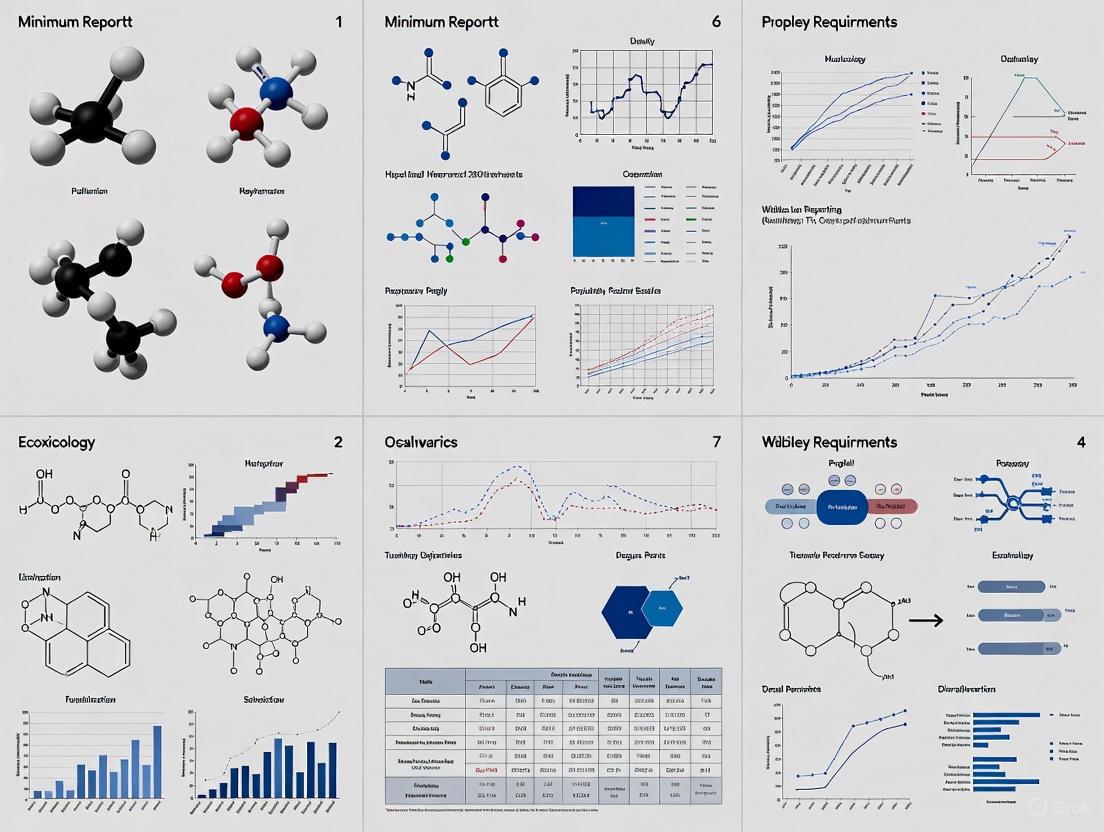

Minimum Reporting Requirements in Ecotoxicology: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust and Reproducible Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to minimum reporting requirements (MRRs) in ecotoxicology, addressing a critical need for standardization to enhance data reliability, reproducibility, and regulatory acceptance.

Minimum Reporting Requirements in Ecotoxicology: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust and Reproducible Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to minimum reporting requirements (MRRs) in ecotoxicology, addressing a critical need for standardization to enhance data reliability, reproducibility, and regulatory acceptance. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles behind MRRs, details the specific criteria for reporting test substances, organisms, and experimental design, and offers practical solutions for common reporting challenges. By comparing established evaluation frameworks like the Klimisch method and the modern CRED criteria, this guide serves as a vital resource for improving the quality, transparency, and utility of ecotoxicity data in environmental risk assessment and chemical safety evaluation.

The Foundation of Reliable Ecotoxicology: Why Minimum Reporting Requirements Matter

Defining Minimum Reporting Requirements (MRRs) and Their Role in Ecotoxicology

What are Minimum Reporting Requirements (MRRs) and why are they crucial in ecotoxicology research?

Minimum Reporting Requirements (MRRs) are standardized criteria that ensure ecotoxicology studies are reported with sufficient detail, transparency, and completeness. They provide a framework for documenting methodological approaches, experimental conditions, and results in a manner that allows readers, regulators, and other researchers to assess the reliability and relevance of the data [1]. In ecotoxicology, MRRs are fundamental for ensuring that published research can be properly evaluated for quality and utilized in environmental risk assessments [2] [1].

The implementation of MRRs addresses several critical needs in the field: enhancing the reproducibility of studies, facilitating the use of peer-reviewed research in regulatory decision-making, and supporting the development of accurate computational models and new approach methodologies (NAMs) [1] [3]. Without comprehensive reporting, even well-conducted studies may be excluded from chemical risk assessments, potentially hindering environmental protection efforts [4] [1].

How do MRRs support data reliability and relevance?

MRRs support reliability—the inherent quality of a test report relating to standardized methodology and the clarity of experimental procedures and findings—by ensuring that all critical aspects of study design and execution are thoroughly documented [2] [4]. They support relevance—the extent to which data are appropriate for a particular hazard identification or risk characterization—by requiring detailed information on test organisms, exposure conditions, and endpoints measured, allowing risk assessors to determine the applicability of the data to specific regulatory contexts [2] [4].

The evolution of MRRs has been driven by recognized limitations in historical evaluation methods. Traditional approaches like the Klimisch method, while valuable initial steps, have been criticized for lacking detailed guidance and consistency, leading to evaluations that varied significantly between assessors [2]. Contemporary frameworks like the Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data (CRED) provide more detailed, transparent evaluation criteria for both reliability and relevance, leading to more consistent and scientifically robust study assessments [2].

Technical Support: Troubleshooting Common MRR Compliance Issues

FAQ: My study wasn't conducted under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP). Can it still comply with MRRs and be considered reliable?

Answer: Yes, absolutely. While GLP provides a structured quality assurance framework, MRRs focus on the comprehensive reporting of methodological details and results, regardless of the GLP status [2]. The CRED evaluation method, for instance, emphasizes that reliability should be determined based on the completeness and quality of reporting, not solely on GLP compliance [2]. To ensure your non-GLP study meets MRR standards:

- Document all methodological details meticulously as if following a formal protocol.

- Provide explicit justification for any deviations from standardized test guidelines.

- Include all raw data in supplementary materials to enable independent verification [1].

- Demonstrate control performance meets accepted benchmarks for the test system [1].

Answer: Confirming exposure concentrations is a fundamental MRR, but resource constraints can present challenges [1]. Here are troubleshooting strategies:

- Prioritize analytical verification for at least the key test concentrations and time points (e.g., start and end of exposure) rather than omitting analysis entirely.

- Clearly state the limitations in the manuscript and discuss their potential impact on data interpretation.

- Employ conservative reporting by using nominal concentrations while explicitly noting the lack of analytical confirmation.

- Reference previous validation work if using a well-established method, but provide full details of your specific application [1].

FAQ: My research involves novel behavioral endpoints that aren't in standardized guidelines. How can I report these to meet MRR standards?

Answer: Novel endpoints, including behavioral responses, are increasingly important in ecotoxicology but require careful documentation to ensure their reliability and relevance are clear to reviewers and regulators [4].

- Provide a thorough theoretical rationale for the endpoint, linking it to potential adverse outcomes at the individual or population level [4].

- Detail the methodology with exceptional precision, including equipment specifications, software settings, environmental conditions during testing, and raw data processing methods.

- Demonstrate endpoint reproducibility through repeated trials or internal validation experiments.

- Establish a clear baseline for normal behavioral variation in control organisms [4] [1].

- Use appropriate statistical methods for the data structure and acknowledge any limitations in statistical power [1].

FAQ: My manuscript has strict word limits. How can I include all necessary MRR information?

Answer: Word limits are a common constraint, but MRRs can still be satisfied through strategic use of supplementary materials.

