Bridging the Data Gap: Advanced Strategies for Robust Chemical Assessments in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying, addressing, and validating data gaps in chemical hazard and risk assessment.

Bridging the Data Gap: Advanced Strategies for Robust Chemical Assessments in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying, addressing, and validating data gaps in chemical hazard and risk assessment. Covering foundational principles to advanced methodologies, it explores the application of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), chemical categories, and computational tools like QSAR and machine learning to fill critical information voids. The content also addresses practical troubleshooting for data quality and outlines frameworks for regulatory acceptance, offering a strategic pathway to more efficient, animal-free, and reliable chemical safety evaluations.

Understanding Data Gaps: Defining the Problem and Its Impact on Chemical Safety

What Constitutes a Data Gap in Chemical Hazard Assessment?

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a data gap in chemical hazard assessment? A data gap is incomplete information that prevents researchers from reaching a conclusive safety judgment about a chemical. This occurs when essential toxicological data for key hazard endpoints are missing, making it impossible to fully characterize the chemical's potential adverse effects on human health or the environment [1].

2. How do I identify a data gap in my assessment? You can identify data gaps by systematically checking available data against a list of toxicological endpoints of interest. The process involves determining if data is missing for entire endpoints (e.g., no carcinogenicity data), if the data is insufficient to characterize exposure, or if it does not cover all potentially affected media [1]. Tools like the EPA's GenRA provide data gap tables and matrices that visually represent data sparsity across source analogues and your target chemical, highlighting missing information in gray boxes [2].

3. What are the main types of data gaps? The primary types of data gaps can be categorized as follows:

- Missing Endpoint Data: A complete lack of experimental or predicted data for a standard hazard endpoint, such as genotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, or aquatic toxicity [3] [4].

- Insufficient Data Quality or Quantity: The existing data is inadequate to characterize exposure or hazard, for example, due to poor spatial or temporal representation in sampling studies [1].

- Lack of Data for Contaminants of Concern: Data is available for the primary chemical but not for its potential impurities, reaction byproducts, or degradation products, known as Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIAS) [5].

4. What methodologies can I use to fill a data gap without new animal testing? Several non-testing methodologies are accepted for filling data gaps:

- Read-Across and Chemical Categories: Grouping the target chemical with structurally similar chemicals (analogues) that have robust data and using that data to predict the properties of the target chemical [3] [6].

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSARs): Using computational models to predict a chemical's toxicity based on its molecular structure [3] [6].

- Exposure Modeling: Using models to predict contamination levels in the environment when empirical sampling data is missing [1].

- Weight-of-Evidence Approaches: Using a combination of predictive methods, existing low-quality data, and chemical grouping to build a case for a hazard conclusion [6].

5. Where can I find data to support a read-across argument? Data for read-across can be sourced from multiple public and commercial databases. A 2019 study highlighted that using multiple data sources is often necessary to successfully complete a hazard assessment [4]. Key sources include:

- EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard: Provides access to data from ToxCast and ToxRefDB [2] [6].

- Chemical Hazard Data Trusts: Platforms like ChemFORWARD aggregate and harmonize chemical hazard data from dozens of credible sources for screening and assessment [7].

- Other Secondary Databases: The scientific literature and various regulatory inventories.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My chemical has no in vivo toxicity data. Solution: Apply a read-across methodology using the OECD QSAR Toolbox.

- Define your target chemical by entering its SMILES notation or chemical structure.

- Identify a chemical category by profiling the chemical for relevant structural features and potential mechanisms of toxicity.

- Fill the data gap by using the experimental data from the tested analogues within the category to predict the hazard properties of your target chemical [3].

Problem: My chemical is part of a new class of compounds with few analogues. Solution: Use a QSAR model to generate a predictive estimate.

- Select an appropriate model, such as the EPA's ECOSAR for aquatic toxicity or OncoLogic for cancer potential, ensuring it is applicable to your chemical's class [6].

- Input the chemical structure into the model.

- Evaluate the prediction for reliability. The model will provide a quantitative estimate of toxicity (e.g., LC50 for fish), which can be used to fill the data gap for priority-setting [6].

Problem: I need to recommend new sampling to fill an environmental exposure data gap. Solution: Design a sampling plan with clear Data Quality Objectives (DQOs).

- State the principal study question the sampling will address (e.g., "What is the concentration of Chemical X in household tap water?").

- Define the spatial and temporal domains (e.g., "Samples from every household on Main Street, collected quarterly for one year").

- Specify the analytes and analytical methods (e.g., "Analyze for bromodichloromethane using EPA Method 551.1").

- Document QA/QC measures, including the use of duplicate samples, field blanks, and chain-of-custody procedures [1]. A well-defined plan ensures the collected data will be sufficient and reliable for your assessment.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conducting a Read-Across Assessment

- Objective: To predict the hazard of a data-poor chemical (target) using data from similar chemicals (source analogues).

- Workflow:

- Materials:

- OECD QSAR Application Toolbox: Software to facilitate chemical grouping and data gap filling [3].

- EPA's Analog Identification Methodology (AIM) Tool: Helps identify potential structural analogs [6].

- Chemical Hazard Data Trust (e.g., ChemFORWARD): A repository of curated hazard data for thousands of chemicals [7].

Protocol 2: Systematic Data Gap Identification for a Single Chemical

- Objective: To create a comprehensive profile of data availability and sparsity for a target chemical.

- Workflow:

- Materials:

Data Presentation: Methodologies for Filling Data Gaps

The table below summarizes the primary methodologies for addressing data gaps in chemical hazard assessment, as referenced in the search results.

| Methodology | Core Principle | Example Tools/Citations | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read-Across / Chemical Categories [3] [6] | Uses experimental data from chemically similar compounds (analogues) to predict the property of the target chemical. | OECD QSAR Toolbox, EPA's AIM Tool [3] [6] | Filling a specific toxicity endpoint gap (e.g., skin irritation) for a data-poor chemical. |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) [3] [6] | Uses computer models to correlate a chemical's molecular structure or properties with its biological activity. | EPA ECOSAR, EPA OncoLogic [6] | Generating a quantitative toxicity estimate (e.g., LC50) for priority-setting when no analogues exist. |

| Targeted Testing / Sampling [1] | Designs and conducts new experimental studies or environmental sampling to collect missing empirical data. | Data Quality Objectives (DQO) Process [1] | Providing definitive data when predictive methods are unsuitable or regulatory requirements demand empirical proof. |

| Weight-of-Evidence (WoE) [6] | Integrates multiple lines of evidence (e.g., read-across, QSAR, in vitro data) to support a hazard conclusion. | N/A (A conceptual approach) | Building a robust case for a hazard classification when data from any single source is insufficient. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key tools and resources essential for identifying and filling data gaps in chemical hazard assessment.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Data Gaps |

|---|---|---|

| OECD QSAR Toolbox [3] | Software to group chemicals into categories, identify analogues, and fill data gaps via read-across. | The primary tool for implementing the read-across methodology in a standardized way. |

| EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [2] [6] | A hub providing access to multiple data sources (ToxCast, ToxRefDB) and computational tools. | Used to gather existing experimental data and identify data gaps via tools like GenRA. |

| Chemical Hazard Assessment (CHA) Frameworks (e.g., GreenScreen) [4] | A standardized method for assessing and benchmarking chemicals against 24+ hazard endpoints. | Provides a structured checklist of endpoints required for a full assessment, making gap identification systematic. |

| Chemical Hazard Data Trust (e.g., ChemFORWARD) [7] | A curated repository of chemical hazard data from dozens of authoritative sources. | Simplifies data gathering from multiple sources, reducing the time and cost of identifying and filling gaps. |

| ECOSAR [6] | A program that uses QSARs to predict the aquatic toxicity of untested chemicals. | Specifically used to fill data gaps for ecological hazard endpoints like acute and chronic toxicity to fish and invertebrates. |

| Nocardicyclin B | Nocardicyclin B, MF:C32H37NO12, MW:627.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Andrastin D | Andrastin D, MF:C26H36O5, MW:428.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the most critical data gaps to look for when reviewing chemical supplier documentation?

