Bioinformatics in Ecotoxicology: Computational Approaches for Predicting Chemical Hazards and Enhancing Drug Safety

This article explores the transformative role of bioinformatics and computational methods in modern ecotoxicology.

Bioinformatics in Ecotoxicology: Computational Approaches for Predicting Chemical Hazards and Enhancing Drug Safety

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of bioinformatics and computational methods in modern ecotoxicology. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how these approaches are revolutionizing the prediction of chemical effects on populations, communities, and ecosystems. The scope spans from foundational databases and exploratory data analysis to advanced machine learning applications, troubleshooting of computational models, and validation against empirical data. By synthesizing key methodologies and resources, this review provides a comprehensive guide for leveraging in silico tools to support environmental risk assessment, reduce animal testing, and accelerate the development of safer chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

Foundations and Data Landscapes: Core Bioinformatics Resources for Ecotoxicology

The field of ecotoxicology is increasingly reliant on bioinformatics and computational approaches to understand the effects of chemical stressors on ecological systems. The ECOTOX Knowledgebase, maintained by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), serves as a critical repository for curated toxicity data, supporting this data-driven evolution [1]. It provides a comprehensive, publicly accessible resource that integrates high-quality experimental data from the scientific literature, enabling researchers to move from exploratory analyses to predictive modeling and regulatory application.

Compiled from over 53,000 scientific references, ECOTOX contains more than one million test records covering 13,000 aquatic and terrestrial species and 12,000 chemicals [1]. This massive compilation supports the development of adverse outcome pathways (AOPs), quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models, and cross-species extrapolations that are fundamental to modern ecological risk assessment [1] [2]. The Knowledgebase is particularly valuable in an era where omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) are generating unprecedented amounts of molecular-level data that require contextualization with higher-level ecological effects [2] [3].

Table 1: Key Statistics of the ECOTOX Knowledgebase (as of 2025)

| Metric | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total References | 53,000+ | Comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed literature |

| Test Records | 1,000,000+ | Extensive data for meta-analysis and modeling |

| Species Covered | 13,000+ | Ecologically relevant aquatic and terrestrial organisms |

| Chemicals | 12,000+ | Diverse single chemical stressors |

| Update Frequency | Quarterly | Regular incorporation of new data and features |

ECOTOX Knowledgebase Functionality and Access

Core Features and User Interface

The ECOTOX Knowledgebase provides several interconnected features designed to accommodate different user needs and levels of specificity. Its web interface offers multiple pathways for data retrieval, from targeted searches to exploratory data analysis [1].

- Search Feature: This function allows targeted queries for data on specific chemicals, species, effects, or endpoints. Users can refine searches using 19 different parameters and customize output selections from over 100 data fields. Each chemical record links to the EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard for additional physicochemical properties and related data [1].

- Explore Feature: When users lack precise search parameters, the Explore feature enables broader investigation by chemical, species, or effects. This flexible approach supports hypothesis generation and data mining activities fundamental to research planning and gap analysis [1].

- Data Visualization: Interactive plotting tools allow users to visualize results dynamically. Features include hover-over data points for detailed information and zoom capabilities for examining specific data sections, facilitating rapid pattern recognition and outlier identification [1].

Applications in Ecotoxicology Research and Regulation

The ECOTOX Knowledgebase supports diverse applications across research, risk assessment, and regulatory decision-making, bridging the gap between raw experimental data and actionable scientific insights [1].

- Chemical Assessment and Criteria Development: For over 20 years, ECOTOX has served as a primary source for developing chemical benchmarks for water and sediment quality assessments. It directly supports the derivation of Aquatic Life Criteria protecting freshwater and saltwater organisms from both short-term and long-term chemical exposures [1].

- Ecological Risk Assessment: The database informs chemical registration and re-registration processes under various regulatory frameworks. It also aids in chemical prioritization and assessment under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) by providing consolidated toxicity evidence across taxonomic groups [1].

- Cross-Species Extrapolation and Modeling: ECOTOX data enables the development and validation of models that extrapolate from in vitro to in vivo effects and across species. The Knowledgebase is particularly valuable for building QSAR models that predict toxicity based on chemical structure, and for conducting meta-analyses to guide future research directions [1] [2].

ECOTOX Query Workflow: A flowchart depicting the systematic process for retrieving data from the ECOTOX Knowledgebase, from defining data needs to exporting final results.

Application Note: Transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPOD) Derivation Using ECOTOX Data

Experimental Background and Rationale

The integration of omics technologies into ecotoxicology has created new opportunities for developing more sensitive and mechanistic chemical safety assessments. Transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPOD) derivation represents a promising approach that uses whole-transcriptome responses to chemical exposure to determine quantitative threshold values for toxicity [3]. This method aligns with the growing emphasis on New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that reduce reliance on traditional animal testing while providing mechanistic insights [1] [3].

A recent case study demonstrated the application of ECOTOX data in validating tPOD values for tamoxifen using zebrafish embryos [3]. The derived tPOD was in the same order of magnitude but slightly more sensitive than the No Observed Effect Concentration (NOEC) from a conventional two-generation fish study. Similarly, research with rainbow trout alevins found that tPOD values were equally or more conservative than chronic toxicity values from traditional tests [3]. These findings support the use of embryo-derived tPODs as conservative estimations of chronic toxicity, advancing the 3R principles (Replace, Reduce, Refine) in ecotoxicological testing [3].

Protocol: tPOD Derivation Using Zebrafish Embryos

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for tPOD Derivation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish Embryos | In vivo model system | 0-6 hours post-fertilization (hpf); wild-type or specific strains |

| Test Chemical | Stressor of interest | High purity (>95%); prepare stock solutions in appropriate vehicle |

| Vehicle Control | Control for solvent effects | DMSO (≤0.1%), ethanol, or water as appropriate |

| Embryo Medium | Maintenance of embryos during exposure | Standard reconstituted water with specified ionic composition |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality RNA | Column-based methods with DNase treatment |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Poly-A selection or rRNA depletion protocols |

| Sequencing Platform | Transcriptome profiling | Illumina-based platforms for high-throughput sequencing |

| Bioinformatics Software | Data analysis and tPOD calculation | R packages (e.g., DRomics), specialized pipelines |

Procedure:

Experimental Design

- Exposure Concentrations: Select a geometrically spaced concentration series based on range-finding tests (typically 5-8 concentrations).

- Replication: Include a minimum of 3 biological replicates per treatment group, with each replicate containing a pool of 15-30 embryos.

- Controls: Include both vehicle controls (for solvent effects) and negative controls (untreated embryos).

Chemical Exposure

- Exposure Initiation: Transfer 6 hpf embryos to 24-well plates containing 2 mL of exposure solution per well.

- Exposure Conditions: Maintain at 28°C with a 14:10 light:dark photoperiod for 96 hours without feeding.

- Solution Renewal: Renew exposure solutions every 24 hours to maintain chemical concentration and water quality.

RNA Isolation and Sequencing

- Sample Collection: At 96 hpf, collect pools of embryos (n=15-30) from each replicate, rinse in clean embryo medium, and preserve in RNA stabilization reagent at -80°C.

- RNA Extraction: Isolve total RNA using column-based methods with DNase treatment; verify RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0) and quantity using appropriate instrumentation.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare mRNA sequencing libraries using standardized kits and sequence on an Illumina platform to a minimum depth of 25 million reads per sample.

Bioinformatic Analysis and tPOD Calculation

- Transcript Quantification: Map reads to the reference genome (GRCz11) and generate count matrices using alignment-free (e.g., Salmon) or alignment-based (e.g., STAR) methods.

- Differential Expression: Identify significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using appropriate statistical packages (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR) with a false discovery rate (FDR) of < 0.05.

- Benchmark Dose (BMD) Modeling: Input normalized counts for significantly altered genes into the DRomics package in R to fit dose-response models and calculate BMD values.

- tPOD Determination: Derive the overall tPOD as the lower 95% confidence bound of the median BMD (BMDL) for the sensitive gene set (typically the 10th-20th percentile of all BMD values).

tPOD Derivation Protocol: A workflow diagram illustrating the key steps in deriving a transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPOD) using zebrafish embryos and integrating data with ECOTOX Knowledgebase.

