Selecting Ecotoxicity Test Organisms: A Strategic Framework for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the strategic selection of ecotoxicity test organisms.

Selecting Ecotoxicity Test Organisms: A Strategic Framework for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the strategic selection of ecotoxicity test organisms. It bridges foundational principles with advanced applications, covering the core criteria for organism selection, established and emerging methodological approaches, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing test batteries, and the validation of methods for regulatory acceptance. By synthesizing current standards and future-oriented New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), this guide aims to enhance the ecological relevance, predictive power, and efficiency of environmental safety assessments in chemical and pharmaceutical development.

The Core Principles: Defining Ecotoxicity and Organism Selection Criteria

Ecotoxicology is a scientific discipline dedicated to understanding the effects of toxic chemical stressors on biological organisms, particularly within population, community, and ecosystem contexts. Regulatory and research agencies utilize ecotoxicity test data to assess hazards associated with substances that may be released into the environment, including industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, food additives, and color additives [1]. These data inform hazard assessments and evaluate potential risks to aquatic life (e.g., invertebrates, fish), birds, wildlife species, and the broader environment. The foundational principles of ecotoxicology integrate elements from ecology and toxicology to support chemical safety evaluations and environmental protection regulations worldwide.

Internationally, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Test Guidelines serve as the standard methods for non-clinical environment and health safety testing of chemicals and chemical products [2]. These guidelines are integral to the Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) system, which harmonizes testing across OECD member and adhering countries to avoid duplicative requirements. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed extensive Ecological Effects Test Guidelines under Series 850 to meet toxicity testing requirements for terrestrial and aquatic organisms under multiple statutory frameworks [3]. These standardized test methods ensure that chemical safety assessments are conducted with scientific rigor, reproducibility, and regulatory consistency across international jurisdictions.

Standardized Test Organisms and Methodologies

Standardized ecotoxicity tests utilize a diverse array of model organisms selected for their availability, adaptability to laboratory testing, potential to be tested at different life stages, low maintenance cost, historical data availability, and their capacity to represent broader ecological populations [1]. The selection of model species considers their "domain of applicability" and the conservation of toxicity-relevant biological traits between model species and ecological target species. The following table summarizes the primary test organisms and their applications in regulatory ecotoxicology:

Table 1: Standardized Test Organisms in Ecotoxicology

| Test Organism Group | Example Species | Common Test Guidelines | Measured Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquatic Invertebrates | Daphnia magna (water flea) | OECD 202, EPA 850.1010 | Acute immobilization, reproduction, growth |

| Fish | Oncorhynchus mykiss (rainbow trout) | OECD 203, 210, 236; EPA 850.1075 | Acute mortality, early life stage toxicity, embryo toxicity |

| Aquatic Plants | Lemna spp. (duckweed) | OECD 221, EPA 850.4400 | Growth inhibition, frond number, chlorophyll content |

| Algae | Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata | OECD 201, EPA 850.4500 | Growth inhibition, biomass yield |

| Terrestrial Invertebrates | Eisenia fetida (earthworm) | OECD 222, EPA 850.3100 | Survival, reproduction, growth |

| Birds | Colinus virginianus (bobwhite quail) | OECD 206, EPA 850.2100 | Acute oral toxicity, dietary toxicity, reproduction |

| Bees | Apis mellifera (honey bee) | OECD 213, 214; EPA 850.3020 | Acute contact toxicity, residual toxicity |

Recent updates to testing guidelines reflect scientific advancements and evolving regulatory needs. In June 2025, the OECD published 56 new, updated, and/or corrected test guidelines, including a new test guideline for acute toxicity to mason bees and updates to guidelines for acute and early life stage toxicity in fish and toxicity to aquatic plants [4]. These updates ensure testing keeps pace with scientific progress while promoting best practices aligned with the Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement (3Rs) principles for animal experimentation [2].

Criteria for Evaluating Ecotoxicity Studies

The reliability and relevance of ecotoxicity studies are critically evaluated before their use in regulatory decision-making. The Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data (CRED) project provides a framework to improve the reproducibility, transparency, and consistency of these evaluations [5]. According to the CRED framework, reliability concerns the inherent quality of a test report relating to standardized methodology and the clarity of experimental procedures and findings, while relevance addresses the appropriateness of data for a specific hazard identification or risk characterization purpose.

The U.S. EPA's Evaluation Guidelines for Ecological Toxicity Data in the Open Literature establish specific acceptance criteria for studies to be considered in ecological risk assessments [6]. For a study to be accepted, it must meet these minimum criteria:

- The toxic effects are related to single chemical exposure

- The toxic effects are on an aquatic or terrestrial plant or animal species

- There is a biological effect on live, whole organisms

- A concurrent environmental chemical concentration/dose or application rate is reported

- There is an explicit duration of exposure

- The article is published in English as a full, publicly available primary source

- A calculated endpoint is reported with treatments compared to an acceptable control

- The study location and tested species are reported and verified

Table 2: Study Evaluation Criteria Comparison

| Evaluation Aspect | Klimisch Method | CRED Criteria | EPA Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability Focus | GLP compliance, standardized methods | Study design, performance, analysis | Experimental design, control comparison |

| Relevance Assessment | Limited guidance | Purpose-specific assessment | Problem formulation-driven |

| Transparency | Limited criteria | 20 reliability, 13 relevance criteria | 14 specific acceptance criteria |

| Documentation | Score (1-4) | Detailed evaluation guidance | Open Literature Review Summary (OLRS) |

| Application Flexibility | Rigid categorization | Adaptable to various study types | Focused on regulatory risk assessment |

The evolution from the traditional Klimisch method to more comprehensive frameworks like CRED addresses previous limitations in specificity, essential criteria, and guidance for both reliability and relevance evaluations [5]. This progression enables more consistent and transparent regulatory decisions based on scientific evidence.

Advanced Methodologies and Emerging Approaches

Molecular Ecotoxicology and Omics Technologies

Molecular tools and omics technologies are transforming ecotoxicology by providing deeper mechanistic understanding of toxicological pathways. The SETAC Europe 2025 session on Molecular Ecotoxicology and Omics Perspectives highlighted advances in transcriptomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, and proteomics that contribute to environmental risk assessment [7]. These approaches enable researchers to identify molecular initiating events in adverse outcome pathways and develop more predictive toxicity assessments.

Transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPOD) has emerged as a promising method to derive quantitative threshold values from RNAseq data. In the case of tamoxifen effects in zebrafish, the tPOD derived from zebrafish embryos was in the same order of magnitude but slightly more sensitive than the NOEC from a two-generation study [7]. Similarly, comparisons of tPODs estimated in rainbow trout alevins with conventional fish toxicity tests showed that tPOD values were equally or more conservative than values from chronic tests, supporting their use as alternative methods aligned with 3R principles.

Toxicokinetic-Toxicodynamic (TKTD) Modeling

The application of General Unified Threshold Models of Survival (GUTS) represents a significant advancement in ecotoxicological modeling. These models integrate toxicokinetic (what the organism does to the chemical) and toxicodynamic (what the chemical does to the organism) processes to predict survival under time-variable exposure scenarios [8]. Recent research comparing visual assessment and quantitative goodness-of-fit metrics on GUTS model fits found that quantitative indices and visual assessments generally agreed on model performance, with dose-response curve plots tending to be scored better than time series representations of the same data.

The OECD's recent updates to several test guidelines now allow collection of tissue samples for omics analysis, including Test No. 203 (Fish Acute Toxicity Test), Test No. 210 (Fish Early-life Stage Toxicity Test), and Test No. 236 (Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity Test) [9]. This integration of traditional and advanced methodologies enhances the mechanistic understanding of toxic effects while supporting the development of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs).