- Utilize online supplementary files for detailed protocols, raw data, and extensive methodological descriptions [1].

- Reference previous publications for established methods, but provide a concise summary and any modifications specific to the current study.

- Create a summary table in the main text for key test conditions and results, referring readers to supplementary materials for comprehensive data.

- Ensure the main methods section includes all information critical to understanding study validity and interpreting results [1].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for MRR Compliance

Core Reporting Domains and Their Components

Table 1: Essential Reporting Domains for Ecotoxicology Studies

| Reporting Domain | Key Elements to Document | Common Pitfalls to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Test Compound | Source, purity, chemical identity (CAS RN), characterization of mixtures, solvent details (if used) [1] | Omitting batch numbers or purity; insufficient characterization of complex substances or mixtures [1] |

| Test Organisms | Species identity (genus, species), life stage, source, husbandry conditions, acclimation procedures, feeding regime [1] | Incomplete species taxonomy; inadequate description of holding conditions and acclimation [1] |

| Experimental Design | Test type (static, renewal, flow-through), replication (number per treatment), randomization scheme, test vessel dimensions and material [1] | Unclear replication reporting; lack of randomization details; insufficient information to evaluate potential confounding factors [1] |

| Exposure Conditions | Temperature, light cycle, pH, hardness, salinity, dissolved oxygen, specific water/sediment/soil chemistry [1] | Reporting only nominal environmental parameters without measurements; omitting key water quality measurements for aquatic tests [1] |

| Exposure Confirmation | Analytical methods, measured concentrations, sampling frequency, stability data, reference to analytical quality control [1] | Reporting only nominal concentrations; inadequate description of analytical methodology [1] |

| Endpoint Measurement | Clear definition of endpoint, measurement methodology, timing of assessments, statistical methods used for analysis [1] | Novel endpoints without proper methodological description; inappropriate statistical tests [1] |

| Data Presentation | Raw data availability, control performance, effect concentrations with confidence intervals, dose-response relationships [1] | Providing only summary statistics without access to raw data; insufficient reporting of variability measures [1] |

| Radicinol | Radicinol | Radicinol, a fungal metabolite for research. Studied for its antiproliferative and enzyme inhibitory activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Valopicitabine | Valopicitabine|HCV NS5B Polymerase Inhibitor|For Research | Valopicitabine is a nucleoside inhibitor prodrug targeting the HCV NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

Evaluation Workflows for Study Reliability and Relevance

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for evaluating study reliability and relevance using modern frameworks like CRED, which incorporates MRRs:

Research Reagent Solutions for MRR Compliance

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MRR-Compliant Ecotoxicology

| Reagent/Material | Function in Ecotoxicology Studies | MRR Documentation Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Toxicants | Quality control verification of organism sensitivity and test system performance [1] | Source, purity, batch number, preparation method, historical control data [1] |

| Culture Media Components | Support for test organism maintenance, health, and normal development [1] | Full formulation, supplier details, preparation methods, quality verification data [1] |

| Solvents/Carriers | Dissolution and delivery of poorly soluble test compounds [1] | Identity, purity, concentration in test system, demonstrated lack of toxicity at used concentrations [1] |

| Analytical Standards | Calibration and verification of exposure concentrations [1] | Source, purity, certification, preparation methods, storage conditions [1] |

| Positive Controls | Demonstration of expected response for specific endpoints or modes of action [4] | Rationale for selection, source, verification of activity, concentration-response relationship [4] [1] |

Advanced MRR Applications in Modern Ecotoxicology

Supporting New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and Computational Toxicology

The emergence of NAMs—including high-throughput in vitro assays, toxicogenomics, and in silico models—has created new dimensions for MRR implementation [5] [3]. As ecotoxicology shifts toward these approaches, comprehensive reporting becomes even more critical for validation and acceptance [3]. Specific MRR considerations for NAMs include:

- Detailed protocol descriptions for non-standardized methods, including all critical parameters that might influence results.

- Comprehensive metadata for omics technologies, following established community standards for data sharing.

- Clear documentation of model architecture, training data, and performance metrics for computational approaches.

- Explicit linkage between measured endpoints and potential adverse outcomes, often facilitated through Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) frameworks [5].

The ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX) exemplifies how well-curated data following MRR principles can support the development and validation of NAMs by providing high-quality in vivo data for comparison [3].

Integration with Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs) and Evolutionary Toxicology

MRRs play a crucial role in supporting the development and assessment of Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs), which provide structured frameworks for connecting molecular initiating events to adverse outcomes at organism and population levels [5]. When reporting studies intended to inform AOP development, researchers should:

- Clearly identify and document key events along the hypothesized pathway.

- Provide evidence for taxonomic domain applicability through reporting of species phylogenetic information or target conservation data [5].

- Document exposure timelines and response sequences to support temporal concordance in AOP networks.

- Report negative results that might challenge hypothesized key event relationships [5].

The growing field of evolutionary ecotoxicology, which leverages conserved biological targets across species, particularly benefits from detailed reporting of species phylogeny, genetic information, and target sequence conservation to understand differential chemical susceptibility [5].

The Impact of Inadequate Reporting on Data Reliability and Risk Assessment

Troubleshooting Guides

Why was my ecotoxicity study considered "not reliable" for regulatory risk assessment?

A study is often categorized as "not reliable" if it fails to provide sufficient methodological detail to demonstrate the clarity and plausibility of its findings [2]. Regulatory agencies like the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) use specific criteria for this determination [4].

- Problem: A reviewer indicates your study is "not reliable" or "not assignable" due to missing information.

- Solution: Ensure your manuscript explicitly addresses all the following critical points [6] [2]:

- Control Groups: Document the use of appropriate control groups and report their results. The study must have an acceptable control for comparison [7].

- Test Organism: Provide the full taxonomic identification (genus and species) of the test organism, along with its life stage, sex, and source. The species must be verified [7].

- Exposure Conditions: Precisely report the exposure concentration/dose, duration, and the medium (e.g., water, feed). The duration of exposure must be explicit [7].

- Test Substance: Specify the chemical name, formulation, and verification of purity.

- Statistical Methods: Detail the statistical tests used, the sample size (n), and how results are presented (e.g., mean ± standard deviation).

How can I improve the relevance of my study for ecological risk assessment?

Relevance is defined as "the extent to which data and tests are appropriate for a particular hazard identification or risk characterisation" [2].

- Problem: A regulator questions the ecological relevance of your laboratory-based findings.

- Solution: To enhance relevance, establish a clear linkage between your measured endpoints and potential population-level effects [6]. The table below outlines common relevance challenges and their solutions.

| Relevance Challenge | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|

| Laboratory to Field Linkage | In the introduction or discussion, explicitly state how the individual-level effects you measured could impact survival, growth, or reproduction at the population level in a specific field situation [6]. |

| Endpoint Selection | Prioritize endpoints that are known to be biologically important for population fitness, such as reduction in survival, growth, or reproduction [7]. |

| Regulatory Context | Frame your research to address one of the main themes in environmental safety, such as understanding the effects of environmental contamination on organisms, including human health [8]. |

What are the most common documentation gaps that lead to data exclusion from databases like ECOTOX?

The ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX) uses systematic review procedures to curate data. Studies are excluded if they do not meet minimum reporting requirements [3] [7].

- Problem: Your paper is not accepted into a key database, limiting its discoverability and use.

- Solution: Use this checklist before submission to avoid common pitfalls. Your study must be a full, publicly available article in English and the primary source of the data [7]. Crucially, it must report:

My study uses a non-standard species or endpoint. How can I demonstrate its reliability and relevance?

Non-standard studies are valuable but face greater scrutiny. The key is rigorous methodology and clear justification.

- Problem: A reviewer claims your non-standard method is "less reliable."

- Solution:

- Justify Your Model: Explain why the standard test species or endpoint is unsuitable for your research question and why your chosen species or endpoint is a valid alternative.

