A Modern Methodology: Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment for Informed Decision-Making

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment (LERA) methodology, tailored for researchers and professionals in environmental science and planning.

A Modern Methodology: Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment for Informed Decision-Making

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment (LERA) methodology, tailored for researchers and professionals in environmental science and planning. It begins by exploring the foundational principles and core concepts that define the field, from risk frameworks to spatial heterogeneity. The piece then details the methodological workflow, including index construction, geospatial techniques, and practical applications through major case studies. It addresses common challenges, such as subjectivity and scale dependency, and offers solutions for optimization. Finally, the article examines methods for validating assessment results and comparing different methodological approaches, concluding with a synthesis of key insights and future directions for research and application in spatial planning and ecosystem management.

Understanding the Basics: Core Concepts and Principles of Landscape Ecological Risk

Landscape Ecological Risk (LER) assessment is a methodological approach that evaluates the potential adverse effects on ecosystem structure, function, and services resulting from the interaction between landscape patterns and ecological processes under natural or anthropogenic disturbances [1]. This field has evolved from human health and contaminant-based risk assessment models to a landscape-centric framework that emphasizes spatial heterogeneity, scale effects, and the cumulative impacts of multiple stressors [2]. Within a broader thesis on LER methodology, this article delineates the transition from conceptual models to standardized application protocols, providing researchers with actionable frameworks for ecological risk characterization.

Traditional ecological risk assessment often followed a "risk source–risk receptor–risk impact" model, primarily focusing on specific environmental hazards like pollutants [3]. In contrast, LER assessment breaks from this limitation by utilizing landscape pattern indices to construct a composite risk index [3]. This approach allows for a holistic evaluation of various potential ecological threats and their cumulative, spatially explicit outcomes [3]. The core conceptual advancement lies in linking spatial patterns—such as fragmentation, connectivity, and diversity—to ecological processes and vulnerabilities [2]. A contemporary refinement integrates the supply-demand balance of ecosystem services, arguing that risk arises not only from the loss of ecological supply but also from the escalating demand from socio-economic systems [4]. Furthermore, integrating ecosystem resilience—the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and maintain function—into the LER framework is recognized as crucial for informing effective ecological management and restoration zoning [2].

Methodological Framework and Assessment Protocols

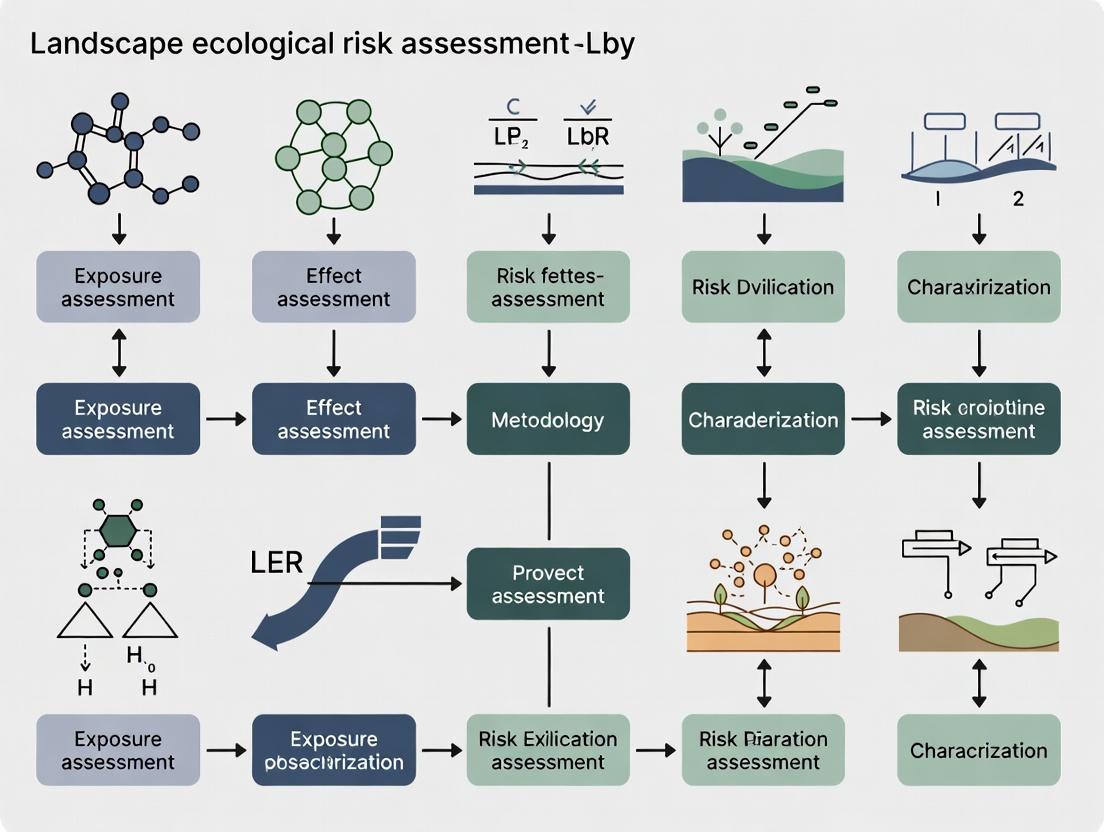

A robust LER assessment protocol involves sequential stages: landscape pattern analysis, risk index construction, spatial characterization, and driver identification. The following workflow and detailed protocols standardize this process.

Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment Core Workflow

Protocol 1: Landscape Classification and Assessment Unit Delineation

- Objective: To establish a spatially explicit foundation for risk calculation based on land use/cover or functional space.

- Procedure:

- Source Land Use Data: Utilize multi-temporal land use/cover (LULC) data with a resolution appropriate to the study scale (e.g., 30m) [5]. Classify land types (e.g., forest, cropland, urban, water).

- Alternative Functional Classification: For a socio-ecological perspective, reclassify LULC into Production-Living-Ecological Spaces (PLES) [1] [5]. For instance, assign cropland and industrial land to Production Space; rural and urban settlements to Living Space; and forests, grasslands, and water bodies to Ecological Space [5].

- Delineate Assessment Units: Overlay a regular grid (e.g., 3 km × 3 km) over the study area. The grid size should be 2–5 times the average landscape patch area to capture pattern heterogeneity [3]. For watershed studies, sub-catchments can serve as natural assessment units [2].

Protocol 2: Composite LER Index Calculation

- Objective: To compute a dimensionless LER index that integrates landscape disturbance and vulnerability.

- Procedure [3]:

- Calculate Landscape Metrics per Unit: For each assessment unit k, use software like Fragstats to calculate:

- Landscape Disturbance Index (LDIi): A weighted sum of indices for the i-th landscape type:

LDI_i = aC_i + bF_i + cD_i. WhereC_iis the fragmentation index,F_iis the fractal dimension index (measuring shape complexity), andD_iis the dominance index. Weights a, b, and c sum to 1. - Landscape Vulnerability Index (LVIi): Determine the relative susceptibility of each landscape type to external stresses. This can be assigned empirically (e.g., 1-6 for construction land to unused land) [2] or derived from ecosystem service valuation (e.g., normalized composite of water retention, soil conservation, carbon sequestration) [2]. Values are normalized to 0–1.

- Landscape Disturbance Index (LDIi): A weighted sum of indices for the i-th landscape type:

- Compute Landscape Loss Index (LLIi):

LLI_i = LDI_i × LVI_i. - Compute Final LER for Unit k:

LER_k = Σ ( (A_{ki} / A_k) × LLI_i ). WhereA_{ki}is the area of landscape i in unit k, andA_kis the total area of unit k. HigherLER_kindicates greater risk.

- Calculate Landscape Metrics per Unit: For each assessment unit k, use software like Fragstats to calculate:

Protocol 3: Spatiotemporal Analysis and Driving Force Detection

- Objective: To identify risk patterns, temporal trends, and primary causative factors.

- Procedure:

- Spatial Statistics: Perform spatial autocorrelation analysis (Global & Local Moran's I) to identify significant risk clusters (high-high, low-low) [1] [5].

- Driver Detection with GeoDetector:

- Factor Selection: Prepare raster layers of potential natural (elevation, slope, NDVI, precipitation) and anthropogenic (GDP, population density, distance to roads) drivers [3] [5].

- Discretization: Classify each continuous factor layer into appropriate intervals or strata.

- Run Factor Detector: The q-statistic quantifies the power of determinant of a factor on LER spatial heterogeneity (

q ∈ [0,1], higher value = greater explanatory power) [3]. - Run Interaction Detector: Assess whether two factors, when combined, weaken or enhance their explanatory power on LER (e.g., non-linear enhancement) [5].

