Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOP): A Transformative Framework for 21st Century Toxicology and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework, a conceptual tool designed to organize mechanistic biological data for predicting chemical hazards.

Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOP): A Transformative Framework for 21st Century Toxicology and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework, a conceptual tool designed to organize mechanistic biological data for predicting chemical hazards. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of AOPs, detailing their modular structure centered on Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs), Key Events (KEs), and Adverse Outcomes (AOs). The article delves into methodological advances, including the development of quantitative AOP (qAOP) models using systems toxicology and Bayesian networks, and illustrates their application in replacing animal testing and prioritizing endocrine-disrupting chemicals. It further addresses troubleshooting through international harmonization initiatives like the OECD Coaching Program and validates the framework's utility via case studies and comparative analysis with traditional risk assessment models. The synthesis aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage AOPs for enhancing predictive toxicology and regulatory decision-making.

Deconstructing the AOP Framework: From Biological Dominos to Chemical-Agnostic Pathways

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework is a conceptual construct that organizes existing knowledge about biologically plausible and empirically supported links between a direct molecular perturbation and an adverse outcome of regulatory relevance [1]. It provides a standardized structure for describing sequential chains of causally linked events across different levels of biological organization that occur following exposure to a chemical or non-chemical stressor [2] [3]. The AOP framework serves as a translational tool that enhances communication between scientists who generate toxicity data and the risk assessors or regulators who use this information for decision-making [2]. By offering a structured approach to understanding toxicity pathways, AOPs support the use of different types of biological data to complement or potentially replace traditional in vivo animal studies, aligning with the 3Rs (refinement, reduction, and replacement) agenda in toxicology [4].

The fundamental structure of an AOP follows a linear sequence of events, typically starting with a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) and progressing through measurable Key Events (KEs) at increasing levels of biological organization until an Adverse Outcome (AO) is reached [2] [1]. This conceptual framework has gained significant international traction through organizations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which maintains an AOP Knowledge Base and oversees a formal AOP development program [3]. The utility of AOPs extends to both human health and ecological risk assessment, with particular value in prioritizing chemicals for further testing, building confidence in New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), and addressing the challenge of assessing thousands of data-poor chemicals in the environment [2] [5].

Core Components of an Adverse Outcome Pathway

Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs)

A Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) is defined as the initial interaction between a molecule (stressor) and a biomolecule or biosystem that can be causally linked to an outcome via a pathway [6]. It represents the point where a chemical directly interacts with a biological target within an organism to create a perturbation that starts the AOP [1]. By definition, the MIE occurs at the molecular level and anchors the "upstream" end of an AOP [1]. The MIE is the first biological "domino" in the sequence, triggering the cascade of events that follows [2].

MIEs can take various forms depending on the specific stressor and biological target involved. Common examples include:

- Chemical binding to specific receptors (e.g., estrogen receptor) [2]

- Inhibition of enzymes (e.g., acetylcholinesterase inhibition) [7]

- Direct chemical binding to DNA [2] [5]

- Generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8]

- Inhibition of mitochondrial complex I [7]

A critical characteristic of MIEs is that they are not stressor-specific. Different chemicals or stressors can trigger the same MIE if they interact with the same biological target, and a single stressor might initiate multiple MIEs [2]. The precise definition and characterization of MIEs enable researchers to use a combination of biological and chemical approaches to identify and characterize these initial events, even for some of the most studied molecules in toxicology [6].

Key Events (KEs) and Key Event Relationships (KERs)

Key Events (KEs) represent measurable biological changes at different levels of biological organization that occur after a Molecular Initiating Event and before an Adverse Outcome [2] [5]. These events are essential, but not necessarily sufficient, for the progression from a defined biological perturbation toward a specific adverse outcome [1]. KEs provide verifiability to an AOP description and are represented as nodes in AOP diagrams or networks [1].

KEs occur at increasing levels of biological complexity, spanning from molecular and cellular levels to tissue, organ, and organism levels [2]. The sequence of KEs represents the progression of toxicity through biological systems, with each event causally linked to the next. Key Event Relationships (KERs) describe the scientifically-based connections between pairs of KEs, identifying one as upstream and the other as downstream [2] [1]. KERs facilitate inference or extrapolation of the state of a downstream KE from the known, measured, or predicted state of an upstream KE [1].

KERs are defined based on three types of evidence [2]:

- Biological plausibility - existing biological knowledge supports the relationship

- Empirical support - experimental evidence demonstrates that one KE causes another

- Quantitative understanding - knowledge of the conditions (timing, magnitude, duration) under which a change in one KE will cause a change in another

Adverse Outcomes (AOs)

An Adverse Outcome (AO) is a specialized type of key event measured at a level of organization that corresponds with an established protection goal and/or is functionally equivalent to an apical endpoint measured as part of an accepted guideline test [1]. AOs typically occur at the organ level or higher and anchor the "downstream" end of an AOP [1]. They represent biological changes considered relevant for risk assessment and regulatory decision-making, such as impacts on human health and well-being or effects on survival, growth, or reproduction in wildlife [2] [5].

Table 1: Characteristics of Core AOP Components

| Component | Definition | Level of Biological Organization | Role in AOP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) | Initial interaction between a stressor and a biomolecule that starts the AOP [6] [1] | Molecular | Anchors the upstream end of the AOP; the first "domino" in the sequence [2] |

| Key Event (KE) | Measurable biological change that is essential for progression toward the AO [2] [1] | Cellular, Tissue, Organ | Intermediate steps that verify progression along the pathway; nodes in AOP diagrams [1] |

| Adverse Outcome (AO) | Biological change relevant for risk assessment/regulatory decision making [2] [5] | Organ, Organism, Population | Anchors the downstream end of the AOP; represents the toxicological endpoint of concern [1] |

AOs are distinguished from other KEs by their direct relevance to regulatory protection goals. Examples include tumor formation, learning and memory impairment, reproductive dysfunction, population-level effects such as disrupted sex ratios in fish populations, and early life stage mortality [2] [7]. The identification of AOs is crucial for contextualizing the practical significance of the pathway and determining its applicability to risk assessment.

The AOP Conceptual Framework: Linking MIEs to AOs

The AOP framework conceptually links MIEs to AOs through a sequential series of KEs connected by KERs, creating a chain of events that spans multiple biological organizational levels [2]. This construct has been likened to a series of "biological dominos," where the initial interaction (MIE) triggers a cascade of biological changes (KEs) that ultimately lead to the adverse health effect (AO) [2] [5]. If any KE in the sequence does not occur (i.e., a domino does not fall), then none of the downstream KEs in the pathway will occur [2].

