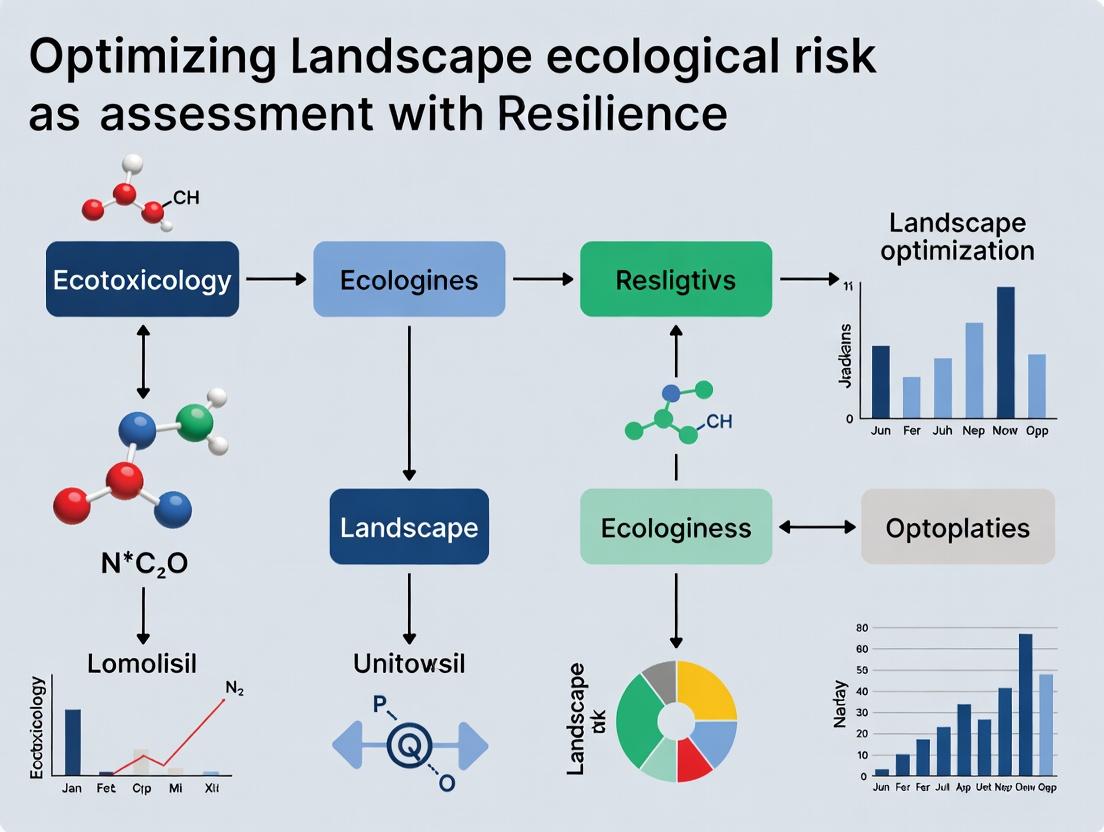

Optimizing Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment with Resilience: A Framework for Scientific Management and Sustainable Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for integrating ecosystem resilience into landscape ecological risk assessment (LERA) to enhance the scientific management of ecological resources.

Optimizing Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment with Resilience: A Framework for Scientific Management and Sustainable Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for integrating ecosystem resilience into landscape ecological risk assessment (LERA) to enhance the scientific management of ecological resources. It begins by exploring the foundational concepts and limitations of traditional LER models, highlighting the shift towards incorporating ecosystem services and resilience theory. The core of the article details methodological advancements, including the integration of a 'Resistance-Adaptation-Recovery' resilience framework with a 'Disturbance-Vulnerability-Loss' risk model, alongside spatial analysis tools like bivariate Moran's Index and Geodetector. It addresses critical challenges such as spatial scale optimization, subjective parameterization, and multi-scale analysis. The validation section explores comparative assessment through ecological management zoning and coupling coordination analysis, offering insights for targeted interventions. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and environmental management professionals, this synthesis aims to bridge theory and practice, providing actionable insights for reducing regional ecological risks and promoting ecosystem sustainability.

Foundations and Limitations: From Static Landscape Patterns to Dynamic Ecosystem Resilience

The discipline of ecological risk assessment (ERA) originated not from an ecological foundation, but from a human-centric one. Its roots are firmly planted in the 1970s-1980s with frameworks designed to evaluate cancer risks and other human health impacts from chemical exposures [1]. The initial focus was on single chemical stressors and their effects on individual organisms, primarily humans [1]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) early guidelines solidified this chemical-by-chemical, health-focused approach [2] [3].

A pivotal expansion began in the early 1990s, as recognition grew that ecosystems themselves were endpoints of value requiring protection. The EPA's Framework for Ecological Risk Assessment (1992) and subsequent guidelines (1998) formally established a parallel process for ecological systems [2] [1]. This era marked the shift from "human health in the environment" to "health of the environment." However, these assessments often remained limited in scale, focusing on specific sites (e.g., a contaminated field) and a narrow suite of stressors [1].

The 21st century has driven the field toward greater complexity and scale. Key limitations of traditional ERA became apparent: an inability to handle multiple interacting stressors, spatial and temporal dynamics, and landscape-level processes [1]. In response, Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment (LERA) emerged as a dominant paradigm. LERA evaluates the possible adverse effects of human activities or natural hazards on the compositions, structures, functions, and processes of a landscape [4]. It leverages landscape pattern indices derived from land use/cover change (LUCC) data to act as integrative proxies for the cumulative impact of multiple stressors—from pollution and urbanization to climate change and invasive species [5] [6]. This allows for the assessment of regional, watershed, and even continental-scale risks, moving far beyond the single-site assessments of the past [2] [4].

The most recent evolution integrates concepts of resilience and ecosystem services directly into the risk calculus. This optimizes LERA by not just diagnosing risk but also evaluating the system's inherent capacity to resist and recover, thereby guiding more nuanced ecological management and zoning [7] [8]. This progression—from human toxicology to landscape ecology to resilience-informed management—frames the modern toolkit for understanding and mitigating ecological risk in an increasingly human-modified world.

Foundational Frameworks and Current Methodological Approaches

Modern ecological risk assessment employs a spectrum of frameworks, from the traditional EPA process to advanced landscape-level models. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and applications of the predominant approaches.

Table 1: Core Methodological Frameworks in Ecological Risk Assessment

| Framework Name | Spatial Scale & Primary Focus | Key Stressors Assessed | Typical Application Context | Key References & Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional EPA Ecological Risk Assessment | Local to site-specific. Focus on specific receptors (species, populations). | Primarily chemical contaminants (e.g., pesticides, heavy metals). | Regulatory decision-making for chemical registration, contaminated site remediation. | EPA Guidelines (1998); Technical focus on exposure characterization [3]. |

| Cumulative Risk Assessment (CRA) | Expands to regional scales. Emphasizes combined effects. | Multiple chemical and non-chemical stressors (e.g., pollution, habitat loss, climate). | Evaluating complex environmental impacts where stressors interact. | EPA planning documents; Stressor-based and Relative Risk Model (RRM) approaches [1]. |

| Landscape Ecological Risk (LER) Assessment | Watershed, regional, national. Focus on landscape patterns and processes. | Integrated proxy via Land Use/Cover Change (LUCC). Captures compound effects of urbanization, agriculture, fragmentation, etc. | Regional planning, ecosystem health monitoring, spatial zoning for conservation/restoration. | Predominant in contemporary research [9] [4] [5]. |

| Resilience-Integrated LER Assessment | Regional. Couples risk with recovery capacity. | LUCC, combined with metrics of ecosystem service provision and resilience. | Optimized ecological management zoning, identifying areas for adaptation, conservation, or restoration. | Emerging best-practice approach [7] [8]. |

The Landscape Pattern Index Method is the most widely applied LER approach. It uses a standard formula: LER = ∑ (Area of Landscape Type / Total Area) * Landscape Loss Index. The Loss Index itself combines a Landscape Disturbance Index (based on metrics like fragmentation) and a Landscape Vulnerability Index (a pre-assigned weight for each land use type, e.g., wetland > forest > cropland > built-up) [6]. This model's output is a spatially explicit risk map, revealing patterns such as "high in the northwest, low in the southeast" as found in the Fuchunjiang River Basin [4].

A significant advancement is the Two-Dimensional Matrix Model, which enriches the concept of "risk" by separately evaluating the probability of risk occurrence and the potential loss severity. Probability is modeled using factors like topographic sensitivity and ecological resilience, while loss is modeled as the degradation degree of key ecosystem services (e.g., water retention, carbon sequestration) [8]. This matrix creates a more nuanced risk classification than a single index.