Data Integration and Analysis Protocols

Protocol: Cross-Species Extrapolation Using ECOTOX Data

Objective: Utilize ECOTOX data to extrapolate toxicity information across taxonomic groups, addressing data gaps for untested species.

Procedure:

Data Extraction from ECOTOX

- Identify a chemical of interest and retrieve all available toxicity data using the Search feature.

- Apply filters for relevant toxicity endpoints (e.g., LC50, EC50, NOEC) and exposure durations.

- Export data in a structured format (CSV or Excel) for analysis.

Taxonomic Analysis

- Classify species by phylum, class, and family to identify phylogenetic patterns in sensitivity.

- Calculate mean toxicity values and coefficients of variation for each taxonomic group.

- Identify indicator species with consistently high sensitivity across multiple chemicals.

Species Sensitivity Distribution (SSD) Modeling

- Fit cumulative distribution functions to toxicity data across species for specific chemical-endpoint combinations.

- Derive hazard concentrations (e.g., HC5 - hazardous to 5% of species) for protective risk assessment.

- Compare SSDs across chemical classes to identify trends in taxonomic selectivity.

Table 3: Cross-Species Toxicity Comparison for Model Chemicals (Representative Data)

| Chemical | Taxonomic Group | Species | Endpoint | Value (μg/L) | Exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium | Chordata (Fish) | Oncorhynchus mykiss | LC50 | 4.5 | 96-hour |

| Arthropoda (Crustacean) | Daphnia magna | EC50 | 1.2 | 48-hour | |

| Mollusca (Bivalve) | Mytilus edulis | EC50 | 15.8 | 96-hour | |

| Copper | Chordata (Fish) | Pimephales promelas | LC50 | 32.1 | 96-hour |

| Arthropoda (Crustacean) | Daphnia pulex | EC50 | 8.5 | 48-hour | |

| Chlorophyta (Algae) | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | EC50 | 15.3 | 72-hour | |

| 17α-Ethinyl Estradiol | Chordata (Fish) | Danio rerio | NOEC | 0.5 | Chronic |

| Arthropoda (Crustacean) | Daphnia magna | NOEC | 100 | Chronic | |

| Mollusca (Gastropod) | Lymnaea stagnalis | NOEC | 10 | Chronic |

Protocol: Meta-Analysis of Omics Data in Ecotoxicology

Objective: Synthesize findings from transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic studies to identify conserved stress responses across species.

Procedure:

Literature Curation and Data Integration

- Conduct systematic literature search using defined keywords (e.g., "ecotox" AND "transcriptom", "proteom", "metabolom") across databases (Google Scholar, Web of Science) [2].

- Extract relevant studies (following the PRISMA guidelines) and categorize by omics layer, species, stressor, and molecular pathways.

- Integrate ECOTOX data with omics studies to link molecular responses to adverse outcomes at higher biological levels.

Cross-Species Pathway Analysis

- Map differentially expressed molecules to conserved pathways using KEGG, GO, and Reactome databases.

- Identify orthologous genes across species to enable direct comparison of molecular responses.

- Use clustering algorithms to detect conserved stress response modules across taxonomic groups.

Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Development

- Organize molecular initiating events, key events, and adverse outcomes into AOP frameworks.

- Weight evidence from multiple studies and species using the OECD AOP development guidelines.

- Identify critical data gaps for experimental validation across multiple species.

The application of these protocols demonstrates how ECOTOX serves as both a standalone resource and a complementary database that adds ecological context to omics-based discoveries. This integration is essential for advancing predictive ecotoxicology and developing more efficient strategies for chemical safety assessment in the era of bioinformatics [1] [2] [3].

The application of bioinformatics in ecotoxicology represents a paradigm shift from traditional, observation-based toxicology to a mechanistically-driven science. This transition is powered by toxicogenomics—the integration of genomic technologies with toxicology to understand how chemicals perturb biological systems. By analyzing genome-wide responses to environmental contaminants, researchers can decipher Mode of Action (MoA), identify early biomarkers of effect, and prioritize chemicals for regulatory attention. The CompTox Chemicals Dashboard serves as the central computational platform enabling these analyses by providing curated data for over one million chemicals, bridging chemistry, toxicity, and exposure information essential for modern ecological risk assessment [4] [5] [6].

CompTox Chemicals Dashboard: Capabilities and Data Structure

The CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, is a publicly accessible hub that consolidates chemical data to support computational toxicology research. Its core function is to provide structure-curated, open data that integrates physicochemical properties, environmental fate, exposure, in vivo toxicity, and in vitro bioassay data through a robust cheminformatics layer [6]. The underlying DSSTox database enforces strict quality controls to ensure accurate substance-structure-identifier mappings, addressing a well-recognized challenge in public chemical databases [5] [6].

Key Data Streams and Quantitative Content

Table: Major Data Streams Accessible via the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard

| Data Category | Specific Data Types | Source/Model | Record Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Substance Records | Structure, identifiers, lists | DSSTox | ~1,000,000+ [4] [7] [5] |

| Physicochemical Properties | LogP, water solubility, pKa | OPERA, TEST, ACD/Percepta | Measured & predicted [5] |

| Environmental Fate & Transport | Biodegradation, bioaccumulation | EPI Suite, OPERA | Predicted values [5] |

| Toxicity Values | In vivo animal study data | ToxValDB | Versioned releases (e.g., v9.6.2) [5] [8] |

| In Vitro Bioactivity | HTS assay data (AC50, AUC) | ToxCast/Tox21 (invitroDB) | ~1,000+ assays [5] [8] |

| Exposure Data | Use categories, biomonitoring | CPDat, ExpoCast | Functional use, product types [5] |

| Toxicokinetics | IVIVE parameters, half-life | HTTK | High-throughput predictions [5] |

The Dashboard supports advanced search capabilities including mass and formula-based searching for non-targeted analysis, batch searching for thousands of chemicals, and structure/substructure searching [4] [8]. Recent updates (as of 2025) have enhanced ToxCast data integration, added cheminformatics modules, and expanded DSSTox content with over 36,000 new chemicals [8].

Toxicogenomics databases provide molecular response profiles that illuminate biological pathways perturbed by chemical exposure. The DILImap resource represents a purpose-built transcriptomic library for drug-induced liver injury research, comprising 300 compounds profiled at multiple concentrations in primary human hepatocytes using RNA-seq [9]. This design captures dose-responsive transcriptional changes across pharmacologically relevant ranges, enabling development of predictive models like ToxPredictor which achieved 88% sensitivity at 100% specificity in blind validation [9].

The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) offers another foundational resource by curating chemical-gene-disease relationships from scientific literature. CTD enables the construction of CGPD tetramers (Chemical-Gene-Phenotype-Disease blocks) that computationally link chemical exposures to molecular events and adverse outcomes [10]. This framework supports chemical grouping based on shared mechanisms rather than just structural similarity.

Multi-Omics Approaches in Ecotoxicology

Ecotoxicogenomics extends these approaches to ecologically relevant species, though challenges remain due to less complete genome annotations compared to mammalian models [11] [12]. The integration of transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics provides complementary insights at different biological organization levels:

- Transcriptomics: Measures mRNA expression changes using microarrays or RNA-seq; reveals initial stress responses but may not reflect functional protein levels [11]

- Proteomics: Analyzes protein expression and post-translational modifications via 2D gels and mass spectrometry; captures functional molecular effectors [11]

- Metabolomics: Profiles low-molecular-weight metabolites through NMR or MS; represents integrated physiological status and functional outcomes [11]

Experimental Protocols: Toxicogenomics Workflow

Protocol: Transcriptomic Profiling Using DILImap Framework

Objective: Generate dose-responsive transcriptomic data for chemical MoA characterization and DILI prediction [9].