- Apply Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data (CRED): Use the CRED evaluation method, which provides a more detailed and transparent framework for demonstrating reliability than the older Klimisch method. The CRED method is perceived as less dependent on expert judgment and more accurate [2].

- Document Controls: Even in non-standard tests, implementing and thoroughly documenting appropriate control groups is non-negotiable for establishing data reliability [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between data reliability and relevance in ecotoxicology?

- Reliability refers to "the inherent quality of a test report or publication relating to preferably standardized methodology and the way the experimental procedure and results are described to give evidence of the clarity and plausibility of the findings." It is about the trustworthiness of the data itself [2] [4].

- Relevance is "the extent to which data and tests are appropriate for a particular hazard identification or risk characterisation." It is about the usefulness of the data for a specific assessment purpose [2] [4].

Are studies not conducted under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) automatically considered unreliable?

No. While GLP studies are often highly regarded, a non-GLP study from the peer-reviewed literature can be considered reliable if it provides sufficient methodological detail and meets all necessary scientific criteria [2]. The CRED evaluation method was developed in part to ensure that non-GLP studies are evaluated based on their scientific merit and reporting quality, rather than automatically being deemed less reliable [2].

What are the consequences of inadequate reporting in ecotoxicology research?

Inadequate reporting has significant repercussions [2]:

- Exclusion from Risk Assessments: Regulatory bodies may be unable to use your data, potentially leading to an incomplete risk assessment of a chemical.

- Wasted Resources: The time, funding, and animals used in the research fail to contribute to scientific knowledge or public protection.

- Impedes Scientific Progress: Inconsistent and non-transparent reporting makes it difficult to compare studies, conduct meta-analyses, or build predictive models.

- Increased Uncertainty: Poor reporting can lead to disagreements among risk assessors on the usability of a study, creating uncertainty in the final hazard assessment [2].

How can I check if my study meets minimum reporting requirements before submission?

Consult the author guidelines for your target journal (e.g., Ecotoxicology [6] or Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety [8]) and refer to the CRED evaluation criteria [2]. These resources provide detailed checklists for reporting key study elements. The ECOTOX database also provides a clear list of acceptability criteria that can serve as a practical guide [7].

Our research involves behavioral endpoints. Are these considered relevant in regulatory ecotoxicology?

Yes, behavioral endpoints are increasingly recognized as ecologically relevant. Behavior is connected to fundamental ecological processes and can impact individual fitness, with consequences for population dynamics and ecosystem function [4]. For example, effects on learning, reproduction, sociality, and predator avoidance have been linked to population-level outcomes [4]. The key is to justify and, where possible, standardize the behavioral method to improve its acceptability [4].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standardized Protocol for Assessing Study Reliability

This methodology is adapted from the Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data (CRED) method [2].

Objective: To provide a transparent and consistent framework for evaluating the reliability of an ecotoxicity study. Procedure:

- Identify Evaluation Criteria: Use a predefined set of reliability and relevance criteria. The final CRED method includes 20 reliability criteria and 13 relevance criteria [2].

- Systematic Review: Evaluate the study manuscript against each criterion. Score the study based on the extent to which it fulfills the requirements for each item.

- Categorize Reliability: Summarize the evaluation into a reliability category. While the Klimisch categories (Reliable without restrictions, Reliable with restrictions, Not reliable, Not assignable) are historically used [2], the CRED method provides a more nuanced and accurate evaluation [2].

- Document the Assessment: Record the justification for the score on each criterion to ensure transparency and allow for peer review of the evaluation itself.

Quantitative Data on Evaluation Methods

The following table summarizes a ring test comparison between the traditional Klimisch method and the newer CRED method, highlighting the benefits of using a more detailed framework [2].

| Evaluation Metric | Klimisch Method | CRED Method | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detail & Guidance | Limited criteria and guidance [2] | More detailed criteria and guidance [2] | CRED provides a clearer checklist for what to report. |

| Perceived Consistency | Lower consistency among risk assessors [2] | Higher perceived accuracy and consistency [2] | Using CRED principles makes study evaluation more predictable. |

| Dependence on Expert Judgement | High dependence [2] | Less dependent on expert judgement [2] | Reduces subjectivity in how a study is received. |

| Practicality | Well-established but criticized [2] | Considered practical regarding time and criteria use [2] | Adhering to a structured method like CRED is feasible for authors. |

Diagrams and Workflows

Study Evaluation and Data Curation Workflow

Reliability Assessment Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Reliable Ecotoxicology Research

| Item or Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Verified Test Organisms | Using organisms from a reputable source with confirmed taxonomic identification ensures the validity of your test model and is a key acceptability criterion [7]. |

| Analytical Grade Chemicals | Using chemicals of known and high purity, with the purity verified and reported, is critical for accurately defining exposure concentrations and reproducing the study [7]. |

| Appropriate Control Groups | Concurrent control groups (e.g., solvent, negative) are essential for distinguishing treatment effects from background variation. Their use and results must be documented [7]. |

| Standardized Test Protocols | Following established guidelines (e.g., from OECD, US EPA) provides a strong foundation for reliability, though adherence must be complete and reported in detail [2]. |

| CRED Evaluation Checklist | Using the Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data as a pre-submission checklist ensures your manuscript meets detailed criteria for reliability and relevance evaluation [2]. |

| Golgicide A-2 | Golgicide A-2, MF:C17H14F2N2, MW:284.30 g/mol |

| Exophilin A | Exophilin A, MF:C30H56O10, MW:576.8 g/mol |

This guide outlines the core scientific principles of Reliability, Relevance, and Reproducibility for ecotoxicity research. These principles are fundamental for ensuring the quality, transparency, and utility of scientific data in environmental hazard and risk assessments [9].

Reliability

Reliability refers to the inherent quality of a test report relating to standardized methodology and the clear description of experimental procedures and results to demonstrate the clarity and plausibility of the findings [2]. It concerns whether a study was conducted and documented in a way that makes its findings credible.

Relevance

Relevance is defined as the extent to which data and tests are appropriate for a particular hazard identification or risk characterization [2]. It assesses whether a study, even if well-conducted, addresses the right questions for its intended use in a regulatory or research context.

Reproducibility

Reproducibility is a key component of scientific integrity that promotes a self-correcting culture. It involves the transparency of methods and results, allowing other scientists to confirm findings through repeated experiments, thereby enhancing scientific credibility [9].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the difference between the Klimisch and CRED evaluation methods?

The Klimisch method, developed in 1997, categorizes study reliability into four tiers but has been criticized for limited guidance and over-reliance on expert judgment [2]. The newer Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating ecotoxicity Data (CRED) method provides more detailed and transparent criteria for evaluating both reliability and relevance, leading to more consistent assessments across different risk assessors [2].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the reproducibility of my ecotoxicity studies?

To enhance reproducibility, promote a culture of scientific rigor and transparency [9]. This includes:

- Detailed Methodology: Clearly document all experimental procedures, data analysis steps, and materials used.

- Data Availability: Make all relevant data, including raw data, accessible where possible.

- Avoid Omissions: Report all experimental outcomes, including false steps or data that did not fit initial hypotheses, to prevent bias in the scientific literature [9].

FAQ 3: What are common pitfalls that reduce a study's reliability?

Common issues include [9] [2]:

- Insufficient Documentation: Lack of clarity in describing methods, making it impossible to evaluate or repeat the study.

- Methodological Flaws: Deviations from standard protocols without justification (e.g., control mortality above accepted levels).

- Selection Bias: Reporting only data that fits the expected outcome while omitting conflicting or anomalous results.

FAQ 4: My study wasn't conducted under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP). Can it still be considered reliable?

Yes. While GLP studies are often highly regarded, the CRED method allows for a more nuanced evaluation. A non-GLP study from the peer-reviewed literature can be deemed reliable if it demonstrates scientific rigor, transparent reporting, and methodological soundness according to specific evaluation criteria [2].

