Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) in Biomedical Research: A Guide to Development, Application, and Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) in Biomedical Research: A Guide to Development, Application, and Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of SSDs, explores advanced methodological approaches and computational tools like the US EPA's SSD Toolbox, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for data-limited scenarios. The content further delves into validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different SSD approaches, highlighting their critical role in modern ecological risk assessment and the development of a precision ecotoxicology framework for biomedical and environmental safety applications.

Understanding Species Sensitivity Distributions: Core Concepts and Ecological Significance

Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) are statistical models used in ecological risk assessment (ERA) to extrapolate the results of single-species toxicity tests to a toxicity threshold considered protective of ecosystem structure and functioning [1] [2]. This approach uses the sensitivity of multiple species to a stressor, typically a chemical, to estimate the concentration that is protective of a predefined proportion of species in an ecosystem [3]. The SSD methodology has gained increasing attention and importance in scientific and regulatory communities since the 1990s as a practical tool for deriving environmental quality standards and for quantitative ecological risk assessment [1] [2] [3].

The core principle of an SSD is that the sensitivities of a set of species to a particular chemical or stressor can be described by a statistical distribution, often a log-normal distribution [4]. By fitting a cumulative distribution function to collected toxicity data (e.g., EC50 or LC50 values), it becomes possible to determine the concentration at which only a small, predetermined fraction of species (typically 5%) is expected to be affected [4] [3]. This value, known as the Hazard Concentration for p% of species (HCp), serves as a basis for establishing predicted no-effect concentrations (PNECs) in regulatory frameworks [4].

Core Principles and Methodology

Theoretical Foundation and Key Assumptions

The SSD approach operates on several fundamental assumptions that underpin its application in ecological risk assessment [3]:

- A sufficiently large number of species is used to construct a statistically robust sensitivity distribution.

- The selected species form a good representation of all species and ecological groups in the ecosystem, including different taxonomic groups and trophic levels.

- Protecting individual species is sufficient to protect the ecosystem. To strengthen this assumption, the use of exposure-effect data for "ecosystem-relevant" or "keystone" species is recommended.

The validity of these assumptions directly influences the reliability and protectiveness of the derived environmental thresholds.

Workflow for Developing an SSD

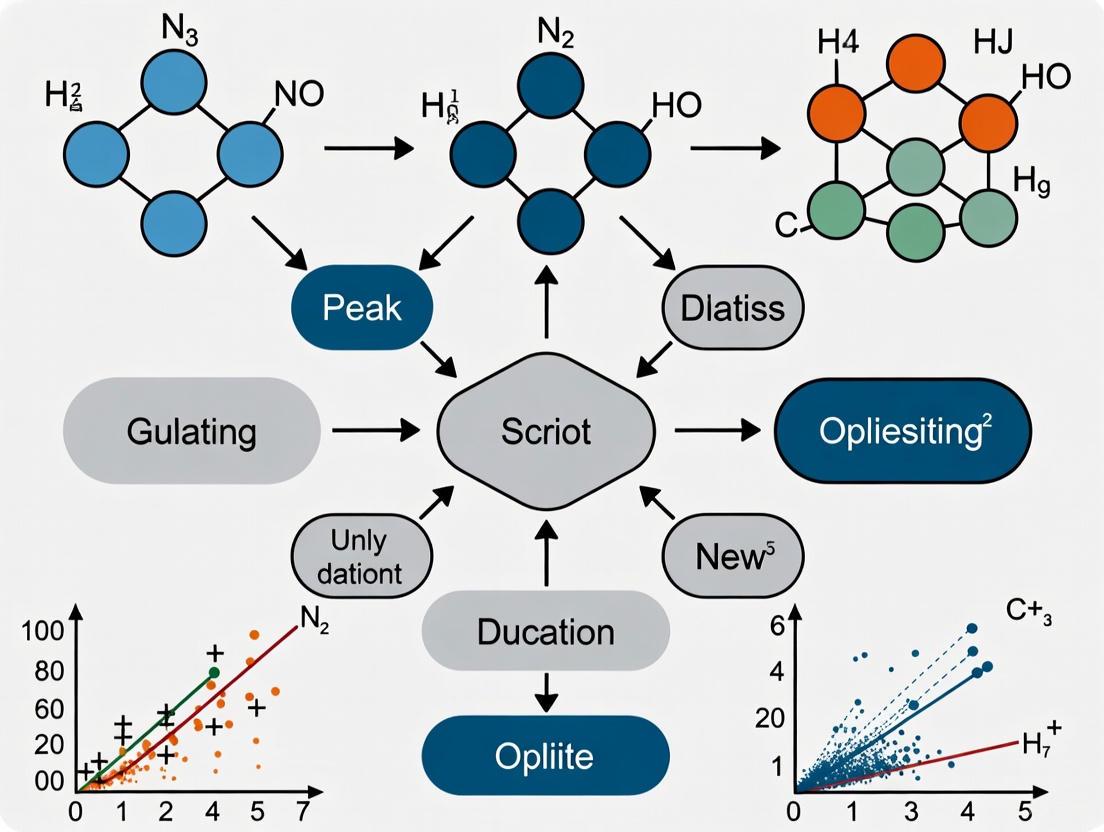

The process of developing and applying an SSD follows a structured workflow, illustrated below and detailed in the subsequent sections.

Data Requirements and Compilation

The first critical step is the collection and compilation of toxicity data. A robust SSD requires high-quality toxicity data (e.g., EC50, LC50, or NOEC values) for a suite of species that represent different taxonomic groups and trophic levels [3]. The data are typically gathered from standardized laboratory toxicity tests [5]. The number of species required is a subject of discussion, but generally, more species lead to a more reliable and robust distribution. The selection of species should aim to be ecologically relevant to the ecosystem being protected.

Statistical Derivation of Thresholds

Once compiled, the toxicity data are ranked from most to least sensitive and a statistical distribution (e.g., log-normal, log-logistic) is fitted to the data [4]. From this fitted distribution, the Hazard Concentration (HC) for a specific percentile of species is calculated. The most commonly used threshold is the HC5, which is the concentration estimated to affect 5% of the species in the distribution [1] [4]. A confidence interval is often calculated around the HC5 to quantify statistical uncertainty. The HC5 can then be used as a Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC) for regulatory purposes [4] [3].

Risk Characterization Using the Potentially Affected Fraction (PAF)

In addition to deriving a "safe" threshold, SSDs can be used for quantitative risk characterization via the Potentially Affected Fraction (PAF) [3]. For a given measured or predicted environmental concentration (PEC), the PAF represents the proportion of species for which that concentration exceeds their toxicity endpoint (e.g., EC50). A PAF of 20% means that 20% of the species in the SSD are expected to be affected at that concentration. This provides a quantitative index of the magnitude of the risk to biodiversity [4] [3].

Current Research and Applications in ERA

Validation and Protectiveness of Laboratory-Based SSDs

A key question in SSD research is whether thresholds derived from laboratory single-species tests are protective of effects in more complex, real-world ecosystems. Multiple studies have compared laboratory-based SSDs with results from multi-species semi-field experiments (e.g., mesocosms) [5] [1] [2]. The consensus from these analyses is that, for the majority of pesticides, the output from a laboratory SSD (such as the HC1 or lower-limit HC5) was protective of effects observed in semifield communities [5] [2]. This supports the use of SSDs as a higher-tier assessment tool in regulatory ecotoxicology.

Addressing Taxonomic and Mode-of-Action Differences

Research has demonstrated that the sensitivity profile of species to a chemical is strongly influenced by its Mode of Action (MoA). Extensive analyses of pesticides have shown that separate SSDs for different taxonomic groups are often required for herbicides and insecticides [5]. For instance, herbicides are typically most toxic to primary producers (algae, plants), while insecticides are most toxic to arthropods [5] [4]. Understanding the MoA is therefore critical for constructing a representative SSD, as it ensures that the most sensitive taxonomic group is adequately included in the distribution [5] [4].

Table 1: Example HC5 Values for Pesticides with Different Modes of Action (MoA)

| Pesticide | Type | MoA | Sensitive Group | HC5 (µg/L) | Registration Criteria (µg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malathion | Insecticide | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Arthropods | 0.23 | 0.3 |

| Trifluralin | Herbicide | Microtubule assembly inhibitor | Primary Producers | 5.1 | 24 |

| 2,4-D | Herbicide | Synthetic auxin | Primary Producers | 330 | 9800 |

| Methomyl | Insecticide | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Arthropods | 2.7 | 1.5 |

Source: Adapted from [4]. Note: HC5 values are based on acute toxicity data.