Materials:

- Primary Human Hepatocytes (PHHs): Sandwich-cultured to maintain hepatic functionality (e.g., metabolic activity, bile canaliculi formation)

- Chemical Library: 300+ compounds with clinical DILI annotations (positive/negative controls)

- Cell Viability Assays: ATP content and LDH release measurements for cytotoxicity assessment

- RNA Isolation Kit: High-quality total RNA extraction with DNAse treatment

- RNA-seq Library Prep: Strand-specific protocols with ribosomal RNA depletion

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina-based sequencing (minimum 30M reads/sample)

- Bioinformatics Tools: DESeq2 for differential expression, WikiPathways for enrichment analysis [9]

Procedure:

- Hepatocyte Culture: Plate PHHs in collagen-sandwich configuration and maintain for 4-7 days to stabilize hepatic functions [9]

- Dose Selection:

- Conduct preliminary dose-range finding using ATP and LDH assays (6 concentrations)

- Calculate ICâ‚â‚€ values from dose-response curves

- Select 4 test concentrations: therapeutic Cmax to just below ICâ‚â‚€ (highest non-cytotoxic dose) [9]

- Chemical Exposure:

- Treat triplicate cultures with test compounds or vehicle control (DMSO) for 24 hours

- Use 24-hour exposure as optimal balance between transcriptional response strength and hepatocyte dedifferentiation concerns [9]

- RNA Quality Control:

- Extract total RNA using column-based methods

- Assess RNA integrity (RIN >8.0) and quantify

- Exclude samples with high mitochondrial RNA content indicating poor viability [9]

- Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Deplete ribosomal RNA to enhance mRNA representation

- Prepare stranded RNA-seq libraries with unique dual indexing

- Sequence on Illumina platform (2×150 bp reads)

- Data Analysis:

- Align reads to reference genome (STAR aligner)

- Count gene-level reads (featureCounts)

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DESeq2, FDR <0.05) [9]

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis (WikiPathways)

Protocol: Chemical Grouping Using CGPD Tetramers

Objective: Identify and cluster chemicals with similar molecular mechanisms using public toxicogenomics data [10].

Materials:

- Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD): Source of curated chemical-gene-phenotype-disease interactions

- PubChem Database: Provides chemical identifiers and structural information

- Orthology Database: NCBI gene orthologs for cross-species mapping

- SQLite Database: Local storage for integrated data

- Clustering Algorithms: Hierarchical clustering or community detection methods

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition:

- Download CTD interaction tables (chemical-gene, chemical-phenotype, chemical-disease)

- Extract PubChem compound data using Identifier Exchange Service [10]

- Identifier Mapping:

- Map CTD MeSH chemical IDs to PubChem CIDs (~85% success rate)

- Apply orthology mapping to standardize gene identifiers across species (human, mouse, rat) [10]

- CGPD Tetramer Construction:

- Link chemicals to interacting genes (direct or expression changes)

- Connect genes to phenotype outcomes (GO terms)

- Associate phenotypes with relevant diseases [10]

- Chemical Similarity Scoring:

- Calculate Jaccard similarity indices based on shared gene targets

- Incorporate phenotypic similarity metrics

- Cluster Analysis:

- Apply hierarchical clustering with optimal leaf ordering

- Validate clusters against established cumulative assessment groups (CAGs) [10]

- Mechanistic Annotation:

- Interpret clusters using pathway enrichment (KEGG, Reactome)

- Identify key molecular initiators and adverse outcome pathways

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Toxicogenomics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Application | Access Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | CompTox Dashboard, DSSTox, PubChem | Chemical structure, property, and identifier curation | https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard [4] |

| Toxicogenomics Data | DILImap, CTD, TG-GATES | Transcriptomic response data for chemical exposures | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65690-3 [9] |

| Pathway Resources | WikiPathways, KEGG, GO | Biological pathway annotation and enrichment analysis | https://wikipathways.org [9] |

| Analysis Tools | DESeq2, ToxPredictor, OECD QSAR Toolbox | Differential expression, machine learning prediction, read-across | Bioconductor, GitHub [9] |

| Cell Models | Primary Human Hepatocytes, HepaRG, HepG2 | Physiologically relevant in vitro toxicity testing | Commercial vendors [9] [13] |

| Quality Control | RNA integrity assessment, orthology mapping | Data reliability and cross-species comparability | Laboratory protocols [9] [10] |

Workflow Visualizations

Toxicogenomics Data Generation and Application

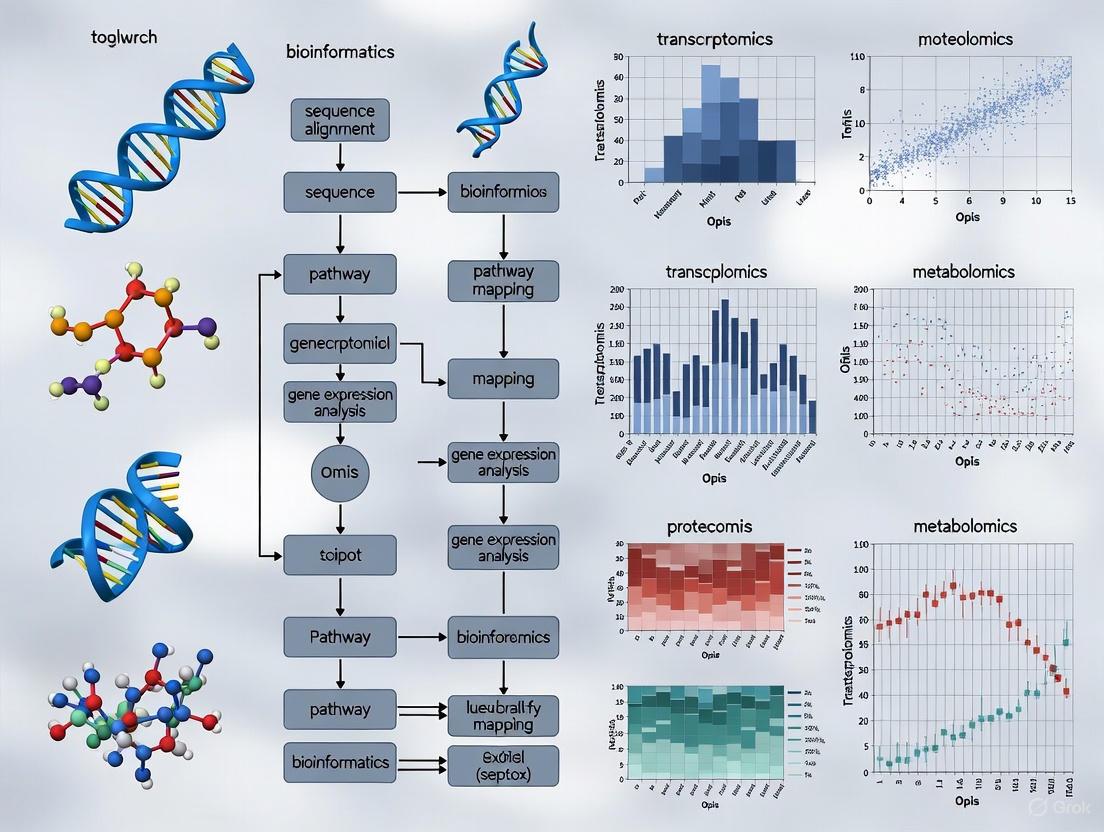

Workflow for Toxicogenomics: This diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from chemical exposure through molecular profiling to risk assessment.

CompTox Dashboard Data Integration

CompTox Dashboard Structure: This diagram shows how the DSSTox database serves as the core integration point for multiple data streams within the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, enabling various research applications.

Chemical Grouping Using CGPD Tetramers

Chemical Grouping Framework: This diagram outlines the process of creating chemical-gene-phenotype-disease (CGPD) tetramers from the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database to identify chemicals with similar mechanisms for cumulative assessment.

Systematic Review and FAIR Data Principles in Ecotoxicology

Application Note: Integrating Systematic Review with FAIR Data Principles

Systematic reviews represent the highest form of evidence within the hierarchy of research designs, providing comprehensive summaries of existing studies to answer specific research questions through minimized bias and robust conclusions [14]. In ecotoxicology, the need for assembled toxicity data has accelerated as the number of chemicals introduced into commerce continues to grow and regulatory mandates require safety assessments for a greater number of chemicals [15]. The integration of FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) with systematic review methodologies addresses critical challenges in ecological risk assessment by enhancing data transparency, objectivity, and consistency [15].

This application note outlines established protocols for conducting high-quality systematic reviews in ecotoxicology while implementing FAIR data principles throughout the research workflow. These methodologies are particularly valuable for researchers developing bioinformatics approaches in ecotoxicology, where computational models require high-quality, standardized data for training and validation [16] [17]. The ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX) exemplifies this integration, serving as the world's largest compilation of curated ecotoxicity data while employing systematic review procedures for literature evaluation and data curation [15].