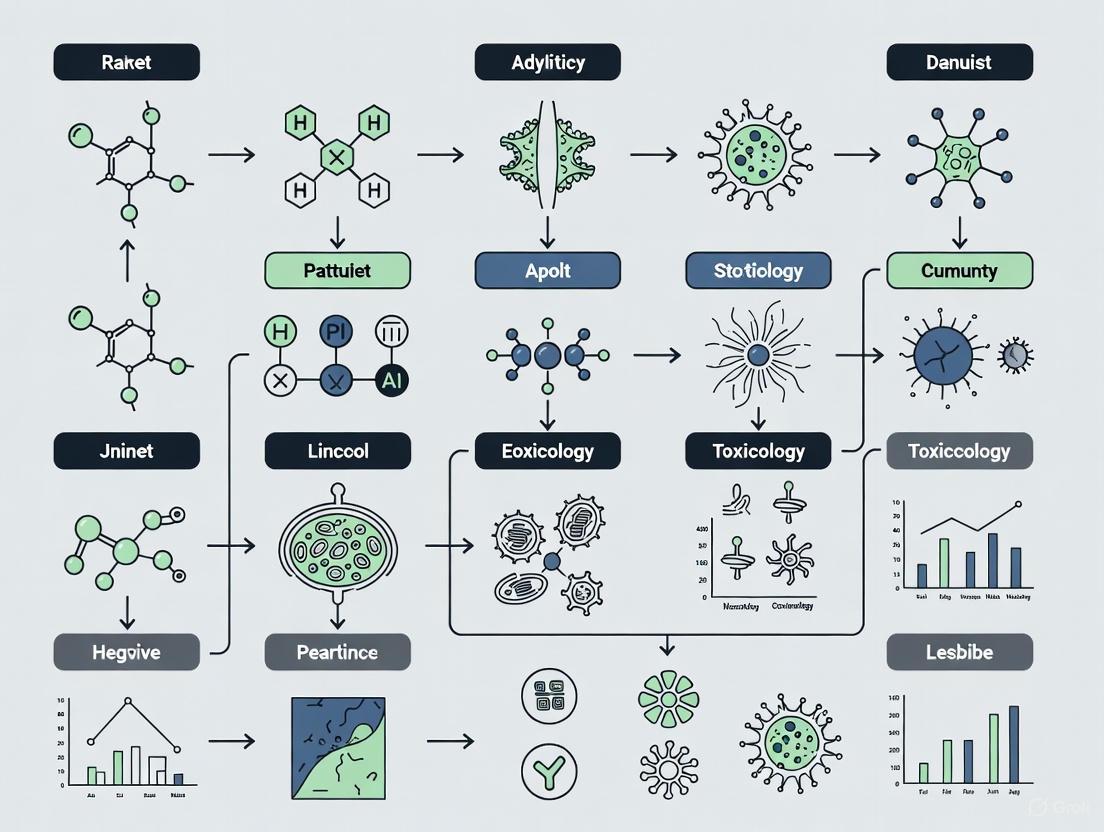

The following diagram illustrates the linear progression of an AOP from Molecular Initiating Event to Adverse Outcome:

A key principle of the AOP framework is that AOPs are not stressor-specific [2]. They depict generalized sequences of biological effects that can be expected for any stressor that directly changes a particular biological target defined by the MIE. For example, several different chemicals could all trigger the same MIE and subsequently follow the same AOP [2]. This principle enhances the predictive utility of AOPs by allowing knowledge gained from one chemical to be applied to others that share the same MIE.

Another important characteristic is that AOPs are modular, meaning any AOP can be represented as a sequence of "nodes" (KEs) and "edges" (KERs) linking those KEs together [2]. This modularity allows for the assembly of AOP networks when multiple AOPs share common KEs and/or KERs [2]. These AOP networks more accurately capture the complexity of real biological systems and become more complete as more AOPs are defined [2]. The following diagram illustrates how multiple AOPs can form an interconnected network:

AOPs are considered "living documents" that can be continually expanded or refined as new evidence emerges and new methods for measuring KEs become available [2]. This dynamic nature allows the AOP framework to incorporate advancing scientific knowledge and technological capabilities, enhancing its utility for chemical safety assessment over time.

Quantitative AOPs: From Qualitative to Quantitative Applications

While qualitative AOPs provide valuable conceptual frameworks, there is a growing need for quantitative AOPs (qAOPs) to support chemical risk assessment [7]. A qAOP incorporates mathematical representations of the Key Event Relationships, enabling prediction of the magnitude of biological changes needed before an adverse outcome is observed [7] [4]. The development of qAOPs represents a significant advancement in the field, as it allows for more precise extrapolation from in vitro data to in vivo outcomes and supports quantitative risk assessment [4].

Several mathematical approaches have been employed to develop qAOPs [7] [4]:

- Response-response relationships - Fitting functions to key event data bounding one or more KERs

- Biologically based mathematical modeling - Using ordinary differential equations to represent biological processes (systems biology modeling)

- Bayesian Network modeling - Implementing causal modeling approaches using Bayesian Networks, particularly useful for complex AOPs with multiple pathways

The transition from qualitative to quantitative AOPs faces several challenges, including the availability of quantitative data amenable to model development, the lack of studies that measure multiple key events simultaneously, and issues with model accessibility and transferability across platforms [7]. However, recent proof-of-concept studies have demonstrated the feasibility of qAOP modeling for complex scenarios, including chronic toxicity from repeated exposures [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Qualitative and Quantitative AOPs

| Characteristic | Qualitative AOP | Quantitative AOP (qAOP) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Organize knowledge; conceptual understanding of toxicity pathways [7] | Predict outcomes; support risk assessment decisions [7] [4] |

| KER Description | Qualitative based on biological plausibility [2] | Mathematical relationships between KEs [7] |

| Data Requirements | Empirical evidence of causal links [2] | Quantitative data on dose-response and timing [7] |

| Regulatory Application | Hypothesis generation; chemical prioritization [2] | Prediction of point-of-departure; extrapolation to human relevant exposures [4] |

| Temporal Component | Not explicitly included [4] | Can incorporate time (e.g., Dynamic Bayesian Networks) [4] |

qAOP development logically follows qualitative AOP development, building upon the established causal relationships to create predictive models [7]. The utility of qAOPs is particularly evident in their ability to reduce the time and resources spent on chemical toxicity testing while improving the extrapolation of data collected at the molecular level to predict whether an adverse outcome may occur at the organism level [7]. As the field advances, qAOPs are expected to play an increasingly important role in regulatory decision-making, especially with the growing use of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that generate in vitro and in silico data [4].

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Establishing Key Event Relationships

The development of robust AOPs requires rigorous experimental approaches to establish and validate Key Event Relationships. The OECD Guidance Document on Developing and Assessing Adverse Outcome Pathways provides a structured framework for building scientific confidence in AOPs through modified Bradford-Hill criteria [3] [7]. The weight of evidence (WoE) evaluation for KERs is based on three fundamental considerations: biological plausibility, empirical support, and quantitative understanding [2] [7].

Biological plausibility depends on established scientific knowledge about the biological relationship between events, including consistent mechanistic data from multiple studies [2]. Empirical support requires demonstration that altering the upstream key event consistently and predictably affects the downstream key event across multiple studies, preferably from different laboratories [2]. Quantitative understanding involves characterizing the conditions (dose-response, timing, magnitude) under which a change in one KE will cause a change in another KE [2].

Experimental approaches for establishing KERs include:

- In vitro assays that measure specific molecular and cellular responses

- In vivo studies using surrogate species to validate pathway conservation

- Cross-species extrapolation using tools like EPA's SeqAPASS to evaluate conservation of pathways across species [2]

- Multi-endpoint studies that measure multiple key events simultaneously to establish temporal and dose-response relationships [7]

Case Study: AChE Inhibition Leading to Neurodegeneration

A specific case study of AOP development for acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition leading to neurodegeneration (AOP 281) illustrates the experimental approaches used in AOP construction [7]. This AOP begins with the Molecular Initiating Event of AChE inhibition, which results in an excess of acetylcholine in the synapse (KER 1) [7]. The build-up of acetylcholine overactivates muscarinic acetylcholine receptors within the brain (KER 2), initiating local seizures (KER 3) [7]. Spreading of the focal seizure through glutamate release (KER 4) and subsequent activation of NMDA receptors (KER 5) propagates the excitotoxicity and leads to elevated intracellular calcium levels (KER 6), status epilepticus (KER 7), and ultimately cell death (KER 8) and neurodegeneration (KER 9) [7].

The quantitative development of this AOP involved a comprehensive literature review encompassing over 200 papers, with data gathered and grouped into two categories: model development and model evaluation [7]. Ideally, model development data covers at least two adjacent key events, allowing for the establishment of quantitative relationships between them [7]. This case study highlights both the methodological approaches and the challenges in developing quantitative AOPs, particularly the need for data that spans multiple key events and the integration of diverse data types into coherent mathematical models.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Resources for AOP Development

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in AOP Research |

|---|---|---|

| AOP Wiki | Primary platform for AOP development and dissemination [2] [3] | Crowdsourced AOP development; qualitative organization of AOP knowledge [2] [3] |

| AOP Knowledge Base | Suite of web-based tools for AOP information [3] | Central repository for AOP-related data; searchable database of AOPs [5] [3] |

| SeqAPASS Tool | Evaluate protein sequence similarity across species [2] | Cross-species extrapolation; assessment of pathway conservation [2] |

| Bayesian Network Analysis | Mathematical framework for causal modeling [7] [4] | Quantitative AOP development; prediction of adverse outcomes [7] [4] |

| In Vitro NAMs | New Approach Methodologies using cell-based systems [5] [4] | Generate data for key events; reduce animal testing [5] [4] |

The experimental workflow for AOP development typically begins with the identification of a well-established Adverse Outcome and works backward to identify preceding Key Events and the Molecular Initiating Event [1]. Alternatively, AOP development can begin with a well-characterized MIE and work forward to identify subsequent KEs and potential AOs [1]. In both approaches, the emphasis is on establishing causal relationships supported by robust experimental evidence rather than mere correlative associations.