Data Presentation and Quantitative Analysis

Table 1: Key LER Quantitative Findings from Regional Case Studies (2000-2020)

| Study Region | LER Trend & Magnitude | Dominant Risk Level | Key Driving Factors (q-statistic or priority) | Primary Spatial Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southwest China [4] [5] | Mean LER fluctuated ~0.20-0.21 [5]; Increased in northeast parts [4] | Medium risk zones predominant [5] | Anthropogenic disturbance & land use [5]; Shannon Diversity Index (increasing negative effect) [4] | High in northeast, low in southwest [4]; Significant clustering [5] |

| Luo River Watershed [2] | Overall LER increased (0.43 to 0.44) [2] | -- | Land use type > Elevation > Climate [2] | Lower in west, higher in east; Negative correlation with ecosystem resilience [2] |

| Lower Yangtze River [1] | Mean LER increased (0.2508 to 0.2573) [1] | Medium risk (consistently >30% area) [1] | -- | Significant positive spatial autocorrelation (Moran's I: 0.4773 to 0.4779) [1] |

| Jianghan Plain [3] | LER initially increased then decreased [3] | Medium and higher risk [3] | NDVI (primary), human activity intensity [3] | High in southeast, low in central/north [3] |

Table 2: Multi-Scenario LER Simulation for the Jianghan Plain (2030 Projection) [3]

| Scenario | Core Policy Focus | Simulated Land Use Change Trend | Projected LER Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Development | Follows historical trend | Continued cropland conversion to built-up land | Highest LER |

| Economic Development | Maximize GDP growth | Accelerated urban/industrial expansion | Higher LER |

| Cropland Protection | Protect prime farmland | Strict control of cropland loss | Lower LER |

| Ecological Protection | Prioritize ecosystem services | Expansion of woodland/grassland/water | Lowest LER |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 4: Multi-Scenario Simulation of Future LER

- Objective: To project future LER under different land use policy scenarios.

- Procedure (Markov-PLUS Model) [3]:

- Land Use Demand Projection (Markov Chain): Analyze historical transition matrices between land types. Use these probabilities to forecast the total area demand for each land type at a future date (e.g., 2030).

- Spatial Allocation (PLUS Model): Use the Land Expansion Analysis Strategy (LEAS) to mine the drivers of land type expansion. Then, apply a Cellular Automata (CA) model based on multi-class random patch seeds to allocate the projected land demands from Step 1 spatially onto the map, constrained by scenario-specific rules.

- Cropland Protection Scenario: Add conversion restrictions for prime farmland.

- Ecological Protection Scenario: Increase transition costs for developing ecological lands.

- Future LER Assessment: Calculate the LER index (Protocol 2) for the simulated future land use maps.

Multi-Scenario LER Simulation Protocol

Protocol 5: Ecological Management Zoning Based on LER and Resilience

- Objective: To delineate spatially targeted zones for adaptive ecological management.

- Procedure [2]:

- Quantify Ecosystem Resilience (ER): Construct an index from factors like vegetation net primary productivity (NPP), landscape connectivity, and soil organic matter.

- Bivariate Local Moran's I Analysis: Perform a bivariate spatial autocorrelation analysis between LER and ER values across assessment units. This identifies four types of spatial agglomeration:

- High-LER, Low-ER: Priority Ecological Restoration Region.

- Low-LER, High-ER: Core Ecological Conservation Region.

- High-LER, High-ER & Low-LER, Low-ER: Ecological Adaptation Region (requiring monitoring and adaptive management).

- Zone-Specific Strategy Formulation: Develop targeted measures for each zone (e.g., restorative projects in Restoration regions, strict protection in Conservation regions).

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LER Assessment

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application in LER Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Fragstats | Landscape pattern metric computation | Calculates core indices for the Landscape Disturbance Index (LDI) within each assessment unit [3] [5]. |

| ArcGIS / QGIS | Geospatial data processing & visualization | Used for assessment unit delineation, spatial overlay, interpolation, zoning, and map production [3] [5]. |

| GeoDetector | Spatial heterogeneity & driving force analysis | Quantifies the explanatory power (q-statistic) of individual factors and their interactions on LER spatial patterns [3] [5]. |

| Markov-PLUS Model | Land use change simulation | Projects future land use under different scenarios, forming the basis for future LER projection [3]. |

| R / Python (GDAL, scikit-learn) | Statistical analysis & machine learning | Supports advanced spatial statistics (Moran's I), regression modeling (GTWR), and Random Forest analysis for driver detection [4] [5]. |

| InVEST / RUSLE | Ecosystem service modeling | Generates quantitative maps of services (water yield, soil conservation) used to derive objective Landscape Vulnerability Indices [2]. |

| Thalidomide-5-(PEG2-amine) | Thalidomide-5-(PEG2-amine), MF:C20H24N4O7, MW:432.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Monoisodecyl Phthalate-d4 | Monoisodecyl Phthalate-d4, MF:C18H26O4, MW:310.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The discipline of ecological risk assessment (ERA) has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from a focus on human health and chemical toxicology to a comprehensive, spatially explicit analysis of landscape-scale systems [2] [6]. This evolution reflects a growing recognition that environmental management requires an understanding of complex interactions across entire ecosystems. The foundational framework, established by agencies like the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), initially emphasized a stressors-receptor model to evaluate the likelihood of adverse effects from specific hazards [7] [6]. This approach excelled at site-specific contamination issues but struggled to characterize cumulative risks from multiple, diffuse pressures across heterogeneous landscapes [2].

The shift towards Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment (LER) represents a paradigm change. LER is defined as the potential damage to an ecosystem’s structure, function, and stability within a landscape resulting from natural or anthropogenic activities [2] [7]. Unlike its predecessor, LER explicitly incorporates spatial heterogeneity, scale dependency, and the mutual feedback between landscape patterns and ecological processes [2]. It moves beyond evaluating single stressors to assess the integrated risk arising from land use change, habitat fragmentation, and climate variation, treating the landscape pattern itself as both an indicator and a mediator of risk [7] [5]. This methodological progression provides the critical tools needed to support territorial spatial ecological restoration, sustainable land management, and the achievement of global biodiversity and development goals [2] [7].

Methodological Evolution and Optimization in LER

The optimization of LER methodologies centers on overcoming the subjectivity of traditional models and enhancing their functional relevance for ecosystem management [2]. Early LER models often relied on static landscape pattern indices and expert-based assignment of vulnerability scores to different land use types, which introduced uncertainty and failed to capture dynamic ecological functions [2].

Integrating Ecosystem Services and Resilience

A significant advancement is the incorporation of ecosystem services (ES) directly into the risk assessment framework. Instead of using arbitrary vulnerability indices, modern approaches quantify landscape vulnerability based on the capacity of ecosystems to provide key services such as water conservation, soil retention, and carbon sequestration [2]. The underlying principle is that a decline in ecosystem services indicates increased landscape vulnerability and, consequently, higher ecological risk. This method provides a more scientific and ecologically meaningful assessment [2].

Concurrently, the concept of ecosystem resilience (ER) has been integrated to inform risk management. Resilience refers to an ecosystem's ability to withstand disturbance and recover its structure and function [2]. Research shows an inverse, non-linear relationship between LER and ER; improving ecosystem resilience is a proven strategy for mitigating landscape ecological risk [2]. The coupling of LER and ER assessments enables more nuanced ecological management zoning, identifying regions for priority conservation, targeted restoration, or adaptive management [2].

Analytical Workflow for Integrated LER Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for a contemporary LER assessment that incorporates ecosystem services and resilience, moving from data preparation to management guidance.

Diagram: Integrated LER Assessment Workflow Incorporating ES and Resilience [2].

Quantitative LER Findings from Case Studies

The application of these optimized methods across diverse regions reveals clear spatiotemporal patterns and driving forces of ecological risk.

Table 1: Comparative LER Assessment Findings from Regional Case Studies

| Study Region | Time Period | Overall LER Trend | Spatial Pattern | Key Driving Factors Identified | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luo River Watershed (Qinling Mountains) | 2001-2021 | Increased (0.43 to 0.44) | Lower in west, higher in east. Inverse correlation with Ecosystem Resilience. | Land use type, elevation, climate. | [2] |

| Harbin City (Northeast China) | 2000-2020 | Decreased | "High in west & north, low in east & south". High-risk areas concentrated near water bodies. | DEM (topography), interaction of DEM & precipitation. | [7] |

| Southwest China (Karst Region) | 2000-2020 | Stable (Avg. ERI 0.20-0.21) | Transition from high/low risk to medium-risk zones. Poor connectivity in northeast. | Anthropogenic disturbance, land use level, economic factors. | [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for LER Research

Protocol 1: Ecosystem Services-Based Vulnerability Assessment

This protocol details the method for replacing subjective vulnerability indices with a quantitative assessment based on ecosystem services [2].

- Objective: To calculate a spatially explicit Landscape Vulnerability Index (LVI) derived from the capacity of key ecosystem services.

