Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Development: A Strategic Framework for 21st Century Toxicology and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) development, a conceptual framework that organizes existing knowledge concerning biologically plausible links between molecular-level perturbation and adverse outcomes of...

Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Development: A Strategic Framework for 21st Century Toxicology and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) development, a conceptual framework that organizes existing knowledge concerning biologically plausible links between molecular-level perturbation and adverse outcomes of regulatory relevance. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological strategies, and practical applications of AOPs in modern toxicology. The content covers the transition from traditional testing to pathway-based approaches, details systematic development processes using international guidelines and collaborative platforms like the AOP-Wiki, and addresses common challenges in constructing robust AOPs. Furthermore, it examines advanced validation techniques, including quantitative AOPs (qAOPs) and computational integration, highlighting their crucial role in supporting chemical risk assessment, reducing animal testing, and informing regulatory decision-making for human health and ecological safety.

Understanding AOPs: The Foundational Principles and Framework Transforming Predictive Toxicology

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework is a conceptual construct that maps a sequential chain of measurable biological events from an initial molecular interaction to an adverse outcome of regulatory significance [1]. This framework provides a structured methodology for organizing biological knowledge concerning the mechanisms by which chemical stressors can induce adverse effects in individuals or populations. An AOP description commences with a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE), which represents the initial point of chemical interaction within an organism that starts the pathway. This MIE progresses through a dependent series of intermediate Key Events (KEs), which are measurable biological changes essential to the pathway's progression. The sequence culminates in an Adverse Outcome (AO), which is an effect considered relevant to risk assessment or regulatory decision-making [1]. The causal relationships between adjacent Key Events are explicitly described as Key Event Relationships (KERs), which facilitate the prediction of downstream events based on measurements of upstream events [1].

The fundamental purpose of the AOP framework is to support alternative toxicological approaches in chemical risk assessment, moving away from traditional reliance on apical endpoint animal testing and toward mechanistically based predictive toxicology. By systematically organizing existing knowledge, AOPs facilitate the evaluation of potential risks associated with exposure to various stressors, including chemicals and environmental contaminants [2]. The framework contributes significantly to understanding how specific and measurable biological perturbations cause adverse effects on human and environmental health, thereby supporting regulatory decisions worldwide [3]. The structured and consistent application of AOP principles helps build confidence in the applicability of the knowledge for decision-making in regulatory contexts, ultimately aiming to reduce animal testing, increase efficiency in chemical safety assessment, and provide deeper mechanistic insights into toxicity pathways.

Core Components of an AOP

Molecular Initiating Event (MIE)

A Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) is a specialized type of key event that represents the initial point of chemical or stressor interaction at the molecular level within an organism, resulting in a perturbation that initiates the AOP [1]. The MIE is the foundational event upon which the entire pathway is built, characterized by a specific molecular interaction between a stressor and a biological target. This interaction can take various forms, including covalent binding to proteins, interaction with specific receptors, inhibition of enzymatic activity, or damage to DNA. The essential requirement for an MIE is that it must be a definable, measurable molecular event that can be reproducibly identified and linked to the subsequent key events in the pathway.

Examples of well-characterized MIEs include the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by organophosphate pesticides [4], activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by dioxin-like compounds [1], and inhibition of thyroperoxidase leading to altered thyroid hormone synthesis [1]. A critical aspect of MIE definition is that it should be described as a discrete modular unit without reference to a specific adverse outcome or other key events, allowing it to be potentially incorporated into multiple AOPs where the same molecular interaction might lead to different adverse outcomes depending on the biological context [1].

Key Events (KEs) and Key Event Relationships (KERs)

Key Events (KEs) are defined as changes in biological or physiological state that are both measurable and essential to the progression of a defined biological perturbation leading to a specific adverse outcome [1]. Essentiality indicates that KEs play a causal role in the pathway, such that if a given KE is prevented or fails to occur, progression to subsequent KEs will not happen. While KEs are essential to progression along the AOP, they are not necessarily sufficient on their own to drive the pathway forward; the extent of pathway triggering is influenced by the intensity and duration of exposure to a stressor [1]. KEs typically exist at different levels of biological organization, spanning from molecular and cellular levels to tissue, organ, organ system, and whole organism levels.

Key Event Relationships (KERs) are scientifically based connections that link one key event to another, defining a causal and predictive relationship between an upstream and downstream event [1]. KERs facilitate the inference or extrapolation of the state of a downstream key event from the known, measured, or predicted state of an upstream key event. Each KER description should include information about biological plausibility, empirical support, and quantitative understanding of the relationship. The development of robust KERs is crucial for the predictive application of AOPs in risk assessment, as they provide the scientific basis for connecting measurable early key events to later occurring adverse outcomes that may be more difficult or time-consuming to measure directly.

Adverse Outcome (AO)

An Adverse Outcome (AO) is a specialized type of key event that is generally accepted as being of regulatory significance based on its correspondence to an established protection goal or equivalence to an apical endpoint in an accepted regulatory guideline toxicity test [1]. The AO represents the final event in the AOP sequence that is of direct relevance to risk assessment and regulatory decision-making. For human health AOPs, AOs are typically at the individual level (e.g., organ toxicity, cancer, developmental abnormalities), while for ecological AOPs, AOs may extend to population-level effects (e.g., reduced population sustainability, biodiversity loss) [4]. The AO must be clearly defined and measurable, with established relevance to protection goals to ensure the practical utility of the AOP for regulatory applications.

Quantitative Understanding of AOPs (qAOPs)

The transition from qualitative AOP descriptions to quantitative AOPs (qAOPs) represents a significant advancement in the framework's utility for risk assessment. A qAOP integrates quantitative data and mathematical modeling to provide a more precise comprehension of relationships between molecular initiating events, key events, and adverse outcomes [5]. The development of qAOPs is considered one of the main challenges remaining within the AOP framework, yet it is necessary to improve risk and hazard prediction [4]. When sufficient quantitative understanding of the relationships between key events exists, mathematical models can be developed to connect key events in a qAOP, ideally reducing the time and resources spent on chemical toxicity testing and enabling extrapolation of data collected at the molecular level to predict whether an adverse outcome may occur [4].

Table 1: Primary Methodologies for Quantitative AOP Development

| Methodology | Description | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systems Toxicology | Uses ordinary differential equations to represent biological mechanisms | High biological fidelity; can simulate dynamics | High data requirements; complex model development |

| Regression Modeling | Fitting functions to key event data (response-response method) | Simpler implementation; lower data requirements | Limited extrapolation capability; empirical rather than mechanistic |

| Bayesian Network Modeling | Probabilistic graphical models representing causal relationships | Handles uncertainty; useful for complex AOPs with multiple pathways | Cannot model feedback loops without extensions; requires probability distributions |

The development of qAOPs faces several significant challenges, including the availability and collection of quantitative data amenable to model development, the lack of studies that measure multiple key events simultaneously, and issues with model accessibility or transferability across platforms [4]. A review of AOPs with OECD status revealed that while confidence in qualitative relationships may be high, the conversion to qAOPs requires more specific, quantitative datasets that are often not readily available in the existing literature [4]. Furthermore, when quantitative data are available for a KER, challenges remain in extracting and standardizing it for quantitative model development, as data are presented in various formats ranging from text with cited references to tabulated forms and figures [4].

Experimental Protocols for AOP Development

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Literature Review and Evidence Gathering

Objective: To systematically identify, evaluate, and organize existing scientific evidence relevant to the proposed AOP.

Procedure:

- Define Search Strategy: Develop specific search terms related to the proposed MIE, intermediate KEs, and AO. Utilize structured search queries combining these terms.

- Database Searching: Execute searches across multiple scientific databases (e.g., PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus) to identify relevant literature.

- Evidence Collection: Screen abstracts and full texts for relevance to the AOP framework. Extract data on concentration-response, time-response, and incidence of biological effects.

- Evidence Mapping: Organize evidence according to the proposed KE and KER structure. Specifically identify studies that measure multiple key events, as these are particularly valuable for establishing quantitative relationships [4].

- Evidence Evaluation: Assess the quality and relevance of each study using predefined criteria. Categorize studies based on their utility for qualitative versus quantitative AOP development.

