LD50, LC50, and NOAEL: A Comprehensive Guide to Key Toxicity Measures for Drug Development

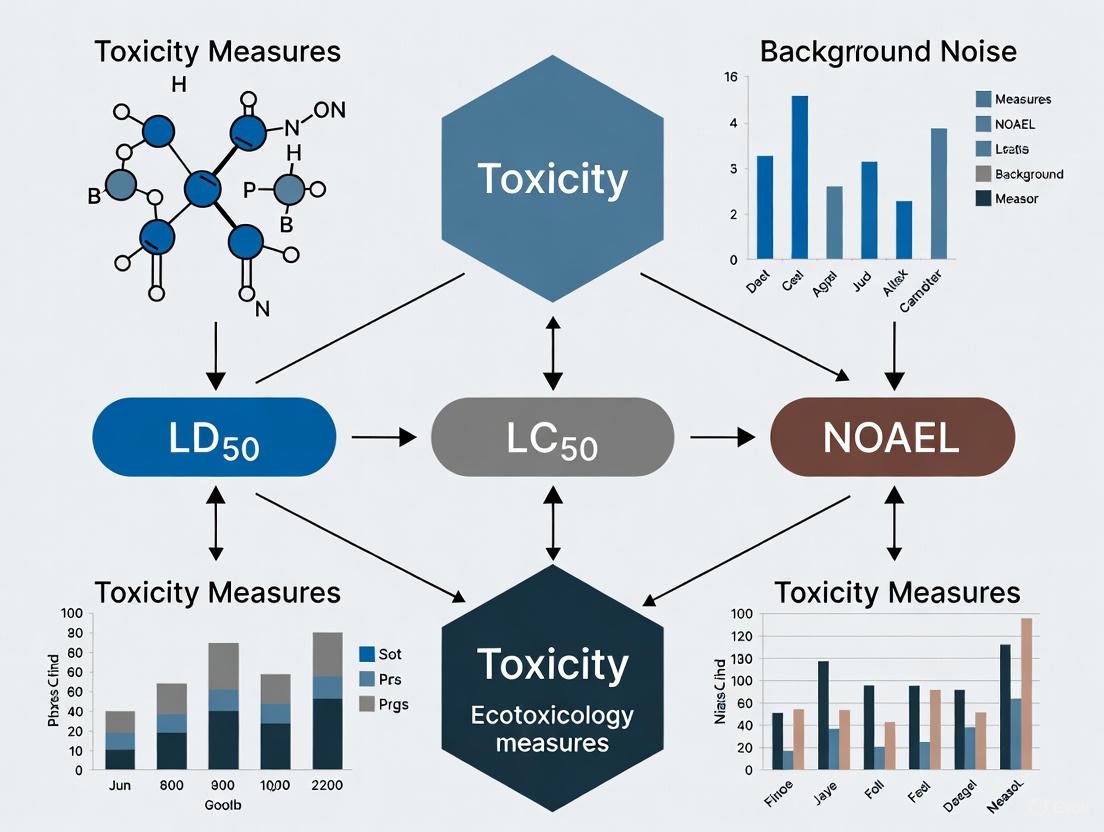

This article provides a thorough exploration of fundamental toxicity measures—LD50, LC50, and NOAEL—essential for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and toxicology.

LD50, LC50, and NOAEL: A Comprehensive Guide to Key Toxicity Measures for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of fundamental toxicity measures—LD50, LC50, and NOAEL—essential for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and toxicology. It covers the foundational definitions, historical context, and statistical basis of these descriptors, then progresses to methodological aspects including testing protocols, regulatory guidelines, and data interpretation. The content addresses current challenges such as interspecies variability and ethical concerns, highlighting modern troubleshooting approaches like computational QSAR models and in vitro alternatives. Finally, it offers a comparative analysis of these metrics for informed risk assessment, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions in toxicity testing for biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding the Basics: Defining LD50, LC50, and NOAEL in Modern Toxicology

Toxicological dose descriptors are fundamental parameters that quantify the relationship between the exposure dose of a chemical substance and the magnitude of its biological effect [1]. These descriptors form the cornerstone of hazard identification, risk assessment, and regulatory decision-making in toxicology. They provide a standardized methodology for comparing toxicity across different chemical entities, establishing safety thresholds, and communicating hazard potential to researchers, regulators, and the public. The development and proper application of these descriptors enable scientists to derive no-effect threshold levels for human health, such as the Derived No-Effect Level (DNEL) or Reference Dose (RfD), and for the environment, known as the Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC) [1].

The science of toxicology operates on the principle that the dose determines the poison, a concept credited to Paracelsus. Modern toxicology has evolved this principle into sophisticated quantitative relationships described by dose-response curves. Dose descriptors represent specific points on these curves, allowing for the objective characterization of toxicological properties. For systemic toxicants—chemicals that affect organ function—toxic effects are generally treated as having an identifiable exposure threshold below which no adverse effects are observed in a population [2]. This threshold concept distinguishes the risk assessment of systemic toxicants from that of non-threshold agents like genotoxic carcinogens.

Table 1: Categories of Toxicological Dose Descriptors

| Category | Descriptor Examples | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Lethality | LD50, LC50 | GHS hazard classification, emergency response planning |

| Subchronic/Chronic Toxicity | NOAEL, LOAEL, BMD | Derivation of chronic health-based guidance values (e.g., RfD, ADI) |

| Environmental Toxicity | EC50, NOEC, DT50 | Environmental hazard classification and risk assessment |

| Carcinogenicity | T25, BMD10 | Cancer risk assessment |

Core Definitions and Quantitative Data

Toxicological dose descriptors are stratified based on the nature and duration of the toxic effect they represent. Understanding their precise definitions, units, and applications is essential for accurate risk assessment.

Acute Lethality Descriptors

LD50 (Lethal Dose, 50%): A statistically derived dose that is expected to cause death in 50% of the treated animal population under defined test conditions [1] [3]. This descriptor is typically obtained from acute toxicity studies where animals are exposed to a single dose or multiple doses within 24 hours.

LC50 (Lethal Concentration, 50%): The analogous concentration of a substance in air or water that is expected to cause death in 50% of the test population during a specified exposure period [1]. For inhalation toxicity, air concentrations are used as exposure values, making LC50 the more relevant parameter.

A lower LD50 or LC50 value indicates higher acute toxicity. These values are crucial for Globally Harmonized System (GHS) classification, where substances are categorized into specific hazard classes based on their acute toxicity potential [1].

Threshold Descriptors for Repeated Exposure

NOAEL (No Observed Adverse Effect Level): The highest experimentally tested exposure level at which there are no statistically or biologically significant increases in the frequency or severity of adverse effects between the exposed population and its appropriate control group [1] [2]. Some effects may be produced at this level, but they are not considered adverse or harmful.

LOAEL (Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level): The lowest experimentally tested exposure level at which there are statistically or biologically significant increases in the frequency or severity of adverse effects between the exposed population and its appropriate control group [1].

NOAEL and LOAEL are typically derived from repeated dose toxicity studies (e.g., 28-day, 90-day, or chronic studies) and reproductive toxicity studies. They form the basis for deriving threshold safety levels for human exposure, such as Reference Doses (RfDs) and Occupational Exposure Limits (OELs) [1].

Environmental Toxicity Descriptors

EC50 (Median Effective Concentration): In ecotoxicology, this refers to the concentration of a test substance that results in a 50% reduction in a non-lethal endpoint, such as algal growth (EbC50) or Daphnia immobilization [1]. These are obtained from acute aquatic toxicity studies.

NOEC (No Observed Effect Concentration): The highest concentration in an environmental compartment (water, soil, etc.) below which no unacceptable effects are observed [1]. It is typically obtained from chronic aquatic and terrestrial toxicity studies.

DT50 (Half-Life): The time required for an amount of a compound to be reduced by half through degradation processes in an environmental compartment (water, soil, air, etc.) [1]. This descriptor measures the persistence of a substance and is used in environmental exposure modeling.

Carcinogenicity Descriptors

For chemicals acting as non-threshold carcinogens, where a NOAEL may not be identifiable, different descriptors are employed [1]:

T25: The chronic dose rate estimated to produce tumors in 25% of animals at a specific tissue site after correction for spontaneous incidence, within the test species' lifetime.

BMD10 (Benchmark Dose): A statistically derived dose estimated to produce a predetermined, low incidence of tumors (e.g., 10%) in a specific tissue after correction for spontaneous incidence.