Experimental Design and Workflow Integration

The systematic review process in ecotoxicology follows a structured workflow that aligns with both Cochrane Handbook standards and domain-specific requirements for ecological assessments [14]. Protocol registration at the initial stage enhances transparency and reduces reporting bias, while comprehensive search strategies across multiple databases ensure all relevant evidence is captured [14]. For ecotoxicological reviews, specialized databases like ECOTOX provide curated data from over 1.1 million test results across more than 12,000 chemicals and 14,000 species [15].

Recent advancements have incorporated artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches into the systematic review workflow, particularly during the study selection and data extraction phases [16]. Natural language processing algorithms can assist in screening large volumes of literature, while machine learning models can extract key methodological details and results using established controlled vocabularies [16] [15]. These computational approaches enhance both the efficiency of systematic reviews and the interoperability of resulting data, directly supporting FAIR principles.

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of Ecotoxicology Data Resources

| Resource Name | Data Volume | Chemical Coverage | Species Coverage | FAIR Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | >1 million test results | >12,000 chemicals | >14,000 species | Full FAIR alignment [15] |

| ADORE Benchmark Dataset | Acute toxicity for 3 taxonomic groups | Extensive chemical diversity | Fish, crustaceans, algae | ML-ready formatting [17] |

| CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | Integrated with ECOTOX | ~900,000 chemicals | Variable | DTXSID identifiers [17] |

Protocol: Conducting Systematic Reviews in Ecotoxicology

Research Question Formulation and Protocol Development

The initial phase of a systematic review requires precise research question formulation using structured frameworks. The PICOS framework (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study Design) provides a robust structure for defining review scope and inclusion criteria [14]. For ecotoxicological applications, an extended PICOTS framework incorporating Timeframe and Study Design is particularly valuable for accounting for ecological lag effects and appropriate experimental models [14].

Table 2: PICOTS Framework Application in Ecotoxicology

| PICOTS Element | Definition | Ecotoxicology Example |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Subject or ecosystem of interest | Daphnia magna cultures under standardized laboratory conditions |

| Intervention | Exposure or treatment | Sublethal concentrations of pharmaceutical contaminants (e.g., 1-10 μg/L) |

| Comparator | Control or alternative condition | Untreated control populations in identical media |

| Outcomes | Measured endpoints | Mortality, immobilization, reproductive inhibition (EC50 values) |

| Timeframe | Exposure and assessment duration | 48-hour acute toxicity tests following OECD guideline 202 |

| Study Design | Experimental methodology | Controlled laboratory experiments following standardized protocols |

Protocol development must specify:

- Inclusion/exclusion criteria with clear rationale

- Search strategy with complete syntax for all databases

- Data extraction fields aligned with analysis needs

- Quality assessment tools appropriate for ecotoxicology studies [14]

For bioinformatics applications, the protocol should explicitly define data formatting requirements and metadata standards to ensure computational reusability [17].

Literature Search and Study Selection

Comprehensive literature searching requires multiple database queries and supplementary searching techniques:

Primary Database Strategies:

- ECOTOX Knowledgebase using chemical identifiers (CAS RN, DTXSID) and taxonomic classifications [15]

- Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed using structured search syntax

- Specialized repositories for gray literature and regulatory studies

Search Syntax Example:

Study Selection Process:

- Duplicate removal using reference management software

- Title/abstract screening against predefined eligibility criteria

- Full-text assessment for final inclusion

- Data integrity verification for computational readiness [17]

The screening process should involve multiple independent reviewers with a predefined process for resolving conflicts through consensus or third-party adjudication [14]. For machine learning applications, study selection should prioritize data completeness and standardization to ensure model reliability [17].

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Standardized data extraction forms should capture both methodological details and quantitative results essential for evidence synthesis:

Essential Data Fields:

- Chemical identifiers (CAS RN, DTXSID, SMILES, InChIKey) [17]

- Test organism taxonomy (species, strain, life stage)

- Experimental conditions (media, temperature, pH, exposure duration)

- Endpoint type (LC50, EC50, NOEC) with values, units, and variance measures

- Quality and reliability indicators [15]

Risk of Bias Assessment: Ecological studies require domain-specific assessment tools evaluating:

- Internal validity: Experimental design, control appropriateness, confounding management

- External validity: Environmental relevance, test system complexity

- Reporting quality: Methodological completeness, data transparency [14]

The Klimisch score or similar reliability assessment frameworks provide structured approaches for evaluating study robustness in ecotoxicological contexts [15].

Systematic Review Workflow with FAIR Integration

Protocol: Implementing FAIR Data Principles

Findable and Accessible Data Management

Unique Identifiers Implementation:

- Chemical Identification: Utilize persistent identifiers including CAS RN, DSSTox Substance ID (DTXSID), and InChIKey to ensure precise chemical tracking across databases [15] [17].

- Taxonomic Standardization: Apply integrated taxonomic information system (ITIS) codes for consistent species identification and phylogenetic contextualization [17].

- Dataset Citation: Obtain digital object identifiers (DOIs) for curated datasets to facilitate formal citation and tracking.

Metadata Requirements: Rich metadata should comprehensively describe:

- Experimental methodologies and testing conditions

- Organism sourcing and acclimation procedures

- Analytical chemistry verification data

- Statistical analysis approaches

- Data provenance and curation history [15]

Accessibility Protocols:

- Deposit data in community-recognized repositories (ECOTOX, EnviroTox)

- Implement clear data licensing (Creative Commons, Open Data Commons)

- Provide multiple access modalities (web interface, API, bulk download) [15]

Interoperable and Reusable Data Structures

Data Standardization:

- Endpoint Harmonization: Apply consistent terminology for effects (mortality, immobilization, growth inhibition) and endpoints (LC50, EC50, NOEC) following OECD guideline definitions [17].

- Unit Conversion: Implement standardized concentration units (molar and mass-based) with explicit documentation of conversion factors and assumptions.

- Structural Data: Incorporate chemical structure representations (SMILES, InChI) to enable cheminformatics applications and read-across approaches [17].

Contextual Documentation: Comprehensive methodological descriptions should include:

- Test Guidelines: Specific protocol implementations (OECD, EPA, ISO)

- Temporal Factors: Exposure duration and measurement timepoints

- Environmental Parameters: Temperature, pH, water hardness, light conditions

- Statistical Methods: Effect calculation procedures and confidence estimation [15]

Machine-Actionable Formats:

- Structure data in standardized formats (JSON-LD, RDF) for computational access

- Implement application programming interfaces (APIs) for programmatic data retrieval

- Provide data dictionaries and schema documentation for reuse clarity [15]

FAIR Data Principles Implementation Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Ecotoxicology Systematic Reviews

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Systematic Reviews |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecotoxicology Databases | ECOTOX Knowledgebase [15] | Curated ecotoxicity data repository | Primary data source for effect concentrations and test conditions |

| ADORE Benchmark Dataset [17] | Machine learning-ready toxicity data | Training and validation of predictive models | |

| Chemical Registration | CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [17] | Chemical identifier integration | Cross-referencing and structure standardization |

| PubChem [17] | Chemical property database | SMILES notation and molecular descriptor generation | |

| Taxonomic Standardization | Integrated Taxonomic Information System | Species classification authority | Taxonomic harmonization across studies |

| Quality Assessment | Klimisch Scoring System [15] | Study reliability evaluation | Risk of bias assessment for included studies |

| PRISMA Guidelines [14] | Reporting standards framework | Transparent methodology and results documentation | |

| Data Analysis | R packages (metafor, meta) | Statistical meta-analysis | Quantitative evidence synthesis |

| Python scikit-learn [17] | Machine learning algorithms | Predictive model development from extracted data | |

| Punicic Acid | Punicic Acid, CAS:544-72-9, MF:C18H30O2, MW:278.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Procyanidin A1 | Procyanidin A1 (Proanthocyanidin A1) | Procyanidin A1 is a natural polyphenol for aging, cancer, and inflammation research. High purity, for research use only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications in Bioinformatics

Machine Learning Integration

The ADORE (Aquatic Toxicity Benchmark Dataset) exemplifies the intersection of systematic review methodology and bioinformatics applications [17]. This comprehensive dataset incorporates:

- Core ecotoxicological data on acute aquatic toxicity for fish, crustaceans, and algae