The most critical data gaps often involve environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics, full chemical composition disclosure, and toxicokinetic data. Many regulatory exposure assessments are flawed due to systemic issues like the use of 'confidential business information' which reduces available data, outdated assessment models, and inadequate assumptions about human behavior and co-exposures [8]. Specifically, you should verify:

- Completeness of ESG Data: 66% of procurement leaders report that ESG criteria heavily influence strategic sourcing decisions [9]. Ensure data for carbon emissions, waste reduction, and water conservation is present and verified through third-party audits [9].

- Chemical Exposure and Safety Data: Supplier data must go beyond basic safety data sheets. Look for comprehensive toxicological profiles and physiologically based toxicokinetic (PBTK) models, as insufficient models contribute to significant underestimates of exposure in risk assessments [8].

- Supply Chain Transparency: Documentation should provide multi-tier visibility. A key industry trend is the use of blockchain for immutable records and supplier verification to prevent counterfeit materials from entering the supply chain [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Inconsistent Supplier Benchmarks

- Problem: Difficulty comparing supplier performance data due to inconsistent reporting formats or missing key performance indicators (KPIs).

- Solution: Implement a standardized supplier scoring matrix. This automates evaluation across multiple performance dimensions and ensures consistency [9].

- Step 1: Define standardized KPIs. Categorize them into financial, operational, environmental, and social dimensions [9].

- Step 2: Collect data against these KPIs. Utilize cloud-based procurement platforms to seamlessly integrate information from various sources [9].

- Step 3: Apply a weighted scoring system. The following table provides a sample framework based on industry trends [9]:

Table: Standardized Supplier Scoring Matrix

| Evaluation Category | Evaluation Weight | Key Metrics | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 45% | Carbon emissions, waste reduction, water conservation | Third-party audits, site inspections [9] |

| Social | 35% | Labor practices, safety records, diversity and inclusion | Site inspections, compliance records [9] |

| Governance | 20% | Ethics compliance, transparency, financial stability | Financial analysis, audit trails [9] |

FAQ 2: How can we efficiently identify and qualify alternative suppliers to mitigate risk?

A multi-pronged approach leveraging technology is most effective. The chemical industry is prioritizing regional supply chain resilience and using AI-driven tools for rapid supplier discovery [9].

- Utilize Digital Marketplaces and AI: Digital platforms transform supplier discovery through automated bidding systems and competitive processes. Machine learning algorithms can analyze thousands of potential suppliers simultaneously, assessing financial stability and operational capabilities [9].

- Conduct a Comprehensive Risk Evaluation: Implement a continuous risk assessment framework. This involves multi-tier supplier mapping to identify hidden dependencies and scenario planning for various disruption possibilities [9].

Table: Supplier Risk Assessment Framework

| Risk Category | Assessment Frequency | Monitoring Tools | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | Monthly | Credit ratings, financial reports | Diversified payment terms, financial guarantees [9] |

| Operational | Weekly | Performance metrics, audit results | Pre-qualified alternative suppliers, safety inventory [9] |

| Geopolitical | Continuous | News monitoring, intelligence feeds | Geographic diversification of supplier base [9] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Data Silos in Supplier Qualification

- Problem: Supplier data is trapped in isolated systems (e.g., ERP, emails, individual spreadsheets), preventing a unified view.

- Solution: Deploy a centralized, cloud-based procurement platform with advanced analytics [9].

- Step 1: Audit all existing data sources, including ERP systems, invoices, and contracts [9].

- Step 2: Integrate these sources into a single cloud-based platform that offers global accessibility and automatic scaling [9].

- Step 3: Use the platform's built-in spend analytics and business intelligence tools to identify cost reduction opportunities and performance trends across the unified data set [9].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Systematic Supplier Identification and Data Gap Analysis

1. Objective To establish a standardized methodology for identifying, evaluating, and benchmarking chemical suppliers while systematically identifying and documenting data gaps in their provided information.

2. Pre-Assessment Planning

- Define Material Specifications: Clearly outline the required chemical properties, purity grades, and compliance certifications.

- Assemble a Cross-Functional Team: Include members from R&D, procurement, quality assurance, and environmental health & safety (EHS).

- Establish Data Requirements: Create a checklist of all required data points based on the scoring matrix and risk assessment framework above.

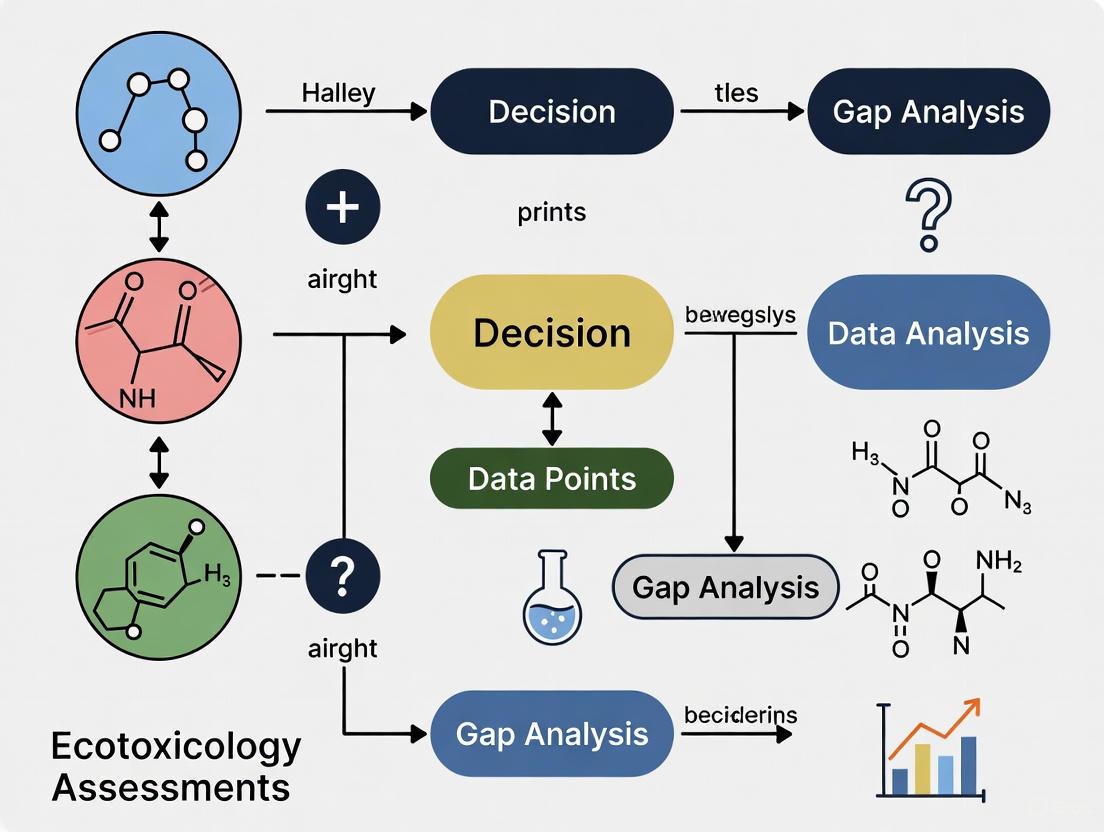

3. Experimental Workflow The following diagram outlines the core workflow for systematic supplier identification.

4. Data Gap Analysis Methodology

- Step 1 - Document Collection: Issue a formal Request for Information (RFI) to potential suppliers, demanding data against your predefined checklist.

- Step 2 - Triage and Categorization: Log all received documents. Categorize missing data points as either "Critical" (e.g., safety data, ESG audit reports), "Important" (e.g., financial stability details), or "Optional" (e.g., specific process details).

- Step 3 - Gap Documentation: Record all missing or insufficient data in a central register. Note the date of request and the supplier's reason for non-provision (e.g., Confidential Business Information).

- Step 4 - Impact Assessment: Evaluate how each data gap affects the overall risk score and the ability to conduct a complete chemical assessment.