Evaluation Criteria & Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Klimisch and CRED Evaluation Methods

| Feature | Klimisch Method | CRED Method |

|---|---|---|

| Development Year | 1997 [2] | 2016 (circa) [2] |

| Primary Focus | Reliability [2] | Reliability & Relevance [2] |

| Guidance Detail | Limited criteria and guidance [2] | Detailed criteria and guidance for evaluation [2] |

| Handling of GLP/Standard Tests | Often automatically categorizes them as reliable [2] | Provides criteria to evaluate them critically, even if flaws exist [2] |

| Perceived Consistency | Lower consistency among assessors [2] | Higher consistency and less dependency on expert judgement [2] |

Table 2: Key Reliability and Relevance Criteria (based on CRED)

The CRED method uses specific criteria to evaluate studies. The table below summarizes some of the key areas of consideration.

| Evaluation Dimension | Key Criteria Areas |

|---|---|

| Reliability | Test substance characterization, Test organism information, Experimental design and methodology, Statistical analysis, Data reporting [2] |

| Relevance | Appropriateness of test organism, exposure pathways, measured endpoints, and environmental realism for the intended regulatory purpose [2] |

Experimental Protocols: The CRED Evaluation Workflow

The following diagram outlines the general workflow for evaluating a study using a systematic method like CRED:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials & Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Aquatic Ecotoxicity Testing

This table details common reagents and materials used in standardized aquatic ecotoxicity tests, which are often evaluated in reliability assessments.

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Reconstituted Water | A synthetic laboratory water prepared with specific salts; used as a standardized dilution and control water to eliminate confounding variables from natural water sources. |

| Test Substance | The chemical being investigated; must be accurately characterized (e.g., purity, composition, solvent used) as this is a critical reliability criterion [2]. |

| Reference Toxicant | A standard, well-characterized chemical (e.g., potassium dichromate) used periodically to confirm the consistent sensitivity and health of the test organisms. |

| Culture Media | The water or substrate in which test organisms are reared and maintained before the test; ensures organisms are healthy and of similar age/size. |

| Aeration Equipment | Provides necessary oxygen to test chambers and helps maintain homogeneous exposure concentrations in the water column. |

| Rhodomycin A | Rhodomycin A, CAS:23666-50-4, MF:C36H48N2O12, MW:700.8 g/mol |

| Diazaphilonic acid | Diazaphilonic acid, MF:C42H32O18, MW:824.7 g/mol |

Conceptual Framework for Reliability Assessment

The reliability of an individual study rests on multiple interconnected pillars, as shown in the following conceptual diagram:

Regulatory frameworks established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) underpin the entire field of regulatory ecotoxicology. These frameworks mandate the use of standardized test guidelines and minimum reporting requirements to ensure that data on chemical substances is reliable, relevant, and comparable. This technical support guide explores how these regulatory drivers shape experimental design and reporting, providing troubleshooting advice for common compliance challenges.

FAQ: Navigating Regulatory Requirements

Q1: What is the fundamental purpose of EPA and REACH test guidelines? EPA's test guidelines are designed to generate data submitted to support specific regulatory actions, including the registration of pesticides under FIFRA, the setting of pesticide residue tolerances under FFDCA, and the regulation of industrial chemicals under TSCA [10]. Similarly, REACH requires manufacturers and importers to generate information on the intrinsic properties of substances to ensure their safe use, with standard information requirements detailed in Annexes VII to X of the regulation [11]. The core purpose is to provide a consistent, scientifically sound basis for regulatory decision-making.

Q2: How do these frameworks address the evaluation of study reliability and relevance? The evaluation of study reliability and relevance is a cornerstone of both frameworks. Reliability is defined as "the inherent quality of a test report... relating to preferably standardized methodology and the way the experimental procedure and results are described," while relevance is "the extent to which data and tests are appropriate for a particular hazard identification or risk characterisation" [2]. While the Klimisch method has been widely used for reliability evaluation, it has been criticized for lack of detail and consistency. The newer Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating ecotoxicity Data (CRED) method provides more detailed criteria and guidance, resulting in more consistent and transparent evaluations [2].

Q3: What happens if my ecotoxicity study does not follow a standardized test guideline? Studies not conducted according to approved guidelines may still be considered for regulatory purposes, but they undergo more rigorous scrutiny. Under REACH, registrants must evaluate all available data on a substance's intrinsic properties, and any studies used must be based on scientifically justified methods [11]. However, the CRED evaluation method demonstrates that peer-reviewed studies from scientific literature can be incorporated into regulatory assessments when evaluated with robust, science-based principles, even if they were not conducted under strict Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) [2].

Q4: Are there specific reporting requirements for new or emerging substance categories, like microplastics? Yes, regulatory frameworks are evolving to address emerging concerns. ECHA has released specific guidance on reporting requirements for synthetic polymer microparticles (SPMs) under Entry 78 of the EU REACH Regulation [12]. This includes a precise definition of SPMs based on composition and size specifications, lists of exempted polymers and uses, and a detailed reporting timeline requiring the use of the IUCLID platform for data submission [12].

Q5: How are animal welfare concerns influencing test guideline development? Regulatory agencies are actively promoting the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in animal testing. The EPA is an active member of the Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM), which facilitates the development and regulatory acceptance of toxicology test methods that reduce, refine, or replace animal use [10]. Furthermore, REACH explicitly states that testing on vertebrate animals should be a last resort, requiring registrants to consider all existing data and alternative non-animal methods before commissioning new vertebrate studies [11].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Reporting Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent Reliability Assessments of Ecotoxicity Studies

- Symptoms: The same study receives different reliability ratings (e.g., "reliable with restrictions" vs. "not reliable") from different assessors, leading to uncertainty about its use in risk assessment.

- Solution: Utilize the CRED evaluation method instead of the older Klimisch method. The CRED method provides more detailed, criteria-based guidance for evaluating both reliability and relevance, which has been shown to reduce inconsistency and dependence on individual expert judgment [2]. Ensure your study documentation addresses all CRED criteria prospectively.

- Prevention: When designing studies, consult not only the test guideline (e.g., OECD, EPA) but also the CRED evaluation criteria to ensure all necessary information for a definitive reliability assessment will be reported.

Problem 2: Navigating Differing Information Requirements Across Tonnage Bands

- Symptoms: Uncertainty about which specific tests and data are required for a substance under REACH, particularly as production volume changes.

- Solution: Refer to the structured tonnage-based requirements in REACH Annexes. The data requirements increase with production volume, as summarized in the table below. Always collect all existing relevant information first before considering new testing [11].

- Prevention: Proactively plan for the next tonnage band as production scales up. Use the Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment published by ECHA for detailed advice.

Problem 3: Submission and Formatting Errors in Regulatory Dossiers

- Symptoms: Rejection or delays in the processing of regulatory submissions due to technical errors in dossier preparation.

- Solution: For REACH submissions, strictly use the IUCLID software for preparing the registration dossier. This tool ensures data is entered in the structured format required by ECHA [12]. For EPA submissions, carefully review the specific data format requirements outlined in the relevant rule or guideline, such as those for continuous release reporting under 40 CFR Part 302 [13].

- Prevention: Familiarize yourself with the IUCLID platform or relevant EPA reporting systems well in advance of submission deadlines. ECHA and EPA often provide guidance documents and templates.