Applications: This protocol forms the foundation for AOP development, supporting both qualitative AOP description and subsequent quantitative modeling efforts. The process can be enhanced using computational tools such as AOP-helpFinder, which uses natural language processing and graph theory to systematically and rapidly explore available knowledge in scientific abstracts [2].

Protocol 2: Weight of Evidence Assessment for KERs

Objective: To systematically evaluate the strength and confidence in each Key Event Relationship using established Weight of Evidence (WoE) approaches.

Procedure:

- Biological Plausibility Assessment: Evaluate the strength of evidence supporting a causal relationship between KEup and KEdown based on current understanding of biological mechanisms.

- Empirical Support Evaluation: Assess the extent and consistency of observed co-occurrence or response-response relationships between KEup and KEdown across test systems, species, and stressors.

- Essentiality Determination: Evaluate evidence that modulation of KEup leads to corresponding changes in KEdown, and that inhibition of KEup prevents KEdown.

- Quantitative Understanding Analysis: Assess the availability and quality of quantitative data describing the relationship between KEup and KEdown, including concentration-response, time-course, and incidence data.

- Uncertainty and Inconsistency Documentation: Identify and document any inconsistencies in the evidence and significant data gaps that reduce confidence in the KER.

Applications: This protocol provides a standardized approach for evaluating confidence in individual KERs, which collectively informs the overall confidence in the AOP. This assessment is based on modified Bradford-Hill criteria involving biological plausibility, empirical support, and quantitative understanding [4].

Protocol 3: In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation for AOP Qualification

Objective: To establish quantitative relationships between in vitro assays measuring early KEs and in vivo outcomes for AOP application in chemical risk assessment.

Procedure:

- In Vitro System Characterization: Select and characterize appropriate in vitro systems that reliably measure early KEs (including MIE).

- Concentration-Response Modeling: Expose in vitro systems to a range of chemical concentrations and model concentration-response relationships for early KEs.

- Parallel In Vivo Studies: Conduct parallel in vivo studies measuring the same early KEs and downstream KEs across relevant tissues and biological levels.

- Pharmacokinetic Modeling: Develop pharmacokinetic models to relate in vitro concentrations to in vivo doses.

- Response-Response Modeling: Establish quantitative relationships between in vitro responses and in vivo outcomes using appropriate statistical models.

- Model Validation: Test the predictive performance of the quantitative relationships using additional test chemicals not included in model development.

Applications: This protocol enables the development of predictive models that can use in vitro data to forecast in vivo outcomes, supporting the use of AOPs in next-generation risk assessment where in vitro data may be used to prioritize chemicals for further testing or to identify potential hazards.

Visualization of AOP Components and Relationships

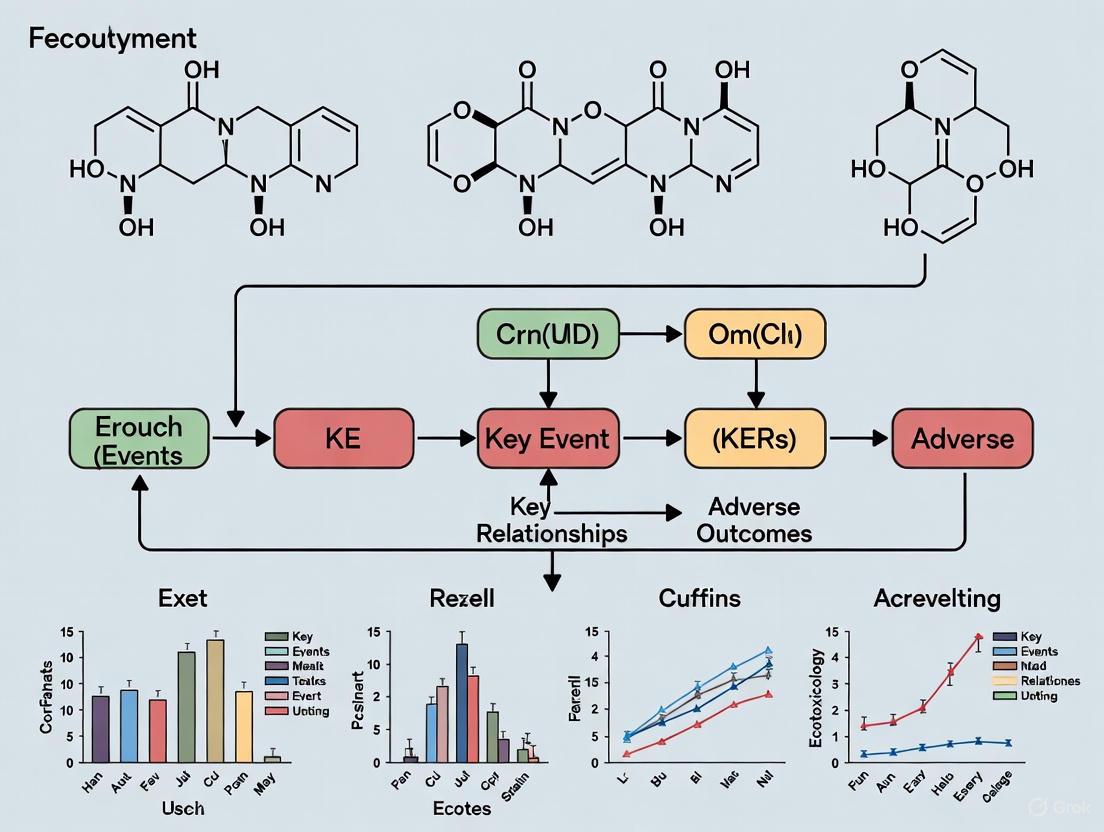

AOP Conceptual Framework and Development Workflow

Diagram 1: AOP Conceptual Framework. This diagram illustrates the linear progression of an Adverse Outcome Pathway from stressor interaction to adverse outcome through measurable key events.

Quantitative AOP Development Methodology

Diagram 2: qAOP Development Workflow. This diagram outlines the process for transitioning from qualitative AOP descriptions to quantitative AOP models using three primary methodologies.

Table 2: Key Research Resources for AOP Development and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in AOP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | AOP-helpFinder [2] | AI-powered literature mining to identify associations between stressors, molecular events, and adverse outcomes |

| Knowledge Bases | AOP-Wiki (aopwiki.org) [1] | Central repository for AOP descriptions, key events, and key event relationships |

| Modeling Platforms | Bayesian Network Software [5] | Probabilistic modeling of key event relationships under uncertainty |

| Experimental Models | In vitro bioassays [4] | High-throughput screening for molecular initiating events and early key events |

| Analytical Techniques | Transcriptomics, Proteomics [2] | Comprehensive measurement of biological changes at molecular levels |

The AOP framework provides a powerful structured approach for organizing mechanistic knowledge about toxicological processes, from molecular initiating events to adverse outcomes of regulatory concern. The core components of MIEs, KEs, and AOs, connected by scientifically supported KERs, create a modular knowledge framework that enhances our ability to predict chemical toxicity and support risk assessment decisions. The transition from qualitative AOP descriptions to quantitative AOP models represents the next frontier in the evolution of this framework, with promising methodologies including systems toxicology, regression modeling, and Bayesian network approaches [5]. However, significant challenges remain, particularly regarding the availability of quantitative data measuring multiple key events and the development of standardized approaches for qAOP construction.

International efforts, such as the OECD AOP Development Programme and the associated AOP Coaching Program, are contributing to more harmonized approaches to AOP development and the construction of AOP networks with enhanced regulatory utility [3]. As these efforts mature and computational tools for AOP development advance, the framework is poised to transform chemical risk assessment by incorporating deeper mechanistic insights, helping pinpoint knowledge gaps, and guiding future research directions [2]. The continued development and quantification of AOPs will ultimately strengthen the scientific basis for regulatory decisions aimed at protecting both human health and the environment.

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework is a conceptual construct that organizes existing knowledge concerning biologically plausible and empirically supported links between a molecular-level perturbation and an adverse outcome of regulatory relevance [6]. An AOP describes a sequential chain of causally linked events at different levels of biological organisation that lead to an adverse health or ecotoxicological effect [7]. This framework represents a transformative approach in toxicology, enabling greater integration of mechanistic data into chemical risk assessment and regulatory decision-making [8].