Advancements in Ecosystem-Level Risk Assessment

A significant advancement in SSD research is the move towards ecosystem-level risk assessment. One innovative approach integrates the SSD model with thermodynamic theory, introducing exergy and biomass indicators of communities from various trophic levels [6]. In this method, species are classified into trophic levels (e.g., algae, invertebrates, vertebrates), and each level is weighted based on its relative biomass and contribution to the ecosystem function. This allows for the establishment of a system-level ERA protocol (ExSSD) that provides a more holistic risk estimate by accounting for the structure and function of the entire ecosystem, moving beyond the protection of individual species [6].

Application to Non-Toxic Stressors

While originally developed for toxic chemicals, the SSD approach has been adapted to assess the risk of non-toxic stressors, such as suspended clay particles, sedimentation, and other physical disturbances [3]. This expansion allows for a unified framework to assess the impact of multiple stressors. However, for non-toxic stressors, laboratory test protocols are often less standardized than for toxicants, which can introduce greater uncertainty into the risk calculations [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Constructing a Standard SSD

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a Species Sensitivity Distribution for a chemical, based on established practices in the literature [5] [4] [3].

1. Problem Formulation and Objective Definition

- Define the protection goal (e.g., protection of aquatic life, soil organisms).

- Define the spatial scope (e.g., regional, national, global assessment).

2. Data Collection and Compilation

- Source Data: Collect ecotoxicity data from peer-reviewed literature, regulatory databases, and high-quality grey literature.

- Endpoint Selection: Use consistent and relevant toxicity endpoints. For acute SSDs, the EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) or LC50 (median lethal concentration) are commonly used. For chronic SSDs, the NOEC (No Observed Effect Concentration) is often employed [3].

- Data Requirements: Aim for a minimum of 8-10 species from at least 5-8 different taxonomic groups to ensure statistical robustness and ecological relevance [3].

3. Data Screening and Selection

- Quality Control: Include only data from tests following standard guidelines (e.g., OECD, EPA) or studies where the methodology is clearly documented and deemed reliable.

- Taxonomic Diversity: Ensure the dataset covers a range of taxonomic groups relevant to the assessment. For an aquatic SSD, this typically includes fish, crustaceans (e.g., Daphnia), insects, mollusks, and algae/plants [5] [4].

- Geographical and Habitat Considerations: Research indicates that toxicity data for species from different geographical areas and habitats (e.g., fresh water, sea water) can be combined, provided the SSD accounts for differences in the most sensitive taxonomic group(s) [5].

4. SSD Construction and Statistical Analysis

- Data Transformation: Log-transform the toxicity data (e.g., log10(EC50)) to normalize the distribution.

- Distribution Fitting: Fit a statistical distribution to the ranked, log-transformed data. The log-normal distribution is frequently used, but other distributions (e.g., log-logistic, Burr Type III) can be applied.

- Goodness-of-Fit: Use statistical tests (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Anderson-Darling) or graphical checks to assess the fit of the chosen distribution.

5. Derivation of Hazard Concentrations (HCs)

- Calculate HC5: Use the fitted distribution to calculate the HC5 and its associated confidence interval (e.g., 90% or 95% CI). The HC5 is the concentration corresponding to the 5th percentile of the fitted cumulative distribution.

- Other Percentiles: The HC1 or HC10 may also be calculated for more conservative or less conservative protection goals, respectively.

6. Risk Characterization

- For Standard Derivation: The HC5 (or a value derived from it, such as HC5/3) is often proposed as the PNEC [5].

- For Probabilistic Assessment: Calculate the Potentially Affected Fraction (PAF) of species for a given exposure concentration (PEC) [3].

Protocol for Ecosystem-Level ERA Using ExSSD

This protocol describes the advanced method for system-level risk assessment that incorporates ecosystem structure [6].

1. Trophic Level Classification

- Classify all species in the toxicity dataset into predefined trophic levels (TLs):

- TL1: Primary producers (e.g., algae, aquatic plants)

- TL2: Invertebrates (e.g., Daphnia, insects)

- TL3: Vertebrates (fish)

2. Community-Level SSD Development

- Construct separate SSDs for each trophic level (TL1, TL2, TL3) using the standard protocol.

3. Weighting Factor Determination

- Determine the weight (W_i) for each trophic level based on its relative biomass in the target ecosystem and a β-value, which indicates the holistic contribution of each species or community to the ecosystem. The β-value is often derived from thermodynamic exergy considerations.

4. System-Level Risk Curve (ExSSD) Integration

- Integrate the community-level SSDs using the weighting factors to generate a single system-level ERA curve (ExSSD).

- The ExSSD provides a risk estimate that reflects the structure and functional importance of different components of the ecosystem.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for SSD-Related Research

| Item/Category | Function and Description in SSD Context |

|---|---|

| Standard Test Organisms | Representative species from key taxonomic groups used to generate core toxicity data. Examples include the algae Raphidocelis subcapitata, the crustacean Daphnia magna, and fish such as Cyprinus carpio (carp) or Oncorhynchus mykiss (rainbow trout) [4]. |

| Toxicant Standards | High-purity analytical-grade chemicals for which toxicity tests are conducted. The Mode of Action (MoA) of the toxicant must be known to guide species selection for the SSD [5] [4]. |

| Culture Media & Reagents | Standardized media (e.g., OECD, EPA reconstituted water) and high-quality water for culturing test organisms and conducting toxicity tests to ensure reproducibility and data reliability. |

| Statistical Software Packages | Software capable of statistical distribution fitting and percentile calculation (e.g., R with appropriate packages, SSD Master, ETX 2.0) is essential for constructing the SSD and deriving HC values. |

| Ecotoxicity Databases | Curated databases (e.g., US EPA ECOTOX, eChemPortal) that provide compiled, quality-checked ecotoxicity data for a wide range of chemicals and species, forming the foundation for data compilation [4]. |

| Allo-hydroxycitric acid lactone | Allo-hydroxycitric acid lactone, CAS:469-72-7, MF:C6H6O7, MW:190.11 g/mol |

| Isorhapontin | Isorhapontin, MF:C21H24O9, MW:420.4 g/mol |

Critical Considerations and Future Directions

Despite its widespread application, the SSD approach has limitations that are active areas of research. A significant limitation is that toxicity datasets used to derive SSDs often lack information on all taxonomic groups, and data for heterotrophic microorganisms, which play key roles in ecosystem functions like decomposition, are generally absent [5]. Initial limited information suggests that microbially-mediated functions may be protected by thresholds based on non-microbial data, but this requires more investigation [5].

Future directions for SSD development include:

- Integrating 'Omics Data: Employing toxicogenomics to enrich toxicity databases and understand the mechanistic bases of sensitivity [6].

- Modeling Ecological Interactions: Using ecological dynamic models to simulate species interactions (e.g., predation, competition) that are absent in standard laboratory tests [6].

- Incorporating Environmental Fate: Introducing chemical fate and bioaccumulation models into system-level ERA to account for exposure dynamics [6].

- Refining Ecosystem Weighting: Further development of methods, like the ExSSD, to better account for ecosystem structure and function in risk estimates [6].

The SSD remains a practical, useful, and validated tool for environmental risk assessment. Its ability to integrate information from all tested species and to quantify risk as the Potentially Affected Fraction (PAF) makes it a powerful component of the ecological risk assessor's toolkit, especially for informing the protection and management of ecosystems under multiple stressors [3].

Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) are statistical models that aggregate toxicity data across multiple species to quantify the distribution of their sensitivities to an environmental contaminant [7]. By fitting a cumulative distribution function to available toxicity data, SSDs enable the estimation of a Hazard Concentration (HCx)—the concentration at which a specified percentage (x%) of species is expected to be affected [8]. The HC5, the concentration affecting 5% of species, is a commonly used benchmark in ecological risk assessment [7] [8]. This approach addresses the vast combinatorial space of chemical-species interactions, providing a robust computational framework for ecological protection where traditional empirical methods fall short [7]. SSDs are considered a probabilistic approach that accounts for species variability and uncertainty in sensitivity towards chemicals, offering a more refined tool for defining Environmental Quality Criteria compared to deterministic methods [9].

