From Lab to Reality: A Comprehensive Guide to Laboratory-to-Field Extrapolation Methods

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed exploration of laboratory-to-field extrapolation methodologies.

From Lab to Reality: A Comprehensive Guide to Laboratory-to-Field Extrapolation Methods

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed exploration of laboratory-to-field extrapolation methodologies. It covers the foundational principles underscoring the necessity of extrapolation, a diverse range of established and emerging technical methods, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing predictions, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing insights from ecotoxicology, computational physics, and machine learning, this guide serves as a critical resource for improving the accuracy and reliability of translating controlled laboratory results to complex, real-world environments, ultimately enhancing the efficacy and safety of biomedical and environmental interventions.

The Why and When: Foundational Principles and Challenges of Lab-to-Field Extrapolation

Core Concept Definition

Extrapolation is the process of estimating values outside the range of known data points, while interpolation is the process of estimating values within the range of known data points [1] [2].

The prefixes of these terms provide the clearest distinction: "extra-" means "in addition to" or "outside of," whereas "inter-" means "in between" [1]. In research, this translates to extrapolation predicting values beyond your existing data boundaries, and interpolation filling in missing gaps within those boundaries.

Table: Fundamental Differences Between Interpolation and Extrapolation

| Feature | Interpolation | Extrapolation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Location | Within known data range | Outside known data range [1] [2] |

| Primary Use | Identifying missing past values | Forecasting future values [1] |

| Typical Reliability | Higher (constrained by existing data) | Lower (probabilistic, more uncertainty) [1] |

| Risk Level | Relatively low | Higher, potentially dangerous if assumptions fail [2] |

Applications in Drug Development and Research

In Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), extrapolation plays a crucial role in translating findings across different contexts. Dose extrapolation allows researchers to extend clinical pharmacology strategies to related disease indications, dosage forms, and clinical populations without additional clinical trials [3]. This is particularly valuable in areas like pediatric drug development and rare diseases, where recruiting sufficient patients for efficacy studies is challenging [3].

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M15 MIDD guidelines provide a framework for these extrapolation practices, helping align regulator and sponsor expectations while minimizing errors in accepting modeling and simulation results [3].

Table: Common Methodologies for Interpolation and Extrapolation

| Method Type | Interpolation Methods | Extrapolation Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Linear | Linear interpolation | Linear extrapolation [1] |

| Polynomial | Polynomial interpolation | Polynomial extrapolation [1] |

| Advanced | Spline interpolation (piecewise functions) | Conic extrapolation [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Experimental Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification in molecular biology experiments [4] |

| MgClâ‚‚ | Cofactor for DNA polymerase activity in PCR reactions [4] |

| dNTPs | Building blocks (nucleotides) for DNA synthesis [4] |

| Competent Cells | Bacterial cells prepared for DNA transformation in cloning workflows [4] |

| Agar Plates with Antibiotics | Selective growth media for transformed bacterial colonies [4] |

| O-Desmethyl Midostaurin | O-Desmethyl Midostaurin, CAS:740816-86-8, MF:C34H28N4O4, MW:556.6 g/mol |

| Zabofloxacin | Zabofloxacin|CAS 219680-11-2|For Research |

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental FAQs

FAQ: No PCR Product Detected

Q: My PCR reaction shows no product on the agarose gel. What should I investigate?

Systematic Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Identify the Problem: Confirm the PCR reaction failed while gel electrophoresis system works (verify using DNA ladder) [4]

- List Possible Explanations: Check each Master Mix component (Taq DNA Polymerase, MgClâ‚‚, Buffer, dNTPs, primers, DNA template), equipment, and procedure [4]

- Collect Data: Test equipment functionality, review positive controls, verify reagent storage conditions, compare procedures with manufacturer instructions [4]

- Eliminate Explanations: Based on collected data, systematically eliminate non-issues (e.g., if positive control worked, eliminate entire kit as cause) [4]

- Experimental Verification: Design targeted experiments for remaining explanations (e.g., test DNA template quality via gel electrophoresis and concentration measurement) [4]

- Identify Root Cause: Implement fix (e.g., use premade master mix to reduce future errors) [4]

FAQ: No Clones Growing on Agar Plate

Q: My transformation plates show no colonies. What could be wrong?

Troubleshooting Workflow:

- Step 1: Verify problem location by checking control plates [4]

- Step 2: List explanations: plasmid issues, antibiotic problems, or incorrect heat shock temperature [4]

- Step 3: Collect data: Check positive control plate (should have many colonies), verify correct antibiotic and concentration, confirm water bath at 42°C [4]

- Step 4: Eliminate explanations: Competent cells (if positive control good), antibiotic (if correct type/conc.), procedure (if temperature correct) [4]

- Step 5: Experiment: Test plasmid integrity via gel electrophoresis, measure concentration, verify ligation by sequencing [4]

- Step 6: Identify cause: Often low plasmid DNA concentration [4]

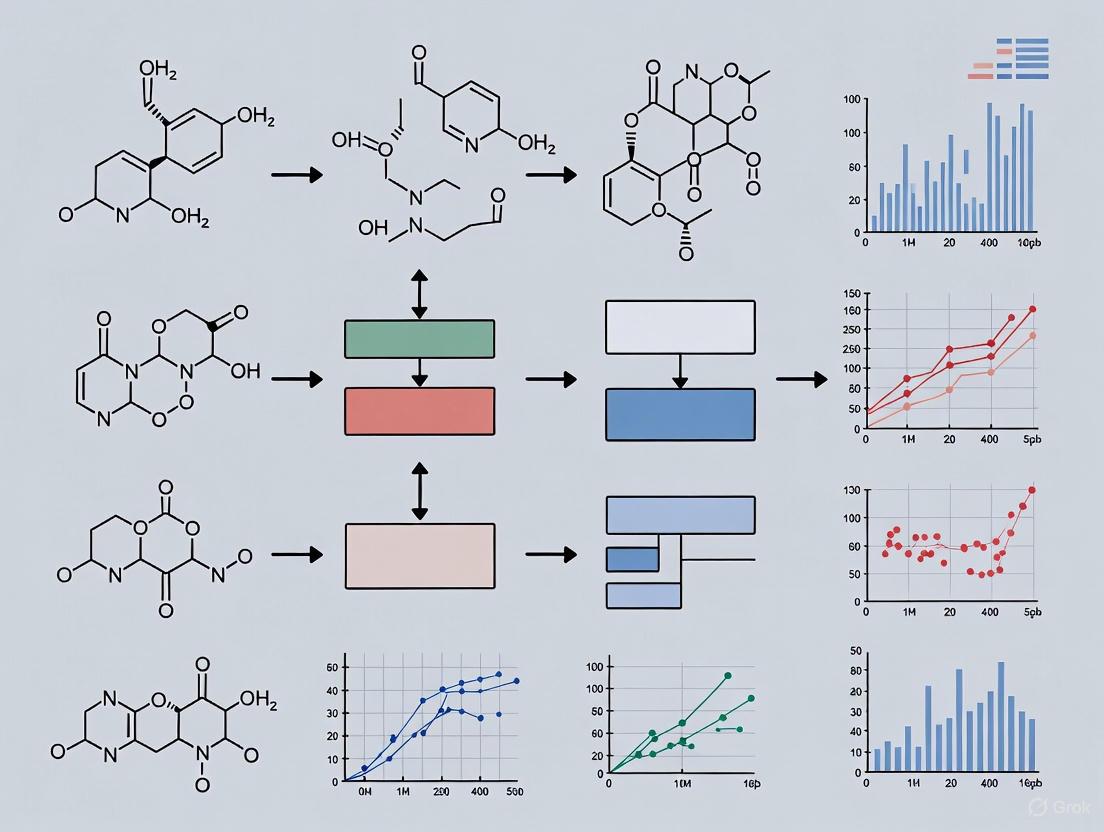

Visualization: Experimental Troubleshooting Workflow

Diagram Title: Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology

Critical Considerations for Extrapolation

Extrapolation carries inherent risks that researchers must acknowledge. The fundamental assumption that patterns within your known data range will continue outside that range can be dangerously misleading [2]. The potential for error increases as you move further from your original data boundaries [2].

Domain expertise is essential when deciding whether extrapolation is reasonable. For example, while advertising spend might predictably extrapolate to revenue increases, plant growth cannot be infinitely extrapolated due to biological limits [2]. Always document the limits of your extrapolations and the underlying assumptions in your research methodology.