AOP development has emerged as a critical tool for addressing key challenges in regulatory toxicology, including the need to assess thousands of data-poor chemicals while reducing animal use, costs, and time required for chemical testing [6]. By providing a structured knowledge framework, AOPs support the use of different types of biological data to complement or potentially replace traditional in vivo animal studies [8]. The framework serves as a translational tool that enhances communication between scientists who generate toxicity data and the end users of this information, such as risk assessors and decision makers [8].

The Foundational Principles of AOP Development

The Five Core Principles

The development and application of AOPs are guided by five fundamental principles established through scientific discourse among AOP practitioners and formally recognized by international organizations including the OECD [6]:

- AOPs are not chemical specific

- AOPs are modular and composed of reusable components

- An individual AOP is a pragmatic unit of development and evaluation

- Networks of AOPs are the functional unit of prediction

- AOPs are living documents

These principles provide the foundation for consistent AOP development and address conceptual misunderstandings regarding the AOP framework and its application [6].

Visualizing the AOP Framework and Principles

The following diagram illustrates the core AOP structure and the relationships between its key components:

Figure 1: AOP Framework Structure. This diagram illustrates the sequential chain of events in an AOP, from stressor to Adverse Outcome (AO), and how core principles apply to different components. MIE: Molecular Initiating Event; KE: Key Event; KER: Key Event Relationship.

Detailed Examination of Core Principles

Principle 1: Chemical Agnosticism

Conceptual Foundation

The principle of chemical agnosticism states that AOPs are not stressor-specific [8] [6]. AOPs depict a generalized sequence of biological effects that can be expected for any stressor that directly changes a particular biological target defined by the Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) [8]. This means that several different chemicals could all trigger the same MIE for a given AOP [8]. The MIE represents the point where a chemical or non-chemical stressor directly interacts with a biomolecule to create a perturbation, and by definition occurs at the molecular level [6].

This principle emphasizes that AOPs describe biological pathways rather than chemical-specific pathways. The framework focuses on the biological trajectory from initial perturbation to adverse outcome, independent of the specific chemical that may initiate the sequence. This abstraction allows for greater generalization and application across multiple stressors sharing common mechanisms of action.

Practical Applications and Implications

The chemical-agnostic nature of AOPs enables several critical applications in chemical risk assessment:

- Chemical Categorization and Prioritization: AOPs facilitate the grouping of chemicals based on their potential to initiate specific MIEs, allowing for more efficient testing strategies and prioritization of chemicals with similar hazard characteristics [6].

- Assessment of Data-Poor Chemicals: For chemicals lacking extensive toxicity testing data, AOPs enable prediction of potential hazard based on knowledge of the MIE and the subsequent pathway [8].

- Evaluation of Chemical Mixtures: AOP networks provide insights into mixture effects by identifying points of convergence (shared KEs) among different chemicals [8].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Chemical Agnosticism in AOP Development

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | AOP Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Chemical-specific toxicity | Pathway-based biological response |

| Application | Limited to tested chemicals | Generalizable across chemical classes |

| Extrapolation | Based on structural similarity | Based on shared molecular targets |

| Regulatory Use | Chemical-specific risk assessment | Screening and prioritization of chemical categories |

Principle 2: Modularity and Reusable Components

Conceptual Foundation

The modularity principle states that AOPs are modular and composed of reusable components, notably Key Events (KEs) and Key Event Relationships (KERs) [6]. Any AOP can be represented as a sequence of "nodes" (KEs) and "edges" (KERs) linking those KEs together [8]. This modular structure allows for efficient knowledge assembly and reuse of established building blocks across multiple AOPs.

A Key Event represents a measurable change in biological state that is essential, but not necessarily sufficient, for the progression from a defined biological perturbation toward a specific adverse outcome [6]. Key Event Relationships define a directed relationship between a pair of KEs, identifying one as upstream and the other as downstream, and are supported by biological plausibility and empirical evidence [6].

AOP Networks as Functional Units

While individual AOPs represent practical units for development, the modular nature of AOP components enables the formation of AOP networks that represent the functional unit of prediction for most real-world scenarios [6]. Multiple AOPs sharing common KEs and/or KERs can be assembled into networks that capture the complexity of real biological systems [8]. These networks become more complete as more AOPs are defined [8].

The following diagram illustrates how modular AOP components form interconnected networks:

Figure 2: AOP Network from Modular Components. This diagram shows how multiple individual AOPs form networks through shared Key Events (KEs), creating the functional unit for prediction in real-world scenarios.

Practical Applications of Modularity

The modular design of AOPs enables several important applications:

- Efficient Knowledge Assembly: Once a KE or KER is defined and supported by evidence, it can be reused in multiple AOP contexts, reducing redundant effort in AOP development [6].

- Hypothesis-Driven Testing: Knowledge of modular components helps focus testing on critical gaps in understanding of specific KERs [8].

- Quantitative AOP Development: Modular components facilitate the development of quantitative understanding of how alterations in one KE impact downstream KEs [8].

- Cross-Species Extrapolation: Modular KEs and KERs enable evaluation of pathway conservation across species, addressing uncertainties in both human health and ecological risk assessment [8].

Principle 3: AOPs as Living Documents

Conceptual Foundation

The principle of AOPs as living documents recognizes that AOPs will evolve over time as new knowledge is generated [6]. AOPs are primarily a way of organizing information, and as new evidence and understanding supporting KERs and/or new methods for measuring KEs emerge, AOPs can be continually expanded or refined [8]. This dynamic nature ensures that AOPs remain current with scientific advances.

This principle acknowledges that our understanding of toxicological pathways is incomplete and continually evolving. The living document concept transforms AOPs from static descriptions into dynamic knowledge representations that improve in accuracy and utility as scientific knowledge advances.

Mechanisms for Evolution and Refinement

Several mechanisms support the ongoing evolution of AOPs:

- Structured Knowledge Management: The AOP-Wiki provides a globally accessible platform for developing and disseminating AOP descriptions in accordance with international guidance and templates [9]. This collaborative environment enables continuous refinement of AOP knowledge.

- Scientific Review Processes: The OECD has established formal processes for the scientific review of AOPs, including cooperation with scientific journals for peer review and publication [7].

- Evidence Integration: As new empirical data become available, particularly quantitative information on KERs, AOPs can be updated to reflect this enhanced understanding [6].

Table 2: Evolution of AOP Knowledge and Supporting Infrastructure

| Evolution Stage | Knowledge Status | Supporting Tools | Regulatory Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Development | Limited evidence for some KERs | AOP-Wiki for collaborative development | Hypothesis generation |

| Intermediate | Moderate evidence, some quantitative understanding | Effectopedia for quantitative data | Screening and prioritization |

| Mature | Strong empirical support for most KERs | AOP-KB with integrated data | Risk assessment support |

| Networked | Multiple interconnected AOPs with shared KEs | AOP-XPlorer for network analysis | Predictive toxicology |

Practical Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol for AOP Development Using Wiki Platform

Initial Setup and Planning

- Project Proposal: Submit an AOP project proposal for review by the Advisory Group on Emerging Science in Chemicals Assessment (ESCA) using the official form [7].

- Stakeholder Engagement: Identify and engage relevant scientific experts and potential end-users to form a development team.

- Scope Definition: Clearly define the Adverse Outcome based on regulatory relevance and the Molecular Initiating Event based on known molecular interactions.

AOP Wiki Development Process

- Account Creation: Register for an account on the AOP-Wiki (www.aopwiki.org) to access the primary development platform [7].

- Structured Entry: Follow the structured fields in the AOP-Wiki to ensure consistent organization of information:

- Complete the AOP title and summary information

- Define the Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) with detailed description

- Identify and describe sequential Key Events (KEs)

- Define Key Event Relationships (KERs) with supporting evidence

- Specify the Adverse Outcome (AO) and its regulatory relevance

- Evidence Documentation: For each KER, document three types of evidence:

- Biological plausibility

- Empirical support

- Quantitative understanding (if available)

Review and Endorsement Process

- Internal Review: Conduct iterative review within the development team to ensure consistency and completeness.

