

| Clay Minerals | Secondary layered aluminosilicates with high specific surface area and charge; sorb contaminants via ion exchange and surface complexation [21]. | Significantly influences sorption of ionic and polar contaminants, especially when SOM is low. Clay content and type (e.g., montmorillonite vs. kaolinite) are critical [21]. | Key component of the "composite of inherited and authogenic material" in soils/sediments [21]. |

| Metal Oxides (Fe, Mn, Al) | Authogenic (formed in place) amorphous or crystalline oxides/hydroxides; sorb contaminants, especially metals, via surface complexation and co-precipitation [23]. | Major sink for heavy metals (e.g., Pb, Zn, As). Their stability under changing pH and redox conditions controls metal bioavailability [23]. | Pb²⺠adsorbed to Fe and Mn (hydr)oxides can be comparatively inert, but may be mobilized by changes in chemistry [23]. |

| pH | Master variable affecting surface charge of particles, speciation of IOCs, and solubility of metallic cations and anions [24]. | Lower pH increases bioavailability of cationic metals (e.g., Cd²âº, Pb²âº) but decreases bioavailability of oxyanions (e.g., CrO₄²â», AsO₄³â») [24]. | Critical for IOCs; prediction of pH-dependent sorption remains problematic [22]. |

| Redox Potential (Eh) | Measure of electron activity in soil/sediment solution, governing biogeochemical transformations [24]. | Anaerobic conditions in sediments can reduce Fe/Mn oxides, releasing associated metals. Can also drive microbial degradation of organic contaminants [21]. | Creates the contrasting physical environments between oxic soils and often anoxic aquatic sediments [21]. |

| Non-Extractable Residues (NER) | Contaminant fraction strongly sequestered within the soil/sediment matrix, inaccessible to mild extraction [22]. | Can significantly reduce bioavailability. "Xenobiotic NER" may be a hidden hazard, while "Biogenic NER" from microbial assimilation is considered a safe sink [22]. | Formed during the turnover of organic chemicals; a 'black box' in current risk assessment [22]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Modifiers

Accurate assessment of bioavailability requires standardized methodologies to characterize these environmental modifiers. The following protocols are essential.

Protocol 1: Determination of Sorption Isotherms

- Objective: To quantify the partitioning of a contaminant between the solid and aqueous phases at equilibrium.

- Procedure:

- A series of centrifuge tubes containing a fixed mass of soil/sediment is prepared with varying initial concentrations of the contaminant in a background electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.01 M CaClâ‚‚).

- Tubes are sealed and agitated for a predetermined period (typically 24-48 hours) to reach equilibrium, at a constant temperature.

- The solid and liquid phases are separated by centrifugation and filtration (e.g., 0.45 μm membrane filter).

- The equilibrium concentration in the aqueous phase (Câ‚‘) is measured using appropriate analytical techniques (e.g., GC-MS, HPLC, ICP-MS).

- The amount sorbed to the solid (Qâ‚‘) is calculated from the difference between the initial and equilibrium aqueous concentrations.

- Data Analysis: Data is fitted to models such as the Linear model (Qâ‚‘ = Kd × Câ‚‘), Freundlich model (Qâ‚‘ = Kf × Câ‚‘^â¿), or Langmuir model to derive sorption parameters [24]. The organic carbon-normalized distribution coefficient (KOC = Kd / fOC) is calculated where fOC is the fraction of organic carbon.

Protocol 2: Sequential Extraction for Metal Speciation

- Objective: To operationally define the geochemical fractions of a metal contaminant (e.g., exchangeable, bound to carbonates, Fe/Mn oxides, organic matter, residual).

- Procedure:

- A soil/sediment sample is subjected to a series of increasingly strong chemical extractions.

- Step 1 (Exchangeable): Extract with MgClâ‚‚ solution (pH 7.0).

- Step 2 (Carbonate-bound): Extract the residue from Step 1 with sodium acetate (pH 5.0).