Experimental Protocols in Ecotoxicology

Standardized Aquatic Toxicity Test Protocol: Daphnia Acute Immobilization Test

Principle: This test assesses the acute toxicity of chemicals to the freshwater cladoceran Daphnia magna or Daphnia pulex by determining the concentration that causes 50% immobilization (EC50) after 48 hours of exposure [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test Chambers: 50-100 mL glass beakers or disposable plastic vessels

- Reconstituted Water: Standardized freshwater with defined hardness, pH, and alkalinity

- Daphnia Cultures: Neonates (<24 hours old) from laboratory cultures

- Aeration System: To maintain dissolved oxygen near saturation

- Test Substance: Analytical grade chemical with known purity

- Dilution Water: Reconstituted freshwater for preparing concentration series

Procedure:

- Prepare at least five concentrations of the test substance in geometric series, plus control(s)

- Randomly assign 10 daphnids to each test chamber with 50 mL test solution

- Maintain test chambers at 20±2°C with a 16:8 hour light:dark photoperiod

- Do not feed organisms during the 48-hour test period

- Record immobilization (lack of movement after gentle agitation) at 24 and 48 hours

- Measure actual chemical concentrations at test initiation and periodically throughout

- Calculate EC50 values using appropriate statistical methods (e.g., probit analysis)

Quality Control:

- Immobilization in control groups must not exceed 10%

- Dissolved oxygen concentration must remain ≥60% saturation

- Temperature variation should not exceed ±2°C

- Test validity requires reference toxicant EC50 within established historical range

Terrestrial Plant Toxicity Test: Seedling Emergence and Seedling Growth

Principle: This test assesses the effects of chemicals on seedling emergence and early growth of terrestrial plants exposed to treated soil or substrate [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test Species: Two monocotyledonous and two dicotyledonous species (e.g., ryegrass, oat, radish, lettuce)

- Test Substrate: Standardized soil with known properties or natural soil

- Growth Chambers: Controlled environment with adjustable light, temperature, humidity

- Application Equipment: Precision sprayer or incorporation system for test substance

- Measurement Tools: Calipers, drying oven, analytical balance

Procedure:

- Mix test substance with soil to create a concentration series

- Place soil in appropriate containers and plant seeds at recommended depths

- Maintain appropriate moisture and environmental conditions for specific species

- Record seedling emergence daily until control plants reach certain growth stage

- Harvest plants at test termination (typically 14-21 days after emergence)

- Measure endpoints: emergence, shoot height, visible phytotoxicity, biomass

Data Analysis:

- Calculate EC25 and EC50 values for emergence and growth measurements

- Determine NOEC and LOEC using appropriate statistical tests

- Evaluate dose-response relationships for each species and endpoint

Visualization of Ecotoxicology Testing Framework

The following diagram illustrates the integrated framework for ecotoxicology testing and assessment, highlighting the relationships between standardized testing, advanced methodologies, and regulatory applications:

Ecotoxicology Testing and Assessment Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ecotoxicology Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstituted Freshwater | Standardized aqueous medium for aquatic tests | Daphnia and fish toxicity tests [1] |

| Standard Reference Toxicants | Quality control and laboratory proficiency assessment | Potassium dichromate for Daphnia, sodium chloride for fish |

| Formulated Sediments | Standardized substrate for benthic organism tests | Chironomid and amphipod sediment toxicity tests |

| Cryopreservation Media | Long-term storage of cells and tissues for omics analysis | Tissue banking for transcriptomic and proteomic studies [9] |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preservation of RNA integrity for transcriptomics | tPOD determination in fish embryos [7] |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Biomarker response quantification | Acetylcholinesterase inhibition for neurotoxicity |

| Cell Culture Media | Maintenance of in vitro systems | Fish cell lines for alternative toxicity testing |

| Chemical Analysis Standards | Analytical quantification and method validation | HPLC/GC-MS analysis of test substance concentrations |

| Toripristone | Toripristone, CAS:91935-26-1, MF:C31H39NO2, MW:457.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Saframycin H | Saframycin H, CAS:92569-01-2, MF:C32H36N4O9, MW:620.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Ecotoxicology continues to evolve from traditional whole-organism toxicity testing toward integrated approaches that incorporate mechanistic understanding through molecular techniques and predictive modeling. The selection of test organisms remains guided by their representativeness of ecological communities, practical laboratory considerations, and regulatory requirements. Recent advances in omics technologies and computational toxicology are enhancing the scientific basis for chemical risk assessment while supporting the implementation of 3R principles. The ongoing development of internationally harmonized test guidelines ensures that ecotoxicity testing maintains scientific rigor while adapting to technological innovations and changing regulatory needs. As the field progresses, the integration of standardized testing with New Approach Methodologies will continue to refine our ability to protect ecosystems from chemical stressors while reducing reliance on animal testing.

Ecotoxicity testing relies on a compartmentalized view of the environment to assess the potential adverse effects of chemicals on ecosystems. The aquatic, sediment, and terrestrial compartments represent distinct but interconnected environments, each hosting unique biological communities and posing specific challenges for ecotoxicological assessment. Understanding the structural and functional characteristics of these compartments is fundamental to selecting appropriate test organisms and designing relevant testing protocols. This framework is essential for developing accurate ecological risk assessments that protect ecosystem health while advancing the goals of chemical and pharmaceutical regulation.

The Aquatic Compartment

Compartment Characteristics and Ecological Relevance

The aquatic compartment includes freshwater, estuarine, and marine ecosystems characterized by the dominance of water as the medium for biological processes. This compartment serves as a primary recipient for many environmental contaminants through direct discharge, surface runoff, and atmospheric deposition [10]. From an ecotoxicological perspective, the aquatic environment presents unique challenges due to the high mobility of contaminants, complex exposure pathways, and the sensitivity of aquatic organisms to dissolved pollutants. The compartment's high connectivity facilitates contaminant dispersal across large geographical areas, making it particularly vulnerable to pollution events [11].

Aquatic ecosystems are characterized by distinct vertical stratification (water column vs. benthic zones) and horizontal connectivity (rivers, lakes, oceans), which influence both exposure scenarios and ecological effects. The physicochemical properties of water (pH, hardness, temperature, dissolved organic carbon) significantly modify chemical bioavailability and toxicity, necessitating standardized testing conditions to ensure reproducible results [12].

Standard Test Organisms and Selection Criteria

Regulatory guidelines for aquatic ecotoxicity testing employ standardized test species selected for their ecological relevance, sensitivity to contaminants, and practicality for laboratory culture. These surrogate species represent different trophic levels and taxonomic groups within aquatic ecosystems [12].

- Freshwater Fish: Standard test species include rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) as a cold-water species and bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus) as a warm-water species. These vertebrate species are used in acute (96-hour LC50) and chronic (early life-stage) tests, providing data on mortality, growth, and reproductive impacts [12].

- Aquatic Invertebrates: The water flea (Daphnia magna or D. pulex) is a cornerstone of aquatic testing, serving as a representative of freshwater invertebrates. Its particulate feeding behavior, transparent body, and parthenogenetic reproduction make it ideal for acute (48-hour EC50) and chronic (21-day reproduction) tests [12].

- Aquatic Plants: Algae (e.g., Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata, formerly Selenastrum capricornutum) and aquatic vascular plants (e.g., Lemna gibba, duckweed) are used to assess phytotoxicity. Algal growth inhibition tests (72-96 hour EC50) evaluate impacts on primary producers, which form the base of aquatic food webs [12].

Table 1: Standard Aquatic Test Organisms and Endpoints

| Test Organism | Test Type | Standard Duration | Primary Endpoints | Guideline Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | Acute Toxicity | 96 hours | LC50 (Lethal Concentration) | OECD 203 |

| Water Flea (Daphnia magna) | Acute Toxicity | 48 hours | EC50 (Immobilization) | OECD 202 |

| Water Flea (Daphnia magna) | Chronic Toxicity | 21 days | NOEC/LOEC (Reproduction) | OECD 211 |

| Freshwater Algae (Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata) | Growth Inhibition | 72-96 hours | EC50 (Biomass) | OECD 201 |

| Fathead Minnow (Pimephales promelas) | Early Life-Stage | 28-32 days | Hatchability, Growth, Survival | OECD 210 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Acute Toxicity Test withDaphnia magna

Principle: Young daphnids, aged less than 24 hours at test initiation, are exposed to a range of concentrations of the test substance diluted in reconstituted water. The immobility (the inability to swim) is recorded after 48 hours and compared with control values to determine the EC50 [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test Organism: Daphnia magna, neonates (<24 hours old) from healthy, cultured populations

- Test Substance: Known concentration and purity, with appropriate solvent controls if necessary

- Reconstituted Water: Standardized water with defined hardness, pH, and alkalinity (e.g., EPA Moderately Hard Water)

- Test Chambers: Glass or chemically inert vessels, typically 50-100 mL capacity

- Environmental Chamber: Maintained at 20°C ± 2°C with a 16:8 hour light:dark cycle

- Aeration System: For oxygen saturation (if required for static-renewal tests)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of the test substance and dilute it to at least five concentrations, preferably in a geometric series. Prepare a control (and solvent control if applicable).

