Ecological Risk Assessment for Biodiversity Protection: Integrating Methodologies for Conservation and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for applying Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) to biodiversity protection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Ecological Risk Assessment for Biodiversity Protection: Integrating Methodologies for Conservation and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for applying Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) to biodiversity protection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles bridging risk assessment and conservation goals, details methodological approaches including EPA tools and species sensitivity distributions, and addresses key challenges like incorporating rare species and scaling issues. By comparing ERA with other frameworks like Nature Conservation Assessment and the ecosystem services approach, it offers a validated, comparative perspective to inform robust environmental impact analyses and support sustainable development in biomedical research.

Bridging the Gap: Foundations of Ecological Risk Assessment and Biodiversity Conservation

Ecological risk assessment (ERA) is a critical scientific process that systematically evaluates the likelihood and magnitude of adverse effects occurring in ecological systems due to exposure to environmental stressors. In the context of biodiversity protection, ERA provides a structured methodology for understanding how human activities and environmental contaminants may impact ecosystems, species, and genetic diversity. The fundamental goal of probabilistic ecological risk assessment is to estimate both the likelihood and the extent of adverse effects on ecological systems from exposure to substances, based on comparing exposure concentration distributions with species sensitivity distributions derived from chronic toxicity data [1]. This scientific approach enables conservation researchers and policymakers to prioritize actions, allocate resources efficiently, and implement evidence-based protection measures for endangered species and vulnerable habitats.

The relationship between business operations and biodiversity further underscores the importance of robust ERA methodologies. Economic value generation is highly dependent on biodiversity, with approximately 50% of global GDP relying on ecosystem services. However, wildlife populations have experienced a 69% decline since 1970, and nearly one million species face extinction due to human activity [2]. This divergence highlights the urgent need for precise ecological risk assessment frameworks that can inform both conservation strategy and sustainable development practices.

Probabilistic Frameworks in Ecological Risk Assessment

Core Principles and Methodology

Probabilistic ecological risk assessment represents a significant advancement over deterministic approaches by explicitly addressing variability and uncertainty in risk estimates. The PERA framework is based on the comparison of an exposure concentration distribution (ECD) with a species sensitivity distribution (SSD) derived from chronic toxicity data [1]. This probabilistic approach results in a more realistic environmental risk assessment and consequently improves decision support for managing the impacts of individual chemicals and other environmental stressors.

The PERA framework integrates several key components: exposure assessment, which estimates the amount of chemical or stressor an organism encounters; hazard identification, which characterizes the inherent toxicity of the stressor; and risk characterization, which combines exposure and toxicity information to quantify the probability of adverse ecological effects [3]. This comprehensive methodology enables researchers to move beyond simple point estimates toward a more nuanced understanding of risk probabilities across different species, ecosystems, and temporal scales.

Advanced Probabilistic Framework for Contaminants of Emerging Concern

Recent research has developed sophisticated probabilistic frameworks specifically designed for assessing ecological risks of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs). These frameworks integrate the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) methodology and address multiple uncertainty types. The framework systematically incorporates different techniques to estimate uncertainty, evaluate toxicity, and characterize risk according to standard ERA methodology [4].

Table 1: Uncertainty Types in Probabilistic Ecological Risk Assessment

| Uncertainty Type | Description | Examples in ERA |

|---|---|---|

| Aleatory Uncertainty | inherent variability or heterogeneity of a system | seasonal variations in water quality, varying toxicities among species |

| Epistemic Uncertainty | stems from lack of knowledge, incomplete information | model structure uncertainty, parameter estimation uncertainty, scenario uncertainty |

| Model Uncertainty | uncertainty about how well the model represents the real system | differences in methods used to estimate toxicities |

| Parameter Uncertainty | uncertainties in the estimate of a model's input parameters | measurement errors, sampling variability |

| Scenario Uncertainty | stems from missing or incomplete information defining exposure | incomplete understanding of exposure pathways |

This framework employs a two-dimensional Monte Carlo Simulation (2-D MCS) to individually quantify variability (aleatory) and parameter uncertainties (epistemic) [4]. The probabilistic approach was successfully applied to a Canadian lake system for seven CECs: salicylic acid, acetaminophen, caffeine, carbamazepine, ibuprofen, drospirenone, and sulfamethoxazole. The study collected and analyzed 264 water samples from 15 sites between May 2016 and September 2017, concurrently sampling phytoplankton, zooplankton, and fish communities to assess ecological impacts [3].

The risk assessment results demonstrated considerable variation in ecological risk estimates. Based on the conservative estimate, the central tendency estimate of the ecological risk of mixture compounds was medium (Risk Quotient, RQ = 0.6) including drospirenone. However, the reasonably maximum estimate of the risk was high (RQ = 1.4) for mixture compounds including drospirenone. The high risk was primarily attributable to drospirenone, as its individual risk was high (RQ = 1.1) to fish [3]. This application illustrates how probabilistic frameworks can identify specific contaminants of concern and spatiotemporal patterns of high exposure for implementing targeted control measures.

Integrating Adverse Outcome Pathways into Risk Assessment

AOP Framework Fundamentals

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework represents a paradigm shift in ecological risk assessment by providing a mechanism-based organizing framework that links molecular-level perturbations to adverse outcomes at individual and population levels. The AOP framework describes sequential pathways that begin with molecular initiating events (MIEs) and proceed through a series of causal key events (KEs) to an adverse outcome (AO) [4]. These key events can be measured and used to confirm the activation of an AOP, making them powerful tools for risk assessment.

When sufficient quantitative information is available to describe dose-response and/or response-response relationships among MIEs, KEs, and AOs, a quantitative AOP (qAOP) can be developed to identify the point of departure that causes an adverse outcome in a dose-response assessment [4]. Examples include multi-stage dose-response models and dose-time-response models for aquatic species using qAOP. The AOP Wiki (http://aopwiki.org) serves as an open-source interface that facilitates collaborative AOP development, analogous to computational approaches used in the Human Toxome Project which successfully mapped molecular pathways of toxicity for endocrine disruptors [4].

AOP Workflow and Implementation

The integration of AOP into ecological risk assessment follows a structured workflow that connects molecular initiating events to ecosystem-level consequences. This approach enables researchers to move beyond traditional toxicity testing toward a more mechanistic understanding of how contaminants impact biological systems across multiple levels of organization.

Biodiversity-Specific Risk Assessment Tools and Metrics

The WWF Biodiversity Risk Filter

The WWF Biodiversity Risk Filter is a comprehensive online tool that enables companies and financial institutions to assess and act on biodiversity-related risks across their operations, value chains, and investments. This tool provides a structured approach to biodiversity risk assessment through four interconnected modules: Inform, Explore, Assess, and Act [2]. The tool combines state-of-the-art biodiversity data with sector-level information to help organizations understand biodiversity context across their value chain and prioritize actions where they matter most.

The Biodiversity Risk Filter assesses two primary types of biodiversity-related business risk: physical risk and reputational risk, with plans to incorporate regulatory risks in the future. Physical risk occurs when company operations and value chains are located in areas experiencing ecosystem service decline and are heavily dependent upon these services. Reputational risk emerges when stakeholders perceive that a company conducts business unsustainably with respect to biodiversity [2]. The tool assesses the state of biodiversity health using 33 different indicators that capture ecosystem diversity and intactness, species diversity and abundance, and ecosystem service provision.

Biodiversity Risk Metrics and Indicators

Effective biodiversity risk assessment requires robust metrics and indicators that capture the complex relationships between business activities and ecosystem health. The WWF Biodiversity Risk Filter evaluates dependencies and impacts on biodiversity through sector-specific weightings, recognizing that different industries have distinct relationships with natural systems.