- Community Review: Utilize the collaborative features of the AOP-Wiki to solicit feedback from the broader scientific community.

- Formal Review: Submit the AOP for formal review through OECD processes or partner scientific journals [7].

- OECD Endorsement: Upon successful review, pursue official OECD endorsement for regulatory application.

Protocol for Quantitative AOP Development

Key Event Relationship Quantification

- Data Collection: Gather existing dose-response and temporal response data for each KE from literature and experimental studies.

- Response-Response Modeling: Develop mathematical relationships between upstream and downstream KEs using appropriate statistical models.

- Uncertainty Characterization: Quantify uncertainty in each KER using confidence intervals or Bayesian methods.

- Threshold Identification: Establish response thresholds for each KE that predict progression to the next event in the sequence.

Computational Implementation

- Platform Selection: Utilize appropriate platforms for quantitative AOP implementation:

- Model Integration: Incorporate computational models that represent quantitative understanding of KERs.

- Validation Testing: Compare quantitative AOP predictions with experimental data to assess predictive accuracy.

Application Notes for Specific Use Cases

Use Case 1: Chemical Prioritization and Screening

Application Protocol:

- Identify Relevant AOPs: Determine which AOPs are relevant to the regulatory endpoint of concern.

- Develop Testing Strategy: Design in vitro assays targeting MIEs and early KEs in relevant AOPs.

- Interpret Results: Use AOP knowledge to translate positive assay results into potential hazard identification.

- Risk-Based Prioritization: Combine AOP-based hazard information with exposure estimates for risk-based prioritization.

Considerations:

- AOPs inform hazard characterization but do not replace risk assessment [8]

- Consider the level of confidence in the AOP when making prioritization decisions [8]

- Account for species relevance when extrapolating from in vitro systems [8]

Use Case 2: Cross-Species Extrapolation

Application Protocol:

- Assess KE Conservation: Evaluate conservation of KEs across species using tools like EPA's SeqAPASS [8].

- Identify Sensitive Species: Determine which species may be most sensitive based on KE conservation and biological context.

- Quantitative Adjustment: Apply appropriate assessment factors based on quantitative differences in toxicological response across species.

- Confidence Assessment: Evaluate confidence in cross-species extrapolation based on strength of evidence for KE conservation.

Considerations:

- Molecular-level KEs (MIEs) generally show higher conservation across species than organ-level or individual-level outcomes [8]

- Consider differences in life stage, metabolism, and repair mechanisms when extrapolating across species [8]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for AOP Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Assembly Platforms | AOP-Wiki (www.aopwiki.org) | Primary platform for collaborative AOP development and qualitative knowledge organization [8] [7] |

| AOP Knowledge Base (AOP-KB) | Suite of web-based tools that brings together knowledge on how chemicals induce adverse effects [7] | |

| Quantitative AOP Tools | Effectopedia (www.effectopedia.org) | Open-source platform for assembling quantitative data on KE relationships and building quantitative AOPs [6] |

| AOP-XPlorer (www.aopxplorer.org) | Tool for visualization and analysis of AOP networks [6] | |

| Cross-Species Extrapolation | SeqAPASS | EPA tool for evaluating conservation of molecular targets and pathways across species [8] |

| Data Integration | OECD Harmonized Template 201 | Standardized format for capturing intermediate effects data from toxicity studies [6] |

| Training Resources | OECD Webinar Series | Training on testing and assessment methodologies [7] |

| AOP Training Videos | Recorded presentations maintained by the Animal-Free Safety Assessment Collaboration [8] |

The core principles of AOP development - chemical agnosticism, modularity, and evolution as living documents - provide a robust foundation for constructing scientifically credible and regulatory-relevant knowledge frameworks. These principles ensure that AOPs remain grounded in biological plausibility while supporting practical applications in chemical risk assessment and regulatory decision-making.

The chemical agnosticism principle enables application of AOP knowledge across multiple stressors, enhancing efficiency in chemical assessment. The modular design facilitates knowledge reuse and assembly into networks that better represent biological complexity. The living document concept ensures AOPs evolve with advancing scientific knowledge, maintaining their utility as translational tools between toxicological research and regulatory practice.

As the AOP knowledge base continues to expand through international collaborative efforts, these core principles will remain essential for maintaining scientific rigor and consistency in AOP development. The ongoing refinement of AOPs and their integration with new approach methodologies represents a paradigm shift in toxicology, moving toward more mechanistically informed and predictive chemical safety assessment.

Application Note: Advancing Predictive Safety Assessment Using AOPs

The landscape of toxicology is undergoing a fundamental shift from a descriptive science to a predictive, mechanism-based discipline. Central to this transformation is the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework, which provides a structured representation of causal relationships across multiple biological levels, from molecular initiating events to adverse organism-level outcomes [10]. This application note details how AOPs are being operationalized to address pressing regulatory challenges in drug development, particularly through the implementation of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that offer human-relevant safety data while reducing animal testing [11].

The essential premise of modern toxicology is being recontextualized as "the dose disrupts the pathway" rather than the traditional "the dose makes the poison" [10]. This paradigm shift emphasizes understanding the biological pathways disturbed by toxicants, which aligns perfectly with the AOP framework. In regulatory contexts, AOPs provide the scientific foundation for using mechanistic data from NAMs in chemical safety decisions, thereby addressing the critical need for more predictive and human-relevant toxicity testing strategies.

Quantitative Analysis of AOP-Based Model Performance

Recent validation studies have demonstrated the predictive capacity of AOP-informed models. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from cardiac liability assessment studies utilizing AOP-driven NAMs:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AOP-Informed Cardiac NAMs from Recent Studies

| Biological Pathway (Failure Mode) | Technology Platform | Key Endpoint Measured | Predictive Accuracy | Regulatory Context of Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Injury | Microfluidic BioFlux system with human aortic endothelial cells & THP-1 monocytes | Monocyte adhesion & cytokine release | Correlated well with literature expectations for pro-/anti-inflammatory responses [11] | Pharmaceutical and chemical screening; target identification |

| Vascular Toxicity | iPSC-derived endothelial cells with transcriptome analysis | Gene expression profiles for vascular toxicity detection | Reliable surrogate for primary vasculature; improved toxicity detection [11] | Drug testing; disease modeling; cell therapy |

| Rhythmicity (Arrhythmia) | Graphene-enabled optical stimulation of cardiomyocytes | Light-induced activation patterns & pharmacological responses | Validated reliability and reproducibility across tests [11] | Drug discovery for anti-arrhythmic therapies |

| Contractility Dysfunction | 3D engineered heart tissues (EHTs) | Reversible contractile dysfunction & hypoxia markers | Identified NAD homeostasis as crucial recovery factor [11] | Modeling tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy |

Regulatory Implementation Framework

The integration of AOPs into regulatory decision-making requires careful consideration of the Context of Use (COU). For new drug applications, defining a clear COU for in vitro models is essential, with models needing to be "simple yet sufficiently complex to address the targeted questions" [11]. Standardization of cell culture conditions and incorporation of appropriate quality controls are critical to ensure model performance, enhance reproducibility, and improve predictability in regulatory assessments.

The AOP framework facilitates this process by establishing scientifically credible links between mechanistic data and regulatory endpoints. This is particularly valuable for addressing the seven recognized cardiac failure modes: vasoactivity, contractility, rhythmicity, myocardial injury, endothelial injury, vascular injury, and valvulopathy [11]. By mapping specific AOPs to these failure modes, researchers can develop targeted testing strategies that provide mechanistically rich data to support safety assessments.

Protocol: Validating AOP-Based Assays for Regulatory Submission

Protocol Title

Comprehensive Validation of AOP-Informed In Vitro Models for Cardiac Liability Assessment

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: AOP validation workflow for regulatory submission

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Microfluidic Model for Vascular Injury Assessment

Objective: To assess drug-induced vascular injury using a human-relevant microfluidic system that addresses the vascular injury failure mode and its associated AOPs [11].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- BioFlux microphysiological system or equivalent

- Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs)

- THP-1 monocyte cell line

- Cell culture media (serum-free, chemically defined to minimize variability)

- Test compounds: reference vasoactive drugs (e.g., pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory compounds)

- Immunostaining reagents: fluorescently labeled antibodies for adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, ICAM-1)

- Cytokine detection kit (e.g., ELISA or multiplex bead array for IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1)

Procedure:

- System Setup: Prime microfluidic channels with appropriate extracellular matrix proteins (e.g., fibronectin or collagen) to mimic the vascular basement membrane.