- Chemical descriptors including molecular representations and physicochemical properties

- Species-specific characteristics incorporating phylogenetic relationships

- Experimental conditions with standardized metadata for computational modeling [17]

For machine learning implementation, the dataset supports:

- Regression models predicting continuous toxicity values (LC50, EC50)

- Classification approaches categorizing chemicals into toxicity brackets

- Read-across methodologies leveraging chemical and biological similarity

- Uncertainty quantification through standardized data splitting strategies [17]

Multi-Omics Data Integration

Systematic reviews in modern ecotoxicology increasingly incorporate multi-omics technologies to elucidate mechanistic toxicity pathways:

Genomic Applications:

- Gene expression profiling through transcriptomics (RNA-seq) to identify differentially expressed genes under chemical stress [18]

- Epigenetic modifications detected via whole-genome sequencing approaches

- Population genomics assessing adaptive responses in exposed populations

Proteomic and Metabolomic Integration:

- Protein expression changes quantified through mass spectrometry (LC-MS, MALDI-TOF) [18]

- Metabolic pathway perturbations characterized via metabolomic profiling

- Multi-omics correlation networks integrating molecular responses across biological hierarchies [18]

The systematic review framework ensures rigorous evaluation of omics study quality and appropriate synthesis of mechanistic evidence across multiple experimental systems.

The integration of systematic review methodology with FAIR data principles establishes a robust foundation for evidence-based ecotoxicology and computational risk assessment. The structured approaches outlined in these application notes and protocols enhance methodological transparency, data quality, and research reproducibility while supporting the development of predictive bioinformatics models [15] [17].

Future advancements will likely focus on:

- Automated literature screening using natural language processing and machine learning classifiers

- Real-time evidence mapping dynamically updating systematic reviews as new studies emerge

- Knowledge graph integration linking chemical, biological, and toxicological entities in computable networks

- Domain-specific language models trained on ecotoxicology literature to enhance information extraction [16]

These developments will further accelerate the translation of ecotoxicological evidence into predictive models that support chemical safety assessment and environmental protection, ultimately reducing reliance on animal testing through robust in silico approaches [15] [17].

Identifying Data Gaps and Research Opportunities through Data Mining

Modern ecotoxicology is undergoing a paradigm shift, driven by the generation of complex, high-dimensional data from high-throughput omics technologies. Data mining, the computational process of discovering patterns, extracting knowledge, and predicting outcomes from large datasets, is essential to transform this data into actionable insights for environmental and human health protection [19]. The integration of data mining with bioinformatics approaches allows researchers to move beyond traditional, often isolated endpoints, towards a systems-level understanding of how pollutants impact biological systems across multiple levels of organization—from the genome to the ecosystem [18] [20]. This Application Note details protocols for leveraging data mining to identify critical data gaps and prioritize research in ecotoxicology, framed within the DIKW (Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom) framework for extracting wisdom from big data [20].

Data Mining Paradigms and Ecotoxicological Applications

Data mining algorithms can be broadly categorized into prediction and knowledge discovery paradigms, each containing sub-categories suited to different types of ecotoxicological questions [19]. The table below summarizes the primary data mining categories and their applications in ecotoxicology.

Table 1: Data Mining Paradigms and Their Ecotoxicological Applications

| Data Mining Category | Primary Objective | Example Algorithms | Application in Ecotoxicology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification & Regression | Predict categorical or continuous outcomes from input features [19]. | Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines, Artificial Neural Networks [19]. | Forecasting air quality indices; classifying chemical toxicity based on structural features [19]. |

| Clustering | Identify hidden groups or patterns in data without pre-defined labels [19]. | k-Means Clustering, Hierarchical Clustering [21] [19]. | Discovering novel modes of action by grouping chemicals with similar transcriptomic profiles [19]. |

| Association Rule Mining | Find frequent co-occurring relationships or patterns among variables in a dataset [19]. | APRIORI Algorithm [19]. | Identifying combinations of pollutant exposures frequently linked to specific adverse outcomes in epidemiological data [19]. |

| Anomaly Detection | Identify rare items, events, or observations that deviate from the majority of the data [19]. | Isolation Forests, Local Outlier Factor [19]. | Detecting abnormal biological responses in sentinel species exposed to emerging contaminants. |

Protocol: Selecting a Data Mining Method for an Ecotoxicological Problem

Selecting the appropriate data mining technique is a critical step. The following workflow, adapted from the Data Mining Methods Conceptual Map (DMMCM), provides a guided process for method selection [21].

Procedure:

- Define the Problem Objective: Clearly articulate the environmental question. For example, "I want to predict the toxicity of a new chemical" versus "I want to understand the common molecular pathways affected by a class of pesticides" [21].

- Navigate the Decision Tree: Use the workflow above to select a major group of methods.

- If the goal is prediction, use classification (for categories like toxic/non-toxic) or regression (for continuous values like LC50) [19].

- If the goal is knowledge discovery, use clustering to find groups of chemicals with similar effects, or association mining to find frequently co-occurring exposure combinations [19].

- Refine the Method Selection: Consult resources like Data Mining Methods Templates (DMMTs) for detailed guidance on specific algorithms within the chosen branch, considering dataset structure and technical requirements of the methods [21].

Protocol: Data Mining Multi-Omics Data to Derive Transcriptomic Points of Departure

A powerful application of data mining in regulatory ecotoxicology is the derivation of Transcriptomic Points of Departure (tPODs). A tPOD identifies the dose level below which a concerted change in gene expression is not expected in response to a chemical [22]. tPODs provide a pragmatic, mechanistically informed, and health-protective reference dose that can augment or inform traditional apical endpoints from longer-term studies [22].

Experimental Workflow

The following protocol outlines the bioinformatic workflow for tPOD derivation from transcriptomic data.

Step-by-Step Instructions

Study Design and Data Generation:

- Input: Expose model organisms (e.g., fish, rodents) to a range of chemical concentrations, including controls, with a minimum of n=3-5 replicates per group [20].

- Reagent Solution: Extract total RNA from target tissues using commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy). Prepare sequencing libraries with kits like Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA. Perform high-throughput sequencing on platforms like Illumina NovaSeq to generate raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files) [20].

Bioinformatic Processing (Data to Information):

- Quality Control: Use FastQC to assess read quality.

- Read Alignment and Quantification:

- For model species with a reference genome (e.g., zebrafish, rat), align reads using a splice-aware aligner like STAR and generate gene-level counts using featureCounts [20].

- For non-model species, consider a de novo transcriptome assembly using Trinity, or use a species-agnostic tool like Seq2Fun which aligns reads directly to functional ortholog groups, bypassing the need for a reference genome [20].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Input the count matrix into statistical software (e.g., R/Bioconductor) and use packages like

LimmaorEdgeRto identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) for each dose group compared to control. Be aware that different statistical approaches can yield slightly different DEG lists; focus on robust, large-scale patterns [20].

tPOD Derivation (Information to Knowledge):

- Dose-Response Modeling: For the list of DEGs, model the dose-response relationship for each gene individually using specialized software (e.g., BMD Software from the US EPA). Calculate a benchmark dose (BMD) or point of departure for each gene [22].

- Aggregation: Aggregate the gene-level BMDs into a single tPOD. Common practices include taking the median or the 10th percentile of the distribution of gene-level BMDs, which is considered health-protective [22].

- Validation and Interpretation: Compare the derived tPOD with Points of Departure from traditional apical endpoints (e.g., organ weight changes, histopathology). Research strongly supports that tPODs are generally protective of apical outcomes and can be used to anchor a safety assessment [22].

Protocol: Mining the ECOTOX Knowledgebase for Data Gaps

The ECOTOX Knowledgebase is a comprehensive, publicly available resource from the U.S. EPA containing over one million test records on chemical effects for more than 13,000 species [1]. It is a prime resource for data gap analysis via data mining.