Table 2: Biodiversity Risk Categories and Assessment Criteria

| Risk Category | Definition | Assessment Indicators | Business Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Risk | Operations face risk when located in areas with declining ecosystem services and highly dependent on them | Ecosystem service decline, dependency weighting, location-specific pressures | Operational cost increases, disruption of resource availability, production losses |

| Regulatory Risk | Potential for restrictions, fines, or compliance costs due to changing regulatory environments | Regulatory framework stability, implementation effectiveness, compliance requirements | Fines, operational restrictions, increased compliance costs, stranded assets |

| Reputational Risk | Stakeholder perception that business is conducted unsustainably regarding biodiversity | Media scrutiny, community relations, proximity to protected areas, operational performance | Loss of brand value, consumer boycotts, difficulties attracting talent |

The global significance of biodiversity risk is substantial, with recent data indicating that 35% of companies (approximately 23,000) and 64% of projects (approximately 15,000) have been linked to biodiversity risk incidents in a two-year period [5]. Geographic analysis reveals that Indonesia and Mexico have the highest proportional levels of biodiversity risk incidents, while Brazil experiences the most severe risk incidents [5].

Methodological Protocols for Ecological Risk Assessment

Standardized Assessment Workflow

The ecological risk assessment process follows a structured methodology comprising three major steps: exposure assessment, toxicity assessment, and risk characterization [4]. The exposure assessment estimates the concentration of a stressor that ecological receptors encounter, while toxicity assessment predicts the health impacts per unit of exposure. Risk characterization integrates these analyses to predict ecological risk to exposed organisms.

For complex mixture assessment, two primary models are employed: the "whole mixture approach" and "component-based analysis." The whole mixture approach studies chemical combinations as a single entity without evaluating individual components, suitable for unresolved mixtures. The component-based approach considers mixture effects through individual component responses, typically using the concentration addition (CA) method which sums "toxic units" from each chemical [4]. The CA method assumes each chemical contributes to overall toxicity, meaning the sum of many components at or below effect thresholds can still produce significant combined toxicity.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Comprehensive ecological risk assessment requires specialized reagents, analytical tools, and methodological approaches to generate reliable data for decision-making.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools for Ecological Risk Assessment

| Research Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Species Sensitivity Distribution (SSD) Models | Derivation of protective concentration thresholds based on multi-species toxicity data | Chronic toxicity data from at least 8-10 species across taxonomic groups; log-normal or log-logistic distribution fitting |

| Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Wiki | Collaborative knowledge base for developing and sharing AOP frameworks | Structured ontology with molecular initiating events, key events, and adverse outcomes; quantitative AOP development for dose-response modeling |

| Chemical Analytical Standards | Quantification of contaminant concentrations in environmental matrices | Certified reference materials for target analytes (e.g., pharmaceuticals, pesticides); isotope-labeled internal standards for mass spectrometry |

| Toxicity Testing Assays | Assessment of adverse effects at multiple biological organization levels | In vitro bioassays for high-throughput screening; in vivo tests with standard test species; molecular biomarkers for early warning |

| Two-Dimensional Monte Carlo Simulation | Separate quantification of variability and uncertainty in risk estimates | Iterative sampling from exposure and effects distributions; confidence interval calculation for risk probability estimates |

Integration of Biodiversity and Health Metrics

The emerging field of integrated biodiversity and health metrics represents a critical advancement in ecological risk assessment. Despite over a decade of progressive commitments from parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, integrated biodiversity and health indicators and monitoring mechanisms remain limited [6]. The recent adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the Global Action Plan on Biodiversity and Health provide renewed impetus to develop metrics that simultaneously address biodiversity loss and environmental determinants of human health.

Integrated science-based metrics are comprehensive measures that combine data from multiple scientific disciplines to assess complex issues holistically. These metrics integrate ecological, health, and socio-economic data to provide nuanced understanding of the interplay between systems [6]. They are designed for policy relevance, supporting informed decision-making by offering scalable, evidence-based insights that reflect real-world conditions and trends. Such metrics can quantify nature's role as a determinant of health and describe causal links between biodiversity and human health outcomes.

The One Health approach exemplifies this integrated perspective, defined as "an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of humans, animals, plants and ecosystems" [6]. This approach recognizes the close linkages and interdependencies between the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment. Similarly, planetary health emphasizes the health of human civilization and the state of the natural systems on which it depends [6]. Both frameworks provide conceptual foundations for developing metrics that simultaneously capture biodiversity conservation and public health objectives.

The escalating global biodiversity crisis, marked by findings that over a quarter of species assessed on the IUCN Red List face a high risk of extinction, demands robust scientific frameworks for environmental protection [7]. Two dominant, yet often disconnected, paradigms have emerged: Traditional Nature Conservation Assessment (NCA) and Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA). The former, exemplified by the work of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), focuses on species, habitats, and threat status [8]. The latter, commonly used by environmental protection agencies, emphasizes quantifying the risks posed by specific physical and chemical stressors to ecosystem structure and function [8]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical contrast of these two approaches, framing them within a broader thesis on ecological risk assessment for biodiversity protection research. It is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear understanding of their core principles, methodologies, and the imperative to bridge these disciplinary divides for more effective conservation outcomes.

Philosophical and Methodological Foundations

The divergence between NCA and ERA begins with their foundational purposes and cultural approaches to environmental science.

Traditional Nature Conservation Assessment (NCA) is primarily a signaling and awareness-raising system. Its core mission is to detect symptoms of endangerment and classify species according to their threat of extinction, even when the specific threatening process is not fully understood or identified [8]. It is inherently taxon-specific, often focusing on species with high conservation appeal or specific protection value, such as tigers, butterflies, or birds [8] [7]. A central tool of NCA is the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, which employs semi-quantitative, criterion-based thresholds to categorize species into threat levels (e.g., Vulnerable, Endangered, Critically Endangered) [8]. This approach is inherently value-driven, prioritizing species based on rarity, endemicity, cultural significance, or ecological function.

Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA), in contrast, is a decision-support tool designed to provide a structured, quantitative framework for evaluating the likelihood of adverse ecological effects resulting from human activities, particularly exposure to contaminants [8] [9]. It is stressors-oriented, focusing on specific chemical or physical agents such as pesticides, heavy metals, or land use changes. ERA typically relies on extrapolation from laboratory toxicity data on a limited set of test species to predict risks to broader ecosystem services and functions [8]. Its strength lies in its scientific rigor and transparency, systematically separating the scientific process of risk analysis from the socio-economic process of risk management [9]. This allows for objective, defensible evaluations that balance ecological protection with other considerations.

Table 1: Foundational Contrasts Between NCA and ERA.

| Aspect | Traditional Nature Conservation Assessment (NCA) | Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Signal endangerment; raise awareness for protection [8] | Quantify the likelihood of adverse impacts from stressors [9] |

| Core Focus | Species, habitats, and ecosystems of conservation value [8] | Chemical, physical, and biological stressors [8] |

| Key Tool | IUCN Red List (threat categories) [8] | Risk characterization (e.g., PEC/PNEC, HQ) [9] |

| Knowledge Foundation | Field ecology, population surveys, threat mapping [7] | Ecotoxicology, chemistry, statistics, extrapolation modeling [8] |

| Treatment of Uncertainty | Classifies threat even if cause is unknown [8] | Explicitly characterizes uncertainty in risk estimates [9] |

Operational Frameworks and Key Metrics

The application of NCA and ERA involves distinct operational workflows, data requirements, and output metrics.

The NCA Workflow and Metrics

The NCA process is often iterative and observational. It begins with species population and habitat data collection through field surveys, camera traps, bioacoustics, and citizen science [7] [10]. This data is analyzed against the IUCN Red List Criteria, which include quantitative thresholds for population size, geographic range, and rate of decline [8]. The outcome is a conservation status classification. Subsequent actions involve developing species-specific or habitat-specific recovery plans, which may include habitat protection, community engagement, and threat mitigation [7]. Key metrics include population viability, habitat connectivity, and the Red List Index, which tracks changes in aggregate extinction risk over time.