Core Statistical Methodology

The foundational principle of SSD modeling is that the sensitivities of different species to a particular stressor follow a probability distribution. The process involves collecting measured toxicity endpoints (e.g., EC50, LC50, NOEC) for a set of species, fitting a statistical distribution to these data, and deriving the HCx value from the fitted model.

The general workflow can be described by the following logical relationship, which outlines the key stages from data collection to risk assessment application:

Data Requirements and Curation

The construction of a reliable SSD requires a curated dataset of toxicity entries spanning multiple taxonomic groups. A robust dataset should encompass species across different trophic levels, including producers (e.g., algae), primary consumers (e.g., insects), secondary consumers (e.g., amphibians), and decomposers (e.g., fungi) [7].

Data Quality Assessment: To ensure the derivation of robust and reliable Hazard Concentrations, a systematic assessment of ecotoxicological data quality is essential. Modern frameworks employ Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) and Weight of Evidence (WoE) approaches to quantitatively score the reliability and relevance of each data point [9]. This process evaluates factors such as test methodology standardization, endpoint relevance, and statistical power, allowing for the production of data-quality weighted SSDs (SSD-WDQ) that provide more accurate hazard estimates [9].

Table: Types of Ecotoxicity Endpoints Used in SSD Development

| Endpoint Type | Description | Commonly Used Endpoints | Application in SSDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | Short-term effects, usually from tests of short duration (e.g., 24-96 hours) | EC50, LC50, IC50 [10] | Often require extrapolation to chronic equivalents for protective assessments [10] |

| Chronic | Long-term effects, from tests spanning a significant portion of an organism's life cycle | NOEC, LOEC, EC10, EC20 [10] | Preferred for deriving HCx values as they represent more subtle, population-relevant effects [10] [9] |

Statistical Distribution Fitting and HCx Estimation

The core of SSD modeling involves fitting a statistical distribution to the compiled and curated toxicity data. The fitted distribution represents the cumulative probability of a species being affected at a given concentration.

The Hazard Concentration for a protection level of (p\%) (where (p) is typically 5) is calculated as the ((p/100))th percentile of the fitted distribution. Formally: [ HCp = F^{-1}(p/100) ] where (F^{-1}) is the quantile function of the fitted distribution [7] [8].

The most common distributions used in SSD modeling include the log-normal, log-logistic, and Burr Type III distributions. The choice of distribution can impact the HCx estimate, and model averaging or selection based on goodness-of-fit criteria is often employed.

Quantitative Data and Extrapolation Factors

The derivation of HCx values relies on a quantitative foundation of toxicity data. Research has established specific extrapolation factors to bridge data gaps, particularly for converting acute toxicity data to chronic equivalents.

Table: Acute to Chronic Extrapolation Ratios for Major Taxonomic Groups

| Taxonomic Group | Acute EC50 to Chronic NOEC Ratio (Geometric Mean) | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Fish | 10.64 | Analysis of REACH database data [10] |

| Crustaceans | 10.90 | Analysis of REACH database data [10] |

| Algae | 4.21 | Analysis of REACH database data [10] |

These ratios support the calculation of chronic NOEC equivalents (NOECeq) from acute EC50 data, which is crucial given the more limited availability of chronic data [10]. Studies comparing hazard values derived from different data types have found that using chronic NOECeq data shows the best agreement with official chemical classifications like the EU's Classification, Labelling and Packaging (CLP) regulation, outperforming methods that rely solely on acute data or mixed acute-chronic data with simplistic extrapolation factors [10].

Experimental Protocols for SSD Development

Protocol: Constructing a Species Sensitivity Distribution

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for constructing an SSD, from data collection to HCx estimation, drawing on established practices from recent research [7] [9] [11].

1. Define Scope and Select Chemicals

- Clearly define the assessment goal (e.g., deriving a water quality criterion for a specific chemical, prioritizing chemicals for regulation).

- Identify the chemical or chemical class for assessment. High-priority classes often include personal care products (PCPs) and agrochemicals [7].

2. Data Collection and Compilation

- Source data from curated ecotoxicity databases such as the U.S. EPA ECOTOX database [7] [8] or the REACH database [10].

- Collate all available acute (EC50, LC50) and chronic (NOEC, LOEC, EC10, EC20) endpoints [7] [10].

- Aim for a dataset that spans a wide taxonomic breadth, covering at least 8-10 species from different trophic levels (e.g., algae, crustaceans, insects, fish, amphibians) [7].

3. Data Curation and Weighting

- Apply a quality assessment framework to each data point. The MCDA-WoE methodology can be used to score the reliability and relevance of each datum [9].

- Assign weighting coefficients based on the quality scores. This step is critical for producing SSD-WDQ (SSD weighted by data quality) graphs that provide more reliable hazard estimates [9].

- For data-poor scenarios, apply validated acute-to-chronic ratios (see Table 2) to generate chronic NOECeq values [10].

4. Data Pooling and Transformation

- Pool equivalent endpoints (e.g., NOEC, LOEC, EC10 into a chronic NOECeq category) [10].

- Perform a logarithmic transformation (usually base 10) of all concentration values to normalize the data and stabilize variance.

5. Statistical Distribution Fitting

- Fit one or more statistical distributions (e.g., log-normal, log-logistic) to the transformed data using maximum likelihood estimation or regression techniques.

- Assess the goodness-of-fit using statistical measures like the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

6. HCx Estimation and Uncertainty Analysis

- Calculate the HCx (e.g., HC5, HC50) from the fitted distribution as the ((x/100))th percentile [7] [11].

- Derive confidence intervals around the HCx estimate using appropriate methods such as bootstrapping to quantify uncertainty [11].

7. Model Validation and Application

- Validate the model by comparing its predictions with known toxicity classifications or PNEC (Predicted No-Effect Concentration) values from regulatory databases [10].

- Apply the model for its intended purpose, such as prioritizing high-toxicity compounds for regulatory attention [7] [8] or conducting probabilistic ecological risk assessment [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key procedural stages and decision points in this protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Resources for SSD Development Research

| Tool / Resource | Function in SSD Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Ecotoxicological Databases | Provide raw toxicity data for multiple species and chemicals; the foundation for building SSDs. | U.S. EPA ECOTOX database [7] [8], REACH database [10] |

| Data Quality Assessment Framework | Systematically evaluates the reliability and relevance of individual ecotoxicity studies for inclusion in SSDs. | MCDA-WoE (Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis-Weight of Evidence) methodology [9] |

| Statistical Software/Platforms | Perform distribution fitting, calculate HCx values, and conduct uncertainty analysis. | R Statistical Environment, OpenTox SSDM platform [7] [8] |

| Acute-to-Chronic Extrapolation Factors | Convert more readily available acute toxicity data into chronic equivalents for protective assessments. | Taxon-specific factors (e.g., 10.9 for crustaceans, 10.6 for fish) [10] |

| Weighting Coefficients | Assign influence to data points in SSD construction based on quality, taxonomic representativeness, and intraspecies variation. | Combined reliability and relevance scores [9] |

| 3'-O-Decarbamoylirumamycin | 3'-O-Decarbamoylirumamycin, MF:C40H64O11, MW:720.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Medorinone | Medorinone, CAS:88296-61-1, MF:C9H8N2O, MW:160.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) are statistical models fundamental to modern ecological risk assessment and chemical regulation. They quantify the variation in sensitivity of different species to a chemical stressor, enabling the derivation of protective environmental benchmarks [12]. By fitting a statistical distribution to single-species ecotoxicity data, regulators can determine a Hazardous Concentration (HCp) expected to protect a specific proportion (p%) of species in an ecosystem [13] [12]. The most common benchmark, the HC5, is the concentration at which 5% of species are expected to be adversely affected [12]. The SSD approach provides a transparent, statistically rigorous method for establishing environmental quality standards such as Predicted-No-Effect Concentrations (PNECs) under regulations like the European Water Framework Directive [13]. Its application has been adopted by numerous countries including the Netherlands, Denmark, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand for developing environmental quality benchmarks [12].

Key Principles and Regulatory Applications

The fundamental principle of an SSD is that interspecies differences in sensitivity to a given chemical resemble a bell-shaped distribution when plotted on a logarithmic scale [13]. This model acknowledges that within a biological community, species exhibit a range of responses to toxicants, and protection should extend beyond a few tested laboratory species to the broader ecosystem.

The construction and application of an SSD model in a regulatory context can be summarized in a logical workflow, progressing from data collection to regulatory decision-making.