Protocol: Exposure Assessment Validation for Supplier Materials

1. Objective To validate supplier-provided exposure and safety data against independent models and biomonitoring, addressing common systemic underestimations in chemical assessments [8].

2. Methodology

- Toxicokinetic Modeling Review: Compare the supplier's PBTK models with independent, peer-reviewed models. Pay specific attention to assumptions about metabolic pathways and tissue partitioning, as these are common sources of error [8].

- Aggregate Exposure Assessment: Do not rely on single-pathway exposure estimates. Model all potential exposure routes (ingestion, inhalation, dermal) from all sources to account for aggregate exposures that regulatory assessments often miss [8].

- Biomonitoring Comparison: Where possible, compare modeled exposure estimates with biomonitoring data (measurements of chemicals in blood, urine) from occupational or community settings. A significant discrepancy suggests the model is flawed [8].

The logical relationship for validating data is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Digital and Analytical Tools for Supplier Data Management

| Tool / Solution Name | Function | Application in Systematic Identification |

|---|---|---|

| AI-Powered Procurement Platforms | Automated supplier discovery and evaluation using machine learning algorithms [9]. | Rapidly scans thousands of suppliers, performs initial financial and operational risk scoring, and identifies potential data gaps in public profiles. |

| Spend Analytics Software | Analyzes procurement data across ERP systems and contracts to identify trends and opportunities [9]. | Provides a data-driven basis for benchmarking supplier costs and performance, highlighting discrepancies that may indicate data or compliance issues. |

| Blockchain Supply Chain Platforms | Creates immutable records of transactions and product provenance [9]. | Verifies the authenticity of materials and provides an auditable trail for regulatory compliance, directly addressing data gaps related to source and handling. |

| Cloud-Based Collaboration Systems | Enables global team access to supplier data and documents in real-time [9]. | Centralizes the supplier data collection and gap analysis process, ensuring all team members work from a single source of truth. |

| ESG Data Verification Services | Third-party audits of environmental and social metrics [9]. | Independently verifies critical supplier claims on carbon footprint, labor practices, and safety records, filling a major data gap in self-reported information. |

| Roselipin 1B | Roselipin 1B, MF:C40H72O14, MW:777.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mumefural | Mumefural, CAS:222973-44-6, MF:C12H12O9, MW:300.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common types of data gaps in pharmaceutical research and development? Data gaps in pharma R&D frequently occur in several key areas. A major gap is the lack of skilled personnel who can bridge domain expertise (e.g., biology, chemistry) with technical AI and data science skills; nearly half of industry professionals report this as the top hindrance to digital transformation [10]. In chemical risk assessment, gaps often involve incomplete toxicological profiles for new chemical alternatives (e.g., bisphenol A substitutes), specifically missing data on toxicokinetics, endocrine disruption, and developmental neurotoxicity [11]. Furthermore, insufficient data to characterize exposure is common, where the spatial and temporal extent of sampling does not adequately represent potential site exposures [1].

FAQ 2: How can I identify if my project has a critical data gap? A data gap is critical if incomplete information prevents you from reaching a definitive public health or safety conclusion [1]. Key indicators include:

- Data does not include all potentially affected media (e.g., un-sampled soil or water sources in an exposure pathway) [1].

- Data does not include analysis for all potential contaminants of concern [1].

- The amount of data is insufficient to characterize exposure or risk confidently [1].

- High failure rates in R&D (up to 90% for new drug candidates) often point to underlying gaps in predictive modeling and early-stage testing capabilities [12].

FAQ 3: What methodologies can be used to fill quantitative data gaps in chemical risk assessment? To bridge quantitative gaps, especially for data-poor chemicals, you can employ Non-Targeted Analysis (NTA) methods. NTA can screen for known and previously unknown compounds. When coupled with quantitative efforts and predictive models, NTA data can support modern risk-based decisions [13]. Other methodologies include:

- Modeling studies that predict contamination levels [1].

- Exposure Investigations (EI) to collect new biological or environmental data [1].

- Designing targeted sampling programs with clear Data Quality Objectives (DQOs) to ensure collected data is representative and fit-for-purpose [1].

FAQ 4: What is the "AI skills gap" and how does it impact pharmaceutical innovation? The AI skills gap is the shortfall between the AI-related technical abilities pharma companies need and the capabilities of their existing workforce [10]. This is not just a lack of data scientists, but a mismatch in interdisciplinary skills. It manifests as a technical skills deficit (e.g., in machine learning, NLP), a domain knowledge shortfall (where data scientists lack pharma expertise), and a lack of "AI translators" who can bridge these domains [10]. This gap stalls critical projects, raises costs, and can ultimately impact drug quality and patient safety [10]. About 70% of pharma hiring managers have difficulty finding candidates with both deep pharmaceutical knowledge and AI skills [10].

FAQ 5: What are the key components of a sampling plan designed to fill a data gap? A robust sampling plan to fill data gaps should document the following items [1]:

- Clear technical goals and Data Quality Objectives (DQOs), including precision, accuracy, and representativeness.

- Environmental media to be sampled and the analytes to be measured.

- Sampling and analytical methods to be used.

- Proposed sampling locations and a schedule (frequency and duration).

- Quality Assurance/Quality Control (QA/QC) measures, such as duplicate samples, blanks, audit samples, and sample handling procedures.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Data Gaps in Environmental Exposure Assessment

This guide helps researchers systematically identify and address data gaps in scenarios like site contamination assessments.

1. Define the Problem & Pathway

- Problem: Start by creating a conceptual model of the complete exposure pathway. This includes a contaminant source, an environmental transport mechanism (e.g., leaching, air dispersion), a point of potential contact with humans or ecosystems, and a receptor population [1].

- Check: Is the entire pathway fully understood and characterized with data?

2. Identify the Gap The data gap will typically fall into one of these categories. Use the table below to diagnose the issue.

| Data Gap Category | Symptoms | Common Sources in Pharma/Chemical Contexts |

|---|---|---|

| Media Gaps [1] | A potentially affected environmental medium (e.g., indoor air, groundwater, surface soil) was never sampled. | Unplanned chemical releases; non-professional use of plant protection products (PPPs) in residential settings [14]. |

| Analyte Gaps [1] | Sampling was conducted, but not analyzed for the specific contaminant of concern (CoC). | Use of novel chemical alternatives (e.g., BPS, BPF) with unknown or unmonitored toxicological profiles [11]. |

| Spatial/Temporal Gaps [1] | Data does not cover the full geographical area or time period of potential exposure. | Limited monitoring programs; insufficient data for seasonal fluctuations or long-term trend analysis. |

| Quantitative Gaps [13] | Chemicals are identified, but their concentrations cannot be accurately quantified for risk characterization. | Use of Non-Targeted Analysis (NTA) methods that are primarily qualitative. |

3. Select a Remediation Methodology Choose a method based on the gap type identified in Step 2.

- For Media, Analyte, or Spatial/Temporal Gaps: Design and implement a new, targeted sampling program. Follow the protocol in the "Experimental Protocol" section below [1].

- For Quantitative Gaps:

4. Verify and Validate

- After collecting new data, verify that it meets the pre-defined Data Quality Objectives (DQOs) [1].

- Integrate the new data into your risk assessment model to ensure it allows for a conclusive public health judgment [1].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting the AI and Skills Gap in Pharma R&D

This guide addresses the human capital and competency gaps hindering digital transformation.

1. Diagnose the Specific Skills Shortfall Determine where your team's capabilities are lacking. The gap is often multidimensional [10].

| Skill Deficit Type | Symptoms | Impact on Projects |

|---|---|---|

| Technical AI Skills | Inability to build, deploy, or maintain machine learning models (e.g., for target identification or clinical trial optimization). | Stalled digital projects; reliance on external vendors for core capabilities; inability to leverage R&D data fully [10]. |

| Domain Bridge Skills | Data scientists and AI experts cannot effectively communicate with biologists and chemists, and vice versa. | Misapplication of AI tools; models that are technically sound but biologically irrelevant; slow project iteration [10]. |

| Data Literacy | Domain scientists struggle to interpret the output of advanced analytics or AI systems. | Mistrust of AI-driven insights; failure to adopt new data-driven workflows; misinterpretation of results [10]. |

2. Implement a Bridging Strategy Select and implement strategies to close the identified skills gap.

- For Widespread Data Literacy Gaps: Launch large-scale upskilling programs. For example, companies like Johnson & Johnson have trained tens of thousands of employees in AI literacy to embed skills "across the board" [10].