The cutting edge is the Integration of Resilience. Here, LER assessment is coupled with a parallel evaluation of Ecosystem Resilience (ER), often based on the capacity, adaptability, and transformability of ecosystem services. Spatial correlation analysis (e.g., bivariate Moran's I) between LER and ER allows for functional zoning: Ecological Conservation (Low Risk, High Resilience), Ecological Restoration (High Risk, Low Resilience), and Ecological Adaptation (intermediate states) [7]. This directly supports the thesis of optimizing assessment with resilience research.

Application Notes and Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment via the Landscape Pattern Index Method

This protocol details the standard workflow for generating a spatially explicit LER index using remote sensing data, as applied in studies of major river basins [9] [4].

1. Problem Formulation & Study Area Demarcation

- Objective: To assess the spatiotemporal evolution of landscape ecological risk and its driving forces.

- Spatial Unit Definition: Define the study area (e.g., watershed, administrative region). Determine the optimal analysis scale (grain and extent). Research indicates the analytical effect is often optimal at a specific scale (e.g., 90 km² grids for the Yellow River Basin) [9]. Use the coefficient of variation method to find the scale where landscape indices stabilize.

2. Data Acquisition & Preprocessing

- Core Data: Acquire multi-temporal Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) raster data (e.g., for years 1990, 2000, 2010, 2020) at 30m resolution from sources like USGS or ESA.

- Ancillary Data: Collect vector boundaries, digital elevation models (DEM), and socioeconomic data (GDP, population) for driving force analysis.

- Preprocessing: Re-project all data to a unified coordinate system. Reclassify LULC data into standard classes (e.g., Cropland, Forest, Grassland, Waterbody, Built-up, Unused Land).

3. Landscape Index Calculation & Risk Model Construction

- Grid Division: Overlay a vector grid (e.g., 3km x 3km) onto the study area. This grid becomes the assessment unit [6].

- Index Computation: For each assessment unit and time period, use Fragstats software to calculate:

- Percentage of Landscape (PLAND) for each LULC class.

- Patch Density (PD), Edge Density (ED), and Landscape Division Index (DIVISION).

- Construct Loss Index: For each LULC class i in grid k:

- Calculate Landscape Disturbance Index (LDIki). A common model is:

LDI = a*DIVISION + b*PD + c*ED(where a, b, c are weights summing to 1) [6]. - Assign a Landscape Vulnerability Index (LVIi) on a ordinal scale (e.g., 1-6) based on ecosystem stability and sensitivity. For example: Unused Land (1), Built-up (2), Cropland (3), Grassland (4), Waterbody (5), Forest (6).

- Compute Landscape Loss Index:

LLI*ki* = LDI*ki* * LVI*i*.

- Calculate Landscape Disturbance Index (LDIki). A common model is:

- Compute Final LER Index: For each grid k,

LER*k* = ∑ (A*ki* / A*k*) * LLI*ki*, where A is area.

4. Spatial Analysis & Driving Force Detection

- Spatial Statistics: Calculate Global and Local Moran's I to evaluate spatial autocorrelation and identify High-High or Low-Low risk clusters [5].

- Geodetector Analysis: Use the Geodetector model (Factor Detector, Interaction Detector) to quantify the explanatory power (q-statistic) of natural (elevation, slope, precipitation) and anthropogenic (GDP, population density, distance to roads) factors on the spatial heterogeneity of LER [4] [5].

Protocol: Multi-Scenario Simulation of Future Landscape Ecological Risk

This protocol uses land use simulation models to project future LER under different policy scenarios, essential for proactive management [5] [6].

1. Historical Change Analysis & Driver Selection

- Analyze historical LULC transition matrices (2000-2020) to identify major conversion pathways (e.g., cropland to urban land).

- Select driving factors for simulation: Elevation, Slope, Distance to Rivers/Roads/Urban Centers, Population Density, GDP. Standardize all factor rasters.

2. Land Use Simulation Using the PLUS Model

- Training: Use the Land Expansion Analysis Strategy (LEAS) module in the PLUS model to extract land use expansion between two historical periods and identify contributions of each driver using a Random Forest algorithm.

- Scenario Development: Define and parameterize scenarios for 2030/2050:

- Natural Development (NDS): Trends continue based on historical transition probabilities.

- Economic Development (EDS): Increase probability of cropland/forest converting to built-up land; restrict ecological land growth.

- Ecological Protection (EPS): Restrict conversion of ecological lands (forest, grassland, water); encourage conversion of cropland to ecological uses.

- Cropland Protection (CPS): Strictly protect cropland from conversion; urban expansion is limited to low-quality land.

- Simulation: Use the CARS module with a Multi-type Random Patch Seed mechanism to generate future LULC maps under each scenario.

3. Future LER Assessment & Scenario Comparison

- Apply the LER index model (Protocol 3.1) to the simulated future LULC maps.

- Compare the area, spatial distribution, and statistical characteristics of different risk levels across scenarios. The Ecological Protection and Cropland Protection scenarios typically show lower future LER compared to development-focused scenarios [6].

Protocol: Resilience-Informed Ecological Risk Assessment and Zoning

This advanced protocol integrates ecosystem services and resilience to move from risk assessment to management zoning [7] [8].

1. Two-Dimensional Risk Assessment

- Probability (P) Layer: Construct a composite index representing the likelihood of ecosystem degradation. Common indicators include:

- Landscape Vulnerability: As calculated in Protocol 3.1.

- Topographic Sensitivity: Based on slope and relief amplitude.

- Ecological Resilience: An index from vegetation biomass (NDVI), biodiversity, and landscape connectivity metrics.

- Loss (L) Layer: Model potential loss as the degradation of key ecosystem services. Use the InVEST model or equivalent to quantify:

- Service supply for a baseline and stressed condition (e.g., water yield under extreme rainfall, soil retention under high erosion).

- Calculate degradation degree:

Loss = (Supply*baseline* - Supply*stressed*) / Supply*baseline*.

- Risk Matrix: Classify P and L into levels (e.g., Low, Medium, High). Cross-tabulate to create a 3x3 risk matrix, where final risk level is determined by the combination (e.g., High P + High L = Highest Risk).

2. Ecosystem Resilience (ER) Assessment

- Construct a separate ER Index focusing on adaptive capacity. Indicators include:

- Ecosystem Service Capacity: Total magnitude of key services.

- Diversity/Redundancy: Land use diversity index, habitat quality patch diversity.

- Adaptive Potential: Measured as the distance to natural ecological sources or conservation areas.

3. Bivariate Spatial Zoning

- Perform a bivariate local spatial autocorrelation analysis between the final LER index and the ER index.

- Interpret the clusters to define management zones:

- Ecological Conservation Zone: Low LER - High ER. Strategy: Maintain current protection, limit human disturbance.

- Ecological Restoration Zone: High LER - Low ER. Strategy: Prioritize for restoration projects (afforestation, wetland rehabilitation).

- Ecological Adaptation Zone: High LER - High ER OR Low LER - Low ER. Strategy: Adaptive management; monitor for changes, enhance connectivity.

- Ecological Monitoring Zone: Low LER - Low ER. Strategy: Monitor for potential degradation.

Evolution of Ecological Risk Assessment Frameworks and Methods

Spatial Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment Workflow

Resilience-Integrated LER Assessment and Management Zoning Model

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions and Analytical Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Item/Software | Primary Function in LERA | Critical Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Spatial Data | Multi-temporal Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Raster Datasets (e.g., USGS NLCD, ESA CCI-LC) | The fundamental input for calculating landscape pattern indices and tracking change. | Resolution & consistency across time periods is critical. 30m resolution is common; higher resolution increases computational load. |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | ArcGIS Pro, QGIS, GDAL/Python Libraries (geopandas, rasterio) | Platform for data management, preprocessing, spatial analysis, grid creation, and final map production. | Proficiency in raster algebra, zonal statistics, and projection management is essential. |

| Landscape Metric Analysis | FRAGSTATS (standalone or library) | The industry-standard software for computing a wide array of landscape pattern indices (patch, class, landscape level). | Careful selection of relevant metrics (e.g., Edge Density, Patch Density, Landscape Division Index) based on the study's ecological questions. |

| Statistical & Spatial Analysis | R (with spdep, GD, sf packages), GeoDa, MATLAB |