Essential Data Tables for Regulatory Compliance

Table 1: Standard Information Requirements under REACH by Tonnage Band

| Tonnage Band | Key Ecotoxicological and Toxicological Information Requirements |

|---|---|

| 1-10 tonnes/year (Annex VII) | Short-term toxicity on invertebrates (e.g., Daphnia), growth inhibition study on aquatic plants, ready biodegradability [11]. |

| 10-100 tonnes/year (Annex VIII) | Additional requirements: short-term toxicity on fish, degradation (hydrolysis, adsorption/desorption), activated sludge respiration inhibition test, and a 28-day repeated dose toxicity study [11]. |

| 100-1000 tonnes/year (Annex IX) | Additional requirements: long-term toxicity on invertebrates, long-term toxicity on fish, bioaccumulation potential, sub-chronic toxicity (90-day), and developmental toxicity [11]. |

| ≥1000 tonnes/year (Annex X) | Additional requirements: long-term toxicity to sediment organisms, extended one-generation reproductive toxicity study, and carcinogenicity studies if triggered [11]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Ecotoxicity Study Evaluation Methods

| Feature | Klimisch Method (1997) | CRED Method (2016) |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability Criteria | Limited, high-level criteria. | 20 detailed, specific criteria. |

| Relevance Evaluation | No specific guidance or categories provided. | 13 detailed criteria for evaluating relevance. |

| Basis for Evaluation | Heavily reliant on expert judgment; favors GLP and standard protocols. | More dependent on transparent criteria; facilitates use of peer-reviewed literature. |

| Perceived Consistency | Lower consistency among different risk assessors. | Higher consistency and transparency in evaluations. |

Experimental Workflow for a Regulatory Ecotoxicity Study

The following diagram visualizes the key steps in designing, conducting, and reporting an ecotoxicity study that meets regulatory standards for reliability and relevance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and tools frequently used in regulatory ecotoxicity research.

| Item | Function in Regulatory Ecotoxicology |

|---|---|

| OECD Test Guidelines | Provide internationally harmonized standard test methodologies, forming the basis for many EPA and REACH guideline requirements and ensuring mutual acceptance of data [10]. |

| IUCLID Software | The mandatory software application for compiling, submitting, and managing regulatory dossiers for substances under REACH and other international chemical programmes [12]. |

| CRED Evaluation Criteria | A detailed checklist of 20 reliability and 13 relevance criteria used to ensure the quality and acceptability of ecotoxicity studies for regulatory purposes, improving transparency [2]. |

| Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) | A quality system covering the organizational process and conditions under which non-clinical health and environmental safety studies are planned, performed, monitored, and reported, often enhancing a study's perceived reliability [2]. |

| Defined Test Organisms | Standardized, ecologically relevant species (e.g., Daphnia magna, Oncorhynchus mykiss) specified in test guidelines to ensure the comparability and ecological relevance of toxicity results. |

| Carpetimycin D | Carpetimycin D, CAS:87139-37-5, MF:C14H20N2O9S2, MW:424.5 g/mol |

| Zolertine Hydrochloride | Zolertine Hydrochloride, CAS:7241-94-3, MF:C13H19ClN6, MW:294.78 g/mol |

The regulatory evaluation of ecotoxicity studies is a fundamental prerequisite for environmental risk and hazard assessment of chemicals, forming the basis for critical decisions in frameworks such as REACH, the Water Framework Directive, and marketing authorization for plant protection products and pharmaceuticals [2]. For decades, the method established by Klimisch and colleagues in 1997 served as the primary tool for assessing study reliability, representing an important step toward standardized evaluation at that time [2]. However, as regulatory science advanced, the Klimisch method revealed significant limitations that prompted the development of more robust evaluation frameworks.

The Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data (CRED) project emerged from a 2012 initiative addressing the recognized shortcomings of the Klimisch method [2]. This evolution responded to the growing need for greater consistency, transparency, and scientific rigor in evaluating ecotoxicity studies across different regulatory frameworks, countries, institutes, and individual assessors [14]. The transition from Klimisch to CRED represents a paradigm shift in how the scientific community approaches study quality assessment, with implications for hazard identification, risk characterization, and ultimately, environmental protection.

Critical Analysis of the Klimisch Method: Limitations and Challenges

The Klimisch method provided a systematic approach for evaluating experimental toxicological and ecotoxicological data, categorizing studies into four reliability classes: "reliable without restrictions" (R1), "reliable with restrictions" (R2), "not reliable" (R3), and "not assignable" (R4) [2]. While this classification system brought initial structure to study evaluation, several critical limitations emerged through practical application:

Insufficient Detail and Guidance: The method offered only limited criteria for reliability evaluation and virtually no specific guidance for assessing study relevance [2]. This lack of detailed criteria left significant room for interpretation, resulting in inconsistent evaluations among risk assessors [2].

Bias Toward Standardized Protocols: The Klimisch method demonstrated a strong preference for studies performed according to Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and validated ecotoxicity protocols (e.g., OECD, US EPA) [2]. This tendency sometimes led to automatic categorization of GLP studies as "reliable without restrictions" even when obvious methodological flaws were present [2].

Exclusion of Peer-Reviewed Literature: The methodological bias contributed to regulatory dossiers that relied almost exclusively on contract laboratory data provided by registrants, while potentially excluding valuable peer-reviewed studies from the scientific literature [2]. This limitation was particularly problematic given that hazard and risk assessments often suffer from limited data availability.

Inconsistent Application: Research demonstrated that the Klimisch method failed to guarantee consistent evaluation results among different risk assessors [2]. The same study could be categorized as "reliable with restrictions" by one risk assessor and "not reliable" by another, directly influencing the outcome of hazard or risk assessments for specific chemicals [2].

The CRED Framework: Development and Core Components

The CRED evaluation method was developed through a systematic process that incorporated existing evaluation methods, OECD ecotoxicity test guidelines, and practical expertise in evaluating studies for regulatory purposes [2]. The framework was refined through multiple expert meetings, including discussions with the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) Global Environmental Risk Assessment Advisory Group and the SETAC Global Pharmaceutical Advisory Group [2].

Defining Reliability and Relevance

CRED provides clear, operational definitions for its core evaluation concepts [14]:

Reliability: "The inherent quality of a test report or publication relating to preferably standardized methodology and the way the experimental procedure and results are described to give evidence of the clarity and plausibility of the findings."

Relevance: "The extent to which data and tests are appropriate for a particular hazard identification or risk characterisation."

These definitions establish a crucial distinction: reliability concerns the intrinsic scientific quality of a study, while relevance depends on the purpose for which the study is being assessed [14]. A study may be highly reliable but irrelevant for a specific assessment context, or conversely, potentially relevant but insufficiently reliable.

Comprehensive Evaluation Criteria

The CRED method introduces a significantly more detailed framework for evaluation compared to its predecessor:

Table 1: Core Components of the CRED Evaluation Framework

| Component | Klimisch Method | CRED Method |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability Criteria | 12-14 (ecotoxicity) | 20 specific criteria |

| Relevance Criteria | 0 | 13 specific criteria |

| OECD Reporting Criteria Included | 14 of 37 | 37 of 37 |

| Additional Guidance | No | Comprehensive guidance provided |

| Evaluation Summary | Qualitative for reliability only | Qualitative for both reliability and relevance |

The 20 reliability criteria in CRED cover essential aspects of experimental design, performance, and reporting, while the 13 relevance criteria address the suitability of the test organism, endpoints, exposure conditions, and other factors for the specific assessment purpose [14]. This comprehensive approach ensures that both the intrinsic quality and contextual appropriateness of studies are thoroughly evaluated.

Comparative Analysis: CRED vs. Klimisch Method

A comprehensive ring test conducted with 75 risk assessors from 12 countries provided empirical evidence comparing the performance of the Klimisch and CRED evaluation methods [2]. The two-phased ring test involved participants evaluating ecotoxicity studies using both methods, allowing direct comparison of outcomes and user experiences.

Methodological Comparison

Table 2: Methodological Comparison Between Klimisch and CRED Evaluation Methods

| Evaluation Aspect | Klimisch Method | CRED Method |

|---|---|---|

| Transparency | Limited, due to minimal guidance | High, with detailed criteria and guidance |

| Consistency | Low, varying between assessors | High, with structured evaluation process |

| Dependency on Expert Judgment | High | Reduced through explicit criteria |

| Bias Toward GLP Studies | Significant | Reduced, focusing on methodological quality |

| Relevance Evaluation | Not systematically addressed | Comprehensive criteria provided |

| Application to Peer-Reviewed Literature | Limited | Encouraged and facilitated |

Ring Test Findings and User Perception

The ring test revealed significant differences in how risk assessors perceived and applied the two methods [2]:

Consistency: Participants reported that CRED provided more consistent evaluation results between different assessors compared to the Klimisch method [2].