Applications in Toxicology and Risk Assessment

The AOP framework has diverse applications in toxicology and risk assessment, significantly enhancing how scientists evaluate potential chemical hazards and assess risks. One of the most valuable applications is the enhanced use of data from New Approach Methods (NAMs) [2]. When traditional in vivo animal study data are lacking for a chemical, in vitro experiments can provide insights into the chemical's hazard potential if there is an AOP that links the in vitro data to an adverse outcome [2]. For example, if a chemical causes a specific DNA mutation in an in vitro screening assay and that mutation is the MIE in an AOP for liver cancer, the AOP information can be used as one tool to assess whether the chemical is a potential carcinogen [2].

Additional applications include [2]:

- Hypothesis-driven testing - Knowledge of health effects likely to follow a given MIE can help focus in vivo testing on sensitive species, life-stages, and toxicity endpoints

- Cross-species extrapolation - Using AOP knowledge to directly evaluate conservation of pathways and quantitative differences in toxicological response across species

- Evaluation of complex mixtures - Using insights from AOP networks to address uncertainties associated with prediction of mixture effects

- Chemical prioritization - Helping to narrow down the list of chemicals for subsequent testing when traditional toxicity data are lacking

The AOP framework also supports mode of action (MOA) analysis, which describes a biologically plausible sequence of key events leading to an observed effect supported by robust experimental observations and mechanistic data [1]. While AOPs and MOAs are related concepts, they are not synonymous. An MOA usually starts with the molecular initiating event but does not typically include consideration of exposure or effects at higher levels than the individual, whereas AOPs explicitly include these elements [1].

The framework is particularly valuable for addressing priority toxicological endpoints such as endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity, and immunotoxicity [5]. For example, EPA researchers are using AOPs to investigate key events underlying thyroid hormone-dependent developmental neurotoxicity and the effects of inhaled reactive gases on cells of the respiratory tract leading to inflammation, abnormal cell growth, and asthma [5]. Similarly, AOPs relevant to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are being developed to evaluate a wide range of adverse outcomes, including reproductive impairment, developmental toxicity, metabolic disorders, kidney toxicity, and cardiac toxicity [5].

The Adverse Outcome Pathway framework provides a systematic approach for organizing knowledge about the sequence of events linking molecular initiating events to adverse outcomes of regulatory concern. The core concepts of MIEs, KEs, and AOs form the foundational elements of this framework, enabling a structured understanding of toxicity pathways across multiple levels of biological organization. As a conceptual tool, the AOP framework enhances the interpretation of mechanistic data and supports more informed chemical safety assessment.

The transition from qualitative to quantitative AOPs represents the next frontier in AOP research, with promising developments in mathematical modeling approaches such as Bayesian Network analysis [7] [4]. These quantitative applications have the potential to transform chemical risk assessment by enabling predictions of adverse outcomes based on upstream key events measured using in vitro or in silico methods. However, challenges remain in data availability, model development, and establishing scientific confidence in quantitative predictions.

As the AOP knowledge base continues to expand through international collaborative efforts, the framework is poised to play an increasingly important role in regulatory decision-making. The "living document" nature of AOPs allows for continuous refinement as new scientific evidence emerges, ensuring that the framework remains relevant and responsive to advancing toxicological science. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core concepts and their applications provides a valuable foundation for leveraging the AOP framework in chemical safety assessment and therapeutic development.

Within the framework of Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs), the concept of a 'Biological Domino' effect provides a powerful mechanistic model for understanding toxicity. An AOP describes a sequence of events commencing with the initial interaction of a stressor with a biomolecule within an organism, a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE), which can progress through a dependent series of intermediate Key Events (KEs) and culminates in an Adverse Outcome (AO) considered relevant to risk assessment [5] [9]. Key Event Relationships (KERs) are the scientifically grounded causal linkages that connect these individual key events, forming the backbone of the AOP and enabling predictive toxicology [9]. This conceptual domino effect is not merely a linear cascade but a structured representation of biological causality, where the relationship between an upstream and downstream event is both definable and measurable [10]. The AOP framework is intentionally chemical-agnostic, focusing on the biological progression of events rather than the properties of any specific chemical, thereby allowing for broad application across various stressors [10].

The Conceptual Foundation: KERs as Biological Dominos

The Domino Analogy in Biology and Toxicology

The domino effect serves as an apt analogy for AOPs. Just as a single falling domino can trigger a chain reaction, the molecular initiating event sets off a cascade of biological changes [5]. The EPA describes this succinctly: "A chemical exposure leads to a biological change within a cell and then a 'molecular initiating event' (e.g., chemical binding to DNA) triggers more dominos to fall in a cascade of sequential 'key events' (e.g., abnormal cell replication) along a toxicity pathway. Together, these events can result in an adverse health outcome... in a whole organism" [5]. This analogy extends to neurobiology, where falling dominoes have been used to model the all-or-nothing, unidirectional propagation of a nerve impulse—a characteristic shared by the key event relationships in an AOP [11]. In both systems, a stimulus must exceed a critical threshold to initiate the cascade, the pulse moves at a constant speed without losing energy, and the system requires energy to reset [11].

Core Definitions and Modularity Principle

The functional components of an AOP are built upon precise definitions and a modular structure:

- Molecular Initiating Event (MIE): A specialized type of key event that represents the initial point of chemical/stressor interaction at the molecular level within the organism that results in a perturbation that starts the AOP [9].

- Key Event (KE): A measurable biological change at the molecular, cellular, or tissue level that occurs after a molecular initiating event and before an adverse outcome. A KE is a change in biological or physiological state that is both measurable and essential to the progression of a defined biological perturbation leading to a specific adverse outcome [5] [9].

- Key Event Relationship (KER): A scientifically-based relationship that connects one key event to another, defines a causal and predictive relationship between the upstream and downstream event, and thereby facilitates inference or extrapolation of the state of the downstream key event from the known, measured, or predicted state of the upstream key event [9].

- Adverse Outcome (AO): A specialized type of key event that is generally accepted as being of regulatory significance on the basis of correspondence to an established protection goal [9].

A fundamental principle in AOP development is modularity. KEs and KERs are constructed as discrete, self-contained units that can be reused in multiple AOPs, enhancing consistency and efficiency [9] [10]. This means a single KE, such as "Reduced Granulosa Cell Proliferation," can be part of multiple pathways, and the KERs that describe its connection to other events are developed independently [12] [9].

Quantitative Assessment of Key Event Relationships

Evidence and Confidence Assessment for KERs

The establishment of a scientifically credible KER requires a structured assessment of supporting evidence. Confidence in a KER is evaluated based on biological plausibility, essentiality, and empirical support [9]. The OECD's AOP Developers' Handbook provides a framework for this evaluation, guiding developers to document the weight of evidence supporting each hypothesized relationship [9].

Table 1: Evidence Types Supporting Key Event Relationships

| Evidence Category | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Plausibility | The relationship is consistent with established biological knowledge and mechanisms. | Established pathway from molecular biology; understood biochemical cascade [9]. |

| Essentiality | The upstream Key Event is necessary for the downstream Key Event to occur. | Experimental modulation (e.g., inhibition, knockout) of the upstream KE prevents the downstream KE [9]. |

| Empirical Support | Observational or experimental data demonstrates a consistent, quantifiable relationship between the KEs. | Dose-response, temporal, and incidence concordance between the two KEs from in vitro or in vivo studies [12] [9]. |

| Consistency & Specificity | The relationship is observed across multiple studies and is not a general, non-specific effect. | Replication across independent laboratories, models, or chemical stressors [9]. |

Essentiality is a critical concept, indicating that a KE plays a causal role in the pathway. If a given KE is prevented or fails to occur, progression to subsequent KEs in the pathway will not happen, thereby confirming its essential nature [9].