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers and scientists working on laboratory to field extrapolation methods. Below, you will find structured answers to common challenges, supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visual workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why are my laboratory findings not replicating in real-world patient populations? This is often due to a "generalizability gap." The patient population in your controlled laboratory study (e.g., a clinical trial) often has a different distribution of key characteristics (like age, co-morbidities, or disease severity) compared to the real-world target population. If the treatment effect varies based on these characteristics, the average effect observed in the lab will not hold in the field [5]. Methodologies like re-weighting (standardization) can help extrapolate evidence from a trial to a broader target population [5].

2. What are the top operational bottlenecks causing laboratory data delays or failures? The most common operational bottlenecks in 2025 are related to billing, compliance, and workflow inefficiencies, which can disrupt research funding and operations. Key issues include rising claim denials, stringent modifier enforcement (e.g., Modifier 91 for repeat tests), and documentation gaps [6] [7]. The table below summarizes critical performance indicators and their impacts.

3. How can I check if my lab's operational health is causing setbacks? Audit your lab's Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) against healthy benchmarks for 2025. Being off-track in even one category can indicate systemic issues that threaten financial stability and, by extension, consistent research output [6].

| KPI | Healthy Benchmark (2025) | Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Clean Claim Rate | ≥ 95% | Increased re-submissions, payment delays [6] |

| Denial Rate | ≤ 5% | Direct revenue loss, often from medical necessity or frequency caps [6] |

| Days in Accounts Receivable (A/R) | ≤ 45 days | Cash flow disruption, hindering resource allocation [6] |

| First-Pass Acceptance Rate | ≥ 90% | High administrative burden to rework claims [6] |

| Specimen-to-Claim Latency | ≤ 7 days | Delays in revenue cycle and reporting [6] |

4. What specific regulatory pressures in 2025 could derail a lab's work? Regulatory pressure is intensifying, making compliance a frontline strategy for operational continuity [7]. Key areas of scrutiny include:

- Modifier Misuse: Automated denials for Modifier 91 (repeat tests) and Modifier 59 (unbundling) without strong ICD-10 justification [7].

- CLIA & NPI Mismatches: Claims denials for incorrect CLIA numbers or conflicting billing and performing provider details, especially for multi-site or reference labs [7].

- Prior Authorization: Surging denials for genomic, molecular, and high-cost pathology tests due to missing prior authorizations or justification [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing the Generalizability Gap in Research Populations

Problem: Efficacy observed in a tightly controlled randomized controlled trial (RCT) does not translate to effectiveness in the broader, heterogeneous patient population encountered in the field.

Solution: Implement evidence extrapolation methods, such as re-weighting (standardization), to generalize findings from the RCT population to a specified target population [5].

Experimental Protocol: Reweighting (Standardization) Method

- Objective: To estimate the average treatment effect in a target population using individual-level RCT data and the distribution of baseline characteristics from an observational data source [5].

- Materials:

- Individual-level data from the pivotal phase III trial.

- Observational healthcare database representing the target population (e.g., electronic health records).

- Methodology:

- Identify the Target Population: Apply the same inclusion/exclusion criteria used in the RCT to the observational data to identify patients who would have qualified for the trial [5].

- Estimate a Propensity Score (PS): Fit a logistic regression model predicting the probability of being a trial participant (vs. being in the observational dataset) conditional on baseline covariates (e.g., age, sex, disease severity) measured in both datasets [5].

- Calculate Weights: Assign each trial participant a weight equal to the PS odds:

PS / (1 - PS)[5]. - Estimate the Treatment Effect: Analyze the re-weighted trial data to estimate the average treatment effect in the target population. This provides an extrapolated measure of effectiveness [5].

Diagram 1: Reweighting evidence from RCT to target population.

Guide 2: Mitigating Operational and Billing Failures

Problem: High denial rates and slow revenue cycles disrupt lab funding and operational stability, directly impacting research continuity.

Solution: A proactive, 30-day operational review focused on compliance and process automation [7].

Experimental Protocol: 30-Day Lab Operational Health Check

- Objective: To identify and remediate key operational vulnerabilities in the lab's revenue cycle and compliance framework [7].

- Materials: Access to the last 12 months of claims data, denial reports (with CARC codes), payer contracts, and CLIA/NPI documentation for all testing sites [7].

- Methodology:

- Week 1: Analyze denial data. Pull denial reports from the last 12 months and categorize them by Claim Adjustment Reason Code (CARC), focusing on codes related to medical necessity (e.g., CARC 50) or frequency (e.g., CARC 151) [7].

- Week 2: Conduct a targeted documentation audit. For your top 20 CPT codes, audit for complete documentation (signed orders, test requisitions), prior authorization approval, and accurate mapping of performing CLIA numbers and NPIs [7].

- Week 3: Implement automation rules. Build or update automated rules in your billing system for modifier use (e.g., 91, 59) and CLIA loop configurations specific to each payer's requirements [7].

- Week 4: Reconcile payments and overpayments. Review Electronic Remittance Advice (ERA) and Explanation of Benefits (EOB) history to ensure proper reconciliation and that any identified overpayments are refunded within the required 60-day window to avoid compliance penalties [7].

Diagram 2: 30-day operational health check workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Individual-Level RCT Data | The foundational dataset containing participant-level outcomes and baseline characteristics for the intervention being studied [5]. |

| Observational Healthcare Database | A real-world data source (e.g., electronic health records, claims data) that reflects the characteristics and treatment patterns of the target population [5]. |

| Propensity Score Model | A statistical model (e.g., logistic regression) used to calculate the probability of trial participation, which generates weights to balance the RCT and target populations [5]. |

| AI-Powered Pre-Submission Checker | An operational tool that automates checks for coding errors, missing documentation, and payer-specific submission rules before a claim or report is finalized, reducing denials and errors [6] [8]. |

| Integrated LIS/EHR/Billing System | An operational platform that ensures seamless data sharing between lab, billing, and electronic health record systems, reducing manual entry errors and streamlining the workflow from test order to result [6]. |

| 2-chlorohexadecanoic Acid | 2-Chlorohexadecanoic Acid|CAS 19117-92-1|Inflammatory Lipid Mediator |

| Memnobotrin B | Memnobotrin B, MF:C27H37NO6, MW:471.6 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Q: The observed effect of my chemical mixture in vivo is much greater than predicted from individual component toxicity. What could be causing this?

A: This discrepancy often indicates synergistic interactions between mixture components or with other environmental stressors. Unlike simple additive effects, synergistic interactions can produce outcomes that are greater than the sum of individual effects [9]. Follow this systematic approach to isolate the cause:

- Confirm the exposure matrix: Verify that the actual exposure concentrations and bioavailability of each stressor match your experimental design. Bioavailability can be altered by environmental conditions like pH, organic matter, and temperature [10].

- Check for additional stressors: Evaluate uncontrolled variables such as temperature fluctuations, social stressors (e.g., population density in housing), or nutritional status of test organisms, as these can act as multiple stressors [9].

- Review the mechanism of action: Investigate if components have overlapping or interacting toxicodynamic pathways. For example, one component might inhibit the detoxification pathway of another [11].

Resolution Workflow:

Q: My laboratory toxicity results do not predict effects observed at contaminated field sites. Why is this happening?

A: This is a central challenge in laboratory-to-field extrapolation. Standardized laboratory tests often use a single chemical in an artificial medium (e.g., OECD artificial soil), which doesn't account for real-world complexity [10]. Key factors causing the discrepancy include:

- Differences in chemical bioavailability: Field soils have varying pH, organic matter, and clay content that strongly influence metal and organic chemical availability [10].

- Presence of multiple simultaneous stressors: Field populations experience combinations of chemicals, resource limitations, and climatic variations [11].

- Physiological and ecological context: Factors like nutritional status, age structure, and population density in the field differ from laboratory cultures [12].

Resolution Workflow:

Q: How can I design an environmentally relevant mixture study when real-world exposures involve hundreds of chemicals?

A: Testing all possible combinations is impractical. Instead, use a priority-based approach to design a toxicologically relevant mixture [9].

- Step 1: Utilize biomonitoring data: Base your mixture on chemicals detected in human cohorts or environmental samples (e.g., from NHANES or environmental monitoring programs) [9].