Table 2: Comprehensive Summary of Key Toxicological Dose Descriptors

| Descriptor | Full Name | Definition | Typical Units | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD50 | Lethal Dose, 50% | Dose killing 50% of test population | mg/kg body weight | Acute toxicity classification |

| LC50 | Lethal Concentration, 50% | Concentration killing 50% of test population | mg/L (air/water) | Inhalation/aquatic toxicity |

| NOAEL | No Observed Adverse Effect Level | Highest dose with no significant adverse effects | mg/kg bw/day | Chronic RfD/DNEL derivation |

| LOAEL | Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level | Lowest dose with significant adverse effects | mg/kg bw/day | Used when NOAEL is not established |

| EC50 | Median Effective Concentration | Concentration causing 50% response reduction | mg/L | Environmental hazard assessment |

| NOEC | No Observed Effect Concentration | Highest concentration with no unacceptable effects | mg/L | Chronic environmental risk assessment |

| BMD10 | Benchmark Dose | Dose producing 10% tumor incidence | mg/kg bw/day | Carcinogen risk assessment |

| DT50 | Half-Life | Time for 50% compound degradation | Days | Environmental persistence assessment |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Determining LD50and Acute Toxicity

The determination of LD50 follows standardized test guidelines, such as those established by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The traditional acute oral toxicity test (OECD TG 401) has been largely replaced by more humane methods that use fewer animals, such as the Fixed Dose Procedure (OECD TG 420), the Acute Toxic Class Method (OECD TG 423), and the Up-and-Down Procedure (OECD TG 425) [4].

Experimental Workflow:

- Test Article Preparation: The chemical is characterized for purity, stability, and solubility. An appropriate vehicle (e.g., corn oil, carboxymethyl cellulose) is selected to prepare homogeneous dosing formulations.

- Animal Selection and Acclimation: Healthy young adult rats or mice of a defined strain (typically Sprague-Dawley rats or CD-1 mice) are selected. Animals are acclimated to laboratory conditions for at least 5 days prior to dosing.

- Dose Administration: Animals are fasted overnight prior to dosing. A single dose of the test substance is administered via oral gavage using a stomach tube or a suitable intubation cannula. The dose volume is typically kept constant (e.g., 10 mL/kg), with varying concentrations of the test substance.

- Clinical Observations: Animals are observed individually for signs of toxicity, morbidity, and mortality at least once during the first 30 minutes, periodically during the first 24 hours, and daily thereafter for a total of 14 days. Observations include changes in skin, fur, eyes, mucous membranes, respiratory patterns, circulatory responses, autonomic functions, and somatomotor activity.

- Body Weight and Pathology: Individual body weights are recorded shortly before dosing, weekly, and at the time of death or sacrifice. All animals found dead or sacrificed are subjected to gross necropsy to identify target organs.

- Data Analysis and LD50 Calculation: The LD50 value is calculated using appropriate statistical methods based on the mortality data observed at each dose level. For the Fixed Dose Procedure, the LD50 is estimated from the dose that induces clear signs of toxicity but not mortality.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for acute oral toxicity testing.

Protocol for Establishing NOAEL/LOAEL from Repeated Dose Studies

The NOAEL and LOAEL are typically determined through subchronic (e.g., 90-day) or chronic (e.g., 1-2 year) toxicity studies, following guidelines such as OECD TG 408 (Repeated Dose 90-Day Oral Toxicity Study in Rodents).

Experimental Workflow:

- Study Design: At least three test groups and a control group are used, with a sufficient number of animals (typically 10-20 rodents per sex per group) to allow for meaningful statistical analysis. Dose selection is based on the results of range-finding studies.

- Dose Administration: The test substance is administered daily (7 days per week) for 90 days via the relevant route (oral, dermal, or inhalation). For oral studies, the test substance is often administered via gavage or mixed in the diet.

- In-life Observations: All animals are observed at least twice daily for morbidity and mortality. Detailed clinical observations are conducted at least once weekly. Individual body weights and food consumption are measured weekly.

- Ophthalmological and Clinical Pathology: All animals undergo ophthalmological examination before the study and near the completion of the study. Hematology, clinical chemistry, and urinalysis parameters are evaluated at the end of the study.

- Necropsy and Histopathology: A full necropsy is performed on all animals, including organ weight determination for key organs. A comprehensive set of tissues is preserved and examined microscopically for the control and high-dose groups, and for any target organs identified across all dose groups.

- NOAEL/LOAEL Determination: The NOAEL is identified as the highest dose level at which no statistically or biologically significant adverse effects are observed. The LOAEL is the lowest dose level at which such adverse effects first become apparent.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for repeated dose toxicity testing.

Advanced Concepts and Modern Approaches

Kinetic Maximum Dose (KMD) in Modern Study Design

Traditional dose-setting in toxicology studies has often relied on the concept of Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD), which aims to use the highest dose that an animal can tolerate without succumbing to overt toxicity [5]. However, this approach has significant limitations, as doses at or near the MTD can induce toxic effects secondary to metabolic overload, disregarding fundamental toxicokinetic principles.

The Kinetic Maximum Dose (KMD) represents a scientifically advanced alternative for dose selection [5]. The KMD is defined as the maximum dose at which the test compound's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination (ADME) processes remain unsaturated. Beyond this dose, disproportionate increases in systemic exposure occur, leading to toxicity that may not be relevant to human exposure scenarios.

The determination of KMD incorporates toxicokinetic (TK) studies that measure blood or plasma concentrations of the test compound and its metabolites at various time points after administration. This data is used to calculate key TK parameters such as C~max~ (maximum concentration), T~max~ (time to maximum concentration), and AUC (area under the concentration-time curve). The dose at which these parameters begin to increase disproportionately indicates saturation of clearance mechanisms and defines the KMD.

Computational Toxicology and Machine Learning Approaches

Modern toxicology is increasingly leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to predict toxicological dose descriptors, thereby reducing reliance on animal testing [4] [6] [7]. These computational approaches align with the global movement toward New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and the 3Rs principle (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in animal research.

Machine Learning Models for Acute Toxicity Prediction:

- Data Sources: Large-scale toxicity databases such as TOXRIC (containing over 80,000 unique compounds and 122,594 toxicity measurements) and the EPA's ToxCast program provide extensive data for model training [6] [7].

- Algorithm Development: Models employ various algorithms including random forest, support vector machines, neural networks, and graph convolution networks to establish relationships between chemical structure and toxicological endpoints.

- Model Performance: The Collaborative Acute Toxicity Modeling Suite (CATMoS) represents a consensus approach that leverages multiple models, demonstrating high accuracy and robustness comparable to animal studies for predicting LD50 values [4].

- Recent Advances: The ToxACoL (Adjoint Correlation Learning) paradigm represents a significant advancement by modeling relationships between multiple toxicity endpoints, enabling knowledge transfer from data-rich to data-scarce endpoints and improving prediction accuracy for human-relevant toxicity by 43-87% [7].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for Toxicological Dose Assessment

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in Dose Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Rodent Models (Rat/Mouse) | In Vivo System | Primary test species for determining LD50, NOAEL, and LOAEL in standardized studies |

| In Vitro Toxicity Assays | Alternative Method | High-throughput screening for mechanistic toxicity, supporting 3Rs principles |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Analytical Instrument | Quantification of test compound and metabolites in toxicokinetic studies for KMD determination |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling | Computational Tool | Predicts tissue dosimetry and extrapolates toxicity across species and exposure scenarios |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Computational Tool | Predicts toxicity endpoints from chemical structure, reducing animal testing needs |

| Clinical Pathology Analyzers | Diagnostic Tool | Automated analysis of hematological and clinical chemistry parameters for NOAEL determination |

| Histopathology Equipment | Diagnostic Tool | Tissue processing, staining, and microscopic examination for identifying adverse effects |

Applications in Risk Assessment and Regulatory Science

Toxicological dose descriptors are not merely academic concepts; they serve as critical inputs for chemical risk assessment and the derivation of human health-based guidance values. The process of converting experimental dose descriptors to protective human exposure limits involves several key steps and uncertainty factors.