- Materials: Land use/cover maps, digital elevation model (DEM), climate data (precipitation, temperature), soil type maps, and geospatial software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS with InVEST model).

- Procedure:

- Service Selection & Modeling: Identify 3-4 dominant regional ecosystem services (e.g., water yield, soil retention, carbon storage, habitat quality). Utilize biophysical models (e.g., the InVEST suite) to quantify the provision of each service for every landscape parcel or grid cell.

- Normalization & Integration: Normalize the values of each ecosystem service layer to a 0-1 scale. Use an analytic hierarchy process (AHP) or equal weighting to combine the normalized layers into a composite Ecosystem Service Capacity (ESC) index.

- Vulnerability Calculation: Invert the ESC index to derive the LVI:

LVI = 1 - ESC. This operationalizes the principle that lower service capacity equates to higher vulnerability. - Validation: Cross-validate the LVI spatial pattern with independent indicators of ecological degradation, such as soil erosion rates or habitat fragmentation indices.

Protocol 2: Multi-Scenario Future LER Simulation Using the PLUS Model

This protocol outlines steps for projecting future LER under different land-use scenarios to inform proactive management [7].

- Objective: To simulate land use change and assess consequent LER patterns for 2030 under Natural Development, Economic Priority, and Ecological Priority scenarios.

- Materials: Historical land use maps (e.g., 2000, 2010, 2020), spatial driver data (DEM, slope, distance to roads/rivers, population, GDP), the PLUS model software, and Fragstats.

- Procedure:

- Driver Analysis & Model Calibration: Use the land expansion analysis strategy (LEAS) module in PLUS to analyze the contributions of various drivers to historical land use changes. Train the multi-type random patch seed (CARS) module with historical data to calibrate simulation parameters.

- Scenario Definition:

- Natural Development: Project trends using Markov chains based on historical transition probabilities.

- Economic Priority: Increase transition probabilities to construction land, relaxing constraints near urban centers.

- Ecological Priority: Impose strict conversion restrictions on ecological lands (forest, grassland, water) and incentivize restoration.

- Land Use Simulation: Run the PLUS model for each 2030 scenario to generate projected land use maps.

- Future LER Assessment: Calculate landscape pattern indices and the LER index for each simulated map. Compare the area and spatial distribution of high-risk zones across scenarios to evaluate policy outcomes.

Protocol 3: Ecological Network Construction for Risk Mitigation

This protocol describes constructing an ecological network to enhance landscape connectivity and reduce risk by facilitating ecological flows [5].

- Objective: To identify ecological sources, corridors, and nodes to form a functional network that mitigates landscape fragmentation and ecological risk.

- Materials: LER assessment results, land use map, NDVI data, resistance surface template.

- Procedure:

- Identify Ecological Sources: Extract areas with low ecological risk (e.g., lowest 20% of ERI values) and high ecosystem service value as primary ecological source patches.

- Create Resistance Surface: Assign a cost value (1-100) to each land use type based on its permeability to species movement and ecological processes. Higher LER values should correspond to higher resistance.

- Extract Corridors and Nodes: Use the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model to calculate the least-cost paths between source patches. These paths form potential ecological corridors. Identify strategic locations where multiple corridors intersect as key ecological nodes.

- Network Analysis & Optimization: Evaluate network connectivity using metrics like corridor pinch points and node importance. Propose specific measures for protecting identified corridors (e.g., greenways) and strengthening nodes (e.g., targeted restoration).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for LER Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment

| Item Category | Specific Item / Tool | Function in LER Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Geospatial Data | Multi-temporal Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Data | Serves as the fundamental input for calculating landscape pattern indices and tracking change. | Resolution (e.g., 30m), classification accuracy, and temporal consistency are critical [2] [5]. |

| Environmental Drivers | Digital Elevation Model (DEM), Climate Datasets, Soil Maps | Used to model ecosystem services, create resistance surfaces, and analyze risk drivers via Geodetector. | Spatial resolution and accuracy directly influence model outputs like soil erosion and water yield [2] [7]. |

| Socio-economic Data | Population Density, GDP, Road Networks, Point of Interest (POI) | Quantifies anthropogenic pressure, a primary driver of land use change and ecological risk. | Temporal alignment with LULC data is necessary for robust causal analysis [7] [5]. |

| Primary Software Tools | Fragstats | The standard software for computing a wide array of landscape pattern metrics (patch, class, landscape level). | Choice of metrics must be hypothesis-driven to avoid redundancy [5]. |

| Geodetector (q-statistic) | Statistically quantifies spatial stratified heterogeneity and identifies the power of determinant factors (q) and their interactions. | Handles both numerical and categorical data well, with no linear assumption required [7] [5]. | |

| InVEST Model Suite | Integrates biophysical data to map and value ecosystem services, enabling vulnerability assessment. | Model selection and parameterization must be tailored to the study region [2]. | |

| Modeling & Simulation | PLUS Model | Simulates future land use change under multiple scenarios by coupling LEAS and CARS modules. | Superior to earlier models (CA-Markov, FLUS) in simulating patch-level changes and driver interactions [7]. |

| Validation & Analysis | Random Forest (RF) Model | A machine learning algorithm used to rank the importance of driving factors and predict risk patterns. | Provides robust, non-parametric analysis of complex variable relationships [5]. |

| TAT-HA2 Fusion Peptide | TAT-HA2 Fusion Peptide|Cell-Penetrating Reagent | TAT-HA2 Fusion Peptide enhances macromolecular delivery via endosomal escape. For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Glucocorticoids receptor agonist 2 | Glucocorticoids receptor agonist 2, MF:C25H25FN2O, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The evolution from human health-focused risk assessment to landscape-scale analysis represents a critical advancement in our ability to manage complex environmental challenges. Contemporary LER methodologies, which integrate ecosystem services, resilience theory, and spatial simulation, provide a powerful, scientifically-grounded framework for diagnosing ecological health and guiding sustainable land-use planning [2] [7]. The protocols outlined herein offer a standardized yet flexible approach applicable to diverse regions, from urbanizing cities to ecologically fragile watersheds.

Future methodological research should focus on several frontiers:

- Dynamic Process Integration: Moving beyond static pattern indices to incorporate dynamic ecological process models that better reflect feedback loops between pattern, process, and risk [2].

- Multi-Scale Synthesis: Developing frameworks to seamlessly integrate LER assessments across local, regional, and global scales to inform coordinated policy action.

- Big Data and AI Enhancement: Leveraging high-resolution remote sensing, citizen science data, and artificial intelligence (e.g., deep learning for pattern recognition) to improve the accuracy and real-time capability of risk monitoring and prediction [8].

- Enhanced Decision-Support Tools: Translating LER maps and scenarios into interactive platforms for stakeholders and policymakers, directly linking assessment outcomes to land-use zoning and conservation investment decisions [2] [6].

By continuing to refine these tools and protocols, the scientific community can strengthen the foundation for evidence-based ecological governance, ensuring that landscape ecological risk assessment remains a vital instrument in the pursuit of ecosystem sustainability and human well-being.

Introduction Within the interdisciplinary field of landscape ecological risk assessment (LER), methodological rigor is paramount. This article synthesizes two distinct yet conceptually analogous frameworks: the regulatory guidelines of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the physiological Pressure-Receptor-Response (PRR) model. The EPA's framework provides a structured, policy-driven approach to managing anthropogenic environmental stress, while the PRR model offers a mechanistic, systems-level understanding of biological responses to physical forces. Together, they form a complementary foundation for LER methodology, enabling researchers to quantify stressors, characterize receptor sensitivity, and predict systemic responses across spatial and biological scales [9] [10] [11].

1. The EPA Regulatory Framework: Application in Risk Assessment The EPA's guidelines establish a formal process for identifying, evaluating, and controlling environmental risks. A contemporary application is found in the agency's management of methane emissions from the oil and natural gas sector under rules OOOOb and OOOOc [9] [12].

1.1 Core Principles and Recent Regulatory Actions The framework operates on the principles of source identification, technological feasibility, and cost-benefit analysis. In March 2024, the EPA announced New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) and Emissions Guidelines for this sector [9]. A subsequent Interim Final Rule (IFR) in July 2025 extended multiple compliance deadlines, a move finalized in November 2025 [9] [12]. Key extensions include an 18-month delay for requirements on control devices, equipment leaks, and storage vessels, and an additional 180-day extension for continuous monitoring of flares and enclosed combustion devices [9] [12]. The stated rationale is to provide "more realistic timelines" and address industry-identified challenges related to supply chain and personnel limitations [9]. The EPA estimates these extensions will save an estimated $750 million in compliance costs over 11 years [9].