- Randomization: Randomly assign at least 10 daphnids to each test chamber, with four replicates per concentration.

- Exposure: Add the daphnids to the test chambers containing 50 mL of the respective test solution. Do not feed the organisms during the 48-hour test.

- Monitoring: Record temperature and dissolved oxygen at the beginning and end of the test. Check pH in the control and highest concentration.

- Endpoint Assessment: After 48 hours, record the number of immobile daphnids in each chamber. Gently agitate the water to stimulate movement if necessary. An organism is considered immobile if it fails to resume swimming.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the EC50 value using appropriate statistical methods (e.g., Probit analysis, Trimmed Spearman-Karber).

Quality Control:

- Control mortality must not exceed 10%.

- Test temperature must remain within 20°C ± 2°C.

- Dissolved oxygen concentration must be ≥ 60% saturation at the end of the test.

The Sediment Compartment

Compartment Characteristics and Ecological Relevance

Sediments represent the depositional environment at the bottom of water bodies, forming a critical interface between the water column and the benthic zone. This compartment acts as a long-term sink for hydrophobic contaminants, heavy metals, and other pollutants that adsorb to particulate matter [10] [13]. Sediment-bound contaminants can persist for decades, creating a legacy of pollution that continues to impact ecosystems long after primary sources are controlled. The sediment compartment is characterized by reducing conditions and distinct physicochemical gradients (e.g., oxygen, pH, redox potential) that dramatically influence the bioavailability and transformation of contaminants [13].

The bioavailability of sediment-associated contaminants depends on multiple factors, including sediment composition (grain size, organic carbon content), pore water chemistry, and biological traits of sediment-dwelling organisms. This complexity necessitates testing approaches that consider the whole sediment matrix rather than aqueous exposures alone [13].

Standard Test Organisms and Selection Criteria

Sediment test organisms are primarily benthic invertebrates that live in or on sediments and have direct, prolonged contact with contaminated sediments. They are selected based on their ecological relevance, sensitivity, sediment-processing behavior, and trophic level [13].

- Amphipods: Marine and estuarine amphipods (e.g., Leptocheirus plumulosus, Ampelisca abdita) and freshwater amphipods (e.g., Hyalella azteca) are widely used in whole-sediment tests. Their burrowing and feeding activities make them highly exposed to sediment contaminants [13].

- Midges: The larvae of the dipteran Chironomus riparius (freshwater) or C. dilutus are key test organisms. As deposit-feeders that construct sediment tubes, they are directly exposed to contaminants throughout their larval development, making them ideal for life-cycle tests [12].

- Oligochaetes: Freshwater worms (e.g., Lumbriculus variegatus) and marine polychaetes (e.g., Neanthes arenaceodentata) are used in bioaccumulation and toxicity tests. Their sediment-ingesting behavior provides a critical exposure route for assessing trophic transfer [13].

Table 2: Standard Sediment Test Organisms and Endpoints

| Test Organism | Test Type | Standard Duration | Primary Endpoints | Guideline Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater Amphipod (Hyalella azteca) | Whole-Sediment Toxicity | 10-28 days | Survival, Growth | EPA 600-R-99-064 |

| Freshwater Midge (Chironomus dilutus) | Whole-Sediment Toxicity | 10-20 days | Survival, Growth, Emergence | OECD 218/219 |

| Marine Amphipod (Leptocheirus plumulosus) | Whole-Sediment Toxicity | 10-28 days | Survival, Growth | EPA 600-R-99-064 |

| Freshwater Oligochaete (Lumbriculus variegatus) | Bioaccumulation | 28 days | Bioaccumulation Factor (BAF) | OECD 315 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Whole-Sediment Toxicity Test withChironomus dilutus

Principle: This test evaluates the toxicity of contaminated field-collected or spiked sediments by exposing first-instar Chironomus larvae for a period of 10-20 days. Endpoints include survival, growth (ash-free dry weight), and for longer tests, emergence to adulthood [13].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test Organism: First-instar Chironomus dilutus larvae (<24 hours old)

- Test Sediment: Field-collected or laboratory-spiked sediment, characterized for particle size, organic carbon, and moisture content

- Reference Sediment: A clean, uncontaminated sediment with similar characteristics

- Overlying Water: Reconstituted or site water appropriate for the test species

- Test Chambers: 300-mL to 1-L beakers filled with 2 cm of sediment and 600-800 mL of overlying water

- Aeration System: Gentle aeration to maintain oxygen without disturbing the sediment surface

- Food Supply: Suspended fish food or other appropriate diet

Procedure:

- Test Setup: Place the test sediment into replicate test chambers to a depth of approximately 2 cm. Carefully add overlying water without disturbing the sediment surface. Allow chambers to equilibrate for 2-3 days before adding organisms.

- Organism Introduction: Randomly assign 10-20 first-instar larvae to each test chamber.

- Test Maintenance: Maintain test systems at 23°C ± 1°C with a 16:8 hour light:dark cycle. Feed larvae a defined amount of fish food suspension daily. Monitor and record water quality parameters (temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, ammonia) regularly.

- Renewal: For longer tests (e.g., 20-day), consider renewing the overlying water periodically while minimizing sediment disturbance.

- Termination and Endpoint Assessment: After 10 days, carefully sieve the contents of each chamber to retrieve the larvae. Count the number of surviving organisms and determine the ash-free dry weight per replicate to assess growth. For 20-day tests, also record the number of emerged adults.

Quality Control:

- Survival in the control sediment must be ≥ 80%.

- Growth in the control sediment must meet minimum acceptable levels (e.g., ≥ 0.45 mg ash-free dry weight per organism for C. dilutus).

- Overlying water dissolved oxygen must remain ≥ 2.5 mg/L near the sediment-water interface.

The Terrestrial Compartment

Compartment Characteristics and Ecological Relevance

The terrestrial compartment encompasses the soil ecosystem and the above-ground habitats it supports. Soil is a complex, heterogeneous matrix comprising mineral particles, organic matter, water, air, and a vast diversity of organisms. This compartment receives contaminants through pesticide applications, atmospheric deposition, waste disposal, and accidental spills [10]. The fate and effects of chemicals in terrestrial systems are governed by soil properties such as texture, pH, cation exchange capacity, and organic matter content, which collectively influence a chemical's mobility, persistence, and bioavailability [14].

Unlike aquatic systems where exposure occurs primarily through water, terrestrial organisms face multiple exposure routes: direct contact with soil, ingestion of soil or contaminated food, and inhalation of soil pore air. This complexity requires careful consideration in test design and organism selection [14].

Standard Test Organisms and Selection Criteria

Terrestrial test organisms are selected to represent different functional groups, trophic levels, and exposure pathways within soil ecosystems. Standard tests focus on plants, soil invertebrates, and pollinators, which play critical roles in ecosystem functioning [12] [14].

- Plants: Terrestrial plants, typically monocotyledons (e.g., oat, Avena sativa) and dicotyledons (e.g., lettuce, Lactuca sativa), are used in seedling emergence and vegetative vigor tests. They represent primary producers and assess impacts on germination and growth [12].

- Earthworms: The earthworm Eisenia fetida is the standard test species for soil invertebrate testing. As soil-ingesting organisms that constantly interact with the soil matrix, they are highly exposed to soil contaminants and serve as key indicators of soil health [12].

- Birds: Avian species such as the Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) and Mallard Duck (Anas platyrhynchos) are used in acute oral and dietary tests, representing vertebrate wildlife exposed through contaminated food and water [12].

- Bees: The honey bee (Apis mellifera) is a standard test organism for evaluating pesticide risks to pollinators, assessing both acute contact toxicity and residual toxicity on foliage [12] [15].