The Reference Dose (RfD) is derived by dividing the NOAEL (or LOAEL) from the most sensitive relevant species by composite Uncertainty Factors (UFs) and a Modifying Factor (MF) [2]:

RfD = NOAEL / (UFH × UFA × UFS × UFL × MF)

Where:

- UFH = Uncertainty factor for interspecies (animal-to-human) differences (typically 10)

- UFA = Uncertainty factor for intraspecies (human-to-human) variability (typically 10)

- UFS = Uncertainty factor for subchronic-to-chronic extrapolation

- UFL = Uncertainty factor for LOAEL-to-NOAEL extrapolation

- MF = Modifying factor for additional uncertainties (typically 1-10)

This approach ensures that the derived RfD is protective of sensitive human subpopulations, including children, the elderly, and individuals with pre-existing health conditions. The RfD represents a daily exposure level that is likely to be without an appreciable risk of deleterious effects over a lifetime [2].

For environmental risk assessment, the Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC) is derived by applying assessment factors to the most sensitive ecotoxicological descriptor (e.g., EC50 or NOEC) from base-set organisms representing different trophic levels (algae, Daphnia, and fish) [1].

The evolution of toxicological dose descriptors continues with the integration of mechanistic data, high-throughput in vitro screening, and sophisticated computational models. These advancements promise more human-relevant risk assessments while reducing the reliance on traditional animal testing. As toxicology moves toward a more pathway-based understanding of toxicity, the fundamental dose descriptors described in this document will continue to serve as the quantitative foundation for chemical safety assessment and regulatory decision-making.

The Median Lethal Dose (LD50) represents a foundational concept in toxicology, defined as the dose of a substance required to kill 50% of a test population under standardized conditions [8] [9]. Developed by J.W. Trevan in 1927, this metric was originally designed to standardize the potency of biologically derived medicines like digitalis and insulin [10] [11]. Its introduction provided a statistically robust method for comparing the acute toxicity of different substances, establishing a reproducible benchmark that avoided the extremes of minimal or absolute lethality [3].

For decades, LD50 testing became a global standard, incorporated into regulatory guidelines worldwide for pharmaceutical, industrial chemical, and agrochemical safety assessment [12]. However, its widespread application also generated significant controversy regarding animal welfare, scientific relevance, and reproducibility [10] [11]. This comprehensive review examines the historical context of Trevan's innovation, its methodological evolution, the criticisms that shaped its modern application, and the advanced alternatives currently transforming acute toxicity assessment.

The Trevan Era: Origins and Initial Methodology

Historical Context and Scientific Need

Prior to Trevan's work, toxicity testing lacked standardization. Methods for evaluating drug potency were highly variable, making it difficult to compare results between laboratories or establish consistent dosing for therapeutic agents [10]. Biological products like diphtheria antitoxin exhibited natural variation between batches, necessitating a reliable method to standardize their strength [11]. Trevan's seminal 1927 paper, "The Error of Determination of Toxicity," addressed this need by introducing a statistically rigorous approach to lethality testing [10].

The innovation centered on using death as a universal endpoint, enabling comparisons between chemicals with different mechanisms of action [9]. The 50% mortality rate was selected because it represented the point of maximum sensitivity in a population response, where statistical variation was minimized compared to extreme endpoints like LD01 or LD99 [3]. This methodological breakthrough coincided with increasing regulatory oversight of pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals, creating demand for standardized safety assessment protocols [12].

Original Experimental Protocol

Trevan's classical LD50 determination involved several meticulous steps:

- Test population: Homogeneous groups of laboratory animals, typically rats or mice, of similar age, weight, and genetic background [12]

- Dose administration: Substances administered via oral, dermal, or inhalation routes with precise control of dosage [9]

- Observation period: Monitoring for 14 days post-administration to account for delayed effects [11]

- Data analysis: Plotting dose-response curves and calculating the precise dose causing 50% mortality using statistical methods [10]

The original process required significant numbers of animals to achieve statistical precision, with early tests sometimes using 60-100 animals per substance [11]. The results were expressed as mass of substance per unit body mass (typically mg/kg), enabling direct comparison between different chemicals and test systems [9].

Evolution of Methodological Approaches

Refinements in Statistical Methodology

Following Trevan's initial work, several researchers developed more efficient statistical approaches for LD50 determination:

Table 1: Evolution of LD50 Statistical Methods

| Method | Developer(s) | Year | Key Innovation | Animal Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical LD50 | J.W. Trevan | 1927 | Original dose-mortality curve analysis | High (60-100 animals) |

| Karber's Method | G. Karber | 1931 | Simplified arithmetic calculation | Moderate |

| Probit Analysis | D. Finney | 1952 | Statistical transformation of dose-response data | Moderate |

| Litchfield & Wilcoxon | J.T. Litchfield & F. Wilcoxon | 1949 | Graphical nomogram method for estimation | Reduced |

| Up-and-Down Procedure | W.J. Dixon & A.M. Mood | 1948 | Sequential dosing minimizing animals | Significant reduction |

| Fixed Dose Procedure | OECD | 1992 | Non-lethal endpoints, toxicity classification | Minimal |

Probit analysis, developed by Finney, transformed mortality percentages into probability units ("probits") that exhibited a linear relationship with logarithm of dose, enabling more precise LD50 calculation with confidence limits [10]. The Litchfield and Wilcoxon method provided a simplified graphical approach that gained widespread adoption in industrial toxicology laboratories due to its practicality without complex calculations [10] [12].

These methodological refinements progressively reduced animal requirements while improving the statistical reliability of acute toxicity assessments [12].

Regulatory Adoption and Standardization

The LD50 test was incorporated into numerous international regulatory frameworks, including:

- OECD Guidelines for Chemical Testing (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development)

- EPA Toxic Substances Control Act (United States Environmental Protection Agency)

- FDA Pharmaceutical Requirements (Food and Drug Administration)

- EEC Directives (European Economic Community) [11]

This regulatory entrenchment occurred despite Trevan's original purpose being specifically for standardizing highly variable biological products rather than all chemical classes [11]. By the 1970s-1980s, LD50 testing had become a standardized requirement for product classification and labeling under emerging systems like the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) [13].

Criticisms and Limitations

Scientific Limitations

Research conducted in the decades following Trevan's work revealed substantial limitations in the LD50 concept:

- Inter-species Variability: LD50 values show poor correlation between species, undermining extrapolation to humans [12] [3]. For example, a compound might be slightly toxic in mice but highly poisonous in rats [11].

- Intra-species Variability: Factors including age, sex, diet, genetic strain, and housing conditions significantly influence results [12] [11]. Seasonal variations and even bedding material can affect outcomes [11].

- Route-dependent Toxicity: Substances exhibit different toxicities based on administration route (oral, dermal, inhalation), making single-route testing insufficient for comprehensive safety assessment [9].

- Poor Predictivity for Human Response: Species-specific metabolic pathways and mechanisms of toxicity limit the human relevance of animal LD50 data [12] [11].

A significant international study in the late 1970s involving 100 laboratories across 13 countries demonstrated marked discrepancies in LD50 results for the same substances despite standardized protocols [11]. This irreproducibility challenged the fundamental premise of LD50 as a "biological constant" [12].

Ethical Concerns

The ethical implications of LD50 testing generated increasing controversy through the 1970s-1980s:

- Animal Suffering: The test caused "appreciable pain" to animals, with observed symptoms including "agonising pain, convulsions, bleeding, diarrhoea, and eventually lingering death over a number of days" [11].

- Mortality Endpoint: Death as a required outcome raised significant welfare concerns among researchers and the public [11].

- Large Scale Use: In 1980 alone, British laboratories used 484,849 animals for LD50 tests [11].

These concerns prompted toxicologists to reconsider whether the scientific value justified the ethical costs, particularly for substances with low toxicity potential [12] [11].

Modern Applications and Alternative Approaches

Contemporary Use in Regulatory Science

Despite limitations, LD50 remains embedded in chemical classification and labeling systems:

Table 2: GHS Classification System Based on LD50 Values

| GHS Category | Oral LD50 (mg/kg) | Dermal LD50 (mg/kg) | Inhalation LC50 (mg/L) | Hazard Statement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≤5 | ≤50 | ≤0.1 | Fatal if swallowed/ in contact with skin/ if inhaled |

| 2 | 5-50 | 50-200 | 0.1-0.5 | Fatal if swallowed/ in contact with skin/ if inhaled |

| 3 | 50-300 | 200-1000 | 0.5-2.5 | Toxic if swallowed/ in contact with skin/ if inhaled |

| 4 | 300-2000 | 1000-2000 | 2.5-5 | Harmful if swallowed/ in contact with skin/ if inhaled |

| 5 | 2000-5000 | 2000-5000 | 5-20 | May be harmful if swallowed/ in contact with skin/ if inhaled |

The Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TOC) approach has been developed for chemicals with limited toxicity data, using LD50 values within a framework of conservative safety factors to establish health-protective exposure levels [13]. This application represents a shift from precise lethality determination to hazard characterization and risk-based assessment [13].