- Step 2: Apply toxicity screening: Use high-throughput in vitro bioassays (e.g., ToxCast/Tox21) to identify chemicals targeting relevant pathways [9].

- Step 3: Include known toxicants: Incorporate chemicals with established individual toxicity for your endpoint of interest [9].

- Step 4: Use realistic ratios: Mix components in proportions reflecting their environmental occurrence rather than using equimolar concentrations [9].

Experimental Protocols for Multiple Stressor Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Complex Contaminant Mixtures with In Vivo Models

This protocol is adapted from studies examining mixtures of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in pregnancy exposure models [9].

Objective: To evaluate the metabolic health effects of a defined chemical mixture during a critical physiological window (pregnancy).

Materials:

- Test System: Mouse model (e.g., C57BL/6J)

- Chemical Mixture: Atrazine, Bisphenol A (BPA), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)

- Dosing Solution Preparation:

- Prepare individual stock solutions for each chemical in appropriate vehicles (e.g., corn oil for lipophilic compounds, DMSO for others).

- Combine stocks to create a dosing mixture reflecting environmental exposure ratios.

- Administer via oral gavage to pregnant dams during specific gestation windows.

Procedure:

- Exposure Regimen: Expose experimental groups to the chemical mixture during pregnancy; include non-pregnant exposed dams and appropriate vehicle controls.

- Endpoint Assessment: Conduct glucose tolerance tests, measure body weight, visceral adiposity, and serum lipid profiles.

- Data Analysis: Compare outcomes between pregnant and non-pregnant exposed dams to assess pregnancy as an effect modifier.

Expected Outcomes: Metabolic health effects (e.g., glucose intolerance, increased weight, visceral adiposity, and serum lipids) are typically observed only in dams exposed during pregnancy, supporting the concept of complex stressors producing more significant effects during critical windows [9].

Protocol 2: Integrating Chemical and Non-Chemical Stressors

This protocol is adapted from studies combining flame retardant exposure with social stress in prairie voles [9].

Objective: To examine the interactive effects of a chemical mixture and a social stressor on behavior.

Materials:

- Test System: Prairie vole model

- Chemical Stressor: Firemaster 550 flame retardant mixture

- Non-Chemical Stressor: Paternal absence (early life social stress)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Use a 2x2 factorial design with four groups: (1) control, (2) flame retardant only, (3) paternal deprivation only, (4) combined exposure.

- Exposure: Administer flame retardant during early development; implement paternal deprivation during specified postnatal period.

- Behavioral Testing: In adult offspring, conduct tests for anxiety, sociability, and partner preference.

- Statistical Analysis: Use two-way ANOVA to test for main effects and interactions between chemical and social stressors.

Expected Outcomes: Flame retardant exposure may increase anxiety and alter partner preference, while paternal deprivation may cause increases in anxiety and decreases in sociability. The combination often produces unanticipated complex effects that differ from either stressor alone [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function/Application in Multiple Stressor Studies |

|---|---|

| Firemaster 550 | A commercial flame retardant mixture used to study real-world chemical exposure effects on neurodevelopment and behavior [9]. |

| Technical Alkylphenol Polyethoxylate Mixtures | Complex industrial mixtures with varying ethoxylate chain lengths used to investigate non-monotonic dose responses in metabolic health [9]. |

| Per-/Poly-fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | Environmentally persistent chemicals studied in binary mixtures to understand interactive effects on embryonic development [9]. |

| Phthalate Mixtures | Common plasticizers examined in defined combinations to assess cumulative effects on female reproduction and steroidogenesis [9]. |

| Bisphenol Mixtures (A, F, S) | Used in equimolar mixtures in in vitro models to investigate adipogenesis and cumulative effects of chemical substitutes [9]. |

| Metal Mixtures (Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn) | Studied in standardized earthworm tests (OECD artificial soil) to understand metal interactions and extrapolation to field conditions [10]. |

| Tobramycin Sulfate | Tobramycin Sulfate, CAS:49842-07-1, MF:C36H84N10O38S5, MW:1425.4 g/mol |

| Cladospolide B | Cladospolide B, CAS:96443-55-9, MF:C12H20O4, MW:228.28 g/mol |

Conceptual Framework for Multiple Stressor Analysis

The analysis of multiple stressors exists along a spectrum from purely empirical to highly mechanistic approaches, with varying trade-offs between precision and potential bias [11].

Methodological Decision Framework

Choosing the appropriate methodological approach depends on management needs, data availability, and the specific stressor combinations of interest [11].

| Analysis Approach | Best Use Case | Data Requirements | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Down [13] | Complex systems where starting with a broad overview is beneficial | Knowledge of system hierarchy and interactions | May miss specific component interactions |

| Bottom-Up [13] | Addressing specific, well-defined problems | Detailed understanding of individual components | May not capture higher-level emergent effects |

| Divide-and-Conquer [13] | Breaking down complex mixtures into manageable subproblems | Ability to divide system into meaningful subunits | Requires understanding of how to recombine solutions |

| Follow-the-Path [13] | Tracing exposure pathways or metabolic routes | Knowledge of stressor pathways through systems | May not capture all exposure routes |

| Case-Specific Management [11] | When management goals clearly define risk thresholds | Clear management objectives and acceptable risk levels | May not be generalizable to other contexts |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is toxicity often higher in field conditions compared to laboratory tests? Toxicity can increase in the field due to the presence of multiple additional stressors that are not present in a controlled lab environment. Laboratory tests typically assess the toxicity of a single chemical under optimal conditions for the test organisms. In contrast, field conditions expose organisms to a combination of chemical stressors (e.g., mixtures of pollutants) and non-chemical stressors (e.g., hydraulic stress, species interaction, resource limitation). This multiple-stress scenario can increase the sensitivity of organisms to toxicants. For example, a study found that exposure to the drug carbamazepine under multiple-stress conditions resulted in a 10- to more than 25-fold higher toxicity in key aquatic organisms compared to standardized laboratory tests [14].

FAQ 2: How can I account for mixture effects when extrapolating lab results to the field? The multi-substance Potentially Affected Fraction of species (msPAF) metric can be used to quantify the toxic pressure from chemical mixtures in the field. Calibration studies have shown a near 1:1 relationship between the msPAF (predicted risk from lab data) and the Potentially Disappeared Fraction of species (PDF) (observed species loss in the field). This implies that the lab-based mixture toxic pressure metric can be roughly interpreted in terms of species loss under field conditions. It is recommended to use chronic 10%-effect concentrations (EC10) from laboratory tests to define the mixture toxic pressure (msPAFEC10) for more field-relevant predictions [15].

FAQ 3: What are the key factors causing the laboratory-to-field extrapolation gap? Several factors can contribute to this gap, as identified in a case study with earthworms:

- Soil Properties: Factors like soil pH and organic matter content can significantly influence the availability and toxicity of metals in the field, which may not be fully replicated in standardized artificial soil tests [10].

- Multiple Stressors: Organisms in the field are simultaneously exposed to a suite of abiotic and biotic stressors (e.g., predation, competition, fluctuating temperatures, and water flow) which can increase their vulnerability to chemical stress [14].

- Chemical Mixtures: Organisms in natural environments are virtually always exposed to complex mixtures of chemicals, the effects of which are rarely tested in standard laboratory single-chemical toxicity assessments [15].