The ERA Framework and Process

ERA follows a more linear and prescriptive process, typically broken into two main phases: Preparation and Assessment, followed by reporting [9]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and other bodies formalize this into a sequence of problem formulation, exposure and effects analysis, and risk characterization.

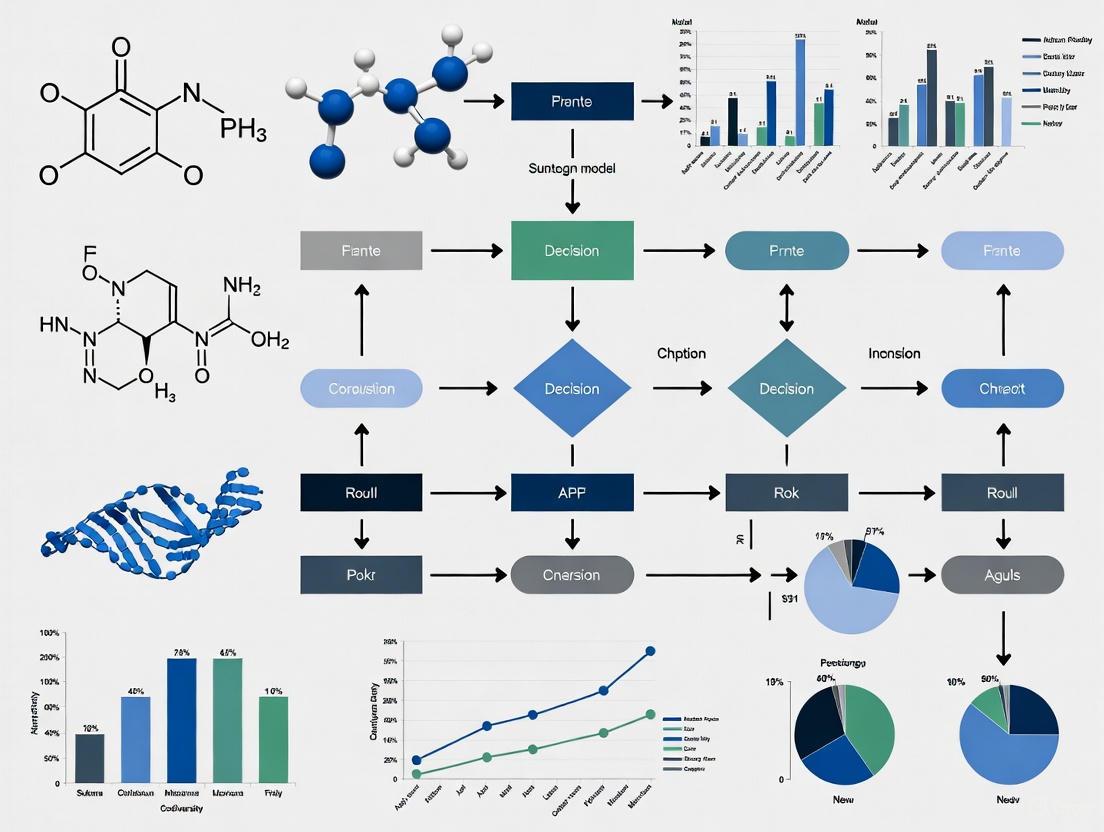

Diagram 1: The core ERA process, from problem formulation to risk management.

- Step 1: Problem Formulation: This stage defines the scope, goals, and boundaries of the assessment. It identifies the potential stressors and the specific environmental values (e.g., a fish population, water quality) and indicators to be protected [9].

- Step 2: Exposure Analysis: This step estimates the concentration, duration, and frequency of contact between the identified stressor and the ecological components of concern. It involves environmental fate and transport modeling and chemical monitoring (CM) [9].

- Step 3: Hazard (Effects) Analysis: This phase evaluates the inherent toxicity of the stressor. It involves dose-response assessment, often using data from single-species laboratory tests, and may incorporate Biological Effect Monitoring (BEM) to identify early-warning biomarkers of exposure [9].

- Step 4: Risk Characterization: This is the integration phase, where exposure and hazard data are combined to produce a quantitative estimate of risk (e.g., a Risk Quotient). It explicitly states the likelihood, severity, and spatial/temporal scale of potential adverse effects, along with all associated uncertainties [9].

- Step 5: Risk Management: Although a management step, it is informed by the scientific assessment. Here, stakeholders and regulators develop strategies to mitigate or prevent identified risks, balancing ecological, economic, and social factors [9].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Data and Monitoring Methods in ERA.

| Category | Method/Indicator | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Monitoring | Direct measurement of contaminants (e.g., LC-MS, GC-MS) | Quantifies known contaminant levels in water, soil, and sediment [9]. |

| Bioaccumulation Monitoring | Tissue residue analysis in biota (e.g., fish) | Examines contaminant levels in organisms; assesses biomagnification risk through food webs [9]. |

| Biological Effect Monitoring | Biomarkers (e.g., EROD activity, DNA damage) | Identifies early sub-lethal biological changes indicating exposure and effect [9]. |

| Ecosystem Monitoring | Biodiversity indices, species composition | Evaluates ecosystem health via population densities and community structure [9]. |

Critical Analysis: Bridging the Disciplinary Gap

The separation between NCA and ERA creates significant gaps that can hamper comprehensive biodiversity protection [8] [11].

- The Problem of "Unknown Causes" in NCA: NCA can flag a species as threatened using general threat categories like "agriculture" or "pesticides," but it often lacks the mechanistic detail to identify the specific causative agents or exposure pathways [8]. This makes it difficult to design targeted remediation actions. For example, knowing that a pollinator decline is linked to "agricultural intensification" is less actionable than knowing it is driven by a specific insecticide at a particular concentration.

- The Problem of "Statistical Species" in ERA: Standard ERA treats species as statistical entities in laboratory tests or as components of an ecosystem service. It frequently fails to account for specific life-history traits, rare species, endemic species, or species with high conservation value [8]. A protective standard derived for a common laboratory species may not safeguard a rare, more sensitive species that is the focus of NCA.

- The Way Forward: Integration: Bridging this gap requires multidisciplinary effort. Promising pathways include:

- Developing ERA for Threatened Species: Using the IUCN Red List to prioritize species for targeted ecotoxicological testing, moving beyond standard test species [8].

- Incorporating ERA into Conservation Planning: Using risk assessment principles to evaluate the impacts of specific development projects on threatened species and important biodiversity areas, as seen in spatial risk assessments for infrastructure projects [12].

- Adopting a Functional Biodiversity Approach: Linking ecosystem service protection from ERA with the species-focused priorities of NCA, potentially through a tiered assessment approach [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Bridging NCA and ERA in field research and monitoring requires a suite of advanced tools for data collection and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Integrated Field Studies.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Integrated Assessment |

|---|---|

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) | Non-invasive sampling to detect species presence (for NCA) and potential exposure to contaminants [10]. |

| Camera Traps & Bioacoustics | Monitors population density and behavior of umbrella/target species (NCA) and can indicate behavioral responses to stressors [10]. |

| Passive Sampling Devices | Measures time-weighted average concentrations of bioavailable contaminants in water or soil for exposure analysis in ERA [9]. |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Reagents for measuring biochemical biomarkers (e.g., acetylcholinesterase inhibition, oxidative stress) in field-sampled organisms for BEM in ERA [9]. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Elucidates food web structure (NCA) and tracks the bioaccumulation and biomagnification of specific contaminants (ERA) [9]. |

| 2',3'-Didehydro-3'-deoxy-4-thiothymidine | 2',3'-Didehydro-3'-deoxy-4-thiothymidine, CAS:5983-08-4, MF:C10H12N2O3S, MW:240.28 g/mol |

| Safingol Hydrochloride | Safingol Hydrochloride, CAS:139755-79-6, MF:C18H40ClNO2, MW:338.0 g/mol |

The contrasting paradigms of Traditional Nature Conservation Assessment and Ecological Risk Assessment are not in opposition but are complementary. NCA provides the "what" and "where" of conservation priorities—which species and ecosystems are most at risk. ERA provides the "why" and "how much"—the causative agents and the quantitative likelihood of harm. The future of effective biodiversity protection research lies in the conscious integration of these two worlds. By embedding the mechanistic, quantitative rigor of ERA into the priority-driven mission of NCA, researchers and environmental managers can develop more targeted, effective, and defensible strategies to halt biodiversity loss and restore ecosystems in an increasingly stressed world.