Alternative Methods and the 3Rs Principle

Modern toxicology has embraced alternative approaches aligned with the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement):

- In vitro systems: Cell culture models using human cells provide species-relevant toxicity data without whole animals [14] [11]. The FDA approved alternative methods to LD50 for testing Botox in 2011 [8] [3].

- In silico approaches: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models predict toxicity based on chemical structure [14]. Computational tools like the EPA's TEST software can estimate LD50 values without animal testing [14].

- Tiered testing strategies: Simplified initial assessments (e.g., Fixed Dose Procedure) reduce animal use by 70-80% compared to classical LD50 [12].

- Integrated testing strategies: Combining acute toxicity assessment with other toxicological evaluations to maximize information from minimal testing [12].

These innovations reflect a paradigm shift from lethality quantification to comprehensive toxicity characterization, emphasizing mechanism of action, target organ identification, and human relevance [12] [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Table 3: Research Toolkit for Acute Toxicity Assessment

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in Toxicity Assessment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Rodents | In vivo model for acute systemic toxicity | Classical LD50 determination (now reduced) |

| Cell Culture Systems | In vitro models for cytotoxicity assessment | Human-relevant preliminary screening |

| Chemical Standards | Reference compounds for assay validation | Quality control and inter-laboratory comparison |

| QSAR Software | Computer-based toxicity prediction | Priority setting and screening before animal testing |

| Clinical Chemistry Analyzers | Measure biochemical parameters in blood/tissues | Identification of target organ toxicity |

| Histopathology Equipment | Tissue processing and microscopic examination | Morphological analysis of toxic effects |

| Analytical Chemistry Instruments | Quantify compound concentration and metabolites | Exposure verification and pharmacokinetic analysis |

The evolution of LD50 from Trevan's 1927 innovation to contemporary applications illustrates the dynamic nature of toxicological science. While the concept remains historically significant and embedded in classification systems, its practical application has been substantially transformed. Modern approaches emphasize mechanistic understanding, human relevance, and ethical responsibility, moving beyond the simple quantification of lethality that defined earlier toxicology.

The continued development of novel alternative methods – particularly in silico and in vitro systems – promises to further revolutionize acute toxicity assessment while addressing scientific and ethical limitations of traditional approaches. This evolution reflects toxicology's ongoing maturation from a descriptive to a predictive science, better positioned to protect human health while respecting ethical boundaries in research methodology.

In toxicological risk assessment, LD50 (Lethal Dose 50%) and LC50 (Lethal Concentration 50%) represent fundamental parameters for quantifying acute toxicity. While both metrics measure the potency of chemical substances required to cause 50% mortality in a test population, they differ critically in their application and exposure context. LD50 refers to the dose administered via oral, dermal, or injection routes, while LC50 applies to airborne concentrations or aquatic exposure environments. This whitepaper delineates the scientific distinctions, methodological frameworks, and regulatory applications of these parameters within a comprehensive toxicity assessment paradigm that includes NOAEL (No Observed Adverse Effect Level) for establishing safety thresholds. Through detailed protocols, data comparison, and emerging computational approaches, we provide drug development professionals with the necessary toolkit for informed toxicological evaluation and decision-making.

Acute toxicity refers to the ability of a substance to cause adverse effects relatively soon after a single administration or short-term exposure (minutes up to approximately 24-48 hours) [9]. The median lethal dose (LD50) is defined as the dose of a substance that causes death in 50% of a test animal population under standardized conditions, while the median lethal concentration (LC50) represents the concentration of a substance in air (or water) that causes death in 50% of the test population during a specified exposure period [3] [9] [15]. These values are statistically derived and provide a standardized basis for comparing the intrinsic acute toxicity of different chemical entities.

The LD50 concept was first introduced by J.W. Trevan in 1927 to estimate the relative poisoning potency of drugs and medicines, using death as a standardized endpoint to enable comparisons between chemicals with different mechanisms of action [3] [9]. These parameters have since become cornerstones of regulatory toxicology, serving as critical inputs for GHS hazard classification, safety data sheets, and risk assessment models across pharmaceutical, chemical, and environmental sectors [15].

Defining LD50: Lethal Dose 50%

Core Definition and Measurement

LD50 represents a statistically derived single dose that causes death in 50% of exposed animals within a specified observation period [3] [16]. The value is typically normalized to body weight and expressed as milligrams of substance per kilogram of body weight (mg/kg) [3]. This normalization enables comparison of toxicity across species of different sizes, though toxicity does not always scale linearly with body mass [3].

The choice of 50% lethality as a benchmark reduces the amount of testing required compared to measuring extremes (e.g., LD01 or LD99) while providing a statistically robust measure of central tendency [3]. However, it is crucial to recognize that LD50 does not represent an absolute threshold; some individuals may be killed by much lower doses (hypersensitive), while others may survive doses significantly higher than the LD50 (resistant) [3].

Routes of Administration

LD50 values must always be qualified by the route of administration, as toxicity can vary significantly depending on how a substance enters the body [3] [9]:

- Oral (PO): Administration through the mouth, relevant for food, drugs, and accidental ingestion

- Dermal (skin): Application on the skin, important for occupational exposure scenarios

- Intravenous (IV): Injection into veins, typically showing highest immediate toxicity

- Intraperitoneal (IP): Injection into the abdominal cavity

- Intramuscular (IM): Injection into muscle tissue

- Subcutaneous (SC): Injection beneath the skin

The same compound can have dramatically different LD50 values depending on the administration route due to differences in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [9]. For example, dichlorvos shows an oral LD50 in rats of 56 mg/kg but an intraperitoneal LD50 of 15 mg/kg, demonstrating significantly higher toxicity when introduced directly into the abdominal cavity [9].

Defining LC50: Lethal Concentration 50%

Core Definition and Measurement

LC50 represents the concentration of a chemical in air (or water) that causes death in 50% of test animals during a specified exposure period [9] [15]. For airborne substances, LC50 is typically expressed as parts per million (ppm) or milligrams per cubic meter (mg/m³) [9]. In environmental contexts, particularly aquatic toxicology, LC50 refers to the concentration in water (mg/L) that is lethal to 50% of test organisms over a defined period, commonly 96 hours for fish [4] [17].

The exposure duration is a critical parameter for LC50 values and must always be specified [9]. Standard inhalation toxicity tests typically employ a 4-hour exposure period followed by clinical observation for up to 14 days [9]. The LC50 value is then derived from the concentration that proves lethal to half the animals during this observation window [9].

Haber's Law and Time-Concentration Relationships

The concept of LC50 incorporates the relationship between concentration and exposure time, often expressed through Ct products (concentration × time) [3]. This relationship, sometimes referred to as Haber's Law, assumes that exposure to 1 minute of 100 mg/m³ is equivalent to 10 minutes of 10 mg/m³ [3]. However, this relationship does not hold for all chemicals, particularly those that are rapidly metabolized or detoxified (e.g., hydrogen cyanide) [3]. For such substances, the lethal concentration may be reported as LC50 with qualification of exposure duration without assuming linear time-concentration relationships [3].

Critical Differences Between LD50 and LC50

While both LD50 and LC50 measure acute lethal toxicity, they differ fundamentally in their application, units, and experimental approaches. The table below summarizes these key distinctions:

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between LD50 and LC50

| Parameter | LD50 | LC50 |

|---|---|---|

| What it measures | Dose (amount) of substance | Concentration in exposure medium |

| Primary routes | Oral, dermal, injection | Inhalation, aquatic immersion |

| Typical units | mg/kg body weight | ppm, mg/m³ (air); mg/L (water) |

| Exposure context | Direct administration | Environmental concentration |

| Time specification | Single administration, observation period | Specified exposure duration (e.g., 4-hour, 96-hour) |

| Key variables | Body weight, route of administration | Breathing rate (inhalation), water temperature (aquatic) |

| Common test species | Rats, mice | Rats (inhalation); Fish, daphnia (aquatic) |

The most appropriate parameter depends on the anticipated exposure scenario. LD50 is most relevant for pharmaceutical dosing, food contaminants, and situations where a specific quantity of material is ingested or applied to the skin. LC50 is more applicable for occupational exposure to airborne chemicals, environmental contamination, and aquatic toxicology [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

LD50 Testing Protocol

Traditional LD50 determination follows established guidelines from organizations such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [4]:

- Test System Selection: Healthy young adult animals (typically rats or mice) of both sexes are acclimatized to laboratory conditions [9].