- Cell Culture: Seed HAECs into microfluidic channels at 90-100% confluence and culture for 3-5 days under physiological shear stress (typically 10-20 dyn/cm²) to form a mature endothelial monolayer.

- Compound Exposure: Introduce test compounds across a concentration range (minimum of 5 concentrations) for 4-24 hours while maintaining flow conditions. Include positive controls (e.g., TNF-α) and negative controls (vehicle only).

- Monocyte Adhesion Assay: Introduce THP-1 monocytes into the system at a defined concentration (e.g., 1×10ⶠcells/mL) and allow to perfuse for 30-60 minutes. Quantify adhered monocytes using time-lapse imaging and automated cell counting.

- Cytokine Analysis: Collect effluent from the system and measure cytokine release using standardized immunoassays.

- Endpoint Analysis: Fix cells and perform immunostaining for endothelial adhesion markers for additional mechanistic insight.

Validation Parameters:

- Accuracy: Correlation with known literature data for reference compounds

- Precision: Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variation <20%

- Sensitivity: Ability to detect statistically significant changes at biologically relevant concentrations

- Specificity: Differentiation between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses

Protocol 2: iPSC-Derived Endothelial Cell Model for Vascular Toxicity

Objective: To predict vascular liability using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells (iPSC-ECs) and transcriptome analysis, addressing the vascular toxicity failure mode [11].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Commercially available or in-house differentiated iPSC-ECs

- Defined endothelial cell culture media (avoiding fetal bovine serum to ensure human-relevance)

- RNA extraction and sequencing reagents

- Reference compounds with known vascular toxicity profiles

- High-content imaging system for morphological assessment

- Tubule formation assay reagents (e.g., Matrigel)

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Maintain iPSC-ECs in validated culture conditions ensuring preservation of endothelial markers (CD31, VE-cadherin, vWF).

- Compound Exposure: Expose cells to test compounds for 24-72 hours across a concentration range. Include appropriate controls.

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Extract RNA and perform RNA sequencing. Focus on established vascular toxicity signatures and pathway analysis.

- Functional Validation: Perform complementary functional assays:

- Tubule Formation Assay: Assess angiogenic capability on Matrigel

- Permeability Assay: Measure endothelial barrier function using dextran flux or TEER

- Surface Marker Expression: Quantify endothelial adhesion molecules by flow cytometry

- Data Integration: Correlate transcriptomic changes with functional outcomes to establish key event relationships.

Analytical Methods:

- Bioinformatics: Pathway enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG, Reactome)

- Benchmarking: Compare gene expression profiles to known vascular toxicants

- Dose-Response Modeling: Calculate benchmark concentrations for transcriptional changes

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AOP-Informed Toxicity Testing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in AOP Testing | Considerations for Regulatory Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Sources | iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes/endothelial cells; Primary human cells | Provide human-relevant biological context for key events | Standardized differentiation protocols; Quality control for batch-to-batch variation [11] |

| Microphysiological Systems | BioFlux; Organ-on-chip platforms | Mimic tissue-level complexity and mechanical forces | Demonstration of physiological relevance; Reproducibility across laboratories [10] |

| Detection Reagents | RNA sequencing kits; High-content imaging probes; ELISA kits | Quantify molecular and cellular key events | Analytical validation; Minimum performance standards [11] |

| Chemically Defined Media | Serum-free cell culture media formulations | Reduce variability and improve reproducibility | Elimination of animal-derived components; Composition transparency [10] |

Data Analysis and Regulatory Documentation

Statistical Analysis Plan

- Dose-Response Modeling: Fit data using appropriate models (e.g., Hill slope, PROAST) to derive point of departure estimates

- Benchmark Concentration (BMC) Analysis: Calculate BMC for each key event using standardized approaches

- Uncertainty Assessment: Quantify biological and technical variability through replicate experiments (minimum n=3 independent experiments)

AOP Network Integration

The relationship between molecular initiating events, key events, and adverse outcomes can be visualized through the following AOP framework:

Diagram 2: AOP framework linking molecular events to adverse outcomes

Regulatory Submission Package

For successful regulatory acceptance, include the following elements in the validation dossier:

- Context of Use Statement: Explicit description of the intended purpose and limitations of the AOP-informed assay

- Standard Operating Procedures: Detailed protocols with quality control criteria

- Reference Compound Data: Results from compounds with known human effects

- Cross-laboratory Validation Data: When available, data demonstrating reproducibility

- Uncertainty Characterization: Assessment of false positive/negative rates and variability sources

The integration of AOPs into 21st century toxicology represents a fundamental advancement in how we approach chemical safety assessment. By providing a structured framework that links mechanistic data to adverse outcomes, AOPs enable more predictive, human-relevant safety testing while addressing the regulatory need for reduced animal testing. The protocols and application notes detailed herein provide a roadmap for researchers to develop robust, AOP-informed testing strategies that can generate regulatory-grade data, ultimately supporting safer drug development and more efficient regulatory decision-making.

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework serves as a knowledge assembly and translation tool designed to support the interpretation of pathway-specific mechanistic data for regulatory risk assessment [12]. An AOP describes a sequential chain of causally linked events at different levels of biological organization, beginning with a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) where a chemical stressor directly interacts with a biological target, and progressing through measurable Key Events (KEs) at cellular, tissue, and organ levels, ultimately culminating in an Adverse Outcome (AO) relevant to regulatory decision-making [8] [9]. This conceptual framework directly addresses the critical challenge in modern toxicology of translating data from non-animal New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)—including in silico models and in vitro assays—into predictions of apical adverse effects traditionally obtained from whole animal studies [13] [12].

The AOP framework is chemically agnostic, meaning it captures response-response relationships resulting from a specific perturbation that could be caused by numerous chemical or non-chemical stressors [12]. This property makes AOPs particularly valuable for addressing regulatory mandates requiring assessment of vast numbers of chemicals, as seen in programs such as the European Union's REACH and the revised Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) in the United States [12]. By providing a structured approach to organize mechanistic information, AOPs facilitate the use of data streams often not employed in traditional risk assessment, thereby increasing the capacity and efficiency of safety assessments for both single chemicals and chemical mixtures [12].

AOP Conceptual Foundation and Key Principles

The "Biological Dominos" Concept

The AOP framework can be visualized as a series of "biological dominos" [8] [9]. In this analogy, a stressor triggers a molecular interaction (the MIE), which represents the first biological domino. If this initial interaction is sufficiently substantial, it causes additional biological dominos to fall, with each domino representing a Key Event at increasing levels of biological organization (from cells to tissues to organs) [8]. The final domino in the sequence represents the Adverse Outcome, which is a health effect such as tumor formation or reproductive impairment that is considered relevant for risk assessment or regulatory decision making [8].

Each KE in the sequence is considered "essential," meaning that if it does not occur (the domino does not fall), then none of the downstream KEs in the pathway will occur [8]. The relationships between these dominos are described through Key Event Relationships (KERs), which articulate how a particular biological change triggers the next event in the sequence [8]. These KERs are defined based on three types of evidence: biological plausibility (existing biological knowledge supports the relationship), empirical support (experimental evidence that KE1 causes KE2), and quantitative understanding (the conditions under which a change in KE1 will cause a change in KE2) [8].

Essential AOP Terminology and Definitions

- Molecular Initiating Event (MIE): The initial point of chemical interaction with a biomolecule within an organism, such as a chemical binding to a specific receptor or inhibiting an enzyme [8] [9].

- Key Event (KE): A measurable change in biological state at various levels of organization (cellular, tissue, organ) that is essential for progression to the Adverse Outcome [8] [9].

- Key Event Relationship (KER): A documented causal relationship between two Key Events that describes the evidence supporting how one event leads to another [8].