The problem formulation stage constitutes the critical foundation of the Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) process, establishing its scope, purpose, and direction. As defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), this initial phase involves identifying the stressors of potential concern, the ecological receptors that may be affected, and developing conceptual models that predict the relationships between them [13]. Within the context of biodiversity protection research, a rigorously executed problem formulation stage ensures that assessments are targeted toward protecting valued ecological entities and functions, particularly when evaluating the impacts of stressors such as manufactured chemicals, physical habitat disturbances, or biological agents. This phase transforms broad environmental concerns into a structured scientific investigation by defining clear assessment endpoints and creating analytical frameworks that guide the entire risk assessment process [14]. The outputs of problem formulation directly inform the analysis phase, where exposure and effects are characterized, and ultimately support risk characterization that quantifies the likelihood and severity of adverse ecological effects [13]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this foundational stage is essential for designing studies that yield actionable insights for environmental protection and regulatory decision-making.

Core Components of Problem Formulation

The problem formulation stage integrates three core components that collectively establish the assessment framework. These components ensure the ERA addresses relevant ecological values and produces scientifically defensible results for biodiversity protection.

Identification of Stressors

Stressors are defined as any physical, chemical, or biological entities that can induce adverse effects on ecological receptors [13]. In the problem formulation phase, stressor identification involves characterizing key attributes that influence their potential impact, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Characteristics for Stressor Identification in ERA

| Characteristic | Description | Examples for Biodiversity Context |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Categorical classification of the stressor | Chemical (pesticides, pharmaceuticals), Physical (habitat fragmentation, sedimentation), Biological (invasive species, pathogens) [13] |

| Intensity | Concentration or magnitude of the stressor | Chemical concentration (e.g., mg/L), Physical force (e.g., noise decibels, sediment load) [13] |

| Duration | Time period over which exposure occurs | Short-term (acute pulse exposure), Long-term (chronic exposure) [13] |

| Frequency | How often the exposure event occurs | One-time, Episodic (e.g., seasonal pesticide application), Continuous (e.g., effluent discharge) [13] |

| Timing | Temporal occurrence relative to biological cycles | Relative to seasons, sensitive life stages (e.g., reproduction, larval development) [13] |

| Scale | Spatial extent and heterogeneity | Localized (e.g., contaminated site), Landscape-level (e.g., watershed pollution) [13] |

Physical stressors warrant particular attention in biodiversity contexts as they often directly eliminate or degrade portions of ecosystems [15]. Examples include logging activities, construction of dams, removal of riparian habitat, and land development. A critical consideration is that physical stressors often trigger secondary effects that cascade through ecosystems; for instance, riparian habitat removal can lead to changes in nutrient levels, stream temperature, suspended sediments, and flow regimes [15]. Climate change represents another significant physical stressor with far-reaching implications for biodiversity protection, altering habitat conditions and species survival thresholds.

Identification of Ecological Receptors

Ecological receptors are the components of the ecosystem that may be adversely affected by stressors, ranging from individual organisms to entire communities and ecosystems. For biodiversity protection, selecting appropriate receptors involves prioritizing species, communities, or ecological functions that are both vulnerable to exposure and valued for conservation. According to the EPA's Guidelines for Ecological Risk Assessment, the selection process should consider several factors: the ecological value of potential receptors (e.g., keystone species, endangered species), their demonstrated or potential exposure to stressors, and their sensitivity to those stressors [13]. Life stage is particularly important when characterizing receptor vulnerability, as adverse effects may be most significant during critical phases such as early development or reproduction [13]. For instance, fish may face significant risk if unable to find suitable nesting sites during reproductive phases, even when water quality remains high and food sources are abundant [13].

Development of Conceptual Models

Conceptual models provide a visual representation and written description of the predicted relationships between ecological entities and the stressors to which they may be exposed [13]. These models illustrate the pathways through which stressors affect receptors and help identify potential secondary effects that might otherwise be overlooked. A well-constructed conceptual model includes several key elements: stressor sources, exposure pathways, ecological effects, and the ecological receptors evaluated. The model should depict both direct relationships (e.g., chemical exposure directly causing mortality in fish) and indirect relationships (e.g., habitat modification reducing food availability, leading to reduced reproductive success). According to the EPA, conceptual models are essential for ensuring assessments consider the complete sequence of events that link stressor release to ultimate ecological impacts [13]. The following diagram illustrates a generalized conceptual model for ecological risk assessment:

Diagram 1: Conceptual Model for Ecological Risk Assessment

Methodologies for Problem Formulation

Implementing the problem formulation stage requires systematic approaches to gather and evaluate information. The following methodologies provide structured protocols for identifying stressors, receptors, and developing conceptual models.

Stressor Characterization Protocol

Comprehensive stressor identification involves a multi-step process that integrates multiple data sources. The following workflow outlines a standardized protocol for stressor characterization:

Diagram 2: Stressor Identification and Characterization Workflow

Procedural Details:

- Step 1: Document Stressor Sources - Identify all potential anthropogenic activities (e.g., industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, land development) and natural processes that may introduce stressors into the environment. Utilize site monitoring data, historical records, and aerial imagery.

- Step 2: Characterize Stressor Properties - Classify stressors according to the characteristics outlined in Table 1. For chemical stressors, this includes documenting chemical properties (e.g., persistence, bioaccumulation potential); for physical stressors, document magnitude and extent.

- Step 3: Identify Exposure Pathways - Determine potential routes through which stressors may reach ecological receptors (e.g., waterborne transport, dietary uptake, direct contact). The EPA emphasizes that exposure represents "contact or co-occurrence between a stressor and a receptor" [13].

- Step 4: Determine Spatial/Temporal Patterns - Map the spatial distribution of stressors and characterize their timing relative to sensitive biological periods (e.g., breeding seasons, migration patterns).

- Step 5: Identify Potential Secondary Stressors - Recognize that initial disturbances may cause primary effects, but secondary stressors might also occur as natural counterparts [15]. For example, land development may decrease the frequency but increase the severity of fires or flooding in a watershed.

Receptor Selection Protocol

Selecting appropriate ecological receptors involves a prioritization process that balances ecological significance with practical assessment considerations. The methodology includes these key steps:

- Compile Candidate Receptor List - Identify potential receptors based on known or expected presence in the assessment area, focusing on species, communities, or functions critical to biodiversity.

- Apply Screening Criteria - Evaluate candidates against three primary criteria:

- Ecological Significance: Keystone species, endangered species, foundation species, and species critical to ecosystem function.

- Exposure Potential: Likelihood of contact with stressors based on habitat use, trophic position, and behavioral patterns.

- Sensitivity: Demonstrated or predicted vulnerability to specific stressors based on life history traits or previous toxicological studies.

- Consider Organizational Levels - Recognize that effects may manifest at different biological levels (individual, population, community, ecosystem) and select receptors accordingly. As noted in critical reviews of ERA, "level of biological organization is often related negatively with ease at assessing cause-effect relationships" but "positively with sensitivity to important negative and positive feedbacks" [14].

- Finalize Receptor List - Select a manageable set of receptors that represent key ecosystem components and functions, ensuring they align with assessment endpoints and management goals.

Conceptual Model Development Protocol

Developing a comprehensive conceptual model requires integrating information about stressors, receptors, and ecosystem processes:

- Define Ecosystem Boundaries - Establish the spatial and temporal boundaries of the assessment, ensuring they encompass complete exposure pathways.