SSDs support two primary types of regulatory applications [13]:

- Chemical Safety Assessment & Environmental Quality Standards: Using chronic no-observed-effect concentrations (NOECs) or related endpoints to derive protective benchmarks (e.g., PNEC) below which ecosystems are considered "sufficiently protected."

- Impact Quantification in Comparative Assessments: Using acute median effective concentrations (EC50) to quantify likely impacts of chemical pollution, expressed as expected proportion of species affected or lost, commonly applied in Life Cycle Assessment.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Collection and Curation

The foundation of a reliable SSD is a high-quality, curated ecotoxicity dataset. A comprehensive protocol involves gathering data from multiple sources and applying rigorous quality control measures.

Primary Data Sources:

- Validated ecotoxicity databases: Include well-referenced aquatic ecotoxicity databases containing chronic NOEC and acute EC50 values [13].

- Public databases: EPA ECOTOX database, ECETOC EAT data, and other publicly available sources provide extensive species-chemical toxicity records [12].

- Regulatory databases: REACH registry data, though requiring careful evaluation of test conditions and traceability [13].

- Supplemental sources: Peer-reviewed literature, regulatory agency reports (e.g., European Food Safety Authority, Swiss Centre for Applied Ecotoxicology), and specialized databases for specific chemical classes (e.g., pesticides, pharmaceuticals) [13].

Data Curation Protocol:

- Endpoint Classification: Designate records as "chronic NOEC" or "acute EC50" based on test duration and effect criteria [13].

- Plausibility Checking: Compare toxicity estimates against known ranges and trace implausible outcomes to original references to identify unit transformation errors, typing errors, or suboptimal test conditions [13].

- Error Correction: Correct erroneous entries when possible; remove data when original sources cannot be verified [13].

- Taxonomic Harmonization: Standardize species nomenclature across datasets to ensure consistent grouping.

Species Selection and Data Preprocessing

Appropriate species selection is critical for constructing a representative SSD. The following protocol ensures ecological relevance and statistical robustness:

Species Selection Criteria:

- Include a minimum of 8-10 species from at least 4-6 different taxonomic groups [12].

- Represent multiple trophic levels (algae, crustaceans, fish, insects, mollusks) [12].

- Prioritize locally relevant or ecologically important species when assessment is region-specific [12].

- Ensure inclusion of species known to be sensitive to the chemical class of interest.

Data Preprocessing Steps:

- Acute-to-Chronic Transformation: For chemicals lacking chronic data, apply established conversion methods:

- Use Acute-to-Chronic Ratios (ACR) based on chemical-specific data when available [12].

- Apply the ACT (Acute-Chronic Transformation) method which distinguishes between vertebrates and invertebrates and uses binary regression relationships [12].

- Utilize generalized relationships from large datasets (e.g., De Zwart 2002 analysis of mean and standard deviation relationships) [12].

- Endpoint Standardization: Normalize diverse endpoints (LC50, EC50, NOEC, MATC) to consistent metrics for SSD construction.

- Data Quality Filtering: Apply quality scoring systems (e.g., Klimisch criteria) to prioritize reliable data [13].

SSD Curve Fitting and HC5 Derivation

The core statistical protocol for SSD development involves distribution fitting and benchmark derivation:

Distribution Fitting Protocol:

- Log-Transformation: Log-transform all ecotoxicity values (typically base 10) to approximate a normal distribution [13] [12].

- Distribution Selection: Fit an appropriate statistical distribution to the transformed data. Common choices include:

- Goodness-of-Fit Evaluation: Assess distribution fit using statistical tests (Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Anderson-Darling) and graphical methods (QQ-plots) [14].

- HC5 Calculation: Derive the Hazardous Concentration for 5% of species (HC5) from the fitted distribution, representing the concentration expected to protect 95% of species [12].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Calculate confidence intervals around the HC5 using methods such as:

Assessment Factor Application: Apply appropriate assessment factors to the HC5 based on data quality and species representation:

- High-quality data with many species: Assessment factor of 1-5

- Limited data or poor taxonomic diversity: Assessment factor of 5-10 or higher

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 1: Ecotoxicity Data Requirements for SSD Construction

| Data Characteristic | Chronic SSD | Acute SSD | Regulatory Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Endpoints | NOEC, LOEC, EC10, MATC | LC50, EC50 (mortality/immobility) | Endpoint determines protection goals |

| Minimum Test Duration | Taxon-dependent: Algae (72h), Daphnids (21d), Fish (28d) | Taxon-dependent: Algae (72h), Daphnids (48h), Fish (96h) | Must ensure biological significance |

| Minimum Number of Species | 8-10 species minimum | 8-10 species minimum | Improves statistical reliability |

| Taxonomic Diversity | 4-6 different taxonomic groups | 4-6 different taxonomic groups | Ensures ecosystem representation |

| Data Quality Requirements | Prefer Klimisch score 1-2; documented test conditions | Prefer Klimisch score 1-2; standardized protocols | Reduces uncertainty in benchmarks |

| ACR Application | Preferred: chemical-specific chronic data | Can be used to estimate chronic values | Default ACRs increase uncertainty |

The U.S. EPA's Species Sensitivity Distribution Toolbox provides a standardized approach for regulatory SSD application [15] [14]. This computational resource enables:

Table 2: SSD Toolbox Components and Functions

| Toolbox Component | Function | Regulatory Application |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution Fitting | Supports normal, logistic, triangular, and Gumbel distributions | Allows comparison of different statistical approaches |

| Goodness-of-Fit Evaluation | Provides methods to assess distribution fit to data | Helps validate model assumptions and appropriateness |

| HCp Calculation | Derives hazardous concentrations with confidence intervals | Quantifies uncertainty in protective benchmarks |

| Data Visualization | Generces SSD curves and comparative plots | Facilitates communication of assessment results |

| Taxonomic Analysis | Incorporates phylogenetic considerations | Identifies potentially vulnerable taxonomic groups |

The Toolbox follows a three-step procedure: (1) compilation of toxicity test results for various species exposed to a chemical, (2) selection and fitting of an appropriate statistical distribution, and (3) inference of a protective concentration based on the fitted distribution [15].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SSD Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Toxicants | Quality control of test organisms; laboratory proficiency assessment | Standardized toxicity tests (e.g., Daphnia magna with potassium dichromate) |

| Culturing Media | Maintenance of test organisms under standardized conditions | Continuous culture of algae, invertebrates, and other test species |

| Analytical Grade Chemicals | Chemical stock solution preparation for definitive toxicity tests | Ensuring precise exposure concentrations in laboratory studies |

| Water Quality Kits | Monitoring of test conditions (pH, hardness, ammonia, dissolved oxygen) | Verification of acceptable test conditions per standardized protocols |

| Species-Specific Test Kits | Specialized materials for culturing and testing specific taxa | Maintenance of sensitive or legally required test species |

| Oryzoxymycin | Oryzoxymycin, CAS:12640-81-2, MF:C10H13NO5, MW:227.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Centaurein | Centaurein, CAS:35595-03-0, MF:C24H26O13, MW:522.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Mixture Risk Assessment

SSD methodology has been extended to address complex chemical mixtures in environmental samples through the concept of the multi-substance Potentially Affected Fraction (msPAF) [13] [12]. This approach quantifies the combined toxic pressure of multiple contaminants, accounting for their possible additive or interactive effects. The methodology involves calculating the PAF for each individual chemical and then combining these using principles of concentration addition or response addition, depending on the assumed mode of action [12].

The utility of this approach was demonstrated in a large-scale case study assessing chronic and acute mixture toxic pressure of 1,760 chemicals across over 22,000 European water bodies [13]. The results provided a quantitative likelihood of mixture exposures exceeding negligible effect levels and increasing species loss, supporting management prioritization under the European Water Framework Directive [13].

Emerging Innovations and Methodological Refinements

Future developments in SSD methodology focus on addressing current limitations and enhancing predictive capability:

- Incorporation of Phylogenetic Information: Emerging consensus suggests that including evolutionary relationships can help identify taxa at greatest risk and improve predictions for data-poor species [14].

- Enhanced Statistical Modeling: Next-generation SSDs aim to incorporate both random and systematic variation among taxa in sensitivity, moving beyond the assumption that all variation is random [14].

- Trait-Based Approaches: Integrating physiological, ecological, and life-history traits to explain and predict sensitivity patterns across taxonomic groups [14].