Table 3: Standard Terrestrial Test Organisms and Endpoints

| Test Organism | Test Type | Standard Duration | Primary Endpoints | Guideline Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earthworm (Eisenia fetida) | Acute Toxicity | 14 days | LC50 (Mortality) | OECD 207 |

| Earthworm (Eisenia fetida) | Reproduction | 56 days | NOEC (Reproduction) | OECD 222 |

| Terrestrial Plants (e.g., Lettuce, Oat) | Seedling Emergence/Vigor | 14-21 days | EC25 (Emergence, Biomass) | OECD 208 |

| Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) | Acute Contact | 48-96 hours | LD50 (Mortality) | OECD 214 |

| Mason Bee (Osmia sp.) | Acute Contact | 48-96 hours | LD50 (Mortality) | OECD 254 |

| Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) | Acute Oral | 14 days | LD50 (Mortality) | OECD 223 |

| Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) | Reproduction | 20 weeks | NOAEC (Reproduction) | OCSPP 850.2300 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Earthworm Acute Toxicity Test

Principle: Adult earthworms (Eisenia fetida) are exposed to a range of concentrations of a test substance mixed into an artificial soil substrate. Mortality is assessed after 14 days to determine the LC50 [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test Organism: Mature Eisenia fetida with a well-developed clitellum

- Artificial Soil: A standardized mixture of 10% sphagnum peat, 20% kaolinite clay, and 70% industrial sand, adjusted to pH 6.0 ± 0.5 with calcium carbonate

- Test Substance: Known concentration and purity

- Test Containers: 1-L glass or plastic containers with perforated lids for aeration

- Environmental Chamber: Maintained at 20°C ± 2°C with continuous dim light

- Food Supply: A small amount of dried, powdered mammal fodder or oatmeal

Procedure:

- Soil Preparation: Prepare the artificial soil and moisten it to approximately 40-60% of the maximum water-holding capacity. Mix the test substance into the soil in a geometric series of at least five concentrations.

- Test Initiation: Place 500 g (wet weight) of the treated soil into each test container. Introduce 10 adult earthworms, which have been rinsed and briefly blotted dry, into each container.

- Test Maintenance: Maintain the test containers in the environmental chamber for 14 days. Feed the worms a small amount of food (e.g., 5 g of oatmeal) at the start of the test and after one week.

- Monitoring: Weigh containers weekly and replenish water to maintain constant moisture. Check for and remove any dead worms every 24-48 hours during the first week and at day 7 and 14.

- Termination and Assessment: After 14 days, carefully empty the soil from each container and count the number of surviving worms. A worm is considered dead if it does not respond to a gentle mechanical stimulus.

Quality Control:

- Control mortality must not exceed 10%.

- The average individual weight loss of worms in the control should not exceed 20%.

- Soil pH should be measured in the control and highest concentration at the start and end of the test.

Integrated Testing Strategies and Emerging Approaches

The Watershed as an Integrative Unit

Recent frameworks advocate for moving beyond isolated compartment testing toward integrated approaches that reflect ecological reality. The Net Watershed Exchange (NWE) concept uses the watershed as the fundamental spatial unit, integrating all terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and their hydrologic carbon exchanges [16]. This approach helps bridge gaps between land- and atmosphere-based carbon flux estimates and addresses the challenge of lateral carbon transfer, where carbon fixed in terrestrial ecosystems is transported to aquatic systems [16] [11]. Applying this landscape perspective to ecotoxicity can improve risk assessment by accounting for cross-compartment contaminant transfers.

(Q)SAR and In Silico Methods

With increasing regulatory restrictions on animal testing, computational approaches are gaining prominence for preliminary screening. (Quantitative) Structure-Activity Relationship ((Q)SAR) models predict environmental fate parameters (e.g., Persistence, Bioaccumulation) and toxicity based on a chemical's structural properties [17]. Tools like VEGA, EPI Suite, and TEST provide valuable data for filling information gaps, with their reliability heavily dependent on the Applicability Domain (AD) of the model [17].

Omics and Advanced Methodologies

Updated OECD Test Guidelines (e.g., Test No. 203, 210, 236) now allow for the collection of tissue samples for omics analysis, providing deeper mechanistic insights into biological responses to chemical exposure at the molecular level [15]. Furthermore, the inclusion of new test species like the Mason bee (Osmia sp.) in OECD Test Guideline 254 reflects efforts to address biodiversity and protect key ecosystem services like pollination [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Ecotoxicity Testing

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstituted Water | Provides a standardized, reproducible aqueous medium for aquatic tests. | EPA Moderately Hard Water: Specific recipe of salts to control hardness, alkalinity, and pH. |

| Artificial Soil | Standardized substrate for terrestrial tests with earthworms and other soil invertebrates. | OECD formulation: 10% peat, 20% kaolinite clay, 70% industrial sand, pH adjusted to 6.0. |

| Control Sediments | Provide a baseline for comparing effects in sediment tests; can be clean reference sediments or formulated sediments. | Characterized for key parameters like particle size distribution, organic carbon content, and pH. |

| Standard Test Diets | Nutritionally consistent food for maintaining test organisms during culture and testing. | Examples: Fish food flakes for daphnia, powdered oatmeal for earthworms, specific pollen mixes for bees. |

| Solvent Carriers | Used to dissolve poorly water-soluble test substances for dosing. | Solvents like acetone, dimethyl formamide (DMF); must be non-toxic at concentrations used and include solvent controls. |

| Chemical Standards | Pure substances of known concentration and identity used for test substance verification and analytical calibration. | Critical for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of dosing in both definitive tests and range-finding studies. |

| Prolylrapamycin | Prolylrapamycin | Prolylrapamycin is an analog of Rapamycin (Sirolimus) for mTOR signaling pathway research. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for personal use. |

| 6-Benzoylheteratisine | 6-Benzoylheteratisine, CAS:99759-48-5, MF:C29H37NO6, MW:495.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Ecotoxicity Testing Workflows and Conceptual Frameworks