Performing advanced statistics: spatial autocorrelation (Moran's I), Geodetector analysis, regression modeling, and cluster analysis. | Geodetector (GD) model is particularly powerful for quantifying factor contributions to spatial heterogeneity of LER [4] [5]. |

| Ecosystem Service Modeling | InVEST Suite (Natural Capital Project), ARIES | Quantifying and mapping ecosystem service supply (e.g., water purification, carbon storage, habitat quality) for loss assessment and resilience metrics. | Model outputs require local calibration and validation with field data where possible to improve accuracy. |

| Land Use Change Simulation | PLUS Model, CLUE-S, FUTURES | Projecting future land use scenarios under different socio-economic and policy pathways. | PLUS model is increasingly favored for its patch-generation simulation and ability to integrate driving factors via Random Forest [5] [6]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources | Cluster/Cloud computing access (e.g., Google Earth Engine, local HPC) | Handling large raster datasets, running iterative simulations (like Monte Carlo in RRM), and processing regional/continental scale analyses. | Essential for large-scale or high-resolution studies to achieve feasible processing times. |

| 2-ethylpentanedioyl-CoA | 2-ethylpentanedioyl-CoA, MF:C28H46N7O19P3S, MW:909.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 6-OAc PtdGlc(di-acyl Chain) | 6-OAc PtdGlc(di-acyl Chain), MF:C49H92NaO14P, MW:959.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Discussion and Future Directions

The evolution from human health-centric chemical assessments to integrated landscape-resilience models represents a paradigm shift in how science characterizes environmental risk. The optimization of LERA with resilience research directly addresses the core thesis, moving the field from descriptive risk mapping to prescriptive management planning. The bivariate zoning of LER and ER provides a scientifically defensible basis for prioritizing conservation resources, targeting restoration, and implementing adaptive management [7].

Key challenges remain. First, scale dependency is inherent; findings at a 90 km² grid scale may not hold at 1 km² [9]. Future work must explicitly address multi-scale analyses. Second, while landscape patterns are excellent proxies, validating predicted ecological risk against direct, on-the-ground measurements of biodiversity loss, soil erosion, or water quality decline is crucial for reinforcing model credibility. Third, the integration of dynamic global change drivers, particularly climate change, into scenario simulations needs refinement. Current models often treat climate as a static background factor rather than a dynamic, interactive stressor.

The future of ERA lies in greater mechanistic integration. This includes coupling LER models with process-based ecological models (e.g., species distribution models, hydrological models) and advancing towards a "digital twin" of landscapes. Furthermore, the development of standardized, open-source computational workflows will enhance reproducibility and allow for comparative risk assessments across continents, ultimately providing a robust scientific foundation for global biodiversity and sustainability goals.

Core Principles and Traditional Models of Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment

Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment (LERA) represents a critical evolution in ecological risk science, shifting focus from the impacts of single contaminants on specific receptors to a holistic analysis of how spatial patterns and multi-source stressors affect ecosystem integrity [4] [10]. This framework is founded on the principle that landscape structure—the composition, configuration, and connectivity of ecosystems—directly mediates ecological functions and their vulnerability to disturbances from human activities and environmental change [11]. The rapid global processes of urbanization, land-use transformation, and climate change have made LERA an indispensable tool for diagnosing environmental health, predicting potential ecological degradation, and informing sustainable land management policies [9] [12].

The genesis of LERA lies in traditional ecological risk assessment, which originated in toxicology and human health studies [4]. As ecological challenges grew in scale and complexity, the field expanded to consider regional, landscape-level risks. A landmark in this evolution was the development of the Relative Risk Model (RRM), which introduced a structured approach to evaluating multiple stressors across diverse habitats [10]. Concurrently, the integration of landscape ecology principles, facilitated by advances in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing, enabled researchers to quantify spatial heterogeneity and its ecological consequences [4] [10]. This fusion of risk science and spatial analysis forms the bedrock of contemporary LERA, which now seeks not only to assess static risk but also to integrate concepts of ecosystem resilience—the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and retain its function—to guide proactive ecological restoration and management [11].

Core Principles of Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment

The practice of LERA is governed by four interrelated core principles that ensure its scientific rigor and practical relevance.

Spatial Heterogeneity and Pattern-Process Interaction: This principle asserts that ecological risks are not uniformly distributed but are inherently spatial, shaped by the mosaic of landscape patches (e.g., forests, wetlands, urban areas). The spatial arrangement of these patches influences ecological processes like species dispersal, nutrient cycling, and disturbance propagation. A fragmented landscape, for instance, may exhibit higher ecological risk due to impaired connectivity and diminished habitat quality [9] [10]. Assessment must therefore capture metrics of landscape pattern, such as fragmentation, aggregation, and diversity, to understand risk drivers [9] [12].

Multi-Scale Analysis: Ecological processes and risks manifest at different scales. An effective LERA must identify the optimal scale of analysis. Studies demonstrate that analytical outcomes, such as the correlation between pattern and risk, are scale-dependent [9]. For example, research in the Yellow River Basin found that a 90 km × 90 km grid was the most effective scale for spatial analysis [9]. The principle requires a nested approach, considering broad-scale drivers (e.g., climate, economics) and fine-scale responses (e.g., local habitat loss).

Integration of Landscape Pattern and Ecosystem Function: Traditional models often rely solely on structural landscape indices. A leading-edge principle is coupling these patterns with functional metrics, particularly ecosystem services. Landscape vulnerability can be more objectively evaluated based on the provision of key services like water purification, carbon sequestration, and soil retention, rather than on subjective land-use classifications [11]. This integration provides a clearer ecological connotation to risk indices, linking structural changes directly to functional losses for human well-being [11].

Quantitative and Probabilistic Foundation: LERA is fundamentally a quantitative exercise. It employs mathematical models to convert landscape data into probabilistic estimates of risk [13]. This involves calculating indices of landscape disturbance and vulnerability, often followed by spatial statistics (e.g., geodetectors, Moran's I) to identify hotspots and driving forces [4] [12]. The quantitative principle ensures objectivity, repeatability, and the ability to forecast risks under different scenarios [13].

Traditional Assessment Models and Methodologies

Three primary conceptual models have historically shaped the methodology of LERA.

The Landscape Loss Model (Pattern-Based Model): This is the most widely applied traditional model. It calculates a Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI) by integrating a landscape disturbance index (based on metrics like fragmentation, dominance, and division) with a landscape vulnerability index (an a priori ranking of land-use/cover types) [12] [10]. The risk is computed within sampling grids across the study area, generating a continuous spatial surface of risk values. Its strength lies in its straightforward application using GIS and remote sensing data, making it suitable for assessing risks from composite, diffuse stressors like generalized land-use change [10].

The Relative Risk Model (RRM): This model adopts a risk source-stressor-habitat-receptor framework [10]. It involves identifying specific risk sources (e.g., industrial discharge, urban sprawl), the stressors they produce (e.g., toxins, habitat loss), and the habitats and ecological receptors (e.g., fish populations, bird communities) that are exposed. Experts rank and weight these components to model exposure and effect pathways. The RRM is powerful for sites with multiple, identifiable point-source and non-point-source risks, as it helps prioritize management actions for specific stressors [10].

The Pressure-State-Response (PSR) and Derived Frameworks: This causal model, rooted in systems thinking, organizes indicators into three categories: Pressure (human activities stressing the environment), State (the resulting condition of the landscape), and Response (societal actions taken to improve the state). LERA typically focuses on the Pressure and State components. For example, urban expansion (Pressure) leads to increased patch density and reduced connectivity (State), resulting in higher ecological risk [12]. This model is valuable for communicating the causes and consequences of risk to policymakers.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment Models

| Model | Core Concept | Typical Application Scale | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Loss Model [12] [10] | Risk as a function of landscape pattern deviation and inherent vulnerability. | Regional, watershed, landscape (100s – 1000s km²). | Simple, reproducible, excellent for spatial visualization and trend analysis with standard GIS data. | Weak linkage to specific ecological processes; vulnerability ranking can be subjective. |

| Relative Risk Model (RRM) [10] | Risk estimated through pathways linking sources, stressors, and valued receptors. | Local to regional, often for sites with defined multiple stressors (e.g., estuaries, industrial zones). | Explicitly models cause-effect pathways; effective for prioritizing specific management interventions. | Data-intensive; requires expert judgment for weighting, which can introduce subjectivity. |

| Pressure-State-Response (PSR) [12] | Organizes indicators within a causal framework of human impact, ecological condition, and management action. | Any scale, often used for regional environmental reporting and policy analysis. | Excellent communication tool; clearly links human activity to ecological outcome and management. | Does not provide a single, quantified risk index; more of an organizing framework than a calculative model. |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conducting a Baseline Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment Using the Landscape Loss Model

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for a pattern-based LERA, forming the basis for integration with resilience metrics [11] [12].