- Adverse Outcome (AO): An adverse effect at the individual level (e.g., reduced survival, impaired reproduction) or population level that is relevant for regulatory decision-making [8] [9].

- Stressor: A chemical, biological, or physical agent that can interact with a biological system to initiate an AOP (e.g., chemical, nanomaterial, radiation, virus) [8].

- AOP Network: Multiple AOPs linked through shared KEs that more accurately represent biological complexity and multi-stressor impacts [8] [9].

AOP Development Workflow and Data Integration

The development of a scientifically credible AOP follows a systematic workflow that integrates evidence from multiple sources and employs standardized evaluation methods. The diagram below illustrates this iterative process from problem formulation through to regulatory application.

Problem Formulation and Evidence Collection

The AOP development process begins with problem formulation to define the regulatory or biological context, the scope of the AOP, and the specific Adverse Outcome of interest [14]. This is followed by comprehensive evidence collection through systematic literature reviews, data mining of existing toxicological databases, and generation of new experimental data using appropriate NAMs [14]. For example, in developing an AOP for decreased ALDH1A activity leading to decreased fertility, an initial scoping search of open literature was performed using pre-set search terms, yielding 97 relevant publications that were systematically evaluated [14]. Evidence can be gathered from multiple streams, including in vivo studies, in vitro assays, in silico models, and high-throughput screening data.

AOP Assembly and Weight-of-Evidence Evaluation

Once evidence is collected, the AOP is assembled by identifying candidate Key Events and establishing plausible causal linkages between them [14]. Each proposed KER then undergoes rigorous Weight-of-Evidence (WoE) evaluation using modified Bradford Hill considerations to assess biological plausibility, essentiality, empirical support, and consistency [12]. This evaluation determines the confidence in the overall AOP and identifies critical knowledge gaps. The AOP is formally documented in structured formats, primarily the AOP-Wiki [13] [9], which serves as an interactive knowledge base for describing, displaying, and archiving AOPs in accordance with international guidance and templates [12].

Quantitative AOP Development and Application

While qualitative AOPs provide valuable conceptual frameworks, Quantitative AOPs (qAOPs) incorporate mathematical relationships that describe the dynamics and dependencies between KEs, enabling prediction of the conditions under which the AO will occur [12]. For example, Conolly et al. described a qAOP that utilizes a feedback-controlled hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis model to enable predictions of reproductive capacity in fish exposed to chemicals that inhibit sex steroid synthesis [12]. These quantitative models facilitate the definition of perturbation thresholds and response magnitudes necessary for pathway progression, thereby strengthening the utility of AOPs for predictive toxicology and risk assessment [12].

Experimental Protocols for AOP Development and Application

Protocol 1:In VitroReceptor Binding Assays for MIE Identification

Purpose: To identify Molecular Initiating Events by screening chemical interactions with key biological receptors.

Background: This protocol was utilized in a case study investigating OTNE-induced thyroid effects, where receptor ligand-binding assays identified CAR, FXR, and PXR activation as MIEs, with thyroid perturbation occurring as secondary effects [15].

Materials:

- Human, mouse, and/or rat nuclear receptor constructs

- Test chemical (e.g., OTNE for fragrance ingredient assessment)

- Positive control ligands for each receptor

- Cell culture materials (appropriate cell lines, culture media, etc.)

- Reporter gene assay components (luciferase, β-galactosidase)

- Detection instrumentation (luminescence/fluorescence plate reader)

Procedure:

- Transient Transfection: Transfect appropriate host cells with nuclear receptor plasmids (CAR, FXR, LXRα, PPARα/δ/γ, PXR, AhR) and reporter constructs.

- Chemical Exposure: Treat transfected cells with test chemical across a range of concentrations (typically 0.1 nM - 100 μM) for 24-48 hours.

- Control Setup: Include vehicle controls and receptor-specific positive controls for each experiment.

- Response Measurement: Quantify receptor activation using reporter gene assays (e.g., luciferase activity).

- Data Analysis: Calculate fold activation relative to vehicle control and determine EC50 values for receptor activation.

- Result Interpretation: Classify chemicals as activators based on statistically significant response thresholds (typically >2-fold activation at non-cytotoxic concentrations).

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Include cytotoxicity assessments to ensure responses are not due to general toxicity

- Verify receptor specificity through antagonist studies when novel activators are identified

- Consider species differences in receptor activation profiles

Protocol 2: High-Content Imaging for Key Event Assessment

Purpose: To quantitatively measure intermediate Key Events using automated image analysis.

Background: This approach enables collection of multiparameter data from in vitro systems that can be mapped to specific KEs within an AOP, such as changes in cell morphology, proliferation, or specific pathway activation.

Materials:

- High-content imaging system (e.g., ImageXpress, Operetta, or CellInsight)

- Cell lines relevant to the AOP (primary cells or appropriate cell models)

- Multiplexed fluorescent dyes or antibodies (nuclear stains, cytotoxicity markers, specific protein markers)

- Multi-well plates (96-well or 384-well format)

- Automated liquid handling systems for consistent compound dosing

Procedure:

- Experimental Setup: Plate cells in multi-well plates at optimized densities and allow attachment for 24 hours.

- Chemical Treatment: Expose cells to test compounds across concentration ranges using automated liquid handling.

- Staining and Fixation: At appropriate timepoints, fix cells and stain with multiplexed marker panels relevant to KEs.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire images across multiple fields and channels using automated high-content imaging systems.

- Image Analysis: Use automated algorithms to quantify relevant parameters (cell count, morphology, fluorescence intensity, spatial relationships).

- Data Integration: Correlate multiparameter responses across concentration ranges to establish KE response patterns.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Optimize cell density and imaging parameters for each cell type

- Include quality control checks for focus, staining consistency, and cell health

- Validate automated analysis algorithms with manual scoring for initial setup

Application Case Studies in Regulatory Contexts

Case Study 1: AOP-Based Assessment of Thyroid Perturbation

A comprehensive case study demonstrates the application of the AOP framework to investigate thyroid effects induced by the synthetic fragrance ingredient Octahydro-tetramethyl-naphthalenyl-ethanone (OTNE) [15]. Traditional toxicological studies had identified OTNE target organs as the liver and skin via oral and dermal routes, with observed effects on thyroid and thyroid hormones suggesting perturbation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis [15].

Investigation Approach: Researchers employed NAMs to identify MIEs using in vitro receptor ligand-binding assays for multiple nuclear receptors including CAR, FXR, LXRα, PPARs, PXR, and AhR [15]. The data generated informed an AOP network where CAR, FXR, and PXR activation served as MIEs, with thyroid perturbation occurring as secondary effects [15].

Regulatory Impact: This AOP-informed analysis demonstrated that the observed thyroid effects were secondary to liver effects, leading to the important regulatory conclusion that "thyroid effects should not be the basis for assessing potential OTNE-induced human health hazards" [15]. This case exemplifies how AOP networks can clarify primary versus secondary toxicity mechanisms, preventing potentially misleading regulatory decisions based on downstream effects that may not represent the primary hazard.

Case Study 2: Skin Sensitization AOP for Animal-Free Testing

The skin sensitization AOP represents one of the most developed and regulatory accepted applications of the AOP framework [12]. This AOP includes description of several intermediate KEs related to covalent binding to skin proteins (MIE), induction of inflammatory cytokines, and proliferation of T-cells [12].

Regulatory Context: Legislation in the European Union dictated moving away from whole animal tests for evaluating sensitization, creating an urgent need for alternative assessment approaches [12].

AOP Solution: The well-defined AOP for skin sensitization provided the basis for identifying and validating a suite of in vitro assays reflecting these intermediate KEs [12]. Data from this assay suite for test chemicals can be assessed using modeling approaches such as Bayesian network analysis to combine/weight data from different biological levels of organization to produce categorical predictions of skin sensitization potential [12].

Impact: This AOP-based approach demonstrates how pathway understanding can facilitate the use of alternative data streams as a complete replacement for conventional test methods, supporting both animal welfare and more mechanistically informed safety decisions [12].