Diagram 1: Standard Aquatic Toxicity Testing Workflow

Diagram 2: Landscape-Scale Contaminant Transfer Between Compartments

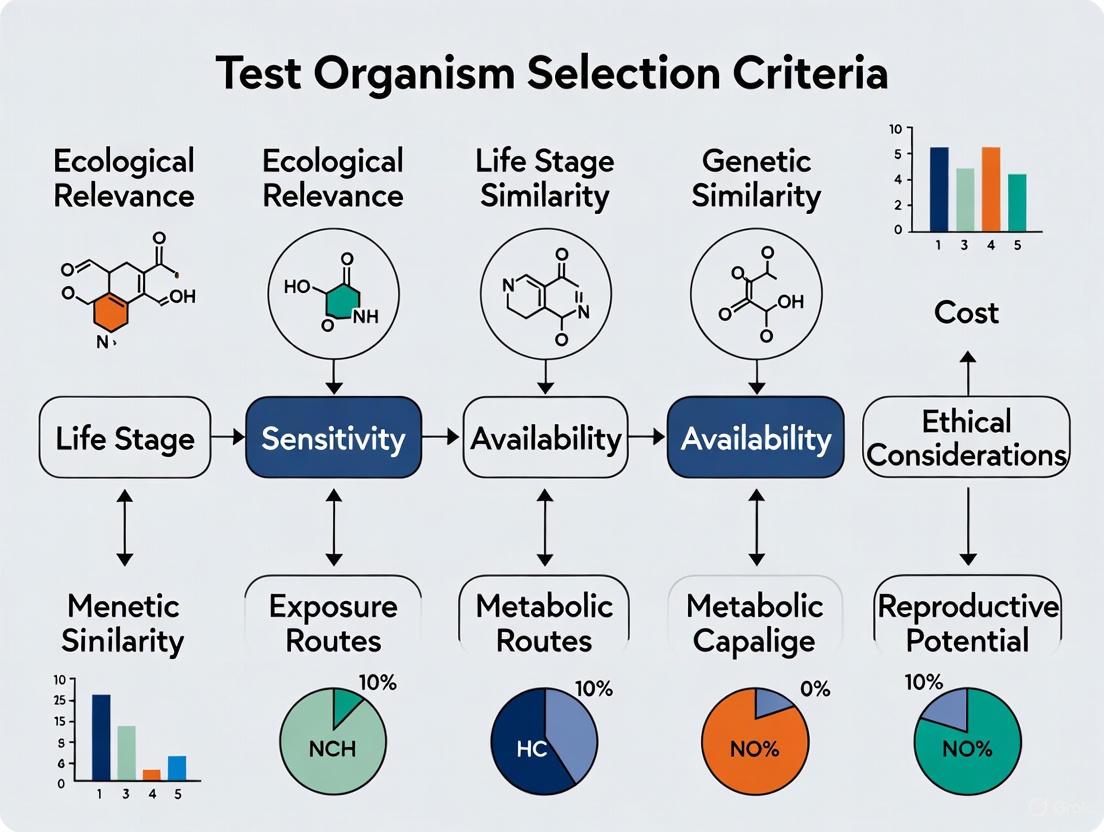

Application Note: Foundational Principles for Test Organism Selection

The selection of appropriate test organisms is a critical initial step in ecological risk assessment (ERA), as their responses to chemical exposure serve as predictive evidence of potential environmental impacts [18]. The foundational principle guiding selection is that test species should be representative of the ecosystem being assessed, with physiological traits adapted to the specific region [18]. Regulatory frameworks worldwide, including the U.S. Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), mandate ecological effects testing as part of pesticide registration processes, requiring manufacturers to conduct, analyze, and fund numerous scientific tests to demonstrate safety for nontarget wildlife [19]. These regulatory processes increasingly consider data from open literature alongside standardized guideline studies, particularly for assessing impacts on threatened and endangered species [6].

Core Selection Criteria Framework

The essential criteria for selecting ecotoxicity test organisms form an interconnected framework ensuring ecological relevance, regulatory acceptance, and practical feasibility. The most critical criteria encompass:

Taxonomic Identification and Clarity: Species must have verified taxonomy and well-analyzed morphological and physiological traits, including life cycle and reproduction patterns [18] [5]. Proper taxonomic identification ensures reproducibility and allows for meaningful interspecies comparisons.

Geographical Distribution and Habitat Representation: Organisms should be representative of the specific geographical region of interest [18]. Species native to the assessment area provide more relevant data, especially when site-specific information is required [18].

Ecological Role and Trophic Level Position: Test species should occupy defined positions within ecological communities, representing specific trophic levels (e.g., producers, primary consumers, secondary consumers, decomposers) and fulfilling important ecological functions [20] [18]. Selecting species from multiple trophic levels provides a more comprehensive assessment of potential ecosystem impacts.

Laboratory Adaptability and Culture Potential: Practical considerations include ease of manipulation, small size, short life cycle, and established culture methods [18] [19]. Species must adapt to laboratory conditions while maintaining ecological relevance.

Sensitivity to Chemical Exposure: Organisms should demonstrate appropriate susceptibility to environmental contaminants to provide protective assessment outcomes [18]. A range of sensitivities across tested species helps establish protective thresholds.

Standardized Method Availability: Well-established, scientifically accepted testing methodologies must be available for the species to ensure consistency and comparability of results [5] [19].

Table 1: Essential Selection Criteria for Ecotoxicity Test Organisms

| Criterion Category | Specific Requirements | Regulatory/Assessment Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy | Clear taxonomy; Well-analyzed morphological and physiological traits; Known life cycle and reproduction patterns | Ensures reproducibility and allows for meaningful interspecies comparisons and extrapolations |

| Distribution | Representative of geographical region of interest; Native to assessment area; Defined habitat type | Provides regionally relevant data for site-specific assessments |

| Ecological Role | Defined position in trophic level; Important ecological function; Role in nutrient cycling or as habitat provider | Represents ecosystem structure and function; Captures food web interactions |

| Practical Considerations | Ease of laboratory culture; Short life cycle; Small size; Established testing methodologies | Ensures feasibility and standardization of testing protocols |

Experimental Protocols: Implementation and Evaluation

Protocol for Criteria-Based Test Species Selection

Purpose and Scope

This protocol provides a systematic approach for selecting ecotoxicity test organisms based on the essential criteria of taxonomy, distribution, and ecological role. The methodology aligns with international standards for ecological risk assessment while allowing for region-specific adaptations [18] [5].

Materials and Equipment

- Geographical distribution maps and ecological databases

- Taxonomic identification keys and verification resources

- Ecological niche modeling software (optional)

- Laboratory culture facilities appropriate for candidate species

- Reference toxicants for sensitivity validation

Procedure

Step 1: Compile Candidate Species List

- Identify potential test species through literature review of ecological studies in the target region [18]

- Consult taxonomic databases to verify nomenclature and phylogenetic relationships

- Document known physiological traits, habitat preferences, and ecological functions for each candidate

Step 2: Evaluate Taxonomic Suitability

- Verify taxonomic classification using authoritative databases

- Assess availability of morphological and life history data

- Confirm that identification keys exist for reliable species recognition

Step 3: Assess Geographical Distribution

- Map current and historical distribution patterns within the target assessment region [18]

- Evaluate population status and conservation concerns

- Determine habitat specificity and environmental tolerance ranges

Step 4: Characterize Ecological Role

- Identify trophic level position (producer, primary consumer, secondary consumer, decomposer) [20]

- Document role in nutrient cycling, energy flow, or habitat provision [18]

- Assess importance in food web dynamics and ecosystem function

Step 5: Evaluate Practical Implementation Factors

- Assess ease of collection and laboratory acclimation

- Develop or adapt culture methods maintaining genetic diversity

- Establish life cycle parameters and reproductive characteristics under controlled conditions [18]

Step 6: Validate Sensitivity and Response Characteristics

- Conduct range-finding tests with reference toxicants

- Compare sensitivity to known standard test species

- Evaluate consistency of response across multiple life stages

Step 7: Document and Review Selection Justification

- Compile complete assessment against all selection criteria

- Identify potential limitations and research needs

- Establish standardized testing protocols for selected species

Protocol for Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data Quality

Purpose and Scope

This protocol outlines procedures for evaluating the reliability and relevance of ecotoxicity studies based on the CRED (Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data) framework, which provides transparent criteria for assessing study quality [5].

Materials

- CRED evaluation checklist (20 reliability criteria, 13 relevance criteria) [5]

- Study evaluation tracking system

- Taxonomic verification resources

- Statistical analysis software

Procedure

Step 1: Initial Relevance Screening

- Assess appropriateness of test species for specific assessment purpose

- Evaluate match between test endpoints and assessment goals

- Determine environmental relevance of exposure conditions

Step 2: Reliability Assessment

- Evaluate experimental design (controls, replicates, concentration series)

- Assess chemical characterization and exposure verification

- Review statistical analysis and endpoint derivation methods

- Verify organism health and test condition documentation

Step 3: Taxonomic Verification

- Confirm test organism identification and source

- Assess life stage and health status appropriateness

- Document any genetic or population-specific characteristics

Step 4: Geographical and Ecological Context Evaluation

- Assess environmental relevance of test conditions to assessment scenario

- Evaluate appropriateness of species for specific ecosystem being assessed

- Consider seasonal and life cycle factors in experimental timing

Step 5: Data Quality Integration

- Categorize studies based on reliability and relevance assessments

- Identify data gaps and uncertainties

- Determine suitability for quantitative or qualitative use in risk assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Resources for Ecotoxicity Test Species Selection

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Selection Process |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Databases | NCBI Taxonomy Database; Regional species inventories; Taxonomic keys | Verification of species identification; Phylogenetic relationship analysis |

| Distribution Mapping Tools | Geographical Information Systems (GIS); Species distribution models; Ecological atlases | Determination of geographical representation; Habitat suitability assessment |

| Ecological Role References | Trophic level classifications; Food web studies; Ecological trait databases | Characterization of ecosystem function; Trophic position assessment |

| Culture System Components | Aquaculture systems; Climate-controlled chambers; Specialized feed formulations | Laboratory adaptation and maintenance; Life cycle studies under controlled conditions |

| Reference Toxicants | Sodium dodecyl sulfate; Sodium nitrite; Copper salts [21] | Sensitivity validation; Method standardization and quality control |

| Data Quality Assessment Tools | CRED evaluation checklist [5]; EPA ECOTOX acceptance criteria [6] | Reliability and relevance assessment of existing ecotoxicity studies |

| Zoledronate disodium | Zoledronate Disodium | Zoledronate disodium salt for research. Study bone biology, osteoporosis, and cancer metastases. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Nepetoidin B | Nepetoidin B, MF:C17H14O6, MW:314.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Integration Approaches

Species Sensitivity Distribution Modeling

The selection of appropriate test species directly influences the development of Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs), which statistically aggregate toxicity data to quantify the distribution of species sensitivities and estimate hazardous concentrations (e.g., HC5, the concentration affecting 5% of species) [20]. SSDs built using species representing multiple taxonomic groups and trophic levels provide more robust and protective risk assessments [20] [21]. Research demonstrates that global and class-specific SSD models can be developed using curated datasets spanning multiple taxonomic groups across four trophic levels: producers (e.g., algae), primary consumers (e.g., insects), secondary consumers (e.g., amphibians), and decomposers (e.g., fungi) [20].