- Identify Stressor-Receptor Relationships - For each stressor-receptor combination, diagram potential exposure pathways and expected ecological responses.

- Incorporate Ecosystem Processes - Include relevant ecological processes (e.g., nutrient cycling, predation, competition) that may influence stressor effects or create indirect pathways.

- Define Assessment and Measurement Endpoints - Clearly link model components to specific assessment endpoints (what is to be protected) and measurement endpoints (what will be measured) [14]. This distinction is crucial as measurement endpoints (e.g., LC50, NOAEC) are often used to infer effects on assessment endpoints (e.g., ecosystem function, biodiversity).

- Validate Model Completeness - Review the model with subject matter experts to ensure all plausible pathways are included and the representation reflects current ecological understanding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Conducting effective problem formulation requires specific analytical tools and resources. The following table catalogues key research reagents and methodologies essential for this ERA stage.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Problem Formulation in ERA

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Problem Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Sampling Kits | Water sampling kits, sediment corers, plankton nets, soil sampling equipment | Collect environmental media for stressor characterization and exposure assessment |

| Biological Survey Equipment | Aquatic macroinvertebrate samplers, mist nets, camera traps, vegetation quadrats | Document receptor presence/absence, population density, and community composition |

| GIS and Spatial Analysis Tools | Geographic Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing software, habitat mapping tools | Delineate assessment boundaries, map stressor distribution, and identify receptor habitats |

| Ecological Database Access | Toxicity databases (e.g., ECOTOX), species habitat requirements, ecological trait databases | Support stressor-receptor linkage analysis and identify sensitive species |

| Statistical Analysis Software | R, Python with ecological packages, PRIMER, PC-ORD | Analyze historical monitoring data and identify stressor-response relationships |

| Floramultine | Floramultine | Floramultine is a natural isoquinoline alkaloid that inhibits acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE). For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Saframycin G | Saframycin G, CAS:92569-02-3, MF:C29H30N4O9, MW:578.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Considerations in Problem Formulation

Modern ecological risk assessment, particularly within biodiversity protection research, requires addressing several complex challenges during problem formulation.

Addressing Multiple Stressor Interactions

Environmental systems typically face multiple simultaneous stressors that can interact in complex ways. During problem formulation, assessors should identify potential stressor interactions, which may be:

- Additive: Combined effect equals the sum of individual effects.

- Antagonistic: Combined effect is less than the sum of individual effects.

- Synergistic: Combined effect exceeds the sum of individual effects [14].

The conceptual model should represent these potential interactions, as combined stressors may have effects that are substantially different from single stressors, and cumulative exposure over time may result in unexpected impacts [13].

Cross-Level Ecological extrapolation

A fundamental challenge in ERA is the mismatch between measurement endpoints (what is measured) and assessment endpoints (what is to be protected) [14]. Problem formulation should explicitly address how effects measured at one level of biological organization (e.g., cellular responses in individual organisms) predict effects at higher levels (e.g., population viability, community structure). The conceptual model can facilitate this by illustrating connections across organizational levels and identifying critical extrapolation points.

Landscape-Scale Assessment Considerations

For biodiversity protection, problem formulation must increasingly address landscape-scale processes. This requires:

- Defining assessment boundaries that encompass ecologically meaningful units (e.g., watersheds, habitat patches, migration corridors).

- Considering metapopulation dynamics and source-sink relationships for receptor populations.

- Incorporating landscape connectivity and fragmentation as potential stressors or modifying factors.

- Evaluating cumulative effects across multiple stressor sources distributed throughout the landscape.

By addressing these advanced considerations during problem formulation, risk assessors can develop more comprehensive and ecologically relevant assessments that effectively support biodiversity protection goals. The structured approaches outlined in this guide provide researchers and drug development professionals with methodologies to establish scientifically defensible foundations for ecological risk assessment, ultimately contributing to more effective conservation outcomes and environmental decision-making.

Biodiversity, the complex variety of life on Earth, is experiencing unprecedented declines across all ecosystems. This whitepaper synthesizes current scientific knowledge on the primary threats to biodiversity, categorizing them into chemical, physical, and biological stressors. These stressors increasingly interact in complex, nonlinear ways, driving potentially irreversible ecological tipping points. Recent meta-analyses reveal that chemical pollution has emerged as a particularly severe threat, now affecting approximately 20% of endangered species and in many cases representing the primary driver of extinction risk [16]. Understanding these interacting stressor dynamics is fundamental to developing effective ecological risk assessment frameworks and conservation strategies aimed at protecting global biodiversity.

Biodiversity encompasses the genetic diversity within species, the variety of species themselves, and the diversity of ecosystems they form [17]. This biological complexity provides critical ecosystem services valued at an estimated $125-145 trillion annually, including climate regulation, pollination, water purification, and sources for pharmaceuticals [18] [19]. However, human activities have accelerated extinction rates to 10-100 times above natural background levels [18], with comprehensive analyses indicating that land-use intensification and pollution cause the most significant reductions in biological communities across multiple taxa [20].

Stressors to biodiversity are usefully categorized as:

- Chemical Stressors: Synthetic compounds including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, industrial chemicals, and heavy metals

- Physical Stressors: Modifications to habitat structure, climate parameters, and landscape connectivity

- Biological Stressors: Non-native species introductions and pathogen spread

These categories frequently interact, creating cumulative impacts that complicate traditional risk assessment approaches focused on single stressors [21]. The following sections detail each stressor category, providing quantitative data on their impacts and methodologies for their study.

Chemical Stressors

Impact Mechanisms and Quantitative Assessment

Chemical pollution represents a planetary-scale threat to biodiversity, with over 350,000 synthetic chemicals currently in use and production projected to triple by 2050 compared to 2010 levels [16]. Traditional risk assessment paradigms that rely on linear dose-response models critically oversimplify the complex, nonlinear interactions between chemical pollutants and ecosystems [21]. These impacts often exhibit threshold effects, hysteresis, and potentially irreversible regime shifts rather than gradual, predictable responses [21].

Table 1: Key Chemical Stressors and Their Documented Impacts on Biodiversity

| Stressor Category | Key Example Compounds | Primary Impact Mechanisms | Documented Ecological Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Chemicals | Pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers | Disruption of endocrine systems, neurotoxicity, nutrient loading leading to eutrophication | Oxygen depletion in freshwater systems [22], reduction in soil fauna diversity [20] |

| Industrial Compounds | Heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), plastic additives | Bioaccumulation in tissues, biomagnification through food webs, direct toxicity | 70% increase in methylmercury in spiny dogfish from combined warming and herring depletion [21] |

| Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products | Antibiotics, synthetic hormones, antimicrobials | Disruption of reproductive functions, alteration of microbial communities | Emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in environmental bacteria [18] |

| Plastic Pollution | Macroplastics, microplastics, nano-plastics | Physical entanglement, ingestion, leaching of additives, ecosystem engineering | 14 million tons annual ocean input; 600 million tons cumulative by 2040 including microplastics [23] |

Recent research demonstrates that low-level chemical pollution puts nearly 20% of endangered species at risk, making it the leading cause of decline for many threatened species [16]. These chemicals persist and bioaccumulate across interconnected ecosystems, posing significant threats to global biodiversity and ecosystem stability [21]. The combined effects of various chemical stressors with other environmental pressures heighten the probability of crossing ecological tipping points across ecosystems worldwide [21].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Chemical Impacts

Advanced methodologies are required to detect and quantify the complex impacts of chemical stressors on biodiversity:

Non-Target Screening (NTS) with Chemical Fingerprinting

- Purpose: Comprehensive identification of unknown chemical contaminants in environmental samples

- Methodology: High-resolution mass spectrometry coupled with liquid or gas chromatography separates and detects thousands of chemical features in water, sediment, or tissue samples [21]. In Chebei Stream, Guangzhou, NTS-based chemical fingerprints effectively traced pollutant sources in complex mixtures [21] [16].