1.2 Quantitative Summary of Key EPA Rule Deadlines Table: Key Compliance Deadlines from EPA's 2025 Final Rule on Oil and Gas Sources (OOOOb/c) [9] [12]

| Requirement Category | Original 2024 Rule Deadline | 2025 Final Rule Extension | New Final Deadline (from IFR publication) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control Devices, Equipment Leaks, Storage Vessels | Specified in 2024 rule | Extended by 18 months | 18 months post-Federal Register publication |

| State Implementation Plans (for existing sources) | Specified in 2024 rule | Extended by 18 months | 18 months post-Federal Register publication |

| "Super Emitter" Program Implementation | Specified in 2024 rule | Extended by 18 months | 18 months post-Federal Register publication |

| Flare/Combustor Continuous Monitoring | November 28, 2025 | Extended by 180 days (from IFR's 120-day extension) | 300 days post-Federal Register publication |

| Annual NSPS OOOOb Reports (initially due before rule) | Prior to effective date | Grace period of 360 days | 360 days from effective date of final action |

2. The Pressure-Receptor-Response (PRR) Model: A Biomechanistic Framework The PRR model describes how mechanical forces (pressure) are transduced by specialized receptors to elicit calibrated physiological responses. This is exemplified by the arterial baroreceptor system, a canonical negative feedback loop for blood pressure homeostasis [11].

2.1 Anatomical and Functional Basis Arterial baroreceptors are mechanosensitive nerve endings located in the carotid sinuses and aortic arch. They are stimulated by stretch of the vessel wall caused by increased arterial pressure [11]. This sensory information is relayed via the glossopharyngeal (carotid) and vagus (aortic) nerves to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the medulla oblongata [11]. The NTS integrates this input and modulates autonomic outflow: increased baroreceptor firing inhibits sympathetic tone and enhances parasympathetic activity, leading to vasodilation, reduced heart rate, and a consequent decrease in blood pressure [11]. The system demonstrates sophisticated features like dual-fiber signaling (rapid A-fibers for dynamic control and slower C-fibers for tonic control) and receptor "resetting" in chronic hypertension [11].

2.2 Experimental Elucidation of PRR Interactions Research has expanded the model to examine interactions between different pressor pathways. A key 2019 study investigated the interplay between Central Command (CC, from higher brain centers) and the Exercise Pressor Reflex (EPR, from muscle afferents) in normotensive (WKY) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats [13]. The protocol involved decerebrated, paralyzed animals. CC was mimicked by electrically stimulating the Mesencephalic Locomotor Region (MLR; 20–50 μA), while the EPR was simulated by stimulating the sciatic nerve (SN; 3, 5, and 10 × motor threshold) [13]. The pressor (blood pressure) responses were measured individually and concurrently. Findings revealed an inhibitory interaction: the summed individual responses were greater than the simultaneous response. This neural "occlusion" was attenuated in SHR rats, suggesting dysfunctional integration of pressor pathways in hypertension [13].

3. Integrated LER Methodology: Synthesizing the Frameworks Landscape ecological risk assessment leverages the logical structures of both frameworks. The EPA model provides the regulatory and source-stress-receptor paradigm, while the PRR model offers a template for quantifying landscape sensitivity and nonlinear responses.

3.1 Conceptual Integration In LER, anthropogenic activities (EPA "sources") exert "pressure" on landscape patches (the "receptors"). The receptor's vulnerability is a function of its structural and functional characteristics, analogous to the density and sensitivity of baroreceptors. The landscape-level "response" is a change in ecosystem services, stability, or pattern, mirroring the integrated cardiovascular outcome [10]. This synthesis allows for modeling complex, cascading effects across spatial scales.

3.2 Application in Landscape Analysis: A Case Study A 2023 study of the Fuchunjiang River Basin, China, demonstrates this integrated approach [10]. Using land use data (1990-2020), researchers calculated a Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI) based on landscape pattern indices like fragmentation, loss, and dominance. Their spatiotemporal analysis found risk was "high in the northwest and low in the southeast," with an overall decreasing trend from 1990 to 2020 [10]. Statistical geodetector analysis identified GDP, human interference, and changes in arable/ residential land areas as dominant influencing factors. Crucially, the coupling between LERI and GDP exhibited an inverted "U" shaped Environmental Kuznets Curve relationship, illustrating a complex systemic response to economic pressure [10].

Table: Key Metrics and Findings from the Fuchunjiang River Basin LER Case Study (1990-2020) [10]

| Metric Category | Specific Indicator/Findings | Interpretation in PRR Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape Pattern Change | Increased agglomeration; decreased loss index. | Altered "receptor" structural configuration. |

| Spatial Risk Distribution | "High in northwest, low in southeast." | Spatial heterogeneity in receptor sensitivity. |

| Temporal Risk Trend | Overall decreasing trend at basin scale. | Systemic adaptation or successful mitigation. |

| Dominant Influencing Factors | GDP, human interference, land use change areas. | Key sources of landscape "pressure." |

| Economy-Risk Relationship | Inverted "U" shaped curve (EKC) with GDP. | Nonlinear, threshold-dependent systemic response. |

4. Detailed Application Notes & Protocols

4.1 Protocol: Simulating Pressor Pathway Interactions (In Vivo) This protocol is adapted from studies investigating central and peripheral pressor mechanism interactions [13].

- Objective: To quantify the interactive pressor response between central command (CC) and the exercise pressor reflex (EPR) in an animal model.

- Subjects: Age-matched male normotensive (e.g., WKY) and hypertensive (e.g., SHR) rats (13-16 weeks) [13].

- Surgical Preparation:

- Anesthetize with isoflurane (4% induction, 1.5-2% maintenance) [13].

- Cannulate carotid artery (for blood pressure monitoring) and jugular vein (for fluid/drug infusion) [13].

- Perform pre-collicular decerebration, discontinue anesthesia, and wait >1.25 hours for stabilization [13].

- Place concentric bipolar electrode in the Mesencephalic Locomotor Region (MLR) for CC simulation [13].

- Isolate and mount the sciatic nerve (SN) on a bipolar electrode for EPR simulation [13].

- Administer neuromuscular blocker (e.g., pancuronium) and initiate artificial ventilation post motor threshold determination [13].

- Stimulation & Data Acquisition:

- Individual Stimulation: Record baseline and pressor response to MLR stimulation (e.g., 20, 30, 40, 50 μA) and SN stimulation (e.g., 3, 5, 10 × MT) separately [13].

- Concurrent Stimulation: Apply a constant intensity SN stimulus while varying MLR intensity, and vice versa [13].

- Continuously record mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), and renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) if measured [13].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the algebraic sum of individual stimulus responses. Compare this sum to the response during concurrent stimulation to identify interactive effects (e.g., occlusion). Compare patterns between animal groups [13].

4.2 Protocol: Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment via Remote Sensing This protocol is based on the landscape pattern-based evaluation method [10].

- Objective: To assess spatiotemporal changes in landscape ecological risk for a defined basin or region.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire multi-temporal land use/land cover (LULC) classification data (e.g., for 1990, 2000, 2010, 2020) from satellite remote sensing (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel) for the study area [10].

- Landscape Pattern Analysis:

- Divide the study area into assessment units (e.g., townships, watershed grids) [10].

- Calculate landscape pattern indices for each unit and time period:

- Fragmentation Index (Ci): Ci = ni / Ai, where ni is patch number and Ai is total area of landscape type i [10].

- Loss Index (Si): Represents the vulnerability of landscape type i (often based on expert judgment or ecological value) [10].

- Dominance Index (Di): Measures the relative importance of landscape type i in the overall pattern [10].

- Risk Index Calculation: Compute the Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI) for each spatial unit k: LERI_k = ∑ (Ei * Ai) / A_k, where Ei is the ecological risk degree of landscape type i (Ei = Ci * Si * Di), Ai is the area of type i in unit k, and A_k is the total area of unit k [10].

- Spatiotemporal & Statistical Analysis:

5. Visualization of Frameworks and Pathways

Diagram 1: EPA Regulatory Framework as a Cyclic Process (Width: 760px)

Diagram 2: Core Baroreceptor Pressure-Receptor-Response Pathway (Width: 760px)

6. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Featured Experiments

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function in Protocol | Key Reference/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflurane | Anesthetic | Induction and maintenance of surgical anesthesia in rodent models. | [13] |

| Concentric Bipolar Electrode | Surgical Tool | Precise electrical stimulation of discrete brain regions (e.g., MLR). | [13] |

| Pancuronium Bromide | Neuromuscular Blocker | Induces paralysis to isolate cardiovascular effects from muscle movement during nerve stimulation. | [13] |

| NaHCO3/Dextrose Ringer Solution | Physiological Fluid | Maintains fluid balance, electrolyte homeostasis, and baseline blood pressure during experiments. | [13] |

| Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Data | Geospatial Data | The foundational dataset for calculating landscape pattern indices and ecological risk. | [10] |

| GIS Software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS) | Analysis Tool | Platform for spatial analysis, grid creation, index calculation, and map generation in LER studies. | [10] |

| Geodetector Software | Statistical Tool | Quantifies the driving forces and interactions behind spatial patterns of landscape ecological risk. | [10] |

The Central Role of Landscape Pattern and Process in Risk Assessment

Application Notes: Integrating Pattern and Process in LER Assessment

Landscape Ecological Risk (LER) assessment has evolved from static, pattern-based analyses to dynamic frameworks that integrate ecological processes and resilience. The core advancement lies in coupling traditional landscape pattern indices with functional metrics of ecosystem services and stability, moving beyond mere spatial heterogeneity to assess the systemic vulnerability and response capacity of socio-ecological systems [2].