- Step 3 (Fe/Mn Oxide-bound): Extract the residue from Step 2 with hydroxylamine hydrochloride in acetic acid (pH 2.0).

- Step 4 (Organic Matter-bound): Extract the residue from Step 3 with hydrogen peroxide and ammonium acetate.

- Step 5 (Residual): Digest the final residue with strong acids (HNO₃, HF, HClO₄).

- Data Analysis: The metal concentration in each extract is measured. The bioavailability and potential mobility typically decrease from Step 1 to Step 5 [23]. This provides a more realistic estimate of bioavailable metal pools than total concentration.

Aquifer Characteristics and Contaminant Transport

In groundwater systems, aquifer properties control the advection, dispersion, and transformation of dissolved contaminant plumes, thereby influencing the concentration to which downstream receptors are exposed [24].

Key Aquifer Properties and Classification

Aquifers are classified based on the water table configuration and subsurface confinement, which directly affects contaminant transport pathways and vulnerability.

Figure 2: Classification and Key Characteristics of Aquifers [25]. Confined and unconfined aquifers differ fundamentally in their hydrology and vulnerability, influencing contaminant transport and fate.

The physical and hydraulic properties of the aquifer matrix are primary modifiers of contaminant transport, as quantified in the table below.

Table 2: Key Aquifer Properties Modifying Contaminant Transport and Bioavailability

| Property | Definition & Description | Impact on Contaminant Transport & Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Porosity (n) | The volume of void spaces (pores) divided by the total volume of the formation [25]. | Primary Porosity: Determines the volume available for contaminant storage in groundwater. Secondary Porosity (fractures, joints) can create preferential flow paths, leading to rapid, unpredictable contaminant migration [24] [25]. |

| Hydraulic Conductivity (K) | The ease with which a fluid (water) can move through pore spaces or fractures of the aquifer [25]. | Governs the average linear velocity of groundwater (v = Ki/n), and thus the speed of contaminant plume migration (advection). Higher K values lead to faster plume advancement [24]. |

| Transmissivity (T) | The rate at which water is transmitted horizontally through a unit width of the full saturated thickness of the aquifer under a unit hydraulic gradient (T = K × b) [25]. | An integrated measure of an aquifer's ability to transmit water. Contaminants will reach receptors more quickly in aquifers with high transmissivity [26]. |

| Storativity (S) | The volume of water released from storage per unit surface area of aquifer per unit decline in hydraulic head [25]. | In unconfined aquifers, this is primarily the drainable porosity. Influences how quickly a contaminant plume may spread or dilute upon entering the aquifer. |

| Geochemical Conditions | The pH, redox potential, and presence of organic matter/minerals in the subsurface [24]. | Aquifer geochemistry controls contaminant reactions en route to a receptor, including sorption, precipitation, and biodegradation, thereby reducing the bioavailable concentration at the point of exposure [24]. |

Experimental and Modeling Approaches for Aquifers

Geophysical Characterization: Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) is a key field method for characterizing aquifer architecture. It involves introducing a direct current into the ground between two current electrodes and measuring the resulting potential difference at two potential electrodes [26]. The apparent resistivity of the subsurface is calculated, which correlates with lithology (e.g., low resistivity in clay-rich layers, high resistivity in consolidated rock) and pore water conductivity. This allows for the non-invasive imaging of aquifer boundaries, thickness, and heterogeneity, which are critical for modeling contaminant transport pathways [26] [25].

Mathematical Modeling of Contaminant Transport: The advection-dispersion-reaction equation (ADRE) is the foundational model for predicting contaminant movement in groundwater [24]. For one-dimensional flow: [ \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = -v \frac{\partial C}{\partial x} + D \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2} + \sum R ] Where ( C ) is contaminant concentration, ( t ) is time, ( v ) is average linear groundwater velocity, ( x ) is distance, ( D ) is the dispersion coefficient, and ( \sum R ) is a term representing all reactions (e.g., sorption, biodegradation). Sorption is often simplified using a linear isotherm (( Q = K_d C )), which is incorporated into a retardation factor (R) that slows the advance of the contaminant plume relative to the groundwater velocity [24]. The U.S. EPA develops and employs models like MT3D and BIOPLUME III to simulate these complex processes [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Bioavailability and Transport Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Passive Samplers (e.g., SPME, POMs) | Devices that passively accumulate contaminants from water or porewater, providing a direct measure of the chemically available (bioavailable) concentration [22]. |