- For a Lack of "AI Translators":

- Reskill Existing Talent: Prioritize reskilling existing domain experts (e.g., biologists, chemists) in data science fundamentals. This is cost-effective and improves retention [10].

- Create New Roles: Formally establish roles like "AI Translator" or "Digital Biologist" to act as bridges between technical and domain teams [10].

- For Acute Technical Skill Gaps: Partner with specialized tech companies, startups, or academic consortia to access external expertise quickly [10].

3. Foster a Continuous Learning Culture

- The AI field evolves rapidly. Encourage ongoing learning through certifications, workshops, and access to online training platforms [10].

- Integrate AI tools into daily workflows to promote hands-on learning and familiarity [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing a Sampling Plan to Fill an Environmental Data Gap

This protocol, based on EPA and ATSDR guidance, provides a step-by-step method for collecting new environmental data to fill a identified gap [1].

1. State the Principal Study Question

- Clearly articulate the public health question the sampling is designed to answer. (e.g., "What is the concentration of Bisphenol S (BPS) in residential tap water downstream from the manufacturing facility?") [1].

2. Define Data Quality Objectives (DQOs)

- Go through the seven-step DQO process to define the quality of data needed [1]:

- State the problem.

- Identify the decision.

- Identify inputs to the decision.

- Define the study boundaries.

- Develop a decision rule.

- Specify limits on decision errors.

- Optimize the design for obtaining data.

3. Develop the Sampling Plan Document The plan must include [1]:

- Environmental Media & Analytes: Specify the media (e.g., soil, water, air) and the exact chemical analytes to be measured.

- Sampling & Analytical Methods: Specify the standardized methods (e.g., "EPA Method 551.1").

- Sampling Locations: Define a specific, justified sampling grid or set of points.

- Sampling Schedule: Set the frequency, duration, and timing of sampling.

- QA/QC Measures: Detail the use of field blanks, trip blanks, duplicate samples, and audit samples to ensure data quality.

Workflow Diagram: Environmental Data Gap Resolution

Protocol 2: Implementing a Reskilling Program to Bridge the AI Skills Gap

This protocol outlines a methodology for upskilling existing pharmaceutical R&D staff in AI and data science competencies [10].

1. Skills Assessment and Program Design

- Audit Current Skills: Conduct a survey to assess the current levels of data literacy, programming skills (e.g., Python, R), and understanding of machine learning concepts among R&D staff.

- Define Target Competencies: Identify the specific skills needed for target roles (e.g., "Digital Biologist"). These typically include foundational data science, statistics, machine learning, and the application of AI to specific domains like genomics or clinical data analysis [10].

- Choose a Training Modality: Decide on in-person workshops, online courses, or a hybrid model. Partnering with a business school or technical institute (e.g., Bayer's partnership with IMD) can be effective [10].

2. Program Implementation and Support

- Launch Pilot Cohort: Begin with a small, motivated group to refine the curriculum.

- Integrate with Work: Structure training around real-world, company-specific problems to ensure immediate relevance and application.

- Provide Mentorship: Pair trainees with senior data scientists or "AI translators" for guidance.

3. Measurement and Evaluation

- Track Completion Rates: Monitor participation and completion rates (e.g., Bayer's program achieved an 83% completion rate) [10].

- Measure Impact: Evaluate the program's success through metrics like project efficiency gains (e.g., reskilled teams saw 15% efficiency gains), employee retention (e.g., 25% boost in retention), and the number of new AI-driven initiatives launched by trainees [10].

Workflow Diagram: AI Skills Gap Bridging Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, software, and methodologies crucial for conducting experiments in chemical risk assessment and filling data gaps.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Context in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Targeted Analysis (NTA) [13] | A high-resolution analytical method (often using LC-HRMS) to screen for and identify both known and unknown chemicals in a sample without a pre-defined target list. | Identifying emerging contaminants or data-poor compounds in environmental or biological samples to support hazard identification. |

| Quantitative NTA (qNTA) Standards [13] | Internal standards and calibration curves used to convert the semi-quantitative signals from NTA into concentration estimates with defined uncertainty. | Bridging the quantitative gap for risk assessment of chemicals identified via NTA screening. |

| Data Quality Objectives (DQOs) [1] | A qualitative and quantitative statement from the systematic planning process that clarifies study objectives, defines appropriate data types, and specifies tolerable levels of potential decision errors. | Planning a sampling program to ensure the data collected is of sufficient quality and quantity to support a definitive public health conclusion. |

| AI/ML Platforms (e.g., Graph Neural Networks) [15] | A class of artificial intelligence used to generate molecular structures, predict bio-activity, and accelerate the drug discovery process. | In-silico molecule generation and prediction of reactivity during early-stage drug discovery. |

| Digital Twins [12] | A virtual replica of a physical entity or process (e.g., a virtual patient). Allows for in-silico testing of drug candidates and simulation of clinical trials. | Speeding up clinical development by simulating a drug's effect on a virtual population and optimizing trial design. |

| Real-World Evidence (RWE) Platforms [12] | Systems that gather, standardize, and analyze data derived from real-world settings (e.g., electronic health records, patient registries) to generate evidence about drug usage and outcomes. | Post-market safety monitoring; supporting regulatory submissions for new drug indications. |

| Pentenocin A | Pentenocin A, MF:C7H10O5, MW:174.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Arisugacin B | Arisugacin B, MF:C27H30O7, MW:466.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Modern Toolbox: Applying NAMs and Computational Strategies to Fill Data Gaps

Leveraging Chemical Categories and Read-Across for Efficient Data Filling

Core Concepts: Understanding Read-Across

What is the fundamental principle behind read-across?

Read-across is a technique used to fill data gaps for a poorly studied "target" chemical by using existing experimental data from one or more well-studied "source" chemicals that are considered "similar" in some way [16] [17] [18]. This similarity is typically based on structural, toxicokinetic, or toxicodynamic properties [17] [18].

When should I consider using a read-across approach?

Read-across is particularly valuable when a target chemical lacks sufficient experimental data for hazard identification and dose-response analysis, which is common for many chemicals in commerce [18]. It is used in regulatory programs under REACH in the European Union and the U.S. EPA's Superfund and TSCA programs [18].

What is the difference between the "Analogue" and "Category" approaches?

- Analogue Approach: Uses a single source chemical as the analogue for the target chemical [17].

- Category Approach: Uses a group of chemicals as the source. The properties of the group as a whole are used to predict the hazard of the target chemical. The data across the category should be adequate, and a regular trend in properties may be observed [17].

Implementation Guide: Performing a Read-Across Assessment

How do I systematically identify potential source analogues?

You can use algorithmic tools to identify candidate source analogues objectively. The U.S. EPA's Generalized Read-Across (GenRA) tool, available via the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, allows you to search for candidates based on [16]:

- Structural fingerprints: Using molecular frameworks and common functional groups.

- Bioactivity fingerprints: Using in vitro bioactivity data from high-throughput screening (HTS) assays.

- Hybrid fingerprints: A combination of structural and bioactivity similarity.

Other sources include the OECD QSAR Toolbox, which can determine a quantitative similarity index based on structural fragments [17].

What are the key criteria for justifying that chemicals are sufficiently similar?

A robust read-across justification should be based on a Weight of Evidence (WoE) approach and consider the following aspects of similarity [17] [18]:

- Structural Similarity: The presence of common functional groups, molecular frameworks, and constituents [17].

- Physico-chemical Property Similarity: Properties like log Kow, water solubility, and vapor pressure that affect bioavailability and toxicity [17].

- Metabolic and Toxicokinetic Similarity: Similarity in potential metabolic products and biodegradation pathways [17] [18].

- Mechanistic Similarity: Sharing a common Mechanism of Action (MOA) or Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) [17] [18].