Transparency: The detailed criteria and guidance in CRED were perceived to increase transparency in the evaluation process [2].

Practicality: Despite its comprehensive nature, participants found CRED practical regarding the use of criteria and time needed for performing evaluations [2].

Accuracy: Risk assessors perceived CRED as providing a more accurate assessment of study reliability and relevance compared to the Klimisch method [2].

These findings demonstrate that CRED successfully addresses the primary limitations of the Klimisch method while maintaining practical applicability for regulatory use.

Implementation in Regulatory Context and Technical Guidance

The CRED evaluation method has been progressively incorporated into various regulatory frameworks and assessment processes:

EU Technical Guidance Document: CRED is being piloted and tested in the revision of the EU Technical Guidance Document for Environmental Quality Standards (EQS) for key studies [15].

Swiss EQS Proposals: The method is being applied in the revision of EQS proposals for Switzerland [15].

Joint Research Centre: The CRED criteria are implemented in the Literature Evaluation Tool of the Joint Research Centre [15].

NORMAN EMPODAT: The reliability evaluation of ecotoxicity studies for this database incorporates CRED criteria [15].

Pharmaceutical Industry Assessment: The CRED evaluation method is being considered for inclusion in the project Intelligence-led Assessment of Pharmaceuticals in the Environment (iPiE) [15].

The implementation of CRED across these diverse regulatory contexts demonstrates its versatility and potential to harmonize assessment practices across different frameworks and geographical regions.

Technical Support Center: CRED Implementation Guide

Troubleshooting Common CRED Evaluation Challenges

Q: How should I handle studies where some criteria are fully met while others are partially met or not reported?

A: The CRED method recognizes that studies rarely fulfill all criteria perfectly. Document each criterion individually, noting whether it is fully met, partly met, not met, or not reported. The overall reliability and relevance categorization should reflect the pattern of fulfillment across all criteria, with particular attention to critical methodological elements such as experimental design, control performance, and statistical analysis. Studies with limitations may still be categorized as "reliable with restrictions" if the limitations do not fundamentally undermine the study's scientific validity [2] [14].

Q: How do I distinguish between reliability and relevance when they seem interconnected?

A: While reliability and relevance are related, they address distinct aspects of study evaluation. Reliability concerns the intrinsic scientific quality and methodological soundness of the study design, performance, and reporting. Relevance addresses how appropriate the study is for your specific assessment purpose. A study may be methodologically sound (reliable) but use test organisms, endpoints, or exposure scenarios inappropriate for your specific assessment context (not relevant). Conversely, a study might address perfectly relevant parameters but suffer from fatal methodological flaws that render it unreliable [14].

Q: What is the appropriate approach for evaluating non-standard test protocols or novel endpoints?

A: The CRED method provides flexibility for evaluating studies that deviate from standard guidelines. Focus on the scientific principles underlying each criterion rather than strict adherence to specific protocols. For novel endpoints, assess whether the endpoint is clearly defined, biologically meaningful, and measured with appropriate methodology. For non-standard protocols, evaluate whether the test design adequately controls for confounding factors, includes proper controls, and demonstrates exposure verification [2].

Experimental Protocol for CRED Evaluation

The systematic evaluation of ecotoxicity studies using CRED involves a structured process:

Step 1: Define Assessment Purpose - Clearly articulate the regulatory context and specific assessment needs, as relevance is purpose-dependent [14].

Step 2: Collect Complete Study - Obtain the full publication or study report, including supplemental materials, to ensure all necessary information is available for evaluation [14].

Step 3: Evaluate Reliability - Systematically assess the study against the 20 reliability criteria, documenting the fulfillment of each criterion and noting any limitations or concerns [14].

Step 4: Evaluate Relevance - Assess the study against the 13 relevance criteria in relation to your specific assessment purpose [14].

Step 5: Document Limitations - For any criterion not fully met, provide a clear description of the limitation, its potential impact on the results, and whether it can be addressed through data re-analysis or additional information [2].

Step 6: Assign Overall Categories - Based on the pattern of criterion fulfillment, assign overall categories for reliability and relevance [2].

Step 7: Determine Usability - Combine the reliability and relevance categorizations to determine whether the study is usable without restrictions, usable with restrictions, or not usable for the specific assessment purpose [2].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Quality Ecotoxicity Studies

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for High-Quality Ecotoxicity Studies

| Component Category | Specific Elements | Function in Study Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Test Organism Characterization | Species identification, Life stage, Source, Culturing conditions | Ensures biological relevance and reproducibility of results |

| Test Substance Verification | Chemical identity, Purity, Stability, Solubility, Exposure verification | Confirms accurate dosing and exposure conditions |

| Control Systems | Negative controls, Positive controls, Vehicle controls, Reference materials | Demonstrates assay responsiveness and identifies potential confounding factors |

| Exposure Characterization | Concentration verification, Exposure media chemistry, Test vessel materials | Validates exposure conditions and potential for substance loss |

| Endpoint Measurement | Method validation, Measurement frequency, Blinding, Calibration | Ensures accuracy and precision of effect measurements |

| Statistical Design | Replication, Randomization, Power analysis, Appropriate statistical tests | Provides robust basis for inference and conclusion drawing |

The evolution from Klimisch to CRED represents significant progress in the science of study evaluation for ecotoxicology. CRED addresses the critical limitations of the Klimisch method by providing detailed, transparent criteria for evaluating both reliability and relevance, reducing inconsistency among assessors, and facilitating the appropriate use of peer-reviewed literature in regulatory decision-making [2] [14].

The implementation of CRED across multiple regulatory frameworks promises to enhance the harmonization of hazard and risk assessments for chemicals, ultimately contributing to more robust environmental protection measures. As the method continues to be adopted and refined, it establishes a new standard for transparent, science-based evaluation of ecotoxicity studies that balances regulatory needs with scientific progress.

For researchers conducting ecotoxicity studies, adherence to CRED's reporting recommendations increases the likelihood that their work will be usable for regulatory purposes, bridging the gap between scientific advancement and environmental protection. For risk assessors, the structured approach provided by CRED supports consistent, transparent decision-making that can withstand scientific and public scrutiny.

A Practical Framework for Implementation: The CRED Criteria and Key Reporting Elements

The Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Ecotoxicity Data (CRED) is a science-based evaluation method designed to strengthen the transparency, consistency, and robustness of environmental hazard and risk assessments of chemicals. Developed as a modern replacement for the older Klimisch method, CRED provides detailed criteria and guidance for evaluating both the reliability and relevance of aquatic ecotoxicity studies [16] [2]. The method aims to reduce dependence on expert judgment and increase the utilization of high-quality peer-reviewed studies in regulatory decision-making [2].

The Core Components of CRED

The CRED evaluation method systematically assesses ecotoxicity studies across two fundamental dimensions:

- Reliability: This refers to "the inherent quality of a test report or publication relating to preferably standardized methodology and the way the experimental procedure and results are described to give evidence of the clarity and plausibility of the findings" [2]. CRED uses 20 specific reliability criteria to evaluate this aspect [17].

- Relevance: This is defined as "the extent to which data and tests are appropriate for a particular hazard identification or risk characterisation" [2]. CRED uses 13 specific relevance criteria to determine this [17].

Following evaluation, a study is assigned to one of four categories for both reliability and relevance: (1) Reliable/Relevant without restrictions, (2) Reliable/Relevant with restrictions, (3) Not reliable/relevant, or (4) Not assignable [17].

CRED vs. Klimisch: A Comparative Analysis

The CRED method was developed to address significant shortcomings in the widely used but dated Klimisch method. The table below summarizes the key differences between these two evaluation frameworks.