| Background Electrolyte Solutions (e.g., CaClâ‚‚, NaCl) | Used in sorption experiments to maintain a constant ionic strength, mimicking natural soil water conditions and ensuring reproducible results. |

| Chemical Extractants (e.g., Mild Solvents, Chelating Agents) | Used in sequential extraction protocols or as mild chemical proxies to estimate the bioavailable fraction of contaminants (e.g., EDTA for trace metals) [22]. |

| Isotope-Labeled Contaminants (e.g., ¹â´C, ¹³C) | Allow for precise tracking of contaminant transformation, mineralization, and incorporation into non-extractable residues (NER) in fate studies, crucial for distinguishing biogenic from xenobiotic NER [22]. |

| Geophysical Equipment (e.g., Resistivity Meter, GPR) | For non-invasive subsurface characterization. Electrical Resistivity meters image aquifer lithology, while Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) can delineate shallow stratigraphy and water table positions [26] [25]. |

| Reactive Transport Models (e.g., MT3D, MODFLOW) | Numerical software that couples groundwater flow with geochemical reactions to predict the spatial and temporal evolution of contaminant plumes, incorporating processes like sorption and biodegradation [24] [27]. |

| Pyrrolomycin B | Pyrrolomycin B, CAS:79763-00-1, MF:C11H6Cl4N2O3, MW:356.0 g/mol |

| TCS PIM-1 1 | TCS PIM-1 1, MF:C18H11BrN2O2, MW:367.2 g/mol |

The characteristics of soils, sediments, and aquifers are not passive background conditions but active and dynamic modifiers of contaminant fate and bioavailability. The properties of these environmental matrices—from the molecular-scale interactions governed by soil organic matter and pH to the aquifer-scale dynamics controlled by porosity and hydraulic conductivity—fundamentally alter the trajectory and biological impact of environmental contaminants. A rigorous, process-based understanding of these modifiers, supported by the experimental and modeling tools outlined in this guide, is essential for advancing predictive capabilities in contaminant bioavailability research. Integrating this knowledge into risk assessment and remediation decision-making ensures that interventions are based on the truly bioavailable contaminant fraction, leading to more scientifically defensible and cost-effective environmental management.

The continuous release of pharmaceuticals, personal care products (PCPs), and industrial chemicals into the environment represents a significant challenge for environmental scientists and regulators. These contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) are characterized by their continuous introduction into ecosystems, pseudo-persistence, and potential to cause biological effects at low concentrations. Global pharmaceutical consumption is rising with the growing and ageing human population and more intensive food production [28]. Similarly, the increasing availability and diversity of PCPs has resulted in higher loading of these compounds into wastewater systems [29]. These substances persist in the environment and demonstrate adverse effects on human, wild, and marine life, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of their environmental fate and bioavailability [29].

Understanding the environmental fate of these contaminants is crucial for assessing ecological risks. These compounds typically are designed to have biological effects at low doses, acting on physiological systems that can be evolutionarily conserved across taxa [28]. The core challenge in environmental bioavailability research lies in predicting how these substances move through environmental compartments, transform over time, and become available to organisms through various exposure pathways. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the major contaminant classes, their environmental behavior, and the advanced methodologies used to study their fate in the context of modern environmental chemistry.

Pharmaceutical Contaminants

Human and veterinary pharmaceuticals enter the environment through multiple pathways. When medications are consumed, parent compounds and metabolites are excreted into wastewater systems or directly into the environment [28]. Significant quantities can also be emitted from manufacturing sites, particularly in lower income countries [28]. Depending on their physico-chemical properties, compounds can be degraded, partition to water or solid phases including biosolids, or enter aquatic or terrestrial environments [28]. Veterinary drugs may be released directly through excreted treatments or indirectly via predation or scavenging of medicated animals [28].