Quantitative KER Analysis and Parameters

For a KER to be predictive, the relationship between the upstream and downstream key events must be characterized as quantitatively as possible. This involves defining the conditions under which the progression from one event to the next can be expected [9]. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recommends documenting quantitative understanding for KERs to enhance their utility in predictive modeling [9].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters for Assessing KERs

| Parameter | Description | Utility in Risk Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Dose-Response Concordance | The relationship between the dose/concentration of a stressor that causes the upstream KE and the dose that causes the downstream KE. | Predicts the potency required to drive the pathway forward; helps set exposure thresholds [9]. |

| Temporal Concordance | The time-course of the upstream KE occurrence relative to the downstream KE. | Establishes a plausible sequence of events; informs the timing for biomarker monitoring [9]. |

| Incidence Concordance | The proportion of test subjects or systems exhibiting the upstream KE that also exhibit the downstream KE. | Provides data on the strength and consistency of the relationship [9]. |

| Response-Response Relationship | A mathematical function describing how the magnitude or incidence of the upstream KE influences the downstream KE. | Enables quantitative prediction of downstream effects based on measurement of upstream events [10]. |

Tools like Effectopedia, part of the AOP Knowledge Base (AOP-KB), are designed to assemble data on these quantitative relationships, further strengthening the predictive power of the AOP framework [10].

Case Study: KER in a Defined AOP for Female Fertility

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

A specific example of a KER development is demonstrated in research linking Androgen Receptor (AR) antagonism to reduced granulosa cell proliferation in ovarian follicles (KER2273), which is part of AOP 345 on reduced female fertility [12]. The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the logical relationships within this AOP segment.

The methodology for establishing this KER involved a systematic approach to ensure all relevant supporting evidence was retrieved and assessed for quality [12]. The workflow can be broken down into key experimental stages:

- KE Identification and Definition: The two adjacent Key Events (AR signaling and granulosa cell proliferation) were first developed and defined as discrete, measurable units [12].

- Evidence Retrieval: A systematic literature search was conducted to gather all available evidence linking the two events, focusing on studies in gonadotropin-independent follicles [12].

- Evidence Quality Assessment: The retrieved empirical evidence was critically assessed for its quality, reliability, and relevance [12].

- Plausibility and Essentiality Evaluation: Biological plausibility was established based on the understood role of AR in early follicular development. Essentiality was supported by data showing that disruption of AR action impairs this critical process [12].

- KER Documentation: The relationship (KER2273) was formally documented in the AOP-Wiki, including all supporting evidence and quantitative understandings, following OECD guidance [12] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions for KER Investigation

Studying a KER such as the one between AR antagonism and reduced granulosa cell proliferation requires specific research tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating KER2273

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| AR Antagonists (e.g., Hydroxyflutamide) | Used as model stressors to specifically inhibit the Molecular Initiating Event (AR activation) and trigger the pathway [12]. |

| Primary Granulosa Cell Cultures | An in vitro model system to isolate and study the direct effects of AR antagonism on granulosa cell biology, excluding systemic confounders [12]. |

| Proliferation Assays (e.g., BrdU/EdU, MTT) | Quantitative methods to measure the downstream Key Event of reduced cell proliferation. These provide empirical data for dose-response and temporal concordance [12]. |

| Gene Expression Analysis (qPCR, RNA-Seq) | Tools to measure changes in transcript levels of AR-target genes, providing evidence for the upstream Key Event of decreased AR signaling [12]. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for AR | Used on ovarian tissue sections to localize and semi-quantify AR protein, confirming the presence of the molecular target in the relevant cell type [12]. |

This case study underscores the strategy of tackling isolated KERs as building blocks, which can accelerate the overall development of AOPs and, in turn, facilitate the creation of simple test methods for chemical screening and risk assessment [12].

Implementation and Regulatory Applications

From KERs to AOP Networks and Predictive Toxicology

While individual KERs are the modular building blocks, they are functionally assembled into AOP networks for most real-world applications [5] [9]. These networks provide insight into the complex interactions among biological pathways and can account for multiple stressors or MIEs leading to a common adverse outcome [5]. The primary application of these structured KERs and AOPs is in New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). AOPs are a critical component in building confidence in using in vitro NAMs data to predict adverse outcomes, thereby reducing reliance on animal testing [5]. For instance, EPA researchers use AOPs to develop in vitro methods for identifying carcinogenic chemicals and to understand the effects of chemical exposure on endpoints like developmental neurotoxicity [5]. The quantitative understanding captured in KERs allows risk assessors to use measurements of an upstream key event (e.g., from a high-throughput assay) to predict the likelihood and magnitude of a downstream adverse outcome, informing decisions on chemical safety [5] [9].

Accessing KERs and AOPs: Knowledge Bases and Tools

The collaborative and living nature of the AOP framework is supported by several key online resources:

- AOP-Wiki: A globally accessible platform and central repository for developing and disseminating AOP descriptions, including KERs, in accordance with OECD guidance [5] [9]. It is the most densely populated module of the AOP Knowledge Base (AOP-KB) [10].

- OECD-Endorsed AOPs: The OECD provides a repository of AOPs that have undergone a rigorous scientific review and endorsement process, providing a high level of confidence for regulatory use [5].

- Effectopedia: An open-source software platform designed for collaborative AOP development, with a strong focus on capturing quantitative and probabilistic relationships for KERs [10].

These platforms ensure that KERs and AOPs remain living frameworks, continuously updated and refined as new scientific evidence emerges [9] [10]. This dynamic characteristic is crucial for maintaining the relevance and scientific integrity of the AOP framework in advancing predictive toxicology and risk assessment.

Five Foundational Principles of AOP Development

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework is a conceptual construct that portrays existing knowledge concerning the sequence of causal events leading from a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) to an Adverse Outcome (AO) at a level of biological organization relevant for risk assessment [13]. This whitepaper delineates the five foundational principles that guide the systematic development, evaluation, and application of AOPs. These principles ensure that AOPs are robust, reliable, and fit-for-purpose in supporting chemical safety assessment and regulatory decision-making, particularly in translating data from New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) to predictable adverse effects [2].

Principle 1: AOPs are Conceptual and Not Stressor-Specific

An AOP describes a generalized sequence of biological effects that can be expected for any stressor that triggers a specific Molecular Initiating Event [2]. The framework focuses on the biological pathway itself, independent of any specific chemical or stressor that might initiate it.

- Underlying Rationale: This principle emphasizes the modularity and reusability of AOP knowledge. A single AOP, such as "Aromatase Inhibition Leading to Reproductive Dysfunction" [7], can be applicable to any chemical that inhibits the aromatase enzyme, allowing for a generalized understanding of the toxicity pathway.

- Practical Implication: It allows regulators and researchers to use one well-established AOP to predict the potential hazard of entire classes of chemicals that share a common mechanism of action, thereby increasing the efficiency of chemical risk assessment [2].

Principle 2: AOPs are Modular and Composed of Key Events and Key Event Relationships

The structure of an AOP is modular, built from discrete, measurable Key Events (KEs) connected by scientifically supported Key Event Relationships (KERs) [13]. This modularity facilitates the assembly of AOP networks from existing, validated components.

- Key Definitions:

- Molecular Initiating Event (MIE): The initial interaction between a stressor and a biomolecule within an organism that starts the AOP [2] [13].

- Key Event (KE): A measurable change in biological state that is essential to the progression of the AOP toward the adverse outcome. KEs exist at different levels of biological organization (cellular, tissue, organ, organism) [13].

- Key Event Relationship (KER): A description of the causal or mechanistic linkage between two KEs. A KER defines how a change in an upstream event can be used to predict a change in a downstream event [13].