Table 1: Key Differences Between the CRED and Klimisch Evaluation Methods

| Characteristic | Klimisch Method | CRED Method |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Reliability only | Reliability and Relevance |

| Number of Reliability Criteria | 12-14 (for ecotoxicity) [16] | 20 [17] |

| Number of Relevance Criteria | 0 [2] | 13 [17] |

| Guidance Provided | Limited | Detailed guidance for consistent application [16] |

| Bias Towards GLP/Standardized Studies | Can favor them even with flaws [2] | More balanced, science-based evaluation |

| Transparency & Consistency | Lower, more dependent on expert judgement [2] | Higher, structured to reduce discrepancies [16] |

The Klimisch method has been criticized for its lack of detail, insufficient guidance for relevance evaluation, and failure to ensure consistency among different risk assessors [2]. One study demonstrated that the CRED method was perceived by risk assessors as less dependent on expert judgment, more accurate and consistent, and practical regarding the use of criteria and time needed for evaluation [2].

Detailed Breakdown of CRED Evaluation Criteria

The power of the CRED checklist lies in its granular, structured criteria. These criteria are divided into six classes for reporting recommendations, covering all critical aspects of an ecotoxicity study [17].

Table 2: Overview of CRED Criteria and Reporting Recommendation Classes

| Criteria Class | Focus Area | Examples of Critical Information |

|---|---|---|

| General Information | Study identification and context | Test substance identification, study objective, reference |

| Test Design | Experimental structure and validity | Control groups, exposure duration, replication |

| Test Substance | Chemical characterization and dosing | Substance form, purity, concentration verification |

| Test Organism | Biological subjects used | Species identification, life stage, source, health status |

| Exposure Conditions | Environmental parameters of the test | Temperature, pH, light, feeding, test vessel volume |

| Statistical Design & Biological Response | Data analysis and results | Test endpoints, statistical methods, raw data availability |

Implementing CRED: A Step-by-Step Workflow

Successfully applying the CRED checklist requires a systematic approach. The following diagram visualizes the recommended workflow for evaluating a study.

- Apply Reliability Criteria: Systematically go through all 20 reliability criteria. For each criterion, determine if the study fulfills it. Document any shortcomings or missing information that affect the study's inherent quality [16] [17].

- Apply Relevance Criteria: Systematically go through all 13 relevance criteria. Assess whether the study's design, test organism, endpoint, and exposure conditions are appropriate for your specific hazard identification or risk characterization purpose [16] [17].

- Assign Final Categories: Based on the outcome of the criteria evaluation, assign the study to one of the four final categories for both reliability and relevance [17].

- Document the Evaluation: Create a summary report that includes the assigned categories and, crucially, a list of any data limitations identified during the evaluation. This transparency is key for the CRED method and helps inform how the study might be used despite its limitations [17].

| Tool/Resource Name | Function in Ecotoxicology Research |

|---|---|

| CRED Evaluation Method | Provides the primary checklist of 20 reliability and 13 relevance criteria for evaluating aquatic ecotoxicity studies [17]. |

| CRED Reporting Recommendations | A set of 50 recommendations across six classes to help researchers report all critical study details prospectively, ensuring future reliability and relevance [17]. |

| SciRAP Reporting Checklists | Excel-based checklists for reporting ecotoxicity and other study types, aiding in structured and transparent study documentation [18]. |

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | The world's largest curated database of ecotoxicity data, using systematic review procedures to identify and compile single-chemical toxicity data for ecological species [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My ecotoxicity study was not conducted under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP). Can it still be rated as "Reliable without restrictions" using the CRED checklist?

Yes, absolutely. A key advantage of the CRED method over the older Klimisch approach is that it does not automatically favor GLP studies. A non-GLP study can achieve a high-reliability rating if it demonstrates high scientific quality by comprehensively fulfilling the 20 reliability criteria related to experimental design, execution, and reporting. CRED focuses on scientific rigor and transparent reporting rather than the formal GLP compliance framework [2].

Q2: How do I handle a situation where my ecotoxicity study is strong but is missing one or two specific details listed in the CRED criteria?

The CRED method is designed to be pragmatic. The first step is to document the missing information clearly in your evaluation summary. The impact of the missing detail on the overall assessment depends on its critical nature. If the missing information is minor and does not affect the interpretation of the results or the study's relevance to the assessment context, the study might still be categorized as "Reliable with restrictions." The limitations then become part of the transparent record, allowing risk assessors to understand the constraints while potentially still using the valuable data [17].

Q3: Is the CRED checklist only relevant for regulatory submissions to agencies like the EPA or ECHA?

While CRED is extremely valuable for meeting regulatory requirements and increasing the likelihood that your study will be accepted in regulatory dossiers, its utility is much broader. Using the CRED checklist and its accompanying reporting recommendations enhances the overall quality, transparency, and reproducibility of ecotoxicity research. This makes your published work more trustworthy and useful for other scientists, systematic reviewers, and for inclusion in authoritative databases like the ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase [3] [17].

Q4: The CRED method was developed for aquatic ecotoxicity. Are there similar frameworks for other areas, like environmental exposure data?

Yes, the principles of CRED have inspired the development of analogous frameworks for other data types. The Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating Environmental Exposure Data (CREED) is a direct extension for evaluating the reliability and relevance of environmental monitoring datasets. CREED uses 19 reliability and 11 relevance criteria, following a similar structured and transparent philosophy to improve the usability of exposure data in chemical assessments [17].

In ecotoxicology research, the reliability of any study is fundamentally dependent on the quality and precise characterization of the test substances used. Proper characterization of the source, purity, chemical identity, and formulation of a test substance is not merely a procedural step; it is a core scientific and regulatory requirement that forms the basis for reproducible, interpretable, and defensible ecotoxicity data. Establishing minimum reporting requirements for these parameters ensures that data can be adequately evaluated and utilized in environmental risk assessments [2].

The regulatory evaluation of ecotoxicity studies, often using frameworks like the Klimisch method or the more recent Criteria for Reporting and Evaluating ecotoxicity Data (CRED), heavily depends on the transparency and completeness of test substance information [2]. Inconsistent or insufficient reporting can lead to studies being categorized as "not reliable" or "not assignable," potentially excluding valuable data from risk assessments and introducing uncertainty into regulatory decisions [2]. This technical support guide provides detailed protocols and troubleshooting advice to help researchers overcome common challenges in test substance characterization, thereby supporting the generation of high-quality, reliable ecotoxicological data.

Core Principles and Regulatory Framework

Fundamental Characterization Parameters

Before embarking on any ecotoxicological study, a set of fundamental parameters for the test, control, and reference substances must be established. Regulatory guidelines mandate that these characteristics are determined for each batch and documented prior to use in a study [19] [20]. The key parameters are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental Characterization Parameters for Test Substances

| Parameter | Description | Regulatory Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | Unique identifier such as chemical name and Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) number. | 40 CFR 160.105(a) [19] |

| Strength | Potency or concentration of the active substance. | 40 CFR 160.105(a) [19] |

| Purity | Proportion of the primary substance within the batch, often referring to the percentage of active ingredient. | 40 CFR 160.105(a) [19] |

| Composition | Quantitative description of all constituents, including impurities and additives. | 40 CFR 160.105(a) [19] |

| Solubility | The ability of the substance to dissolve in a solvent relevant to the study (e.g., water, vehicle). | 40 CFR 160.105(b) [19] |

| Stability | The chemical and physical integrity of the substance under specific storage conditions over time. | 40 CFR 160.105(b) [19] |

Documentation and Labeling Requirements

Proper documentation and labeling are critical for traceability and sample integrity throughout the study lifecycle.

- Documentation: Methods used for the synthesis, fabrication, or derivation of the test substance must be thoroughly documented by the sponsor or testing facility [19] [21]. A Certificate of Analysis (C of A) is a standard document that provides detailed data on identity, strength, purity, and composition [21].

- Labeling: Each storage container must be labeled with a unique identifier, which should include the name, CAS or code number, batch number, expiration date (if applicable), and necessary storage conditions [19] [20].

- Retention Samples: For studies longer than four weeks, reserve samples from each batch must be retained for a specified period to allow for future analysis if needed [19] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Analytical Techniques for Characterization

A range of analytical techniques is employed to determine the characteristics of a test substance. The choice of technique depends on the nature of the substance (e.g., organic, inorganic, nanomaterial) and the specific parameter being measured.