Addressing Regional Representation Gaps

Current international test guidelines predominantly feature species from North America and Europe, creating significant gaps for assessments in other regions like East Asia [18]. Research identifies promising region-specific test species including Zacco platypus, Misgurnus anguillicaudatus, Hydrilla verticillata, Neocaridina denticulata spp., and Scenedesmus obliquus for East Asian assessments [18]. These species demonstrate how regional selection criteria application can address geographical representation gaps in ecotoxicity testing.

Emerging Approaches and Future Directions

New approach methodologies (NAMs) are increasingly important for addressing data gaps while reducing animal testing [20] [1]. Machine learning techniques, such as pairwise learning applied to chemical-species pairs, can predict sensitivity and help prioritize testing needs [22]. Additionally, the CRED framework provides standardized evaluation criteria that improve the reproducibility, transparency, and consistency of reliability and relevance evaluations for ecotoxicity studies [5].

The selection of appropriate test organisms is a critical determinant of success in ecotoxicity testing. The ideal model organism must not only exhibit biological relevance to the assessment endpoint but also demonstrate practical adaptability to laboratory environments. This application note examines the essential practical considerations for cultivating and maintaining key model organisms used in ecotoxicity testing, providing detailed protocols and comparative analyses to guide researchers in organism selection. Within regulatory ecotoxicology, standardized tests using specific organisms provide data for chemical risk assessments conducted by agencies worldwide, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) [1]. The practical traits of these organisms—their culture requirements, life cycle characteristics, and overall ease of use—directly impact the reliability, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness of the toxicity data generated, which in turn influences regulatory decisions [6] [5].

Essential Practical Criteria for Test Organism Selection

When establishing a testing program, researchers must evaluate multiple practical dimensions of potential test organisms. The U.S. EPA and other regulatory bodies emphasize the importance of using test organisms chosen for their "availability, adaptability to laboratory testing, potential to be tested at different life stages, low-cost of maintenance, [and] historical data" [1]. These criteria ensure that laboratories can consistently produce high-quality, reliable data that meets regulatory standards for evaluating potential pesticide effects on non-target organisms [6].

Beyond these fundamental practicalities, a data-driven approach to organism selection is increasingly valuable. While historical precedent often guides choices, leveraging genomic data, protein structure, and evolutionary context can help identify organisms with high biological relevance to specific research problems, potentially leading to more predictive toxicity models [23]. Furthermore, proper reporting of all methodological details—from test design to exposure conditions and statistical analysis—is crucial for regulatory acceptance of the resulting data [5].

Comparative Analysis of Standard Test Organisms

The following section provides a detailed comparison of commonly used test organisms, with quantitative data summarized for direct comparison of their key practical traits.

Table 1: Comparative Practical Traits of Standard Aquatic Test Organisms

| Organism | Optimal Culture Temperature (°C) | Life Cycle Duration | Ease of Culture | Space Requirements | Regulatory Testing Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daphnia magna | 20 ± 1 | ~7-10 days (first brood) | Moderate | Low | Acute and chronic toxicity testing; EPA TEG 850.1010 / OECD 202 |

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | 12 ± 2 | 2-3 years to maturity | Difficult | High | Acute toxicity testing; EPA TEG 850.1075 / OECD 203 |

| Fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) | 25 ± 1 | 3-4 months to maturity | Moderate | Moderate | Acute and chronic toxicity, including larval survival and growth; EPA TEG 850.1075 / OECD 210 |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | 28.5 ± 1 | 3-4 months to maturity | Moderate | Moderate | Developmental toxicity, endocrine disruption; OECD 236 |

| Green alga (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) | 22 ± 2 | ~8-10 hours (doubling time) | Easy | Very Low | Growth inhibition testing; OECD 201 |

Table 2: Laboratory Infrastructure Demands for Test Organism Maintenance

| Organism Type | Feeding Requirements | Water Quality Monitoring | Specialized Equipment | Personnel Time Commitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microalgae | Simple nutrient solutions | Moderate (pH, nutrients) | Incubator/shaker, spectrophotometer | Low (minutes daily) |

| Invertebrates (Daphnia) | Live algae (e.g., Chlorella) | High (DO, pH, hardness) | Dissolved oxygen meter, water filtration | Moderate (hours weekly) |

| Small Fish Species | Commercial flakes, live/frozen food | Very High (ammonia, nitrite, nitrate) | Recirculating systems, biofilters, aeration | High (daily feeding, system checks) |

Detailed Culture Protocols

Daphnia magna Culturing Protocol

Principle: Daphnia magna (water flea) is a cornerstone freshwater crustacean in ecotoxicology, used for assessing chemical effects on survival, reproduction, and behavior in aquatic invertebrates.

Materials:

- Culture Vessels: Glass aquaria or food-grade plastic containers (2-10L)

- Culture Medium: Reconstituted moderately hard water (EPA recipe: 192 mg/L NaHCO₃, 120 mg/L CaSO₄·2H₂O, 120 mg/L MgSO₄, 8 mg/L KCl)

- Food Source: Freshly cultured green algae (Chlorella vulgaris or Selenastrum capricornutum) at 100,000-300,000 cells/mL/day, supplemented with yeast

- Environmental Control: Temperature-controlled chamber (20 ± 1°C), 16:8 hour light:dark cycle

- Aeration: Gentle air supply without creating water currents

Procedure:

- Water Preparation: Prepare reconstituted water 24 hours before use and aerate to stabilize pH and oxygenate.

- Inoculation: Transfer 20-50 adult daphnids per liter of culture medium.

- Daily Maintenance: Feed algae suspension daily; monitor water quality parameters (pH 7.0-8.5, dissolved oxygen >6 mg/L).

- Harvesting: For toxicity tests, collect neonates (<24 hours old) using a wide-bore pipette to avoid damage.

- Culture Renewal: Replace 50-80% of culture medium twice weekly to maintain water quality and remove waste.

Quality Control:

- Maintain brood sizes >6 neonates per adult under control conditions

- Keep control mortality <20% in chronic tests

- Document culture health and reproduction data regularly

RTgill-W1 Cell Line Maintenance Protocol

Principle: The RTgill-W1 cell line, derived from rainbow trout gill epithelium, represents a New Approach Methodology (NAM) that can reduce or replace fish in acute toxicity testing [24] [25].

Materials:

- Cell Line: RTgill-W1 (ATCC or equivalent source)

- Culture Medium: Leibovitz's L-15 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin

- Culture Vessels: T-75 flasks for maintenance; 96-well plates for toxicity testing

- Incubation: Non-humidified incubator at 19-21°C (ambient CO₂)

Procedure:

- Subculturing:

- Remove spent medium and rinse cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Add trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) and incubate until cells detach (5-10 minutes)

- Neutralize trypsin with complete medium and centrifuge at 200 × g for 5 minutes

- Resuspend pellet in fresh medium and seed at 1:3 to 1:5 split ratio

- Feeding: Replace medium every 2-3 days

- Cryopreservation:

- Suspend cells in complete medium with 10% DMSO at 1-5 × 10ⶠcells/mL

- Freeze at -1°C/minute to -80°C before transferring to liquid nitrogen

Applications:

- Miniaturized OECD Test Guideline 249: Fish cell line acute toxicity [24]

- Cell Painting assay for high-throughput phenotypic screening [25]

- Mechanism-based toxicity assessment using transcriptomics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Ecotoxicity Testing