- Data Analysis: Suspect screening against compound libraries and nontarget identification using computational mass spectrometry tools to characterize unknown compounds.

Mixture Toxicity Testing with Multi-Stressor Designs

- Purpose: Quantify interactive effects of multiple chemical and non-chemical stressors

- Experimental Design: Full factorial or response surface designs that expose model organisms to gradients of chemical stressors (e.g., zinc, copper) combined with other stressors (e.g., temperature, salinity) [21] [22].

- Endpoint Measurement: Sublethal responses including gene expression changes, metabolic profiles, reproductive output, and behavioral alterations in addition to traditional mortality endpoints [21].

Environmental DNA (eDNA) Metabarcoding for Community Assessment

- Purpose: Detect biodiversity changes in response to chemical exposure at ecosystem scale

- Sampling Protocol: Collection of water, sediment, or soil samples from reference and impacted sites, filtration to capture DNA, extraction, and amplification using primer sets specific to target taxa (e.g., invertebrates, fish, bacteria) [16].

- Bioinformatics: High-throughput sequencing followed by sequence processing, clustering into operational taxonomic units (OTUs), and taxonomic assignment using reference databases [22].

Physical Stressors

Climate Change and Habitat Alteration

Physical stressors encompass modifications to the physical environment that directly impact species survival and ecosystem function. Climate change represents a particularly pervasive physical stressor, with 2024 confirmed as the hottest year in history, reaching 1.60°C above pre-industrial levels [23]. These temperature increases are not uniform globally, with the Arctic warming at more than twice the global average [23].

Table 2: Physical Stressors and Their Documented Impacts on Biodiversity

| Stressor Category | Specific Stressors | Impact Mechanisms | Taxa-Specific Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | Rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, ocean acidification | Range shift, phenological mismatches, physiological stress | Invertebrate richness declines with warming; fish richness shows positive trend [22] |

| Habitat Destruction & Fragmentation | Deforestation, urbanization, infrastructure development | Direct habitat loss, population isolation, reduced genetic diversity | Mammal, bird, and amphibian populations declined 68% on average 1970-2016 [23] |

| Hydrological Modification | Flow alteration, channelization, sediment accumulation | Disruption of aquatic habitat structure, altered flow regimes | Negative impact on invertebrate and fish richness [22] |

| Sea Level Rise | Coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion, habitat submersion | Loss of coastal habitats, changes in salinity gradients | Submergence of low-lying ecosystems; 35% global wetland loss since 1970 [18] |

Meta-analysis of 3,161 effect sizes from 624 publications found that land-use intensification resulted in large reductions in soil fauna communities, especially for larger-bodied organisms [20]. Habitat fragmentation divides populations into smaller, isolated groups, reducing reproductive opportunities and increasing vulnerability to environmental fluctuations [24]. The combined impact of these physical stressors significantly compromises ecosystem resilience and increases the likelihood of catastrophic state shifts [21].

Methodologies for Physical Stressor Research

Landscape Fragmentation Analysis

- Purpose: Quantify habitat connectivity and its effects on population viability

- Methodology: GIS-based analysis of land cover data to calculate patch size, inter-patch distance, and landscape resistance metrics [25]. Coupled with field surveys of target species abundance and genetic diversity.

- Tools: Circuit theory applications, least-cost path analysis, and graph theory applied to landscape connectivity.

Thermal Stress Experiments

- Purpose: Determine species-specific vulnerability to climate warming

- Protocol: Controlled mesocosm studies with temperature gradients mirroring projected climate scenarios. Measurement of physiological responses (metabolic rates, thermal tolerance limits), demographic parameters (survival, reproduction), and behavioral adaptations [22] [19].

- Field Validation: Long-term monitoring of population responses to natural temperature variation using data loggers and repeated surveys.

Sediment Impact Assessment

- Purpose: Evaluate effects of fine sediment accumulation on aquatic ecosystems

- Methodology: Standardized sediment traps deployed in river systems to quantify deposition rates [22]. Paired with benthic community sampling using Surber samplers or kick nets across sediment gradients.

- Statistical Analysis: Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) to relate sediment metrics to biodiversity indices while accounting for confounding environmental variables [22].

Biological Stressors

Invasive Species and Disease Dynamics

Biological stressors include non-native species introductions and pathogen spread that disrupt native biodiversity. Invasive alien species contribute to 60% of recorded global extinctions and cause an estimated $423 billion in annual economic damage [18]. The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services reports that human activities have introduced more than 37,000 non-native species to new environments [17].

Invasive species impact native biodiversity through multiple mechanisms:

- Competitive Exclusion: Non-native plants and animals often outcompete native species for resources such as light, space, nutrients, and food [25].

- Predation Pressure: Introduced predators can devastate native prey species that lack evolved defense mechanisms [25].

- Disease Introduction: Pathogens carried by non-native species can decimate native populations, as exemplified by chestnut blight that functionally eliminated American chestnut trees from eastern North American forests [25].

- Ecosystem Engineering: Some invasive species fundamentally alter habitat structure, as seen with kudzu dramatically overgrowing landscapes in the southern United States [25].

Climate change is exacerbating biological stressors by enabling the poleward and altitudinal expansion of invasive species ranges [19]. For example, warming ocean temperatures are facilitating the northward expansion of tropical lionfish in the Atlantic, threatening native fish communities [19].

Research Protocols for Biological Stressor Impacts

Invasive Species Impact Assessment

- Purpose: Quantify the ecological impacts of non-native species on native communities

- Methodology: Paired field surveys comparing invaded and uninvaded habitats, measuring parameters including native species richness, abundance, biomass, and ecosystem processes [25].

- Experimental Manipulation: Controlled removal experiments to document community recovery potential and identify mechanisms of impact.

Pathogen Surveillance Systems

- Purpose: Monitor emerging wildlife diseases and their impacts on vulnerable species

- Protocols: Systematic health assessments of wild populations, including non-invasive sampling (feces, saliva, feathers/fur) combined with molecular detection methods (PCR, metagenomics) [18].

- Disease Risk Modeling: Integration of pathogen prevalence data with environmental and host population parameters to predict outbreak risks under different climate scenarios.

Stressor Interactions and Nonlinear Dynamics

Complex Response Patterns

A critical frontier in biodiversity risk assessment involves understanding how multiple stressors interact to produce nonlinear ecological responses that cannot be predicted from single-stressor effects [21]. Evidence from cross-continental studies demonstrates that pollutant impacts on ecosystems often exhibit significant nonlinear characteristics, including thresholds, hysteresis, and potentially irreversible regime shifts [21].

Several documented cases illustrate these complex interactions:

- Coral Reef Systems: Chemical pollution undermines coral resilience, diminishing their capacity to withstand ocean acidification and accelerating transitions to degraded, algae-dominated states [21].

- Freshwater Ecosystems: Elevated zinc and copper levels, particularly when combined with high wastewater exposure, disproportionately drive biodiversity declines in rivers, even after adjusting for habitat quality [21].

- Marine Food Webs: Non-additive interactions among climate warming, overfishing, and methylmercury bioaccumulation have been documented over three decades in the Gulf of Maine, where a 1°C rise in seawater temperature increased MeHg concentrations in Atlantic cod by 32% [21].

These interactive effects necessitate a paradigm shift from single-stressor risk assessment toward integrated frameworks that capture the complex, nonlinear dynamics in real-world ecosystems under multiple pressures [21].

Integrated Assessment Framework

Researchers have proposed a four-component framework to address stressor interactions:

- Hierarchical Monitoring Systems combining chemical, biological, and ecological data to track pollutant effects across ecosystems using tools including NTS, molecular biomarkers, and eDNA metabarcoding [21] [16].

- Multi-Stressor Assessments employing advanced statistical methods including machine learning to quantify interactive effects and identify early warning signals of ecological transitions [21] [22].