- Structural Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and modular components of AOP development.

Principle 3: Key Events Must Be Essential and Measurable

For a biological change to be designated a Key Event in an AOP, it must be both measurable and essential for the progression to the Adverse Outcome [13]. Essentiality implies a causal role, meaning that if the KE is prevented, progression to subsequent KEs and the AO will not occur.

- Experimental Validation of Essentiality: The handbook recommends specific approaches to evaluate essentiality [13]:

- Biological Plausibility: The KE should be consistent with established biological knowledge.

- Empirical Support: Experimental evidence should demonstrate that the upstream KE causes the downstream KE.

- Essentiality Testing: Studies that experimentally modulate or inhibit a KE (e.g., through pharmacological inhibitors or genetic knockout) should demonstrate a consequent prevention of all downstream KEs and the AO.

- Quantitative Understanding: The conditions under which a change in an upstream KE will cause a change in a downstream KE should be described as quantitatively as possible, including aspects of timing, magnitude, and incidence [2] [13].

Principle 4: Development is Guided by Weight of Evidence and Quantitative Understanding

Confidence in an AOP for regulatory application is established through a systematic Weight of Evidence (WoE) assessment based on modified Bradford-Hill criteria [7] [13]. A key goal is the transition from qualitative AOPs to Quantitative AOPs (qAOPs).

- Weight of Evidence Criteria:

- Biological Plausibility: The degree to which the relationship between KEs is supported by established biological knowledge.

- Empirical Support: The strength and consistency of experimental data demonstrating that a change in the upstream KE leads to a predictable change in the downstream KE.

- Quantitative Understanding: The availability of data that defines the dose-response, temporal, and incidence relationships between KEs [2].

- qAOP Development Methods: A review of OECD-endorsed AOPs reveals that quantitative understanding can be presented and utilized in various ways to build qAOPs [7]:

- Response-Response Relationships: Using regression analysis to fit mathematical functions to data linking two KEs.

- Biologically-Based Mathematical Modeling: Using systems of ordinary differential equations to represent the underlying biology.

- Bayesian Networks: Using probabilistic models to describe complex AOPs with multiple pathways, capable of handling uncertainty.

Table 1: Categories of Quantitative Understanding (QU) in OECD-Endorsed AOPs (Based on a 2021 Review) [7]

| AOP ID | AOP Title | KERs with Low QU-WoE | KERs with Moderate QU-WoE | KERs with High QU-WoE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOP 3 | Inhibition of mitochondrial complex I leading to parkinsonian motor deficits | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| AOP 25 | Aromatase inhibition leading to reproductive dysfunction | 1 | 7 | 0 |

| AOP 131 | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation leading to uroporphyria | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| AOP 54 | Inhibition of Na+/I- symporter leads to learning/memory impairment | 10 | 3 | 2 |

Principle 5: AOPs are Living Documents in a Collaborative Knowledgebase

AOPs are not static documents but evolving representations of scientific knowledge. They are intended to be updated and refined as new evidence emerges [2] [13]. The primary repository for this knowledge is the AOP-Wiki, which facilitates collaborative development and peer review.

- The AOP Development Workflow: The process is iterative and community-driven. The generalized workflow, as outlined in the AOP Developer's Handbook, is shown below [13].

- Endorsement and Versions: The OECD oversees a formal peer-review process, endorsing specific "snapshots" of AOPs. However, the living version in the AOP-Wiki continues to incorporate new knowledge, with tools available to track changes between versions [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources in AOP Framework Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application in AOP Research |

|---|---|

| AOP-Wiki (aopwiki.org) | The primary collaborative knowledgebase for AOP development. It provides the platform for drafting, sharing, and peer-reviewing AOPs, KEs, and KERs [13]. |

| SeqAPASS Tool | A computational tool used to evaluate the conservation of molecular targets (like protein sequences) across species, supporting cross-species extrapolation in AOP application [2]. |

| In Vitro High-Throughput Screening Assays | These assays generate data on Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs) and early cellular Key Events, which can be used as inputs for AOP-based prediction of higher-order effects [2]. |

| Biomarker Assays | Validated analytical methods (e.g., ELISA, qPCR, immunohistochemistry) for measuring specific Key Events at the molecular, cellular, or tissue level in experimental studies [13]. |

| OECD AOP Developers' Handbook | The definitive guide providing practical instructions, templates, and WoE evaluation criteria for developing and assessing AOPs according to international standards [13]. |

The AOP framework is a powerful tool for structuring toxicological knowledge to support predictive risk assessment. Its utility and scientific credibility are anchored in the five foundational principles of being conceptual and not stressor-specific, modular in construction, reliant on essential and measurable key events, guided by rigorous weight of evidence and quantitative understanding, and existing as living documents. Adherence to these principles ensures that AOPs can effectively bridge the gap between mechanistic data from new approach methods and the adverse outcomes required for regulatory protection of human health and the environment.

The Role of the AOP Knowledge Base (AOP-KB) and OECD Programme

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework is a conceptual structure that organizes toxicological knowledge into a sequential chain of measurable biological events, linking a molecular-level initiating event to an adverse outcome of regulatory concern [2]. This framework provides a standardized approach for understanding toxicity mechanisms and supporting chemical safety assessment without sole reliance on traditional animal testing [14]. The AOP Knowledge Base (AOP-KB) is the central repository developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to enable the global scientific community to collaboratively develop, share, and discuss AOP-related knowledge [15]. The AOP-KB represents a foundational resource for advancing 21st-century toxicology by facilitating the use of mechanistic data for predictive risk assessment and promoting the adoption of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that reduce dependence on animal studies [2] [16].

AOP-KB Architecture and Core Components

The AOP-KB is not a single system but rather a combination of four independently developed yet interoperable platforms, each serving a distinct function in AOP development and utilization [15]. These platforms synchronize and exchange data through a central AOP-KB Hub, creating a comprehensive knowledge ecosystem [15].

Table 1: Core Platforms of the AOP Knowledge Base

| Platform Name | Primary Function | Development Status |

|---|---|---|

| AOP-Wiki | Primary authoring tool for qualitative AOP development using a wiki interface; organizes knowledge via crowd-sourcing [15] [17]. | Fully operational [15] |

| Effectopedia | Modeling platform for collaborative development of AOPs with visual representation of knowledge and algorithms [15]. | Beta release available [15] |

| Intermediate Effects DB | Hosts chemical-related data from non-apical endpoint methods and links compounds to Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs) and Key Events (KEs) [15]. | Under development [15] |

| AOP Xplorer | Computational tool for automated graphical representation of AOPs and their networks [15]. | Under development [15] |

The AOP-Wiki serves as the primary entry point and user interface for most AOP development activities [17]. It employs controlled-vocabulary drop-down lists to facilitate the entry of ontology-based information, ensuring consistency in how biological objects, methods, life stages, and species are described across different AOPs [15]. This platform supports the OECD review process for AOPs and allows users to create snapshots of AOPs in PDF format for offline access [17].

The governance of the AOP-KB, particularly the AOP-Wiki, is managed by the AOP Knowledgebase Coordination Group (AOP-KB CG), composed of individuals and organizations that contribute financially or through substantial donations of time and expertise [17]. Membership is renewed annually, and new members can be accepted with the approval of the current CG [17].

The OECD AOP Programme: Governance and Development

The OECD AOP Programme was introduced in 2012 and is overseen by the Extended Advisory Group on Molecular Screening and Toxicogenomics (EAGMST) [18]. Its primary mission is to coordinate international AOP development, provide a standardized knowledge base, support regulatory uptake, and promote the global use of AOPs in chemical safety assessment [18]. The programme has established formal guidance documents including the "Guidance Document for Developing and Assessing Adverse Outcome Pathways" and the "Users' Handbook supplement to the Guidance Document" to ensure consistent and scientifically rigorous AOP development [18].