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstituted Freshwater | Standardized aqueous medium for aquatic tests | EPA recipes available for different hardness levels; essential for test reproducibility |

| L-15 Medium with FBS | Culture medium for piscine cell lines | Supports RTgill-W1 growth without COâ‚‚ control; serum lot selection critical for consistency |

| Algal Food Suspension | Nutrition for daphnid cultures | Chlorella vulgaris at 3-5 × 10ⶠcells/mL; quality affects daphnid health and reproduction |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Vehicle for poorly soluble test chemicals | Keep final concentration ≤0.1% to avoid solvent toxicity; include solvent controls |

| Cell Viability Assays | Assessment of cytotoxic effects | AlamarBlue, MTT, or CFDA-AM for fish cells; neutral red uptake for daphnid cells |

| In Vitro Disposition Model | Predicts freely dissolved chemical concentrations | Corrects for chemical sorption in vitro; improves in vitro-in vivo extrapolation [24] |

| FK-3000 | FK-3000|6,7-di-O-acetylsinococuline|For Research | FK-3000 is a plant-derived compound for cancer research, inhibiting NF-κB/COX-2. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Glucopiericidin B | Glucopiericidin B, CAS:108073-61-6, MF:C31H47NO9, MW:577.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflows

Integrated Testing Strategy Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a modern, integrated approach to ecotoxicity testing that combines in silico, in vitro, and in vivo elements:

This workflow emphasizes how preliminary in silico and in vitro approaches can prioritize chemicals for targeted in vivo testing, reducing animal use while maintaining regulatory relevance [1] [24].

Organism Selection Decision Framework

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach for selecting appropriate test organisms based on research objectives and practical constraints:

This decision framework highlights the importance of considering both regulatory context and practical laboratory constraints when selecting test organisms, moving beyond traditional selection based solely on historical precedent [23] [1].

Regulatory Considerations and Method Validation

For regulatory acceptance, ecotoxicity studies must demonstrate reliability through standardized evaluation criteria. The CRED (Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data) framework provides 20 reliability and 13 relevance criteria for assessing aquatic ecotoxicity studies [5]. Similarly, the U.S. EPA has established specific evaluation guidelines for ecological toxicity data from open literature, which include minimum acceptance criteria such as explicit exposure duration, concurrent chemical concentration measurements, and comparison to appropriate controls [6].

Regulatory agencies are increasingly accepting NAMs that demonstrate sufficient predictivity of in vivo outcomes. For example, the combination of in vitro fish cell assays with in silico modeling has shown promising concordance with traditional fish acute toxicity tests, with 59% of adjusted in vitro phenotype altering concentrations (PACs) falling within one order of magnitude of in vivo lethal concentrations [24] [25]. This represents a significant advancement toward reducing animal use in ecotoxicity testing while maintaining scientific rigor.

The practical laboratory traits of test organisms—their culture requirements, life cycle characteristics, and ease of use—fundamentally shape ecotoxicity testing programs. As the field evolves toward more efficient, human-relevant, and ethical testing strategies, the integration of traditional whole-organism approaches with innovative in silico and in vitro methods represents the future of regulatory ecotoxicology. By carefully considering the practical aspects of organism selection and culture detailed in this application note, researchers can establish robust, reproducible testing systems that generate high-quality data for environmental decision-making while optimizing resource utilization.

Interspecies Variability and the Need for Diverse Test Species

Interspecies variability presents a fundamental challenge in toxicology and drug development, where data from model organisms must be extrapolated to humans. Traditional risk assessment has relied on default 10-fold safety factors to account for uncertainties in inter-species and inter-individual extrapolation [26]. However, these default assumptions are increasingly recognized as insufficient for capturing the complex toxicodynamic differences across species [27]. The emergence of novel experimental models now enables quantitative characterization of this variability, moving risk assessment away from heuristic approaches toward evidence-based, chemical-specific adjustment factors [28]. This application note details experimental strategies for characterizing interspecies variability, with specific protocols for using primary dermal fibroblasts from diverse species to inform chemical safety decisions.

The Scientific Basis for Diverse Species Testing

Historical Context and Current Limitations

For over 70 years, chemical risk assessment has employed default uncertainty factors to address interspecies differences. The original 100-fold safety factor was subdivided into two 10-fold factors accounting for inter-species and inter-individual variability [26]. Regulatory agencies further divided these into toxicokinetic and toxicodynamic components, with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency using a factor of 3.16 (10^0.5) for interspecies toxicodynamic differences [27]. However, authoritative bodies disagree on the appropriate values, and these defaults often lack chemical-specific justification [27].

The fundamental problem lies in the genetic uniformity of traditional rodent models used in regulatory toxicology. Inbred strains and F1 hybrids provide phenotypic uniformity but risk drawing conclusions from "outlier" strains not representative of heterogeneous populations [26] [28]. This limitation jeopardizes the translation of animal data to human health protection.

Evidence for Species-Specific Toxicodynamic Differences

Recent systematic analyses demonstrate substantial interspecies differences in biological responses. A review of 484 eyeblink conditioning experiments across ten species revealed consistent interspecies differences in acquisition rates, timing parameters, and stimulus protocols, challenging assumptions of mechanistic equivalence [29]. In toxicology, studies using primary dermal fibroblasts from 54 diverse species showed that both inter-species and inter-individual components contribute to sensitivity to cell death, with the magnitude of differences being chemical-dependent [27].

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of Interspecies Variability in Biological Systems

| Experimental System | Number of Species | Key Variability Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eyeblink conditioning | 10 | Consistent differences in acquisition rates and timing parameters | [29] |

| Cytotoxicity screening | 54 | Chemical-dependent variability in sensitivity to cell death | [27] |

| Dermal fibroblast stress resistance | 58 | Longer-lived species show greater resistance to chemical stressors | [27] |

Experimental Models for Assessing Interspecies Variability

In Vitro Models Using Primary Cells

Primary dermal fibroblasts have emerged as a valuable model for interspecies comparisons because they can be procured from a large number of animals and individuals and maintain species-specific characteristics in culture [27]. These cells retain differences in longevity across mammals, preserved at the level of global gene expression and metabolite concentrations [27]. Studies using fibroblasts from up to 58 mammalian and avian species demonstrated that cells from longer-lived species are more resistant to various chemicals and stress conditions [27].

The experimental workflow for utilizing this model involves:

In Vivo Population-Based Models

Genetically diverse mouse models have been developed to better characterize population variability. The Diversity Outbred and Collaborative Cross populations derive from common genetically heterogeneous ancestor strains, providing a toolbox for quantitative characterization of variability in drug and chemical effects [26] [28]. These models allow researchers to examine genetic contributions to susceptibility while controlling environmental factors, bridging the gap between inbred strains and human population diversity.

Protocol: Interspecies Cytotoxicity Screening Using Primary Dermal Fibroblasts

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Interspecies Fibroblast Cytotoxicity Screening

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Example Sources/Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture | Primary dermal fibroblasts from 54+ species | Interspecies variability assessment | Various species-specific sources |

| DMEM, MEM Alpha, FBS, L-glutamine | Cell culture maintenance | Fisher Scientific, MilliporeSigma | |

| Fibroblast Basal Medium, Growth Kit | Low-serum culture conditions | ATCC | |

| Chemical Library | 40 test compounds | Cytotoxicity screening | MilliporeSigma, Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Drugs, environmental pollutants, food/flavor agents | Representative chemical classes | Supplemental Table 1 [27] | |

| Assay Components | Cell Titer-Glo Luminescent Assay | Cell viability quantification | Promega |

| Tissue culture-treated 384-well microplates | High-throughput screening | Corning | |

| Tetraoctylammonium bromide, H2O2 | Control compounds | MilliporeSigma, Fisher Scientific |

Detailed Methodology

Cell Sourcing and Culture Conditions

Primary dermal fibroblasts should be obtained from a taxonomically diverse set of species. The published protocol utilized cells from 68 individuals representing 54 species, including humans, typical preclinical species, and representatives from other orders of mammals and birds [27]. Cells are maintained in appropriate media formulations (DMEM, MEM Alpha, or Fibroblast Basal Medium) supplemented with fetal bovine serum and growth factors according to species requirements. All cells are cultured under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) and used at low passages to maintain phenotypic stability.