A key characteristic of pharmaceutical contaminants is their "pseudo-persistence" – while individual molecules may degrade, the continuous release of these compounds into the environment creates constant exposures for organisms, even to relatively degradable compounds [28]. Current wastewater treatment plants are often ineffective at completely removing these substances, leading to their discharge into surface waters and subsequent distribution throughout aquatic ecosystems.

Key Pharmaceutical Compounds and Their Properties

Table 1: Key Pharmaceutical Compounds and Their Environmental Properties

| Compound | Therapeutic Class | Persistence | Key Environmental Concerns | Bioaccumulation Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbamazepine | Anticonvulsant | Persists in soil unchanged for at least 40 days; taken up into crop plants [28] | Bioaccumulation in food webs | High potential for plant uptake [28] |

| Fluoxetine | Antidepressant (SSRI) | Minimal degradation in sewage or soil over many months [28] | Behavioral, physiological alterations in aquatic organisms | Bioconcentration factor (BCF) >1000 in freshwater mussels [28] |

| Diclofenac | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory | Moderate persistence | Toxicity to raptors; histological alterations in fish | Zero-order metabolism in raptors increases susceptibility [28] |

| Sulfamethazine | Antibiotic | Mobile in soil systems | Promotion of antibiotic resistance; disruption of microbial communities | Uptake documented in plants from manure-amended soil [30] |

Experimental Approaches for Fate Assessment

Water-Sediment Systems: The OECD 308 guideline provides a standardized method for investigating the biodegradation of pharmaceuticals in water/sediment systems [30]. This test system examines the rate and pathway of degradation of a test substance in a water-sediment system under aerobic conditions, allowing determination of the distribution between water and sediment phases and the formation of transformation products. The system is maintained in the dark at constant temperature, with periodic analysis of the water and sediment phases for the test substance and its transformation products.

Soil Sorption Studies: Sorption coefficients (Kd) are determined through batch equilibrium experiments where soil is mixed with a solution containing the pharmaceutical compound [30]. After reaching equilibrium, the concentration in the solution phase is measured, and the sorbed concentration is calculated by difference. Factors such as pH and cation exchange capacity significantly influence sorption, particularly for ionizable pharmaceuticals [30]. These studies are crucial for predicting the mobility of pharmaceuticals in soil systems and potential groundwater contamination.

Uptake Studies in Biota: Bioconcentration factors (BCF) are determined through controlled laboratory exposures where organisms such as fish are maintained in water containing the pharmaceutical [28]. The uptake of the substance into the organism's tissues is measured over time, along with depuration in clean water. For example, studies with fluoxetine have demonstrated pH-dependent bioaccumulation in Japanese medaka, highlighting the importance of environmental conditions on bioavailability [30].

Personal Care Products (PCPs)

Definition and Classification

Personal care products constitute a broad category of self-care products used for personal hygiene, cleaning, grooming, and beautification [29]. These include hair and skin care products, baby care products, UV blocking creams, facial cleansers, insect repellents, perfumes, fragrances, soap, detergents, shampoos, conditioners, and toothpaste [29]. PCPs represent a significant source of environmental contaminants due to their widespread use and continuous discharge into wastewater systems.

The emerging contaminants from PCPs are grouped into several key classes: alkylphenol polyethoxylates, antimicrobials, bisphenols, cyclosiloxanes, ethanolamines, fragrances, glycol ethers, insect repellents, parabens, phthalates, and UV filters [29]. These compounds enter the environment primarily through residential use, with emissions occurring via wastewater systems, surface runoff, and volatilization during application.