Quantitative Data Integration in AOPs

Table 1: Experimentally-Derated ECâ‚…â‚€ Values for Nuclear Receptor Activation

| Nuclear Receptor | Test System | Positive Control (ECâ‚…â‚€) | OTNE (ECâ‚…â‚€) | Key Event in AOP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutive Androstane Receptor (CAR) | Reporter assay (HEK293T) | CITCO (0.6 ± 0.2 μM) | 3.2 ± 0.8 μM | Molecular Initiating Event |

| Pregnane X Receptor (PXR) | Reporter assay (HepG2) | Rifampicin (0.8 ± 0.3 μM) | 5.1 ± 1.2 μM | Molecular Initiating Event |

| Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) | Reporter assay (HEK293T) | GW4064 (0.015 ± 0.005 μM) | 12.4 ± 2.5 μM | Molecular Initiating Event |

| Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ (PPARγ) | Reporter assay (3T3-L1) | Rosiglitazone (0.04 ± 0.01 μM) | >25 μM | Not Activated |

Table 2: Key Event Relationships in the ALDH1A Inhibition AOP

| Key Event Relationship | Biological Plausibility | Empirical Support | Quantitative Understanding | Evidence Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased ALDH1A activity → Decreased atRA concentration | Strong (direct biochemical relationship) | Strong (genetic and chemical inhibition studies) | Strong (kinetic models available) | [14] |

| Decreased atRA concentration → Disrupted meiotic initiation | Strong (atRA is meiosis-inducing signal) | Strong (mouse genetic models and RA pathway inhibition) | Moderate (concentration thresholds established) | [14] |

| Disrupted meiotic initiation → Decreased ovarian reserve | Strong (all oocytes formed during development) | Strong (mouse and human observational studies) | Moderate (dose-response relationship) | [14] |

| Decreased ovarian reserve → Decreased fertility | Strong (established reproductive biology) | Strong (human fertility studies) | Strong (quantitative relationship established) | [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for AOP Development

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Application in AOP Development | Regulatory Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Receptor Assay Systems | CAR, FXR, LXRα, PPARs, PXR, AhR reporter assays [15] | Identification of Molecular Initiating Events | Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program [9] |

| High-Content Screening Platforms | Automated image analysis, multiparameter cytotoxicity assessment | Quantitative Key Event measurement | Prioritization of chemicals for targeted testing [8] |

| Transcriptomic Technologies | RNA-seq, targeted gene expression panels | Pathway perturbation assessment | Building confidence in NAMs for neurotoxicity [9] |

| AOP Knowledge Management | AOP-Wiki [13], AOP-KB | Collaborative AOP development and dissemination | International harmonization (OECD) [13] |

| Cross-Species Extrapolation Tools | SeqAPASS [8] | Evaluating conservation of KEs across species | Ecological risk assessment [8] |

| Broussochalcone A | Broussochalcone A, CAS:99217-68-2, MF:C20H20O5, MW:340.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Nanaomycin D | Nanaomycin D|Antibiotic Quinone|Research Grade | Nanaomycin D is a quinone antibiotic that induces superoxide radical production in bacterial research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

AOP Networks and Complex Biology

Individual AOPs represent deliberate simplifications of biological complexity to enhance utility for specific applications. However, biological systems involve extensive crosstalk between pathways, which can be captured through AOP networks [12] [8]. These networks consist of multiple AOPs linked by shared KEs and KERs, providing a more realistic representation of biological complexity [8]. The diagram below illustrates how multiple stressors can converge on shared Key Events, leading to various Adverse Outcomes through interconnected pathways.

The functional unit of prediction for real-world application is the AOP network rather than individual AOPs [8]. For example, in the OTNE case study, an AOP network revealed how activation of multiple receptors (CAR, FXR, PXR) converged on thyroid perturbation as a shared intermediate event [15]. This network perspective is particularly valuable for understanding mixture effects, as chemicals with different MIEs may share common intermediate KEs, leading to potential additive or synergistic effects [8]. The US EPA emphasizes that "AOP networks are the functional unit of prediction" as they better capture the complexity of real biological systems [8].

Regulatory Implementation and Future Directions

Building Confidence in New Approach Methodologies

AOPs play a critical role in building scientific confidence for the use of NAMs in regulatory decision-making [9]. By establishing mechanistic connections between in vitro perturbations and in vivo outcomes, AOPs provide the biological context needed to interpret NAMs data for risk assessment purposes [8]. For instance, EPA researchers are developing AOPs to build confidence in using in vitro NAMs data to predict adverse outcomes on brain development and function (developmental neurotoxicity) [9]. Similarly, AOPs are being used to develop in vitro methods for more rapid identification of chemicals that cause tumors in rats, building confidence in using these alternative methods to identify carcinogenic chemicals with less reliance on animal testing [9].

FAIR Data Principles and AOP Standardization

Current international efforts focus on making AOP data align with FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) metadata standards [13]. This relies on technical tools that implement and process AOP data and related metadata, along with establishing coordinated computational bioinformatic methods [13]. The "FAIR AOP roadmap for 2025" addresses the FAIRification of AOP mechanistic data and metadata, as well as international collaborative efforts to document and improve the (re)-use and reliability of AOP information [13]. These coordinated efforts contribute to establishing a directive for processing and storing standardized AOP mechanistic data in the AOP-Wiki repository and applying these data to next generation risk assessment [13].

Quantitative AOPs and Cross-Species Extrapolation

Future directions in AOP development include expanding the development of quantitative AOPs (qAOPs) that incorporate computational models to describe quantitative relationships between KEs [12]. These models enable prediction of the conditions under which perturbation of an upstream KE will lead to progression through the pathway to the AO [12]. Additionally, AOPs are increasingly being used to address uncertainties in cross-species extrapolation for both human health and ecological risk assessment [8]. By evaluating the conservation of KEs and KERs across species, AOPs can support extrapolation of toxicity data from tested to untested species, addressing a significant uncertainty in chemical risk assessment [8]. Tools such as the EPA's SeqAPASS can support these assessments by evaluating the structural conservation of molecular targets across species [8].

Core Terminology and Definitions

In Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) development, four terms form the conceptual backbone: Molecular Initiating Event (MIE), Key Event (KE), Key Event Relationship (KER), and Adverse Outcome (AO). The table below defines these essential components.

Table 1: Essential AOP Terminology and Definitions

| Term | Acronym | Definition | Role in the AOP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Initiating Event | MIE | The initial point of chemical interaction with a biomolecule within an organism, creating a perturbation that starts the AOP [8] [16]. | Anchors the upstream end of the AOP; the first biological "domino" [8]. |

| Key Event | KE | A measurable change in biological state that is essential for the progression from the MIE toward the Adverse Outcome [8] [6] [16]. | Represents measurable "dominos" at different biological levels (cell, tissue, organ) [8]. |

| Key Event Relationship | KER | A scientifically-based, directional relationship describing the causal linkage between an upstream and a downstream Key Event [8] [6] [16]. | Defines how one KE triggers the next; the arrow connecting the dominos [8]. |

| Adverse Outcome | AO | An adverse effect at the organism or population level that is relevant to regulatory decision-making and risk assessment [8] [16]. | Anchors the downstream end of the AOP; the final domino with regulatory significance [8] [6]. |

An AOP is a conceptual framework that organizes existing knowledge about biologically plausible and empirically supported links between a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) and an Adverse Outcome (AO) via a sequence of Key Events (KEs) connected by Key Event Relationships (KERs) [6] [16] [17]. This framework is not chemical-specific but rather depicts a generalized sequence of biological effects that can be triggered by any stressor that interacts with a particular biological target defined by the MIE [8].

AOP Conceptual Framework and Visualization

The AOP framework is often likened to a series of "biological dominos" [8]. The chain reaction begins with the MIE, proceeds through essential KEs at increasing levels of biological organization, and culminates in the AO. The relationships between these events are explicitly described by KERs.

Diagram 1: The core AOP structure showing the sequence from MIE to AO.

Practical Application: AChE Inhibition Case Study

AOP 281: From MIE to AO

A practical illustration of these concepts is AOP 281, "AChE Inhibition Leading to Neurodegeneration" [4]. This AOP describes how certain chemicals can initiate a cascade of events leading to neurological damage.