A critical initiative within the OECD programme is the AOP Coaching Program, launched in 2019 to pair novice AOP developers with experienced coaches [19]. This program aims to harmonize AOP development according to OECD guidance, while also initiating "gardening" efforts to remove redundant or synonymous Key Events in the AOP-Wiki [19]. These efforts improve AOP network creation, promote the reuse of extensively reviewed Key Events, and ensure the development of high-quality AOPs with enhanced regulatory utility [19].

The AOP development process under the OECD programme involves several critical stages:

- Knowledge Assembly: Expert collaboration to assemble existing biological knowledge and evidence into the structured AOP format [18].

- Weight-of-Evidence Assessment: Systematic evaluation of the evidence supporting each Key Event Relationship (KER) using established criteria including biological plausibility, empirical support, and quantitative understanding [2] [16].

- Scientific Review: Formal review of the assembled AOP by scientific experts to ensure accuracy and completeness [18].

- OECD Endorsement: Final endorsement by OECD working groups for AOPs with demonstrated regulatory relevance [17].

A more pragmatic approach to AOP development has recently been proposed, focusing on Key Event Relationships (KERs) as the core building blocks rather than attempting to develop complete AOPs in a single effort [16]. This approach recognizes that establishing causal links between pairs of Key Events is the most evidence-intensive part of AOP development and advocates for using systematic review approaches primarily for KERs that are not based on canonical knowledge [16].

Practical Application in Research and Regulatory Science

AOP-Based Research Methodologies

The AOP framework enables several advanced research methodologies that support modern chemical safety assessment:

- In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation: Using AOPs to translate mechanistic data from in vitro systems to predictions of in vivo toxicity [2]. For example, a chemical causing a specific DNA mutation in an in vitro screening assay (MIE) can be evaluated for potential carcinogenicity (AO) through a well-established AOP [2].

- Cross-Species Extrapolation: Addressing uncertainty in risk assessment by evaluating the conservation of pathways across species [2]. Tools like the EPA's SeqAPASS can confirm structural conservation of molecular targets (e.g., estrogen receptors) between test species and untested species, supporting extrapolation of AOP-based predictions [2].

- Complex Mixtures Assessment: Using AOP networks to understand and predict the combined effects of chemical mixtures [2]. When multiple chemicals share a Key Event (e.g., reduced maternal thyroid hormone levels) leading to the same adverse outcome (e.g., reduced birthweight), they may exhibit dose-additive effects that can be informed by AOP knowledge [2].

- Hypothesis-Driven Testing: Focusing traditional testing on sensitive species, life stages, and toxicity endpoints informed by AOP knowledge [2]. For instance, knowing that estrogen-mimicking chemicals bind to estrogen receptors (MIE) and lead to changed sex ratios in fish (AO) guides targeted exposure studies using surrogate fish species [2].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AOP Development

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application in AOP Context |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Assay Systems | Receptor binding assays, transcriptional activation assays, high-content screening platforms | Measure Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs) and cellular-level Key Events [2] |

| Omics Technologies | Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics platforms | Generate mechanistic data supporting Key Event Relationships and identifying novel Key Events [14] |

| Computational Toxicology Tools | QSAR models, molecular docking simulations, pharmacokinetic modeling software | Predict chemical interactions with biological targets (MIEs) and quantitative relationships between Key Events [2] [16] |

| Cross-Species Extrapolation Tools | SeqAPASS tool for protein sequence conservation analysis | Evaluate conservation of Molecular Initiating Events and Key Events across species to support ecological risk assessment [2] |

Current Status and Future Directions

As of 2025, the AOP-KB continues to evolve with several ongoing international initiatives. The Society for the Advancement of Adverse Outcome Pathways (SAAOP), which now affiliates with both the American Society for Cellular and Computational Toxicology (ASCCT) and the European Society for Toxicology In Vitro (ESTIV), plays a crucial role in supporting the AOP developer and user communities [17]. The SAAOP Knowledgebase Interest Group (SKIG), comprising over 40 international experts, focuses on hands-on improvements to the AOP framework and AOP-Wiki [14]. Recent SKIG activities have addressed ontology-based harmonization, AI tools for AOP development, integration of omics data, and automated access to AOP-Wiki contents [14].

Future directions for the AOP-KB and OECD programme include enhancing the quantitative aspects of AOPs to support more predictive toxicology, expanding AOP networks to capture complex biological systems more comprehensively, and strengthening the formal ontologies that underpin the AOP-KB to improve computational accessibility and integration [14]. There is also a growing emphasis on developing structured approaches to establish AOPs as a reliable foundation for regulatory decision-making, particularly in the context of the European Union's policy on animal protection and its roadmap toward phasing out animal testing for chemical safety assessments [14].

The AOP framework's strength lies in its ability to organize decentralized knowledge into a structured format that explicitly defines the evidence supporting causal connections between toxicological events [2] [16]. As the AOP-KB continues to mature, it is progressively fulfilling its potential as a central resource for transforming chemical safety assessment through mechanism-based understanding of toxicity.

Distinguishing AOPs from Mode of Action (MoA) and Risk Assessment

In modern toxicology and drug development, precisely defining how chemicals cause adverse effects is crucial for risk assessment and regulatory decision-making. The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework has emerged as a powerful conceptual tool that organizes biological knowledge into a structured format, distinguishing it from, yet relating it to, established concepts like Mode of Action (MoA) and the comprehensive process of Risk Assessment. AOPs represent a paradigm shift towards a pathway-based approach for characterizing the inherent hazard of chemicals, which can be applied independently of any specific chemical stressor to support predictive toxicology [20]. This framework allows researchers and regulators to use mechanistic data from New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) to predict adverse outcomes, thereby reducing reliance on traditional animal testing [2] [5]. Understanding the distinctions and intersections between AOPs, MoA, and Risk Assessment is fundamental for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to apply these concepts effectively in safety evaluations and regulatory submissions.

Defining the Concepts: AOP, MoA, and Risk Assessment

What is an Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP)?

An Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) is an analytical construct that describes a sequential chain of causally linked events at different levels of biological organisation that lead to an adverse health or ecotoxicological effect [3]. It is not a specific pathway for a single chemical, but rather a generalizable framework that depicts a sequence of biological effects expected for any stressor that triggers a particular Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) [2].

The key components of an AOP are:

- Molecular Initiating Event (MIE): The initial interaction between a stressor (e.g., a chemical) and a biomolecule (e.g., a receptor, enzyme, or DNA) within an organism [2] [5].

- Key Events (KEs): Measurable biological changes at the cellular, tissue, or organ level that occur between the MIE and the Adverse Outcome. These are viewed as "essential" steps in the pathway [2].

- Key Event Relationships (KERs): Descriptions of the causal linkages between KEs, explaining how one event leads to the next. KERs are supported by evidence of biological plausibility, empirical support, and quantitative understanding [2].

- Adverse Outcome (AO): A biological change at the organism or population level considered relevant for risk assessment or regulatory decision-making (e.g., impacts on survival, growth, reproduction, or human health) [3] [5].

AOPs are conceptualized as a series of "biological dominos," where the falling of one domino (a KE) triggers the next in a cascade towards an adverse outcome [2] [5]. They are modular, can be assembled into networks, and are considered "living documents" that are refined as new biological evidence emerges [2].

What is Mode of Action (MoA)?

Mode of Action (MoA) describes a functional or anatomical change, at the cellular level, resulting from the exposure of a living organism to a substance [21] [22]. It is an intermediate level of complexity that sits between detailed molecular mechanisms and overall physiological outcomes. In the context of the International Program on Chemical Safety (IPCS) framework, an MoA is defined as a series of key events along a biological pathway from the initial chemical interaction through to the toxicological outcome [20].

It is critical to distinguish MoA from the more specific term Mechanism of Action (MOA), which refers to the precise biochemical interaction at the molecular level, such as the specific binding of a drug to an enzyme or receptor [21]. For example, a Mechanism of Action could be "binding to DNA," whereas the broader Mode of Action would be "transcriptional regulation" [22]. While an MoA does not need to be complete to be useful, its application depends on its level of completeness [20].

What is Risk Assessment?