- Study Area Delineation and Scale Determination: Define the geographical boundary (e.g., watershed, administrative region). Conduct a scale sensitivity analysis by calculating landscape indices at multiple grid sizes (e.g., 1km, 2km, 5km). The optimal analysis scale is often identified where the coefficient of variation for key indices stabilizes [9].

- Data Acquisition and Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Classification: Acquire multi-temporal satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel). Classify images into LULC types (e.g., forest, cropland, urban, water) for each time point (e.g., 1990, 2000, 2010, 2020) using supervised classification in software like ENVI or ERDAS Imagine [9] [4].

- Landscape Pattern Analysis: Using Fragstats software, calculate landscape-level and class-level metrics for each sampling grid. Essential metrics include:

- Percentage of Landscape (PLAND): Measures composition.

- Patch Density (PD): Indicates fragmentation.

- Landscape Division Index (DIVISION): Reflects connectivity.

- Aggregation Index (AI): Measures patch clumpiness [12].

- Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI) Calculation:

- Compute the Disturbance Index (Ei) for each landscape type i:

Ei = aCi + bNi + cDi, whereCiis fragmentation,Niis disturbance,Diis division, and a, b, c are weights summing to 1 [12]. - Assign a Vulnerability Index (Vi). Traditionally, this is an ordinal ranking (e.g., 1-6) for each LULC type based on expert judgment [11].

- Calculate the Loss Index (Ri) for each landscape type:

Ri = Ei * Vi. - Compute LERI for each assessment grid k:

LERIk = Σ (Aki / Ak) * Ri, whereAkiis the area of landscape i in grid k, andAkis the total area of grid k [12].

- Compute the Disturbance Index (Ei) for each landscape type i:

- Spatial Interpolation and Risk Level Zoning: Use Kriging or IDW interpolation in GIS to create a continuous LERI surface. Apply natural breaks classification to define risk levels (e.g., lowest, lower, medium, higher, highest) [9] [10].

- Spatio-Temporal Change Analysis and Driver Identification: Analyze risk transitions between periods. Use the Geodetector model (q-statistic) or Random Forest regression to quantify the explanatory power of driving factors like GDP, population density, slope, and precipitation on the LERI spatial pattern [4] [12].

Landscape Loss Model Assessment Workflow

Protocol 2: Integrating Ecosystem Services and Resilience for an Optimized Assessment

This advanced protocol modifies the traditional model by refining the vulnerability index and coupling risk with resilience, aligning with the thesis focus on optimization [11].

- Quantifying Landscape Vulnerability via Ecosystem Services:

- Select Key Ecosystem Services: Choose services critical to the study area (e.g., water yield, soil retention, carbon storage, habitat quality).

- Model Ecosystem Services: Use models like InVEST or RUSLE to quantify the biophysical supply of each service for every landscape grid.

- Normalize and Aggregate: Normalize service values and aggregate them using weighting (e.g., equal weight or analytic hierarchy process) to create a composite Ecosystem Service Value (ESV) for each grid [11].

- Derive Vulnerability Index (Vi'): Invert the ESV (e.g., Vi' = 1 - Normalized ESV). This grounds vulnerability in functional loss rather than expert opinion [11].

- Calculating the Optimized LERI: Replace the traditional Vi with the ESV-derived Vi' in the LERI formula (Step 4 of Protocol 1). This yields a functionally grounded risk index.

- Assessing Ecosystem Resilience (ER):

- Resilience Indicators: Construct an index from indicators such as vegetation vigor (NDVI), landscape diversity (SHDI), ecological connectivity (calculated via circuit theory or MCR models), and topographic complexity [11].

- Resilience Index Calculation: Normalize and aggregate selected indicators to produce a spatial ER index.

- Coupling LER and ER for Ecological Zoning:

- Bivariate Spatial Autocorrelation: Perform a bivariate Local Moran's I analysis between the optimized LERI and ER index layers.

- Delineate Management Zones:

- Low LER - High ER (Ecological Conservation Zone): Stable, resilient areas. Priority is maintaining current state.

- High LER - Low ER (Ecological Restoration Zone): High-risk, low-resilience areas. Priority is urgent intervention and restoration.

- High LER - High ER / Low LER - Low ER (Ecological Adaptation Zone): Areas with trade-offs. Priority is adaptive management and monitoring [11].

LER and ER Coupling for Ecological Zoning

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Analytical Tools and Data Sources for Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment

| Tool/Data Category | Specific Example & Source | Primary Function in LERA |

|---|---|---|

| Remote Sensing Data | Landsat Series (USGS), Sentinel-2 (ESA) | Provides multi-spectral, multi-temporal imagery for land use/cover classification and change detection. Essential for calculating landscape pattern metrics [9] [4]. |

| GIS & Spatial Analysis Software | ArcGIS Pro, QGIS, GRASS GIS | Platform for data integration, spatial overlay, grid creation, map algebra, and final cartographic visualization of risk patterns [12]. |

| Landscape Pattern Analysis Software | FRAGSTATS | The standard software for computing a wide array of landscape metrics at the class and landscape level from categorical raster maps [12]. |

| Ecosystem Service Modeling Tools | InVEST (Natural Capital Project), RUSLE, SDR | Suite of models for quantifying and mapping the provision of ecosystem services (e.g., carbon, water, sediment retention), used to create objective vulnerability indices [11]. |

| Statistical & Geostatistical Packages | R (with spdep, gd packages), GeoDa, IBM SPSS |

Performs advanced spatial statistics (e.g., spatial autocorrelation, Geodetector analysis), regression modeling, and validation of risk drivers [4] [12]. |

| Spatial Resilience/Connectivity Tools | Circuitscape, Linkage Mapper | Models landscape connectivity and resistance to movement, which are key components for assessing ecological resilience and identifying corridors [11]. |

| Climate & Socioeconomic Data | WorldClim, GPW, National Statistical Yearbooks | Provides gridded data on climate variables (temp, precip) and socio-economic drivers (GDP, population) for analyzing risk influencing factors [4] [12]. |

| N-Lithocholyl-L-Leucine | N-Lithocholyl-L-Leucine, MF:C30H51NO4, MW:489.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Palmitoyl-3-bromopropanediol | 1-Palmitoyl-3-bromopropanediol, MF:C19H37BrO3, MW:393.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Landscape Ecological Risk (LER) assessment has emerged as a critical tool for evaluating the potential adverse effects of human activities and environmental changes on ecosystem structure and function [9]. Conventionally, LER models rely on landscape pattern indices derived from land use/cover change (LUCC) data, calculating risk as a function of landscape disturbance and vulnerability [4]. While widely applied, this paradigm is increasingly scrutinized for core methodological shortcomings that limit its scientific robustness and managerial utility [11] [7]. First, the assignment of landscape vulnerability indices is often based on expert judgment or arbitrary value assignments to land use types (e.g., assigning values of 1-6 to different categories), introducing strong subjectivity and uncertainty [11]. Second, the reliance on a static snapshot of landscape patterns fails to capture dynamic ecological processes, feedbacks, and recovery potential, representing a static approach that overlooks system dynamics [14] [15]. Third, and most critically, conventional LER assessments largely ignore the concept of ecosystem resilience (ER)—the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while retaining its essential function [11] [7]. This omission represents a fundamental missing link between risk identification and sustainable management strategies. This article, framed within a broader thesis on optimizing LER with resilience research, details these shortcomings and provides application notes and experimental protocols for developing next-generation, integrated LER-ER assessment frameworks.

Shortcoming I: Subjectivity in Landscape Vulnerability Indexing

The conventional method for characterizing landscape vulnerability, a core component of the Landscape Loss Index (LLI), is a primary source of subjectivity. Vulnerability is typically represented by a static, ordinally ranked index value assigned to each land use/cover type (e.g., cropland=3, forest=4) [11]. This approach relies heavily on intuition and general experience, lacking a quantifiable, process-based foundation [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional and Optimized Vulnerability Assessment Methods

| Assessment Component | Conventional Method | Key Shortcoming | Optimized Method (Ecosystem Service-Based) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Vulnerability Index (LVI) | Static, ordinal ranking of land use types (e.g., 1-6) [11]. | High subjectivity; no functional basis; ignores spatial heterogeneity within a land type. | Derived from the inverse of composite ecosystem service supply (e.g., water conservation, soil retention, carbon sequestration) [11] [16]. | Objective, quantifiable, spatially explicit; reflects actual ecological function and sensitivity. |

| Data Foundation | Land use/cover classification map. | Simple, but lacks ecological functional data. | Biophysical models (e.g., InVEST, RUSLE) and remote sensing to quantify ecosystem service yields [11] [17]. | Integrates process-based modeling, capturing ecological mechanisms. |

| Outcome | A uniform vulnerability score for all patches of the same land class. | Fails to differentiate, e.g., a fragmented forest patch from a core forest area. | A continuous, spatially varied vulnerability surface [11]. | Captives intra-class heterogeneity and provides a more nuanced risk landscape. |

Application Note 2.1: Protocol for Ecosystem Service-Based Vulnerability Assessment

- Objective: To replace subjective land type rankings with an objective, spatially explicit Landscape Vulnerability Index (LVI) based on ecosystem service (ES) provision.