- Uncertainty Analysis Advancement: Improved methods for quantifying and propagating uncertainty through the entire assessment chain, from initial toxicity data to final risk management decisions [12].

These innovations will strengthen the scientific foundation of SSDs and enhance their utility in regulatory contexts, particularly for addressing the ecological risks posed by the thousands of chemicals with limited toxicity data [13] [14].

Linking SSDs to Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs) for Mechanistic Insight

The ecological risk assessment of chemicals has traditionally relied on Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs), a statistical approach that models the variation in sensitivity to a toxicant across a community of species. The Hazardous Concentration for 5% of species (HC5) is a critical benchmark derived from SSDs, used to set protective environmental quality guidelines [16]. However, a primary limitation of conventional SSDs is their black-box nature; they describe the "what" but not the "why" of differential species sensitivity. The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework offers a solution to this limitation by providing a structured, mechanistic description of the sequence of events from a molecular initiating event to an adverse outcome at the organism or population level [17].

Linking these two frameworks creates a powerful paradigm for modern ecotoxicology. Integrating the mechanistic insight of AOPs with the probabilistic risk assessment power of SSDs allows researchers to move beyond descriptive models and develop predictive, hypothesis-driven tools for environmental protection. This integration is particularly valuable for addressing complex contaminants like Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs), where traditional endpoints may not capture the full spectrum of biological effects [18]. Furthermore, this linkage helps address a fundamental theoretical assumption (T1) in SSD models: that ecological interactions do not influence the sensitivity distribution, an assumption that has been shown to be frequently invalid [19]. By providing a biological basis for observed sensitivity rankings, the AOP-SSD framework enhances the scientific defensibility and regulatory acceptance of ecological risk assessments.

Theoretical Foundation and Key Concepts

Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs)

An SSD is a statistical distribution that describes the variation in toxicity of a specific chemical or stressor across a range of species. The distribution is typically fitted using single-species toxicity data (e.g., LC50 or EC50 values), from which the Hazardous Concentration for 5% of species (HC5) is extrapolated [16]. This HC5 value represents the concentration at which 5% of species in an ecosystem are expected to be adversely affected. For regulatory purposes, the HC5 is often divided by an Assessment Factor (AF) to derive a Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC), which is used as a benchmark for safe environmental levels [16]. The underlying data for constructing SSDs can be sourced from acute or chronic toxicity tests, and the choice significantly impacts the derived safety thresholds.

The mode of action (MoA) of a chemical is a key determinant of the shape and range of its SSD. Research has demonstrated that the specificity of the MoA influences the variability in species sensitivity. The distance from baseline (narcotic) toxicity can be quantified using a Toxicity Ratio (TR):

TR = HC5(baseline) / HC5(experimental)

where the baseline HC5 is predicted from a QSAR model for narcotic chemicals [16]. A larger TR indicates a more specific, and typically more potent, mode of action. For example, insecticides, which often have specific neuronal targets, exhibit much higher toxicity (median HC5 = 1.4 × 10â»Â³ µmol Lâ»Â¹) to aquatic communities than herbicides (median HC5 = 3.3 × 10â»Â² µmol Lâ»Â¹) or fungicides (median HC5 = 7.8 µmol Lâ»Â¹) [16]. This underscores that chemical class and MoA must be considered when developing and interpreting SSDs.

Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs)

An AOP is a conceptual framework that organizes existing knowledge about toxicological mechanisms into a structured sequence of causally linked events. These events begin with a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE), which is the initial interaction of a chemical with a biological macromolecule, and culminate in an Adverse Outcome (AO) relevant to risk assessment and regulatory decision-making [17]. The pathway is composed of intermediate, measurable Key Events (KEs) and the Key Event Relationships (KERs) that describe the causal linkages between them.

The essential components of an AOP, as defined by the OECD Handbook, are detailed in the table below [17].

Table 1: Core Components of an Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP)

| Component | Acronym | Definition | Role in the AOP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Initiating Event | MIE | The initial interaction between a stressor and a biomolecule within an organism. | Starts the pathway; defines the point of perturbation. |

| Key Event | KE | A measurable change in biological state that is essential for the progression of the AOP. | Represents a critical checkpoint along the pathway to adversity. |

| Key Event Relationship | KER | A scientifically-based description of the causal relationship linking an upstream and downstream KE. | Enables prediction of downstream effects from measurements of upstream events. |

| Adverse Outcome | AO | An effect at the organism or population level that is of regulatory concern. | The final, harmful outcome the AOP seeks to explain and predict. |

AOPs are intended to be modular; a single KE (e.g., inhibition of a specific enzyme) can be part of multiple AOPs leading to different AOs. This modularity promotes the efficient assembly of AOP networks from existing building blocks within knowledgebases like the AOP-Wiki [17].

Integrated AOP-SSD Framework: Protocol for Development and Application

The integration of AOPs and SSDs involves a systematic process to connect mechanistic biological pathways to population-level ecological consequences. The following protocol outlines the key stages, from AOP development to the construction and interpretation of a mechanistically informed SSD.

Protocol 1: Development of an Integrated AOP-SSD

Objective: To create a Species Sensitivity Distribution that is informed by the Key Events of an Adverse Outcome Pathway, thereby providing a mechanistic explanation for observed interspecies sensitivity.

Materials and Reagents:

- AOP-Wiki Database: The primary knowledgebase for existing AOPs, KEs, and KERs.

- Toxicity Databases: Repositories of single-species toxicity data (e.g., ECOTOX from the US EPA).

- Statistical Software: Capable of probabilistic distribution fitting (e.g., R with appropriate packages).

- Computational Modeling Environment: Software for dynamic systems modeling (optional, for advanced ecosystem simulations).

Procedure:

AOP Identification and Development:

- Identify the Adverse Outcome (AO): Define the ecologically relevant endpoint of concern (e.g., population decline, reproductive impairment).

- Assemble the AOP: Using the AOP-Wiki and literature review, map the causal pathway from a plausible MIE to the AO. Critically evaluate the Weight of Evidence (WoE) for each KER based on biological plausibility, essentiality of KEs, and empirical consistency [17]. The workflow for this stage is outlined in Figure 1 below.

Toxicity Data Curation and Key Event Mapping:

- Gather Species-Specific Toxicity Data: Collect high-quality, peer-reviewed toxicity data (LC50, EC50, NOEC) for the chemical(s) of interest, focusing on the AO or a relevant KE.

- Map Species Sensitivities to KEs: For each species in the dataset, investigate and document its specific response at the level of the MIE and intermediate KEs. This may involve literature review or targeted assays. The sensitivity of a species is hypothesized to be determined by the "weakest link" or slowest rate-determining step in its AOP.

SSD Construction and Mechanistic Interpretation:

- Construct a Conventional SSD (cSSD): Fit a statistical distribution (e.g., log-normal, log-logistic) to the compiled toxicity data for the AO. Calculate the HC5 and other relevant statistics [16].

- Stratify the SSD Using AOP Knowledge: Group species in the SSD based on their known or predicted susceptibility at a critical KE. For instance, species known to possess a highly sensitive molecular target (the MIE) should cluster on the more sensitive tail of the distribution. This stratification provides a mechanistic explanation for the statistical distribution of sensitivities.

Validation and Ecosystem Modeling (Advanced):

- Test Against an Eco-SSD: As explored by De Laender et al. [19], use a mechanistic dynamic ecosystem model that incorporates ecological interactions (e.g., predation, competition) to simulate population-level NOECs. Construct an "Eco-SSD" from these model outputs and compare its parameters (mean, variance) to the cSSD. A significant difference challenges the T1 assumption and highlights the role of ecology in modulating toxicological effects.

Figure 1: Workflow for developing an integrated AOP-SSD model, illustrating the parallel development of the AOP and the SSD, and their final integration.

Case Study: Triclosan as a Model Endocrine Disrupting Chemical

Triclosan (TCS), an antimicrobial agent, serves as an illustrative example for applying the AOP-SSD framework to an Endocrine Disrupting Chemical (EDC). A symposium review highlighted that emerging SSD methods are being adopted for EDCs and that the development of an AOP for TCS from an "aquatic organism point of view" can facilitate toxicity endpoint screening and the derivation of more robust PNECs for seawater and sediment environments [18].

Application Notes for TCS:

- AOP Development: The first step is to construct a TCS-specific AOP. While the specific details are under development, a plausible AOP for aquatic organisms might start with the MIE: Inhibition of fatty acid synthesis via enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase, a known target of TCS in bacteria that has homologs in fish and algae.