Risk Assessment is a comprehensive, multi-step process used to characterize the nature and probability of adverse health or ecological effects resulting from exposure to a hazard. The US EPA and other regulatory bodies use it to inform regulatory decisions. Crucially, AOPs are not risk assessments [2]. While AOPs inform the characterization of hazard or effect, they do not explicitly address exposure, which is a key component of a risk assessment [2]. Risk assessment integrates hazard identification (for which AOPs can be a tool) with exposure assessment to determine the overall risk under specific conditions.

Comparative Analysis: AOP vs. MoA vs. Risk Assessment

The table below summarizes the core distinctions between these three concepts.

Table 1: Key Differences Between AOP, MoA, and Risk Assessment

| Feature | Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) | Mode of Action (MoA) | Risk Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition & Scope | A conceptual framework organizing knowledge about a sequence of causally linked events from an MIE to an AO [2] [3]. | A description of the key functional and anatomical changes at the cellular level leading from a chemical interaction to a toxicological outcome [20]. | A comprehensive process integrating hazard, exposure, and dose-response to characterize risk [2]. |

| Specificity | Not stressor-specific; a generalized pathway applicable to any chemical causing the defined MIE [2]. | Traditionally describes the pathway for a specific chemical causing toxicity in a specific context [2] [20]. | Chemical- and scenario-specific; evaluates risk for a specific stressor under defined exposure conditions. |

| Primary Function | Hazard identification and mechanistic understanding; a tool for organizing data and predicting effects [2] [5]. | Establishing a causal chain for a specific chemical's toxicity to determine human relevance [20]. | Informing regulatory decisions and risk management by quantifying the probability of an adverse effect. |

| Relationship to Exposure | Does not include exposure assessment; begins with a biological interaction (MIE) [2]. | Implicitly includes exposure (as it starts with a specific chemical) but focuses on the subsequent biological pathway. | Explicitly includes exposure assessment as a core component. |

| Composition | Modular structure of MIE, KEs, KERs, and AO [2]. | A series of key events, established using Bradford-Hill criteria for causation [20]. | Integrates hazard identification, dose-response assessment, exposure assessment, and risk characterization. |

Visualizing the Relationship Between an AOP and a Chemical-Specific MoA

The following diagram illustrates how a generalized AOP serves as a knowledge framework to inform the development of a chemical-specific MoA, which in turn is used within a broader Risk Assessment that incorporates exposure science.

Figure 1: The role of AOPs in risk assessment. A generalized AOP framework informs the development of a chemical-specific Mode of Action (MoA), which contributes to hazard identification within a comprehensive Risk Assessment that also incorporates exposure science.

Practical Application and Experimental Protocols

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Building and applying AOPs and MoAs requires a diverse set of experimental tools. The following table details essential reagents and methodologies used in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methods for AOP/MoA Investigation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in AOP/MoA Research |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Bioassays | High-throughput cell-based assays (e.g., Tox21 program) [20]; Receptor binding assays; Enzyme inhibition assays. | To identify potential Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs) and cellular-level Key Events (KEs) for thousands of chemicals rapidly. |

| 'Omics Technologies | Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Chemoproteomics [21]. | To generate mechanistic data and discover novel Key Events by measuring genome-wide changes in gene expression, protein abundance, or chemical-protein interactions. |

| Genetic Perturbation Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, siRNA [21]. | To establish causality for KEs by knocking out or knocking down a gene and testing if it abolishes the downstream pharmacological or toxicological effect (Reverse Genetics). |

| Microscopy & Imaging | Automated microscopy; Image analysis software [21]. | To detect phenotypic changes in cells (e.g., filamentation, blebbing) that serve as indicators of the MoA of a compound. |

| Computational & Modeling Tools | AOP-Wiki [3] [5]; SeqAPASS tool [2]; Pattern recognition algorithms [21]. | To develop and disseminate AOP knowledge; predict protein targets for small molecules; assess conservation of pathways across species. |

| Forphenicine | Forphenicine | Forphenicine is a potent alkaline phosphatase inhibitor and immunomodulator for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 5-Ethyl-5-(2-methylbutyl)barbituric acid | 5-Ethyl-5-(2-methylbutyl)barbituric acid, CAS:36082-56-1, MF:C11H18N2O3, MW:226.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodologies for Elucidating Key Events and Relationships

The process of building confidence in an AOP or MoA involves systematically gathering evidence for the Key Events and their causal relationships.

Identifying Key Events:

- Microscopy-based Methods: Treat target cells with the bioactive compound and observe phenotypic changes using (automated) microscopy. Changes such as conversion to spheroplasts (indicative of inhibited peptidoglycan synthesis) or filamentation (suggestive of inhibited DNA synthesis) provide clues about the MoA and potential KEs [21].

- Direct Biochemical Methods: A protein or small molecule drug candidate is labeled and traced throughout the body to identify its direct molecular targets through physical interaction, helping to define the MIE and early KEs [21].

- Omics-based Methods: Expose model systems to the stressor and use transcriptomics or proteomics to profile the global molecular changes. These profiles can be compared to those of compounds with known targets/MoAs to generate hypotheses about the KEs [21].

Establishing Causality for Key Event Relationships (KERs): The IPCS MoA framework uses a systematic approach, adapted from the Bradford-Hill criteria, to evaluate the evidence supporting the causal relationship between KEs [20]. The three pillars of evidence for a KER are:

- Biological Plausibility: The relationship should be consistent with the established biological knowledge of the system [2].

- Empirical Support: Experimental evidence must demonstrate that a change in the upstream KE leads to a predictable change in the downstream KE [2].

- Quantitative Understanding: Data should define the conditions (e.g., timing, magnitude) under which a change in the upstream KE is necessary and sufficient to cause a change in the downstream KE [2].

Workflow for AOP Development and Application

The diagram below outlines a generalized experimental workflow for developing an AOP and applying it for chemical safety assessment.

Figure 2: Workflow for AOP development and application. The process begins with hypothesis generation using chemical data, proceeds through iterative in vitro and mechanistic testing to identify Key Events, formalizes the pathway in the AOP-Wiki, and culminates in its application for safety assessment.

The distinctions between Adverse Outcome Pathways, Mode of Action, and Risk Assessment are foundational to modern, mechanistic toxicology. AOPs provide a generalized, non-stressor-specific knowledge framework for organizing biological events leading to an adverse outcome. In contrast, an MoA typically applies this knowledge to describe the causal pathway for a specific chemical. Both concepts are critical for hazard identification, but they are distinct from the comprehensive process of Risk Assessment, which integrates this hazard information with exposure science to quantify risk. The AOP framework, supported by international efforts from the OECD and the US EPA, serves as a translational tool that enhances the use of data from New Approach Methodologies [2] [3] [5]. By providing a structured and transparent way to represent biological knowledge, AOPs empower researchers and drug developers to make more informed predictions about chemical hazards, design targeted testing strategies, and ultimately build greater confidence in non-animal approaches for protecting human health and the environment.

Building and Applying Quantitative AOPs: From In Vitro Data to Regulatory Decisions

Transitioning from Qualitative to Quantitative AOPs (qAOPs)

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework has emerged as a critical tool in modern toxicology and chemical safety assessment, providing a structured approach to organize mechanistic data across multiple biological levels. While qualitative AOPs offer valuable conceptual frameworks, the transition to quantitative AOPs (qAOPs) represents a necessary evolution toward more predictive and reliable chemical risk assessment paradigms. This transition enables researchers to move beyond qualitative descriptions to mathematical models that can predict the probability and severity of adverse outcomes based on specific exposure conditions [23].

Q-AOPs are fundamentally toxicodynamic models built upon the foundation of qualitative AOPs but incorporate quantitative considerations of kinetics and dynamics. These models facilitate a more reliable prediction of chemically induced adverse effects by establishing dose-response relationships and response-response relationships across key events in the pathway [24]. The quantification of AOPs marks a significant advancement toward replacing traditional animal testing with mechanistically informed, human-relevant testing strategies based on in vitro and in silico approaches [25].