- Dose Administration:

- For oral administration, substances are administered via gavage in a single dose

- For dermal administration, substances are applied to shaved skin for a fixed period (typically 24 hours)

- Animals are fasted prior to oral administration (typically 16-18 hours) to ensure uniform absorption

- Observation Period: Animals are clinically observed for up to 14 days after administration, recording all signs of toxicity, morbidity, and mortality [9].

- Dose-Response Analysis: Multiple dose groups are tested to establish a mortality range from 0% to 100%, with the LD50 calculated using statistical methods (e.g., probit analysis) from this dose-response data [3].

- Necropsy: Deceased animals undergo gross necropsy to identify target organ toxicity [18].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for LD50 Testing

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Laboratory rodents (rats, mice) | Primary test system for in vivo toxicity assessment |

| Gavage needles | Precise oral administration of test substances |

| Metabolic cages | Individual housing for collection of excreta and monitoring of food/water intake |

| Clinical chemistry analyzers | Assessment of hematological and biochemical parameters |

| Histopathology equipment | Tissue processing, staining, and microscopic examination for organ damage |

| Statistical software | Dose-response analysis and LD50 calculation (e.g., probit analysis) |

LC50 Testing Protocol

Inhalation LC50 testing follows a distinct methodological framework:

- Atmosphere Generation: Test substance is mixed with air at known concentrations in inhalation chambers [9].

- Exposure System: Animals are placed in chambers where they are exposed to the test atmosphere for a fixed period (typically 4 hours) [9].

- Concentration Verification: Chamber atmospheres are analytically monitored throughout exposure to verify concentration consistency [9].

- Post-Exposure Observation: Animals are removed from chambers and clinically observed for up to 14 days [9].

- Concentration-Response Analysis: Multiple concentration groups are tested to establish mortality range, with LC50 calculated using statistical methods [9].

For aquatic toxicity testing (e.g., fish LC50), test organisms are exposed to various concentrations of the test substance in water for a specified period (commonly 96 hours), with mortality recorded at regular intervals [17].

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in selecting and interpreting these acute toxicity measures:

Toxicity Classification and Interpretation

Toxicity Scales and Categorization

LD50 and LC50 values provide a basis for classifying substances according to their acute toxicity potential. Two common classification systems are widely used:

Table 3: Toxicity Classes According to Hodge and Sterner Scale

| Toxicity Rating | Commonly Used Term | Oral LD50 (rats) mg/kg | Inhalation LC50 (rats, 4hr) ppm | Dermal LD50 (rabbits) mg/kg | Probable Lethal Dose for Man |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extremely Toxic | 1 or less | 10 or less | 5 or less | 1 grain (a taste, a drop) |

| 2 | Highly Toxic | 1-50 | 10-100 | 5-43 | 4 ml (1 tsp) |

| 3 | Moderately Toxic | 50-500 | 100-1000 | 44-340 | 30 ml (1 fl. oz.) |

| 4 | Slightly Toxic | 500-5000 | 1000-10,000 | 350-2810 | 600 ml (1 pint) |

| 5 | Practically Non-toxic | 5000-15,000 | 10,000-100,000 | 2820-22,590 | 1 litre (or 1 quart) |

| 6 | Relatively Harmless | 15,000 or more | 100,000 | 22,600 or more | 1 litre (or 1 quart) |

Table 4: Toxicity Classes According to Gosselin, Smith and Hodge

| Toxicity Rating or Class | Dose | For 70-kg Person (150 lbs) |

|---|---|---|

| 6 Super Toxic | Less than 5 mg/kg | 1 grain (a taste – less than 7 drops) |

| 5 Extremely Toxic | 5-50 mg/kg | 4 ml (between 7 drops and 1 tsp) |

| 4 Very Toxic | 50-500 mg/kg | 30 ml (between 1 tsp and 1 fl. oz.) |

| 3 Moderately Toxic | 500-5000 mg/kg | 30-600 ml (between 1 fl. oz. and 1 pint) |

| 2 Slightly Toxic | 5-15 g/kg | 600-1200 ml (1 pint to 1 quart) |

| 1 Practically Non-Toxic | Above 15 g/kg | More than 1 quart |

It is essential to note which scale is being referenced when classifying compounds, as the same LD50 value may receive different ratings across systems [9]. For example, a chemical with an oral LD50 of 2 mg/kg would be rated as "1" and "highly toxic" according to Hodge and Sterner but rated as "6" and "super toxic" according to Gosselin, Smith and Hodge [9].

Comparative Toxicity Examples

The following table provides representative LD50 values for common substances, illustrating the wide range of acute toxicity:

Table 5: Comparative LD50 Values for Selected Substances

| Substance | Animal, Route | LD50 (mg/kg) | Toxicity Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Botulinum toxin | Human, estimated oral | 0.000000001 | Super toxic |

| Sarin | Human, estimated | 0.001-0.03 | Super toxic |

| Sodium cyanide | Rat, oral | 6.4 | Extremely toxic |

| Nicotine | Rat, oral | 50 | Highly toxic |

| Caffeine | Rat, oral | 192 | Moderately toxic |

| Aspirin | Rat, oral | 1,600 | Slightly toxic |

| Ethanol | Rat, oral | 7,060 | Slightly toxic |

| Table salt | Rat, oral | 3,000 | Slightly toxic |

| Vitamin C | Rat, oral | 11,900 | Practically non-toxic |

| Water | Rat, oral | >90,000 | Relatively harmless |

Integration with Other Toxicity Measures: NOAEL and Beyond

NOAEL in Toxicological Assessment

While LD50 and LC50 measure acute lethality, NOAEL (No Observed Adverse Effect Level) represents the highest dose or exposure level at which no statistically or biologically significant adverse effects are observed in treated subjects compared to appropriate controls [18]. NOAEL is typically derived from longer-term repeated dose studies (28-day, 90-day, or chronic toxicity studies) and forms the foundation for establishing safety thresholds in human risk assessment [15] [18].

The relationship between these parameters can be visualized along a typical dose-response curve:

Regulatory Application and Safety Assessment

In regulatory toxicology, NOAEL values from animal studies are used to establish safe starting doses for human clinical trials through the application of safety factors [18]. The Human Equivalent Dose (HED) is calculated using allometric scaling, with typical safety factors of 10-fold for interspecies differences and an additional 10-fold for intraspecies variability, resulting in a 100-fold safety margin for establishing acceptable exposure limits [18].

For pharmaceutical development, the therapeutic index (ratio of LD50 to ED50) provides a more meaningful safety measure than LD50 alone, as it relates toxicity to efficacy [3]. Drugs with a high therapeutic index have a wide margin between effective and toxic doses, while those with a low therapeutic index require careful therapeutic drug monitoring [3].

Modern Approaches and Future Directions

Computational Toxicology and Machine Learning

Traditional LD50/LC50 determination has required significant animal testing, but modern approaches are increasingly leveraging computational methods to reduce animal use while maintaining predictive accuracy [4]. Initiatives such as the Collaborative Acute Toxicity Modeling Suite (CATMoS) utilize machine learning models trained on existing in vivo data to generate consensus predictions for acute oral toxicity [4].

These computational models must comply with OECD guidelines for quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR), requiring [4]:

- A defined endpoint

- An unambiguous algorithm

- A defined domain of applicability

- Appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity

- A mechanistic interpretation, if possible

Machine learning models have demonstrated high performance in separating compounds with undesirable LD50 values (<300 mg/kg) from those with low acute oral toxicity (>2000 mg/kg), enabling prioritization of in vivo testing and significant reduction in animal use [4].

Alternative Testing Strategies

Growing regulatory and ethical pressures are driving development of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) including in vitro systems and computational models [4]. The European Parliament's 2021 vote to phase out animal testing in research and testing underscores the importance of developing validated alternative methods [4].

These approaches include:

- In vitro cytotoxicity assays using human cell lines

- Organs-on-chips and 3D tissue models

- Transcriptomic and proteomic biomarkers of toxicity

- High-throughput screening approaches

While these methods show promise for specific toxicity endpoints, predicting in vivo acute toxicity remains challenging due to complex toxicokinetic factors including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion that cannot be fully captured in simplified in vitro systems [4].