- Policy Integration embedding real-time early warning systems based on remote sensing and biosensors into regulatory frameworks to enable timely interventions [21] [16].

- Technology Development creating smart biosensors for real-time detection of stress in sentinel species and remote sensing tools for large-scale resilience monitoring [21].

The conceptual relationship between stressor interactions and biodiversity outcomes can be visualized as follows:

The Researcher's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Cutting-edge biodiversity stressor research requires specialized reagents and technologies designed to detect and quantify subtle ecological changes:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Biodiversity Stressor Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Application | Key Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Assessment Tools | eDNA extraction kits, species-specific primers, metabarcoding arrays | Detection of biodiversity changes and invasive species | Sensitive monitoring of community composition without visual observation [16] |

| Chemical Analysis Reagents | LC-MS grade solvents, derivatization reagents, stable isotope standards | Non-target screening and chemical fingerprinting | Identification and quantification of unknown environmental contaminants [21] |

| Biosensor Systems | Antibody-based test strips, nanoparticle-based sensors, enzyme-linked assays | Real-time stress detection in sentinel species | Field-based detection of physiological stress responses [21] [16] |

| Remote Sensing Platforms | Multispectral sensors, LiDAR, thermal imaging cameras | Large-scale habitat and ecosystem monitoring | Detection of vegetation stress, habitat loss, and ecological changes at landscape scales [21] [16] |

| Piribedil Hydrochloride | Piribedil Hydrochloride, CAS:78213-63-5, MF:C16H19ClN4O2, MW:334.80 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Bakuchicin | Bakuchicin, CAS:4412-93-5, MF:C11H6O3, MW:186.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Methodological Workflow for Integrated Stressor Assessment

A comprehensive methodological approach for assessing multiple stressor impacts incorporates both field and laboratory components:

Biodiversity faces unprecedented threats from interacting chemical, physical, and biological stressors that drive complex, nonlinear ecological responses. Chemical pollution has emerged as a particularly severe threat, affecting approximately 20% of endangered species [16], while climate change and habitat destruction compound these impacts. Traditional single-stressor risk assessment approaches are inadequate for addressing these complex interactions [21].

Future conservation success depends on developing integrated monitoring frameworks that combine advanced technologies including eDNA metabarcoding, non-target screening, biosensors, and remote sensing with sophisticated statistical models capable of detecting early warning signs of ecological disruption [21] [16]. Such approaches will enable researchers and policymakers to identify ecological tipping points before they are crossed and implement more effective, timely interventions to protect global biodiversity.

Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) is defined as "the application of a formal process to (1) estimate the effects of human action(s) on a natural resource, and (2) interpret the significance of those effects in light of the uncertainties identified in each phase of the assessment process" [26]. Traditionally, ERA has served as a critical tool for evaluating the environmental impact of single chemical stressors, operating through a structured framework of problem formulation, analysis, and risk characterization [26]. This conventional approach has been instrumental in regulating hazardous waste sites, industrial chemicals, and pesticides [26]. However, the escalating challenges of biodiversity loss, climate change, and complex regional environmental threats have necessitated an evolution in ERA practice. The field is now transitioning from its chemical-centric origins toward comprehensive frameworks that integrate regional-scale analysis, climate adaptation planning, and biodiversity conservation principles [8] [27] [28]. This evolution represents a paradigm shift from evaluating isolated stressors to assessing cumulative impacts across landscapes and seascapes, thereby enabling more effective environmental policy and protection strategies in the face of global change.

The Traditional ERA Paradigm: Foundations and Limitations

The Core ERA Framework

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has established a standardized three-phase approach to ecological risk assessment, beginning with planning and proceeding through problem formulation, analysis, and risk characterization [26]. The problem formulation phase establishes the assessment's scope, identifying environmental stressors of concern and the specific ecological endpoints to be protected, such as the sustainability of fish populations or species diversity [26]. The analysis phase evaluates two key components: exposure (which organisms are exposed to stressors and to what degree) and ecological effects (the relationship between exposure levels and adverse impacts) [26]. Finally, risk characterization integrates these analyses to estimate the likelihood of adverse ecological effects and describes the associated uncertainties [26].

This framework has traditionally operated through tiered approaches, starting with conservative screening-level assessments and progressing to more refined evaluations when initial analyses indicate potential risk [14]. At its foundation, this process has relied heavily on laboratory-derived toxicity data from standard test species, using quotients of exposure and effect concentrations to determine risk levels [14].

Limitations of Single-Chemical Approaches

The traditional ERA paradigm faces significant limitations when addressing contemporary environmental challenges:

- Narrow Stressor Focus: Conventional ERA emphasizes chemical threats, often overlooking physical and biological stressors and their complex interactions [8].

- Inadequate Biodiversity Protection: The standard Species Sensitivity Distribution (SSD) approach treats species as statistical entities without considering rare, endemic, or specially protected species, creating a gap between risk assessment and conservation goals [8] [29].

- Scale Disconnect: Laboratory-based assessments on limited species have poor applicability to complex community and ecosystem-level responses in natural environments [14].

- Static Assessment Framework: Traditional ERA often fails to incorporate temporal dynamics, such as climate change effects or evolving land-use patterns [28].

The Evolution to Regional and Climate-Adaptive Frameworks

Incorporating Regional-Scale Assessments

The expansion of ERA to regional scales represents a significant evolution in the field, enabling assessment of cumulative impacts across watersheds, landscapes, and seascapes. This shift recognizes that environmental stressors operate across ecological boundaries that transcend political jurisdictions. Regional frameworks facilitate the evaluation of multiple interacting stressors, including land-use change, habitat fragmentation, and contaminant mixtures, providing a more holistic understanding of ecological risk [30].

The Mediterranean Regional Climate Change Adaptation Framework exemplifies this approach, defining "a regional strategic approach to increase the resilience of the Mediterranean marine and coastal natural and socioeconomic systems to the impacts of climate change" [27]. This framework acknowledges that climate impacts extend beyond traditional coastal zones, requiring integrated watershed management and multi-national cooperation [27]. Similarly, California's Regional Climate Adaptation Framework assists local and regional jurisdictions in managing sea level rise, extreme heat, wildfires, and other climate-related issues through coordinated planning [31].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Regional ERA Frameworks

| Framework | Geographic Scope | Key Stressors Addressed | Innovative Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean Adaptation Framework [27] | 21 countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea | Sea-level rise, coastal erosion, precipitation changes | Transboundary governance, integration of natural and socioeconomic systems |

| Southern California Adaptation Framework [31] | Southern California Association of Governments region | Sea-level rise, extreme heat, wildfires, drought | Multi-hazard vulnerability assessment, equity-focused planning |

| Xinjiang Ecosystem Service Risk Assessment [28] | Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China | Water scarcity, soil degradation, food production | Ecosystem service supply-demand imbalance analysis |

Integrating Climate Adaptation Principles

Climate-adaptive ERA frameworks incorporate forward-looking vulnerability assessments that project how climate change will alter exposure and sensitivity to both climatic and non-climatic stressors. The California Adaptation Planning Guide outlines a structured four-phase process for climate resilience planning: (1) Explore, Define, and Initiate; (2) Assess Vulnerability; (3) Define Adaptation Framework and Strategies; and (4) Implement, Monitor, Evaluate, and Adjust [32].

These frameworks emphasize adaptive capacity - the ability of ecological and human systems to prepare for, respond to, and recover from climate disruptions [32]. This represents a fundamental shift from static risk characterization to dynamic resilience building. The incorporation of climate equity principles ensures that historical inequities are addressed, allowing "everyone to fairly share the same benefits and burdens from climate solutions" [32].

Bridging ERA and Biodiversity Conservation

A critical advancement in modern ERA is the integration with Nature Conservation Assessment (NCA) approaches, particularly those developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). While traditional ERA focuses on chemical threats through cause-effect relationships, NCA emphasizes the protection of threatened species and ecosystems based on rarity, endemicity, and extinction risk [8]. Bridging these approaches requires:

- Inclusion of Rare and Endemic Species: Moving beyond statistical SSD approaches to specifically consider species with high conservation value [29].