Recent methodological optimizations address key limitations of traditional models, notably the strong subjectivity in assigning landscape vulnerability and the disconnect between pattern indices and ecological processes [2]. The contemporary approach reframes vulnerability not by arbitrary land-use rankings but by quantifying the loss of key ecosystem services—such as water retention, soil conservation, and carbon sequestration—which directly reflect functional degradation [2]. Concurrently, the integration of Ecosystem Resilience (ER) into the assessment framework introduces a critical temporal dimension. Resilience characterizes a system's capacity to absorb disturbance and recover its structure and function, thereby modulating the final risk outcome [2]. Spatially, LER and ER exhibit a non-linear, often quadratic relationship, where increasing resilience generally corresponds with decreasing risk, enabling sophisticated zoning for management [2].

Empirical applications across diverse Chinese watersheds and plains demonstrate the scalability of this integrated approach. Studies in the Luo River Watershed, Xin'an River Basin, Jianghan Plain, and Bosten Lake Basin consistently utilize a grid-based sampling framework (e.g., 3 km x 3 km or watershed-based units) to calculate a composite LER index [2] [14] [3]. The spatial correlation of LER is persistently high (Global Moran's I > 0.7), confirming that risk is a clustered, spatially auto-correlated phenomenon rather than a random distribution [15]. Driving force analyses, increasingly conducted via the GeoDetector model, consistently identify land use type and natural factors (elevation, NDVI, temperature) as primary determinants, while socioeconomic factors play a secondary, though significant, role [2] [14] [3].

The ultimate application is risk-informed zoning for ecological management. By coupling LER and ER via bivariate spatial autocorrelation, landscapes can be partitioned into Adaptation, Conservation, and Restoration regions, guiding targeted interventions [2]. Furthermore, coupling LER assessment with multi-scenario simulation models (e.g., Markov-PLUS) allows for the predictive evaluation of future risk under different development pathways, transforming the methodology from a diagnostic to a strategic planning tool [3].

Key Quantitative Findings in LER Research

Table 1: Summary of Key LER Assessment Studies and Quantitative Findings (2000-2025)

| Study Area & Period | Dominant Landscape Change | LER Trend | Primary Driving Factors (Identified via GeoDetector) | Spatial Autocorrelation (Global Moran's I) | Management Zoning Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luo River Watershed (2001-2021) [2] | Urban expansion, cropland change. | Overall increase (0.43 to 0.44); 67.61% of area saw increased risk. | Land use type, Elevation, Climate factors. | Not explicitly stated; used bivariate Moran's I for LER-ER coupling. | Three zones delineated: Ecological Adaptation, Conservation, and Restoration. |

| Xin'an River Basin (1990-2020) [14] | Forest expansion, cropland/tea plantation decline, urban growth. | Overall decline, especially post ecological compensation policy. | Natural factors (Elevation, Temperature). | Distinct clustering patterns reported. | Policy assessment shows ecological compensation reduces LER. |

| Jianghan Plain (2000-2020) [3] | Significant conversion of cropland to built-up land; cropland-water body interchange. | Increased then decreased; dominated by medium-high risk. | NDVI (primary), other natural environmental factors. | Analysis performed; pattern "high in southeast, low in central/north". | Multi-scenario simulation for 2030 predicts lower risk under ecological/cropland protection vs. natural/economic development. |

| Bosten Lake Basin (2000-2020) [15] | Dominated by grassland and bare area dynamics. | Area of high-risk zones increased; lower/lowest risk zones shrank (62.02% to 58.44%). | Not analyzed in detail. | Exceeded 0.7 for all three periods, indicating strong positive spatial autocorrelation. | Foundation for multi-scale risk studies in fragile ecoregions. |

Table 2: Core Components of an Optimized LER Assessment Model [2] [3]

| Component | Description | Calculation/Metric | Rationale & Advancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Disturbance Index (LDI) | Measures intensity of external stress on a landscape. | Composite of fragmentation (C), isolation (S), and dominance (D) indices: a*C + b*S + c*D (a, b, c are weights). |

Quantifies structural pressure from human activity and natural change. |

| Landscape Vulnerability Index (LVI) | Assesses a landscape type's inherent sensitivity to disturbance. | Traditional: Expert-assigned ordinal ranks (1-6) by land use type. Optimized: Quantified via inverse of composite ecosystem service value (e.g., water retention, soil conservation) [2]. | Replaces subjective ranking with objective, process-based functional metrics. |

| Landscape Loss Index (LLI) | Integrated measure of potential ecological loss. | LLI = LDI * LVI. |

Combines external pressure with internal susceptibility. |

| Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI) | Final risk value for an assessment unit (grid). | LER_k = ∑ (A_ki / A_k) * LLI_ki where A_ki is area of landscape i in unit k [3]. |

Weighted average of loss, representing cumulative risk per spatial unit. |

| Ecosystem Resilience (ER) | Capacity to resist disturbance and recover function. | Composite index of vegetation vigor, soil moisture, landscape connectivity, etc. [2]. | Introduces adaptive capacity, modulating final risk and enabling dynamic management zoning. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Grid-Based LER Assessment with Integrated Vulnerability

Objective: To quantitatively assess spatiotemporal LER by integrating ecosystem service-based vulnerability and landscape pattern disturbance. Workflow: See Diagram 1: LER Assessment Workflow. Materials: Land use/cover (LULC) raster data (e.g., 30m resolution), Digital Elevation Model (DEM), soil type data, precipitation data, NDVI time series, GIS software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS), Fragstats software, statistical software (R, Python). Procedure:

- Data Preparation & Scale Determination: Preprocess all spatial data to a unified coordinate system and resolution. Determine the optimal assessment grain and extent using semi-variance analysis or by setting the grid size to 2-5 times the average patch area of the landscape [15]. Create a vector grid (e.g., 3km x 3km) over the study area [3].

- Landscape Metrics Calculation: Use Fragstats to calculate landscape pattern indices (Patch Density, Edge Density, Splitting Index, Aggregation Index) for each LULC class within each grid cell for each time period.

- Compute Landscape Disturbance Index (LDI): For each LULC class i, standardize the selected fragmentation, isolation, and dominance indices and combine them using a weighted sum (e.g., 0.5, 0.3, 0.2) to generate a class-specific LDI [3].

- Quantify Landscape Vulnerability Index (LVI):

- Ecosystem Service Assessment: Model key services (e.g., water yield, sediment retention, carbon storage) using tools like InVEST or the RUSLE equation. Generate a composite ecosystem service (ES) value map.

- Assign LVI: For each LULC class, calculate the mean composite ES value. Normalize these mean values (0-1). Define LVI for each class as

LVI_i = 1 - Normalized_ES_i. This ensures low-service (highly vulnerable) landscapes receive higher LVI scores [2].

- Calculate Landscape Loss & Risk Index: Compute

LLI_i = LDI_i * LVI_ifor each LULC class. For each grid cell k, calculate the area-weighted LER:LER_k = ∑ (Area_ki / Area_k) * LLI_i. Map the results and classify risk levels (e.g., Low, Medium-Low, Medium, Medium-High, High) using natural breaks. - Spatio-temporal Analysis: Analyze change between periods. Perform spatial autocorrelation analysis (Global & Local Moran's I) to identify risk clusters and outliers [15].

Protocol B: Coupled LER-ER Analysis for Ecological Management Zoning

Objective: To integrate Ecosystem Resilience (ER) with LER for identifying spatially targeted management zones. Workflow: See Diagram 2: LER-ER Coupling for Management Zoning. Materials: LER results from Protocol A, remote sensing indices (NDVI, LSWI for soil moisture, etc.), landscape connectivity metrics, GIS software with spatial statistics toolbox. Procedure:

- Ecosystem Resilience (ER) Quantification: Construct a multi-factor ER index. Common indicators include:

- Vegetation Vigor: Mean annual NDVI.

- Soil/Moisture Status: Land Surface Water Index (LSWI) or soil organic carbon.

- Landscape Connectivity: Probability of connectivity index based on core habitat patches.

- Diversity: Shannon's Diversity Index of LULC. Standardize and weight these factors (e.g., using Principal Component Analysis) to create a composite ER raster, resampled to the LER grid.