Experimental Workflow

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions: Databases and Tools for Ecotoxicology Data Mining

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase [1] | Curated Database | Core source for single-chemical toxicity data for aquatic and terrestrial species. Used for data gap analysis, QSAR model development, and ecological risk assessment. | https://www.epa.gov/comptox-tools/ecotox |

| Seq2Fun [20] | Bioinformatics Algorithm | Species-agnostic tool for analyzing RNA-Seq data from non-model organisms by mapping reads to functional ortholog groups, bypassing the need for a reference genome. | Via ExpressAnalyst |

| BMD Software (US EPA) [22] | Statistical Software Suite | Fits mathematical models to dose-response data to calculate Benchmark Doses (BMDs) for transcriptomic or apical endpoints. | EPA Website |

| Nanoinformatics Approaches [23] | Computational Models & ML | A growing field using QSAR, machine learning, and molecular dynamics to predict nanomaterial behavior and toxicity, addressing a major data gap for engineered nanomaterials. | Various (e.g., Enalos Cloud [23]) |

Step-by-Step Instructions

Define the Scope: Identify the chemical class or family of interest (e.g., "neonicotinoid pesticides") and the relevant taxonomic groups (e.g., "aquatic invertebrates," "pollinators").

Data Acquisition and Mining:

- Access the ECOTOX Knowledgebase [1].

- Use the "SEARCH" feature to query by chemical name or group. Use the "EXPLORE" feature if the exact parameters are not known.

- Apply filters for "Species" (e.g., select "Insecta" class), "Effect" (e.g., "mortality," "reproduction"), and "Exposure Duration."

- Use the "DATA VISUALIZATION" feature to create interactive plots of the results (e.g., species sensitivity distributions).

Data Gap Identification Analysis:

- Quantify Data Richness: For your chemical group of interest, tally the number of test records per species and per endpoint. A high concentration of data on a few standard test species (e.g., Daphnia magna) and a lack of data on threatened or keystone species constitutes a clear data gap.

- Identify Endpoint Gaps: Determine if data is predominantly for acute mortality (LC50) and lacks chronic, sublethal data (e.g., growth, reproduction, immunotoxicity). The latter is often a critical data gap.

- Cross-Reference with New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): Compare the traditional toxicity data with the availability of high-throughput transcriptomic data (e.g., tPODs) for the same chemicals. A lack of mechanistic data represents an opportunity for targeted research using the protocols in Section 3.

Output and Opportunity Prioritization:

- Generate a summary table listing the identified data gaps, ranked by perceived ecological risk and feasibility of testing.

- This analysis directly informs the prioritization of future testing, guiding resource allocation towards filling the most critical knowledge gaps, potentially using faster, more mechanistic NAMs.

The integration of data mining with bioinformatics is fundamentally enhancing how we identify and address research gaps in ecotoxicology. By applying the protocols outlined—from deriving tPODs for mechanistic risk assessment to systematically mining large-scale toxicity databases like ECOTOX—researchers can transition from being data-rich but information-poor to having actionable knowledge and wisdom. These approaches allow for a more proactive, predictive, and efficient research strategy, ultimately accelerating the development of a safer and more sustainable relationship with our chemical environment.

Methodologies in Action: From QSAR to Machine Learning and Omics Integration

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling for Toxicity Prediction

Within the domain of bioinformatics-driven ecotoxicology research, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a pivotal computational methodology for predicting the toxicity of chemicals. QSAR models establish a mathematical relationship between the chemical structure of a compound (represented by molecular descriptors) and its biological activity, such as toxicity [24]. This approach is fundamentally rooted in the principle that the physicochemical properties and biological activities of molecules are determined by their chemical structures [24]. The application of QSAR models enables the rapid, cost-effective hazard assessment of environmental pollutants, which is critical for protecting aquatic biodiversity and human health, aligning with the goals of modern ecotoxicology [25] [18]. The adoption of these non-test methods (NAMs) is further encouraged by international regulations and a global push to reduce reliance on animal testing [26] [16].

Key Concepts and Data Requirements

The foundational equation of a QSAR model can be generalized as: Biological Activity = f(Dâ‚, Dâ‚‚, D₃…) where Dâ‚, Dâ‚‚, D₃, etc., are molecular descriptors that quantitatively encode specific aspects of a compound's structure [24].

The development of a robust and predictive QSAR model is contingent upon a high-quality dataset. The key components of such a dataset are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Essential Components for QSAR Model Development

| Component | Description | Examples & Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structures | The set of compounds under investigation, typically represented in SMILES or SDF format. | Should encompass sufficient structural diversity to ensure model applicability. |

| Biological Activity Data | Experimentally measured toxicity endpoint for each compound. | ICâ‚…â‚€, LDâ‚…â‚€, NOAEL, LOAEL [24] [26]. Values should be obtained via standardized experimental protocols. |

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations of chemical structures. | Physicochemical properties (e.g., log P, molecular weight), topological indices, quantum chemical properties, and 3D-descriptors [24]. |

| Dataset Curation | The process of preparing and verifying the quality of the input data. | Requires removal of duplicates and erroneous structures, and verification of activity data consistency. A typical dataset should contain more than 20 compounds [24]. |

Protocols for QSAR Model Development and Application

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for constructing, validating, and applying a QSAR model for toxicity prediction.

Protocol: Workflow for Robust QSAR Modeling

The process of building a reliable QSAR model follows a structured workflow, from data collection to final deployment. The following diagram illustrates this multi-stage process and the critical steps involved at each stage.

Step 1: Data Collection and Curation

- Action: Compile a dataset of chemical structures and their corresponding experimental toxicity values from public databases (e.g., ToxValDB, ChEMBL, PubChem) [26] [16].

- Protocol Details:

- Standardization: Curate chemical structures by standardizing tautomeric forms, removing counterions, and neutralizing charges.

- Activity Data: Use consistent, comparable activity values (e.g., pICâ‚…â‚€ = -logâ‚â‚€(ICâ‚…â‚€)) obtained from a standardized experimental protocol [24].

- Critical Check: Visually inspect a subset of structures to ensure the correctness of the automated curation.

Step 2: Chemical Structure Representation and Descriptor Calculation

- Action: Convert chemical structures into a numerical format using molecular descriptors.

- Protocol Details:

- Software: Use open-source tools like RDKit or PaDEL-Descriptor to calculate a wide array of descriptors [16].

- Descriptor Types: Calculate 1D descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, log P), 2D descriptors (e.g., topological indices), and 3D descriptors (if optimized 3D structures are available) [24].

- Output: Generate a data matrix where rows are compounds and columns are descriptor values.

Step 3: Dataset Splitting

- Action: Divide the dataset into training and test sets.

- Protocol Details:

- Method: Use a rational splitting method (e.g., Kennard-Stone) or random selection to ensure the test set is representative of the chemical space covered by the training set.

- Ratio: A common practice is to allocate 70-80% of compounds for training and the remaining 20-30% for external testing [24].

Step 4: Feature Selection

- Action: Reduce the number of molecular descriptors to avoid overfitting.

- Protocol Details:

- Methods: Employ techniques like Stepwise Regression, Genetic Algorithms, or the Successive Projections Algorithm [24].

- Goal: Select a small set of 4-6 descriptors that are statistically significant and have low inter-correlation to build a parsimonious model.

Step 5: Model Training

- Action: Establish the mathematical relationship between the selected descriptors and the toxicity endpoint.

- Protocol Details:

- Algorithm Selection:

- Process: Use only the training set to build the model.

Step 6: Model Validation

- Action: Rigorously assess the model's predictive power and robustness. This is a critical step for establishing model credibility.

- Protocol Details:

- Internal Validation: Perform 5-fold or 10-fold cross-validation on the training set. Calculate the cross-validated R² (Q²) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- External Validation: Use the held-out test set to evaluate the model's performance on unseen data. Report R², RMSE, and other relevant metrics.

- Metric Interpretation: For classification models used in virtual screening, prioritize Positive Predictive Value (PPV) to minimize false positives in the top predictions [27].

Step 7: Prediction and Applicability Domain (AD)

- Action: Use the validated model to predict new compounds while defining its limitations.

- Protocol Details:

- Prediction: Input the descriptor values of the new compound into the model equation to obtain a predicted toxicity value.

- Applicability Domain: Define the chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable. Methods include the leverage approach, which identifies whether a new compound is structurally extreme compared to the training set [24]. Predictions for compounds outside the AD should be treated with caution.

Protocol: Virtual Screening for Hit Identification

When using a QSAR model to screen large chemical libraries, a specific protocol should be followed to maximize the identification of true toxicants or active compounds.

- Step 1: Load a large, commercially available chemical library (e.g., Enamine REAL).

- Step 2: Process all compounds through the previously developed and validated QSAR model.