What are the common pitfalls in building a read-across justification, and how can I avoid them?

| Pitfall | Description | Troubleshooting Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-reliance on Structure | Assuming structural similarity alone guarantees similar toxicity. | Integrate biological data (e.g., HTS bioactivity) to support the hypothesis of similar MOA [16] [18]. |

| Ignoring Metabolic Activation | Not considering if a chemical requires metabolic activation to become toxic. | Use tools like the OECD QSAR Toolbox to identify potential metabolic transformations and account for them in your rationale [17]. |

| Inadequate Documentation | Failing to clearly document the rationale, data, and uncertainties. | Maintain thorough documentation for every step, from analogue identification to final justification, to provide clear evidence for your assessment [17]. |

| Data Sparsity in Sources | Using source analogues that themselves have significant data gaps. | Use tools like the GenRA Data Gap Matrix to visualize data availability and sparsity across your candidate analogues before making predictions [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Read-Across Workflow

The following workflow, adapted from international guidance and the U.S. EPA's framework, provides a structured methodology for a read-across assessment [17] [18].

Protocol Steps:

- Problem Formulation: Define the goal. Identify the target chemical and the specific data gap (e.g., missing inhalation toxicity value for a particular endpoint) [18].

- Identify Potential Source Analogues: Use computational tools (e.g., U.S. EPA's GenRA, OECD QSAR Toolbox) to search for chemicals with structural or bioactivity similarity to your target [16] [17].

- Gather All Available Data: For the target and candidate source chemicals, collect all relevant published and unpublished data. This includes [17]:

- Chemical structures, identifiers, and purity profiles.

- Physico-chemical properties (e.g., log Kow, water solubility).

- In vivo toxicity data and in vitro bioactivity data.

- Information on metabolism, degradation, and Mechanism of Action (MOA).

- Develop Rationale & Justify Similarity: This is the core of the assessment. Systematically evaluate and document the similarities (and differences) between the target and source chemicals across multiple criteria: structural, physico-chemical, metabolic, and mechanistic [17] [18].

- Perform Data Gap Filling: Once similarity is established, the experimental data from the source chemical(s) can be used to predict the endpoint for the target chemical. Tools like GenRA can make similarity-weighted activity predictions for both binary (hazard/no hazard) and potency-based outcomes [16].

- Document and Report: Maintain clear and transparent documentation of the entire process, including all data, the WoE justification, and a discussion of any uncertainties [17].

Data Interpretation & Visualization

How can I effectively visualize and compare data availability before making predictions?

The U.S. EPA's GenRA tool provides specific panels for this purpose. The Data Gap Matrix visualizes the presence (black boxes) and absence (gray boxes) of data for the target chemical and its source analogues across different study type-toxicity effect combinations [2]. This helps you understand data sparsity before proceeding.

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Key Features / Data |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. EPA GenRA [16] | An algorithmic, web-based tool for objective read-across predictions. | Predicts in vivo toxicity and in vitro bioactivity; identifies analogues based on chemical/bioactivity fingerprints; provides data gap matrices and similarity-weighted predictions. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox [17] | A software application to group chemicals into categories and fill data gaps. | Provides profiling tools for mechanistic and toxicological effects; databases for identifying structural analogues and metabolic pathways. |

| U.S. EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [16] [18] | A centralized portal for chemistry, toxicity, and exposure data for thousands of chemicals. | Links to GenRA; provides access to a wealth of physico-chemical property, in vivo toxicity (ToxRefDB), and in vitro bioactivity (ToxCast) data. |

| Systematic Review Methods [18] | A structured approach to gathering and evaluating all available scientific evidence. | Ensures a transparent, reproducible, and comprehensive collection of data for the target and source chemicals, reducing bias. |

Hmm, the user is asking for a technical support center with troubleshooting guides and FAQs about New Approach Methodologies, specifically focused on in vitro and in silico models. They want this framed within a chemical assessments research context for an audience of researchers and scientists.

I need to structure this as a practical resource that directly helps researchers solve problems they encounter in their NAM experiments. The response should include FAQs, troubleshooting tables, detailed protocols, and visual workflows.

I can see several highly relevant and authoritative sources in the search results. [19] provides excellent foundational information about what NAMs are and their core components, which will support the introductory FAQ section. [20] offers crucial technical details about PBPK modeling and virtual populations, perfect for the in silico modeling FAQ and experimental protocols. [21] gives practical insights into specific tools like Maestro MEA systems and their applications in cardiotoxicity and neurotoxicity testing.

[22] provides comprehensive coverage of NAMs in risk assessment context, which aligns well with the user's requirement about chemical assessments research. [23] shows a specific case study using 4-NP that demonstrates real-world application of NAMs for chemical safety decisions. [24] covers current workshop discussions from 2025, adding timeliness to the response.

I will reference [25] cautiously for the in-silico trials concepts since it's from a consulting firm rather than a research source, though the technical content appears sound. [26] and [27] are less directly relevant to the technical troubleshooting focus the user needs. [28] is commercial content that I will use sparingly, primarily for the tools table context.

For the DOT diagrams, I plan to create clear workflows that show the logical relationships between different NAM components and troubleshooting steps, using the restricted color palette and ensuring proper contrast. The tables will organize quantitative data about common issues and research tools, making the information immediately useful for researchers. The experimental protocols need to be detailed enough to be practically useful while staying within what the search results support.

The response will flow from general FAQs to specific troubleshooting, then to detailed protocols and available tools, mirroring how researchers would actually seek help when problems arise in their work.

FAQs: Understanding NAMs and Their Applications

What are New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)?

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) are innovative, non-animal testing methods used in biomedical research and chemical safety testing [21]. They encompass a range of scientific tools, including in vitro models (like 2D & 3D cell cultures, organoids, and organs-on-chips), in silico models (computational approaches like AI and PBPK modeling), and in chemico methods (such as protein assays for irritancy) [19]. The key aspect of all NAMs is that they are based on non-animal technologies to facilitate the identification of hazards and/or risks of chemicals [24].

Why is there a push to adopt NAMs now?

The adoption of NAMs is accelerating due to a convergence of regulatory shifts, ethical imperatives, and scientific advancements. In 2025, the U.S. FDA and NIH issued new guidance reinforcing the "3Rs" principle (Replace, Reduce, and Refine animal use) and aiming to make animal studies the exception rather than the rule in preclinical safety testing [19] [21]. Scientifically, NAMs offer more human-relevant data, potentially overcoming the limitations of animal models, where over 90% of drugs that pass preclinical animal testing still fail in human clinical trials [21].

What are the most common applications of in silico models in chemical risk assessment?

In silico models are versatile tools used throughout the chemical risk assessment process [22]. Key applications include:

- Prioritization and Screening: Using Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models and molecular docking to predict toxicity and prioritize chemicals for further testing [22].

- Point of Departure (PoD) Estimation: Applying benchmark dose (BMD) modeling to in vitro or toxicogenomic data to derive a dose at which a biological response is first observed, which is crucial for setting safety values [22].

- Risk Translation: Utilizing Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models to predict the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of chemicals in humans, translating in vitro findings to in vivo exposures [20] [22].

- Supporting Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs): Computational methods help integrate and interpret large datasets to enrich AOPs, which describe sequences of biological events leading to an adverse health effect [22].

Will NAMs completely replace animal testing in the near future?

Experts suggest that a complete replacement is not immediate but is a long-term goal [19]. The transition is best approached incrementally. A practical way is to start small, using NAMs alongside animal studies, and then build evidence of their reliability for specific endpoints [19]. Regulators are open to this approach, but early engagement with agencies like the FDA is key to ensuring alignment with regulatory expectations [21].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

This section addresses specific technical issues you might encounter when working with NAMs, offering potential causes and solutions.