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Substance Characterization

| Technique | Acronym | Primary Function in Characterization | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | |||

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography | HPLC | Separates components in a mixture to assess purity and composition. | Purity analysis, related substances, assay [22] [23]. |

| Gas Chromatography | GC | Separates volatile components without decomposition. | Purity and composition analysis for volatile substances [23]. |

| Liquid / Gas Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS, GC-MS | Identifies and quantifies components based on mass and fragmentation patterns. | Molecular weight confirmation, impurity profiling, identification of unknowns [24]. |

| Spectroscopy | |||

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance | NMR | Elucidates molecular structure and confirms chemical identity. | Structural confirmation and identity [24] [23]. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | FTIR | Identifies functional groups within a molecule; provides a fingerprint. | Identity confirmation, polymorph screening [24] [25]. |

| Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy | UV/VIS | Determines characteristic absorption patterns for identification and quantification. | Qualitative and quantitative analysis, molar extinction coefficient [24]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | MS | Determines molecular weight and provides structural information. | Identity confirmation, accurate mass [24]. |

| Elemental Analysis | CHN | Determines the mass fraction of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Nitrogen. | Elemental composition [24]. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry | ICP-MS | Quantifies trace levels of metals and other elements. | Metals testing, impurity profiling [24]. |

| Solid-State Characterization | |||

| X-Ray Powder Diffraction | XRPD | Identifies crystalline structure, polymorphs, and degree of crystallinity. | Polymorph screening, quantification of crystallinity/amorphicity [24] [25]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry | DSC | Measures thermal transitions (e.g., melting point, glass transition). | Polymorph identification, stability studies [24] [25]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis | TGA | Measures mass change as a function of temperature (e.g., solvent loss, decomposition). | Determination of hydrate/solvate content, stability [24] [25]. |

| Dynamic Vapor Sorption | DVS | Measures hygroscopicity and water uptake/loss. | Understanding stability under different humidity conditions [24]. |

| Lucidenic acid O | Lucidenic acid O, MF:C27H40O7, MW:476.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Sulphostin | Sulphostin|DPP4/8/9 Covalent Inhibitor | Bench Chemicals |

Figure 1: The characterization workflow illustrates the key parameters (green) and the primary analytical techniques (blue) used for a comprehensive profile.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the minimum characterization required for a test substance in an ecotoxicology study compliant with Good Laboratory Practice (GLP)?

For a GLP-compliant study, the minimum characterization, as defined by regulations such as 40 CFR 160.105, includes determining and documenting the identity, strength, purity, and composition for each batch of the test substance before its use in a study [19] [20]. Furthermore, when relevant to the study, solubility and the stability of the substance in the vehicle and/or dosing formulation under the conditions of use must be determined [19] [21]. This data is typically consolidated in a Certificate of Analysis (C of A).

FAQ 2: How do I characterize a test substance for a REACH registration dossier?

REACH substance identification requires building a robust substance identity profile. This involves using appropriate analytical data to confirm the molecular structure and composition. ECHA recommends a combination of techniques, including:

- Spectroscopic methods like UV, IR, NMR, and MS to confirm the molecular structure [23].

- Chromatographic methods like HPLC or GC to confirm the purity and composition of the main constituent and any impurities [23]. For inorganic substances, techniques like ICP-MS, ICP-OES, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) are typically applied [23].

FAQ 3: What are the common solid-state forms of a drug substance, and why do they matter?

Many Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) can exist in multiple solid-state forms, which can significantly impact solubility, stability, and bioavailability [25]. The key forms include:

- Polymorphs: Different crystalline forms of the same chemical compound. The most stable polymorph is typically developed to avoid conversion to a less soluble form later, as famously occurred with the drug ritonavir [25].

- Hydrates/Solvates: Crystal forms that incorporate water or solvent molecules into their structure. Their formation and stability can be influenced by humidity and processing conditions [25].

- Amorphous: A non-crystalline form that often has higher solubility but is inherently less stable and prone to crystallization [25].

- Salts and Co-crystals: Engineered forms to improve properties like solubility and stability [25]. Characterization techniques like XRPD, DSC, and TGA are essential for identifying and monitoring these forms [24] [25].

FAQ 4: Our test results are inconsistent between batches. Could the source or purity of the test substance be the cause?

Yes. Inconsistent results are a classic symptom of variability in the test substance. To troubleshoot:

- Audit the Source: Verify if different batches were sourced from the same supplier. Different synthesis routes can lead to different impurity profiles.

- Check the C of A: Compare the Certificates of Analysis for all batches used. Look for variations in purity, impurity profiles, and water/solvent content.

- Analyze Retention Samples: Use techniques like HPLC and XRPD to analyze retained samples from each batch to confirm identity, purity, and solid-state form consistency [22] [25].

- Re-test Stability: The substance may have degraded during storage if stability under test site conditions was not fully established [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Test Substance Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution | Preventive Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor solubility in the vehicle | Incorrect vehicle selection; incorrect pH; solid-form issues (e.g., stable polymorph). | - Determine solubility in a range of vehicles/buffers.- For ionizable compounds, measure pKa and profile solubility vs. pH.- Investigate alternative solid forms (e.g., salt, amorphous). | Conduct pre-study solubility and pKa profiling [19] [25]. Perform solid-form screening early in development. |

| Precipitation in dosing formulation | Instability in the vehicle over time; temperature-induced precipitation. | - Conduct short-term stability of the formulation at the temperature of use.- Use a stabilizing agent (e.g., surfactant). | Determine formulation stability concomitantly with the study per written SOPs [19] [22]. |

| Falling purity during the study | Chemical degradation under storage conditions (hydrolysis, oxidation, photolysis). | - Re-analyze the test substance and a retained sample.- Confirm storage conditions (e.g., temperature, light, humidity). | Determine stability under storage conditions at the test site before the study [19]. Use appropriate packaging and controls. |

| Unexpected toxicity or lack of efficacy | Impurity profile; incorrect chemical identity; polymorphism. | - Re-confirm identity and purity (NMR, HPLC).- Characterize solid form (XRPD).- Analyze for new degradation products. | Fully characterize the impurity profile and solid form of the batch before study initiation [23] [25]. |

| Inconsistent analytical results | Lack of method validation; inhomogeneous test substance. | - Validate the analytical method (specificity, accuracy, precision).- Ensure proper mixing and sampling of the bulk substance. | Perform analytical method validation prior to characterization [22]. |

Figure 2: A logical troubleshooting pathway for resolving inconsistent experimental results by systematically investigating the test substance.

Minimum Reporting Requirements for Ecotoxicology Studies

To ensure that ecotoxicity studies can be properly evaluated and used in regulatory assessments, researchers must transparently report key information about the test substance. The CRED evaluation method emphasizes detailed and transparent reporting to reduce reliance on expert judgment and improve consistency [2]. The following table outlines the minimum information that should be included in any ecotoxicology study report or publication.

Table 4: Minimum Reporting Requirements for Test Substance in Ecotoxicology

| Information Category | Specific Data to Report | Importance for Reliability/Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Source & Identity | - Supplier name and location.- Chemical name(s) and CAS number(s).- Batch or lot number. | Ensures traceability and allows for verification. Critical for evaluating study reliability [2]. |

| Purity & Composition | - Stated purity (e.g., 98.5%).- Identity and approximate concentration of major impurities. | Impurities can influence toxicity. Knowing purity is essential for dose/response accuracy. |

| Characterization Methods | - Brief description of analytical methods used for identification and purity assessment (e.g., "HPLC-UV for purity", "NMR for identity"). | Provides evidence that the substance was properly characterized, supporting data reliability [2] [23]. |

| Formulation Details | - For diluted/dosed formulations: full composition including all solvents, emulsifiers, etc.- Concentration of test substance in the formulation.- Method of preparation. | Allows for accurate replication of the study. Vehicles can affect bioavailability and toxicity. |