LD50 and LC50 represent complementary yet distinct approaches to quantifying acute toxicity, with LD50 measuring administered dose and LC50 measuring environmental concentration. Both parameters provide critical information for hazard classification, risk assessment, and safety evaluation across pharmaceutical, chemical, and environmental domains. While these measures have historically relied on animal testing, modern toxicology is increasingly embracing computational approaches and novel testing methodologies to reduce animal use while maintaining predictive accuracy. Integration of these acute toxicity measures with subchronic and chronic endpoints such as NOAEL provides a comprehensive framework for safety assessment and risk-based decision making in drug development and chemical safety evaluation. As toxicological science advances, the continued evolution of these paradigms will enhance our ability to predict and manage chemical risks while reducing reliance on traditional animal testing.

Within toxicological risk assessment, the No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (NOAEL) and Lowest-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (LOAEL) represent critical dose-response benchmarks for establishing chemical safety thresholds. This technical guide examines the definition, derivation, and application of NOAEL and LOAEL within the broader context of toxicity measures including LD50 and LC50. We detail standardized experimental protocols for determining these values across study types, analyze quantitative data from representative studies, and present methodological frameworks for translating experimental results into human safety standards. The interfaces between these established assessment tools and emerging approaches such as Benchmark Dose modeling are critically evaluated to provide researchers and drug development professionals with comprehensive methodological guidance grounded in current regulatory practice.

Toxicological dose descriptors are quantitative measures that identify the relationship between a specific effect of a chemical substance and the dose at which it occurs [1]. These parameters form the foundation of hazard identification, risk assessment, and regulatory decision-making for pharmaceuticals, industrial chemicals, and environmental contaminants [1]. In systematic toxicological evaluation, dose descriptors span a continuum from lethal potency indicators (LD50, LC50) to sublethal effect thresholds (NOAEL, LOAEL), each providing distinct insights into chemical hazard profiles.

The No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (NOAEL) is defined as the highest exposure level at which there are no biologically significant increases in the frequency or severity of adverse effects between the exposed population and its appropriate control [19] [1]. Conversely, the Lowest-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (LOAEL) represents the lowest exposure level at which there are biologically significant increases in frequency or severity of adverse effects [19] [1]. These values are typically derived from controlled experimental studies and are essential for establishing threshold-based safety limits for non-carcinogenic effects [20].

Table 1: Fundamental Toxicological Dose Descriptors

| Dose Descriptor | Definition | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| LD50 | Statistically derived dose lethal to 50% of test population | Acute toxicity assessment [1] |

| LC50 | Statistically derived concentration lethal to 50% of test population | Inhalation toxicity assessment [1] |

| NOAEL | Highest dose with no observed adverse effects | Chronic toxicity, risk assessment [19] [1] |

| LOAEL | Lowest dose with observed adverse effects | Chronic toxicity, risk assessment [19] [1] |

| EC50 | Concentration producing 50% of maximal effect | Ecotoxicity, potency assessment [1] |

Experimental Determination of NOAEL and LOAEL

Study Design Considerations

Determination of NOAEL and LOAEL values requires carefully controlled studies designed to characterize the dose-response relationship of test substances. The selection of experimental animal species and strains is of utmost importance, with preference given to models with similarity to humans in metabolic profiles, physiological mechanisms, and therapeutic target characteristics [21]. Standardized testing approaches include:

Repeated Dose Toxicity Studies: These studies constitute the primary source for NOAEL/LOAEL determination and are typically conducted at three dose levels (low, mid, and high) plus a control group [1] [22]. Common protocols include 28-day, 90-day, and chronic (≥12 month) exposures with daily administration of test substance via relevant routes (oral, dermal, or inhalation) [1]. Study designs incorporate comprehensive clinical observations, clinical pathology, gross necropsy, and histopathological examination to detect potential adverse effects [22].

Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity Studies: These specialized assessments evaluate effects on fertility, embryonic development, and postnatal growth [1]. Such studies are particularly sensitive for identifying LOAELs for endocrine-disrupting compounds and developmental toxicants at exposure levels that may not produce maternal toxicity.

Methodological Workflow

The experimental workflow for establishing NOAEL and LOAEL follows a standardized progression from study design through data interpretation:

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for NOAEL/LOAEL Determination

Critical Methodological Elements

Dose Selection and Spacing: Appropriate dose spacing is critical for accurate NOAEL/LOAEL determination. Studies designed with excessively wide dose intervals may identify a LOAEL but fail to establish a true NOAEL, necessitating the application of larger uncertainty factors in risk assessment [21]. Optimal dose spacing reflects judgment on the likely steepness of the dose-response slope, with steeper slopes requiring tighter spacing [21].

Adversity Determination: A fundamental challenge in NOAEL/LOAEL derivation is distinguishing between adverse effects and adaptive, non-adverse responses. According to the U.S. EPA, adverse ecological effects are "changes that are considered undesirable because they alter valued structural or functional characteristics of ecosystems or their components" [23]. This determination considers the type, intensity, and scale of the effect as well as potential for recovery [23].

Statistical Power: Study sensitivity for detecting adverse effects depends on appropriate sample sizes and statistical methods. Underpowered studies may fail to detect statistically significant effects at lower doses, resulting in inflated NOAEL values [24].

Quantitative Data and Comparative Analysis

Experimental data from toxicological studies provide concrete examples of NOAEL and LOAEL values across different substances and test systems:

Table 2: Experimentally Determined NOAEL and LOAEL Values

| Substance | Test System | NOAEL | LOAEL | Critical Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxydemeton-methyl | Rat (90-day) | 0.5 mg/kg/day | 2.3 mg/kg/day | Weight loss, convulsions | [21] |

| Boron | Rat | 55 mg/kg/day | 76 mg/kg/day | Developmental toxicity | [22] |

| Barium | Rat (chronic) | 0.21 mg/kg/day | 0.51 mg/kg/day | Increased blood pressure | [21] |

| Acetaminophen | Human | 25 mg/kg/day | 75 mg/kg/day | Hepatotoxicity | [22] |

The ratio between LOAEL and NOAEL values provides insight into the steepness of the dose-response curve. Analysis of multiple datasets suggests that this ratio is frequently less than 10-fold, reflecting typical experimental dose spacing [21]. This observation has important implications for uncertainty factor application when using LOAEL rather than NOAEL values in risk assessment.

Interrelationship with Other Toxicity Measures

NOAEL and LOAEL exist within a continuum of toxicological dose descriptors that collectively characterize compound hazard. The relationship between these parameters can be visualized within a comprehensive dose-response framework:

Figure 2: Dose-Response Continuum of Toxicological Measures

This continuum illustrates the progression from no effect through adverse effects to lethality. The Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) represents the highest dose that does not produce unacceptable toxicity in chronic studies [21], while the LD50 quantifies acute lethal potency [1]. Each parameter serves distinct purposes in hazard characterization and risk assessment.

Research Applications and Risk Assessment Framework

Derivation of Human Exposure Limits

NOAEL and LOAEL values serve as critical points of departure for establishing human exposure thresholds. The reference dose (RfD) represents a daily exposure level unlikely to produce adverse effects in humans over a lifetime and is calculated using the following standard formula [22] [20]:

RfD = NOAEL ÷ (UFinter × UFintra × UFsubchronic × UFLOAEL × MF)

Where uncertainty factors (UF) account for:

- UFinter (Interspecies variability): Typically 10-fold to account for differences between test species and humans [20]

- UFintra (Intraspecies variability): Typically 10-fold to protect sensitive human subpopulations [20]

- UFsubchronic (Study duration): 10-fold when extrapolating from subchronic to chronic exposure [20]

- UFLOAEL (LOAEL to NOAEL extrapolation): 10-fold when only LOAEL is available [20]

- MF (Modifying factor): 1-10 based on professional judgment of database completeness [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for NOAEL/LOAEL Studies

| Research Material | Specifications | Application in Toxicity Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Animals | Specific pathogen-free rodents (rats, mice); defined strains (Sprague-Dawley, Wistar, Beagle dogs) | In vivo toxicity assessment; species selection critical for human relevance [21] |

| Clinical Chemistry Analyzers | Automated systems for serum biochemistry (liver enzymes, renal markers, electrolytes) | Detection of organ-specific toxicity [23] |

| Histopathology Equipment | Tissue processors, microtomes, stains (H&E, special stains) | Morphological assessment of target organs [22] |

| Environmental Control Systems | Regulated housing conditions (temperature, humidity, light cycles) | Standardization to minimize confounding variables [22] |

| Statistical Software | Packages for dose-response modeling (PROC PROBIT, BMDS) | Statistical analysis of treatment effects [23] |

| Sanggenon A | Sanggenon A, CAS:76464-71-6, MF:C25H24O7, MW:436.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pirmagrel | Pirmagrel|CAS 85691-74-3|Thromboxane Synthase Inhibitor | Pirmagrel is a potent thromboxane synthase inhibitor for cardiovascular research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Methodological Approaches

Benchmark Dose (BMD) Modeling

While the NOAEL/LOAEL approach remains widely used, Benchmark Dose (BMD) modeling represents a more sophisticated statistical alternative that utilizes the entire dose-response curve rather than a single point [20]. The BMD is defined as the dose that produces a predetermined change in response rate compared to background (benchmark response, typically 5-10%) [1]. The lower confidence limit on the BMD (BMDL) is often used as a point of departure for risk assessment, offering advantages over NOAEL including better utilization of dose-response data, reduced dependence on dose spacing, and quantifiable uncertainty characterization [20].