- Bivariate Spatial Coupling: Perform a bivariate Local Moran's I analysis between LER and ER grids. This identifies five types of spatial relationships: High-LER & Low-ER (High-High), Low-LER & High-ER (Low-Low), High-LER & High-ER (High-Low), Low-LER & Low-ER (Low-High), and non-significant.

- Management Zoning: Interpret the bivariate clusters as management zones [2]:

- Ecological Restoration Zone (High-LER, Low-ER): Highest priority for active intervention to reduce pressure and restore functionality.

- Ecological Adaptation Zone (High-LER, High-ER): Manage stress while monitoring resilient systems' natural adjustment.

- Ecological Conservation Zone (Low-LER, High-ER): Protect and maintain current healthy, resilient state.

- Monitoring Zone (Low-LER, Low-ER): Areas with low risk but low capacity; prevent degradation.

- Driving Force Analysis: Use the Geodetector model (

gdpackage in R) to quantify the determinant power (q-statistic) of natural and socioeconomic factors (e.g., elevation, slope, GDP, population density) on both LER and ER spatial patterns. The interaction detector can reveal synergistic driving forces [3].

Protocol C: Multi-Scenario LER Simulation and Prediction

Objective: To project future LER under different land use and policy scenarios. Materials: Historical LULC maps (multiple periods), spatial driver variables (distance to roads, cities, slope, etc.), future scenario storylines, simulation software (e.g., PLUS model, FLUS model). Procedure:

- Land Use Change Simulation:

- Scenario Definition: Develop 3-4 scenario storylines (e.g., Natural Development, Economic Priority, Ecological Protection, Cropland Protection) [3].

- Model Calibration: Use the Markov-PLUS model. A Markov chain predicts total demand per LULC class. The PLUS model uses a Land Expansion Analysis Strategy (LEAS) to mine the drivers of past transitions and a Cellular Automata (CA) based on Multi-class Random Patch Seeds to allocate future changes spatially under different scenario constraints.

- Simulation & Validation: Simulate land use for a target year (e.g., 2030). Validate the model by simulating a known year and comparing with actual data using Kappa coefficient and FoM.

- Future LER Assessment: Apply the LER assessment model (Protocol A) to the simulated future LULC maps.

- Comparative Risk Analysis: Compare the area, distribution, and spatial statistics of risk levels across different future scenarios to inform policy planning and land use optimization [3].

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents, Datasets, and Software for LER Research

| Item Name | Type | Specification/Example Source | Primary Function in LER Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-temporal Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Data | Core Dataset | 30m Global Land Cover datasets (e.g., FROM-GLC, GlobeLand30), or national land use surveys. | Serves as the fundamental spatial data layer for calculating landscape pattern indices and tracking change. |

| Google Earth Engine (GEE) | Cloud Platform | Platform with petabytes of satellite imagery (Landsat, Sentinel) and geospatial datasets [14]. | Enables efficient large-scale LULC classification, time-series analysis (NDVI), and ecosystem service modeling without local computational burdens. |

| Fragstats Software | Analytical Tool | Latest version (e.g., Fragstats 4.2). | The standard software for calculating a comprehensive suite of landscape pattern metrics (patch, class, and landscape level) from LULC rasters. |

| InVEST Model Suite | Ecosystem Service Model | Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs by Natural Capital Project. | Provides spatially explicit models for quantifying key ecosystem services (water yield, sediment retention, carbon storage) used to derive objective Landscape Vulnerability Indices [2]. |

| Geodetector Software/Package | Statistical Tool | gd package in R, or standalone GeoDetector software. |

Quantifies the driving forces behind LER spatial heterogeneity, assessing factor contributions (q-statistic) and interaction effects [14] [3]. |

| PLUS (Patch-generating Land Use Simulation) Model | Simulation Software | Coupled with Markov chain for demand projection. | Simulates future land use changes under different scenarios with high spatial accuracy, enabling predictive LER assessment [3]. |

| Sentinel-2/Landsat 8-9 Imagery | Remote Sensing Data | Multispectral satellite data (10-30m resolution). | Source for calculating vegetation indices (NDVI for resilience), classifying LULC, and monitoring environmental variables. |

| SRTM or ASTER GDEM | Topographic Data | 30m resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM). | Provides essential terrain variables (elevation, slope) as drivers for both ecosystem services and LER patterns. |

| Iroxanadine hydrochloride | Iroxanadine hydrochloride, CAS:276690-59-6, MF:C14H21ClN4O, MW:296.79 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Quercetin 3,5,3'-trimethyl ether | Quercetin 3,5,3'-trimethyl ether, MF:C18H16O7, MW:344.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Landscape ecological risk (LER) assessment represents a critical advancement in ecological risk evaluation by shifting focus from single-element receptors to the ecosystem as a whole, with particular emphasis on spatiotemporal differentiation and scale effects [16]. Traditional ecological risk assessment often overlooks the spatial heterogeneity inherent in landscapes—the uneven distribution of ecosystems, land uses, and human disturbances across geographical space. This heterogeneity fundamentally influences how ecological processes operate and how risks propagate through systems.

The unique perspective of LER methodology lies in its capacity to translate complex landscape patterns into measurable risk indicators. Unlike conventional approaches that might assess chemical contaminants or single-species impacts, LER evaluates how landscape pattern changes—particularly fragmentation, connectivity loss, and land use conversion—affect ecosystem stability, function, and resilience [7]. This approach is especially relevant in regions experiencing rapid urbanization, where human activities drastically reconfigure land resources and create new ecological pressures [16].

This application note details protocols for assessing LER with explicit consideration of spatial heterogeneity, providing researchers with methodological frameworks for quantifying and interpreting risk patterns across varied landscapes.

Core Conceptual Framework: From Landscape Pattern to Ecological Risk

The foundational principle of LER assessment is that landscape structure influences ecological function and process. The "patch-corridor-matrix" model provides the basic language for describing this structure [7]. Risk emerges from the interaction between the spatial configuration of landscape elements (patches of different land use types) and the ecological vulnerabilities associated with those elements.

Spatial heterogeneity matters in this framework for several key reasons:

- Risk Propagation: Heterogeneous landscapes can either impede or facilitate the spread of disturbances (e.g., pollution, fires, invasive species).

- Habitat Quality: The size, shape, and connectivity of habitat patches directly determine species viability and biodiversity.

- Ecosystem Services: The spatial arrangement of forests, wetlands, agricultural land, and urban areas affects water regulation, soil retention, and climate moderation services.

- Cumulative Impacts: Multiple, spatially dispersed stressors can have synergistic effects that are only apparent when viewed at a landscape scale.

The following conceptual diagram illustrates the analytical workflow for assessing LER, highlighting how spatial heterogeneity is quantified and integrated into risk indices.

Figure 1: LER Assessment Workflow Integrating Spatial Analysis. This workflow demonstrates the sequential steps from data acquisition to risk visualization, with an explicit feedback loop for analyzing spatiotemporal dynamics [16] [7].

Quantitative LER Assessment: Models, Indices, and Spatial Metrics

A robust LER assessment quantifies both the intensity of ecological disturbance and its spatial distribution. The following tables summarize core quantitative models, indices, and representative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Core Landscape Pattern Indices for LER Assessment [16] [7]

| Index Category | Specific Index | Formula / Description | Ecological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation | Patch Density (PD) | PD = N / A (N=number of patches, A=total area) |

Higher PD indicates greater fragmentation, often linked to habitat degradation and disrupted flows. |

| Diversity | Shannon's Diversity Index (SHDI) | SHDI = -∑(Pᵢ * lnPᵢ) (Pᵢ=proportion of class i) |

Higher SHDI suggests greater landscape diversity and potential stability, but can indicate anthropogenic disturbance in certain contexts. |

| Aggregation | Aggregation Index (AI) | Percentage of like adjacencies among a patch type. | Lower AI suggests a more dispersed or fragmented pattern of a given land use type, potentially increasing edge effects. |

| Shape Complexity | Landscape Shape Index (LSI) | LSI = E / (2 * sqrt(Ï€ * A)) (E=total edge length) |

LSI ≥ 1. Higher values indicate more complex, irregular patch shapes, influencing species interactions and microclimates. |

| Connectivity | Connectance Index (CONNECT) | CONNECT = (∑Cᵢⱼ) / N (C=connectivity of patches) |

Measures functional connectivity between patches; critical for assessing habitat network resilience. |

Table 2: Representative LER Values and Trends from Case Studies

| Study Area & Period | Key Land Use Change Trend | Overall LER Trend & Value Range | Identified Spatial Pattern | Primary Driving Forces (via Geodetector) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities along Lower Yellow River (2000-2020) [16] | Decrease in cropland; increase in impervious surface. | Fluctuating, slight downward trend (0.1761 to 0.1751). | Center of gravity moving towards river mouth; increasing dispersion. | Natural factors > Social factors. Interaction of any two factors > single factor effect. |

| Harbin, China (2000-2020) [7] | Cultivated land and woodland dominant; development land increased; unused area decreased. | Overall downward trend, primarily medium-risk. | "High in west and north, low in east and south"; high-risk clusters around water bodies. | DEM had greatest explanatory power; interaction of DEM & annual precipitation was dominant. |

| General LER Risk Levels | N/A | Low Risk: < 0.15Medium Risk: 0.15–0.20High Risk: > 0.20 [16] | High spatial autocorrelation is common (Moran's I > 0.7) [7]. | Topography (DEM), climate (precipitation), and human activity (GDP, road density) are ubiquitous drivers. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: LER Index Calculation Based on Landscape Units

This protocol outlines the standard method for calculating a comprehensive LER index by integrating landscape disturbance and ecosystem vulnerability.