- Intermediate Key Events: This MIE could lead to a series of KEs, including Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress, which are documented effects of TCS. These cellular-level KEs could then link to organ-level outcomes like Liver Histopathology and Reproductive Dysfunction, ultimately culminating in the AO: Population-Level Decline.

- Linking to SSD: When constructing an SSD for TCS, the toxicity data for the AO (population decline) would be the primary input. The integrated AOP-SSD approach would then investigate whether species with a higher inherent susceptibility to the MIE (e.g., those with a TCS-sensitive version of the target enzyme) or those with a reduced capacity to compensate for oxidative stress are the ones that appear on the sensitive tail of the SSD. This moves the assessment from simply observing that some species are more sensitive to understanding the mechanistic basis for that sensitivity.

Table 2: Quantitative HC5 Values for Pesticide Classes, Demonstrating Differential Potency and Implied MoA Specificity [16]

| Pesticide Class | Median HC5 (µmol Lâ»Â¹) | Relative Toxicity | Implied Mode of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insecticides | 1.4 × 10â»Â³ | Highest (Baseline) | Specific (e.g., neurotoxicity) |

| Herbicides | 3.3 × 10â»Â² | Intermediate | Less Specific |

| Fungicides | 7.8 | Lowest | Reactive / Narcotic |

This quantitative data underscores why the AOP-SSD framework is particularly critical for insecticides and other specifically-acting chemicals, as their high toxicity ratios (TR) indicate a significant deviation from non-specific baseline toxicity [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials, databases, and software tools required for research in AOP-SSD integration.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for AOP and SSD Integration

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOP-Wiki | Knowledgebase | Central repository for developed AOPs, KEs, and KERs; essential for AOP discovery and development. | aopwiki.org [17] |

| ECOTOX Database | Data Repository | Source of curated single-species toxicity data for SSD construction. | US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) |

| log P (Kow) Calculator | QSAR Tool | Predicts baseline narcotic toxicity and chemical partitioning, key for calculating Toxicity Ratios (TR). | Various software (e.g., EPI Suite) [16] |

| Dynamic Ecosystem Model | Computational Tool | Simulates ecological interactions to test the influence of ecology on SSDs (Eco-SSD). | Custom models as in De Laender et al. [19] |

| SSD Fitting Software | Statistical Tool | Fits statistical distributions to toxicity data and calculates HCx values. | R packages (e.g., fitdistrplus, ssdtools) |

| Adverse Outcome Pathway | Conceptual Framework | Provides a structured, mechanistic description of toxicological effects from molecular initiation to adverse outcome. | OECD AOP Developers' Handbook [17] |

| 6-Deoxyisojacareubin | 6-Deoxyisojacareubin|RUO | Bench Chemicals | |

| 4-Hydroxyderricin | 4-Hydroxyderricin, CAS:55912-03-3, MF:C21H22O4, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of Species Sensitivity Distributions with Adverse Outcome Pathways represents a paradigm shift in ecotoxicology, moving the field from a descriptive to a predictive and mechanistic science. This linkage provides a biological basis for the differential sensitivities observed across species, thereby increasing the scientific confidence in derived environmental safety thresholds like the PNEC. The application of this framework is especially critical for addressing the challenges posed by contaminants of emerging concern, such as Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals, where traditional testing paradigms may be insufficient.

Future research should focus on the quantitative elaboration of KERs to allow for predictive modeling of AOP progression, which can be directly incorporated into probabilistic risk assessment. Furthermore, expanding the use of ecosystem models to validate AOP-informed SSDs against real-world ecological outcomes will be essential for bridging the gap between laboratory data and field-level protection. By adopting the protocols and applications outlined in this document, researchers and regulators can work towards a more transparent, mechanistic, and ultimately more effective system for ecological risk assessment.

The discovery and development of novel pharmaceuticals requires a deep understanding of how therapeutic compounds interact with their biological targets. Evolutionary conservation—the preservation of genes and proteins across species—provides a critical framework for extrapolating pharmacological findings from model organisms to humans. Simultaneously, this conservation pattern directly influences species sensitivity to chemical compounds, including pharmaceuticals that enter the environment. This application note explores how the principle of evolutionary conservation bridges human pharmacology and environmental toxicology, specifically through the development and application of Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs). We provide detailed protocols for quantifying conservation patterns and integrating them into ecological risk assessment frameworks, enabling more predictive toxicology for drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundation: Evolutionary Conservation of Drug Targets

Quantitative Conservation Patterns Across Species

Drug target genes exhibit significantly higher evolutionary conservation compared to non-target genes, as demonstrated by comprehensive genomic analyses. This conservation manifests through multiple measurable parameters:

Table 1: Evolutionary Conservation Metrics for Human Drug Targets [20]

| Conservation Metric | Drug Target Genes | Non-Target Genes | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary rate (dN/dS) | Significantly lower | Higher | P = 6.41E-05 |

| Conservation score | Significantly higher | Lower | P = 6.40E-05 |

| Percentage with orthologs | Higher | Lower | P < 0.001 |

| Network connectivity | Tighter network structure | More dispersed | P < 0.001 |

These evolutionary patterns have direct implications for environmental risk assessments of pharmaceuticals. Research has demonstrated that 86% of human drug targets have orthologs in zebrafish, compared to only 61% in Daphnia and 35% in green algae [21]. This differential conservation creates a predictable pattern of species sensitivity where organisms with more conserved targets demonstrate higher susceptibility to pharmaceutical compounds designed for human targets.

Implications for Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs)

The differential conservation of drug targets across species provides a mechanistic basis for understanding variability in chemical sensitivity. SSDs statistically aggregate toxicity data across multiple species to quantify the distribution of sensitivities within ecological communities, enabling estimation of hazardous concentrations (e.g., HCâ‚…, the concentration affecting 5% of species) [7]. The evolutionary conservation perspective explains why SSDs for pharmaceuticals often show particular sensitivity patterns across taxonomic groups, with vertebrates typically being more sensitive to human drugs than invertebrates or plants due to higher target conservation.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Drug Target Conservation Across Species

Purpose: To systematically identify orthologs of human drug targets in ecologically relevant species and quantify conservation metrics.

Materials:

- Reference sequences: Human drug target protein sequences from DrugBank or TTD databases

- Target species proteomes: Protein sequences for species of interest (e.g., zebrafish, Daphnia, algae)

- Software: BLAST+ suite, OrthoFinder, R or Python for statistical analysis

- Computing resources: Workstation with multi-core processor and ≥16GB RAM

Procedure: [20]

Data Acquisition:

- Download canonical protein sequences for all established human drug targets from curated databases

- Obtain complete proteomes for target species from Ensembl, NCBI, or species-specific databases

Ortholog Identification:

- Perform all-versus-all BLASTP search between human drug targets and target species proteomes

- Apply reciprocal best hit criterion to identify high-confidence ortholog pairs

- Filter matches with E-value < 1e-10 and sequence identity >30%

Conservation Quantification:

- Perform multiple sequence alignment using MAFFT or Clustal Omega for each ortholog group

- Calculate evolutionary rates (dN/dS) using PAML or similar packages

- Compute conservation scores using ConSurf or custom scoring matrices

Statistical Analysis:

- Compare conservation metrics between drug targets and non-target genes using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests

- Correlate conservation levels with taxonomic distance from humans

- Generate visualization plots of conservation patterns across the tree of life

Expected Outcomes: This protocol generates quantitative conservation scores for drug targets across species, enabling prediction of which ecological organisms will be most sensitive to specific pharmaceutical classes based on target conservation.

Protocol 2: Incorporating Evolutionary Data into SSD Development

Purpose: To integrate evolutionary conservation metrics into species sensitivity distribution modeling for ecological risk assessment of pharmaceuticals.