The core value of qAOPs lies in their ability to support regulatory decision-making by providing a scientific basis for identifying points of departure, establishing safety thresholds, and ultimately characterizing human and ecological risks. By incorporating quantitative parameters, these models allow for more precise extrapolations—from in vitro to in vivo conditions, across species, and from high to low exposure scenarios [24] [4].

Theoretical Foundation of qAOPs

Core Components and Definitions

A quantitative Adverse Outcome Pathway expands upon the qualitative AOP framework by incorporating mathematical relationships that define the connections between molecular initiating events (MIEs), key events (KEs), and the adverse outcome (AO). According to established literature, a full qAOP model represents any mathematical construct that models the dose-response or response-response relationships of all key event relationships (KERs) described in an AOP. Similarly, a partial qAOP models these relationships for more than one KER, while a quantitative KER focuses on modeling a single dose/response-response relationship [24].

The mathematical foundation of qAOPs allows for explicit incorporation of complex biological phenomena that are often embedded within descriptive AOPs, including feedback loops, biological thresholds, and signaling cascades. Models that incorporate these complex relationships can generate predictions with greater biological fidelity, thereby enhancing their utility in hazard and risk assessment contexts [24]. The qAOP framework effectively bridges the gap between qualitative pathway descriptions and the quantitative requirements of modern risk assessment, supporting the identification of early biomarkers that can lead to earlier diagnosis of disease or prediction of adverse effects measurable by in vitro assays [24].

Distinguishing Qualitative and Quantitative AOPs

Table 1: Comparison between Qualitative AOPs and Quantitative AOPs

| Feature | Qualitative AOP | Quantitative AOP |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Organizing mechanistic knowledge | Predicting probability and severity of adverse outcomes |

| Key Event Relationships | Descriptive, conceptual linkages | Mathematical functions (regressions, differential equations) |

| Dose-Response | Not inherently considered | Central component of the model |

| Temporal Aspects | Often implied rather than explicit | Explicitly modeled dynamics |

| Regulatory Application | Hazard identification | Risk characterization and safety assessment |

| Data Requirements | Mechanistic evidence from various sources | Quantitative data on response thresholds and kinetics |

| Extrapolation Capability | Limited to qualitative inferences | Supports in vitro to in vivo and cross-species extrapolation |

The transition from qualitative to quantitative AOPs represents a paradigm shift in toxicological assessment. While qualitative AOPs systematically structure knowledge about the cascade of key events from molecular initiating events to adverse outcomes, quantitative AOPs incorporate sufficient information to describe dose-response relationships and temporal patterns among these components. This quantification enables the identification of points of departure for calculating external doses needed to cause hazardous effects, making qAOPs indispensable for integrating dose-response assessment with exposure assessment [24].

Quantitative Modeling Approaches for AOPs

Mathematical Frameworks for Quantification

The development of qAOPs employs diverse mathematical approaches, each with distinct strengths and applications. The choice of modeling methodology depends on the biological complexity of the pathway, the nature of available data, and the specific questions requiring answers [24]. Useful AOP modeling methods range from statistical approaches and Bayesian networks to regression models and ordinary differential equations, with each method offering unique capabilities for representing biological relationships.

Bayesian Network (BN) formalism has gained particular popularity in qAOP development due to its ability to harmonize different types of data, provide a robust paradigm for causal modeling, and support prospective exploration of multiple hypotheses [4]. BN approaches have been successfully applied across various toxicity domains, including reproductive toxicity, developmental neural toxicity, cardiotoxicity, and kidney injury. The Dynamic Bayesian Network (DBN) represents an extension particularly suited for modeling repeated exposure scenarios, as it can capture the temporal evolution of key events across multiple exposures [4].

For more complex biological systems with well-characterized kinetics, ordinary differential equation (ODE) models offer a powerful alternative. These models can explicitly represent biochemical reactions, cellular signaling pathways, and physiological processes through mathematical equations that describe rate changes in key event biomarkers over time. ODE-based models typically require more extensive parameterization but provide greater mechanistic insight and predictive capability for interpolating across untested conditions [24].

Workflow for qAOP Development

The development of quantitative AOPs follows a systematic workflow that transforms qualitative biological knowledge into predictive mathematical models. Based on expert consensus and case study evaluations, a harmonized framework for qAOP development has emerged [23]. The process begins with question formulation, where modelers identify precisely what needs to be predicted to support the needs of end users or decision makers. This crucial first step ensures the model remains focused on addressing specific assessment goals [24].

The subsequent phase involves model structure definition, where the qualitative AOP serves as the conceptual foundation. Modelers must evaluate whether the existing AOP structure adequately represents the biological system or requires refinement or expansion to support quantitative predictions. This stage includes mapping the applicability domain of the underlying AOP to ensure it aligns with question requirements regarding species, life stages, temporal scales, and biological organization levels [24].

Following structure definition, the quantitative parameterization phase involves populating the model with mathematical relationships derived from experimental data. KERs are quantified using available evidence on dose-response and temporality, potentially derived from in vitro assays, in vivo studies, or existing literature. Finally, the model evaluation stage assesses predictive performance against independent datasets, with iterative refinement improving biological fidelity and predictive capability [24].

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing quantitative AOPs from qualitative foundations, showing the iterative process from problem definition to model application.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Q-AOP development relies on specialized software tools and computational resources that enable the construction, parameterization, and evaluation of quantitative models. The extensive and growing range of digital resources available to support qAOP modeling requires guidance for their practical application [23]. These resources span from general-purpose statistical packages to specialized modeling environments.

R statistical software has emerged as a predominant platform for qAOP development, providing comprehensive capabilities for Bayesian network analysis, differential equation modeling, and data visualization. The flexibility of R enables implementation of various modeling approaches, including the dynamic Bayesian networks used in recent proof-of-concept studies for repeated exposure scenarios [4]. Additionally, Microsoft Excel continues to serve as a valuable tool for initial data organization and preliminary analysis, particularly in the early stages of virtual dataset generation [4].

For specific modeling approaches, specialized tools offer enhanced capabilities. Bayesian network software such as Netica, GeNIe, or the bnlearn package in R provides dedicated environments for constructing and evaluating probabilistic networks. Differential equation modeling can be implemented through general mathematical computing environments like MATLAB or through specialized systems biology platforms such as COPASI or Virtual Cell. The selection of appropriate computational tools depends on the modeling methodology, data complexity, and required analytical capabilities [24] [4].

Experimental Assays and Biomarker Detection

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qAOP Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in qAOP Development |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Assay Systems | Primary hepatocytes, stem cell-derived cultures, 3D organoids | Provide human-relevant systems for quantifying key event responses |

| Biomarker Detection Kits | ELISA kits, Western blot reagents, PCR assays | Measure molecular and cellular key events with quantitative precision |

| Pathway Reporter Systems | Luciferase-based reporters, GFP-tagged pathway sensors | Enable dynamic monitoring of pathway activation in live cells |

| High-Content Screening Tools | Automated imaging systems, multi-parameter flow cytometry | Allow multiplexed measurement of multiple key events simultaneously |

| Toxicokinetic Tools | Mass spectrometry, radiolabeled compounds, protein binding assays | Quantify chemical distribution and metabolism relevant to MIE engagement |

| Reference Compounds | Prototypical pathway agonists and antagonists | Serve as positive controls for model validation and benchmarking |

The development of qAOPs requires reagents and assays capable of generating quantitative, dose-responsive data for key events in the pathway. These experimental tools must provide robust measurements across the relevant concentration ranges and exposure durations, with particular importance placed on assays that can capture early, predictive key events rather than solely measuring apical adverse outcomes [24]. For repeated exposure scenarios, assays must maintain viability and functionality over extended periods, potentially requiring specialized culture systems that support long-term homeostasis [4].

Advanced in vitro systems that incorporate metabolic competence, tissue-specific functionality, and cellular communication provide particularly valuable platforms for qAOP development. These systems better recapitulate the in vivo context in which adverse outcomes emerge, increasing the translational relevance of the quantitative relationships derived from them. Similarly, the inclusion of biomarker panels that capture multiple points along the pathway enables more comprehensive model parameterization and validation [4].