Chemical Preparation and Plate Design

A diverse chemical panel is essential for comprehensive variability assessment. The protocol employs 40 chemicals including:

- Antineoplastic and other pharmaceutical compounds

- Environmental pollutants (flame retardants, pesticides)

- Food, flavor, and fragrance agents

Chemicals are selected based on three criteria:

- Compounds with in vivo toxicity values in multiple preclinical species

- Agents with reverse toxicokinetics data for in vitro-to-in vivo comparison

- Compounds with existing in vitro cytotoxicity data

Stock solutions are prepared in DMSO and stored at -80°C. For screening, compounds are serially diluted in 384-well deep-well plates using appropriate buffers.

Concentration-Response Screening

Cells are seeded in tissue culture-treated 384-well microplates at optimized densities for each species. After 24-hour attachment, cells are exposed to chemical concentrations in duplicate or triplicate, including vehicle controls. Plates are incubated for 24-72 hours based on the doubling time of each cell type. Cell viability is quantified using the Cell Titer-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay, which measures ATP content as a surrogate for metabolically active cells.

Data Analysis and Variability Quantification

Data analysis involves normalizing raw luminescence values to vehicle controls (100% viability) and positive cytotoxicity controls (0% viability). Concentration-response curves are fitted using four-parameter logistic models to derive AC50 values (concentration causing 50% activity reduction). Variability components are partitioned using mixed-effects models that account for both inter-species and inter-individual variability.

Table 3: Quantitative Outputs from Interspecies Cytotoxicity Screening

| Output Metric | Description | Application in Risk Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| AC50 Values | Concentration causing 50% cytotoxicity for each chemical-species combination | Basis for comparing relative sensitivity across species |

| Inter-species Variability Factor | Ratio of most to least sensitive species for a given chemical | Direct comparison to default factors of 3.16 or 2.5 |

| Intra-species Variability Factor | Ratio of most to least sensitive individual within a species | Informs default 3.16 factor for human variability |

| Chemical-specific Adjustment Factor | Experimentally-derived alternative to default factors | Replaces default assumptions with data-driven values |

Application in Risk Assessment

The experimental data generated through this protocol directly addresses key uncertainties in chemical risk assessment. Concentration-response cytotoxicity data from diverse species enables derivation of chemical-specific adjustment factors to replace default assumptions [27]. For some chemicals, the observed inter-species variability exceeds default factors, while for others it may be lower, enabling more precise risk characterization.

This approach contributes to the paradigm shift in risk assessment from reliance on in vivo toxicity testing toward higher-throughput in vitro methods [27]. The strategy extends beyond replacing animal tests to specifically addressing toxicodynamic interspecies variability, a longstanding data gap in chemical safety evaluation.

Characterizing interspecies variability is essential for robust chemical risk assessment and drug development. The protocol described here for interspecies cytotoxicity screening using primary dermal fibroblasts provides a practical approach to generate chemical-specific data on toxicodynamic differences. This experimental strategy, combined with emerging population-based in vivo models, enables moving beyond default uncertainty factors toward evidence-based safety decisions. As the field advances, integration of such approaches into regulatory frameworks will enhance the scientific basis of chemical risk assessment while potentially reducing animal use through targeted, mechanistically-informed testing strategies.

From Theory to Bench: Building Your Ecotoxicity Test Battery

Standardized test guidelines are foundational tools for assessing the potential effects of chemicals on human health and the environment. These guidelines provide internationally recognized methodologies that ensure testing is conducted consistently, reliably, and efficiently across different laboratories and regulatory jurisdictions. For researchers investigating ecotoxicity test organism selection criteria, understanding these standardized frameworks is essential for designing scientifically valid and regulatory-relevant studies. The development and maintenance of these guidelines involve collaborative efforts from regulatory agencies, academia, industry, and environmental organizations worldwide, ensuring they reflect state-of-the-art science while addressing evolving regulatory needs [2].

The importance of these standardized approaches extends beyond methodological consistency. They form the basis for the Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) system, which enables test data generated in one country to be accepted for regulatory purposes in another, thereby reducing redundant testing and facilitating international cooperation in chemical safety assessment [2]. For ecotoxicity researchers, this international harmonization is particularly valuable when selecting test organisms, as it provides clear frameworks for determining which species and testing approaches will yield regulatory-accepted results across multiple jurisdictions.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

The OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals represent a comprehensive collection of internationally recognized methods for chemical safety assessment. These guidelines are uniquely positioned as globally accepted standards for non-clinical environmental and health safety testing of chemicals and chemical products, including industrial chemicals, pesticides, and personal care products [2]. The OECD guidelines are systematically organized into five thematic sections: Physical Chemical Properties (Section 1), Effects on Biotic Systems (Section 2), Environmental Fate and Behaviour (Section 3), Health Effects (Section 4), and Other Test Guidelines (Section 5) [2]. This structured approach enables researchers to locate appropriate testing methodologies for specific assessment endpoints relevant to their ecotoxicity organism selection research.

The OECD guidelines undergo continuous expansion and updating to reflect scientific progress. Recent updates in 2025 have introduced new approaches for omics analysis, defined approaches for surfactant chemicals, and revisions to incorporate the latest advancements in alternative methods that reduce reliance on animal testing through the application of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) Principles [2]. For ecotoxicity researchers, these updates signify the evolving nature of test organism selection criteria, with increasing emphasis on mechanistic understanding and alternative testing approaches that may complement or supplement traditional whole-organism testing.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

The EPA's Test Guidelines for Pesticides and Toxic Substances provide the methodological foundation for generating data submitted to support regulatory decisions under key US statutes, including the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA), and the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) [30] [31]. These guidelines are developed through a collaborative process involving EPA scientists and external experts from the scientific community, industry, non-profit organizations, and other governmental bodies [31]. The EPA engages in extensive harmonization activities with the OECD to align its testing approaches with international standards, reducing testing burdens while promoting scientific consistency [31].

A significant aspect of EPA's guideline development is its active participation in the Interagency Coordinating Committee for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM), which focuses on developing and validating toxicology test methods that reduce, refine, or replace animal use while maintaining scientific rigor [31]. For ecotoxicity researchers, this emphasis on alternative methods influences test organism selection by encouraging consideration of non-whole animal approaches and lower trophic level species that can provide predictive data for higher organisms. The EPA's Health Effects Test Guidelines (Series 870) encompass comprehensive testing approaches for acute toxicity, subchronic toxicity, chronic toxicity, genetic toxicity, neurotoxicity, and specialized endpoints [32], providing a structured framework for determining appropriate test organisms based on specific assessment goals.

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) develops internationally agreed standards that represent distilled wisdom from global experts representing manufacturers, sellers, buyers, customers, trade associations, users, and regulators [33]. While ISO standards cover a vast range of activities beyond chemical testing, they include relevant standards for quality management, environmental management, health and safety, and specific laboratory methodologies that support ecotoxicity testing [33] [34]. ISO standards are developed through a consensus-driven process that ensures global relevance and applicability across different regulatory and technical contexts.

For ecotoxicity researchers, ISO standards provide supporting frameworks for laboratory quality assurance, environmental monitoring, and specific testing methodologies that complement the substance-specific testing guidelines provided by OECD and EPA. The most widely implemented ISO standards include ISO 9001 for quality management systems, ISO/IEC 27001 for information security, and ISO 14001 for environmental management systems [34]. These management standards establish foundational requirements for laboratory operations and data integrity that indirectly influence test organism selection by ensuring consistency in test system maintenance, environmental control, and data documentation practices.

ASTM International

ASTM International develops technical standards for materials, products, systems, and services, including extensive laboratory testing standards that specify standard dimensions, design, and manufacturing requirements for laboratory equipment and instruments [35]. With over 13,000 global standards developed through the work of more than 35,000 technical members worldwide, ASTM standards provide critical specifications that ensure experimental consistency and apparatus interoperability across different testing facilities [36]. While ASTM standards typically focus more on equipment and general testing approaches rather than chemical-specific testing protocols, they nevertheless provide important foundational support for ecotoxicity testing programs.

For researchers focused on ecotoxicity test organism selection, ASTM standards offer guidance on appropriate laboratory apparatus, test system design, and quality control measures that support the implementation of OECD and EPA testing guidelines. The organization's commitment to serving global societal needs through standards that positively impact public health and safety aligns with the overarching goals of chemical safety assessment [36]. ASTM's proficiency testing programs and certified reference materials further support method validation and quality assurance in ecotoxicity testing laboratories [36].