Materials:

- Toxicity data: ECâ‚…â‚€/LCâ‚…â‚€ or NOEC/LOEC values from EPA ECOTOX database or literature

- Conservation metrics: Output from Protocol 1

- Modeling software: R with SSD-specific packages (e.g., fitdistrplus, ssdtools)

- Chemical data: Pharmaceutical physicochemical properties from PubChem

Data Curation:

- Collate acute (ECâ‚…â‚€/LCâ‚…â‚€) and chronic (NOEC/LOEC) toxicity data for the pharmaceutical of interest

- Apply quality filters: standardized test durations, relevant endpoints, appropriate controls

- Categorize species by taxonomic group and trophic level

SSD Model Construction:

- Fit log-normal distributions to toxicity data using maximum likelihood estimation

- Calculate HCâ‚… values with 95% confidence intervals

- Assess model fit using goodness-of-fit tests (Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Anderson-Darling)

Integration of Conservation Data:

- Incorporate target conservation scores as weighting factors in SSD models

- Develop separate SSDs for taxonomic groups with different conservation levels

- Validate models by comparing predicted versus observed sensitivity rankings

Application for Risk Assessment:

- Estimate mixture toxic pressure using concentration addition models

- Prioritize pharmaceuticals for regulatory attention based on HCâ‚… values and conservation-weighted sensitivity

- Generate protective concentration thresholds for environmental quality standards

Expected Outcomes: Enhanced SSD models that more accurately predict ecological impacts of pharmaceuticals by incorporating evolutionary conservation of drug targets, leading to more targeted risk assessment and reduced animal testing.

Visualization: Workflow Integration

Figure 1: Integrated workflow diagram illustrating the pipeline from drug target identification to ecological risk assessment using evolutionary conservation principles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Conservation and SSD Studies [7] [21] [20]

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EPA ECOTOX Database | Source of curated ecotoxicity data | Provides standardized toxicity values across species; essential for SSD development |

| DrugBank Database | Repository of drug target information | Contains manually curated information on pharmaceutical targets and mechanisms |

| OrthoFinder Software | Ortholog group inference | Identifies evolutionary orthologs across multiple species with high accuracy |

| BLAST+ Suite | Sequence similarity search | Workhorse tool for identifying homologous sequences in different organisms |

| SSD Modeling Software | Statistical analysis of species sensitivity | Fit distributions, calculate HC values, and generate confidence intervals |

| PAML Package | Phylogenetic analysis | Calculates evolutionary rates (dN/dS) and tests for selection patterns |

| OpenTox SSDM Platform | Web-based SSD modeling | Interactive tool for building and sharing SSD models; promotes collaboration |

| Cryptosporiopsin | Cryptosporiopsin | Cryptosporiopsin is a fungal metabolite for antimicrobial and anticancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| LEXITHROMYCIN | Lexithromycin|Macrolide Antibiotic Research Reagent | Lexithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic for research, inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

The evolutionary conservation of biological targets provides a powerful unifying framework that connects human pharmacology with ecological risk assessment. By quantifying conservation patterns and incorporating them into Species Sensitivity Distribution modeling, researchers can develop more predictive toxicological profiles for pharmaceuticals in the environment. The protocols and resources presented in this application note provide a roadmap for integrating evolutionary principles into the drug development pipeline, enabling more comprehensive safety assessment while potentially reducing animal testing through computational approaches. This integrated perspective supports the development of safer pharmaceuticals and more effective environmental protection strategies.

Developing and Applying SSDs: Methodologies, Tools, and Real-World Use Cases

Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) are a statistical tool widely used in ecological risk assessment to set protective limits for chemical concentrations in surface waters [15]. The core principle involves fitting a statistical distribution to toxicity data collected from a range of different species. This fitted distribution is then used to estimate a concentration that is predicted to be protective of a specified proportion of species in a hypothetical aquatic community, a common benchmark being the HC5 (Hazard Concentration for 5% of species) [15]. This application note provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for developing an SSD and deriving the HC5 value, framed within the context of academic and regulatory research.

Detailed SSD Workflow Protocol

The development of a robust SSD follows a structured, three-step procedure that moves from data collection to computational analysis and finally to derivation of a protective concentration [15]. The workflow is linear and sequential, ensuring each step is completed before moving to the next. The following diagram visualizes this core process.

Step 1: Data Compilation

Objective: To gather and prepare a high-quality dataset of toxicity endpoints for a specific chemical from a diverse set of aquatic species.

Protocol:

- Data Source Identification: Search peer-reviewed literature, regulatory databases (e.g., US EPA ECOTOX Knowledgebase), and reputable gray literature for high-quality, standardized toxicity tests.

- Species Selection: Aim for a minimum of 8-10 species from at least 5 different taxonomic groups (e.g., fish, crustaceans, insects, algae, mollusks) to ensure ecological diversity and statistical robustness.

- Endpoint Compilation: Extract the chosen toxicity endpoint (e.g., LC50, EC50, NOEC) for each species and record it in a consistent unit (e.g., mg/L). It is critical to document the exposure duration and test conditions.

- Data Quality Screening: Apply pre-defined quality criteria to exclude studies with methodological flaws, unclear reporting, or endpoints that are not comparable to the rest of the dataset.

- Data Transformation: Convert all compiled toxicity values to log10-transformed values (e.g., log10(LC50)). This transformation typically normalizes the data, making it more suitable for standard statistical distributions.

Data Output: A table of sorted, log10-transformed toxicity values.

Table: Compiled Toxicity Data for a Hypothetical Chemical 'X'

| Species Name | Taxonomic Group | Endpoint | Exposure Duration (hr) | Toxicity Value (mg/L) | log10(Toxicity Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daphnia magna | Crustacean | EC50 | 48 | 2.5 | 0.3979 |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss | Fish | LC50 | 96 | 8.1 | 0.9085 |

| Pimephales promelas | Fish | LC50 | 96 | 12.3 | 1.0899 |

| Chironomus dilutus | Insect | EC50 | 48 | 1.8 | 0.2553 |

| Selenastrum capricornutum | Algae | EC50 | 96 | 15.0 | 1.1761 |

| Lymnaea stagnalis | Mollusk | LC50 | 48 | 22.5 | 1.3522 |

Step 2: Distribution Fitting

Objective: To select an appropriate statistical distribution and fit it to the compiled log10-transformed toxicity data.

Protocol:

- Distribution Selection: The US EPA SSD Toolbox supports several standard statistical distributions for fitting, including the Normal, Logistic, Triangular, and Gumbel distributions [15]. The choice can be based on statistical fit or regulatory precedent.

- Parameter Estimation: Use the SSD Toolbox to fit the selected distribution to your dataset. The software will computationally derive the distribution's parameters (e.g., the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) for a Normal distribution).

- Goodness-of-Fit Assessment: Evaluate how well the chosen distribution fits the empirical data. The SSD Toolbox provides visualizations and statistical measures for this purpose. A good fit is critical for generating a reliable HC5.

Data Output: A cumulative distribution function (CDF) representing the SSD.

Table: Fitted Parameters for Different Distributions to the Example Dataset

| Distribution Type | Parameter 1 (e.g., μ) | Parameter 2 (e.g., σ) | Goodness-of-Fit (e.g., R²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 0.863 | 0.421 | 0.984 |

| Logistic | 0.850 | 0.240 | 0.979 |

| Gumbel | 0.751 | 0.328 | 0.965 |

Step 3: HC5 Derivation

Objective: To use the fitted cumulative distribution function to calculate the HC5 value.

Protocol:

- Definition: The HC5 is the estimated concentration corresponding to the 5th percentile of the fitted SSD. This means that 5% of species in the model are expected to be affected at or below this concentration.

- Calculation: The HC5 is derived mathematically from the fitted distribution's inverse cumulative distribution function. For a Normal distribution with parameters μ and σ, the HC5 on the log10 scale is calculated as: HC5_log = μ - (1.645 * σ), where 1.645 is the z-score for the 5th percentile.

- Back-Transformation: Convert the log10-transformed HC5 back to a linear concentration to make it interpretable for environmental quality guidelines: HC5 = 10^(HC5_log).

Data Output: The final HC5 value in mg/L.

Table: HC5 Derivation from Different Fitted Distributions

| Distribution Type | HC5 (log10 scale) | HC5 (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 0.863 - (1.645 * 0.421) = 0.170 | 10^0.170 = 1.48 mg/L |

| Logistic | 0.850 - (1.645 * 0.240) = 0.455 | 10^0.455 = 2.85 mg/L |

| Gumbel | 0.751 - (1.645 * 0.328) = 0.212 | 10^0.212 = 1.63 mg/L |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and tools essential for conducting SSD-based research.