- Materials: Land use map; biophysical data (DEM, soil type, precipitation, NDVI); geospatial software (ArcGIS, QGIS); ecosystem service modeling tools (e.g., InVEST modules).

- Procedure:

- Select Key Ecosystem Services: Identify 3-4 regionally dominant ES (e.g., for a watershed: water yield, soil retention, carbon storage, habitat quality) [11].

- Quantify ES Supply: Use standardized models (e.g., InVEST) to calculate the biophysical supply of each selected ES for every pixel or planning unit over the study period.

- Normalize and Aggregate: Normalize each ES value to a 0-1 scale. Use an additive model or weighted summation (e.g., entropy method for weights) to create a composite ES supply index [16].

- Derive LVI: Calculate LVI as

LVI = 1 - Normalized Composite ES Index. This ensures areas with low service provision (high degradation or sensitivity) receive high vulnerability scores [11]. - Validation: Perform sensitivity analysis on weight assignments and correlate the final LVI map with independent indices of ecological degradation (e.g., soil erosion rates, habitat fragmentation metrics).

Shortcoming II: Static, Pattern-Only Approaches

Traditional LER assessments are inherently static, calculating risk from landscape pattern indices (e.g., fragmentation, dominance) at a single point in time or across discrete time steps [12]. This "pattern-risk" model assumes a direct and constant relationship between spatial configuration and ecological function, neglecting the dynamic processes of ecological succession, species movement, and disturbance recovery [14]. It fails to answer whether a disturbed landscape is on a trajectory of recovery or further degradation.

Application Note 3.1: Protocol for Integrating Dynamic Ecological Flows via Circuit Theory

- Objective: To augment static LER with an assessment of landscape functional connectivity, which influences recovery potential and risk propagation.

- Materials: LER raster map; habitat quality/land use map; resistance surface data (topography, human disturbance); software (Circuitscape, Linkage Mapper).

- Procedure:

- Define Ecological Sources: Identify core habitat patches using criteria such as high ES value, high LER-resilience coupling (low LER-high resilience), or large, contiguous natural areas [17].

- Construct a Composite Resistance Surface: Base resistance is typically the inverse of habitat quality. Refine it by integrating the LER index, where higher LER increases resistance to species movement and ecological flow [17].

- Model Connectivity with Circuit Theory: Use Circuitscape software to model omnidirectional, random-walk movement across the resistance surface. This generates maps of cumulative current density and identifies pinch points (narrow corridors crucial for connectivity) and barrier points [17].

- Dynamic LER Interpretation: A high-LER area that is also a critical pinch point presents a much greater systemic risk than a similarly scored isolated patch. This analysis transforms static LER into a component of dynamic landscape network analysis, guiding interventions to maintain or restore critical flows.

Diagram 1: From Static LER to Dynamic Network Analysis (95 chars)

Shortcoming III: The Missing Resilience Link

The most significant conceptual gap is the disconnect between LER and Ecosystem Resilience (ER). ER describes a system's capacity to withstand disturbance and its ability to return to a similar functional or structural state after a perturbation [11]. Conventional LER assesses the "pressure" but ignores the inherent "capacity" of the landscape to cope. Integrating resilience transforms LER from a mere indicator of problem severity into a guide for targeted management.

Table 2: Spatial Correlation and Management Zoning Based on LER and Resilience [11]

| Bivariate Moran's I Zoning Category | LER Level | Ecosystem Resilience (ER) Level | Ecological Management Implication | Typical Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological Restoration Zone | High | Low | High pressure, low coping capacity. Highest priority for intervention. | Active restoration: re-vegetation, erosion control, habitat reconstruction. |

| Ecological Adaptation Zone | High | High | High pressure but currently high capacity. Monitor for resilience erosion. | Adaptive management: reduce chronic stressors, enhance landscape connectivity. |

| Ecological Conservation Zone | Low | High | Low pressure, high capacity. Ideal state to be maintained and protected. | Preventive conservation: enforce protection, limit development, maintain natural processes. |

| (Potential) Vacant Zone | Low | Low | Not commonly observed; may indicate latent risk or data artifact. | Investigate underlying causes; monitor for sudden disturbances. |

Application Note 4.1: Protocol for Coupling LER and Ecosystem Resilience Assessment

- Objective: To quantitatively assess ER, analyze its spatial correlation with LER, and delineate zones for differentiated ecological management.

- Materials: Time-series remote sensing data (NDVI, land use); climate data; soil data; spatial statistics software (e.g., GeoDa).

- Procedure:

- Quantify Ecosystem Resilience (ER): A robust proxy for ER is vegetation recovery rate after disturbances. Calculate the annual NDVI series. For each pixel, identify disturbance years (significant NDVI drops). Model the post-disturbance NDVI recovery trajectory and fit a curve (e.g., logistic) to extract the recovery rate and time to recover as resilience metrics [7].

- Calculate Integrated LER: Employ the optimized LER model from Application Note 2.1.

- Spatial Correlation Analysis: Use bivariate local Moran's I statistic to classify the relationship between LER and ER for each spatial unit into the four categories in Table 2 [11].

- Drive Factor Analysis: Use Geographical Detector (GeoDetector) models to identify the dominant factors (e.g., land use type, elevation, slope, climate, human activity intensity) influencing the spatial differentiation of both LER and ER, and their interactive effects [11] [12].

Diagram 2: Integrated LER-Resilience Assessment Workflow (100 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Materials for Advanced LER Research

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Item/Software | Primary Function in Protocol | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geospatial & Remote Sensing Data | Land Use/Cover (LULC) time-series data (e.g., from CAS RESDC) [12]. | The foundational spatial dataset for calculating landscape indices and tracking change. | Ensure temporal consistency and classification accuracy across different years. |

| MODIS/ Landsat NDVI time-series data. | Used to quantify vegetation dynamics and calculate ecosystem resilience metrics [7]. | Handle cloud contamination and ensure radiometric calibration for time-series analysis. | |

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM), soil, climate datasets. | Critical inputs for process-based ecosystem service modeling (e.g., InVEST). | Resolution and precision should match the study scale; data sources must be reliable. | |

| Modeling & Analysis Software | Fragstats | Calculates a wide array of landscape pattern metrics (e.g., patch density, edge density) for LER models [12]. | Choose metrics that are ecologically relevant to the study area and resistant to scale effects. |

| InVEST Model Suite | Spatially explicit modeling of ecosystem service supply (e.g., water yield, sediment retention) [17]. | Model calibration with local data is crucial for improving output accuracy. | |

| Circuitscape | Applies circuit theory to model landscape connectivity and identify critical nodes [17]. | Constructing a biologically meaningful resistance surface is the most critical and challenging step. | |

| GeoDa / GD (Geographical Detector) | Performs spatial autocorrelation (e.g., Moran's I) and detects driving factors of spatial heterogeneity [11] [6]. | Results can reveal interaction effects between factors that are stronger than individual effects. | |

| Computational Environment | Python (with sci-kit learn, pandas, geopandas) / R | Provides a flexible environment for customizing analysis workflows, statistical modeling, and automating batch processing. | Essential for handling large geospatial datasets and implementing machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest for driver analysis) [12]. |

| ArcGIS Pro / QGIS | The core platform for spatial data management, visualization, and fundamental geoprocessing. | The industry standard; QGIS is a powerful open-source alternative. | |

| Calcium mesoxalate trihydrate | Calcium mesoxalate trihydrate, MF:C3H6CaO8, MW:210.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 8-Methyloctadecanoyl-CoA | 8-Methyloctadecanoyl-CoA, MF:C40H72N7O17P3S, MW:1048.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Conceptual Foundations of Resilience in Ecology

Resilience theory provides a framework for understanding how systems absorb disturbance, reorganize, and maintain their essential functions. Within landscape ecology and risk assessment, it shifts the management paradigm from resisting change to building adaptive capacity. The concept, introduced to ecology by C.S. Holling, is fundamentally defined as “the magnitude of disturbance that a system can tolerate before it shifts into a different state with different controls on structure and function†[18] [19]. This contrasts with engineering resilience, which focuses on the speed of return to a single equilibrium state [20].