Major PCP Compounds and Environmental Behavior

Table 2: Major Personal Care Product Compounds and Their Environmental Properties

| Compound/Class | Primary Use | Environmental Fate | Ecological Concerns | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phthalates (DEHP, DBP, BBP) | Plasticizers in fragrance carriers, nail polishes | Contaminate indoor air; persistent in dust [29] | Endocrine disruption; reproductive effects | Banned or restricted in EU and US [29] |

| UV Filters (e.g., TiO2) | Sunscreen, product stabilization | Persistent; estimated daily dermal exposure 2.8-21.4 mg/person/day [29] | Effects on aquatic organisms; bioaccumulation | 35% of manufactured TiO2 used in PCPs [29] |

| Triclosan | Antimicrobial agent | Persistent despite usage limitations; detected in 45% of US soaps [29] | Antibiotic resistance; endocrine disruption | Limited by US-FDA but still prevalent [29] |

| Fragrances (e.g., polycyclic musks) | Perfumes, scented products | Persistent; bioaccumulative | Endocrine disruption; chronic toxicity | Often not fully disclosed on labels [29] |

| DEET (N,N-diethyltoluamide) | Insect repellent | Ubiquitous in aquatic environments; inhibits feeding in insects [31] | Effects on non-target aquatic organisms [31] | Widely used with limited environmental regulation |

Analytical Methodologies for PCP Detection

Sample Preparation and Extraction: Solid-phase extraction (SPE) is commonly employed for concentrating PCPs from water samples, while pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) and ultrasonic extraction are used for solid samples such as sediments and biosolids [29]. The complexity of PCP mixtures necessitates efficient clean-up procedures to remove interfering matrix components, often using gel permeation chromatography or silica-based adsorbents.

Instrumental Analysis: Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is the primary technique for determining most PCPs in environmental samples due to its high sensitivity and selectivity [29]. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is preferred for volatile and semi-volatile compounds such as fragrances and cyclosiloxanes. The analysis of inorganic PCP components like titanium dioxide requires techniques such as inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

Bioanalytical Tools: Bioassays are increasingly used to assess the cumulative effects of complex PCP mixtures. Yeast estrogen screen (YES) and other receptor-based assays detect endocrine-disrupting activity, while the ToxCast program employs high-throughput screening to characterize bioactivity profiles of PCP ingredients [29].

Industrial Chemicals

Major Classes and Applications

Industrial chemicals encompass a wide range of substances used in manufacturing processes, consumer products, and specialized applications. While the search results provided limited specific information on industrial chemicals, they are known to include plasticizers (e.g., bisphenol A), flame retardants, surfactants, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). These substances enter the environment through industrial discharges, product use, and waste disposal.

Bisphenol A (BPA), widely used in plasticizers, paints, heat stabilizers, and many consumer products including food containers and medical equipment, serves as a representative example of industrial chemical contaminants [31]. Many in vitro assays and animal tests have verified the adverse impacts of BPA on metabolic, immune and neurological systems [31].

Modeling Fate and Transport

Advanced modeling approaches are essential for predicting the behavior of industrial chemicals in the environment. A comprehensive three-dimensional hydrodynamic-eutrophication-risk assessment model has been developed to understand the fate and transport of emerging contaminants in multi-compartments and their interactions with other general water quality state variables [31]. These models simulate contaminants in four environmental compartments: bulk water and suspended solids in the water column, and pore water and sediments in the sediment layer [31].

The modeling approach couples hydrodynamic processes with water quality parameters and contaminant fate, allowing assessment of both direct and indirect impacts on contaminant distribution. For instance, models have demonstrated that BPA and DEET are predominately distributed in the dissolved phase in the water column but in the sorbed phase in the sediment layer [31]. This compartmental distribution significantly influences their bioavailability and potential ecological risks.

Environmental Fate and Bioavailability Processes

Key Fate Processes

The environmental fate of contaminants is governed by numerous processes including partitioning, transformation, and transport. Key processes include:

- Sorption/Desorption: Controlled by the chemical properties of the contaminant and environmental characteristics such as organic carbon content and pH. Cationic compounds may become bound to negatively charged clay particles, affecting their bioavailability [28].