In Vitro Model Challenges

Table: Troubleshooting In Vitro NAMs

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in 3D organoid assays | Inconsistent organoid size and differentiation; edge effects in culture plates; high passage number of cells [21]. | Standardize production protocols (e.g., Axion iPSC Model Standards - AIMS); use imaging and AI-powered analysis (e.g., Omni imagers) to quantify and control for size/shape; limit cell passaging [21]. |

| Poor predictivity for neural or cardiac toxicity | Using non-human or non-physiologically relevant cell sources; relying on single, static endpoint measurements [21]. | Adopt human iPSC-derived neurons/cardiomyocytes; use functional readouts like label-free, real-time electrical activity monitoring with Maestro Multielectrode Array (MEA) systems [21]. |

| Low barrier integrity in microphysiological systems | Inappropriate cell seeding density; membrane damage during handling; sub-optimal culture conditions for the specific cell type [21]. | Use impedance-based analyzers (e.g., Maestro Z) to track barrier integrity (TEER) noninvasively over time; optimize seeding density with accurate cell counters [21]. |

In Silico Model Challenges

Table: Troubleshooting In Silico NAMs

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| PBPK model fails to predict human pharmacokinetics | Model over-reliance on animal data; virtual population does not reflect the target human population's physiology (e.g., age, disease state) [20]. | Incorporate human-specific physiological and RWD; use virtual populations tailored to specific clinical settings (e.g., geriatrics, renal impairment) [20]. Validate with available clinical data. |

| Difficulty deriving a Point of Departure (PoD) from in vitro data | Lack of a standardized framework for data reporting and analysis; high uncertainty in extrapolations [22]. | Follow established OMICS reporting frameworks (e.g., OECD OORF) for reproducibility; combine in vitro data with BMD modeling and PBPK models for quantitative in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (QIVIVE) [22]. |

| Low regulatory confidence in QSAR or read-across predictions | Insufficient justification for the chosen analogue or model; lack of a robust "weight of evidence" approach [22]. | Use the OECD toolbox to combine multiple NAMs approaches (in vitro, OMICS, PBK, QSAR) to build a compelling weight of evidence [22]. Adhere to guidance from ECHA and EFSA on read-across [22]. |

Troubleshooting high variability in organoid assays.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key NAM experiments cited in recent literature.

Protocol: Neural Seizure Risk Assessment using Microelectrode Array (MEA)

Background: Neurotoxicity is a leading cause of drug failure, and drug-induced seizures result from excessive, synchronous firing of cortical neurons [21]. This protocol uses human iPSC-derived neurons to predict seizure risk functionally.

Workflow:

- Cell Culture: Plate human iPSC-derived cortical neurons on a Maestro MEA plate coated with an appropriate substrate (e.g., poly-D-lysine, laminin). Maintain cultures in neuronal maintenance media, allowing neural networks to mature and form synchronous connections over 2-4 weeks [21].

- Baseline Recording: Place the MEA plate in the Maestro MEA system. Record the spontaneous electrical activity (mean firing rate, burst properties, network synchrony) from the neural network for at least 10 minutes to establish a stable baseline [21].

- Compound Application: Apply the test compound at multiple concentrations (e.g., 3-5 concentrations covering a therapeutic and supra-therapeutic range) to the culture medium. Include both negative (vehicle) and positive (known seizurogenic compound) controls in each experiment.

- Post-Compound Recording: Immediately after compound application, record electrical activity for a minimum of 30-60 minutes to capture acute changes.

- Data Analysis: Use the platform's software to analyze changes in key parameters. A significant, concentration-dependent increase in mean firing rate and network bursting is indicative of pro-convulsant or seizurogenic risk.

- AI/ML Enhancement (Optional): For improved prediction, export the raw spike or burst data and apply artificial intelligence-based machine-learning algorithms (e.g., like those discussed by NeuroProof) to classify the seizure risk from the complex activity patterns [21].

Workflow for MEA-based seizure risk assessment.

Protocol: Quantitative In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation (QIVIVE) for Systemic Toxicity

Background: This methodology is critical for using in vitro NAMs data in quantitative chemical risk assessment. It integrates in vitro bioactivity data with PBPK modeling to estimate a safe human exposure level [23] [22].

Workflow:

- In Vitro Bioactivity Testing: Expose relevant human cell lines (e.g., HepaRG for liver, primary hepatocytes) to a range of concentrations of the test chemical (e.g., 4-nonylphenol). Generate high-throughput dose-response data for key toxicity endpoints (e.g., cell viability, mitochondrial toxicity, oxidative stress) [23] [22].

- Point of Departure (PoD) Derivation: Fit the concentration-response data using benchmark dose (BMD) modeling software. The concentration corresponding to a benchmark response (BMR, e.g., a 10% change in effect) is defined as the in vitro PoD [22].

- Reverse Dosimetry using PBPK: Develop or apply an existing PBPK model for the chemical. The model should be parameterized with human physiological data (organ volumes, blood flows, enzyme expression). Use "reverse dosimetry" to convert the in vitro PoD (concentration in the well) into an equivalent human oral dose. This is done by running the PBPK model iteratively to find the daily external dose that would result in a steady-state plasma or tissue concentration equal to the in vitro PoD [20] [22].

- Incorporation of Pharmacokinetics: Adjust the calculated dose using in vitro-to-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) of clearance to account for differences in protein binding and metabolic clearance between the in vitro system and humans [20].

- Application of Uncertainty Factors: Apply appropriate assessment factors (e.g., for inter-human variability, duration of exposure) to the extrapolated dose to derive a human-relevant guidance value, such as a Tolerable Daily Intake (TDI) [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Tools and Reagents for NAMs Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Human iPSCs (Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells) | Source for generating patient-specific and human-relevant cell types for in vitro models. | Differentiating into cardiomyocytes for cardiotoxicity testing on MEA platforms [21]. |

| Maestro MEA System | Label-free, noninvasive measurement of real-time electrical activity from neural and cardiac cells in 2D or 3D cultures. | Functional assessment of drug-induced changes in cardiac action potentials (CiPA assay) or neural network synchrony (seizure prediction) [21]. |

| Organ-on-a-Chip | Microfluidic devices that mimic the structure and function of human organs, allowing for more complex, dynamic cultures. | Creating a liver-on-a-chip to study metabolism-mediated toxicity or a blood-brain-barrier model to assess neurotoxicity [19] [21]. |

| PBPK Modeling Software (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) | In silico platforms that simulate the ADME of compounds in virtual human populations. | Conducting QIVIVE to translate in vitro toxicity data into a safe human equivalent dose [20] [22]. |

| OSDPredict / Quadrant 2 | AI/ML-powered digital toolboxes that predict formulation behavior, solubility, and bioavailability. | Saving precious API in early development by predicting solubility and FIH dosing, de-risking formulation decisions [28]. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Software that supports chemical hazard assessment by filling data gaps via read-across and grouping of chemicals. | Identifying structurally similar chemicals with existing data to predict the hazard profile of a data-poor chemical [22]. |

| Xinjiachalcone A | Xinjiachalcone A, MF:C21H22O4, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ligupurpuroside A | ligupurpuroside A, CAS:147396-01-8, MF:C35H46O19, MW:770.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementing QSAR and the OECD QSAR Toolbox in Regulatory Contexts

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the definition of the primary group so slow in the Toolbox? The process of defining the primary group can be computationally intensive, as it involves profiling the target chemical, identifying structurally and mechanistically similar analogues from extensive databases, and applying complex grouping logic. The speed can vary depending on the complexity of the chemical structure and the profilers used [29].

Q2: My antivirus software detects a potential threat in the Toolbox. What should I do? This is a known false positive. The QSAR Toolbox is safe software. The development team works to resolve these issues with antivirus providers. You can configure your antivirus to exclude the Toolbox installation directory, or download the latest version where such issues are typically resolved [29].

Q3: How do I export data from the ECHA REACH database using the Toolbox? The Toolbox provides functionalities for exporting data. You can use the Data Matrix wizard to build and export data matrices, which saves the data you have collected for your chemicals and their analogues into a structured format, such as Excel, for further analysis or reporting [30].

Q4: What does the 'ignore stereo/account stereo' option mean? This option allows you to control whether the stereochemistry of a molecule (the spatial arrangement of atoms) is considered during profiling and analogue searching. Selecting "ignore stereo" will group chemicals based solely on their connectivity, while "account stereo" will treat different stereoisomers as distinct chemicals, which can be critical for endpoints where stereochemistry influences toxicity [29].