For landscape ecological risk assessment, two critical conceptual distinctions are essential:

- Ecological Resilience: Emphasizes the existence of multiple stable states or regimes. The system can undergo regime shifts when a threshold is crossed due to disturbance. The focus is on the amount of change a system can withstand without altering its fundamental structure and processes [21] [20].

- Socio-Ecological Resilience: Expands the concept to integrated human-nature systems. It incorporates social dynamics, learning, governance, and adaptive cycles, recognizing that social and ecological systems are inextricably linked and co-evolve [18] [19].

A key conceptual model is the adaptive cycle, which describes four phases of change in complex systems: exploitation (r), conservation (K), release (Ω), and reorganization (α). This cycle operates across multiple scales in a nested hierarchy known as panarchy, where dynamics at one scale (e.g., a forest patch) influence and are influenced by dynamics at larger (e.g., watershed) and smaller (e.g., soil microbial community) scales [22]. This multi-scale perspective is critical for optimizing landscape ecological risk assessments, as risks and resilience manifest differently across spatial and temporal scales [21] [23].

Table 1: Core Concepts in Resilience Theory for Landscape Ecology

| Concept | Definition | Relevance to Landscape Ecological Risk Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Resilience [20] | The magnitude of disturbance a system can absorb before restructuring into a new state. | Assesses the risk of catastrophic, irreversible regime shifts (e.g., forest to grassland). |

| Engineering Resilience [20] | The speed at which a system returns to its single equilibrium state after a disturbance. | Useful for evaluating recovery potential from discrete, non-catastrophic disturbances. |

| Threshold / Tipping Point [20] [19] | A critical level of a controlling variable or disturbance pressure beyond which system feedbacks change, leading to a new state. | Identifying early-warning signals of threshold proximity is a primary goal of resilience-based risk assessment. |

| Alternative Stable Regime [20] [19] | A distinct system state maintained by a unique set of structures, processes, and feedbacks (e.g., clear vs. turbid lake). | Defines the potential undesirable states that constitute high ecological risk. |

| Adaptive Capacity [20] | The ability of a system to adjust, learn, and reorganize in response to threats. | The foundation for proactive risk management; enhances a system's ability to cope with unforeseen shocks. |

| Panarchy [21] [22] | The nested, cross-scale structure of complex systems where cycles of change interact. | Explains how local risk can cascade to broader scales and how interventions at one scale can influence resilience at another. |

Quantitative Frameworks and Assessment Methodologies

Transitioning from theory to operational assessment requires quantifying resilience attributes. A leading framework decomposes ecological resilience into four measurable components: scales, adaptive capacity, thresholds, and alternative regimes [20]. This decomposition allows researchers to test specific hypotheses about system behavior and resilience.

Landscape Pattern Analysis serves as a primary methodology for spatial resilience assessment. It uses geospatial data to compute metrics of landscape composition (e.g., percent cover of habitat types) and configuration (e.g., connectivity, patch size distribution) [21]. The core hypothesis is that landscapes exhibiting patterns within their historic range of variability (HRV)—the dynamic equilibrium established under natural disturbance regimes—possess greater inherent resilience. Significant departure from HRV indicates reduced resilience and higher ecological risk [21]. This approach was applied in China’s South-to-North Water Diversion project area, where a Landscape Ecological Risk Index (ERI) was constructed based on land use transformation and landscape pattern metrics [24].

Multivariate Trajectory Analysis is a powerful companion technique. It tracks the movement of a landscape through a multidimensional state space defined by key metrics (e.g., habitat connectivity, diversity, fragmentation) over time. The vector of change (trajectory) can be compared to a reference trajectory or desired range, quantifying the rate and direction of departure or recovery [21].

For socio-ecological systems, community-based assessment tools are vital. The Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) provides a set of 20 qualitative and quantitative indicators across ecological, agricultural, and socio-economic domains [25]. Assessment is conducted through participatory workshops where community members score indicators, generating not just numerical data but rich qualitative insights into system dynamics, strengths, and vulnerabilities [26]. This process itself builds social capacity and project ownership, enhancing overall resilience [26].

Table 2: Quantitative Attributes of Ecological Resilience and Measurement Approaches [20]

| Resilience Attribute | Measurement Hypothesis | Exemplary Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | Resilience emerges from redundant functional traits within and across distinct spatial and temporal scales. | Spatial statistics (e.g., wavelet analysis, variograms); cross-scale redundancy analysis. |

| Adaptive Capacity | Systems with higher biodiversity and functional response diversity have a greater capacity to adapt to disturbance. | Measuring functional trait diversity; network analysis of species interactions; social survey on innovation and learning. |

| Thresholds | Systems approaching a critical threshold will exhibit predictable early-warning signals in their dynamics. | Analysis of time-series for critical slowing down (e.g., rising autocorrelation); spatial pattern analysis (e.g., rising spatial correlation). |

| Alternative Regimes | The existence of multiple attractors can be inferred from bimodal distributions of state variables or hysteresis in response to drivers. | Statistical analysis of system state distributions; manipulative experiments; paleo-ecological reconstruction. |

Application Notes & Protocols for Optimizing Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment

Integrating resilience theory transforms landscape ecological risk assessment from a static evaluation of hazard exposure to a dynamic analysis of system vulnerability and adaptive potential. The core objective is to identify not just current risk, but the proximity to critical thresholds and the capacity to adapt to ongoing change [20] [23].

Protocol: Landscape-Scale Resilience Assessment for Risk Prioritization

Objective: To map spatial variation in ecological resilience and identify areas at highest risk of regime shifts, guiding targeted mitigation efforts [21] [24].

Workflow:

- Define Assessment Units & Focal System: Delineate the landscape (e.g., watershed, administrative region) and define the ecological system (e.g., forest, wetland mosaic) and its potential alternative regimes [24].

- Select State Variables & Metrics: Choose key landscape pattern metrics that reflect system structure and function (e.g., core habitat area, connectivity index, land use diversity). For socio-ecological systems, integrate community-based SEPLS indicators [21] [25].

- Establish a Resilience Baseline (Reference Condition):

- Historical Range of Variability (HRV): Use historical data, paleo-records, or simulation modeling (e.g., using LANDIS-II or similar landscape dynamic models) to quantify the range of natural variation in state metrics under historic disturbance regimes [21].

- Desired Future Condition (DFC): In human-modified landscapes, define a DFC based on management goals that maintain key ecosystem services and biodiversity [21].

- Quantify Current State & Departure: Calculate current landscape metrics from recent geospatial data. Compute the multivariate distance (e.g., Mahalanobis distance) or trajectory angle between the current state and the HRV or DFC baseline. This departure magnitude is a primary measure of resilience loss and risk [21].

- Analyze Risk Drivers & Threshold Proxies: Statistically model relationships between departure magnitude and potential drivers (e.g., road density, climate moisture deficit, land use intensity). Use spatial statistics to detect early-warning signals like increasing spatial correlation of stress [20] [24].

- Generate Resilience-Risk Maps: Classify the landscape into zones (e.g., High Resilience/Low Risk, Transitional, Low Resilience/High Risk) based on departure magnitude and threshold proximity. Validate zones with field data on ecosystem condition [24].

Protocol: Community-Based Resilience Assessment for Integrated Risk Management

Objective: To assess the socio-ecological resilience of a production landscape or seascape, capturing human dimensions critical for risk mitigation success [25] [26].

Workflow:

- Workshop Preparation: Adapt the 20 SEPLS indicators to the local context. Assemble a diverse group of 15-30 community stakeholders [25].

- Participatory Scoring & Mapping: Over 1-2 days, facilitate discussions for each indicator. Use participatory mapping and historical timelines to provide context. Have participants collectively score each indicator (e.g., on a scale of 1-5) [26].

- Qualitative Data Capture: The primary output is not the score but the transcribed discussion. Systematically record reasons for scores, examples of changes, and perceptions of threats and capacities [26].

- Resilience Analysis: Analyze scores and qualitative data to identify strengths (high-scoring indicators) and critical vulnerabilities (low-scoring indicators). Pay particular attention to indicators related to biodiversity, knowledge learning, and governance collaboration, which are often central to adaptive capacity [25].

- Feedback & Adaptive Planning: Present results back to the community. Use the identified vulnerabilities to co-develop risk mitigation actions (e.g., restoring ecological corridors, diversifying livelihoods, strengthening local institutions). This process directly builds social capital, a key component of resilience [26].

Protocol: Urban Agglomeration Resilience and Networked Risk Assessment

Objective: To assess ecological risk and resilience in interconnected urban regions, accounting for cross-boundary risk transmission [22] [23].