- Biodegradation: Microbial breakdown of contaminants, which can vary significantly depending on redox conditions, microbial community composition, and contaminant structure.

- Photodegradation: Light-mediated transformation particularly important for surface waters and atmospheric compartments.

- Hydrolysis: Chemical breakdown mediated by water, which is pH-dependent and significant for certain chemical classes.

- Volatilization: Transfer to the atmospheric compartment, important for compounds with high vapor pressures.

These processes collectively determine the persistence, mobility, and ultimate fate of contaminants in environmental systems.

Multi-Compartment Distribution

Contaminants distribute across multiple environmental compartments, each with distinct characteristics affecting bioavailability. The distribution can be divided into several compartments: bulk water and suspended solids in the water column, pore water and sediments in the benthic layer [31]. Understanding this multi-compartment distribution is essential for accurate risk assessment, as the phase in which a contaminant resides significantly influences its potential for organismal exposure and uptake.

Diagram 1: Multi-compartment distribution and exposure pathways for environmental contaminants

Bioavailability Mechanisms

Bioavailability refers to the fraction of a contaminant that is available for uptake by organisms. Key mechanisms include:

- Bioconcentration: Uptake of contaminants directly from water across respiratory surfaces (gills, skin) [28].

- Bioaccumulation: Net accumulation from all environmental sources including water, sediment, and diet.

- Biomagnification: Increasing concentration at higher trophic levels due to dietary transfer.

- Trophic Dilution: Decreasing concentration at higher trophic levels, observed for some pharmaceuticals [28].

For many pharmaceuticals, direct uptake via gills appears more significant than dietary exposure in fish, contrary to traditional lipophilic contaminants [28]. This highlights the need for contaminant-specific assessment of bioavailability mechanisms.

Advanced Assessment Methodologies

Integrated Modeling Approaches

Modern contaminant fate assessment employs sophisticated modeling frameworks that integrate multiple environmental processes. The hydrodynamic-eutrophication-emerging contaminants-risk assessment (HEECRA) model represents an advanced approach that couples 3D hydrodynamic processes with eutrophication dynamics and contaminant fate [31]. This integrated model can track the spatiotemporal dynamics of emerging contaminants at high resolution and supplement monitoring campaigns.

These models simulate over 100 water quality state variables, including total nitrogen, total phosphorous, chlorophyll-a, nitrite, dissolved oxygen, total organic carbon, and total suspended solids, alongside contaminant distributions [31]. The correlation analysis between general water quality parameters and emerging contaminants under prevailing environmental conditions provides insights into indirect effects on contaminant behavior.

Experimental Workflow for Contaminant Fate Assessment

A systematic approach to contaminant fate assessment incorporates field monitoring, laboratory studies, and model integration as outlined in the following workflow:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for comprehensive contaminant fate assessment

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Contaminant Fate Studies

| Reagent/Methodology | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Systems | High-sensitivity quantification of pharmaceuticals and PCPs | Detection of antidepressants, antibiotics, UV filters in water matrices [29] |

| Passive Sampling Devices (e.g., POCIS, SPMD) | Time-integrated monitoring of waterborne contaminants | Measuring time-weighted average concentrations of hydrophilic and hydrophobic contaminants |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Internal standards for quantitative analysis | Correction for matrix effects and extraction efficiency in complex environmental samples |

| EML (Ecological Metadata Language) | Standardized data documentation | Creating detailed metadata for environmental data packages to ensure FAIR principles [32] |

| OECD Test Guidelines (308, 316) | Standardized fate testing protocols | Water-sediment degradation studies; bioaccumulation assessment in aquatic systems [30] |

| Bioanalytical Assays (e.g., YES, CALUX) | Effect-based screening for biological activity | Detection of endocrine-disrupting activity in complex environmental mixtures |

| 3D Hydrodynamic Models | Simulation of water movement and contaminant transport | Predicting spatiotemporal distribution of contaminants in reservoirs [31] |

Research Gaps and Future Directions