1. Objective: To compute a spatially explicit Landscape Ecological Risk Index that captures the combined effect of landscape pattern disturbance and the intrinsic sensitivity of different ecosystem types.

2. Materials & Input Data:

- Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Data: Multi-temporal raster datasets (e.g., 30m resolution) classified into types such as forest, grassland, cropland, water, barren land, and impervious surface [16].

- GIS Software: ArcGIS, QGIS, or FRAGSTATS for spatial analysis and index calculation.

- Sampling Grid: A vector grid (e.g., 2km x 2km or 5km x 5km) overlaid on the study area to serve as the basic assessment unit.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1 - Landscape Classification and Grid Division: Reclassify LULC data into consensus categories. Overlay a uniform sampling grid over the study area.

- Step 2 - Calculate Landscape Pattern Indices per Grid Cell: For each grid cell, calculate a suite of indices (see Table 1). A critical composite metric is the Landscape Disturbance Index (LDI).

LDI = a*Ci + b*Si + c*Di- Where

Ciis the fragmentation index,Siis the separation index, andDiis the dominance index for gridi. Weightsa, b, csum to 1 and are often determined via expert judgment or principal component analysis.

- Step 3 - Assign Ecosystem Vulnerability Weights: Assign a relative vulnerability weight (

Fk) to each LULC typek(e.g., Water: 0.8; Forest: 0.6; Cropland: 0.4; Impervious: 0.2) based on its sensitivity to disturbance and ecological function. - Step 4 - Compute LER Index per Grid Cell:

LERi = LDIi * ∑(Aki * Fk) / Ai- Where

LERiis the risk index for gridi,Akiis the area of landscape typekin gridi, andAiis the total area of gridi. This formula integrates spatial disturbance with the vulnerability of the landscape composition.

- Step 5 - Spatial Interpolation and Classification: Use Kriging or Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) interpolation on all grid cell

LERivalues to create a continuous risk surface. Reclassify the surface into distinct risk levels (e.g., Low, Medium-Low, Medium, Medium-High, High).

4. Output: A geospatial map of Landscape Ecological Risk and an attribute table containing the LER value for each spatial unit.

Protocol 2: Analyzing Driving Forces of Spatial Heterogeneity with Geodetector

This protocol uses the Geodetector method to quantitatively assess the drivers behind the observed spatial patterns of LER.

1. Objective: To identify and quantify the influence of natural and socioeconomic factors on the spatial heterogeneity of LER, including single-factor effects and interaction effects.

2. Materials & Input Data:

- Dependent Variable: Raster map of computed LER values.

- Explanatory Variables: Raster layers of candidate driving factors (e.g., DEM, slope, precipitation, temperature, population density, GDP density, distance to roads/waterways, land use degree) [16] [7].

- Software: R with

GDpackage, or dedicated Geodetector software.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1 - Data Layer Preparation and Discretization: Ensure all factor layers are aligned (same extent, resolution). Discretize continuous factor data (e.g., DEM, GDP) into strata using appropriate classification methods (natural breaks, quantiles, etc.). The Optimal Parameters-based Geographical Detector (OPGD) model can optimize this step [16].

- Step 2 - Factor Detector Analysis: Run the Factor Detector to measure the explanatory power (

qstatistic) of each single factor on the spatial distribution of LER.q = 1 - (∑ Nh * σh²) / (N * σ²)- Where

h=1..Lis the stratum of the factor;NhandNare stratum and population sample sizes;σh²andσ²are variances. Theqvalue ranges [0,1]; a largerqindicates a stronger determining power of the factor.

- Step 3 - Interaction Detector Analysis: Run the Interaction Detector to assess how the combined influence of two factors affects LER. Evaluate whether the interaction is: Non-linear Weakened, Single-factor Weakened, Bi-enhanced, Independent, or Non-linear Enhanced.

- Step 4 - Risk Detector Analysis: Use the Risk Detector (e.g., t-test) to determine if there is a significant difference in the mean LER value between two strata of a factor.

- Step 5 - Ecological Detector Analysis: Use the Ecological Detector (e.g., F-test) to determine if there is a significant difference in the influence of two different factors on LER.

4. Output: Quantitative q values for all factors, interaction q values for factor pairs, and statistical significance tests identifying the dominant drivers and their interactions shaping LER spatial heterogeneity.

The interplay between landscape patterns, ecological processes, and external drivers is visualized in the following conceptual diagram, which underpins the analytic protocols.

Figure 2: Conceptual Framework of Spatial Heterogeneity in LER. This diagram shows how natural and human driving forces shape landscape structure, which in turn governs ecological processes to jointly determine LER. The system features constant feedback loops [16] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools and Platforms for LER Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Primary Function in LER Research | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Pattern Analysis | FRAGSTATS | The industry-standard software for calculating a comprehensive suite of landscape pattern metrics from raster maps. | Essential for Protocol 1 (Step 2). Input requires a classified LULC raster. Batch processing enables multi-temporal analysis. |

| Geospatial Analysis & Modeling | ArcGIS Pro / QGIS | Core platform for data management, LULC reclassification, grid creation, spatial interpolation, and map visualization. | Used throughout all protocols. The Raster Calculator and Zonal Statistics tools are particularly important for index computation. |

| Spatial Statistical Analysis | R (with spdep, GD packages) |

Statistical computing for spatial autocorrelation (Global/Local Moran's I) and Geodetector analysis. | GD package implements the Geodetector model for Protocol 2. Critical for quantifying driving forces and spatial clustering. |

| Land Use Change Simulation | PLUS (Patch-generating Land Use Simulation) Model | A CA-based model that simulates future land use scenarios by leveraging a land expansion analysis strategy and random forest algorithm [7]. | Used for forecasting future LER under different development scenarios (e.g., natural growth, ecological protection). |

| Automated Accessibility Checking | Color Contrast Analysers (e.g., CCA, WAVE) | Tools to verify that graphical outputs (charts, maps) meet minimum color contrast ratios (≥ 3:1 for large graphics) for accessibility [17] [18]. | Critical for ensuring research findings are communicated inclusively. Should be applied to all final presentation maps and figures. |

| NMDA receptor antagonist-3 | NMDA receptor antagonist-3, MF:C13H19N3O6, MW:313.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| tert-Butyl 2-((5-bromopentyl)oxy)acetate | tert-Butyl 2-((5-bromopentyl)oxy)acetate, MF:C11H21BrO3, MW:281.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The explicit incorporation of spatial heterogeneity elevates LER assessment from a descriptive exercise to an analytical framework capable of diagnosing the structural causes of ecological risk. Methodologies that integrate landscape pattern indices with spatial statistical tools like Geodetector allow researchers to move beyond mapping risk to explaining its drivers [16] [7].

Future methodological advancements are likely to focus on:

- Higher Resolution Temporal Analysis: Leveraging annual or seasonal LULC data to understand shorter-term risk dynamics and tipping points.

- Integration with Ecosystem Service Models: Directly linking LER indices to the provision and flow of key ecosystem services (e.g., carbon sequestration, water purification).

- Machine Learning Enhanced Forecasting: Using AI to improve the accuracy of land use change and risk simulation models under complex, non-linear future scenarios.

- Standardization of Vulnerability Weights: Developing region- and ecosystem-specific vulnerability weight (

Fk) databases to improve the comparability of LER studies across different geographies.

By adopting the detailed protocols and tools outlined in this application note, researchers can systematically assess landscape ecological risk, providing a scientifically robust basis for land use planning, ecological conservation, and sustainable development policy.

The LER Assessment Toolkit: Methods, Models, and Practical Applications

Landscape Ecological Risk (LER) assessment is a critical subfield of regional ecological risk analysis that emphasizes spatiotemporal heterogeneity and the effects of scale [7]. It evaluates the potential damage to ecosystem structure, function, and stability resulting from natural or human-induced disturbances within a landscape [7]. The Landscape Ecological Risk Index (LERI) serves as a synthesized, core metric within this assessment framework. It diverges from traditional pollutant-focused ecological risk models by adopting a landscape pattern-centric approach [16]. This methodology treats the landscape mosaic itself as the risk receptor, integrating the cumulative ecological impacts arising from multiple stress sources through changes in landscape pattern [7].