Special Cases and Limitations

Non-Threshold Toxicants: For non-threshold carcinogens, theoretical considerations suggest that no completely safe exposure level exists [1] [22]. In such cases, NOAEL and LOAEL concepts are inappropriate, and alternative approaches such as T25 (chronic dose rate producing 25% tumor incidence) or BMD10 (dose producing 10% tumor incidence) are employed for risk assessment [1].

Study Design Limitations: NOAEL values are influenced by study design factors including dose selection, sample size, and measurement sensitivity [24]. Inconsistent definitions of adversity among toxicologists further complicate cross-study comparisons and regulatory standardization [24].

NOAEL and LOAEL values are integral to regulatory toxicology, serving as the basis for establishing Acceptable Daily Intakes (ADIs), Reference Doses (RfDs), and Occupational Exposure Limits (OELs) [1]. Regulatory frameworks such as the U.S. EPA's Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) and the Clean Water Act criteria development rely on rigorous evaluation of NOAEL/LOAEL data from standardized testing protocols [20].

In conclusion, NOAEL and LOAEL represent foundational concepts in threshold toxicology, providing practical benchmarks for chemical risk assessment. While methodological advancements such as BMD modeling offer enhanced statistical approaches, the NOAEL/LOAEL paradigm remains firmly established in both regulatory practice and drug development workflows. Understanding the theoretical basis, methodological requirements, and practical applications of these dose descriptors remains essential for toxicologists and risk assessors across research and regulatory domains.

The dose-response relationship forms the cornerstone of toxicological science, providing a fundamental framework for understanding the biological effects of chemical substances on living organisms. This principle, which can be traced back to ancient Greek concepts of moderation and harmony, posits that the magnitude of a biological response is a function of the concentration or dose of a chemical [25]. In modern toxicology, this relationship is quantitatively expressed through a suite of standardized metrics that enable scientists, researchers, and drug development professionals to evaluate both the hazardous effects and safe exposure levels of substances. Key among these metrics are LD50 (Lethal Dose 50%), LOAEL (Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level), NOAEL (No Observed Adverse Effect Level), and DNEL (Derived No-Effect Level), each serving a distinct purpose in hazard characterization and risk assessment [1].

The conceptual foundation of dose-response was evident in ancient times, with Hesiod's 'Harmonia' in the 8th century BC and the Delphic maxim 'meden agan' (nothing too much) expressing the core principle that substance effects are dose-dependent [25]. Mithridates VI Eupator (132-63 BCE) practically demonstrated this concept through his experiments with poisons and antidotes, developing tolerance through progressive sublethal dosing—an early exploration of the threshold concept now formalized in modern toxicology [25]. Paracelsus (1493-1541) later crystallized this understanding with his famous declaration that "the dose makes the poison," establishing the fundamental principle that all chemicals can be toxic at sufficient exposure levels [25].

In contemporary toxicology, the dose-response curve provides a visual representation of this relationship, enabling the derivation of critical toxicity measures that inform regulatory decisions, safety standards, and pharmaceutical development. This technical guide explores the interrelationship of these key parameters, their experimental determination, and their application in protecting human health and the environment.

Fundamental Concepts in Dose-Response Toxicology

Key Toxicity Measures and Their Definitions

Toxicological dose descriptors are standardized metrics that quantify the relationship between chemical exposure and biological effects. These parameters form the basis for hazard classification, risk assessment, and the derivation of safe exposure limits [1].

Table 1: Core Toxicological Dose Descriptors and Their Definitions

| Acronym | Full Name | Definition | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| LD50 | Lethal Dose 50% | A statistically derived dose at which 50% of test animals are expected to die [1] | Acute toxicity assessment and classification |

| LC50 | Lethal Concentration 50% | The concentration of a substance in air or water that causes death in 50% of test animals over a specified period [26] | Inhalation and aquatic toxicity evaluation |

| NOAEL | No Observed Adverse Effect Level | The highest exposure level at which no biologically significant adverse effects are observed [1] [27] | Chronic toxicity studies and derivation of safety thresholds |

| LOAEL | Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level | The lowest exposure level at which biologically significant adverse effects are observed [1] [27] | Risk assessment when NOAEL cannot be determined |

| DNEL | Derived No-Effect Level | The exposure level below which no adverse effects are expected for human populations [1] | Human health risk assessment and regulatory standard setting |

The Dose-Response Curve Framework

The dose-response curve graphically represents the relationship between the dose of a substance and the magnitude of the biological response. This curve typically follows a sigmoidal shape, with response increasing with dose. The critical parameters—LD50, NOAEL, LOAEL—occupy specific positions along this curve, illustrating their interrelationships [1] [27].

The visualization above illustrates the fundamental relationship between key toxicological parameters on a standard dose-response curve. The NOAEL represents the highest point on the curve before adverse effects become apparent, establishing the upper bound of apparent safety. The LOAEL marks the transition where adverse effects first become detectable, indicating the threshold of toxicity. Further along the curve, the LD50 represents the point of significant mortality, characterizing a substance's acute lethal potential [1] [27]. The DNEL is derived by applying assessment factors to the NOAEL (or LOAEL when NOAEL is unavailable) to establish a human safety threshold, accounting for interspecies and intra-human variability [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Acute Toxicity Testing (LD50/LC50 Determination)

The determination of LD50 and LC50 values follows standardized experimental protocols designed to quantify acute toxicity. These tests measure the lethal potential of substances through various exposure routes.

Table 2: LD50/LC50 Experimental Protocol Overview

| Protocol Aspect | Standard Specifications | Methodological Details |

|---|---|---|

| Test Organisms | Rodents (rats, mice), aquatic species (fish, Daphnia) | Healthy young adult animals, specific pathogen-free status [26] |

| Exposure Routes | Oral, dermal, inhalation | Route selection based on anticipated human exposure scenarios [1] [26] |

| Dose Concentrations | 5-6 geometrically spaced doses | Range-finding studies determine appropriate concentration series [26] |

| Observation Period | 14 days for mammals, 24-96 hours for aquatic species | Monitoring for mortality, clinical signs, and behavioral changes [26] |

| Statistical Analysis | Bliss probit method, Karber's method, Litchfield-Wilcoxon | Computerized statistical packages for precise LD50 calculation with confidence intervals [26] |

For inhalation studies, the LC50 is determined by exposing test animals to carefully controlled atmospheric concentrations of the test substance for a specified duration (typically 2-4 hours) [26]. In aquatic toxicity testing, the exposure time must be clearly specified (e.g., 24-hour LC50, 48-hour LC50, or 96-hour LC50) as toxicity increases with exposure duration [26]. The experimental data are analyzed using statistical methods such as probit analysis or graphical interpolation to determine the precise concentration or dose that would be lethal to 50% of the test population.

Repeated Dose Toxicity Testing (NOAEL/LOAEL Determination)

NOAEL and LOAEL values are derived from repeated dose toxicity studies that evaluate the effects of prolonged chemical exposure. These studies provide critical data for establishing safety thresholds and identifying target organs of toxicity.