- Toxicokinetics: The uptake and distribution of chemicals can differ between laboratory media and natural soils or sediments [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Mitigating the Extrapolation Gap

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lab tests predict no significant risk, but adverse effects are observed in the field. | Presence of multiple chemical and/or non-chemical stressors in the field not accounted for in the lab. | Incorporate higher-tier, multiple-stress experiments (e.g., indoor stream mesocosms) that more closely simulate field conditions [14]. |

| Uncertainty in predicting the impact of chemical mixtures on field populations. | Reliance on single-chemical laboratory toxicity data. | Adopt mixture toxic pressure assessment models (e.g., msPAF) calibrated to field biodiversity loss data [15]. |

| Soil properties in the field alter chemical bioavailability, leading to unpredicted toxicity. | Standardized laboratory tests use a single, uniform soil type. | Conduct supplementary tests that account for key field soil properties (e.g., pH, organic carbon content) to better understand bioavailability [10]. |

Table 1: Documented Increases in Toxicity in Indoor Stream Multiple-Stress Experiments

This table summarizes the key findings from a mesocosm study that exposed aquatic organisms to carbamazepine and other stressors, demonstrating the significant increase in toxicity compared to standard lab tests [14].

| Organism | Stressors | Key Endpoint Measured | Lab-to-Field Toxicity Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chironomus riparius (non-biting midge) | Carbamazepine (80 & 400 μg/L), hydraulic stress, species interaction, low sediment organic content, terbutryn (6 μg/L) | Emergence | 10-fold or more |

| Potamopyrgus antipodarum (New Zealand mud snail) | Carbamazepine (80 & 400 μg/L), hydraulic stress, species interaction, low sediment organic content, terbutryn (6 μg/L) | Embryo production | More than 25-fold |

Table 2: Calibration of Predicted Mixture Toxic Pressure to Observed Biodiversity Loss

This table outlines the relationship between a lab-based prediction metric (msPAF) and observed species loss in the field, based on an analysis of 1286 sampling sites [15].

| Lab-Based Metric (msPAF) | Field Observation (PDF) | Interpretation for Risk Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| msPAF = 0.05 (Protective threshold based on NOEC data) | Observable species loss | The regulatory "safe concentration" (5% of species potentially affected) may not fully protect species assemblages in the field. |

| msPAF = 0.2 (Working point for impact assessment based on EC50 data) | ~20% species loss | A near 1:1 PAF-to-PDF relationship was derived, meaning 20% potentially affected species translates to roughly 20% species loss. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiple-Stress Indoor Stream Experiment

This methodology was used to investigate the toxicity of carbamazepine in a more environmentally relevant scenario [14].

- Objective: To assess the toxicity of the pharmaceutical carbamazepine (CBZ) to aquatic invertebrates under multiple-stress conditions.

- Test Organisms: Chironomus riparius (non-biting midge), Lumbriculus variegatus (blackworm), and Potamopyrgus antipodarum (New Zealand mud snail).

- Experimental Design:

- System: Six artificial indoor streams.

- Duration: 32 days.

- Exposure Concentrations: 80 μg CBZ/L and 400 μg CBZ/L.

- Multiple Stressors:

- Hydraulic stress.

- Species interaction.

- Sediment with low organic content.

- Co-exposure to a second chemical stressor (herbicide terbutryn at 6 μg/L).

- Key Endpoints:

- C. riparius: Emergence rate.

- P. antipodarum: Embryo production.

- L. variegatus: Various endpoints (study focused on the other two species for quantifying increased toxicity).

- Outcome Analysis: Compare results (e.g., LC50/EC50 values) with those from prior standardized single-stressor laboratory tests to calculate the fold-increase in toxicity.

Protocol 2: Earthworm Field Validation Study

This protocol is based on a case study extrapolating laboratory earthworm toxicity results to metal-polluted field sites [10].

- Objective: To relate data from the standardized OECD artificial soil earthworm toxicity test to effects on earthworms at polluted field sites.

- Test Organism: Earthworms (e.g., species like Eisenia fetida).

- Laboratory Phase:

- Perform the standard OECD artificial soil test for the chemicals of concern (e.g., cadmium, copper, lead, zinc).

- Determine toxicity endpoints (e.g., LC50, reproduction EC50).

- Field Validation Phase:

- Identify field sites with known gradients of pollution for the target chemicals.

- Sample earthworm populations at these sites to assess population density, biomass, and metal accumulation in tissues.

- Characterize key soil properties at each site (e.g., pH, organic matter content, cation exchange capacity) that influence metal bioavailability.

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the earthworm abundance and health in the field to the predictions made from the laboratory toxicity data.

- Analyze how field soil properties modify the expression of toxicity observed in the lab.

Visualizations of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Lab to Field Extrapolation Challenge

Diagram 2: msPAF to PDF Calibration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Laboratory-to-Field Extrapolation Studies

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Carbamazepine | A model pharmaceutical compound used to study the toxicity and environmental risk of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environments under multiple-stress conditions [14]. |

| Terbutryn | A herbicide used as a second chemical stressor in multiple-stress experiments to simulate the effect of pesticide mixtures on non-target aquatic organisms [14]. |

| Artificial Soil | A standardized medium (e.g., as per OECD guidelines) used in laboratory toxicity tests for soil organisms like earthworms, providing a uniform baseline for chemical testing [10]. |

| Test Organisms: Chironomus riparius, Lumbriculus variegatus, Potamopyrgus antipodarum, Earthworms (Eisenia spp.) | Key invertebrate species representing different functional groups and exposure pathways in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, used as bioindicators in standardized tests and field validation studies [14] [10]. |

| Mesocosm/Indoor Stream | An experimental system that bridges the gap between lab and field, allowing controlled manipulation of multiple stressors (chemical, hydraulic, biological) in a semi-natural environment [14]. |

| Parimycin | Parimycin |

| Asparenomycin B | Asparenomycin B, MF:C14H18N2O6S, MW:342.37 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I efficiently identify non-target species that might be affected by a pharmaceutical compound during ecological risk assessment?

Answer: You can use specialized databases that map drug targets across species. The ECOdrug database is designed specifically to connect drugs to their protein targets across divergent species by harmonizing ortholog predictions from multiple sources [16]. This allows you to reliably identify non-target species that possess the drug's target protein, helping to select ecologically relevant species for safety testing. For a broader search, the EPA's ECOTOX Knowledgebase is a comprehensive, publicly available resource providing information on adverse effects of single chemical stressors to ecologically relevant aquatic and terrestrial species, with data curated from over 53,000 references [17].

FAQ 2: What should I do if my drug candidate shows unexpected toxicity in non-target organisms during ecotoxicological screening?

Answer: First, investigate the potential role of transformation products (TPs). Research indicates that TPs (metabolites, degradation products, and enantiomers) can sometimes exhibit similar or even higher toxicity than the parent pharmaceutical compound [18]. For example, the R form of ibuprofen has shown significantly higher toxicity to algae and duckweed than other forms [18]. We recommend conducting a tiered testing plan that includes the major known TPs of your compound, leveraging ecotoxicology studies on species of different biological organization levels to build a robust, regulator-ready data set [19].

FAQ 3: Our drug discovery program has identified a potent small molecule, but it lacks sufficient oral bioavailability. What are the key steps to address this?

Answer: Addressing bioavailability challenges requires an integrated, cross-functional strategy. Initiate Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) work as early as possible, including formulation development and analytical method development [20]. Work with medicinal chemists to evaluate and improve the drug-like properties of the compound. Furthermore, we strongly encourage the use of experienced contract research organizations (CROs) that are highly efficient in obtaining pharmacokinetics and toxicology data crucial for the drug development industry [21] [20].

FAQ 4: Which specific ecotoxicological tests are considered essential for a preliminary environmental safety assessment of a new pharmaceutical?

Answer: An ecotoxicological test battery should include organisms of different biological organization levels. A standard screening battery includes luminescent bacteria (e.g., Vibrio fischeri), algae (e.g., Chlorella vulgaris), aquatic plants (e.g., duckweed, Lemna minor), crustaceans (e.g., Daphnia magna), and rotifers [18]. The data from these tests are used to develop chemical benchmarks and can inform ecological risk assessments for chemical registration [17]. The following table summarizes key ecotoxicity findings for common pharmaceuticals and their transformation products:

| Pharmaceutical (Parent Compound) | Transformation Product (TP) | Key Ecotoxicological Finding | Test Organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen (IBU) | R-Ibuprofen (enantiomer) | Significantly higher toxicity | Algae, Duckweed [18] |

| Naproxen (NAP) | R-Naproxen (enantiomer) | Higher toxicity observed | Luminescent Bacteria [18] |

| Tramadol (TRA) | O-Desmethyltramadol (O-DES-TRA) | Stronger inhibitor of opioid receptors; tendency for bioaccumulation | Fungi, Various Aquatic Organisms [18] |

| Sulfamethoxazole (SMZ) | N4-Acetylsulfamethoxazole (N4-SMZ) | Higher potential environmental risk; can transform back to parent compound | Various Aquatic Organisms [18] |

| Metoprolol (MET) | Metoprolol Acid (MET-ACID) | Slightly more toxic; more recalcitrant to biodegradation | Fungi [18] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconclusive or conflicting results when predicting cross-species drug target reactivity.

Solution: This is a common challenge due to ortholog prediction data being spread across multiple diverse sources [16].