Workflow:

- Define the Urban Network: Model the urban agglomeration as a network, with cities as nodes and flows of material, energy, people, and pollution as links [23].

- Multi-Scale Risk Assessment: Conduct a landscape ecological risk assessment (as in Protocol 3.1) for each city node. Simultaneously, assess risk factors that propagate through the network (e.g., upstream water pollution, regional air masses, shared infrastructure vulnerabilities) [23].

- Analyze Networked Resilience: Evaluate the resilience of the network itself. Metrics may include redundancy of ecological corridors, diversity of resource supply sources among cities, and the presence of collaborative governance institutions for crisis response [22] [23].

- Model Risk Cascades: Use systems dynamics or agent-based modeling to simulate how a disturbance (e.g., flood, economic shock) in one node propagates through the network, identifying systemic vulnerabilities and potential "circuit breaker" interventions [23].

- Develop Polycentric Governance Strategies: Formulate risk mitigation plans that require coordination across jurisdictions, such as regional green infrastructure networks, unified environmental monitoring, and joint climate adaptation strategies [22] [23].

Table 3: Research Toolkit for Resilience-Based Landscape Risk Assessment

| Tool / Reagent Category | Specific Item or Method | Primary Function in Resilience Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Geospatial & Remote Sensing Data | Multi-temporal satellite imagery (Landsat, Sentinel), LiDAR data, Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) maps. | Provides the foundational spatial data for calculating landscape pattern metrics and tracking change over time [21] [24]. |

| Landscape Pattern Analysis Software | FRAGSTATS, GuidosToolbox, ArcGIS Landscape Metrics Toolkit. | Computes quantitative metrics of landscape composition and configuration critical for assessing departure from reference conditions [21]. |

| Dynamic Simulation Modeling Platforms | LANDIS-II, HexSim, SELES. | Models landscape processes and succession under different disturbance and climate scenarios to project future states and define HRV [21]. |

| Statistical Analysis & Early-Warning Signal Tools | R packages (earlywarnings, spatialwarnings), multivariate statistical software (PC-ORD, PRIMER). |

Analyzes time-series and spatial data for statistical signatures (e.g., critical slowing down) that indicate proximity to thresholds [20]. |

| Community Assessment Toolkit | Indicators of Resilience in SEPLS (2024 Edition), participatory mapping materials, workshop facilitation guides. | Enables structured, participatory assessment of socio-ecological resilience, capturing local knowledge and building stakeholder engagement [25] [26]. |

| Network Analysis Software | Gephi, UCINET, R package igraph. |

Models urban agglomerations or habitat networks as interconnected systems to analyze risk propagation and network-level resilience [23]. |

Abstract Modern Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment (LERA) requires a fundamental paradigm shift from static hazard identification to dynamic resilience quantification. This integration is critical for understanding not only the probability of detrimental ecological outcomes from stressors but also the capacity of landscapes to absorb disturbance, adapt, and transform [21] [27]. Framed within a thesis on optimizing LERA, these application notes present a synergistic framework that couples the “disturbance-vulnerability-loss†risk model with the “resistance-adaptation-recovery†resilience framework [28]. We provide detailed protocols for multi-scale quantitative assessment, leveraging landscape pattern analysis, dynamic simulation modeling, and geospatial statistical tools. Supported by empirical data and visualized workflows, this guide equips researchers and land managers with the methodologies to operationalize resilience-informed LERA, enabling proactive management for ecological security in the face of global change.

The Imperative for an Integrated LERA-Resilience Framework

Traditional LERA often operates as a diagnostic tool, quantifying the probability and severity of adverse ecological effects based on landscape pattern indices and external stressors [29]. While valuable for identifying risk hotspots, this approach is inherently limited by its static and retrospective nature. It typically answers "where and how bad is the risk?" but fails to address "how will the system respond, and what is its capacity to cope?" This gap is critical, as two landscapes with identical static risk indices may have vastly different futures based on their underlying resilience—their ability to maintain core structures and functions through disturbance, adapt to changing conditions, and recover from shocks [21] [27].

The synergistic integration of resilience transforms LERA from a diagnostic into a prognostic and strategic tool. This fusion is operationalized by explicitly linking the "disturbance-vulnerability-loss" paradigm of LERA with the "resistance-adaptation-recovery" dimensions of ecological resilience [28]. Disturbance pressures test a system's resistance; a system's vulnerability is inversely related to its adaptive capacity; and the magnitude of potential loss is directly mitigated by the system's recoverability. Empirical research confirms a robust negative correlation between ecological resilience and landscape ecological risk, with the recoverability dimension exerting the most potent counteracting effect on risk propagation [28].

This integration demands a multi-scale perspective. Ecological processes and their resilience operate across nested spatial and temporal scales—a concept described as panarchy [21] [27]. A practical LERA must therefore analyze interactions from fine-scale grids to broader county and regional levels, as relationships between risk and resilience can intensify or even reverse across scales [28]. The following framework diagram conceptualizes this integrated, multi-scale approach.

Diagram 1: Integrated LERA-Resilience Framework

Quantitative Assessment Protocols: Metrics and Models

Operationalizing the integrated framework requires quantifiable metrics for both risk and resilience. The protocols below standardize this assessment.

Protocol 1: Multi-Scale Landscape Ecological Resilience Assessment

This protocol quantifies ecological resilience based on landscape pattern attributes that correspond to resistance, adaptation, and recovery capacities [21] [28].

- Objective: To compute a composite Ecological Resilience Index (ERI) at multiple administrative or grid scales.

- Materials: Geospatial land use/cover (LULC) maps (e.g., CLCD data [29]), GIS software (e.g., ArcGIS, FRAGSTATS), statistical package.

- Procedure:

- Landscape Pattern Analysis: For each spatial unit (e.g., 1km grid, county), calculate key landscape pattern indices from the LULC map.

- Dimension Index Calculation: Aggregate selected indices into three core resilience dimension indices using established formulas (see Table 1).

- Composite ERI Calculation: Integrate the three dimension indices using an equal or weighted summation: ERI = (Resistance Index + Adaptation Index + Recovery Index) / 3.

- Spatial & Temporal Analysis: Map ERI results and analyze spatiotemporal trends across scales (e.g., from 2010 to 2020).

Table 1: Resilience Dimensions and Corresponding Landscape Metrics

| Resilience Dimension | Operational Definition | Key Landscape Metrics | Computational Formula (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance | Capacity to withstand disturbance without change. | Edge Density (ED), Largest Patch Index (LPI), Aggregation Index. | Resistance Index ∠(LPI + Aggregation Index) / 2 [28]. |

| Adaptation | Capacity to adjust to stress through reorganization. | Shannon's Diversity Index (SHDI), Contagion, Landscape Shape Index. | Adaptation Index ∠SHDI [21] [28]. |

| Recovery | Capacity to return to a reference state after perturbation. | Core Area Percentage (CPLAND), Connectivity, Patch Cohesion Index. | Recovery Index ∠CPLAND + Connectivity [28]. |

Protocol 2: Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment Based on Landscape Patterns

This protocol assesses risk by evaluating landscape disturbance and vulnerability [28] [29].

- Objective: To calculate a Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI) and identify risk hotspots.

- Materials: As in Protocol 1, plus spatial data on stressors (optional).

- Procedure:

- Landscape Loss Index Calculation: For each landscape type i in each spatial unit k, compute a loss degree: Lossᵢₖ = Disturbanceᵢ * Vulnerabilityᵢ.

- Risk Index Integration: Calculate the Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI) for each unit: LERIₖ = Σ (Lossᵢₖ * (Areaᵢₖ / Areaₖ)).

- Spatio-Temporal Analysis & Validation: Map LERI, analyze trends and center-of-gravity shifts [29], and validate with historical ecological degradation data.

Table 2: Components of Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI)

| Component | Description | Typical Metrics/Proxies |

|---|---|---|

| Disturbance Index | Intensity of external stress on a landscape type. | Landscape Fragmentation, Divergence from natural state, or composite of fragmentation, isolation, and dominance indices [28] [29]. |

| Vulnerability Coefficient | Inherent susceptibility of a landscape type to lose function. | Expert ranking (e.g., Water: 7, Forest: 3, Cropland: 4, Built-up: 1) assigned via analytic hierarchy process [28]. |

| Landscape Loss Degree | Potential ecological loss for a specific type. | Product of Disturbance Index and Vulnerability Coefficient. |

Protocol 3: Coupling Coordination Analysis

This protocol quantifies the interaction and synergy between risk and resilience [28].