Q5: The Toolbox Client starts and shows a splash screen, but then the application window disappears. How can I fix this?

This is a known issue, often related to a conflict with the .NET framework or regional system settings. A dedicated fix is available on the official QSAR Toolbox "Known Issues" webpage. The solution involves following specific instructions, which may include repairing the .NET framework installation or applying a patch [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Database Connection Issues

Problem: The Toolbox Server cannot connect to the PostgreSQL database, especially when they are on separate machines. An error such as "no pg_hba.conf entry for host..." may appear [31].

Solution:

- Locate the

pg_hba.conffile on the machine hosting the PostgreSQL database (typically in the PostgreSQLdatadirectory). - Add a line to the bottom of the file to allow connections from the Toolbox Server machine:

host all qsartoolbox <ToolboxServerHost> md5(Replace<ToolboxServerHost>with the IP address or hostname of the Toolbox Server computer). - Save the file and restart the PostgreSQL service.

- Restart the QSAR Toolbox Server application [31].

Performance and Profiling Accuracy

Problem: Profiling results show incorrect, extremely high parameter values [31].

Solution: This is a known bug in specific versions (e.g., Toolbox 4.6) related to how regional settings on a computer handle decimal numbers. While the displayed value is wrong, the underlying calculation used for profiling is correct. This issue is scheduled to be fixed in a subsequent release [31].

Problem: Uncertain about the reliability of profilers for category formation.

Solution: The performance of profilers can be assessed using statistical measures. Research indicates that while many profilers are fit-for-purpose, some structural alerts may require refinement. When building categories for critical endpoints like mutagenicity or skin sensitization, consult scientific literature on profiler performance, such as studies evaluating their sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy [32].

Table 1: Example Performance Metrics of Selected Profilers from a Scientific Study [32]

| Profiler Endpoint | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutagenicity (Ames test) | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.63 |

| Carcinogenicity | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.37 |

| Skin Sensitisation | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.66 |

Installation and Deployment

Problem: Database deployment fails or deadlocks on non-English versions of Windows [31].

Solution: This affects the portable deployment mode. A patch for the DatabaseDeployer is available for download from the official "Known Issues" page. Decompress the patch files into the Database sub-folder of your Toolbox installation directory, overwriting the existing files, and then restart the deployment process [31].

Experimental Protocols for Regulatory Predictions

Protocol for Predicting Acute Toxicity to Fish Using the Automated Workflow

This protocol outlines the use of the Automated Workflow (AW) for predicting 96-hour LC50 in fathead minnow, a common requirement under regulations like REACH [33].

1. Objective: To reliably predict acute fish toxicity for a target chemical without animal testing, using read-across from analogues identified by the Toolbox.

2. Methodology:

- Input: Launch the Automated Workflow for aquatic toxicity and define the target chemical by entering its CAS number, name, or by drawing its structure [33].

- Profiling: The AW automatically applies relevant profilers to identify the target chemical's structural features and potential Mode of Action (MOA) [30] [33].

- Data Collection: The system searches its extensive databases (containing over 3.2 million experimental data points) for experimental LC50 values [30].

- Category Definition (Analogue Identification): The AW identifies a category of structurally similar chemicals (analogues) that share the same MOA and have experimental LC50 data [33].

- Data Gap Filling: The Toolbox performs a prediction for the target chemical, typically using read-across from the identified analogues. The prediction is based on the experimental data from the source chemicals within the defined category [30] [33].

3. Validation: A study evaluating this AW found its predictive performance to be acceptable and comparable to published QSAR models, with most prediction errors falling within expected inter-laboratory variability for the experimental test itself [33].

Protocol for Building a Category for Read-Across

This general protocol describes the manual steps for building a chemically meaningful category to fill a data gap via read-across, a core functionality of the Toolbox [30].

1. Objective: To group a target chemical with source analogues based on structural and mechanistic similarity for a specific endpoint (e.g., skin sensitization).

2. Methodology:

- Input and Profiling: Manually input the target chemical and run a suite of relevant profilers. These profilers identify structural alerts, functional groups, and properties related to the endpoint [30] [32].

- Data Collection: Use the "Endpoint" tool to gather existing experimental data for the target endpoint from the Toolbox's databases.

- Analogue Searching and Category Building: Use the "Category Definition" module to find analogues. This can be done by:

- Similar chemical search: Using molecular similarity indices.

- Same profiler outcome: Finding chemicals that share the same key structural alert or mechanistic profile as the target [30].

- Category Consistency Assessment: Critically assess the formed category. Remove chemicals that differ significantly from the target in structure or mechanism, even if they were initially grouped. This step is crucial for justifying the read-across [30].

- Data Gap Filling and Reporting: Use the "Data Gap Filling" module to perform the read-across prediction. Finally, generate a comprehensive report detailing the target, source analogues, rationale for category membership, and the final prediction to ensure transparency for regulatory submission [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key In Silico Tools and Data within the QSAR Toolbox

| Tool / Resource | Function in Chemical Assessment |

|---|---|

| Structural Profilers | Identify key functional groups, fragments, and structural alerts that are associated with specific toxicological mechanisms or modes of action (e.g., protein binding alerts for skin sensitization) [30] [32]. |

| Mechanistic Profilers | Categorize chemicals based on their predicted interaction with biological systems, such as their molecular initiating event (MIE) within an Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) [34]. |

| Metabolic Simulators | Predict (a)biotic transformation products and metabolites of the parent chemical, which may be more toxicologically active, ensuring the assessment considers potential activation [30]. |

| Experimental Databases | Provide a vast repository of high-quality, curated experimental data for physicochemical, toxicological, and ecotoxicological endpoints, serving as the foundation for read-across [30]. |

| External QSAR Models | Integrated models that can be executed to generate additional, model-based evidence for a chemical's property or hazard, supporting the overall weight-of-evidence [30]. |

| Reporting Tools (Data Matrix, QPRF) | Generate transparent and customizable reports that document the entire assessment workflow, which is critical for regulatory acceptance and justification of the predictions made [30] [35]. |

| Syuiq-5 | Syuiq-5, CAS:188630-47-9, MF:C20H22N4, MW:318.4 g/mol |

| 16-Keto aspergillimide | 16-Keto aspergillimide, MF:C20H27N3O4, MW:373.4 g/mol |

The Role of Machine Learning in Predicting Toxicity and Prioritizing Chemicals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Machine Learning Fundamentals

What are the main types of machine learning used in predictive toxicology?

Machine learning in toxicology primarily uses supervised learning for classification (e.g., carcinogen vs. non-carcinogen) and regression (e.g., predicting toxicity potency) tasks. Deep learning models are increasingly applied to analyze complex data structures like molecular graphs and high-throughput screening data. Transfer learning is also employed to leverage knowledge from data-rich domains for endpoints with limited data [36].

How does AI improve upon traditional toxicity testing methods?

AI addresses key limitations of traditional methods, which are often costly, low-throughput, and prone to inaccurate human extrapolation due to species differences [37]. ML models can integrate diverse, large-scale datasets—including omics profiles, chemical properties, and clinical data—to uncover complex toxicity mechanisms and provide faster, more accurate risk identification, thereby reducing reliance on animal testing in line with the 3Rs principle [37] [36].

Data Management and Quality

Which databases are essential for building ML models in toxicology?

The table below summarizes key databases used for sourcing chemical and toxicological data.

| Database Name | Key Data Contained | Primary Application in ML Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| TOXRIC [36] | Acute/chronic toxicity, carcinogenicity data (human, animal, aquatic) | Model training and validation for various toxicity endpoints |

| DrugBank [36] | Drug data, targets, pharmacological properties, ADMET information | Predicting drug-specific toxicity and adverse reactions |

| ChEMBL [36] | Bioactive molecule data, drug-like properties, ADMET information | Building quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models |

| DSSTox [36] | Chemical structures, standardized toxicity values (Toxval) | Chemical risk assessment and curation of high-quality datasets |

| FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) [36] | Post-market adverse drug reaction reports | Identifying clinical toxicity signals and drug safety monitoring |

What are the most common data quality issues, and how can they be resolved?