- Step 1: Utilize the ECOdrug platform to harmonize ortholog predictions. Its interface is designed to integrate multiple prediction sources, providing a more reliable consensus [16].

- Step 2: Validate predictions with empirical data. Search the ECOTOX Knowledgebase for existing toxicity records for your chemical or structurally similar chemicals in the species of interest [17].

- Step 3: If empirical data is lacking, design a tiered-testing plan. Start with standardized acute toxicity tests on species predicted to be at high risk (those with conserved drug targets) before progressing to more chronic or sensitive endemic species [19].

Problem: High attrition rate of drug candidates due to toxicity failures in late-stage development.

Solution: Overcoming this requires a proactive, integrated strategy rather than a linear development process [20].

- Step 1: De-risking Strategy: Create an overall regulatory and clinical plan that includes CMC and toxicology experts from the very beginning. Use tools like the Drug Discovery Guide to map out necessary experiments and their status, focusing on "de-risking" the candidate early [21].

- Step 2: Early ADME/Tox Profiling: Conduct absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME/Tox) studies as early as possible. This includes investigating metabolic stability and the potential toxicity of major metabolites [21] [20].

- Step 3: Expert Engagement: Select an experienced board-certified toxicologist and thoroughly inspect the CROs performing IND-enabling animal studies to ensure quality and compliance with FDA guidelines [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ecotoxicity Screening Battery for Pharmaceuticals and their Transformation Products

1. Objective: To evaluate the potential toxic effects of a native pharmaceutical compound and its major transformation products on a range of aquatic organisms representing different trophic levels and biological organization [18].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Test Substances: Native pharmaceutical and its identified TPs (e.g., metabolites, degradation products).

- Test Organisms:

- Luminescent Bacterium: Vibrio fischeri (for acute toxicity, e.g., 30-min inhibition test) [18].

- Freshwater Algae: Chlorella vulgaris or similar (for 72-96 hour growth inhibition test) [18].

- Aquatic Plant: Duckweed, Lemna minor (for 7-day growth inhibition test) [18].

- Micro Crustacean: Daphnia magna (for 24-48 hour acute immobilization test) [18].

- Rotifers: (e.g., for acute and chronic toxicity tests) [18].

- Equipment: Standard laboratory equipment (incubators, light banks, pH meter, etc.), Microplate readers for absorbance/luminescence, Test vessels.

3. Methodology:

- Test Design: Prepare a geometric series of at least 5 concentrations of the test substance, plus a negative control (dilution water) and a positive control (e.g., reference toxicant).

- Exposure: Follow OECD or other standardized international guidelines for each test organism. Conditions (temperature, light, pH) must be kept constant and appropriate for each species.

- Replication: A minimum of three replicates per concentration is recommended.

- Endpoint Measurement: Measure the relevant inhibitory endpoint for each organism (e.g., luminescence inhibition for bacteria, growth rate for algae and duckweed, immobilization for Daphnia).

- Data Analysis: Calculate EC50 (Effective Concentration causing 50% effect) or similar values using appropriate statistical methods (e.g., probit analysis, non-linear regression).

Protocol 2: Integrated Workflow for Early-Stage Drug Candidate "De-risking"

1. Objective: To systematically advance a small molecule drug candidate by gathering critical data on its potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties to increase its commercial viability and reduce late-stage failure [21].

2. Methodology Overview: The process is managed using a flexible guide, often structured in a spreadsheet, where the status of each experiment is tracked (e.g., Completed/Green, Negative/Red, Ongoing/Blue) [21]. The key phases are:

- Final Product Profile: Define the target product profile first (e.g., route of administration, dosing regimen) as this dictates subsequent experiments [21].

- Target Validation & Assay Development: Compile information on the biological target and ensure robust, unambiguous assays are in place for screening [21].

- Hit-Phase: Identify compounds with sufficient potency (e.g., IC50/Ki < 10 µM) against the target from in vitro assays [21].

- Lead-Phase: Refine 1-2 novel classes of "Hit" compounds to improve potency and drug-like properties. This phase is critical for attracting commercial interest [21].

- Additional ADME/Tox: Conduct studies on absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity. This includes in silico predictions and experimental assays (e.g., metabolic stability in liver microsomes, plasma protein binding) often performed by specialized CROs [21].

The workflow for this integrated approach is visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| ECOdrug Database [16] | Database | Connects drugs to their protein targets across species to support ecological risk assessment and pharmacology. |

| EPA ECOTOX Knowledgebase [17] | Database | Provides curated data on chemical toxicity to aquatic and terrestrial species for risk assessment and chemical screening. |

| Drug Discovery Guide (MSIP) [21] | Framework/Template | An Excel-based guide outlining experiments to advance a small molecule drug candidate and "de-risk" development. |

| Luminescent Bacteria (Vibrio fischeri) [18] | Bioassay Organism | Rapid screening of acute chemical toxicity via inhibition of natural luminescence. |

| Duckweed (Lemna minor) [18] | Bioassay Organism | Assess phytotoxicity and chronic effects of chemicals on aquatic plant growth. |

| Micro Crustacean (Daphnia magna) [18] | Bioassay Organism | Standard acute immobilization test for evaluating chemical effects on a key freshwater zooplankton species. |

| Freshwater Algae (Chlorella vulgaris) [18] | Bioassay Organism | Assess chemical impact on primary producers via growth inhibition tests. |

| 9-Hydroxycanthin-6-one | 9-Hydroxycanthin-6-one, CAS:138544-91-9, MF:C14H8N2O2, MW:236.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Vanicoside B | Vanicoside B, MF:C49H48O20, MW:956.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The How: A Toolkit of Extrapolation Methods and Their Practical Applications

Core Concepts and Formulas

What are the fundamental principles of linear and polynomial extrapolation?

Linear extrapolation assumes a constant, linear relationship between variables, extending a straight line defined by existing data points to predict values outside the known range. It uses the formula for a straight line, ( y = mx + b ), where ( m ) is the slope and ( b ) is the y-intercept [22] [23].

Polynomial extrapolation fits a polynomial equation (e.g., ( y = a0 + a1x + a2x^2 + ... + anx^n )) to the data, allowing for the capture of curvilinear relationships and more complex trends that a straight line cannot represent [22] [24].

When should I choose one method over the other?

The choice depends entirely on the nature of your data and the underlying biological or physical process you are modeling.

- Use Linear Extrapolation when: The trend observed in your laboratory data is consistently linear, and you have no biological rationale to suggest this linear relationship will change within the prediction range. It is simple to implement and interpret [22].

- Use Polynomial Extrapolation when: Your laboratory data shows a clear curvilinear pattern (e.g., rapid initial growth that later stabilizes). It offers higher flexibility for modeling complex, non-linear relationships [22] [25].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and applicability of each method.

| Feature | Linear Extrapolation | Polynomial Extrapolation |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Assumption | Constant linear relationship [22] [23] | Relationship follows a polynomial function [22] |

| Best For | Short-term predictions; data with steady, linear trends [22] | Data with curvature or fluctuating trends [22] [25] |

| Key Advantage | Simple, intuitive, and computationally efficient [22] | Can fit a wider range of complex, non-linear data trends [22] |

| Key Risk | High inaccuracy if the true relationship is non-linear [22] | Overfitting, especially with high-degree polynomials [22] [24] |

| Common Laboratory Applications | Initial dose-response predictions; early financial forecasting; simple physical systems [22] | Population growth studies; modeling viral kinetics; cooling processes [22] |

| Kynapcin-28 | Kynapcin-28, MF:C19H12O10, MW:400.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Swinholide a | Swinholide a, MF:C78H132O20, MW:1389.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Common Extrapolation Issues

How do I prevent overfitting when using polynomial extrapolation?

Overfitting occurs when a model learns the noise in the training data instead of the underlying trend, leading to poor performance on new data.

- Use Cross-Validation: Validate your model using techniques like leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation. A high ( R^2 ) but low ( Q^2 ) (cross-validated ( R^2 )) is a classic sign of overfitting [25].

- Limit Polynomial Degree: Start with a lower degree polynomial (e.g., quadratic or cubic) and only increase if it provides a statistically significant improvement in model fit. Avoid unnecessarily high degrees [22].

- Apply Regularization: Techniques like Ridge or Lasso regression add a constraint on the polynomial coefficients, penalizing overly complex models and reducing overfitting [25].