Standard Study Designs:

- 28-day repeated dose study: Initial screening for general toxicity patterns

- 90-day subchronic study: Comprehensive evaluation of cumulative effects

- Chronic toxicity studies: Exposure for majority of test species' lifespan [1]

Methodological Framework:

- Dose Group Selection: Typically 3-5 dose groups plus control

- Dose Level Identification: Range from no-effect to clearly adverse effect levels

- Endpoint Monitoring: Clinical observations, clinical pathology, histopathology

- Statistical Analysis: Identification of highest dose with no adverse effects (NOAEL) and lowest dose with adverse effects (LOAEL) [1] [27]

The NOAEL is identified as the highest tested dose that does not produce statistically or biologically significant adverse effects compared to the control group. The LOAEL is the lowest tested dose at which such adverse effects are observed [27]. These values are critically important for deriving threshold safety exposure levels for humans, including the Derived No-Effect Level (DNEL), occupational exposure limits (OELs), and acceptable daily intake (ADI) values [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Toxicity Testing | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Rodents | In vivo model for mammalian toxicity | LD50 determination, repeated dose studies [26] |

| Daphnia magna | Freshwater crustacean for aquatic toxicity screening | LC50 testing, environmental hazard assessment [1] |

| Cell Culture Systems | In vitro models for mechanistic toxicology | Preliminary screening, mode of action studies |

| Analytical Standards | Reference materials for dose verification | Quantitative analysis, method validation |

| Pathology Reagents | Tissue processing and staining | Histopathological evaluation in NOAEL/LOAEL studies |

| Environmental Chambers | Controlled atmosphere for inhalation studies | LC50 determination via inhalation route [26] |

| Statistical Software | Dose-response modeling and curve fitting | LD50/LC50 calculation, benchmark dose modeling [26] |

| Tolindate | Tolindate, CAS:27877-51-6, MF:C18H19NOS, MW:297.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Columbamine | Columbamine, CAS:3621-36-1, MF:C20H20NO4+, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Data Comparison and Interpretation

Toxicity Value Ranges and Classification

Toxicological dose descriptors span orders of magnitude, reflecting the vast differences in potency among chemical substances. Understanding these ranges is essential for proper hazard assessment and classification.

Table 4: Comparative Ranges of Key Toxicological Parameters

| Toxicity Measure | Typical Units | Value Range Examples | Interpretation Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| LD50 (oral, rat) | mg/kg body weight | <5 (very toxic) to >5000 (practically non-toxic) | Lower value indicates higher toxicity [1] |

| LC50 (inhalation, rat) | mg/L or ppm | <0.1 (highly toxic) to >10 (low toxicity) | Concentration-dependent, exposure time must be specified [26] |

| NOAEL | mg/kg bw/day | Varies by substance and study duration | Higher value indicates lower chronic toxicity [1] |

| EC50 (ecotoxicity) | mg/L | <1 (very toxic) to >100 (low toxicity) | Environmental hazard classification [1] |

The interpretation of these values requires careful consideration of study design and test conditions. For example, the LD50 of a single substance can vary significantly based on the route of administration, as demonstrated by the insecticide dichlorvos, which shows oral, dermal, and inhalation LD50 values of 56 mg/kg, 75 mg/kg, and 1.7 ppm respectively in rats [26]. Similarly, LC50 values for aquatic organisms must be interpreted in context with exposure duration, as toxicity typically increases with longer exposure times.

DNEL Derivation and Application

The Derived No-Effect Level (DNEL) represents the human exposure threshold below which adverse effects are not expected. It is derived from animal study NOAELs (or LOAELs) through the application of assessment factors that account for various uncertainties:

DNEL Derivation Formula: DNEL = NOAEL / (UF₠× UF₂ × UF₃ × UF₄ × UF₅)

Where assessment factors (UF) typically include:

- Interspecies variability (UFâ‚): Typically 10-fold for animal-to-human extrapolation

- Intra-human variability (UFâ‚‚): Typically 10-fold for sensitive subpopulations

- Study duration (UF₃): Subchronic to chronic extrapolation

- LOAEL to NOAEL (UFâ‚„): When only LOAEL is available

- Database completeness (UFâ‚…): Quality and comprehensiveness of available data [1] [2]

This approach mirrors the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Reference Dose (RfD) methodology, which similarly divides the NOAEL by uncertainty factors to derive a human safety threshold [2]. The resulting DNEL serves as a benchmark for evaluating human exposure risks in occupational, consumer, and environmental contexts, forming the basis for regulatory standards and risk management decisions.

Advanced Concepts and Modern Approaches

Beyond Traditional Metrics: Benchmark Dose and Hormesis

While NOAEL and LOAEL have long served as the foundation for risk assessment, several limitations have prompted the development of complementary approaches:

Benchmark Dose (BMD) Modeling:

- Utilizes the entire dose-response curve rather than a single point

- BMDLâ‚â‚€ represents the lower confidence limit of the dose that produces a 10% response

- Provides more robust statistical basis than NOAEL/LOAEL approach [1]

T25 and BMD10 for Carcinogens: For non-threshold carcinogens where NOAEL cannot be identified, the T25 (chronic dose rate producing 25% tumor incidence) or BMD10 (dose producing 10% tumor incidence) may be used to calculate a Derived Minimal Effect Level (DMEL) [1].

Hormesis Concept: The historical practice of Mithridates, who developed tolerance to poisons through progressive sublethal dosing, illustrates the phenomenon of hormesis—the biphasic dose response characterized by low-dose stimulation and high-dose inhibition [25]. This concept, recognized since ancient times but now gaining renewed scientific attention, suggests that some substances may exhibit beneficial effects at very low doses despite being toxic at higher exposures.

Integration into Risk Assessment Framework

The dose descriptors discussed form a cohesive framework for modern chemical risk assessment:

This integrated framework demonstrates how experimentally derived dose descriptors feed into the risk assessment process, ultimately informing regulatory standards and protective measures. The DNEL and related metrics (Reference Dose, Predicted No-Effect Concentration) serve as the critical bridge between toxicological science and public health protection, enabling evidence-based decision-making in chemical regulation and pharmaceutical development.

The dose-response relationship, visually represented through the dose-response curve and quantified through parameters such as LD50, NOAEL, LOAEL, and DNEL, provides an essential conceptual framework for modern toxicology. These interconnected metrics enable researchers and regulatory professionals to characterize chemical hazards, derive safe exposure thresholds, and protect human health and environmental quality. While traditional approaches focusing on single-point estimates (NOAEL, LOAEL) remain widely used, advances in statistical modeling and benchmark dose methodology offer enhanced precision for risk assessment. The continued evolution of these concepts, building upon foundations laid centuries ago, ensures that toxicological science remains capable of addressing emerging chemical challenges through rigorous, quantitative assessment of dose-response relationships.

This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the fundamental units of measurement employed in toxicological studies, specifically focusing on mg/kg body weight (bw) for LD50 (Lethal Dose 50%) and mg/L for LC50 (Lethal Concentration 50%) and EC50 (Median Effective Concentration). Within the broader context of toxicity measure research, a precise understanding of these units and their application is paramount for accurate risk assessment, drug development, and regulatory decision-making. This whitepaper delineates the experimental protocols for deriving these descriptors, presents quantitative data in structured formats, and explores their integral role in establishing safety thresholds for human health and the environment, serving the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Toxicological dose descriptors are quantitative measures that identify the relationship between a specific effect of a chemical substance and the dose or concentration at which it occurs [1]. These descriptors, including LD50, LC50, and EC50, form the cornerstone of hazard identification and risk assessment. They are utilized for the GHS (Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals) hazard classification and are critical for deriving no-effect threshold levels for human health, such as the Derived No-Effect Level (DNEL) or Reference Dose (RfD), and for the environment, known as the Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC) [1]. The accurate interpretation of their units—milligrams per kilogram body weight (mg/kg bw) and milligrams per liter (mg/L)—is non-negotiable for valid cross-study comparisons and evidence-based safety determinations.

Core Concepts and Units of Measurement

LD50 and the Meaning of mg/kg bw

The LD50 (Lethal Dose 50%) is a statistically derived dose of a substance that causes death in 50% of a test animal population following a single exposure [1] [9]. It is a standard measure of acute toxicity.

The unit mg/kg bw represents the mass of the substance administered per unit of body weight of the test animal.

- mg: The mass of the chemical agent in milligrams.

- kg bw: The body weight of the test subject in kilograms.

This unit normalizes the administered dose to the animal's body size, allowing for a more equitable comparison of toxicity across animals of different weights and, cautiously, across different species [9]. For example, an LD50 (oral, rat) of 5 mg/kg means that 5 milligrams of the substance per 1 kilogram of the rat's body weight, administered in a single oral dose, is expected to be lethal to half of the test population [9]. A lower LD50 value indicates higher acute toxicity [1].

LC50 and EC50 and the Meaning of mg/L

The LC50 (Lethal Concentration 50%) is used primarily for inhalation toxicity, where exposure occurs through a medium like air or water. It is the concentration of a chemical in air that causes death in 50% of the test animals after a specified exposure duration, typically 4 hours [1] [9].