- Step 3: Rank all compounds based on their predicted activity/toxicity score.

- Step 4: For experimental testing, select the top N compounds (e.g., 128 for a standard well plate) from the ranked list. This strategy prioritizes the Positive Predictive Value (PPV) of the model for the top-ranked compounds, ensuring a higher hit rate and minimizing false positives [27].

- Step 5: Acquire and test the selected compounds experimentally to confirm the model's predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The successful application of QSAR in ecotoxicology relies on a suite of software, databases, and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| OECD QSAR Toolbox [28] | Software Platform | Streamlines chemical hazard assessment by profiling chemicals, simulating metabolism, finding analogues, and filling data gaps via read-across. |

| RDKit [16] | Cheminformatics Library | Open-source toolkit for calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprinting, and handling chemical data. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints for batch processing of chemical structures. |

| ToxValDB [26] | Database | A comprehensive database of experimental in vivo toxicity values used for model training and validation. |

| ChEMBL [27] | Database | A large-scale bioactivity database for drug-like molecules, useful for building models related to specific targets. |

| Random Forest [25] [26] | Algorithm | A powerful machine learning algorithm frequently used for building high-performance classification and regression QSAR models. |

| 6-phospho-2-dehydro-D-gluconate(1-) | 6-phospho-2-dehydro-D-gluconate(1-) Research Chemical | High-purity 6-phospho-2-dehydro-D-gluconate(1-) for research. Key intermediate in the pentose phosphate pathway. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Garcinone B | Garcinone B, CAS:76996-28-6, MF:C23H22O6, MW:394.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Case Study: Predicting NF-κB Inhibitor Toxicity

To illustrate the protocol, consider a case study developing a QSAR model for 121 compounds reported as Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibitors [24].

- Data Preparation: ICâ‚…â‚€ values were converted to pICâ‚…â‚€. The dataset was randomly split into a training set (~80 compounds) and a test set (~41 compounds).

- Descriptor Calculation & Selection: A pool of molecular descriptors was calculated. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to identify descriptors with high statistical significance for predicting NF-κB inhibitory concentration [24].

- Model Training & Validation: Two models were developed and compared:

- A Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) model.

- An Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model.

- Both models underwent rigorous internal and external validation. The leverage method was applied to define the Applicability Domain [24].

Table 3: Performance Metrics for the NF-κB Inhibitor QSAR Models

| Model Type | Training Set R² | Internal Validation Q² | Test Set R² | RMSE (Test Set) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | Reported in study | Reported in study | Reported in study | Reported in study |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Reported in study | Reported in study | Reported in study | Reported in study |

Note: Specific metric values from the original study should be inserted into the table above [24].

{# The Application of Machine Learning and the ADORE Benchmark Dataset for Predicting Aquatic Toxicity}

{#brief_paragraph}

The increasing production and release of chemicals into the environment necessitates robust methods for assessing their potential hazards to aquatic ecosystems. While traditional ecotoxicology relies on animal testing, in silico methods, particularly machine learning (ML), offer promising alternatives for predicting chemical toxicity. The development of the ADORE (A benchmark dataset for machine learning in ecotoxicology) dataset addresses a critical bottleneck by providing a standardized, well-curated resource for training, benchmarking, and comparing ML models. This application note details the implementation of ML workflows with ADORE, providing protocols and resources to advance computational ecotoxicology within a bioinformatics framework.

{#dataset_overview}

ADORE Dataset: Composition and Scope

The ADORE dataset is a comprehensive resource designed to foster machine learning applications in ecotoxicology. It integrates ecotoxicological experimental data with extensive chemical and species-specific information, enabling the development of models that can predict acute aquatic toxicity.

Table 1: Core Components of the ADORE Dataset

| Component | Description | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Ecotoxicology Data | Core data on acute mortality and related endpoints (LC50/EC50) for fish, crustaceans, and algae, including experimental conditions [17]. | US EPA ECOTOX database (September 2022 release) [17]. |

| Chemical Information | Nearly 2,000 chemicals represented by identifiers (CAS, DTXSID, InChIKey), canonical SMILES, and six molecular representations (e.g., MACCS, PubChem, Morgan fingerprints, Mordred descriptors) [17] [29]. | PubChem, US EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [17]. |

| Species Information | 140 fish, crustacean, and algae species, with data on ecology, life history, and phylogenetic relationships [17] [30]. | ECOTOX database and curated phylogenetic trees [17]. |

Table 2: Dataset Statistics and Proposed Modeling Challenges

| Taxonomic Group | Key Endpoints | Standard Test Duration | Modeling Challenge Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | Mortality (MOR), LC50 [17] | 96 hours [17] | High (All groups), Intermediate (Single group), Low (Single species) [29] |

| Crustaceans | Mortality (MOR), Immobilization/Intoxication (ITX), EC50 [17] | 48 hours [17] | High (All groups), Intermediate (Single group), Low (Single species) [29] |

| Algae | Mortality (MOR), Growth (GRO), Population (POP), Physiology (PHY), EC50 [17] | 72 hours [17] | High (All groups), Intermediate (Single group) [29] |

The dataset is structured around specific modeling challenges of varying complexity, from predicting toxicity for single, well-represented species like Oncorhynchus mykiss (rainbow trout) and Daphnia magna (water flea), to extrapolating across all three taxonomic groups [29].

{#protocol1}

Protocol 1: Implementing a QSAR Workflow for Acute Toxicity Prediction

This protocol outlines the use of the OECD QSAR Toolbox, a widely used software for predicting chemical toxicity, to assess the acute aquatic toxicity of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) [31]. The workflow can be adapted for other chemical classes.

Materials and Software

- OECD QSAR Toolbox Software: Freely available application for chemical hazard assessment [31].

- Chemical List: Target substances identified by their Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) numbers or SMILES codes [31].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Input Target Substances: Launch the QSAR Toolbox. In the "Input" module, enter the CAS numbers or SMILES codes of the target substances. For batch processing, create and upload a text file listing one CAS number per row [31].

- Profiling: Navigate to the "Profiling" module. Select relevant profilers, particularly those under "Endpoint Specific" related to aquatic toxicity (e.g., ecotoxicological hazard). Apply the profilers to categorize the chemicals [31].

- Data Collection: Go to the "Data" module. Use the "Gather" function to collect experimental data for the endpoints of interest, such as "Fish, lethal concentration 50% at 96 hours." The data can be exported as a matrix for external analysis [31].

- Data Gap Filling (Prediction): In the "Data Gap Filling" module, select the "Automated" workflow. Choose the desired endpoint (e.g., "Fish, LC50 at 96h") and execute the prediction. The Toolbox will use its internal databases and models to fill data gaps for the target chemicals [31].

- Report Generation: Finally, use the "Report" module to generate a customized report. Save the prediction results, including the calculated LC50 values and any confidence intervals, as PDF and spreadsheet files [31].

Data Interpretation

The predicted LC50 values should be compared to experimental data, if available, to validate the model. A positive correlation between predicted and experimental values on a log-log scale indicates a reliable model [31]. For a conservative safety assessment, the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval of the predicted LC50 can be used as a protective threshold [31].

{#protocol2}

Protocol 2: Building an ML Model with the ADORE Dataset

This protocol describes the process of developing a machine learning model using the ADORE dataset, focusing on the critical step of data splitting to avoid over-optimistic performance estimates.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for ADORE-based ML Research

| Tool Category | Example(s) | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representations | MACCS, PubChem, Morgan fingerprints, Mordred descriptors, mol2vec [29] | Translate chemical structures into a numerical format interpretable by ML algorithms. |

| Phylogenetic Information | Phylogenetic distance matrices [17] [29] | Encodes evolutionary relationships between species, potentially informing cross-species sensitivity. |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Provide algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Neural Networks) for building regression or classification models. |

| Bioinformatics Packages | DRomics R package [3] | Assists in dose-response modeling of omics data, which can be integrated with apical endpoint data. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Preprocessing: Access the ADORE dataset. Handle missing values appropriately (e.g., imputation or removal). For regression tasks, the target variable is typically the log-transformed LC50/EC50 value.

- Feature Selection and Engineering: Select from the available chemical (e.g., molecular fingerprints) and biological features (e.g., species phylogenetic group, life history traits). Feature scaling may be applied.