- Ensure Sufficient Data: Have a sufficiently large dataset relative to the number of parameters in your model to provide a robust fit.

My extrapolations are highly inaccurate. What could be the cause?

Inaccurate extrapolations can stem from several sources, which you should systematically check.

- Violation of Linearity Assumption (for linear models): The most common cause is assuming a linear trend when the actual relationship is non-linear. Always plot your data to visually inspect the trend [22] [23].

- Ignoring Boundary Conditions: Physical and biological systems have natural limits. Extrapolating exponential growth indefinitely, for instance, will lead to implausible results. Incorporate known biological constraints into your models [22].

- Impact of Outliers: Outliers can disproportionately influence the fitted trend line, skewing predictions. Use robust regression techniques like Huber Regression, which is less sensitive to outliers, or carefully investigate anomalous data points [24].

- Data Mismatch: The data used for building the model may not fully represent the target population. For example, in paediatric drug development, simply extrapolating from adult data without accounting for developmental differences leads to error. Use methods like allometric scaling or physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to account for these differences [26] [27].

How can I quantify and communicate the uncertainty in my predictions?

Quantifying uncertainty is critical for responsible reporting of extrapolated results.

- Report Prediction Intervals: Instead of providing only a single predicted value, calculate and report a prediction interval (e.g., 95% prediction interval) which gives a range within which a future observation is expected to fall.

- Use Error Metrics: Calculate and present error-based validation metrics for your model. Common metrics include [25]:

- Perform Scenario Analysis: Present predictions based on a range of plausible models (e.g., linear, polynomial, exponential) to demonstrate to stakeholders how the conclusions depend on the chosen extrapolation method [29].

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Polynomial Regression Extrapolation for Laboratory Data

This protocol outlines the steps to develop and validate a polynomial extrapolation model using a standard statistical software environment like Python or R.

1. Data Preparation and Exploration

- Collect and clean your laboratory data (e.g., dose-concentration data, bacterial growth over time).

- Split the data into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) to build the model and a test set (20-30%) to validate it. Crucially, ensure the test set includes the extreme ends of your data range to best test extrapolation performance [25].

- Visually explore the data with a scatter plot to identify a potential curvilinear pattern.

2. Model Fitting and Degree Selection

- Fit polynomial models of increasing degree (1=linear, 2=quadratic, 3=cubic, etc.) to the training data.

- Use a model selection criterion like the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to compare models. The model with the lowest AIC/BIC is generally preferred, as it balances goodness-of-fit with model complexity.

- Avoid selecting a degree solely based on maximizing ( R^2 ), as this will always increase with complexity and lead to overfitting.

3. Model Validation

- Use the fitted model to predict values for the held-out test set.

- Calculate validation metrics (RMSE, MAE) on the test set, not the training set, to get an unbiased estimate of performance [25].

- Perform cross-validation on the training set (e.g., 5-fold or LOO) to further assess the model's stability.

4. Extrapolation and Reporting

- Use the validated model to generate predictions for the desired extrapolation range.

- Report the final model equation, the validation metrics, and the prediction intervals alongside the extrapolated values.

The workflow for this protocol is outlined below.

Protocol: Dose Extrapolation from Animal to Human using Allometric Scaling

A critical application in drug development is predicting human pharmacokinetic parameters, such as clearance (CL), from animal data.

1. Data Collection

- Obtain in vivo pharmacokinetic data (e.g., clearance) from preclinical species (commonly rat).

- Measure or obtain the unbound fraction in plasma (( f_u )) for the compound in the same species [26] [28].

2. Model Application

- Apply the Fraction-based Linear Extrapolation for Single Species Scaling (FLEX-SSS ( f_u ) Rat) method [26] [28].

- This method dynamically switches between two simple scaling formulas based on an optimized ( fu ) threshold:

- If ( fu ) is above the threshold, use the formula: ( CL{human} = CL{rat} \times (f{u,human} / f{u,rat}) ).

- If ( fu ) is below the threshold, use the simple scaling: ( CL{human} = CL_{rat} \times Scaling Factor ).

- The threshold and scaling factor are pre-optimized using a large training set of compounds.

3. Prediction and Consensus

- For increased accuracy, form a consensus prediction by combining the results of the FLEX method with a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest) built using molecular descriptors [26] [28].

- The consensus model has been shown to provide a balanced performance, significantly reducing the proportion of predictions with large errors [28].

The logical relationship of this advanced dose extrapolation method is shown in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details essential materials and computational resources for experiments involving extrapolation, particularly in a pharmacological context.

| Item / Reagent | Function / Relevance in Extrapolation |

|---|---|

| Preclinical PK Data | Provides the fundamental input data (e.g., Clearance, Volume of Distribution) from animal studies for allometric scaling and extrapolation to humans [26] [27]. |

| Human/Animal Plasma | Used to experimentally determine the unbound fraction (( f_u )), a critical parameter for correcting protein binding differences in pharmacokinetic extrapolation [26] [28]. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | The primary environment for implementing extrapolation models, from simple linear regression to complex machine learning algorithms and kernel-weighted methods [24] [25]. |

| PBPK Modeling Software | Mechanistic modeling tools that incorporate physiological parameters to simulate and extrapolate drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) across species [27]. |

| Kernel-Weighted LPR Script | An R-script implementing Kernel-weighted Local Polynomial Regression (KwLPR), a advanced non-parametric technique that can offer superior prediction quality over traditional regression [25]. |

| dichotomine C | Dichotomine C|β-Carboline Alkaloid|For Research |

| Panepophenanthrin | Panepophenanthrin|Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme Inhibitor |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the key difference between interpolation and extrapolation?

Interpolation is the estimation of values within the range of your existing data points. Extrapolation is the prediction of values outside the range of your known data, which carries significantly higher uncertainty and risk [22].

Why is linear extrapolation considered risky for long-term predictions?

Linear extrapolation assumes a trend continues indefinitely at a constant rate. Biological systems, however, often exhibit saturation, feedback loops, or other non-linear behaviors over time. This makes linear assumptions implausible for long-term forecasts, such as long-term survival or chronic drug effects [29] [22].

How is extrapolation formally used in drug development?

Regulatory agencies like the EMA and FDA accept the use of extrapolation in Paediatric Investigation Plans (PIPs). Efficacy data from adults can be extrapolated to children if the disease and drug effects are similar, significantly reducing the need for large paediatric clinical trials. This almost always requires supporting pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) data from the paediatric population [30] [27].

Are there alternatives to standard linear/polynomial extrapolation for complex data?

Yes, several advanced methods are available:

- Kernel-Weighted Local Polynomial Regression (KwLPR): A powerful non-parametric technique that can model local, non-linear trends without a global equation, often yielding better predictive quality [25].

- Machine Learning Models (e.g., Random Forest, Extra Trees): These can capture complex interactions and non-linearities. For example, Extra Trees regression introduces additional randomness to reduce overfitting and is effective with high-dimensional data [26] [24].

- Mixture Cure Models: Used in survival analysis to extrapolate long-term outcomes by separately modeling the proportion of "cured" patients and those who may still experience the event [29].

Smoothing and Function Fitting for Data Preprocessing

FAQs on Data Smoothing and Preprocessing

What is the primary purpose of data smoothing in a research context? Data smoothing refines your analysis by reducing random noise and outliers in datasets, making it easier to identify genuine trends and patterns without interference from minor fluctuations or measurement errors. This is particularly crucial for extrapolation research, as it helps reveal the underlying signal in noisy laboratory data, providing a more reliable foundation for predicting field outcomes [31] [32].

When should I avoid smoothing my data? You should avoid data smoothing in several key scenarios relevant to laboratory research:

- Anomaly Detection: When your research goal is to identify critical outliers, such as unexpected adverse reactions in toxicology studies or instrumental errors. Smoothing could mask these vital indicators [31].

- Real-time Monitoring: For systems tracking live data, like in-vivo physiological monitoring, smoothing may introduce dangerous delays or mask rapid, critical changes [31].

- Safety-Critical Systems: In contexts where every data fluctuation matters (e.g., measuring precise drug dosage levels), smoothing could obscure critical warnings [31].

- Legal and Regulatory Compliance: If your research requires full transparency of raw data for regulatory submission, smoothing may be inappropriate [31].