A major challenge is the variable reliability and reporting standards of academic research data, which often does not follow regulatory standardized test guidelines [38]. To resolve this, consult the OECD guidance for practical considerations on study design, data documentation, and reporting to improve regulatory uptake [38]. For model training, implement rigorous data preprocessing: clean data, handle missing values, and apply feature scaling to mitigate biases and improve model generalizability.

Chemical Prioritization

How are chemicals prioritized for risk assessment by regulatory bodies?

Regulatory agencies use structured, science-based prioritization methods. The U.S. EPA, under TSCA, designates chemicals as High-Priority for risk evaluation if they may present an unreasonable risk, or Low-Priority if risk evaluation is not currently warranted [39]. The FDA uses Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) for chemicals in food, scoring them based on hazard, exposure, and public health risk potential to focus resources effectively [40].

Can machine learning be integrated into these regulatory frameworks?

Yes, prediction-based prioritization is a recognized strategy. Machine learning and QSAR models can estimate toxicological risk or environmental concentration, helping to rank chemicals for further testing and assessment [41]. This is particularly valuable for non-target screening in environmental analysis, where the number of chemical features is vast [41].

Model Development and Validation

What is the best way to validate an ML model for toxicity prediction?

Robust validation is critical. Use cross-validation during training to tune parameters and assess performance. Most importantly, perform external validation using a completely separate, blinded dataset not seen during model development to test its real-world generalizability [37]. Benchmark your model's performance against traditional methods and existing models to demonstrate its value [37].

Why is my model performing well on training data but poorly on new chemicals?

This is a classic sign of overfitting, where the model has memorized noise and specifics of the training data instead of learning generalizable patterns. It can also stem from data mismatch, where new chemicals are structurally or functionally different from those in the training set. Solutions include simplifying the model, increasing the amount and diversity of training data, and applying regularization techniques [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Model Performance and Overfitting

Symptoms:

- High accuracy on training data, low accuracy on validation/test data.

- Predictions are inconsistent and seem random.

| Step | Action | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Simplify the model by reducing the number of features or using regularization (L1/L2). | Reduces model complexity to prevent learning noise [36]. |

| 2 | Augment your training set with more diverse chemical structures and data. | Provides a broader basis for learning generalizable rules [36]. |

| 3 | Apply techniques like cross-validation during training to ensure the model is evaluating on held-out data. | Gives a more reliable estimate of model performance on unseen data [37]. |

Data Quality and Integration Failures

Symptoms:

- Model fails to converge or produces consistently erroneous predictions.

- Significant performance drop when integrating new data sources.

| Step | Action | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perform data curation: standardize chemical structures (e.g., SMILES), remove duplicates, and correct errors. | Ensures data consistency and integrity, which is foundational for reliable models [38]. |

| 2 | Check for dataset shift between training and new data distributions. | Identifies mismatches in chemical space that degrade performance. |

| 3 | Use a governed context layer to define data relationships, metrics, and joins consistently across the organization. | Maintains data consistency and improves interpretability, as seen in platforms like Querio [42]. |

Lack of Model Interpretability

Symptoms:

- Inability to explain or justify model predictions to regulators or colleagues.

- Model identifies spurious correlations instead of causally relevant features.

| Step | Action | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Employ explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations). | Reveals which chemical features (e.g., functional groups) drove a specific prediction [37]. |

| 2 | Validate model-derived features against known toxicological alerts and structural fragments. | Grounds model output in established scientific knowledge, building trust [36]. |

| 3 | Use simpler, interpretable models (e.g., decision trees) as baselines before moving to complex deep learning models. | Provides a benchmark and a more transparent alternative [37]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Training

Protocol 1: Building a QSAR Model for Acute Toxicity

Objective: To create a machine learning model that predicts acute toxicity (e.g., LD50) based on chemical structure.

Materials & Reagents:

- Hardware: Standard computer workstation with sufficient GPU/CPU.

- Software: Python environment with libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, RDKit, DeepChem).

- Data Source: TOXRIC or PubChem database [36].

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Download acute toxicity data (e.g., LD50 values). Standardize chemical structures (e.g., convert to canonical SMILES) and remove inorganic salts and duplicates.

- Descriptor Calculation: Use cheminformatics software (e.g., RDKit) to compute molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological surface area) or generate molecular fingerprints.

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset randomly into a training set (e.g., 80%) and a hold-out test set (e.g., 20%). Ensure structural diversity is represented in both sets.

- Model Training: Train a selected algorithm (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) on the training set using molecular descriptors/fingerprints as features and the toxicity endpoint as the target variable. Optimize hyperparameters via cross-validation.

- Model Validation: Predict the toxicity values for the hold-out test set. Evaluate performance using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R².

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: Implementing a Chemical Prioritization Workflow

Objective: To prioritize chemicals for experimental testing using a multi-criteria machine learning approach.

Materials & Reagents:

- Data Sources: DSSTox database [36], ICE database [36], and in-house experimental data.

- Tools: Data visualization platform (e.g., Querio [42]) for interactive analysis.

Methodology:

- Data Assembly: Compile a dataset for each chemical, including structural alerts, predicted toxicity scores from various models (e.g., carcinogenicity, endocrine disruption), physicochemical properties (e.g., persistence, bioaccumulation potential), and estimated exposure levels.

- Feature Scoring: Normalize each criterion and assign a quantitative score. Weights can be applied to different features based on regulatory requirements (e.g., higher weight for persistence and bioaccumulation as per EPA TSCA [39]).

- Priority Ranking: Use a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) method or a ranking algorithm to aggregate the scores into a single priority index for each chemical [40] [41].

- Visualization & Analysis: Input the results into a data visualization tool. Create an interactive dashboard to explore the chemicals, filter by specific properties, and identify the top candidates for further testing [42].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

The table below lists key reagents, data sources, and tools used in ML-driven toxicology and chemical prioritization.

| Category | Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | TOXRIC, DSSTox [36] | Provides curated, high-quality toxicity data for model training and validation. |

| DrugBank, ChEMBL [36] | Offers drug-specific bioactivity and ADMET data for pharmaceutical toxicity prediction. | |

| FAERS [36] | Supplies real-world post-market adverse event data for clinical toxicity signal detection. | |

| Computational Tools | Python/R Libraries (scikit-learn, RDKit) [36] | Provides algorithms and cheminformatics functions for building and validating predictive models. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | A software application that facilitates the use of (Q)SAR methodologies for regulatory purposes. | |

| Analysis & Visualization | AI Data Visualization (e.g., Querio) [42] | Enables natural language querying and automated dashboard creation for insight generation. |

| Regulatory Guidance | OECD Guidance on Research Data [38] | Provides frameworks for evaluating and incorporating academic research data into regulatory assessments. |

| EPA TSCA Prioritization [39] | Informs the selection of chemicals for risk evaluation based on specific hazard and exposure criteria. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is an Integrated Approach to Testing and Assessment (IATA)? An IATA is a flexible framework for chemical safety assessment that integrates and translates data derived from multiple methods and sources [43]. It is designed to conclude on the toxicity of chemicals by combining existing information from scientific literature with new data generated from traditional or novel testing methods to fill specific data gaps for a given regulatory scenario [44].

FAQ 2: How do IATAs help address data gaps in chemical assessments? IATAs allow for the use of various data sources to fill knowledge gaps without necessarily relying on new animal studies. This can include using existing data, new approach methodologies (NAMs), and computational models [44]. Furthermore, new guidance supports the use of academic research data, which can contribute essential information to fill these gaps and support efficient decision-making [38].

FAQ 3: What are the core components of an IATA? Core components of an IATA can include [44] [43]:

- Existing data from scientific literature or other resources.

- New data from traditional toxicity tests.

- New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): Such as high-throughput screening, high-content imaging, and computational models like in silico methods.

- Defined Approaches (DAs): Rule-based approaches that make predictions based on multiple, predefined data sources.

- A degree of expert judgment for data interpretation and integration.