- Objective: To measure the coupling coordination degree (CCD) between LERI and ERI.

- Materials: LERI and ERI results from Protocols 1 & 2.

- Procedure:

- Standardization: Normalize LERI and ERI values to a [0,1] range.

- Coupling Degree (C) Calculation: C = 2 * √[(Uâ‚ * Uâ‚‚) / (Uâ‚ + Uâ‚‚)²], where Uâ‚=LERI, Uâ‚‚=ERI.

- Coordination Index (T) Calculation: T = αU₠+ βU₂ (α and β are weights, often α=β=0.5).

- Coupling Coordination Degree (D) Calculation: D = √(C * T).

- Classification & Zoning: Classify D values (e.g., 0-0.3: Serious Dysregulation; 0.3-0.5: Moderate Dysregulation; 0.5-0.8: Basic Coordination; 0.8-1.0: Quality Coordination). Overlay with resilience/risk categories for management zoning.

Table 3: Coupling Coordination Classification and Management Implications

| Coordination Degree (D) | Level | Risk-Resilience Profile | Suggested Management Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 - 0.3 | Serious Dysregulation | High Risk, Low Resilience. Critical zones requiring urgent intervention. | Ecological Restoration: Habitat rehabilitation, connectivity enhancement, stressor mitigation [21]. |

| 0.3 - 0.5 | Moderate Dysregulation | Moderately imbalanced. | Conservation & Adaptive Management: Protective measures, monitoring, adaptive planning to prevent degradation. |

| 0.5 - 0.8 | Basic Coordination | Relatively balanced. | Sustainable Utilization: Maintain resilience through careful land-use planning and green infrastructure. |

| 0.8 - 1.0 | Quality Coordination | Low Risk, High Resilience. Optimal zones. | Priority Conservation: Protect key processes and structural integrity to maintain this state. |

Experimental Validation & Scenario Modeling

Validating the integrated framework requires moving beyond correlation to test causal relationships and forecast future dynamics under alternative scenarios.

Protocol 4: Driving Force Analysis Using Geodetector

This protocol identifies key factors influencing LER and resilience and tests their interactions [29].

- Objective: To quantify the explanatory power (q-statistic) of natural and anthropogenic drivers on LERI/ERI spatial heterogeneity.

- Materials: Raster layers for LERI/ERI and potential driving factors (elevation, precipitation, GDP, population density, road network, etc.) [29].

- Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Discretize continuous driving factor layers using the Optimal Parameters-based Geographical Detector (OPGD) model to ensure objectivity [29].

- Factor Detection: Calculate the q-statistic for each driver: q = 1 - (Σ Nh σ²h)/(N σ²), where q ∈ [0,1]. A higher q-value indicates greater explanatory power.

- Interaction Detection: Assess the combined effect of two drivers by calculating q for their interaction and comparing it to their individual q-values. Synergistic effects are present if q(X₠∩ Xâ‚‚) > q(Xâ‚) + q(Xâ‚‚).

- Ecological Interpretation: Identify primary and interactive drivers to inform targeted management (e.g., if road density and precipitation interact strongly to increase risk).

Protocol 5: Dynamic Landscape Simulation for Resilience Optimization

This experimental protocol uses simulation modeling to project future states and test management interventions [21].

- Objective: To project LERI and ERI under different climate, disturbance, and management scenarios to identify optimal resilience-enhancing strategies.

- Materials: Spatially explicit landscape simulation model (e.g., LANDIS-II, Dinamica EGO), initial LULC map, scenario parameter files.

- Procedure:

- Model Calibration & Validation: Calibrate the model using historical LULC change data.

- Scenario Definition: Develop contrasting scenarios (e.g., Business-as-Usual, Ecological Conservation, Climate Change High Emissions).

- Model Execution & Output: Run simulations to generate projected LULC maps for future time steps (e.g., 2050, 2100).

- Post-Processing & Analysis: Apply Protocols 1-3 to the projected LULC maps to calculate future ERI, LERI, and CCD.

- Strategy Evaluation: Compare outcomes across scenarios. Use the model to test specific reconfiguration strategies (e.g., targeted habitat restoration, corridor creation) and evaluate their impact on accelerating network or landscape recovery—a concept validated in engineering resilience optimization [30].

The following diagram outlines the workflow for experimental validation and optimization.

Diagram 2: Experimental Validation and Optimization Workflow

Application Notes for Management and Research

For Land Managers & Policymakers:

- Zoning-Based Management: Utilize the coupled coordination zoning (Table 3) and "high-risk/low-resilience" hotspot maps to allocate resources efficiently. Prioritize restoration in dysregulated zones and protect quality coordination zones [28].

- Participatory Resilience Assessment: Engage stakeholders in developing system models and future scenarios. This process builds shared understanding, incorporates local knowledge, and fosters adaptive comanagement, enhancing the legitimacy and effectiveness of interventions [31].

- Strategic Planning: Integrate LERA-Resilience projections into long-term land-use and conservation plans. Use scenario modeling (Protocol 5) to stress-test policies against future climate and disturbance regimes [21].

For Researchers:

- Scale-Specific Investigations: Explicitly analyze the strength and direction of risk-resilience correlations across multiple scales (grid, county, watershed). Recognize that management insights are scale-dependent [28].

- Network Resilience Analysis: Explore applying network science models from engineering [30] to ecological landscapes. Model habitat patches as nodes and connectivity as links to evaluate and optimize the resilience of ecological networks to node (patch) loss or edge (corridor) fragmentation.

- Threshold Detection: Focus research on identifying early-warning indicators and critical thresholds in the risk-resilience relationship to prevent regime shifts [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated LERA-Resilience Studies

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Source / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD) | Provides consistent, multi-temporal LULC data for calculating landscape patterns and indices. | 30m resolution, annual data from 1990 onward [29]. |

| FRAGSTATS Software | Computes a comprehensive suite of landscape pattern metrics essential for resilience and risk indices. | Must be used with a GIS platform for spatial analysis. |

| Geodetector Software | Statistically quantifies the explanatory power of drivers on spatial heterogeneity and their interactions. | The OPGD version is recommended to avoid subjectivity in parameter discretization [29]. |

| LANDIS-II Pro | Spatially explicit, process-based model for simulating forest landscape dynamics under alternative futures. | Essential for Protocol 5; requires species life history and disturbance regime parameters. |

R/Python with sf, raster, ggplot2 packages |

For custom spatial analysis, statistical modeling, coupling coordination calculation, and high-quality visualization. | Enables automation and reproducibility of Protocols 1-4. |

| Participatory Mapping Kits | For stakeholder workshops to delineate system boundaries, identify key assets, and co-produce future scenarios. | Includes physical/digital base maps, markers, and structured facilitation guides [31]. |

| 3,9-Dihydroxydecanoyl-CoA | 3,9-Dihydroxydecanoyl-CoA, MF:C31H54N7O19P3S, MW:953.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 7-hydroxyoctanoyl-CoA | 7-hydroxyoctanoyl-CoA, MF:C29H50N7O18P3S, MW:909.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodological Integration: Building a Robust Resilience-Coupled LERA Framework

Landscape Ecological Risk (LER) assessment is a vital methodology for diagnosing the stress on ecosystems from natural and anthropogenic disturbances [11]. Its primary objective is to evaluate the likelihood of adverse effects on ecosystem structure and function, which subsequently impacts human well-being [11]. Integrating ecosystem services (ES) into LER assessment addresses a critical methodological gap. Traditional LER models often rely on assigning subjective, experience-based vulnerability values to different land-use types (e.g., assigning a fixed score of "6" to woodland and "1" to construction land). This approach lacks a concrete ecological foundation and fails to capture the dynamic, functional state of the landscape [11].

The optimization proposed here is grounded in a resilience research framework. Ecosystem Resilience (ER) is defined as the capacity of an ecosystem to absorb disturbance, reorganize, and retain its essential function, structure, and identity [11]. A resilient ecosystem can better withstand stressors, thereby reducing its vulnerability and associated ecological risk. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment model must evaluate not only the current risk (LER) but also the system's inherent capacity to cope with and recover from that risk (ER). This thesis posits that integrating a quantitatively derived, ES-based measure of landscape vulnerability with a parallel assessment of ecosystem resilience provides a more robust, ecologically meaningful, and actionable model for landscape risk assessment and management zoning [11].

Core Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Landscape Vulnerability, in this optimized model, shifts from a static land-cover classification to a dynamic, function-based index. It is defined as the degree to which a landscape is susceptible to losing its capacity to provide ecosystem services under disturbance [11]. A decline in ES provision directly indicates increased landscape vulnerability and a higher probability of ecological degradation.