How do I choose the right smoothing technique for my time-series data from lab experiments? The choice depends on your data's characteristics and what you want to preserve. Below is a structured comparison of standard techniques.

| Technique | Best For | Key Principle | Considerations for Extrapolation Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moving Average [31] | Identifying long-term trends in data with little seasonal variation. | Calculates the average of a subset of data points within a moving window. | Simple to implement but can oversimplify and lag behind sudden shifts. |

| Exponential Smoothing [31] | Emphasizing recent observations, useful for short-term forecasting. | Applies decreasing weights to older data points, giving more importance to recent data. | Adapts quickly to recent changes but may overfit short-term noise. |

| Savitzky-Golay Filter [31] | Preserving the shape and peaks of data while smoothing. | Applies a polynomial function to a subset of data points. | Ideal for spectroscopic or signal data where retaining fine data structure is essential. |

| Kernel Smoothing [31] | Flexible smoothing without a fixed window size for visualizing data distributions. | Uses weighted averages of nearby data points. | Useful for data with natural variability, like ecological or population data. |

What are common pitfalls in data preprocessing that can affect model generalizability? A major pitfall is incorrect handling of data splits, leading to data leakage. If information from the test set (e.g., its global mean or standard deviation) is used to scale the training data, it creates an unrealistic advantage and results in models that fail to generalize to new, unseen field data [33]. Always perform scaling and normalization after splitting your data and fit the scaler only on the training set.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Performs Well on Lab Data but Fails on Field Data

Potential Cause: Overfitting to laboratory noise or failure to capture the true underlying trend. Your model may have learned the short-term fluctuations and anomalies specific to your controlled environment rather than the robust signal that translates to the field.

Solution: Apply data smoothing to denoise your training data and improve generalizability.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Moving Average Smoothing

- Acquire Dataset: Load your time-series laboratory data (e.g., drug response over time) [33].

- Select Window Size: Choose a window size (e.g., 5 periods). This is a critical parameter; a larger window creates a smoother curve but may obscure meaningful short-term patterns [31].

- Calculate the Average: For each data point, calculate the average of the 'n' preceding data points (including itself).

- Create Smoothed Series: Replace the original data points with the calculated moving averages to generate a new, smoothed data series.

- Validate: Test your model using the smoothed data for training and a hold-out validation set or new field data for evaluation to ensure performance has improved [34].

Issue: Poor Performance of a Distance-Based Algorithm (e.g., KNN)

Potential Cause: Features are on different scales, causing the algorithm to weigh higher-magnitude features more heavily. This is a common preprocessing error [33].

Solution: Apply feature scaling to normalize or standardize the data before model training.

Experimental Protocol: Feature Scaling for Algorithm Compatibility

- Split Data: Split your dataset into training and test sets. Crucially, all scaling parameters must be derived from the training set only. [33]

- Choose Scaling Method: Select an appropriate technique. Two common ones are:

- Normalization (Min-Max Scaling): Rescales features to a fixed range, typically [0, 1]. Use this for algorithms like k-NN or neural networks that require a bounded input [35]. Formula:

X_scaled = (X - X_min) / (X_max - X_min) - Standardization (Z-score): Transforms data to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This is less affected by outliers and is suitable for many algorithms [35]. Formula:

X_scaled = (X - mean) / std

- Normalization (Min-Max Scaling): Rescales features to a fixed range, typically [0, 1]. Use this for algorithms like k-NN or neural networks that require a bounded input [35]. Formula:

- Fit Scaler: Calculate the min/max or mean/standard deviation from the training data.

- Transform Data: Apply the transformation to both the training and test sets using the parameters learned from the training set.

- Proceed with Modeling: Train your model on the properly scaled training data.

Issue: Smoothing Process Removes Critical, Sharp Peaks from Signal Data

Potential Cause: The selected smoothing technique is too aggressive for the data characteristics. Simple methods like moving average can blur sharp, meaningful transitions [31].

Solution: Use a smoothing filter designed to preserve higher-order moments of the data, such as the Savitzky-Golay filter.

Experimental Protocol: Applying a Savitzky-Golay Filter

- Profile Your Data: Understand the width and shape of the features you need to preserve (e.g., peaks in chromatographic data).

- Set Parameters: Choose the window length and polynomial order. A shorter window preserves sharper features, while a higher polynomial order can fit more complex shapes.

- Implement the Filter: Apply the Savitzky-Golay algorithm, which works by fitting a low-degree polynomial to successive subsets of your data using linear least squares.

- Inspect Output: Visually and statistically compare the smoothed data to the original to ensure critical features are retained while noise is reduced.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Solutions for Data Preprocessing

| Item | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| IQR Outlier Detector | Identifies and removes extreme values that can skew analysis. | Calculates the Interquartile Range (IQR). Values below Q1 - 1.5IQR or above Q3 + 1.5IQR are typically considered outliers [35]. |

| Standard Scaler | Standardizes features by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance. | Essential for algorithms like SVM and neural networks. Prevents models from being biased by features with larger scales [33] [35]. |

| Exponential Smoother | Smooths time-series data with an emphasis on recent observations. | Uses a decay factor (alpha) to weight recent data more heavily, useful for adaptive forecasting [31] [32]. |

| Savitzky-Golay Filter | Smooths data while preserving crucial high-frequency components like peaks. | Ideal for spectroscopic, electrochemical, or any signal data where maintaining the shape of the signal is critical [31]. |

| Hongoquercin A | Hongoquercin A | Hongoquercin A is a sesquiterpenoid antibiotic for antimicrobial research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Cladosporide D | Cladosporide D | Cladosporide D is a 12-membered macrolide antibiotic for research, showing antifungal activity. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

Thermodynamic Extrapolation in Molecular Simulations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is thermodynamic extrapolation and what are its main advantages? Thermodynamic extrapolation is a computational strategy used to predict structural observables and free energies in molecular simulations at state points (e.g., temperatures, densities) different from those at which the simulation was performed. Its primary advantage is a significant reduction in computational cost when mapping phase transitions or structural changes, as it reduces the number of direct simulations required. [36]

Q2: Over what range is linear thermodynamic extrapolation typically accurate? The accuracy of linear extrapolation depends on the variable and the system:

- Density extrapolation is generally accurate only over a limited density range. [36]

- Temperature extrapolation can often be accurate across the entire liquid state for a given system. [36] For wider ranges, more sophisticated, non-linear methods like Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) are recommended. [37]

Q3: How does the Bayesian free-energy reconstruction method improve upon traditional extrapolation? This method reconstructs the Helmholtz free-energy surface ( F(V,T) ) from molecular dynamics (MD) data using Gaussian Process Regression. It offers key improvements: [37]

- It seamlessly handles irregularly spaced sampling points in the volume-temperature ( (V,T) ) space.

- It naturally propagates statistical uncertainties from the MD sampling into the final predicted thermodynamic properties.

- It can be combined with an active learning strategy to automatically select new, optimal ( (V,T) ) points for simulation, making the workflow fully automated and efficient.

Q4: Can thermodynamic extrapolation be applied to systems beyond simple liquids? Yes. Modern workflows are designed to be general and can be applied to both crystalline solids and liquid phases. For crystalline systems, the workflow can be augmented with a zero-point energy correction from harmonic or quasi-harmonic theory to account for quantum effects at low temperatures. [37]

Q5: What are common mistakes when setting up simulations for subsequent extrapolation? Common pitfalls include: [38]

- Mismatched Parameters: Failing to ensure that temperature and pressure coupling parameters in the production simulation match those used during the equilibration steps (NVT, NPT).

- Incorrect Input Paths: Manually entering paths for input files from previous simulation steps, which can lead to errors. Using an "Auto-fill" feature if available is recommended.

- Overlooking Advanced Settings: Not reviewing advanced parameters (e.g., for constraints) which might be hidden in a separate menu. Always cross-check these against your intended simulation design.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Extrapolation Accuracy Over Wide Parameter Ranges

- Problem: Predictions from linear extrapolation become inaccurate when trying to cover a large range of temperatures or densities.

- Solutions:

- Switch to a Non-linear Method: Implement a Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) framework to reconstruct the free-energy surface, which is better suited for capturing anharmonic effects and complex relationships over broad ranges. [37]

- Use a Recursive Interpolation Strategy: For a predefined range of conditions, a recursive interpolation scheme can be used to efficiently and accurately map out structural properties. [36]

- Increase Sampling Density: If using linear methods, reduce the extrapolation distance by adding more simulation data points within the range of interest. [36]

Issue 2: Incorporating Quantum Effects for Low-Temperature Predictions

- Problem: Classical MD simulations neglect quantum nuclear effects, leading to inaccurate thermodynamic properties (e.g., heat capacity) at low temperatures.