- Critical Step: Data Splitting: Implement a splitting strategy that prevents data leakage. A random split is insufficient due to repeated experiments for the same chemical-species pair.

- Scaffold Split: Ensure that chemicals in the test set are structurally distinct (based on molecular scaffolds) from those in the training set [17] [29].

- Stratified Split: Maintain the distribution of taxonomic groups or specific endpoints across training and test sets.

- ADORE provides predefined splits to ensure comparability across studies [17] [30].

- Model Training and Validation: Train the chosen ML model (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) on the training set. Use cross-validation on the training set to tune hyperparameters.

- Model Evaluation: Finally, evaluate the final model's performance on the held-out test set using metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R² for regression tasks.

{#advanced_applications}

Advanced Applications and Integration with Omics Data

Beyond QSAR and basic ML, the field of ecotoxicology is leveraging more complex bioinformatics approaches. The ADORE framework provides a foundation for integrating diverse data types, including high-throughput omics data.

Transcriptomic Points of Departure (tPOD): tPODs are derived from dose-response transcriptomics data and identify the dose level below which no concerted change in gene expression is expected [22]. They offer a sensitive, mechanism-based, and animal-sparing alternative to traditional toxicity thresholds. Bioinformatic workflows for tPOD derivation, often implemented in R packages like

DRomics[3], are being standardized for regulatory application [22]. Studies have shown that tPODs from zebrafish embryos are often more sensitive or align well with chronic toxicity values from longer-term fish tests [3].Multi-Omics Integration: Combining multiple omics layers (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) provides a systems-level view of toxicity mechanisms. For instance, a study on zebrafish exposed to Aroclor 1254 linked transcriptomic changes in visual function genes with metabolomic shifts in neurotransmitter-related metabolites, offering a comprehensive biomarker profile [3]. Machine learning is crucial for integrating these complex, high-dimensional datasets.

{#conclusion}

The ADORE dataset establishes a critical benchmark for developing and validating machine learning models in ecotoxicology. By providing standardized data on chemical properties, species sensitivity, and ecotoxicological outcomes, it enables reproducible and comparable research. The protocols outlined for QSAR analysis and ML model building, with an emphasis on proper data splitting, provide a clear roadmap for researchers. The integration of these computational approaches with emerging omics technologies, such as tPOD derivation, represents the future of bioinformatics in ecotoxicology, promising more efficient, mechanism-based, and predictive chemical safety assessment.

Toxicogenomics represents a powerful bioinformatics-driven approach that integrates gene expression profiling with traditional toxicology to elucidate the mechanisms by which chemicals induce adverse effects. This methodology is particularly valuable in ecotoxicology research, where understanding the molecular initiating events of toxicity can lead to more accurate hazard assessments for environmental contaminants. By analyzing genome-wide transcriptional changes, researchers can identify * conserved pathway alterations* and chemical-specific signatures that precede morphological damage, providing early indicators of toxicity and revealing novel insights into modes of action [32]. The application of toxicogenomics within a bioinformatics framework enables a systems-level understanding of chemical-biological interactions, moving beyond traditional endpoint observations to capture the complex network of molecular events that underlie toxic responses in environmentally relevant species.

Application in Ecotoxicology: A Case Study on Agrichemicals

Experimental Design and Workflow

To illustrate the practical application of toxicogenomics in ecotoxicology, we examine a recent study that investigated the effects of diverse agrichemicals on developing zebrafish. This research employed a phenotypically anchored transcriptomics approach, systematically linking morphological outcomes to gene expression changes [32]. The experimental workflow encompassed several critical stages from chemical selection to data integration, providing a comprehensive framework for mechanism elucidation.

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters for Zebrafish Toxicogenomics Study

| Experimental Component | Specifications | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Organism | Tropical 5D wild-type zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Model vertebrate with high genetic homology to humans |

| Exposure Window | 6 hours post-fertilization (hpf) to 120 hpf | Captures key developmental processes |

| Transcriptomic Sampling | 48 hpf | Identifies early molecular events prior to morphological manifestations |

| Chemical Diversity | 45 agrichemicals from EPA ToxCast library | Represents real-world environmental exposures |

| Concentration Range | 0.25 to 100 µM | Establishes concentration-response relationships |

| Morphological Endpoints | Yolk sac edema, craniofacial malformations, axis abnormalities | Provides phenotypic anchoring for transcriptomic data |

The experimental design prioritized temporal sequencing of molecular and phenotypic events, with transcriptomic profiling conducted at 48 hpf—before the appearance of overt morphological effects at 120 hpf. This approach enables distinction between primary transcriptional responses and secondary compensatory mechanisms, offering clearer insight into molecular initiating events [32].

Computational and Bioinformatics Analysis

The bioinformatics workflow for toxicogenomics data analysis involves multiple processing steps and analytical techniques to extract biologically meaningful information from raw sequencing data.

Table 2: Transcriptomic Data Analysis Methods

| Analytical Method | Application | Software/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression Analysis | Identification of significantly altered genes | DESeq2, EdgeR, Limma-Voom |

| Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment | Functional interpretation of gene lists | ClusterProfiler, TopGO |

| Co-expression Network Analysis | Identification of coordinately regulated gene modules | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) |

| Semantic Similarity Analysis | Comparison of GO term enrichment across treatments | GOSemSim |

| Pathway Analysis | Mapping gene expression changes to biological pathways | KEGG, Reactome, MetaCore |

The study identified between 0 and 4,538 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) per chemical, with no clear correlation between the number of DEGs and the severity of morphological outcomes. This finding underscores that transcriptomic sensitivity often exceeds morphological assessments and that different chemicals can elicit distinct molecular responses even at similar phenotypic severity levels [32]. Both DEG and co-expression network analyses revealed chemical-specific expression patterns that converged on shared biological pathways, including neurodevelopment and cytoskeletal organization, highlighting how structurally diverse compounds can disrupt common physiological processes.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Zebrafish Husbandry and Exposure Protocol

Purpose: To maintain consistent zebrafish breeding populations and perform controlled chemical exposures for developmental toxicogenomics studies.

Materials:

- Tropical 5D wild-type zebrafish breeding colonies

- Embryo medium (EM): 15 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM KCL, 1 mM MgSO₄, 0.15 mM KH₂PO₄, 0.05 mM Na₂HPO₄, 0.7 mM NaHCO₃

- 96-well U-bottom plates (Falcon, Product no. 353227)

- Pronase solution for dechorionation

- HP D300 digital dispenser for precise chemical dosing

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as vehicle solvent

Procedure:

- Maintain zebrafish at 28°C under 14:10 h light/dark cycle in recirculating system water supplemented with Instant Ocean salts.

- Collect embryos between 8:00-9:00 a.m. using spawning funnels placed in tanks the night before.

- Select only fertilized embryos of high quality and matched developmental stage at 4 hours post-fertilization (hpf).

- Enzymatically dechorionate embryos using pronase solution to ensure consistent chemical exposure.

- Singulate dechorionated embryos into 96-well plates containing 100 µL embryo medium using robotic placement systems.

- At 6 hpf, dispense test chemicals using digital dispenser to achieve target nominal concentrations while maintaining 0.5% DMSO concentration across all exposures.

- Conduct static exposures from 6 to 120 hpf, with solution renewal at 48 hpf for extended exposures.

- For transcriptomic analysis, sample larvae at 48 hpf by rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen.

- For morphological assessment, evaluate specimens at 120 hpf across multiple endpoints including yolk sac edema, craniofacial malformations, and axis abnormalities [32].

Quality Control:

- Include vehicle controls (0.5% DMSO) and negative controls in all experiments

- Perform range-finding assays to determine appropriate concentration ranges

- Use randomized plate designs to control for positional effects

- Conduct blind scoring of morphological endpoints to minimize bias

RNA Sequencing and Transcriptomic Profiling Protocol

Purpose: To generate high-quality transcriptomic data from zebrafish embryos for differential gene expression analysis.

Materials:

- TRIzol reagent or equivalent for RNA isolation

- DNase I treatment kit

- RNA integrity measurement system (e.g., Bioanalyzer)

- Library preparation kit for Illumina sequencing

- Sequencing platforms (Illumina NovaSeq, HiSeq, or NextSeq)

- Bioinformatics computational infrastructure

Procedure:

- Homogenize pooled zebrafish samples (n=15-30 embryos per condition) in TRIzol reagent.