Diagram 2: AOP 281 pathway showing KERs and a feedback loop.

Experimental Protocol for AOP 281

This protocol outlines the methodology for investigating Key Event Relationships in AOP 281, focusing on the link between acetylcholinesterase inhibition and subsequent neuronal effects.

Objective: To empirically test KERs within AOP 281, specifically the relationship between AChE inhibition, muscarinic receptor overactivation, and the onset of focal seizures.

Methodology:

Step 1: Literature Review & Data Extraction

- Perform a comprehensive literature search using databases (e.g., PubMed, Web of Science) with keywords: "acetylcholinesterase inhibition," "acetylcholine," "muscarinic receptor," "seizures," "excitotoxicity," "neurodegeneration."

- Screen over 200 research papers for relevance [4].

- Extract and categorize quantitative data suitable for model development, prioritizing studies that measure multiple adjacent Key Events (e.g., AChE activity and acetylcholine levels, or receptor activation and seizure activity) [4].

Step 2: In Vitro & In Vivo Experimental Validation

- In Vitro Model: Apply an AChE inhibitor (e.g., chlorpyrifos oxon) to neuronal cell cultures or brain slice preparations.

- In Vivo Model: Administer AChE inhibitors (e.g., organophosphate pesticides) to laboratory rodents at varying doses.

- Measurements:

- MIE/KE1: Quantify AChE activity (Ellman assay) and synaptic acetylcholine levels (microdialysis/HPLC) [4].

- KE2: Assess muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR) activation (calcium imaging, electrophysiology).

- KE3/KE7: Monitor and quantify seizure activity (electroencephalography - EEG).

- Downstream KEs: Measure intracellular calcium (Ca²âº) flux (fluorometric assays), NMDA receptor activation, and markers of cell death (e.g., TUNEL staining, LDH release).

Step 3: Data Integration & Model Building

- Use statistical analysis to establish dose-response and temporal concordance between upstream and downstream KEs.

- Develop a quantitative AOP (qAOP) using computational approaches (e.g., systems biology modeling with ordinary differential equations or a Bayesian Network) to mathematically define the KERs [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for AOP 281 Investigation

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| AChE Inhibitors (e.g., organophosphates) | Chemical stressors used to trigger the Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) in experimental models. |

| Ellman Assay Kit | A standard biochemical method for quantifying acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity to confirm the MIE. |

| Microdialysis System | For sampling and measuring dynamic changes in synaptic acetylcholine (ACh) levels in vivo (KE1). |

| Primary Neuronal Cultures | In vitro system for mechanistic studies of receptor activation and early cellular Key Events. |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | Critical equipment for monitoring and quantifying focal seizures and status epilepticus in vivo (KE3, KE7). |

| Calcium-Sensitive Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Fura-2) | Used in fluorometric assays and live-cell imaging to measure elevated intracellular calcium (KE6). |

| Bayesian Network Software (e.g., Bayesian tools in R/Python) | Computational tool for building quantitative, probabilistic models of the AOP network. |

| 1-Propene, 1-(methylthio)-, (Z)- | 1-Propene, 1-(methylthio)-, (Z)-, CAS:52195-40-1, MF:C4H8S, MW:88.17 g/mol |

| Isobellidifolin | Isobellidifolin|High-Purity|For Research Use Only |

Quantitative AOPs (qAOPs) and Data Analysis

The transition from a qualitative AOP to a Quantitative AOP (qAOP) is a critical step for predictive toxicology. A qAOP is a mathematical representation of the KERs within an AOP, which allows for the prediction of whether, and under what conditions, a perturbation will lead to the Adverse Outcome [4] [18].

Table 3: Common Approaches for Quantitative AOP (qAOP) Development

| Modeling Approach | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Response-Response Relationships | Fitting mathematical functions (e.g., regression) to experimental data linking two adjacent Key Events [4]. | Modeling the quantitative relationship between the level of AChE inhibition and the magnitude of synaptic ACh increase. |

| Biologically-Based Mathematical Modeling | Using systems of ordinary differential equations to represent the underlying biology and dynamics of the pathway [4]. | Modeling the kinetics of receptor activation, neurotransmitter release, and calcium signaling in AOP 281. |

| Bayesian Networks (BN) | A probabilistic graphical model where nodes represent KEs and edges represent conditional dependencies. Useful for complex AOPs with uncertainty [4]. | Modeling the entire AOP 281 network to predict the probability of neurodegeneration given a certain degree of AChE inhibition, accounting for data gaps. |

Key challenges in qAOP development highlighted by case studies like AOP 281 include the scarcity of studies that measure multiple KEs simultaneously, difficulties in data extraction from literature, and ensuring model transferability across different platforms and species [4].

AOP Development in Action: Methodologies, Tools, and Real-World Applications

The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework is a conceptual construct that organizes existing knowledge concerning biologically plausible and empirically supported links between a molecular-level perturbation and an adverse outcome of regulatory relevance [6] [19]. An AOP describes a sequential chain of causally linked events at different levels of biological organisation, leading to an adverse health or ecotoxicological effect [7]. Systematic development of AOPs is critical for improving regulatory decision-making through greater integration and more meaningful use of mechanistic data [6].

AOPs are built upon two fundamental modular components: Key Events (KEs), which are measurable changes in biological state that are essential for progression toward an adverse outcome, and Key Event Relationships (KERs), which define the causal linkages between pairs of KEs [6] [19]. The AOP begins with a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE), representing the initial interaction between a stressor and a biological target, and culminates in an Adverse Outcome (AO) relevant to risk assessment [9] [19].

The development of AOPs is guided by five core principles: (1) AOPs are not chemical-specific; (2) AOPs are modular and composed of reusable components; (3) an individual AOP is a pragmatic unit of development; (4) networks of multiple AOPs are the functional unit of prediction for real-world scenarios; and (5) AOPs are living documents that evolve as new knowledge emerges [6] [19] [8].

AOP Development Strategic Approaches

AOP development can be initiated through different strategic approaches depending on the available knowledge and research objectives. The three primary strategies include top-down, bottom-up, and middle-out approaches, each with distinct starting points and applications [19] [20].

Table 1: Comparison of AOP Development Strategic Approaches

| Development Strategy | Starting Point | Application Context | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Down | Adverse Outcome (AO) | Well-characterized adverse outcomes with unknown initiating mechanisms | Anchors development to regulatory relevance; identifies knowledge gaps in upstream events |

| Bottom-Up | Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) | Mechanistic understanding of molecular interactions with unknown higher-order effects | Leverages novel molecular screening data; identifies potential hazards from early perturbations |

| Middle-Out | Intermediate Key Event (KE) | Partially characterized toxicity pathways with gaps in both upstream and downstream events | Efficient when mechanistic data exists for cellular/tissue responses but not endpoints |

| Case Study-Based | Model Chemical(s) | Data-rich chemicals used as prototypes for generalizing to other stressors | Provides concrete examples; facilitates read-across and categorization of similar chemicals |

| Data-Mining | High-Throughput/High-Content Data | Large datasets (e.g., omics) available for identifying KEs and inferring linkages | Data-driven discovery; enables identification of novel pathways and connections |

Top-Down Development Strategy

The top-down approach begins with a well-characterized adverse outcome at the organism or population level and works backward to identify preceding key events and molecular initiating events [19]. This strategy is particularly valuable when the adverse effect is well-established in traditional toxicology but the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood.

Protocol 1: Top-Down AOP Development Workflow

- Define the Adverse Outcome: Clearly specify the AO at the organism or population level that has regulatory relevance. Example: growth impairment in fish [21].

- Identify Immediate Precursor Events: Determine the tissue or organ-level responses that directly lead to the AO.

- Trace Biological Cascades Backward: Systematically identify cellular and molecular events preceding the tissue/organ responses.

- Establish Causal Relationships: For each pair of adjacent KEs, collect evidence supporting a causal relationship (biological plausibility, empirical evidence).

- Define Molecular Initiating Event: Identify the initial molecular interaction that triggers the cascade.

- Assess Essentiality of Each KE: Evaluate whether each KE is necessary for the progression to the AO.