- Solutions:

- Apply a Zero-Point Energy Correction: Augment the free energy obtained from MD simulations with a zero-point energy correction derived from harmonic or quasi-harmonic calculations on the crystalline system. [37]

- Use a Hybrid Workflow: Adopt a unified workflow that combines the anharmonic free-energy surface ( F(V,T) ) from MD (using GPR) with a ZPE correction from HA/QHA. This leverages the strengths of both approaches. [37]

Issue 3: Managing Errors and Quantifying Uncertainty

- Problem: It is difficult to assess the reliability of extrapolated properties, as all MD data contains inherent statistical uncertainty.

- Solutions:

- Use a Bayesian Framework: Employ a method like Gaussian Process Regression, which inherently quantifies uncertainty. The GPR framework propagates statistical uncertainties from the input MD data through to the final predicted properties, providing confidence intervals (e.g., ± values) for quantities like heat capacity or thermal expansion. [37]

- Validate with Known Points: If possible, hold back a few simulated state points from the training set and use them to test the accuracy of the extrapolation predictions.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Comparison of Free-Energy Calculation Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Applicable Phases | Handles Anharmonicity? | Accounts for Quantum Effects? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic/Quasi-Harmonic Approximation (HA/QHA) [37] | Phonon calculations based on equilibrium lattice dynamics. | Crystalline solids only. | No. | Yes (via zero-point energy). |

| Classical MD with Thermodynamic Integration [37] | Free-energy difference along a path connecting two states. | Solids, liquids, and amorphous phases. | Yes. | No (classical nuclei). |

| Bayesian Free-Energy Reconstruction [37] | Reconstructs ( F(V,T) ) from MD data using Gaussian Process Regression. | Solids, liquids, and amorphous phases. | Yes. | When augmented with ZPE correction. |

Table 2: Key Properties Accessible via Free-Energy Derivatives

| Thermodynamic Property | Definition | Derivative Relation |

|---|---|---|

| Isobaric Heat Capacity (( C_P )) | Heat capacity at constant pressure. | Derived from second derivatives of ( G ) or ( F ). [37] |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient (( \alpha )) | Measures volume change with temperature at constant pressure. | ( \alpha = \frac{1}{V} \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)_P ) [39] |

| Isothermal Compressibility (( \beta_T )) | Measures volume change with pressure at constant temperature. | ( \betaT = -\frac{1}{V} \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial P} \right)T ) [39] |

| Speed of Sound (( c )) | Related to adiabatic compressibility. | Derived from ( F(V,T) ) surface. [39] |

Protocol 1: Bayesian Free-Energy Reconstruction Workflow

This protocol outlines the methodology for automated prediction of thermodynamic properties. [37]

- System Preparation: Construct the simulation cell for your system (crystal or liquid).

- Initial MD Sampling: Perform a set of NVT-MD simulations at selected ( (V, T) ) state points. These can be chosen irregularly.

- Data Collection: From each trajectory, extract the ensemble-averaged potential energy ( \langle E \rangle ) and pressure ( \langle P \rangle ).

- Free-Energy Surface Reconstruction: Use Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to reconstruct the Helmholtz free-energy surface ( F(V,T) ) from the collected data. The derivatives of ( F ) are constrained by the data: ( \partial F/\partial V = \langle P \rangle ) and ( \partial (F/T)/\partial T = - \langle E \rangle / T^2 ). [37]

- Uncertainty Propagation: The GPR framework automatically propagates the statistical uncertainties from the MD inputs to the reconstructed ( F(V,T) ) surface.

- Property Calculation: Calculate target thermodynamic properties by taking the appropriate analytical derivatives of the reconstructed ( F(V,T) ) surface.

- Active Learning (Optional): Use the GPR model's uncertainty estimation to identify new ( (V,T) ) points where additional MD sampling would most effectively reduce prediction error. Run new simulations at these points and iteratively update the model.

Protocol 2: NPT-Based Workflow for Specific Properties

A simplified, computationally efficient protocol for obtaining a subset of properties. [37]

- Equilibration: Perform NPT simulation at the target pressure (e.g., ( P = 1 ) bar) to equilibrate the system's density.

- Production Runs: Conduct a series of NPT-MD simulations, varying only the temperature across the range of interest.

- Data Analysis: Calculate properties like constant-pressure heat capacity ( C_P ) and density directly from the fluctuations and averages during the NPT simulation.

- Melting Point Estimation: For solids, the melting point can be identified by a discontinuity in properties like enthalpy or volume as a function of temperature.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ms2 [39] | A molecular simulation tool used to calculate thermodynamic properties (e.g., vapor-liquid equilibria, heat capacities) and transport properties via Monte Carlo or Molecular Dynamics in various statistical ensembles. |

| GROMACS [40] | A versatile software package for performing molecular dynamics simulations, primarily used for simulating biomolecules but also applicable to non-biological systems. |

| Lustig Formalism [39] | A methodological approach implemented in ms2 that allows on-the-fly sampling of any time-independent thermodynamic property during a Monte Carlo simulation. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [37] | A Bayesian non-parametric regression technique used to reconstruct free-energy surfaces from MD data while quantifying uncertainty. |

| Green-Kubo Formalism [39] | A method based on linear response theory, used within MD simulations to calculate transport properties (e.g., viscosity, thermal conductivity) from time-correlation functions of the corresponding fluxes. |

| Lepadin E | Lepadin E, MF:C26H47NO3, MW:421.7 g/mol |

| Aureoquinone | Aureoquinone|High-Purity Research Compound |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Physics-Based vs. Kinematics-Based Extrapolation Models

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: My extrapolation model shows good agreement in laboratory settings but fails when applied to field data. What could be the cause?

This is a common challenge in extrapolation methodology. The discrepancy often stems from the model's inability to account for all relevant physical processes or environmental variables present in field conditions. Physics-based models incorporate fundamental principles and may generalize better, but require accurate parameterization. Kinematics-based models, while computationally efficient, rely heavily on empirical relationships that may not hold outside laboratory conditions. Verify that your model includes all dominant physical mechanisms and validate it against multiple data sets from different environments. Incorporating adaptive learning cycles that iteratively refine predictions using new field data can significantly improve performance [41] [42].

FAQ: How do I decide between a physics-based and kinematics-based approach for my specific extrapolation problem?

The choice depends on your specific requirements for accuracy, computational resources, and need for physical insight. Use physics-based models when you need to understand underlying mechanisms, predict thermal properties, or work outside empirically validated regimes. These models solve conservative equations of hydrodynamics and can provide more reliable extrapolation. Kinematics-based approaches like the Heliospheric Upwind eXtrapolation (HUX) model are preferable when computational efficiency is critical and you're working within well-characterized empirical boundaries. For highest accuracy, consider hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both methodologies [41] [43].

FAQ: What are the most common sources of error in magnetic field extrapolation for coronal modeling?

The primary sources of error include: (1) Inaccurate specification of inner boundary conditions at the photosphere using input magnetograms; (2) Oversimplification of the current-free assumption in the Potential Field Source Surface (PFSS) model; (3) Incorrect placement of the source surface, typically set at 2.5 solar radii; and (4) Failure to properly account for heliospheric currents in the Schatten Current Sheet (SCS) model extension beyond the source surface. To minimize these errors, use high-quality synoptic maps from the Global Oscillations Network Group (GONG), validate against multiple observational data sets, and consider employing magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations for more physically accurate solutions [41].

FAQ: How can I improve the predictive accuracy of my solar wind forecasting model?

Implement these strategies: (1) Combine PFSS and SCS models for coronal magnetic field extrapolation up to 5 solar radii; (2) Apply empirical velocity relations (Wang-Sheeley-Arge model) based on field line properties at the outer coronal boundary; (3) Use validation metrics including correlation coefficients (target: >0.7) and root mean square error (target: <90 km/s for velocity); (4) Incorporate both kinematic and physics-based heliospheric extrapolation; (5) Compare predictions against hourly OMNI solar wind data for validation. The best implementations achieve correlation coefficients of 0.73-0.81 for solar wind velocity predictions [41] [43].