The construction of LERI is grounded in the "pattern-process-risk" paradigm. It operates on the premise that external disturbances (e.g., urbanization, climate change) alter the composition and configuration of land use/cover. These alterations in landscape pattern, measurable through indices, subsequently affect the flow of ecological processes and the stability of ecosystems, manifesting as ecological risk [19]. Within the context of a broader thesis on LER methodology, the LERI provides a quantifiable, spatially explicit foundation for diagnosing risk hotspots, deciphering driving mechanisms, and simulating future risk scenarios under different land-use policies [7].

Core Methodology: Constructing the LERI

The standard LERI construction protocol involves a multi-step process that transforms land use/cover data into a normalized risk surface. The following workflow details this procedure.

Figure 1: LERI Construction and Analysis Workflow [7] [16].

Mathematical Formulation

The LERI for a given spatial unit i (typically a grid cell) is calculated as a composite of key landscape pattern indices [7] [16]:

LERi = Ci × Di × Si

Where:

- Ci (Landscape Fragmentation Index) represents the degree of fragmentation within the cell. It is often derived from the Landscape Division Index or a function of patch density and edge density. Higher fragmentation implies greater disruption to ecological flows.

- Di (Landscape Dominance Index) quantifies the extent to which the landscape is dominated by one or a few patch types. It is calculated from the Landscape Dominance metric based on relative patch area. High dominance can indicate reduced biodiversity and resilience.

- Si (Landscape Isolation Index) measures the degree of isolation of similar patch types. It can be derived from the Euclidean Nearest-Neighbor Distance metric. Greater isolation hinders species movement and gene flow.

Each component index (Ci, Di, Si) is normalized to a 0-1 scale before multiplication to ensure comparability. The resulting LERi value is a unitless, relative measure where a higher value indicates higher ecological risk within that spatial unit [16].

Key Calculation Steps

- Data Preparation: Acquire multi-temporal land use/cover (LULC) raster data (e.g., 30m resolution) for the study area [16].

- Grid Creation: Overlay a vector grid (e.g., 3km x 3km) onto the study region. The grid cell size should be 2-5 times the average landscape patch size to capture pattern dynamics effectively.

- Metric Calculation: For each grid cell and time period, calculate the three core landscape metrics (Ci, Di, Si) using spatial analysis software (e.g., FRAGSTATS).

- LERI Computation: Apply the formula LERi = Ci × Di × Si for each cell.

- Classification: Reclassify the continuous LERI values into distinct risk levels (e.g., Low, Medium-Low, Medium, Medium-High, High) using a classification scheme like Natural Breaks (Jenks).

- Spatial & Temporal Analysis: Analyze the resulting LERI surface for spatial autocorrelation (e.g., using Global and Local Moran's I) and track changes over time [7].

Application Notes: Insights from Contemporary Research

Recent advancements in LERI application emphasize multi-scale analysis and future scenario simulation. The integration of spatial statistical tools like GeoDetector has refined the understanding of driving forces [19] [16].

Table 1: LERI Trends and Drivers from Recent Case Studies (2020-2025)

| Study Area & Reference | Key LERI Trend (Temporal) | Spatial Pattern | Primary Driving Forces Identified | Key Analytical Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities along Lower Yellow River, China [16] | Fluctuating, slight downward trend (0.1761 to 0.1751 from 2000-2020). | Center of gravity moved towards river mouth; increasing dispersion. | Natural factors > Social factors. Interaction of any two factors > single factor effect. | OPGD (Optimal Parameters-based Geodetector) |

| Harbin, China [7] | Overall downward trend (2000-2020), primarily medium risk. | "High in west/north, low in east/south"; highest risk around water bodies. | DEM was strongest natural driver. Interaction of DEM & Annual Precipitation was dominant. | GeoDetector; PLUS model for future scenarios. |

| Three Plateau Lakes Basin, Yunnan, China [19] | Risk reduced overall from global perspective. | Deteriorated areas progressed SW to NE (2000-2020). | Global: Anthropogenic disturbances. Local: Varies by area type (deteriorated vs. improved). | Multi-scale Geodetector analysis. |

| 10-oxo-12(Z),15(Z)-Octadecadienoic Acid | 10-oxo-12(Z),15(Z)-Octadecadienoic Acid, MF:C18H30O3, MW:294.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Amino-PEG4-bis-PEG3-methyltetrazine | Amino-PEG4-bis-PEG3-methyltetrazine, MF:C58H90N14O17, MW:1255.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Multi-Scale Driver Analysis

A seminal 2025 study in the Three Plateau Lakes Basin demonstrated that driving factors operate differently across scales [19]. While a global analysis found anthropogenic disturbances to be most influential, a local-scale analysis of "deteriorated," "improved," and "stable" risk areas revealed nuanced drivers:

- Deteriorated Areas: Intense anthropogenic pressure was the primary driver.

- Improved/Stable Areas: Natural disturbances held greater explanatory power [19]. This underscores the necessity of a multi-scale perspective in LER driver identification to formulate comprehensive and feasible ecological protection strategies [19].

Future Risk Projection

Research in Harbin utilized the PLUS model to simulate land use in 2030 under three scenarios: Business-As-Usual (BAU), Economic Priority (EP), and Ecological Priority (ECP) [7]. The LERI was projected under each scenario:

- The Ecological Priority (ECP) scenario resulted in a slower decrease of ecological land and was identified as the most effective approach for improving landscape ecological conditions [7].

- This application provides a critical decision-support tool, allowing policymakers to visualize the potential long-term ecological consequences of different development pathways.

Experimental Protocols for LERI Research

Protocol A: Comprehensive LERI Assessment and Driver Analysis

Objective: To assess the spatiotemporal evolution of landscape ecological risk and quantify the influence of natural and anthropogenic driving factors.

Materials & Data:

- LULC Data: Multi-temporal (e.g., 2000, 2010, 2020) raster datasets.

- Driving Factor Data: Raster layers for natural (DEM, slope, precipitation, temperature) and anthropogenic (population density, GDP, distance to roads/waterways) variables.

- Software: ArcGIS/QGIS, FRAGSTATS, R/Python with GeoDetector package.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Reclassify LULC data into consistent categories. Project all raster data to a unified coordinate system and resolution.

- LERI Calculation: Follow steps outlined in Section 2.2 to generate LERI raster layers for each time point.

- Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis: Calculate Global Moran's I to determine if LERI exhibits clustering. Perform Local Moran's I analysis to identify specific "High-High" and "Low-Low" clusters [7].

- Driver Detection with GeoDetector:

a. Discretization: Convert continuous driving factor rasters into categorical layers using an optimal method (e.g., natural breaks).

b. Factor Detector: Execute the

factor_detectorfunction to calculate the q-statistic for each factor. The q-value (0-1) indicates the factor's explanatory power on LERI spatial heterogeneity [16]. c. Interaction Detector: Execute theinteraction_detectorfunction to assess whether two factors, when combined, weaken or enhance each other's influence on LERI. Results typically show non-linear or bi-factor enhancement [16]. d. Optimal Parameters: For enhanced accuracy, employ the OPGD model to automatically determine the optimal discretization method and break number for each factor [16].

Protocol B: LERI Projection Using Multi-Scenario Land Use Simulation

Objective: To project future LERI under different socio-economic and policy scenarios.

Materials & Data: Same as Protocol A, plus historical socio-economic data for scenario parameterization.

Procedure:

- Land Use Change Simulation with PLUS Model: a. Use LULC data from two historical periods to extract land expansion and generate development probability maps for each land type via a Random Forest algorithm. b. Define scenario-specific parameters for 2030 (e.g., restricting urban expansion in ECP scenario, promoting cropland protection in EP scenario). c. Run the multi-type random patch seeding mechanism in the PLUS model to generate simulated LULC maps for 2030 under BAU, EP, and ECP scenarios [7].

- Future LERI Assessment: Calculate the LERI for each simulated 2030 LULC map using the standard method.

- Comparative Analysis: Quantify and map the differences in LERI magnitude and spatial distribution among the three future scenarios. Identify areas of greatest risk change under each development pathway.

Visualizing Pathways and Drivers

Understanding the interaction between drivers and LERI requires visualizing complex, non-linear relationships. The following diagram synthesizes the key pathways identified through GeoDetector analysis.

Figure 2: Pathways and Key Drivers in LERI Formation [19] [7] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Software and Analytical Tools for LERI Research

| Tool / "Reagent" | Primary Function in LERI Research | Example Use Case / Note |