Table: Essential Reagents, Tools, and Software for SSD Development

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| US EPA SSD Toolbox | Software that simplifies the process of fitting, summarizing, visualizing, and interpreting SSDs [15]. | Supports multiple distributions (Normal, Logistic, etc.); available for download from the US EPA. |

| Toxicity Databases | Source of curated, quality-controlled ecotoxicological data for a wide range of chemicals and species. | US EPA ECOTOX Knowledgebase is a primary source for standardized test results. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | For performing advanced statistical analyses and custom model fitting if needed. | R, Python (with SciPy/NumPy), SAS, or similar platforms. |

| Normal Distribution | A symmetric, bell-shaped distribution commonly used as a default model in SSD analysis [15]. | Defined by parameters μ (mean) and σ (standard deviation). |

| Logistic Distribution | A symmetric distribution similar to the Normal distribution but with heavier tails, sometimes providing a better fit to toxicity data [15]. | Defined by parameters for location and scale. |

| 6-phospho-2-dehydro-D-gluconate | 6-phospho-2-dehydro-D-gluconate, MF:C6H11O10P, MW:274.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Narbomycin | Narbomycin, CAS:6036-25-5, MF:C28H47NO7, MW:509.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Analysis and Visualization

Once the basic SSD is constructed, the fitted curve is typically plotted to visualize the relationship between chemical concentration and the cumulative probability of species sensitivity. The following diagram illustrates the key components of a finalized SSD plot, including the derivation of the HC5.

Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs) are a foundational statistical tool in ecological risk assessment (ERA), used to determine safe concentrations of chemicals in surface waters by modeling the variation in sensitivity among different species [15]. These models fit a statistical distribution to toxicity data compiled from laboratory tests on various aquatic species, allowing regulators to infer a chemical concentration protective of a predetermined proportion of species in an aquatic community [15] [14]. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Species Sensitivity Distribution (SSD) Toolbox was developed to streamline this process, providing a consolidated platform with multiple algorithms for fitting, visualizing, summarizing, and interpreting SSDs, thereby supporting consistent and transparent risk assessments [15] [22] [14].

The SSD Toolbox represents a significant advancement in the evolution of ERAs by moving from simple models that treat all variation as random toward more sophisticated frameworks that can incorporate systematic biological differences [14]. Its development marks a step in the progression toward a third stage of ERA: ecosystem-level risk assessment, which aims to incorporate ecological structure and function into risk evaluations, moving beyond assessments focused solely on single species or communities [6]. The toolbox is designed to be accessible for both large and small datasets, making it a versatile resource for researchers and risk assessors [15].

The EPA SSD Toolbox operationalizes ecological risk assessment through a structured, three-step procedure that transforms raw toxicity data into protective environmental concentrations [15]. This workflow ensures a systematic approach to model development and interpretation.

Core Operational Procedure

The foundational workflow of the toolbox consists of three critical stages:

- Data Compilation: Toxicity test results for a specific chemical are gathered from various aquatic animal species, creating the dataset for analysis [15]. These typically include standard test organisms like Daphnia magna, Ceriodaphnia dubia, and Hyalella azteca, though the tool can accommodate other taxa, including fish and terrestrial vertebrates [14].

- Distribution Selection and Fitting: A statistical distribution is chosen and fit to the compiled toxicity data. The current version of the toolbox supports four distributions: Normal, Logistic, Triangular, and Gumbel [15].

- Protective Concentration Derivation: The fitted distribution is used to infer a concentration intended to protect a desired proportion of species in a hypothetical aquatic community, such as the HC5 (the concentration at which 5% of species are expected to be affected) [15].

This structured process helps risk assessors answer three fundamental questions: whether the appropriate analytical method is being used, whether the chosen distribution provides a good fit to the data, and whether the underlying assumptions of the analysis are met [14]. Answering these questions is crucial, as an ill-fitted distribution or violated assumptions can lead to biased conclusions and potentially misdirected regulatory actions [14].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points within the SSD Toolbox, from data input to final risk assessment output.

Diagram 1: The logical workflow and key decision points for using the US EPA SSD Toolbox.

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing the SSD Toolbox in research and regulatory contexts, including specific protocols for data preparation, model execution, and output interpretation.

Data Preparation and Input Protocol

The foundation of a robust SSD analysis is a high-quality, curated dataset. The following protocol outlines the essential steps for data preparation.

- Objective: To compile and format toxicity data for a target chemical, ensuring compatibility with the SSD Toolbox and the scientific validity of the subsequent analysis.

- Materials: The primary reagent for this stage is the Toxicity Database, typically sourced from the EPA's ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX) or other peer-reviewed literature. The SSD Toolbox software itself is the primary processing tool [15] [14].

- Procedure:

- Literature Search: Systematically search scientific databases (e.g., Web of Science, PubMed) and regulatory databases (e.g., ECOTOX) to gather published toxicity test results (endpoints such as LC50, EC50, NOEC) for the chemical of interest.

- Species Selection: Include data for a minimum of 8-10 species from at least three different taxonomic groups (e.g., fish, crustaceans, insects, algae) to ensure ecological diversity and a robust distribution [14] [6].

- Data Curation:

- Record the species name, toxicity endpoint, value, and exposure duration.

- Prioritize data from standardized test protocols (e.g., OECD, ASTM guidelines).

- For species with multiple values for the same endpoint, use the geometric mean to derive a single, representative value.

- Data Transformation: Log-transform the toxicity values (typically to base 10) to normalize the data, as species sensitivities often follow a log-normal distribution.

- Dataset Formatting: Structure the data in a table format (e.g., CSV) with clear column headers for import into the SSD Toolbox.

Model Fitting and HC5 Derivation Protocol

This core protocol details the steps for operating the SSD Toolbox to fit distributions and calculate protective concentrations.

- Objective: To fit multiple statistical distributions to the prepared toxicity dataset, evaluate their goodness-of-fit, and derive a statistically robust HC5 value.

- Materials: The SSD Toolbox software (downloadable from EPA Figshare or the Comptox Tools website) and the prepared toxicity dataset from Protocol 3.1 [15] [22].

- Procedure:

- Software Setup: Download and launch the SSD Toolbox. Create a new project and import the formatted toxicity dataset.

- Distribution Selection: Select the four available distributions (Normal, Logistic, Triangular, Gumbel) for comparative analysis [15].

- Model Execution: Run the toolbox to fit each selected distribution to the imported toxicity data. The software will automatically rank species by sensitivity and generate the cumulative distribution functions [14].

- Goodness-of-Fit Assessment: Examine the diagnostic plots and statistical metrics (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, AIC values) provided by the toolbox to determine which distribution best fits the data. The toolbox is specifically designed to help users confidently answer the question, "Is this distribution a good fit?" [14].

- HC5 Calculation: Using the best-fitting model, command the toolbox to calculate the HC5 (Hazard Concentration for the 5% most sensitive species) and its associated confidence interval. This value represents the concentration estimated to be protective of 95% of the species in the dataset.

Advanced Protocol: Incorporating Phylogeny and Taxonomy

The next generation of SSDs aims to incorporate systematic biological variation, such as phylogenetic relationships, to improve predictive accuracy.

- Objective: To evaluate if taxonomic group or phylogenetic relatedness explains patterns of sensitivity, which can help identify particularly vulnerable taxa and predict toxicity for data-poor species [14].

- Materials: The SSD Toolbox, a toxicity dataset, and phylogenetic information for the species in the dataset (available from databases like TimeTree or FishTree).

- Procedure:

- Taxonomic Grouping: Classify species in the dataset into broader taxonomic groups (e.g., algae/invertebrates/vertebrates or insects/crustaceans/fish) as demonstrated in ecosystem-level ERA research [6].

- Stratified Analysis: Use the toolbox's capabilities to visualize sensitivity across these different groups. Dr. Etterson, the lead EPA researcher, notes that incorporating phylogeny may help identify taxa at the greatest risk [14].

- Data Gap Analysis: If certain taxonomic groups are underrepresented, use the phylogenetic pattern to inform read-across predictions for untested species within related groups.

- Weighting: In advanced applications, weights can be assigned to different trophic levels based on relative biomass or exergy to move toward a system-level risk assessment, as proposed in ExSSD models [6].

Quantitative Data and Model Outputs

The SSD Toolbox generates quantitative outputs critical for decision-making. The tables below summarize key model parameters and a comparison of related tools.

Table 1: Key Statistical Distributions Supported by the EPA SSD Toolbox and Their Characteristics

| Distribution | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | ( f(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}} ) | Mean (μ), Standard Deviation (σ) | Standard model for data symmetrically distributed around the mean. |