- Ecosystem Services Integration: Evaluating risks not only to ecological structure but also to the functions that provide value to humans [29] [28].

- Spatially-Explicit Assessments: Mapping threats to protected species and habitats to enable targeted conservation interventions [8].

The evolving paradigm recognizes that "a multidisciplinary effort is needed to protect our natural environment and halt the ongoing decrease in biodiversity" that is "hampered by the fragmentation of scientific disciplines supporting environmental management" [8].

Methodological Advances in Modern ERA

Ecosystem Service Supply-Demand Risk Assessment

Contemporary ERA methodologies increasingly incorporate ecosystem service concepts to evaluate risks through the lens of human well-being and ecological sustainability. The novel approach of Ecosystem Service Supply-Demand Risk (ESSDR) assessment addresses limitations of traditional landscape pattern analysis by quantifying mismatches between ecological provision and human needs [28].

The ESSDR methodology employs several key metrics:

- Supply-Demand Ratio (ESDR): Quantifies the balance between ecosystem service provision and consumption [28].

- Supply Trend Index (STI): Measures temporal changes in service provision capacity [28].

- Demand Trend Index (DTI): Tracks evolving human demands on ecosystems [28].

Application in China's Xinjiang region demonstrated clear spatial differentiation, "with higher supply areas mainly located along river valleys and waterways, while demand is concentrated in the central cities of oases" [28]. This approach identified four risk bundles, enabling targeted management strategies for different regional contexts.

Multi-Level Biological Organization Assessment

Modern ERA recognizes that different assessment endpoints at varying biological organization levels provide complementary information. Research has revealed trade-offs across biological scales:

Table 2: Assessment Endpoints Across Biological Organization Levels

| Level of Organization | Advantages | Limitations | Common Assessment Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suborganismal [14] | High-throughput screening, early warning signals | Uncertain ecological relevance, distance from protection goals | Biomarker responses, gene expression |

| Individual [14] | Standardized tests, dose-response relationships | Limited population-level implications, artificial conditions | Survival, growth, reproduction |

| Population [14] | Demographic relevance, species-specific protection | Data intensive, limited number of assessable species | Abundance, extinction risk, decline trends |

| Community/Ecosystem [14] | Holistic assessment, functional endpoints | Complex causality, high variability | Species diversity, ecosystem services, functional integrity |

Next-generation ERA employs mathematical modeling approaches to extrapolate effects across biological levels, including mechanistic effect models that "compensate for weaknesses of ERA at any particular level of biological organization" [14]. The ideal approach "will only emerge if ERA is approached simultaneously from the bottom of biological organization up as well as from the top down" [14].

Spatially-Explicit and Probabilistic Methods

Advanced ERA methodologies incorporate spatial analysis and probabilistic techniques to better characterize real-world exposure scenarios and uncertainty. Spatially-explicit models "generate probabilistic spatially-explicit individual and population exposure estimates for ecological risk assessments" [30], enabling risk managers to identify hotspot areas and prioritize interventions.

These approaches are particularly valuable for assessing risks to threatened and endangered species, where "species-specific assessments" are conducted to evaluate "potential risk to endangered and threatened species from exposure to pesticides" [33]. The USEPA's endangered species risk assessment process incorporates "additional methodologies, models, and lines of evidence that are technically appropriate for risk management objectives" [33], including monitoring data and specialized exposure route evaluation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methods for Advanced ERA

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Modern Ecological Risk Assessment

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling Software | InVEST Model, GIS Spatial Analysis | Quantifying ecosystem service supply-demand dynamics, spatial analysis | [28] |

| Statistical Analysis | Self-Organizing Feature Map (SOFM), Probabilistic Risk Modeling | Identifying risk bundles, characterizing uncertainty | [14] [28] |

| Ecological Endpoints | Water Yield, Soil Retention, Carbon Sequestration, Food Production | Measuring ecosystem services and their balance with human demand | [28] |

| Extrapolation Tools | Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSD), Mechanistic Effect Models | Extrapolating from laboratory data to field populations and communities | [14] |

| Climate Projection Tools | Downscaled Climate Models, Sea-Level Rise Projections | Assessing future exposure scenarios under climate change | [31] [32] |

| Epoxyquinomicin B | Epoxyquinomicin B, CAS:175448-32-5, MF:C14H11NO6, MW:289.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Multifungin | Multifungin, CAS:39442-77-8, MF:C39H39BrClN3O5, MW:745.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implementation Workflow: From Assessment to Adaptive Management

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for implementing regional climate-adaptive ecological risk assessment:

Integrated ERA Workflow Diagram Title: Climate-Adaptive ERA Implementation Process

This workflow integrates traditional ERA components with climate-adaptive elements, emphasizing the critical role of monitoring and adaptive management in responding to changing environmental conditions [32] [30]. The process begins with comprehensive planning that engages diverse stakeholders to establish shared goals and scope [26] [32]. Vulnerability assessment expands traditional problem formulation to incorporate climate projections and socioeconomic factors [32]. Risk characterization integrates both quantitative estimates and qualitative description of uncertainties [26]. Adaptation planning identifies strategies that are not only effective for risk reduction but also feasible and equitable [32]. Implementation, monitoring, and evaluation form a continuous cycle that enables adaptive management - the critical feedback mechanism that allows ERA frameworks to respond to changing conditions and new information [32] [30].

The evolution of ecological risk assessment from single-chemical evaluation to regional and climate-adaptive frameworks represents a fundamental transformation in environmental protection strategy. This progression addresses critical gaps in traditional approaches by incorporating spatial explicitness, biodiversity conservation priorities, climate projections, and ecosystem service concepts. The integrated frameworks emerging across international jurisdictions recognize that effective environmental governance requires managing cumulative risks across landscapes and seascapes while preparing for future climate impacts.

Future directions in ERA development will likely include enhanced integration of technological advances such as remote sensing, environmental DNA analysis, and machine learning for pattern detection in complex ecological datasets. Additionally, continued effort to bridge the cultural and methodological divides between risk assessors and conservation biologists will be essential for developing unified approaches to biodiversity protection [8] [29]. As ecological risk assessment continues to evolve, its greatest contribution may be in providing a common analytical foundation for coordinating environmental management across traditional disciplinary and jurisdictional boundaries, ultimately enabling more proactive and resilient environmental governance in an era of global change.

Tools and Techniques: A Step-by-Step Guide to ERA Methodologies

Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) is a robust, systematic process for evaluating the likelihood of adverse ecological effects resulting from exposure to environmental stressors such as chemicals, physical alterations, or biological agents [34]. This scientific framework is fundamental for environmental decision-making, enabling the protection of biodiversity by balancing ecological concerns with social and economic considerations [34] [35]. The ERA process is characteristically iterative and separates scientific risk analysis from risk management, ensuring objective, transparent, and defensible evaluations [34]. Driven by policy goals and a precautionary approach, ERA can be applied prospectively to predict the consequences of proposed actions or retrospectively to diagnose the causes of existing environmental damage [34]. This guide details the three core technical phases of the ERA framework—Problem Formulation, Analysis, and Risk Characterization—providing researchers and scientists with the methodologies and tools necessary for rigorous biodiversity protection research.

Problem Formulation Phase

Problem Formulation is the critical first phase of an ERA, where the foundation for the entire assessment is established. It is a planning and scoping process that transforms broadly stated environmental protection goals into a focused, actionable assessment plan [36] [35]. During this phase, risk assessors, risk managers, and other stakeholders collaborate to define the problem, articulate the assessment's purpose, and ensure that the subsequent analysis will yield scientifically valid results relevant for decision-making [36]. An inadequate Problem Formulation can compromise the entire ERA, leading to requests for more data, miscommunication of findings, and delayed environmental protection measures [35].